User login

Hearing Patient Stories: Use of Medical Humanities on a Large-Scale, Virtual Platform to Improve Clinician Engagement

Hearing Patient Stories: Use of Medical Humanities on a Large-Scale, Virtual Platform to Improve Clinician Engagement

The COVID-19 pandemic presented stressors for patients and health care professionals alike, and the prevalence of health care practitioner burnout and dissatisfaction has risen dramatically.1,2 This, in combination with an increasingly virtual interface between patients and care teams, has the potential to lead to increased depersonalization, anxiety, distress, and diminished overall well-being among clinicians.1,3 Within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), women’s health primary care practitioners (PCPs) are specially trained clinicians thatprovide comprehensive care to women veterans. Data suggest that women’s health PCPs may experience higher rates of burnout and attrition (14% per year) compared to general PCPs in VHA.4 Burnout among PCPs, especially those working at VHA, is well known and likely related to poor interdisciplinary team structure, limited administrative time, high patient complexity, and isolation from additional resources (eg, rural settings).4-7 Increased clinician burnout is associated with poorer quality of care and worsening quality of the doctor-patient relationship.8

The medical humanities can act as a countermeasure to clinician burnout.9,10 Studies have demonstrated that physicians who participate in the medical humanities are more empathic and experience less burnout.11,12 Engaging with patient stories through listening and writing has been a source of fulfillment for clinicians.13 Despite the benefits of narrative medicine, programs are often limited in scope in small face-to-face group settings during elective time or outside work hours.14 The COVID-19 pandemic presented significant challenges to implementing such programming. The VHA is a large health care system with many rural locations, which further limits the availability of traditional small-group and face-to-face trainings. Few studies describe large-scale medical humanities training in virtual learning environments.

NARRATIVE MEDICINE EVENT

To improve satisfaction and engagement among PCPs who care for women veterans, we developed, implemented, and evaluated a large-scale, virtual, interprofessional narrative medicine event aimed at achieving the following: (1) gain a deeper appreciation of the impact of deployments on women veterans; (2) describe the social and emotional challenges faced by women veterans returning from deployment (reintegration); (3) identify strategies to support veterans during reintegration; (4) apply narrative medicine techniques on a large-scale, virtual platform; and (5) assess clinician engagement and satisfaction following participation. We hypothesized that clinician satisfaction and appreciation would improve with a better understanding of the unique complexities of deployment and reintegration faced by women veterans. Utilizing a novel, humanities-based intervention would lead to strong engagement and interaction from participants.

Setting

A 3-hour virtual session was conducted on November 15, 2022, for an interdisciplinary audience. This included physicians and trainees in medicine and behavioral health, nurse practitioners, social workers, dieticians, nurses, and clinical support staff. The training was advertised via emails through established mailing lists and newsletters, reaching a large interdisciplinary VHA audience 90 days prior to the event. This allowed potential participants to dedicate time to attend the session. The training was open to all VHA employees, with no inclusion or exclusion criteria for either the training or the evaluation. The training was delivered within existing space utilized for continuing medical education in women’s health.

For the session, the 93-minute documentary Journey to Normal (jtninc.org) was chosen because it focused on the impact of deployment on women veterans and their experiences when returning home. The film follows the stories of several women veterans through combat and reintegration. The screening was split into 2 segments given the emotional impact and length of the documentary.

A facilitator opened the session by reading a series of reflective prompts centered on women veteran deployment, reintegration, and the stressors surrounding these transitions. The initial prompt served to familiarize participants with the session’s interactive components. Additional prompts were interspersed and discussed in real time and were chosen to mirror the major themes of the documentary: the emotional and psychological impact of deployment and reintegration for women veterans. Short responses and word cloud generation were used and debriefed synchronously to encourage ongoing engagement. Participants responded to prompts through anonymous polling and the chat function of the virtual platform.

During intermission, we introduced My Life, My Story (MLMS). MLMS is a VHA initiative started in 2013 that, with the veteran’s permission, shares a piece of a veteran’s life story with their health care practitioner in their medical chart.15 Evaluation of MLMS has demonstrated positive impacts on assessments of patient-clinician connection.16 The MLMS goal to improve patient-centered care competencies by learning stories of veterans aligned with the overarching goals of this program. Following the film, participants were given 10 minutes to respond to a final reflective prompt. The session ended with a review of existing VHA resources to support returning veterans, followed by a question-and-answer session conducted via chat.

We used the Brightcove virtual platform to stream this program, which facilitated significant interaction between participants and facilitators, as well as between participants themselves. In addition to posing questions to the session leaders, participants could directly respond to each other’s comments within the chat function and also upvote/downvote or emphasize others’ comments.

Evaluation

The evaluation schema was 2-fold. Because this session was presented as a part of the national VA Women’s Health webinar series, a standard evaluation was dictated by the VHA Employee Education System. This survey was electronically disseminated and included questions on occupational category and overall satisfaction, plus 9 standard evaluation questions and 4 program-specific questions tied to the workshop objectives. The standard evaluation questions assessed participant satisfaction with the training, satisfaction with the training environment, and appropriateness of the content. The programspecific questions asked the participants whether the session met the stated learning objectives. All questions used a 5-point Likert scale (1, strongly disagree; 5, strongly agree). Descriptive statistics were used for analysis. Individual chat messages and spontaneous replies were analyzed as a surrogate measures of audience engagement. A qualitative analysis of participants’ final reflections to assess for attitudes related to patient care, empathy, and burnout following participation in this curriculum is forthcoming.

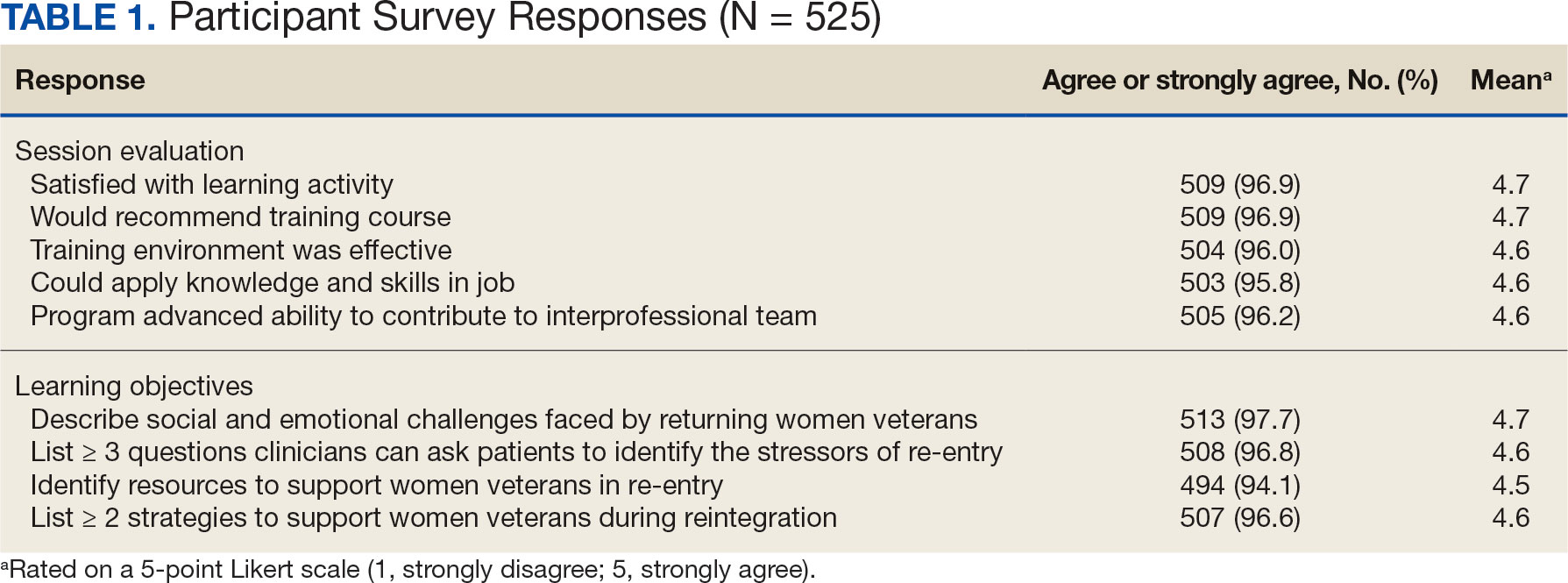

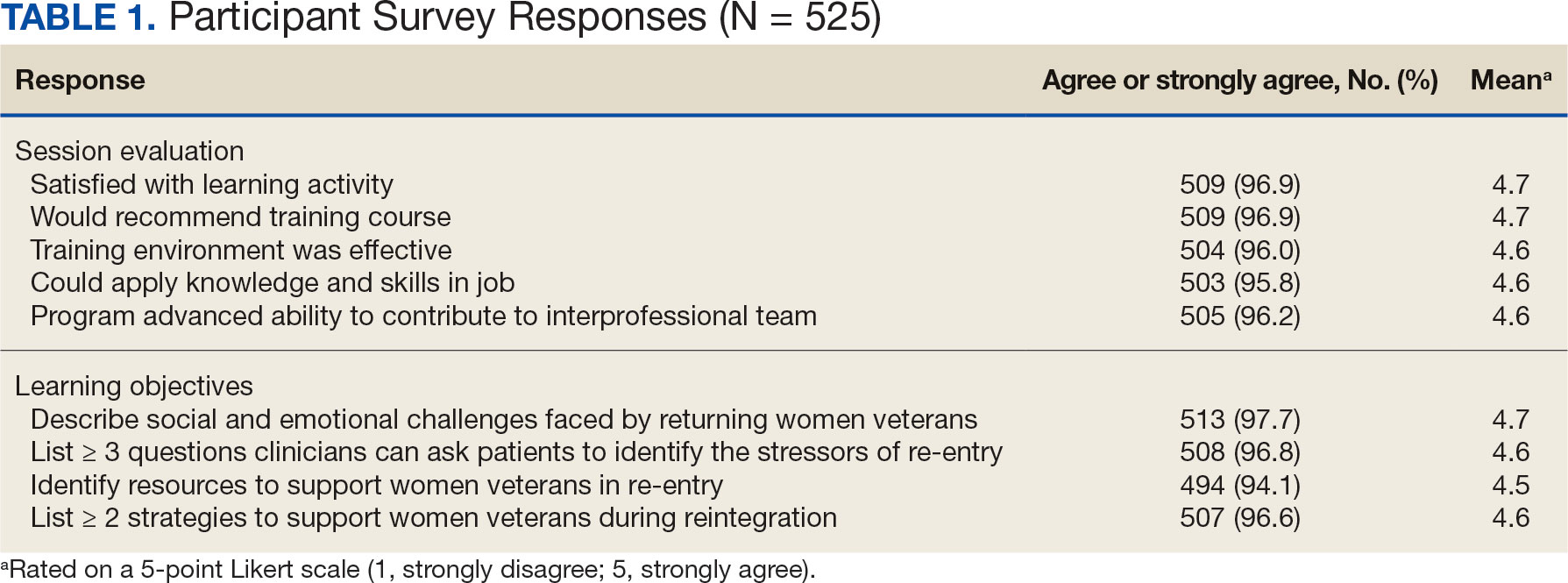

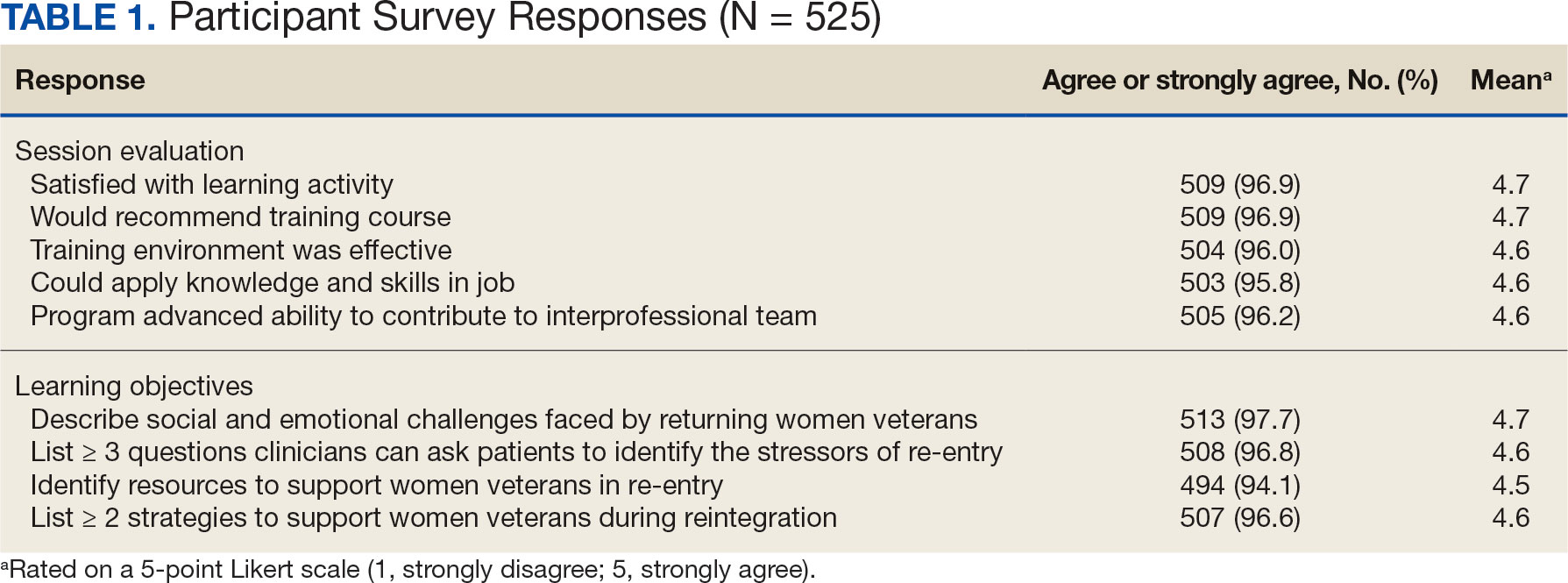

A total of 876 participants attended the virtual setting and 525 (59.9%) completed the immediate postevaluation survey. Respondents represented a variety of disciplines, including 179 nurses (34.1%), 100 social workers (19.0%), 65 physicians (12.4%), and 10 physician assistants (1.9%), with < 10% comprising counselors, dentists, dietitians, pharmacists, physical therapists, and psychologists. Nearly all participants reported satisfaction with the learning activity, would recommend it to others, and felt it advanced their knowledge, attitudes, and skills to better contribute to their VHA interprofessional team for patient care (Table 1). Similarly, participants reported a highlevel of agreement that the program satisfied the session-specific objectives. In response to an open-ended question on the standard VA evaluation regarding overall perceptions of the training, free-text responses included such statements as, “I think this should be mandatory training for all VA [clinicians]”; and “This webinar [opened] my mind to the various struggles women veterans may encounter when [they] return to civilian life and [increased] my understanding of how I could support.”

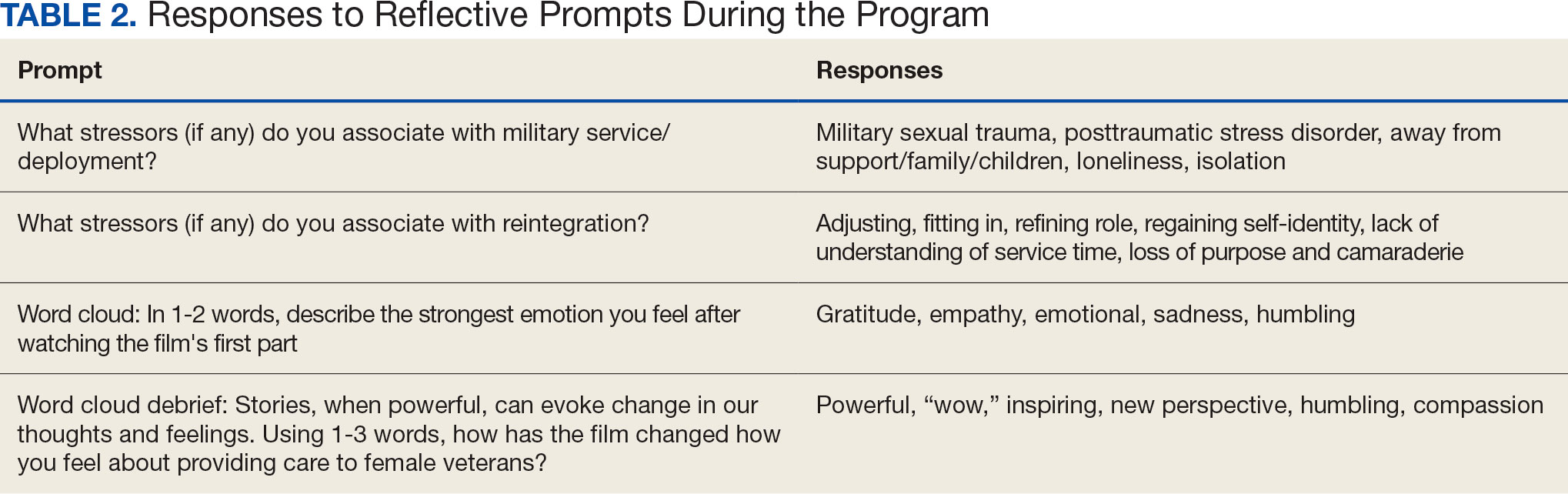

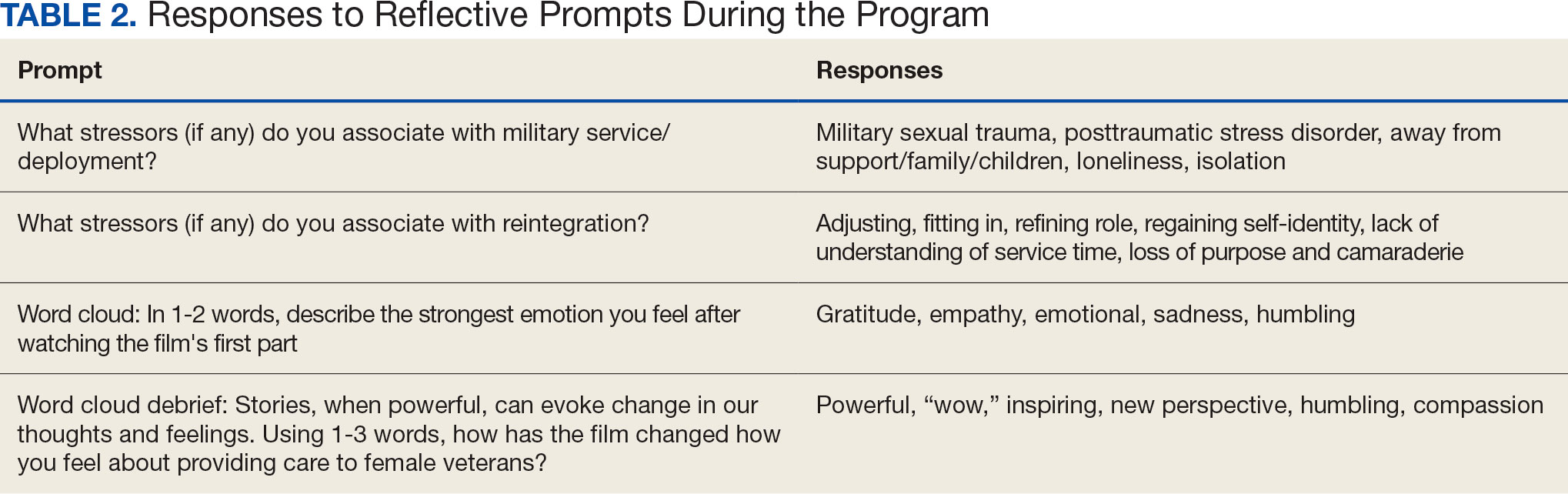

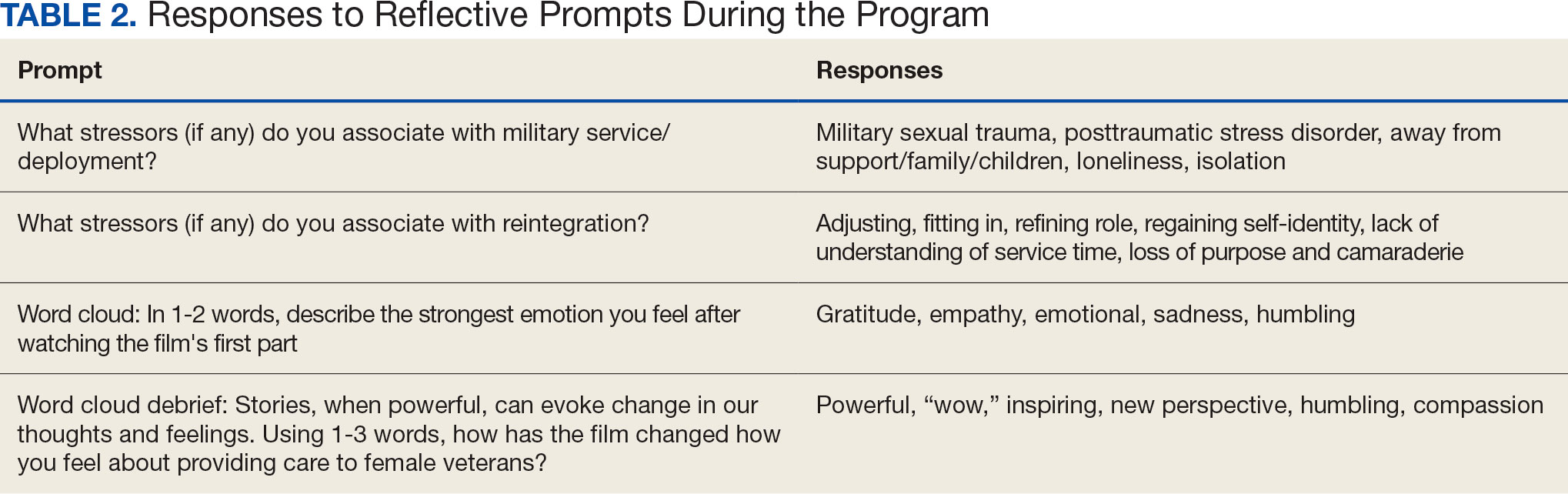

More than 1700 individual chat messages and > 80 spontaneous replies between participants were recorded during the interactive session (Table 2). Spontaneous quotes written in the chat included: “This is the best film representing the female veteran I have ever seen;” “Powerful and perspective changing;” “Thank you for sharing this incredible film;” and “I needed this to remind me to focus on woman veterans. Although our female veteran population is small it will remind me daily of their dedication, recognizing that there are so many facets of making the ultimate sacrifice.” Several participants said such programming should be a mandatory component of VA new employee orientation.

DISCUSSION

Clinician burnout diminishes empathetic patient-physician engagement. Patients’ stories are a known, powerful way to evoke empathy. This session provides one of the first examples of a straightforward approach to delivering a medical humanities intervention to a large audience via virtual platform. As measured by its high engagement, participant satisfaction, and narrative evaluations, this model was successful in evoking empathy and reinforcing the core VHA values for patient care: integrity, commitment, advocacy, respect, and excellence.

Rates of burnout and disengagement among PCPs are high and increased during the COVID-19 pandemic.2 This curriculum used a synchronous, narrative-based approach during work hours to address burnout. Lack of empathy is a cause and consequence of burnout and disengagement. Narrative approaches, especially those evoking patients’ stories can evoke empathy and help counteract such burnout. This curriculum demonstrates one of the first large-scale, narrative-based, virtual-platform approaches to utilizing patients’ stories for positive clinician impact, as evidenced by the extensive participation, engagement, and satisfaction of participants.

Individuals interested in implementing a similar program should consider common barriers, including time constraints, advertising, and clinician buy-in. Several key factors led to the successful implementation of this program. First, partnering with established educational efforts related to improving care for veterans provided time to implement the program and establish mechanisms for advertising. The VHA is a mission-driven organization; directly tying this intervention to the mission likely contributed to participant buy-in and programmatic success. Further, by partnering with established educational efforts, this session was conducted during business hours, allowing for widespread participation.

A diverse group of VHA clinicians were actively engaged throughout the session. Chat data demonstrated not only numerous responses to directed prompts, but also a larger extemporaneous conversation among participants. Additionally, it is clear participants were deeply engaged with the material. The quality of participant responses demonstrates the impact of narrative stories and included a new respect for our shared patients, a sense of humbleness as it relates to the women veteran experience, and a sense of pride in both the VHA mission and their roles as a part of the organization.

This session did not end with traditional take-home skills or reference handout resources typical of continuing education. This was intentional; the intended take-home message was the evoked emotional response and resultant perspective shift. The impact of this session on patient care will be examined in a forthcoming qualitative analysis of participants written reflections.

Limitations

Some participants noted that the chat could be distracting from the film. Others described that virtually attending the session allowed increased opportunity for interruption by ongoing patient care responsibilities, resulting in diverted attention. Many participants were granted protected time to attend this continuing education session; however, this was not always the case. Additionally, this evaluation is limited, as 40% of participants elected to not complete the postevent survey. The individuals who choose to respond may have been more engaged with the content or felt more strongly about the impact of the session. However, the volume of chat engagement during the session suggests strong participant involvement. The analysis was also limited by an electronic survey which did not allow more granular assessment of the data.

This session also raised an ethical consideration. The film evoked very strong emotional responses which, for some, were challenging to attend to personally in a large-scale virtual environment. Established clinician resources were highlighted during the session that were available for any participant who needed additional support. Participants were also encouraged to step away and process their emotions, if needed. Future interactions of this session might consider improved interparticipant chat management and upfront warnings about the emotional impact of the film accompanied by proactive dissemination of resources for participant support. One example of such resources includes breakout rooms facilitated by trained counselors. Prompts might also be adjusted to allow for more guided interparticipant engagement; facilitation can be brief as participants’ responses often carry the conversation.

CONCLUSIONS

This study shows that a large-scale, virtual medical humanities intervention is not only possible but well received, as evidenced by both quantity and quality of participant responses and engagement. The narrative approach of hearing patients’ stories, as portrayed in Journey to Normal, was found to be satisfying and appreciated by participants. Such an intervention has the potential to evoke empathy and help counteract burnout and disengagement among clinicians. This study directly aligned to the greater mission of the VHA: to improve quality medical care for all veterans, including women veterans, a subset population that is often overlooked. Organizations beyond the VHA may wish to leverage virtual learning as a mechanism to offer medical humanities to a wider audience. To optimize success, future programs should be tied to organizational missions, highlight patient voices and stories, and utilize platforms that allow for participant interactivity. Through virtual platforms, the medical humanities can reach a broader audience without detracting from its impact.

- Van Wert MJ, Gandhi S, Gupta I, et al. Healthcare worker mental health after the initial peak of the COVID- 19 pandemic: a US medical center cross-sectional survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(5):1169-1176. doi:10.1007/s11606-021-07251-0

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Signs. Health workers face a mental health crisis: workers report harassment, burnout, and poor mental health; supportive workplaces can help. Updated October 24, 2023. Accessed February 18, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/health-worker-mental-health/index.html

- Holmgren AJ, Downing NL, Tang M, Sharp C, Longhurst C, Huckman RS. Assessing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on clinician ambulatory electronic health record use. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2022;29(3):453-460. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocab268

- Apaydin EA, Mohr DC, Hamilton AB, Rose DE, Haskell S, Yano EM. Differences in burnout and intent to leave between women’s health and general primary care providers in the Veterans Health Administration. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(10):2382-2389. doi:10.1007/s11606-021-07133-5

- Willard-Grace R, Knox M, Huang B, Hammer H, Kivlahan C, Grumbach K. Burnout and health care workforce turnover. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(1):36-41. doi:10.1370/afm.2338

- Rinne ST, Mohr DC, Swamy L, Blok AC, Wong ES, Charns MP. National burnout trends among physicians working in the department of veterans affairs. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(5):1382-1388. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-05582-7

- Spinelli WM, Fernstrom KM, Galos DL, Britt HR. Extending our understanding of burnout and its associated factors: providers and staff in primary care clinics. Eval Health Prof. 2016;39(3):282-298. doi:10.1177/0163278716637900

- Abraham CM, Zheng K, Poghosyan L. Predictors and outcomes of burnout among primary care providers in the United States: a systematic review. Med Care Res Rev. 2020;77(5):387-401. doi:10.1177/1077558719888427

- Charon R, Williams P. Introduction: the humanities and medical education. Acad Med. 1995;70(9):758-760.

- Winkel AF, Yingling S, Jones A-A, Nicholson J. Reflection as a learning tool in graduate medical education: a systematic review. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(4):430-439. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-16-00500.1

- Charon R. The patient-physician relationship. Narrative medicine: a model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. JAMA. 2001;286(15):1897-1902. doi:10.1001/jama.286.15.1897

- DasGupta S, Charon R. Personal illness narratives: using reflective writing to teach empathy. Acad Med. 2004; 79(4):351-356. doi:10.1097/00001888-200404000-00013

- Liao JM, Secemsky BJ. The value of narrative medical writing in internal medicine residency. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(11):1707-1710. doi:10.1007/s11606-015-3460-x

- Branch WT, Kern D, Haidet P, et al. The patient-physician relationship. Teaching the human dimensions of care in clinical settings. JAMA. 2001;286(9):1067-1074. doi:10.1001/jama.286.9.1067

- Roberts TJ, Ringler T, Krahn D, Ahearn E. The my life, my story program: sustained impact of veterans’ personal narratives on healthcare providers 5 years after implementation. Health Commun. 2021;36(7):829-836. doi:10.1080/10410236.2020.1719316

- Lam JA, Feingold-Link M, Noguchi J, et al. My life, my story: integrating a life story narrative component into medical student curricula. MedEdPORTAL. 2022;18:11211. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11211

The COVID-19 pandemic presented stressors for patients and health care professionals alike, and the prevalence of health care practitioner burnout and dissatisfaction has risen dramatically.1,2 This, in combination with an increasingly virtual interface between patients and care teams, has the potential to lead to increased depersonalization, anxiety, distress, and diminished overall well-being among clinicians.1,3 Within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), women’s health primary care practitioners (PCPs) are specially trained clinicians thatprovide comprehensive care to women veterans. Data suggest that women’s health PCPs may experience higher rates of burnout and attrition (14% per year) compared to general PCPs in VHA.4 Burnout among PCPs, especially those working at VHA, is well known and likely related to poor interdisciplinary team structure, limited administrative time, high patient complexity, and isolation from additional resources (eg, rural settings).4-7 Increased clinician burnout is associated with poorer quality of care and worsening quality of the doctor-patient relationship.8

The medical humanities can act as a countermeasure to clinician burnout.9,10 Studies have demonstrated that physicians who participate in the medical humanities are more empathic and experience less burnout.11,12 Engaging with patient stories through listening and writing has been a source of fulfillment for clinicians.13 Despite the benefits of narrative medicine, programs are often limited in scope in small face-to-face group settings during elective time or outside work hours.14 The COVID-19 pandemic presented significant challenges to implementing such programming. The VHA is a large health care system with many rural locations, which further limits the availability of traditional small-group and face-to-face trainings. Few studies describe large-scale medical humanities training in virtual learning environments.

NARRATIVE MEDICINE EVENT

To improve satisfaction and engagement among PCPs who care for women veterans, we developed, implemented, and evaluated a large-scale, virtual, interprofessional narrative medicine event aimed at achieving the following: (1) gain a deeper appreciation of the impact of deployments on women veterans; (2) describe the social and emotional challenges faced by women veterans returning from deployment (reintegration); (3) identify strategies to support veterans during reintegration; (4) apply narrative medicine techniques on a large-scale, virtual platform; and (5) assess clinician engagement and satisfaction following participation. We hypothesized that clinician satisfaction and appreciation would improve with a better understanding of the unique complexities of deployment and reintegration faced by women veterans. Utilizing a novel, humanities-based intervention would lead to strong engagement and interaction from participants.

Setting

A 3-hour virtual session was conducted on November 15, 2022, for an interdisciplinary audience. This included physicians and trainees in medicine and behavioral health, nurse practitioners, social workers, dieticians, nurses, and clinical support staff. The training was advertised via emails through established mailing lists and newsletters, reaching a large interdisciplinary VHA audience 90 days prior to the event. This allowed potential participants to dedicate time to attend the session. The training was open to all VHA employees, with no inclusion or exclusion criteria for either the training or the evaluation. The training was delivered within existing space utilized for continuing medical education in women’s health.

For the session, the 93-minute documentary Journey to Normal (jtninc.org) was chosen because it focused on the impact of deployment on women veterans and their experiences when returning home. The film follows the stories of several women veterans through combat and reintegration. The screening was split into 2 segments given the emotional impact and length of the documentary.

A facilitator opened the session by reading a series of reflective prompts centered on women veteran deployment, reintegration, and the stressors surrounding these transitions. The initial prompt served to familiarize participants with the session’s interactive components. Additional prompts were interspersed and discussed in real time and were chosen to mirror the major themes of the documentary: the emotional and psychological impact of deployment and reintegration for women veterans. Short responses and word cloud generation were used and debriefed synchronously to encourage ongoing engagement. Participants responded to prompts through anonymous polling and the chat function of the virtual platform.

During intermission, we introduced My Life, My Story (MLMS). MLMS is a VHA initiative started in 2013 that, with the veteran’s permission, shares a piece of a veteran’s life story with their health care practitioner in their medical chart.15 Evaluation of MLMS has demonstrated positive impacts on assessments of patient-clinician connection.16 The MLMS goal to improve patient-centered care competencies by learning stories of veterans aligned with the overarching goals of this program. Following the film, participants were given 10 minutes to respond to a final reflective prompt. The session ended with a review of existing VHA resources to support returning veterans, followed by a question-and-answer session conducted via chat.

We used the Brightcove virtual platform to stream this program, which facilitated significant interaction between participants and facilitators, as well as between participants themselves. In addition to posing questions to the session leaders, participants could directly respond to each other’s comments within the chat function and also upvote/downvote or emphasize others’ comments.

Evaluation

The evaluation schema was 2-fold. Because this session was presented as a part of the national VA Women’s Health webinar series, a standard evaluation was dictated by the VHA Employee Education System. This survey was electronically disseminated and included questions on occupational category and overall satisfaction, plus 9 standard evaluation questions and 4 program-specific questions tied to the workshop objectives. The standard evaluation questions assessed participant satisfaction with the training, satisfaction with the training environment, and appropriateness of the content. The programspecific questions asked the participants whether the session met the stated learning objectives. All questions used a 5-point Likert scale (1, strongly disagree; 5, strongly agree). Descriptive statistics were used for analysis. Individual chat messages and spontaneous replies were analyzed as a surrogate measures of audience engagement. A qualitative analysis of participants’ final reflections to assess for attitudes related to patient care, empathy, and burnout following participation in this curriculum is forthcoming.

A total of 876 participants attended the virtual setting and 525 (59.9%) completed the immediate postevaluation survey. Respondents represented a variety of disciplines, including 179 nurses (34.1%), 100 social workers (19.0%), 65 physicians (12.4%), and 10 physician assistants (1.9%), with < 10% comprising counselors, dentists, dietitians, pharmacists, physical therapists, and psychologists. Nearly all participants reported satisfaction with the learning activity, would recommend it to others, and felt it advanced their knowledge, attitudes, and skills to better contribute to their VHA interprofessional team for patient care (Table 1). Similarly, participants reported a highlevel of agreement that the program satisfied the session-specific objectives. In response to an open-ended question on the standard VA evaluation regarding overall perceptions of the training, free-text responses included such statements as, “I think this should be mandatory training for all VA [clinicians]”; and “This webinar [opened] my mind to the various struggles women veterans may encounter when [they] return to civilian life and [increased] my understanding of how I could support.”

More than 1700 individual chat messages and > 80 spontaneous replies between participants were recorded during the interactive session (Table 2). Spontaneous quotes written in the chat included: “This is the best film representing the female veteran I have ever seen;” “Powerful and perspective changing;” “Thank you for sharing this incredible film;” and “I needed this to remind me to focus on woman veterans. Although our female veteran population is small it will remind me daily of their dedication, recognizing that there are so many facets of making the ultimate sacrifice.” Several participants said such programming should be a mandatory component of VA new employee orientation.

DISCUSSION

Clinician burnout diminishes empathetic patient-physician engagement. Patients’ stories are a known, powerful way to evoke empathy. This session provides one of the first examples of a straightforward approach to delivering a medical humanities intervention to a large audience via virtual platform. As measured by its high engagement, participant satisfaction, and narrative evaluations, this model was successful in evoking empathy and reinforcing the core VHA values for patient care: integrity, commitment, advocacy, respect, and excellence.

Rates of burnout and disengagement among PCPs are high and increased during the COVID-19 pandemic.2 This curriculum used a synchronous, narrative-based approach during work hours to address burnout. Lack of empathy is a cause and consequence of burnout and disengagement. Narrative approaches, especially those evoking patients’ stories can evoke empathy and help counteract such burnout. This curriculum demonstrates one of the first large-scale, narrative-based, virtual-platform approaches to utilizing patients’ stories for positive clinician impact, as evidenced by the extensive participation, engagement, and satisfaction of participants.

Individuals interested in implementing a similar program should consider common barriers, including time constraints, advertising, and clinician buy-in. Several key factors led to the successful implementation of this program. First, partnering with established educational efforts related to improving care for veterans provided time to implement the program and establish mechanisms for advertising. The VHA is a mission-driven organization; directly tying this intervention to the mission likely contributed to participant buy-in and programmatic success. Further, by partnering with established educational efforts, this session was conducted during business hours, allowing for widespread participation.

A diverse group of VHA clinicians were actively engaged throughout the session. Chat data demonstrated not only numerous responses to directed prompts, but also a larger extemporaneous conversation among participants. Additionally, it is clear participants were deeply engaged with the material. The quality of participant responses demonstrates the impact of narrative stories and included a new respect for our shared patients, a sense of humbleness as it relates to the women veteran experience, and a sense of pride in both the VHA mission and their roles as a part of the organization.

This session did not end with traditional take-home skills or reference handout resources typical of continuing education. This was intentional; the intended take-home message was the evoked emotional response and resultant perspective shift. The impact of this session on patient care will be examined in a forthcoming qualitative analysis of participants written reflections.

Limitations

Some participants noted that the chat could be distracting from the film. Others described that virtually attending the session allowed increased opportunity for interruption by ongoing patient care responsibilities, resulting in diverted attention. Many participants were granted protected time to attend this continuing education session; however, this was not always the case. Additionally, this evaluation is limited, as 40% of participants elected to not complete the postevent survey. The individuals who choose to respond may have been more engaged with the content or felt more strongly about the impact of the session. However, the volume of chat engagement during the session suggests strong participant involvement. The analysis was also limited by an electronic survey which did not allow more granular assessment of the data.

This session also raised an ethical consideration. The film evoked very strong emotional responses which, for some, were challenging to attend to personally in a large-scale virtual environment. Established clinician resources were highlighted during the session that were available for any participant who needed additional support. Participants were also encouraged to step away and process their emotions, if needed. Future interactions of this session might consider improved interparticipant chat management and upfront warnings about the emotional impact of the film accompanied by proactive dissemination of resources for participant support. One example of such resources includes breakout rooms facilitated by trained counselors. Prompts might also be adjusted to allow for more guided interparticipant engagement; facilitation can be brief as participants’ responses often carry the conversation.

CONCLUSIONS

This study shows that a large-scale, virtual medical humanities intervention is not only possible but well received, as evidenced by both quantity and quality of participant responses and engagement. The narrative approach of hearing patients’ stories, as portrayed in Journey to Normal, was found to be satisfying and appreciated by participants. Such an intervention has the potential to evoke empathy and help counteract burnout and disengagement among clinicians. This study directly aligned to the greater mission of the VHA: to improve quality medical care for all veterans, including women veterans, a subset population that is often overlooked. Organizations beyond the VHA may wish to leverage virtual learning as a mechanism to offer medical humanities to a wider audience. To optimize success, future programs should be tied to organizational missions, highlight patient voices and stories, and utilize platforms that allow for participant interactivity. Through virtual platforms, the medical humanities can reach a broader audience without detracting from its impact.

The COVID-19 pandemic presented stressors for patients and health care professionals alike, and the prevalence of health care practitioner burnout and dissatisfaction has risen dramatically.1,2 This, in combination with an increasingly virtual interface between patients and care teams, has the potential to lead to increased depersonalization, anxiety, distress, and diminished overall well-being among clinicians.1,3 Within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), women’s health primary care practitioners (PCPs) are specially trained clinicians thatprovide comprehensive care to women veterans. Data suggest that women’s health PCPs may experience higher rates of burnout and attrition (14% per year) compared to general PCPs in VHA.4 Burnout among PCPs, especially those working at VHA, is well known and likely related to poor interdisciplinary team structure, limited administrative time, high patient complexity, and isolation from additional resources (eg, rural settings).4-7 Increased clinician burnout is associated with poorer quality of care and worsening quality of the doctor-patient relationship.8

The medical humanities can act as a countermeasure to clinician burnout.9,10 Studies have demonstrated that physicians who participate in the medical humanities are more empathic and experience less burnout.11,12 Engaging with patient stories through listening and writing has been a source of fulfillment for clinicians.13 Despite the benefits of narrative medicine, programs are often limited in scope in small face-to-face group settings during elective time or outside work hours.14 The COVID-19 pandemic presented significant challenges to implementing such programming. The VHA is a large health care system with many rural locations, which further limits the availability of traditional small-group and face-to-face trainings. Few studies describe large-scale medical humanities training in virtual learning environments.

NARRATIVE MEDICINE EVENT

To improve satisfaction and engagement among PCPs who care for women veterans, we developed, implemented, and evaluated a large-scale, virtual, interprofessional narrative medicine event aimed at achieving the following: (1) gain a deeper appreciation of the impact of deployments on women veterans; (2) describe the social and emotional challenges faced by women veterans returning from deployment (reintegration); (3) identify strategies to support veterans during reintegration; (4) apply narrative medicine techniques on a large-scale, virtual platform; and (5) assess clinician engagement and satisfaction following participation. We hypothesized that clinician satisfaction and appreciation would improve with a better understanding of the unique complexities of deployment and reintegration faced by women veterans. Utilizing a novel, humanities-based intervention would lead to strong engagement and interaction from participants.

Setting

A 3-hour virtual session was conducted on November 15, 2022, for an interdisciplinary audience. This included physicians and trainees in medicine and behavioral health, nurse practitioners, social workers, dieticians, nurses, and clinical support staff. The training was advertised via emails through established mailing lists and newsletters, reaching a large interdisciplinary VHA audience 90 days prior to the event. This allowed potential participants to dedicate time to attend the session. The training was open to all VHA employees, with no inclusion or exclusion criteria for either the training or the evaluation. The training was delivered within existing space utilized for continuing medical education in women’s health.

For the session, the 93-minute documentary Journey to Normal (jtninc.org) was chosen because it focused on the impact of deployment on women veterans and their experiences when returning home. The film follows the stories of several women veterans through combat and reintegration. The screening was split into 2 segments given the emotional impact and length of the documentary.

A facilitator opened the session by reading a series of reflective prompts centered on women veteran deployment, reintegration, and the stressors surrounding these transitions. The initial prompt served to familiarize participants with the session’s interactive components. Additional prompts were interspersed and discussed in real time and were chosen to mirror the major themes of the documentary: the emotional and psychological impact of deployment and reintegration for women veterans. Short responses and word cloud generation were used and debriefed synchronously to encourage ongoing engagement. Participants responded to prompts through anonymous polling and the chat function of the virtual platform.

During intermission, we introduced My Life, My Story (MLMS). MLMS is a VHA initiative started in 2013 that, with the veteran’s permission, shares a piece of a veteran’s life story with their health care practitioner in their medical chart.15 Evaluation of MLMS has demonstrated positive impacts on assessments of patient-clinician connection.16 The MLMS goal to improve patient-centered care competencies by learning stories of veterans aligned with the overarching goals of this program. Following the film, participants were given 10 minutes to respond to a final reflective prompt. The session ended with a review of existing VHA resources to support returning veterans, followed by a question-and-answer session conducted via chat.

We used the Brightcove virtual platform to stream this program, which facilitated significant interaction between participants and facilitators, as well as between participants themselves. In addition to posing questions to the session leaders, participants could directly respond to each other’s comments within the chat function and also upvote/downvote or emphasize others’ comments.

Evaluation

The evaluation schema was 2-fold. Because this session was presented as a part of the national VA Women’s Health webinar series, a standard evaluation was dictated by the VHA Employee Education System. This survey was electronically disseminated and included questions on occupational category and overall satisfaction, plus 9 standard evaluation questions and 4 program-specific questions tied to the workshop objectives. The standard evaluation questions assessed participant satisfaction with the training, satisfaction with the training environment, and appropriateness of the content. The programspecific questions asked the participants whether the session met the stated learning objectives. All questions used a 5-point Likert scale (1, strongly disagree; 5, strongly agree). Descriptive statistics were used for analysis. Individual chat messages and spontaneous replies were analyzed as a surrogate measures of audience engagement. A qualitative analysis of participants’ final reflections to assess for attitudes related to patient care, empathy, and burnout following participation in this curriculum is forthcoming.

A total of 876 participants attended the virtual setting and 525 (59.9%) completed the immediate postevaluation survey. Respondents represented a variety of disciplines, including 179 nurses (34.1%), 100 social workers (19.0%), 65 physicians (12.4%), and 10 physician assistants (1.9%), with < 10% comprising counselors, dentists, dietitians, pharmacists, physical therapists, and psychologists. Nearly all participants reported satisfaction with the learning activity, would recommend it to others, and felt it advanced their knowledge, attitudes, and skills to better contribute to their VHA interprofessional team for patient care (Table 1). Similarly, participants reported a highlevel of agreement that the program satisfied the session-specific objectives. In response to an open-ended question on the standard VA evaluation regarding overall perceptions of the training, free-text responses included such statements as, “I think this should be mandatory training for all VA [clinicians]”; and “This webinar [opened] my mind to the various struggles women veterans may encounter when [they] return to civilian life and [increased] my understanding of how I could support.”

More than 1700 individual chat messages and > 80 spontaneous replies between participants were recorded during the interactive session (Table 2). Spontaneous quotes written in the chat included: “This is the best film representing the female veteran I have ever seen;” “Powerful and perspective changing;” “Thank you for sharing this incredible film;” and “I needed this to remind me to focus on woman veterans. Although our female veteran population is small it will remind me daily of their dedication, recognizing that there are so many facets of making the ultimate sacrifice.” Several participants said such programming should be a mandatory component of VA new employee orientation.

DISCUSSION

Clinician burnout diminishes empathetic patient-physician engagement. Patients’ stories are a known, powerful way to evoke empathy. This session provides one of the first examples of a straightforward approach to delivering a medical humanities intervention to a large audience via virtual platform. As measured by its high engagement, participant satisfaction, and narrative evaluations, this model was successful in evoking empathy and reinforcing the core VHA values for patient care: integrity, commitment, advocacy, respect, and excellence.

Rates of burnout and disengagement among PCPs are high and increased during the COVID-19 pandemic.2 This curriculum used a synchronous, narrative-based approach during work hours to address burnout. Lack of empathy is a cause and consequence of burnout and disengagement. Narrative approaches, especially those evoking patients’ stories can evoke empathy and help counteract such burnout. This curriculum demonstrates one of the first large-scale, narrative-based, virtual-platform approaches to utilizing patients’ stories for positive clinician impact, as evidenced by the extensive participation, engagement, and satisfaction of participants.

Individuals interested in implementing a similar program should consider common barriers, including time constraints, advertising, and clinician buy-in. Several key factors led to the successful implementation of this program. First, partnering with established educational efforts related to improving care for veterans provided time to implement the program and establish mechanisms for advertising. The VHA is a mission-driven organization; directly tying this intervention to the mission likely contributed to participant buy-in and programmatic success. Further, by partnering with established educational efforts, this session was conducted during business hours, allowing for widespread participation.

A diverse group of VHA clinicians were actively engaged throughout the session. Chat data demonstrated not only numerous responses to directed prompts, but also a larger extemporaneous conversation among participants. Additionally, it is clear participants were deeply engaged with the material. The quality of participant responses demonstrates the impact of narrative stories and included a new respect for our shared patients, a sense of humbleness as it relates to the women veteran experience, and a sense of pride in both the VHA mission and their roles as a part of the organization.

This session did not end with traditional take-home skills or reference handout resources typical of continuing education. This was intentional; the intended take-home message was the evoked emotional response and resultant perspective shift. The impact of this session on patient care will be examined in a forthcoming qualitative analysis of participants written reflections.

Limitations

Some participants noted that the chat could be distracting from the film. Others described that virtually attending the session allowed increased opportunity for interruption by ongoing patient care responsibilities, resulting in diverted attention. Many participants were granted protected time to attend this continuing education session; however, this was not always the case. Additionally, this evaluation is limited, as 40% of participants elected to not complete the postevent survey. The individuals who choose to respond may have been more engaged with the content or felt more strongly about the impact of the session. However, the volume of chat engagement during the session suggests strong participant involvement. The analysis was also limited by an electronic survey which did not allow more granular assessment of the data.

This session also raised an ethical consideration. The film evoked very strong emotional responses which, for some, were challenging to attend to personally in a large-scale virtual environment. Established clinician resources were highlighted during the session that were available for any participant who needed additional support. Participants were also encouraged to step away and process their emotions, if needed. Future interactions of this session might consider improved interparticipant chat management and upfront warnings about the emotional impact of the film accompanied by proactive dissemination of resources for participant support. One example of such resources includes breakout rooms facilitated by trained counselors. Prompts might also be adjusted to allow for more guided interparticipant engagement; facilitation can be brief as participants’ responses often carry the conversation.

CONCLUSIONS

This study shows that a large-scale, virtual medical humanities intervention is not only possible but well received, as evidenced by both quantity and quality of participant responses and engagement. The narrative approach of hearing patients’ stories, as portrayed in Journey to Normal, was found to be satisfying and appreciated by participants. Such an intervention has the potential to evoke empathy and help counteract burnout and disengagement among clinicians. This study directly aligned to the greater mission of the VHA: to improve quality medical care for all veterans, including women veterans, a subset population that is often overlooked. Organizations beyond the VHA may wish to leverage virtual learning as a mechanism to offer medical humanities to a wider audience. To optimize success, future programs should be tied to organizational missions, highlight patient voices and stories, and utilize platforms that allow for participant interactivity. Through virtual platforms, the medical humanities can reach a broader audience without detracting from its impact.

- Van Wert MJ, Gandhi S, Gupta I, et al. Healthcare worker mental health after the initial peak of the COVID- 19 pandemic: a US medical center cross-sectional survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(5):1169-1176. doi:10.1007/s11606-021-07251-0

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Signs. Health workers face a mental health crisis: workers report harassment, burnout, and poor mental health; supportive workplaces can help. Updated October 24, 2023. Accessed February 18, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/health-worker-mental-health/index.html

- Holmgren AJ, Downing NL, Tang M, Sharp C, Longhurst C, Huckman RS. Assessing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on clinician ambulatory electronic health record use. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2022;29(3):453-460. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocab268

- Apaydin EA, Mohr DC, Hamilton AB, Rose DE, Haskell S, Yano EM. Differences in burnout and intent to leave between women’s health and general primary care providers in the Veterans Health Administration. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(10):2382-2389. doi:10.1007/s11606-021-07133-5

- Willard-Grace R, Knox M, Huang B, Hammer H, Kivlahan C, Grumbach K. Burnout and health care workforce turnover. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(1):36-41. doi:10.1370/afm.2338

- Rinne ST, Mohr DC, Swamy L, Blok AC, Wong ES, Charns MP. National burnout trends among physicians working in the department of veterans affairs. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(5):1382-1388. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-05582-7

- Spinelli WM, Fernstrom KM, Galos DL, Britt HR. Extending our understanding of burnout and its associated factors: providers and staff in primary care clinics. Eval Health Prof. 2016;39(3):282-298. doi:10.1177/0163278716637900

- Abraham CM, Zheng K, Poghosyan L. Predictors and outcomes of burnout among primary care providers in the United States: a systematic review. Med Care Res Rev. 2020;77(5):387-401. doi:10.1177/1077558719888427

- Charon R, Williams P. Introduction: the humanities and medical education. Acad Med. 1995;70(9):758-760.

- Winkel AF, Yingling S, Jones A-A, Nicholson J. Reflection as a learning tool in graduate medical education: a systematic review. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(4):430-439. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-16-00500.1

- Charon R. The patient-physician relationship. Narrative medicine: a model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. JAMA. 2001;286(15):1897-1902. doi:10.1001/jama.286.15.1897

- DasGupta S, Charon R. Personal illness narratives: using reflective writing to teach empathy. Acad Med. 2004; 79(4):351-356. doi:10.1097/00001888-200404000-00013

- Liao JM, Secemsky BJ. The value of narrative medical writing in internal medicine residency. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(11):1707-1710. doi:10.1007/s11606-015-3460-x

- Branch WT, Kern D, Haidet P, et al. The patient-physician relationship. Teaching the human dimensions of care in clinical settings. JAMA. 2001;286(9):1067-1074. doi:10.1001/jama.286.9.1067

- Roberts TJ, Ringler T, Krahn D, Ahearn E. The my life, my story program: sustained impact of veterans’ personal narratives on healthcare providers 5 years after implementation. Health Commun. 2021;36(7):829-836. doi:10.1080/10410236.2020.1719316

- Lam JA, Feingold-Link M, Noguchi J, et al. My life, my story: integrating a life story narrative component into medical student curricula. MedEdPORTAL. 2022;18:11211. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11211

- Van Wert MJ, Gandhi S, Gupta I, et al. Healthcare worker mental health after the initial peak of the COVID- 19 pandemic: a US medical center cross-sectional survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(5):1169-1176. doi:10.1007/s11606-021-07251-0

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Signs. Health workers face a mental health crisis: workers report harassment, burnout, and poor mental health; supportive workplaces can help. Updated October 24, 2023. Accessed February 18, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/health-worker-mental-health/index.html

- Holmgren AJ, Downing NL, Tang M, Sharp C, Longhurst C, Huckman RS. Assessing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on clinician ambulatory electronic health record use. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2022;29(3):453-460. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocab268

- Apaydin EA, Mohr DC, Hamilton AB, Rose DE, Haskell S, Yano EM. Differences in burnout and intent to leave between women’s health and general primary care providers in the Veterans Health Administration. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(10):2382-2389. doi:10.1007/s11606-021-07133-5

- Willard-Grace R, Knox M, Huang B, Hammer H, Kivlahan C, Grumbach K. Burnout and health care workforce turnover. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(1):36-41. doi:10.1370/afm.2338

- Rinne ST, Mohr DC, Swamy L, Blok AC, Wong ES, Charns MP. National burnout trends among physicians working in the department of veterans affairs. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(5):1382-1388. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-05582-7

- Spinelli WM, Fernstrom KM, Galos DL, Britt HR. Extending our understanding of burnout and its associated factors: providers and staff in primary care clinics. Eval Health Prof. 2016;39(3):282-298. doi:10.1177/0163278716637900

- Abraham CM, Zheng K, Poghosyan L. Predictors and outcomes of burnout among primary care providers in the United States: a systematic review. Med Care Res Rev. 2020;77(5):387-401. doi:10.1177/1077558719888427

- Charon R, Williams P. Introduction: the humanities and medical education. Acad Med. 1995;70(9):758-760.

- Winkel AF, Yingling S, Jones A-A, Nicholson J. Reflection as a learning tool in graduate medical education: a systematic review. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(4):430-439. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-16-00500.1

- Charon R. The patient-physician relationship. Narrative medicine: a model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. JAMA. 2001;286(15):1897-1902. doi:10.1001/jama.286.15.1897

- DasGupta S, Charon R. Personal illness narratives: using reflective writing to teach empathy. Acad Med. 2004; 79(4):351-356. doi:10.1097/00001888-200404000-00013

- Liao JM, Secemsky BJ. The value of narrative medical writing in internal medicine residency. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(11):1707-1710. doi:10.1007/s11606-015-3460-x

- Branch WT, Kern D, Haidet P, et al. The patient-physician relationship. Teaching the human dimensions of care in clinical settings. JAMA. 2001;286(9):1067-1074. doi:10.1001/jama.286.9.1067

- Roberts TJ, Ringler T, Krahn D, Ahearn E. The my life, my story program: sustained impact of veterans’ personal narratives on healthcare providers 5 years after implementation. Health Commun. 2021;36(7):829-836. doi:10.1080/10410236.2020.1719316

- Lam JA, Feingold-Link M, Noguchi J, et al. My life, my story: integrating a life story narrative component into medical student curricula. MedEdPORTAL. 2022;18:11211. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11211

Hearing Patient Stories: Use of Medical Humanities on a Large-Scale, Virtual Platform to Improve Clinician Engagement

Hearing Patient Stories: Use of Medical Humanities on a Large-Scale, Virtual Platform to Improve Clinician Engagement

Gender and Hospital Medicine

From a new concept to 44,000 practitioners in just 18 years,[1] there is no doubt that the word hospitalist is synonymous with innovation, leadership, growth, and change. Yet 2 articles in this month's Journal of Hospital Medicine prove that even our new field faces age‐old problems. Although women comprise half of all academic hospitalist and general internal medicine faculty, Burden et al.[2] showed that female hospitalists are less likely than male hospitalists to be division or section heads of hospital medicine, speakers at national meetings, and first or last authors on both research publications and editorials. This is made more concerning given that women are more likely to choose academic hospital medicine careers,[3] as they represent one‐third of all hospitalists but half of the academic hospitalist workforce.[2, 3] Findings in general internal medicine were similar, except that equal numbers of women and men were national meeting speakers and first authors on research publications (but not editorials). Weaver et al.[4] shed even more light on this disparity, and found that female hospitalists made $14,581 less per year than their male counterparts, even after adjusting for relevant differences. Weaver and colleagues also found other gender‐specific differences: women worked more nights and had fewer billable encounters per hospitalist shift than men.

Unfortunately, these trends are not new or limited to hospital medicine. For decades, almost equal numbers of women and men have entered medical school,[5] yet women are under‐represented in high status specialties,[6] less likely to be first or senior authors on original research studies compared to men,[7] less likely to be promoted,[8] and women physicians are consistently paid less than men across specialties.[9, 10] Simple analyses have not yet explained these disparities. Compared with men, women have similar leadership aspirations[11, 12] and are at least as effective as leaders.[13, 14, 15] Yet equity has not been attained.

Implicit bias research suggests that gender stereotypes influence women at all career stages.[16, 17, 18] For example, an elegant study conducted by Correll et al. identified a motherhood penalty, where indicating membership in the elementary school parent‐teacher organization on one's curriculum vitae hurt women's chances of employment and pay, but actually helped men.[19] Gender stereotypes exist, even among those who do not support their content. The universal reinforcement of such stereotypes over time leads to implicit but prescriptive rules about how women and men should act.[20] In particular, communal behaviors, including being cooperative, kind, and understanding, are typically associated with women, and agentic behaviors, including being ambitious and acting as a leader, are considered appropriate for men.[21] This leads to the think leader, think male phenomena, where we automatically associate men with leadership and higher status tasks (like first authorship or speaker invitations).[22, 23] Furthermore, acting against the stereotype (eg, a woman showing anger[24] or negotiating for more pay[25] or a man showing sadness[26]) can negatively impact wage and employment. Expecting social censure for violating gender norms, women develop a fear of the backlash that alone may shape behavior such that women may not express interest in having a high salary or negotiate for a raise.[27, 28, 29]

The specific system and institutional barriers that prevent female hospitalists from receiving equal pay and opportunities for leadership are not known, but one can surmise they are similar to those found in other specialties.[10, 30, 31] The findings of the studies of Burden et al.[2] and Weaver et al.[4] invite investigation of new questions specific to hospital medicine. Why are women in hospital medicine working more night shifts? Does this impact leadership or scholarship opportunities? Why are women documenting less productivity? Are they spending more time with patients, as they do in other settings?[32] What influences their practice choice? We would like to believe that there is something about hospital medicine that can explain the gender differences identified in these 2 studies. However, these data should prompt a serious and thorough examination of our specialty. We must accept that despite being a new specialty and a change leader, hospital medicine may not have escaped systematic gender bias that constrains the full participation and advancement of women.

But we believe that hospitalistsinnovators and change leaders in medicinewill be spurred to action to address the possibility of gender inequities. We do not need to know all of the causes to begin to address disparities, of every type, on an individual, institutional, and national level. As individuals, we can acknowledge that there are implicit assumptions that influence our decision making. No matter how unintentional, and even conflicting with evidence, these assumptions can lead us to judge women as less capable leaders than men or to automatically envision a high salary for a woman and man as different amounts. However, these automatic gender biases function as habits of mind, so they can be broken like any other unwanted habit.[33] Institutionally, we can also hold ourselves accountable for transparency in mentorship, leadership, scholarship, promotions, and wages to ensure diverse representation. We should routinely examine our practices to ensure the equitable hiring, pay, and promotion of our workforce.[18] National organizations and their respective journals should actively pursue diverse representation in leadership and membership on boards and committees, award nominees and recipients, and opportunities for invited editorials. Hospital medicinebeing young, innovative, and committed to changeis uniquely well suited to lead the charge for workforce equity. We can, and will, show the rest of medicine how it is done.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. Milestones in the hospital medicine movement. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Web/About_SHM/Industry/shm_History.aspx. Accessed March 23, 2015.

- , , , et al. Gender disparities in leadership and scholarly productivity of academic hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(X):000–000.

- , , , , . Job characteristics, satisfaction, and burnout across hospitalist practice models. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:402–410.

- , , , . A matter of priorities? Exploring the persistent gender pay gap in hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):486–490.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Table 1: medical students, selected years, 1965–2013. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/download/411782/data/2014_table1.pdf. Accessed March 23, 2015.

- , , , . Sex, role models, and specialty choices among graduates of US medical schools in 2006‐2008. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218(3):345–352.

- , , , et al. The “Gender Gap” in authorship of academic medical literature—a 35‐year perspective. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(3):281–287.

- . Women physicians in academic medicine. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(6):399–405.

- , , , , , . Gender differences in the salaries of physician researchers. JAMA. 2012;307(22):2410–2417.

- , , , . The $16,819 pay gap for newly trained physicians: the unexplained trend of men earning more than women. Health Affairs. 2011;30(2):193–201.

- , , , , . Experiencing the culture of academic medicine: gender matters, a national study. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(2):201–207.

- , , , et al. Gender differences in academic advancement: patterns, causes, and potential solutions in one US College of Medicine. Acad Med. 2003;78(5):500–508.

- . Faculty and staff members perceptions of effective leadership: are there differences between men and women leaders? Equity Excell Educ. 2003;36(1):71–81.

- , , . Transformational, transactional, and lasissez‐faire leadership styles: a meta‐analysis comparing women and men. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(4):569–591.

- , , . A qualitative study of faculty members' views of women chairs. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2010;19(3):533–546.

- , . Stuck in the out‐group: Jennifer can't grow up, Jane's invisible, and Janet's over the hill. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2014;23(6):481–484.

- , . Women and the labyrinth of leadership. Harv Bus Rev. 2007;85(9):62–71.

- , , . Interventions that affect gender bias in hiring: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2009;84(10):1440–1446.

- , , . Getting a job: is there a motherhood penalty? Am J Sociol. 2017;112(5):1297–1339.

- , , , , . Afraid of being “witchy with a ‘b’”: a qualitative study of how gender influences residents' experiences leading cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1276–1281.

- . The measurement of psychological androgyny. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1974;42:155–162.

- , , , . Think manager—think male: A global phenomenon? J Organ Behav. 1996;17(1):33–41.

- , , , . Are leader stereotypes masculine? A meta‐analysis of three research paradigms. Psychol Bull. 2011;137(4):616–642.

- , . Can an angry woman get ahead? Status conferral, gender, and expression of emotion in the workplace. Psychol Sci. 2008;19(3):268–275.

- , , . Social incentives for gender differences in the propensity to initiate negations: sometimes it does hurt to ask. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 2007;103:84–103.

- . Anger and advancement versus sadness and subjugation: the effect of negative emotion expressions on social status conferral. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2001;80(1):86–94.

- , , . Battle of the sexes: gender stereotype confirmation and reactance in negotiations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2001;80(6):942–958.

- , . Prejudice toward female leaders: Backlash effects and women's impression management dilemma. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2010;4(10):807–820.

- . Commentary: deconstructing gender difference. Acad Med. 2010;85(4):575–577.

- , , , . Organizational climate and family life: how these factors affect the status of women faculty at one medical school. Acad Med. 2009;84(1):87–94.

- , , , , , . Survey results: a decade of change in professional life in cardiology: a 2008 report of the ACC women in cardiology council. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(25):2215–2226.

- , , , , . Effect of physicians' gender on communication and consultation length: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2013;18:242–248.

- , , , et al. The effect of an intervention to break the gender bias habit for faculty at one institution: a cluster randomized, controlled trial. Acad Med. 2015;90(2):221–230.

From a new concept to 44,000 practitioners in just 18 years,[1] there is no doubt that the word hospitalist is synonymous with innovation, leadership, growth, and change. Yet 2 articles in this month's Journal of Hospital Medicine prove that even our new field faces age‐old problems. Although women comprise half of all academic hospitalist and general internal medicine faculty, Burden et al.[2] showed that female hospitalists are less likely than male hospitalists to be division or section heads of hospital medicine, speakers at national meetings, and first or last authors on both research publications and editorials. This is made more concerning given that women are more likely to choose academic hospital medicine careers,[3] as they represent one‐third of all hospitalists but half of the academic hospitalist workforce.[2, 3] Findings in general internal medicine were similar, except that equal numbers of women and men were national meeting speakers and first authors on research publications (but not editorials). Weaver et al.[4] shed even more light on this disparity, and found that female hospitalists made $14,581 less per year than their male counterparts, even after adjusting for relevant differences. Weaver and colleagues also found other gender‐specific differences: women worked more nights and had fewer billable encounters per hospitalist shift than men.

Unfortunately, these trends are not new or limited to hospital medicine. For decades, almost equal numbers of women and men have entered medical school,[5] yet women are under‐represented in high status specialties,[6] less likely to be first or senior authors on original research studies compared to men,[7] less likely to be promoted,[8] and women physicians are consistently paid less than men across specialties.[9, 10] Simple analyses have not yet explained these disparities. Compared with men, women have similar leadership aspirations[11, 12] and are at least as effective as leaders.[13, 14, 15] Yet equity has not been attained.

Implicit bias research suggests that gender stereotypes influence women at all career stages.[16, 17, 18] For example, an elegant study conducted by Correll et al. identified a motherhood penalty, where indicating membership in the elementary school parent‐teacher organization on one's curriculum vitae hurt women's chances of employment and pay, but actually helped men.[19] Gender stereotypes exist, even among those who do not support their content. The universal reinforcement of such stereotypes over time leads to implicit but prescriptive rules about how women and men should act.[20] In particular, communal behaviors, including being cooperative, kind, and understanding, are typically associated with women, and agentic behaviors, including being ambitious and acting as a leader, are considered appropriate for men.[21] This leads to the think leader, think male phenomena, where we automatically associate men with leadership and higher status tasks (like first authorship or speaker invitations).[22, 23] Furthermore, acting against the stereotype (eg, a woman showing anger[24] or negotiating for more pay[25] or a man showing sadness[26]) can negatively impact wage and employment. Expecting social censure for violating gender norms, women develop a fear of the backlash that alone may shape behavior such that women may not express interest in having a high salary or negotiate for a raise.[27, 28, 29]

The specific system and institutional barriers that prevent female hospitalists from receiving equal pay and opportunities for leadership are not known, but one can surmise they are similar to those found in other specialties.[10, 30, 31] The findings of the studies of Burden et al.[2] and Weaver et al.[4] invite investigation of new questions specific to hospital medicine. Why are women in hospital medicine working more night shifts? Does this impact leadership or scholarship opportunities? Why are women documenting less productivity? Are they spending more time with patients, as they do in other settings?[32] What influences their practice choice? We would like to believe that there is something about hospital medicine that can explain the gender differences identified in these 2 studies. However, these data should prompt a serious and thorough examination of our specialty. We must accept that despite being a new specialty and a change leader, hospital medicine may not have escaped systematic gender bias that constrains the full participation and advancement of women.

But we believe that hospitalistsinnovators and change leaders in medicinewill be spurred to action to address the possibility of gender inequities. We do not need to know all of the causes to begin to address disparities, of every type, on an individual, institutional, and national level. As individuals, we can acknowledge that there are implicit assumptions that influence our decision making. No matter how unintentional, and even conflicting with evidence, these assumptions can lead us to judge women as less capable leaders than men or to automatically envision a high salary for a woman and man as different amounts. However, these automatic gender biases function as habits of mind, so they can be broken like any other unwanted habit.[33] Institutionally, we can also hold ourselves accountable for transparency in mentorship, leadership, scholarship, promotions, and wages to ensure diverse representation. We should routinely examine our practices to ensure the equitable hiring, pay, and promotion of our workforce.[18] National organizations and their respective journals should actively pursue diverse representation in leadership and membership on boards and committees, award nominees and recipients, and opportunities for invited editorials. Hospital medicinebeing young, innovative, and committed to changeis uniquely well suited to lead the charge for workforce equity. We can, and will, show the rest of medicine how it is done.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

From a new concept to 44,000 practitioners in just 18 years,[1] there is no doubt that the word hospitalist is synonymous with innovation, leadership, growth, and change. Yet 2 articles in this month's Journal of Hospital Medicine prove that even our new field faces age‐old problems. Although women comprise half of all academic hospitalist and general internal medicine faculty, Burden et al.[2] showed that female hospitalists are less likely than male hospitalists to be division or section heads of hospital medicine, speakers at national meetings, and first or last authors on both research publications and editorials. This is made more concerning given that women are more likely to choose academic hospital medicine careers,[3] as they represent one‐third of all hospitalists but half of the academic hospitalist workforce.[2, 3] Findings in general internal medicine were similar, except that equal numbers of women and men were national meeting speakers and first authors on research publications (but not editorials). Weaver et al.[4] shed even more light on this disparity, and found that female hospitalists made $14,581 less per year than their male counterparts, even after adjusting for relevant differences. Weaver and colleagues also found other gender‐specific differences: women worked more nights and had fewer billable encounters per hospitalist shift than men.

Unfortunately, these trends are not new or limited to hospital medicine. For decades, almost equal numbers of women and men have entered medical school,[5] yet women are under‐represented in high status specialties,[6] less likely to be first or senior authors on original research studies compared to men,[7] less likely to be promoted,[8] and women physicians are consistently paid less than men across specialties.[9, 10] Simple analyses have not yet explained these disparities. Compared with men, women have similar leadership aspirations[11, 12] and are at least as effective as leaders.[13, 14, 15] Yet equity has not been attained.

Implicit bias research suggests that gender stereotypes influence women at all career stages.[16, 17, 18] For example, an elegant study conducted by Correll et al. identified a motherhood penalty, where indicating membership in the elementary school parent‐teacher organization on one's curriculum vitae hurt women's chances of employment and pay, but actually helped men.[19] Gender stereotypes exist, even among those who do not support their content. The universal reinforcement of such stereotypes over time leads to implicit but prescriptive rules about how women and men should act.[20] In particular, communal behaviors, including being cooperative, kind, and understanding, are typically associated with women, and agentic behaviors, including being ambitious and acting as a leader, are considered appropriate for men.[21] This leads to the think leader, think male phenomena, where we automatically associate men with leadership and higher status tasks (like first authorship or speaker invitations).[22, 23] Furthermore, acting against the stereotype (eg, a woman showing anger[24] or negotiating for more pay[25] or a man showing sadness[26]) can negatively impact wage and employment. Expecting social censure for violating gender norms, women develop a fear of the backlash that alone may shape behavior such that women may not express interest in having a high salary or negotiate for a raise.[27, 28, 29]

The specific system and institutional barriers that prevent female hospitalists from receiving equal pay and opportunities for leadership are not known, but one can surmise they are similar to those found in other specialties.[10, 30, 31] The findings of the studies of Burden et al.[2] and Weaver et al.[4] invite investigation of new questions specific to hospital medicine. Why are women in hospital medicine working more night shifts? Does this impact leadership or scholarship opportunities? Why are women documenting less productivity? Are they spending more time with patients, as they do in other settings?[32] What influences their practice choice? We would like to believe that there is something about hospital medicine that can explain the gender differences identified in these 2 studies. However, these data should prompt a serious and thorough examination of our specialty. We must accept that despite being a new specialty and a change leader, hospital medicine may not have escaped systematic gender bias that constrains the full participation and advancement of women.

But we believe that hospitalistsinnovators and change leaders in medicinewill be spurred to action to address the possibility of gender inequities. We do not need to know all of the causes to begin to address disparities, of every type, on an individual, institutional, and national level. As individuals, we can acknowledge that there are implicit assumptions that influence our decision making. No matter how unintentional, and even conflicting with evidence, these assumptions can lead us to judge women as less capable leaders than men or to automatically envision a high salary for a woman and man as different amounts. However, these automatic gender biases function as habits of mind, so they can be broken like any other unwanted habit.[33] Institutionally, we can also hold ourselves accountable for transparency in mentorship, leadership, scholarship, promotions, and wages to ensure diverse representation. We should routinely examine our practices to ensure the equitable hiring, pay, and promotion of our workforce.[18] National organizations and their respective journals should actively pursue diverse representation in leadership and membership on boards and committees, award nominees and recipients, and opportunities for invited editorials. Hospital medicinebeing young, innovative, and committed to changeis uniquely well suited to lead the charge for workforce equity. We can, and will, show the rest of medicine how it is done.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. Milestones in the hospital medicine movement. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Web/About_SHM/Industry/shm_History.aspx. Accessed March 23, 2015.

- , , , et al. Gender disparities in leadership and scholarly productivity of academic hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(X):000–000.

- , , , , . Job characteristics, satisfaction, and burnout across hospitalist practice models. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:402–410.

- , , , . A matter of priorities? Exploring the persistent gender pay gap in hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):486–490.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Table 1: medical students, selected years, 1965–2013. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/download/411782/data/2014_table1.pdf. Accessed March 23, 2015.

- , , , . Sex, role models, and specialty choices among graduates of US medical schools in 2006‐2008. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218(3):345–352.

- , , , et al. The “Gender Gap” in authorship of academic medical literature—a 35‐year perspective. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(3):281–287.

- . Women physicians in academic medicine. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(6):399–405.

- , , , , , . Gender differences in the salaries of physician researchers. JAMA. 2012;307(22):2410–2417.

- , , , . The $16,819 pay gap for newly trained physicians: the unexplained trend of men earning more than women. Health Affairs. 2011;30(2):193–201.

- , , , , . Experiencing the culture of academic medicine: gender matters, a national study. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(2):201–207.

- , , , et al. Gender differences in academic advancement: patterns, causes, and potential solutions in one US College of Medicine. Acad Med. 2003;78(5):500–508.

- . Faculty and staff members perceptions of effective leadership: are there differences between men and women leaders? Equity Excell Educ. 2003;36(1):71–81.