User login

Beyond the Razor: Managing Pseudofolliculitis Barbae in Skin of Color

Beyond the Razor: Managing Pseudofolliculitis Barbae in Skin of Color

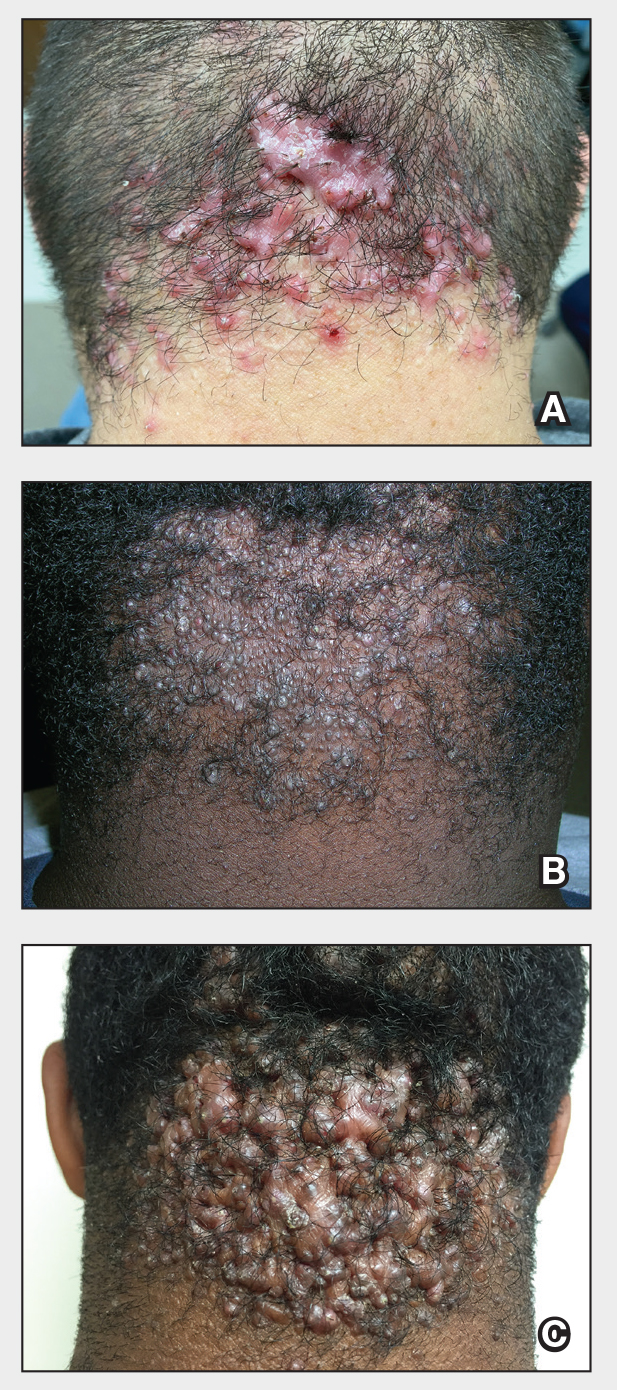

THE COMPARISON

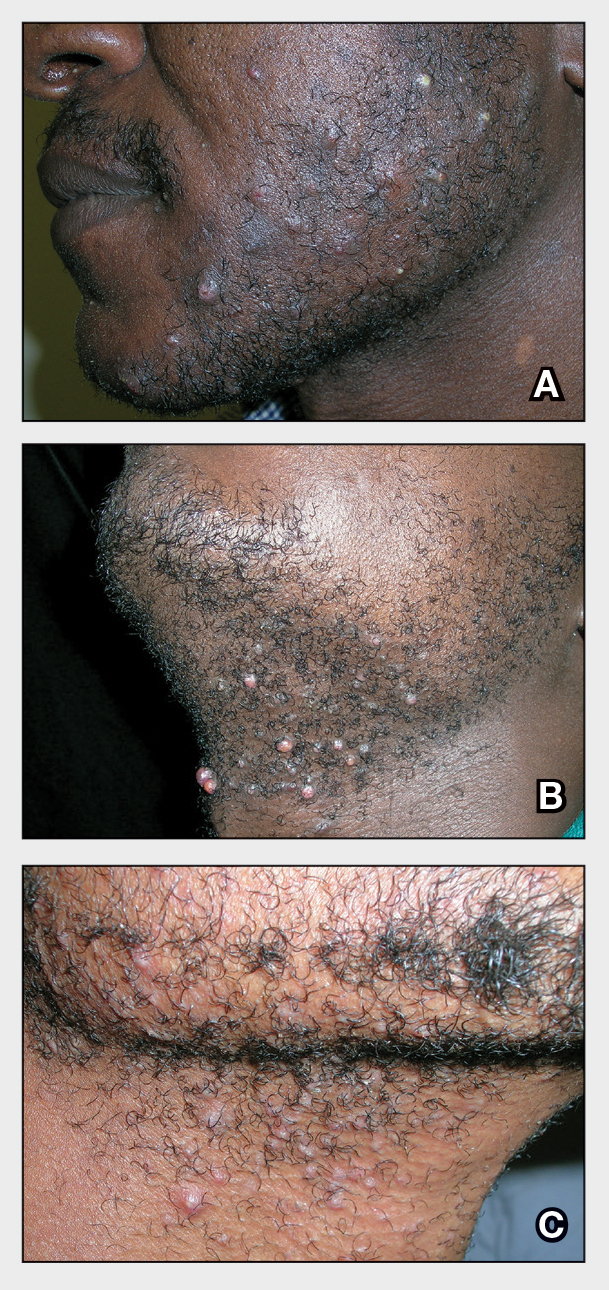

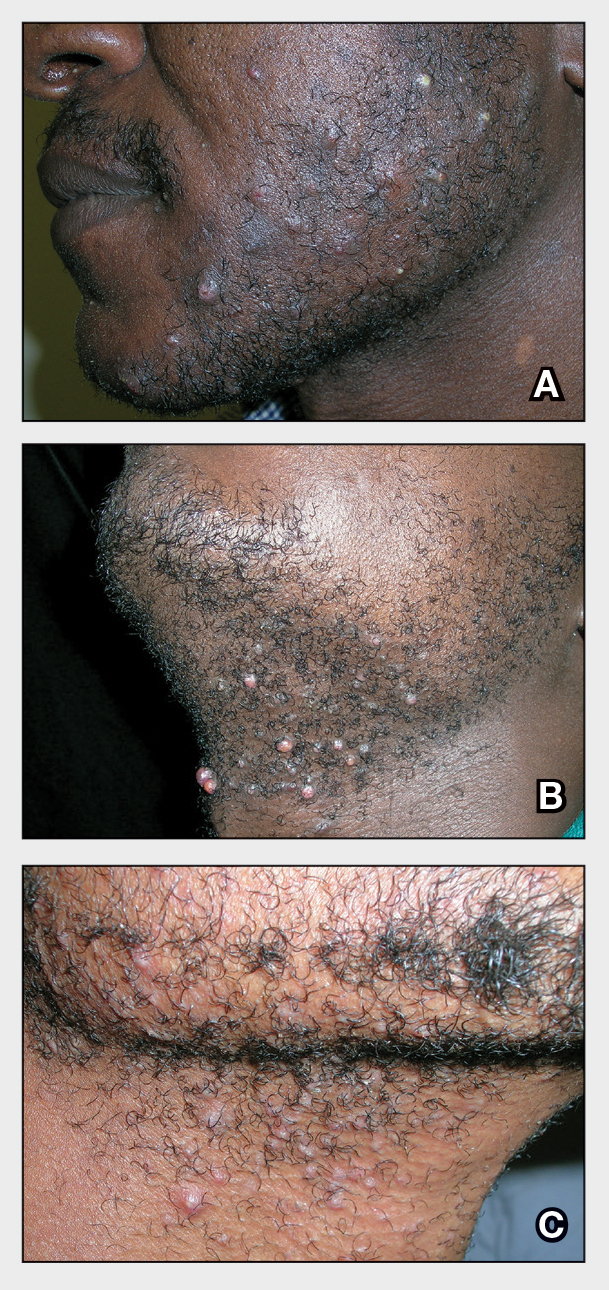

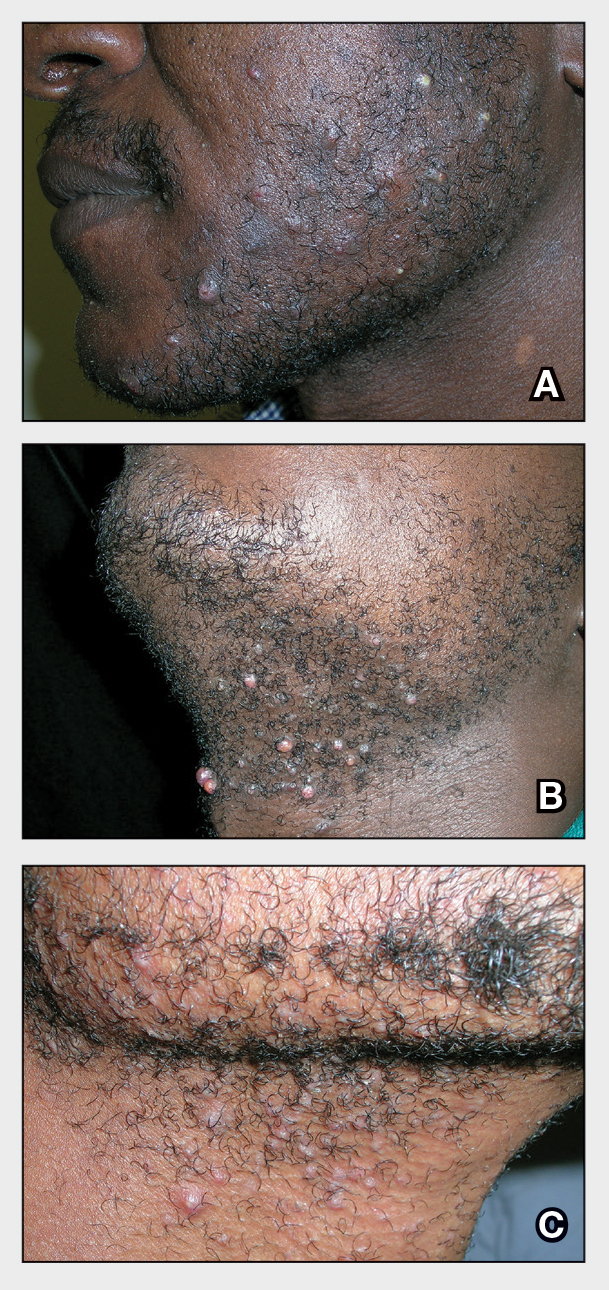

- A. Pustules, erythematous to violaceous nodules, and hyperpigmented patches on the lower cheek and chin.

- B. Brown papules, pink keloidal papules and nodules, pustules, and hyperpigmented papules on the mandibular area and neck.

- C. Coarse hairs, pustules, and pink papules on the mandibular area and neck.

Pseudofolliculitis barbae (PFB), also known as razor bumps, is a common inflammatory condition characterized by papules and pustules that typically appear in the beard and cheek regions. It occurs when shaved hair regrows and penetrates the skin, leading to irritation and inflammation. While anyone who shaves can develop PFB, it is more prevalent and severe in individuals with naturally tightly coiled, coarse-textured hair.1,2 Pseudofolliculitis barbae is common in individuals who shave frequently due to personal choice or profession, such as members of the US military3,4 and firefighters, who are required to remain clean shaven for safety (eg, ensuring proper fit of a respirator mask).5 Early diagnosis and treatment of PFB are essential to prevent long-term complications such as scarring or hyperpigmentation, which may be more severe in those with darker skin tones.

Epidemiology

Pseudofolliculitis barbae is most common in Black men, affecting 45% to 83% of men of African ancestry.1,2 This condition also can affect individuals of various ethnicities with coarse or curly hair. The spiral shape of the hair increases the likelihood that it will regrow into the skin after shaving.6 Women with hirsutism who shave also can develop PFB.

Key Clinical Features

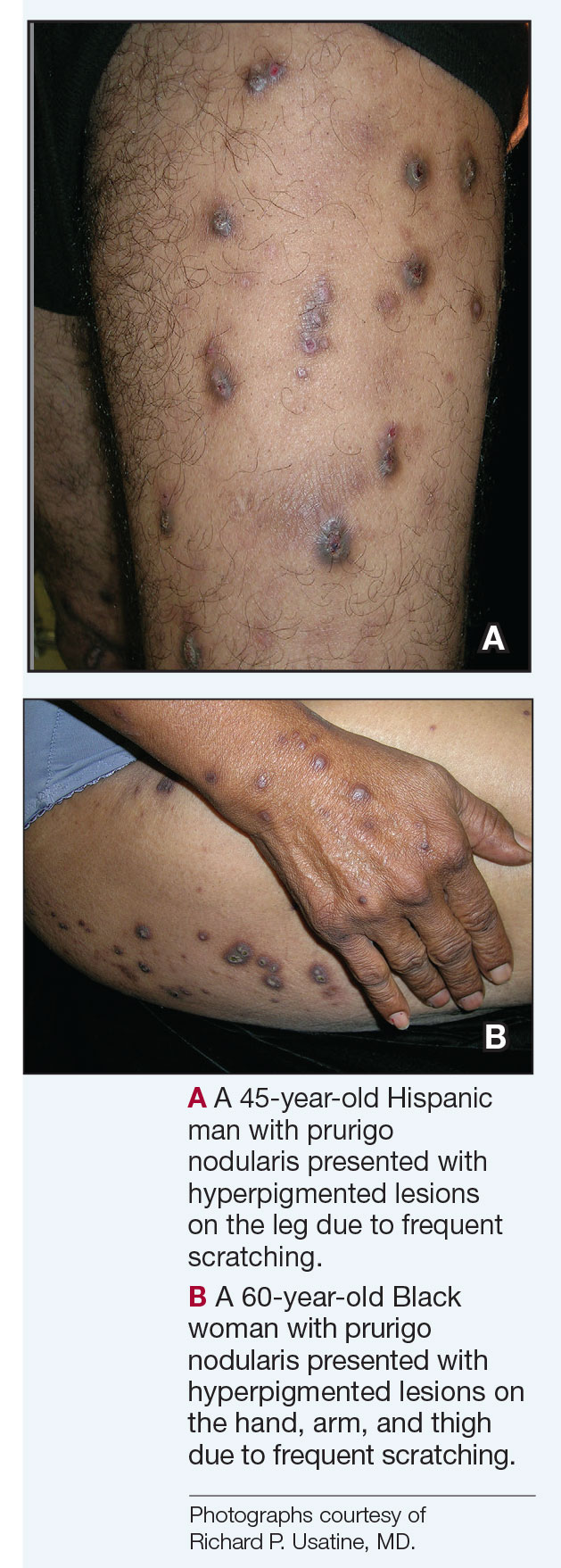

The papules and pustules seen in PFB may be flesh colored, erythematous, hyperpigmented, brown, or violaceous. Erythema may be less pronounced in darker vs lighter skin tones. Persistent and severe postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may occur, and hypertrophic or keloidal scars may develop in affected areas. Dermoscopy may reveal extrafollicular hair penetration as well as follicular or perifollicular pustules accompanied by hyperkeratosis.

Worth Noting

The most effective management for PFB is to discontinue shaving.1 If shaving is desired or necessary, it is recommended that patients apply lukewarm water to the affected area followed by a generous amount of shaving foam or gel to create a protective antifriction layer that allows the razor to glide more smoothly over the skin and reduces subsequent irritation.2 Using the right razor technology also may help alleviate symptoms. Research has shown that multiblade razors used in conjunction with preshave hair hydration and postshave moisturization do not worsen PFB.2 A recent study found that multiblade razor technology paired with use of a shave foam or gel actually improved skin appearance in patients with PFB.7

It is important to direct patients to shave in the direction of hair growth; however, this may not be possible for individuals with curly or coarse hair, as the hair may grow in many directions.8,9 Patients also should avoid pulling the skin taut while shaving, as doing so allows the hair to be clipped below the surface, where it can repenetrate the skin and cause further irritation. As an alternative to shaving with a razor, patients can use hair clippers to trim beard hair, which leaves behind stubble and interrupts the cycle of retracted hairs under the skin. Nd:YAG laser therapy has demonstrated efficacy in reduction of PFB papules and pustules.9-12 Greater mean improvement in inflammatory papules and reduction in hair density was noted in participants who received Nd:YAG laser plus eflornithine compared with those who received the laser or eflornithine alone.11 Patients should not pluck or dig into the skin to remove any ingrown hairs. If a tweezer is used, the patient should gently lift the tip of the ingrown hair with the tweezer to dislodge it from the skin and prevent plucking out the hair completely.

To help manage inflammation after shaving, topical treatments such as benzoyl peroxide 5%/clindamycin 1% gel can be used.3,13 A low-potency steroid such as topical hydrocortisone 2.5% applied once or twice daily for up to 2 to 3 days may be helpful.1,14 Adjunctive treatments including keratolytics (eg, topical retinoids, hydroxy acids) reduce perifollicular hyperkeratosis.14,15 Agents containing alpha hydroxy acids (eg, glycolic acid) also can decrease the curvature of the hair itself by reducing the sulfhydryl bonds.6 If secondary bacterial infections occur, oral antibiotics (eg, doxycycline) may be necessary.

Health Disparity Highlight

Individuals with darker skin tones are at higher risk for PFB and associated complications. Limited access to dermatology services may further exacerbate these challenges. Individuals with PFB may not seek medical treatment until the condition becomes severe. Clinicians also may underestimate the severity of PFB—particularly in those with darker skin tones—based on erythema alone because it may be less pronounced in darker vs lighter skin tones.16

While permanent hair reduction with laser therapy is a treatment option for PFB, it may be inaccessible to some patients because it can be expensive and is coded as a cosmetic procedure. Additionally, patients may not have access to specialists who are experienced in performing the procedure in those with darker skin tones.9 Some patients also may not want to permanently reduce the amount of hair that grows in the beard area for personal or religious reasons.17

Pseudofolliculitis barbae also has been linked to professional disparities. One study found that members of the US Air Force who had medical shaving waivers experienced longer times to promotion than those with no waiver.18 Delays in promotion may be linked to perceptions of unprofessionalism, exclusion from high-profile duties, and concerns about career progression. While this delay was similar for individuals of all races, the majority of those in the waiver group were Black/African American. In 2021, 4 Black firefighters with PFB were unsuccessful in their bid to get a medical accommodation regarding a New York City Fire Department policy requiring them to be clean shaven where the oxygen mask seals against the skin.5 More research is needed on mask safety and efficiency relative to the length of facial hair. Accommodations or tailored masks for facial hair conditions also are necessary so individuals with PFB can meet job requirements while managing their condition.

- Alexis A, Heath CR, Halder RM. Folliculitis keloidalis nuchae and pseudofolliculitis barbae: are prevention and effective treatment within reach? em>Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:183-191.

- Gray J, McMichael AJ. Pseudofolliculitis barbae: understanding the condition and the role of facial grooming. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2016;38 (suppl 1):24-27.

- Tshudy MT, Cho S. Pseudofolliculitis barbae in the U.S. military, a review. Mil Med. 2021;186:E52-E57.

- Jung I, Lannan FM, Weiss A, et al. Treatment and current policies on pseudofolliculitis barbae in the US military. Cutis. 2023;112:299-302.

- Jiang YR. Reasonable accommodation and disparate impact: clean shave policy discrimination in today’s workplace. J Law Med Ethics. 2023;51:185-195.

- Taylor SC, Barbosa V, Burgess C, et al. Hair and scalp disorders in adult and pediatric patients with skin of color. Cutis. 2017;100:31-35.

- Moran E, McMichael A, De Souza B, et al. New razor technology improves appearance and quality of life in men with pseudofolliculitis barbae. Cutis. 2022;110:329-334.

- Maurer M, Rietzler M, Burghardt R, et al. The male beard hair and facial skin—challenges for shaving. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2016;38 (suppl 1):3-9.

- Ross EV. How would you treat this patient with lasers & EBDs? casebased panel. Presented at: Skin of Color Update; September 13, 2024; New York, NY.

- Ross EV, Cooke LM, Timko AL, et al. Treatment of pseudofolliculitis barbae in skin types IV, V, and VI with a long-pulsed neodymium:yttrium aluminum garnet laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:263-270.

- Shokeir H, Samy N, Taymour M. Pseudofolliculitis barbae treatment: efficacy of topical eflornithine, long-pulsed Nd-YAG laser versus their combination. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:3517-3525.

- Amer A, Elsayed A, Gharib K. Evaluation of efficacy and safety of chemical peeling and long-pulse Nd:YAG laser in treatment of pseudofolliculitis barbae. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14859.

- Cook-Bolden FE, Barba A, Halder R, et al. Twice-daily applications of benzoyl peroxide 5%/clindamycin 1% gel versus vehicle in the treatment of pseudofolliculitis barbae. Cutis. 2004;73(6 suppl):18-24.

- Nussbaum D, Friedman A. Pseudofolliculitis barbae: a review of current treatment options. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:246-250.

- Quarles FN, Brody H, Johnson BA, et al. Pseudofolliculitis barbae. Dermatol Ther. 2007;20:133-136.

- McMichael AJ, Frey C. Challenging the tools used to measure cutaneous lupus severity in patients of all skin types. JAMA Dermatol. 2025;161:9-10.

- Okonkwo E, Neal B, Harper HL. Pseudofolliculitis barbae in the military and the need for social awareness. Mil Med. 2021;186:143-144.

- Ritchie S, Park J, Banta J, et al. Shaving waivers in the United States Air Force and their impact on promotions of Black/African-American members. Mil Med. 2023;188:E242-E247.

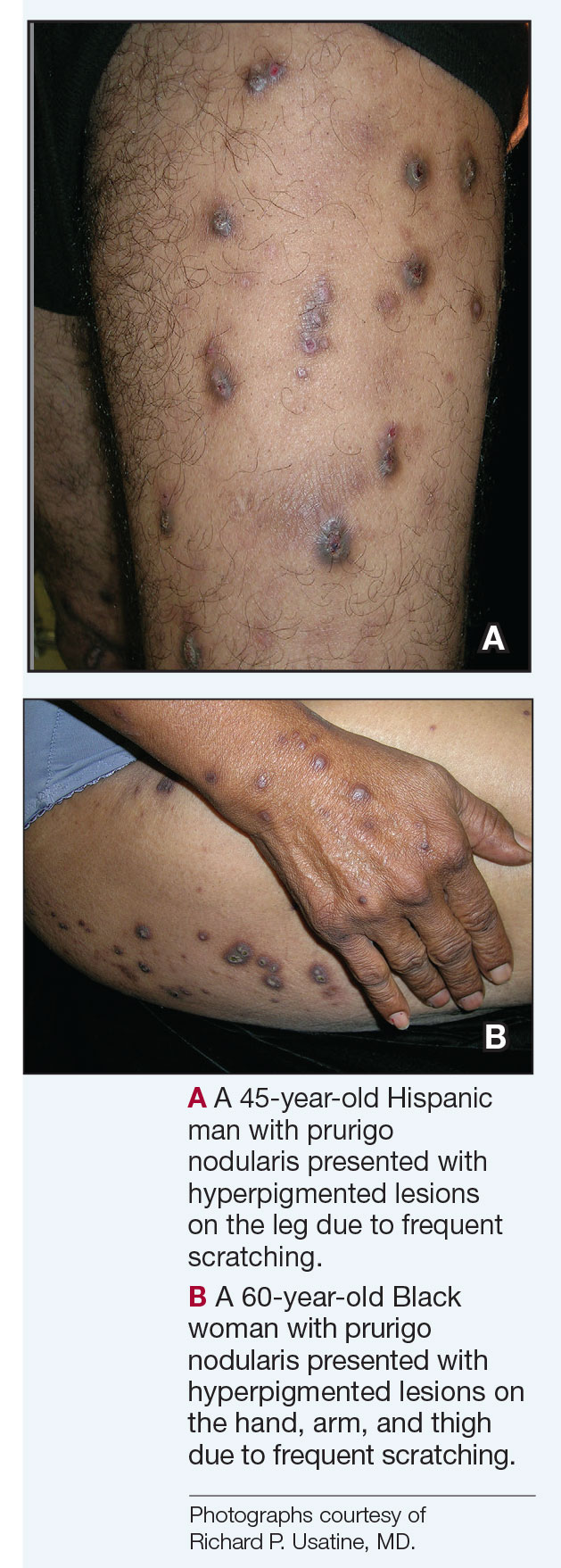

THE COMPARISON

- A. Pustules, erythematous to violaceous nodules, and hyperpigmented patches on the lower cheek and chin.

- B. Brown papules, pink keloidal papules and nodules, pustules, and hyperpigmented papules on the mandibular area and neck.

- C. Coarse hairs, pustules, and pink papules on the mandibular area and neck.

Pseudofolliculitis barbae (PFB), also known as razor bumps, is a common inflammatory condition characterized by papules and pustules that typically appear in the beard and cheek regions. It occurs when shaved hair regrows and penetrates the skin, leading to irritation and inflammation. While anyone who shaves can develop PFB, it is more prevalent and severe in individuals with naturally tightly coiled, coarse-textured hair.1,2 Pseudofolliculitis barbae is common in individuals who shave frequently due to personal choice or profession, such as members of the US military3,4 and firefighters, who are required to remain clean shaven for safety (eg, ensuring proper fit of a respirator mask).5 Early diagnosis and treatment of PFB are essential to prevent long-term complications such as scarring or hyperpigmentation, which may be more severe in those with darker skin tones.

Epidemiology

Pseudofolliculitis barbae is most common in Black men, affecting 45% to 83% of men of African ancestry.1,2 This condition also can affect individuals of various ethnicities with coarse or curly hair. The spiral shape of the hair increases the likelihood that it will regrow into the skin after shaving.6 Women with hirsutism who shave also can develop PFB.

Key Clinical Features

The papules and pustules seen in PFB may be flesh colored, erythematous, hyperpigmented, brown, or violaceous. Erythema may be less pronounced in darker vs lighter skin tones. Persistent and severe postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may occur, and hypertrophic or keloidal scars may develop in affected areas. Dermoscopy may reveal extrafollicular hair penetration as well as follicular or perifollicular pustules accompanied by hyperkeratosis.

Worth Noting

The most effective management for PFB is to discontinue shaving.1 If shaving is desired or necessary, it is recommended that patients apply lukewarm water to the affected area followed by a generous amount of shaving foam or gel to create a protective antifriction layer that allows the razor to glide more smoothly over the skin and reduces subsequent irritation.2 Using the right razor technology also may help alleviate symptoms. Research has shown that multiblade razors used in conjunction with preshave hair hydration and postshave moisturization do not worsen PFB.2 A recent study found that multiblade razor technology paired with use of a shave foam or gel actually improved skin appearance in patients with PFB.7

It is important to direct patients to shave in the direction of hair growth; however, this may not be possible for individuals with curly or coarse hair, as the hair may grow in many directions.8,9 Patients also should avoid pulling the skin taut while shaving, as doing so allows the hair to be clipped below the surface, where it can repenetrate the skin and cause further irritation. As an alternative to shaving with a razor, patients can use hair clippers to trim beard hair, which leaves behind stubble and interrupts the cycle of retracted hairs under the skin. Nd:YAG laser therapy has demonstrated efficacy in reduction of PFB papules and pustules.9-12 Greater mean improvement in inflammatory papules and reduction in hair density was noted in participants who received Nd:YAG laser plus eflornithine compared with those who received the laser or eflornithine alone.11 Patients should not pluck or dig into the skin to remove any ingrown hairs. If a tweezer is used, the patient should gently lift the tip of the ingrown hair with the tweezer to dislodge it from the skin and prevent plucking out the hair completely.

To help manage inflammation after shaving, topical treatments such as benzoyl peroxide 5%/clindamycin 1% gel can be used.3,13 A low-potency steroid such as topical hydrocortisone 2.5% applied once or twice daily for up to 2 to 3 days may be helpful.1,14 Adjunctive treatments including keratolytics (eg, topical retinoids, hydroxy acids) reduce perifollicular hyperkeratosis.14,15 Agents containing alpha hydroxy acids (eg, glycolic acid) also can decrease the curvature of the hair itself by reducing the sulfhydryl bonds.6 If secondary bacterial infections occur, oral antibiotics (eg, doxycycline) may be necessary.

Health Disparity Highlight

Individuals with darker skin tones are at higher risk for PFB and associated complications. Limited access to dermatology services may further exacerbate these challenges. Individuals with PFB may not seek medical treatment until the condition becomes severe. Clinicians also may underestimate the severity of PFB—particularly in those with darker skin tones—based on erythema alone because it may be less pronounced in darker vs lighter skin tones.16

While permanent hair reduction with laser therapy is a treatment option for PFB, it may be inaccessible to some patients because it can be expensive and is coded as a cosmetic procedure. Additionally, patients may not have access to specialists who are experienced in performing the procedure in those with darker skin tones.9 Some patients also may not want to permanently reduce the amount of hair that grows in the beard area for personal or religious reasons.17

Pseudofolliculitis barbae also has been linked to professional disparities. One study found that members of the US Air Force who had medical shaving waivers experienced longer times to promotion than those with no waiver.18 Delays in promotion may be linked to perceptions of unprofessionalism, exclusion from high-profile duties, and concerns about career progression. While this delay was similar for individuals of all races, the majority of those in the waiver group were Black/African American. In 2021, 4 Black firefighters with PFB were unsuccessful in their bid to get a medical accommodation regarding a New York City Fire Department policy requiring them to be clean shaven where the oxygen mask seals against the skin.5 More research is needed on mask safety and efficiency relative to the length of facial hair. Accommodations or tailored masks for facial hair conditions also are necessary so individuals with PFB can meet job requirements while managing their condition.

THE COMPARISON

- A. Pustules, erythematous to violaceous nodules, and hyperpigmented patches on the lower cheek and chin.

- B. Brown papules, pink keloidal papules and nodules, pustules, and hyperpigmented papules on the mandibular area and neck.

- C. Coarse hairs, pustules, and pink papules on the mandibular area and neck.

Pseudofolliculitis barbae (PFB), also known as razor bumps, is a common inflammatory condition characterized by papules and pustules that typically appear in the beard and cheek regions. It occurs when shaved hair regrows and penetrates the skin, leading to irritation and inflammation. While anyone who shaves can develop PFB, it is more prevalent and severe in individuals with naturally tightly coiled, coarse-textured hair.1,2 Pseudofolliculitis barbae is common in individuals who shave frequently due to personal choice or profession, such as members of the US military3,4 and firefighters, who are required to remain clean shaven for safety (eg, ensuring proper fit of a respirator mask).5 Early diagnosis and treatment of PFB are essential to prevent long-term complications such as scarring or hyperpigmentation, which may be more severe in those with darker skin tones.

Epidemiology

Pseudofolliculitis barbae is most common in Black men, affecting 45% to 83% of men of African ancestry.1,2 This condition also can affect individuals of various ethnicities with coarse or curly hair. The spiral shape of the hair increases the likelihood that it will regrow into the skin after shaving.6 Women with hirsutism who shave also can develop PFB.

Key Clinical Features

The papules and pustules seen in PFB may be flesh colored, erythematous, hyperpigmented, brown, or violaceous. Erythema may be less pronounced in darker vs lighter skin tones. Persistent and severe postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may occur, and hypertrophic or keloidal scars may develop in affected areas. Dermoscopy may reveal extrafollicular hair penetration as well as follicular or perifollicular pustules accompanied by hyperkeratosis.

Worth Noting

The most effective management for PFB is to discontinue shaving.1 If shaving is desired or necessary, it is recommended that patients apply lukewarm water to the affected area followed by a generous amount of shaving foam or gel to create a protective antifriction layer that allows the razor to glide more smoothly over the skin and reduces subsequent irritation.2 Using the right razor technology also may help alleviate symptoms. Research has shown that multiblade razors used in conjunction with preshave hair hydration and postshave moisturization do not worsen PFB.2 A recent study found that multiblade razor technology paired with use of a shave foam or gel actually improved skin appearance in patients with PFB.7

It is important to direct patients to shave in the direction of hair growth; however, this may not be possible for individuals with curly or coarse hair, as the hair may grow in many directions.8,9 Patients also should avoid pulling the skin taut while shaving, as doing so allows the hair to be clipped below the surface, where it can repenetrate the skin and cause further irritation. As an alternative to shaving with a razor, patients can use hair clippers to trim beard hair, which leaves behind stubble and interrupts the cycle of retracted hairs under the skin. Nd:YAG laser therapy has demonstrated efficacy in reduction of PFB papules and pustules.9-12 Greater mean improvement in inflammatory papules and reduction in hair density was noted in participants who received Nd:YAG laser plus eflornithine compared with those who received the laser or eflornithine alone.11 Patients should not pluck or dig into the skin to remove any ingrown hairs. If a tweezer is used, the patient should gently lift the tip of the ingrown hair with the tweezer to dislodge it from the skin and prevent plucking out the hair completely.

To help manage inflammation after shaving, topical treatments such as benzoyl peroxide 5%/clindamycin 1% gel can be used.3,13 A low-potency steroid such as topical hydrocortisone 2.5% applied once or twice daily for up to 2 to 3 days may be helpful.1,14 Adjunctive treatments including keratolytics (eg, topical retinoids, hydroxy acids) reduce perifollicular hyperkeratosis.14,15 Agents containing alpha hydroxy acids (eg, glycolic acid) also can decrease the curvature of the hair itself by reducing the sulfhydryl bonds.6 If secondary bacterial infections occur, oral antibiotics (eg, doxycycline) may be necessary.

Health Disparity Highlight

Individuals with darker skin tones are at higher risk for PFB and associated complications. Limited access to dermatology services may further exacerbate these challenges. Individuals with PFB may not seek medical treatment until the condition becomes severe. Clinicians also may underestimate the severity of PFB—particularly in those with darker skin tones—based on erythema alone because it may be less pronounced in darker vs lighter skin tones.16

While permanent hair reduction with laser therapy is a treatment option for PFB, it may be inaccessible to some patients because it can be expensive and is coded as a cosmetic procedure. Additionally, patients may not have access to specialists who are experienced in performing the procedure in those with darker skin tones.9 Some patients also may not want to permanently reduce the amount of hair that grows in the beard area for personal or religious reasons.17

Pseudofolliculitis barbae also has been linked to professional disparities. One study found that members of the US Air Force who had medical shaving waivers experienced longer times to promotion than those with no waiver.18 Delays in promotion may be linked to perceptions of unprofessionalism, exclusion from high-profile duties, and concerns about career progression. While this delay was similar for individuals of all races, the majority of those in the waiver group were Black/African American. In 2021, 4 Black firefighters with PFB were unsuccessful in their bid to get a medical accommodation regarding a New York City Fire Department policy requiring them to be clean shaven where the oxygen mask seals against the skin.5 More research is needed on mask safety and efficiency relative to the length of facial hair. Accommodations or tailored masks for facial hair conditions also are necessary so individuals with PFB can meet job requirements while managing their condition.

- Alexis A, Heath CR, Halder RM. Folliculitis keloidalis nuchae and pseudofolliculitis barbae: are prevention and effective treatment within reach? em>Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:183-191.

- Gray J, McMichael AJ. Pseudofolliculitis barbae: understanding the condition and the role of facial grooming. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2016;38 (suppl 1):24-27.

- Tshudy MT, Cho S. Pseudofolliculitis barbae in the U.S. military, a review. Mil Med. 2021;186:E52-E57.

- Jung I, Lannan FM, Weiss A, et al. Treatment and current policies on pseudofolliculitis barbae in the US military. Cutis. 2023;112:299-302.

- Jiang YR. Reasonable accommodation and disparate impact: clean shave policy discrimination in today’s workplace. J Law Med Ethics. 2023;51:185-195.

- Taylor SC, Barbosa V, Burgess C, et al. Hair and scalp disorders in adult and pediatric patients with skin of color. Cutis. 2017;100:31-35.

- Moran E, McMichael A, De Souza B, et al. New razor technology improves appearance and quality of life in men with pseudofolliculitis barbae. Cutis. 2022;110:329-334.

- Maurer M, Rietzler M, Burghardt R, et al. The male beard hair and facial skin—challenges for shaving. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2016;38 (suppl 1):3-9.

- Ross EV. How would you treat this patient with lasers & EBDs? casebased panel. Presented at: Skin of Color Update; September 13, 2024; New York, NY.

- Ross EV, Cooke LM, Timko AL, et al. Treatment of pseudofolliculitis barbae in skin types IV, V, and VI with a long-pulsed neodymium:yttrium aluminum garnet laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:263-270.

- Shokeir H, Samy N, Taymour M. Pseudofolliculitis barbae treatment: efficacy of topical eflornithine, long-pulsed Nd-YAG laser versus their combination. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:3517-3525.

- Amer A, Elsayed A, Gharib K. Evaluation of efficacy and safety of chemical peeling and long-pulse Nd:YAG laser in treatment of pseudofolliculitis barbae. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14859.

- Cook-Bolden FE, Barba A, Halder R, et al. Twice-daily applications of benzoyl peroxide 5%/clindamycin 1% gel versus vehicle in the treatment of pseudofolliculitis barbae. Cutis. 2004;73(6 suppl):18-24.

- Nussbaum D, Friedman A. Pseudofolliculitis barbae: a review of current treatment options. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:246-250.

- Quarles FN, Brody H, Johnson BA, et al. Pseudofolliculitis barbae. Dermatol Ther. 2007;20:133-136.

- McMichael AJ, Frey C. Challenging the tools used to measure cutaneous lupus severity in patients of all skin types. JAMA Dermatol. 2025;161:9-10.

- Okonkwo E, Neal B, Harper HL. Pseudofolliculitis barbae in the military and the need for social awareness. Mil Med. 2021;186:143-144.

- Ritchie S, Park J, Banta J, et al. Shaving waivers in the United States Air Force and their impact on promotions of Black/African-American members. Mil Med. 2023;188:E242-E247.

- Alexis A, Heath CR, Halder RM. Folliculitis keloidalis nuchae and pseudofolliculitis barbae: are prevention and effective treatment within reach? em>Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:183-191.

- Gray J, McMichael AJ. Pseudofolliculitis barbae: understanding the condition and the role of facial grooming. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2016;38 (suppl 1):24-27.

- Tshudy MT, Cho S. Pseudofolliculitis barbae in the U.S. military, a review. Mil Med. 2021;186:E52-E57.

- Jung I, Lannan FM, Weiss A, et al. Treatment and current policies on pseudofolliculitis barbae in the US military. Cutis. 2023;112:299-302.

- Jiang YR. Reasonable accommodation and disparate impact: clean shave policy discrimination in today’s workplace. J Law Med Ethics. 2023;51:185-195.

- Taylor SC, Barbosa V, Burgess C, et al. Hair and scalp disorders in adult and pediatric patients with skin of color. Cutis. 2017;100:31-35.

- Moran E, McMichael A, De Souza B, et al. New razor technology improves appearance and quality of life in men with pseudofolliculitis barbae. Cutis. 2022;110:329-334.

- Maurer M, Rietzler M, Burghardt R, et al. The male beard hair and facial skin—challenges for shaving. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2016;38 (suppl 1):3-9.

- Ross EV. How would you treat this patient with lasers & EBDs? casebased panel. Presented at: Skin of Color Update; September 13, 2024; New York, NY.

- Ross EV, Cooke LM, Timko AL, et al. Treatment of pseudofolliculitis barbae in skin types IV, V, and VI with a long-pulsed neodymium:yttrium aluminum garnet laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:263-270.

- Shokeir H, Samy N, Taymour M. Pseudofolliculitis barbae treatment: efficacy of topical eflornithine, long-pulsed Nd-YAG laser versus their combination. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:3517-3525.

- Amer A, Elsayed A, Gharib K. Evaluation of efficacy and safety of chemical peeling and long-pulse Nd:YAG laser in treatment of pseudofolliculitis barbae. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14859.

- Cook-Bolden FE, Barba A, Halder R, et al. Twice-daily applications of benzoyl peroxide 5%/clindamycin 1% gel versus vehicle in the treatment of pseudofolliculitis barbae. Cutis. 2004;73(6 suppl):18-24.

- Nussbaum D, Friedman A. Pseudofolliculitis barbae: a review of current treatment options. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:246-250.

- Quarles FN, Brody H, Johnson BA, et al. Pseudofolliculitis barbae. Dermatol Ther. 2007;20:133-136.

- McMichael AJ, Frey C. Challenging the tools used to measure cutaneous lupus severity in patients of all skin types. JAMA Dermatol. 2025;161:9-10.

- Okonkwo E, Neal B, Harper HL. Pseudofolliculitis barbae in the military and the need for social awareness. Mil Med. 2021;186:143-144.

- Ritchie S, Park J, Banta J, et al. Shaving waivers in the United States Air Force and their impact on promotions of Black/African-American members. Mil Med. 2023;188:E242-E247.

Beyond the Razor: Managing Pseudofolliculitis Barbae in Skin of Color

Beyond the Razor: Managing Pseudofolliculitis Barbae in Skin of Color

Key Features of Dermatosis Papulosa Nigra vs Seborrheic Keratosis

Key Features of Dermatosis Papulosa Nigra vs Seborrheic Keratosis

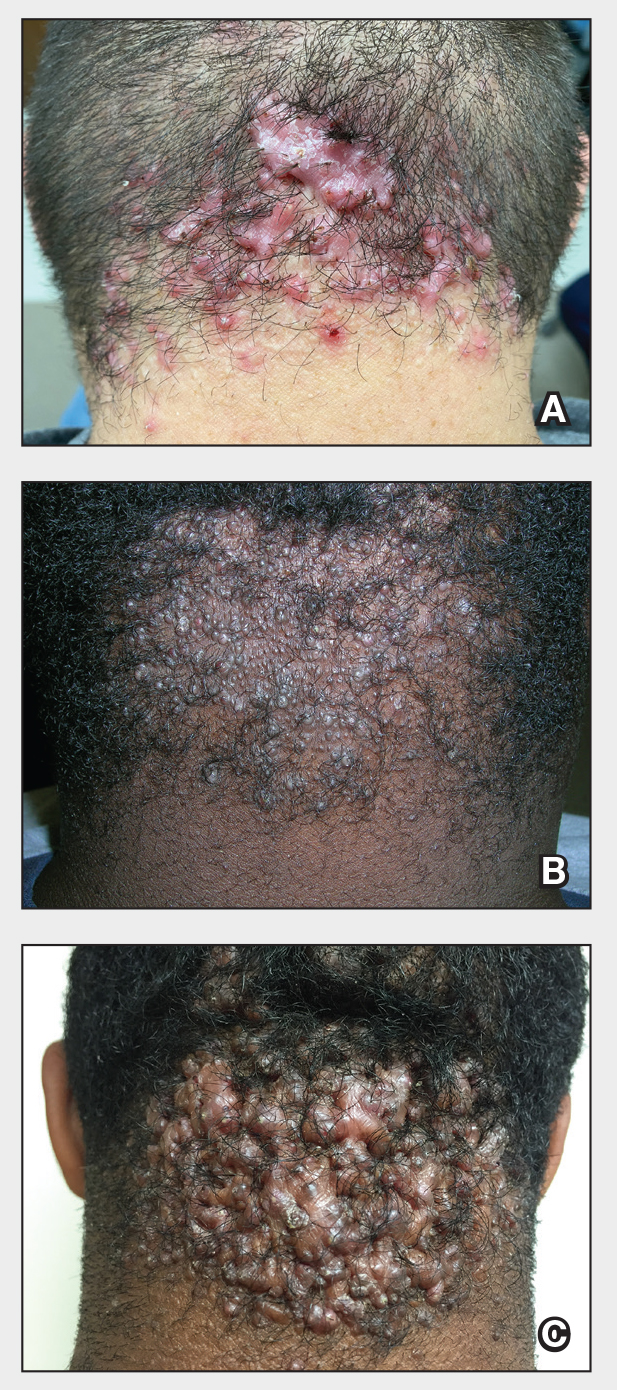

Dermatosis papulosa nigra (DPN), a subvariant of seborrheic keratosis (SK), is characterized by benign pigmented epidermal neoplasms that typically manifest on the face, neck, and trunk in individuals with darker skin tones (Figure).1,2 While DPN meets the diagnostic criteria for SK, certain characteristics can help distinguish these lesions from other SK types. Treatment of DPN in patients with skin of color requires caution, particularly regarding the use of abrasive methods as well as cryotherapy, which generally should be avoided.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The incidence of SKs increases with age.3,4 Although it can occur in patients of all skin tones, SK is more common in lighter skin tones, while DPN predominantly is diagnosed in darker skin types.1,4 The prevalence of DPN in Black patients ranges from 10% to 30%, and Black women are twice as likely to be diagnosed with DPN as men.2 One study reported a first-degree relative with DPN in 84% (42/50) of patients.5 The number and size of DPN papules increase with age.1

KEY CLINICAL FEATURES

Dermatosis papulosa nigra and SK have distinctive morphologies: DPN typically manifests as raised, round or filiform, sessile, brown to black, 1- to 5-mm papules. 2 Seborrheic keratoses tend to be larger with a “stuck on” appearance and manifest as well-demarcated, pink to black papules or plaques that can range in size from millimeters to a few centimeters. 3,4 In DPN, the lesions usually are asymptomatic but may be tender, pruritic, dry, or scaly and may become irritated.1,2 They develop symmetrically in sun-exposed areas, and the most common sites are the malar face, temporal region, neck, and trunk.1,2,6,7 Seborrheic keratoses can appear throughout the body, including in sun-exposed areas, but have varying textures (eg, greasy, waxy, verrucous).3,4

WORTH NOTING

Dermatosis papulosa nigra and SK can resemble each other histologically: DPN demonstrates a fibrous stroma, papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis, and acanthosis at the intraepidermal layer, which are diagnostic criteria for SK.2,4,8 However, other histologic features characteristic of SK that are not seen in DPN include pseudohorn cysts, spindle tumor cells, and basaloid cell nests.8

Dermoscopy can be useful in ruling out malignant skin cancers when evaluating pigmented lesions. The most common dermoscopic features of SK are cerebriform patterns such as fissures and ridges, comedolike openings, and pigmented fingerprintlike structures.3,4 To a lesser degree, milialike cysts, sharp demarcation, and hairpin-shaped vascular structures also may be present.4 The dermoscopic findings of DPN have not been well evaluated, but one study revealed that DPN had similar dermoscopic features to SK with some predominant features.6 Ridges and fissures were seen in 59% of patients diagnosed with DPN followed by comedolike openings seen in 27% of patients. The coexistence of a cerebriform pattern with comedolike openings was infrequent, and milialike cysts were rare.6

While DPN and SK are benign, patients often seek treatment for cosmetic reasons. Factors to consider when choosing a treatment modality include location of the lesions, the patient’s skin tone, and postprocedural outcomes (eg, depigmentation, wound healing). In general, treatments for SK include cryotherapy, electrodesiccation and curettage, and topical therapeutics such as hydrogen peroxide 40%, topical vitamin D3, and nitric-zinc 30%-50% solutions. 4,8 Well-established treatment options for DPN include electrodesiccation, laser therapies, scissor excision, and cryotherapy, but topical options such as tazarotene also have been reported.1,9 Of the treatments for DPN, electrodesiccation and laser therapy routinely are used.10

The efficacy of electrodessication and potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP) laser were assessed in a randomized, investigatorblinded split-face study.11 Both modalities received high improvement ratings, with the results favoring the KTP laser. The patients (most of whom were Black) reported that KTP laser was more effective but more painful than electrodessication (P =.002).11 In another randomized study, patients received 3 treatments—electrodessication, pulsed dye laser, and curettage—for select DPN papules.10 There was no difference in the degree of clearance, cosmetic outcome, or postinflammatory hyperpigmentation between the 3 modalities, but patients found the laser to be the most painful.

It is important to exercise caution when using abrasive methods (eg, laser therapy, electrodesiccation, curettage) in patients with darker skin tones because of the increased risk for postinflammatory pigment alteration.1,2,12 Adverse effects of treatment are a top concern in the management of DPN.5,13 While cryotherapy is a preferred treatment of SK in lighter skin tones, it generally is avoided for DPN in darker skin types because melanocyte destruction can lead to cosmetically unsatisfactory and easily visible depigmentation.9

To mitigate postprocedural adverse effects, proper aftercare can promote wound healing and minimize postinflammatory pigment alteration. In one split-face study of Black patients, 2 DPN papules were removed from each side of the face using fine-curved surgical scissors.14 Next, a petrolatum-based ointment and an antibiotic ointment with polymyxin B sulfate/bacitracin zinc was applied twice daily for 21 days to opposite sides of the face. Patients did not develop infection, tolerated both treatments well, and demonstrated improved general wound appearance according to investigator- rated clinical assessment.14 Other reported postprocedural approaches include using topical agents with ingredients shown to improve hyperpigmentation (eg, niacinamide, azelaic acid) as well as photoprotection.12

HEALTH DISPARITY HIGHLIGHT

While DPN is benign, it can have adverse psychosocial effects on patients. A study in Senegal revealed that 60% (19/30) of patients with DPN experienced anxiety related to their condition, while others noted that DPN hindered their social relationships.13 In one US study of 50 Black patients with DPN, there was a moderate effect on quality of life, and 36% (18/50) of patients had the lesions removed. However, of the treated patients, 67% (12/18) reported few—if any—symptoms prior to removal.5 Although treatment of DPN is widely considered a cosmetic procedure, therapeutic management can address— and may improve—mental health in patients with skin of color.1,5,13 Despite the high prevalence of DPN in patients with darker skin tones, data on treatment frequency and insurance coverage are not widely available, thus limiting our understanding of treatment accessibility and economic burden.

- Frazier WT, Proddutur S, Swope K. Common dermatologic conditions in skin of color. Am Fam Physician. 2023;107:26-34.

- Metin SA, Lee BW, Lambert WC, et al. Dermatosis papulosa nigra: a clinically and histopathologically distinct entity. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:491-496.

- Braun RP, Ludwig S, Marghoob AA. Differential diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis: clinical and dermoscopic features. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:835-842.

- Sun MD, Halpern AC. Advances in the etiology, detection, and clinical management of seborrheic keratoses. Dermatology. 2022;238:205-217.

- Uwakwe LN, De Souza B, Subash J, et al. Dermatosis papulosa nigra: a quality of life survey study. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13:17-19.

- Bhat RM, Patrao N, Monteiro R, et al. A clinical, dermoscopic, and histopathological study of dermatosis papulosa nigra (DPN)—an Indian perspective. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:957-960.

- Karampinis E, Georgopoulou KE, Kampra E, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic patterns of basal cell carcinoma and its mimickers in skin of color: a practical summary. Medicina (Kaunas). 2024;60:1386.

- Gorai S, Ahmad S, Raza SSM, et al. Update of pathophysiology and treatment options of seborrheic keratosis. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:E15934.

- Jain S, Caire H, Haas CJ. Management of dermatosis papulosa nigra: a systematic review. Int J Dermatol. Published online October 4, 2024.

- Garcia MS, Azari R, Eisen DB. Treatment of dermatosis papulosa nigra in 10 patients: a comparison trial of electrodesiccation, pulsed dye laser, and curettage. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1968-1972.

- Kundu RV, Joshi SS, Suh KY, et al. Comparison of electrodesiccation and potassium-titanyl-phosphate laser for treatment of dermatosis papulosa nigra. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1079-1083.

- Markiewicz E, Karaman-Jurukovska N, Mammone T, et al. Post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation in dark skin: molecular mechanism and skincare implications. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2022;15:2555-2565.

- Niang SO, Kane A, Diallo M, et al. Dermatosis papulosa nigra in Dakar, Senegal. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46(suppl 1):45-47.

- Taylor SC, Averyhart AN, Heath CR. Postprocedural wound-healing efficacy following removal of dermatosis papulosa nigra lesions in an African American population: a comparison of a skin protectant ointment and a topical antibiotic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(suppl 3):S30-S35.

Dermatosis papulosa nigra (DPN), a subvariant of seborrheic keratosis (SK), is characterized by benign pigmented epidermal neoplasms that typically manifest on the face, neck, and trunk in individuals with darker skin tones (Figure).1,2 While DPN meets the diagnostic criteria for SK, certain characteristics can help distinguish these lesions from other SK types. Treatment of DPN in patients with skin of color requires caution, particularly regarding the use of abrasive methods as well as cryotherapy, which generally should be avoided.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The incidence of SKs increases with age.3,4 Although it can occur in patients of all skin tones, SK is more common in lighter skin tones, while DPN predominantly is diagnosed in darker skin types.1,4 The prevalence of DPN in Black patients ranges from 10% to 30%, and Black women are twice as likely to be diagnosed with DPN as men.2 One study reported a first-degree relative with DPN in 84% (42/50) of patients.5 The number and size of DPN papules increase with age.1

KEY CLINICAL FEATURES

Dermatosis papulosa nigra and SK have distinctive morphologies: DPN typically manifests as raised, round or filiform, sessile, brown to black, 1- to 5-mm papules. 2 Seborrheic keratoses tend to be larger with a “stuck on” appearance and manifest as well-demarcated, pink to black papules or plaques that can range in size from millimeters to a few centimeters. 3,4 In DPN, the lesions usually are asymptomatic but may be tender, pruritic, dry, or scaly and may become irritated.1,2 They develop symmetrically in sun-exposed areas, and the most common sites are the malar face, temporal region, neck, and trunk.1,2,6,7 Seborrheic keratoses can appear throughout the body, including in sun-exposed areas, but have varying textures (eg, greasy, waxy, verrucous).3,4

WORTH NOTING

Dermatosis papulosa nigra and SK can resemble each other histologically: DPN demonstrates a fibrous stroma, papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis, and acanthosis at the intraepidermal layer, which are diagnostic criteria for SK.2,4,8 However, other histologic features characteristic of SK that are not seen in DPN include pseudohorn cysts, spindle tumor cells, and basaloid cell nests.8

Dermoscopy can be useful in ruling out malignant skin cancers when evaluating pigmented lesions. The most common dermoscopic features of SK are cerebriform patterns such as fissures and ridges, comedolike openings, and pigmented fingerprintlike structures.3,4 To a lesser degree, milialike cysts, sharp demarcation, and hairpin-shaped vascular structures also may be present.4 The dermoscopic findings of DPN have not been well evaluated, but one study revealed that DPN had similar dermoscopic features to SK with some predominant features.6 Ridges and fissures were seen in 59% of patients diagnosed with DPN followed by comedolike openings seen in 27% of patients. The coexistence of a cerebriform pattern with comedolike openings was infrequent, and milialike cysts were rare.6

While DPN and SK are benign, patients often seek treatment for cosmetic reasons. Factors to consider when choosing a treatment modality include location of the lesions, the patient’s skin tone, and postprocedural outcomes (eg, depigmentation, wound healing). In general, treatments for SK include cryotherapy, electrodesiccation and curettage, and topical therapeutics such as hydrogen peroxide 40%, topical vitamin D3, and nitric-zinc 30%-50% solutions. 4,8 Well-established treatment options for DPN include electrodesiccation, laser therapies, scissor excision, and cryotherapy, but topical options such as tazarotene also have been reported.1,9 Of the treatments for DPN, electrodesiccation and laser therapy routinely are used.10

The efficacy of electrodessication and potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP) laser were assessed in a randomized, investigatorblinded split-face study.11 Both modalities received high improvement ratings, with the results favoring the KTP laser. The patients (most of whom were Black) reported that KTP laser was more effective but more painful than electrodessication (P =.002).11 In another randomized study, patients received 3 treatments—electrodessication, pulsed dye laser, and curettage—for select DPN papules.10 There was no difference in the degree of clearance, cosmetic outcome, or postinflammatory hyperpigmentation between the 3 modalities, but patients found the laser to be the most painful.

It is important to exercise caution when using abrasive methods (eg, laser therapy, electrodesiccation, curettage) in patients with darker skin tones because of the increased risk for postinflammatory pigment alteration.1,2,12 Adverse effects of treatment are a top concern in the management of DPN.5,13 While cryotherapy is a preferred treatment of SK in lighter skin tones, it generally is avoided for DPN in darker skin types because melanocyte destruction can lead to cosmetically unsatisfactory and easily visible depigmentation.9

To mitigate postprocedural adverse effects, proper aftercare can promote wound healing and minimize postinflammatory pigment alteration. In one split-face study of Black patients, 2 DPN papules were removed from each side of the face using fine-curved surgical scissors.14 Next, a petrolatum-based ointment and an antibiotic ointment with polymyxin B sulfate/bacitracin zinc was applied twice daily for 21 days to opposite sides of the face. Patients did not develop infection, tolerated both treatments well, and demonstrated improved general wound appearance according to investigator- rated clinical assessment.14 Other reported postprocedural approaches include using topical agents with ingredients shown to improve hyperpigmentation (eg, niacinamide, azelaic acid) as well as photoprotection.12

HEALTH DISPARITY HIGHLIGHT

While DPN is benign, it can have adverse psychosocial effects on patients. A study in Senegal revealed that 60% (19/30) of patients with DPN experienced anxiety related to their condition, while others noted that DPN hindered their social relationships.13 In one US study of 50 Black patients with DPN, there was a moderate effect on quality of life, and 36% (18/50) of patients had the lesions removed. However, of the treated patients, 67% (12/18) reported few—if any—symptoms prior to removal.5 Although treatment of DPN is widely considered a cosmetic procedure, therapeutic management can address— and may improve—mental health in patients with skin of color.1,5,13 Despite the high prevalence of DPN in patients with darker skin tones, data on treatment frequency and insurance coverage are not widely available, thus limiting our understanding of treatment accessibility and economic burden.

Dermatosis papulosa nigra (DPN), a subvariant of seborrheic keratosis (SK), is characterized by benign pigmented epidermal neoplasms that typically manifest on the face, neck, and trunk in individuals with darker skin tones (Figure).1,2 While DPN meets the diagnostic criteria for SK, certain characteristics can help distinguish these lesions from other SK types. Treatment of DPN in patients with skin of color requires caution, particularly regarding the use of abrasive methods as well as cryotherapy, which generally should be avoided.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The incidence of SKs increases with age.3,4 Although it can occur in patients of all skin tones, SK is more common in lighter skin tones, while DPN predominantly is diagnosed in darker skin types.1,4 The prevalence of DPN in Black patients ranges from 10% to 30%, and Black women are twice as likely to be diagnosed with DPN as men.2 One study reported a first-degree relative with DPN in 84% (42/50) of patients.5 The number and size of DPN papules increase with age.1

KEY CLINICAL FEATURES

Dermatosis papulosa nigra and SK have distinctive morphologies: DPN typically manifests as raised, round or filiform, sessile, brown to black, 1- to 5-mm papules. 2 Seborrheic keratoses tend to be larger with a “stuck on” appearance and manifest as well-demarcated, pink to black papules or plaques that can range in size from millimeters to a few centimeters. 3,4 In DPN, the lesions usually are asymptomatic but may be tender, pruritic, dry, or scaly and may become irritated.1,2 They develop symmetrically in sun-exposed areas, and the most common sites are the malar face, temporal region, neck, and trunk.1,2,6,7 Seborrheic keratoses can appear throughout the body, including in sun-exposed areas, but have varying textures (eg, greasy, waxy, verrucous).3,4

WORTH NOTING

Dermatosis papulosa nigra and SK can resemble each other histologically: DPN demonstrates a fibrous stroma, papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis, and acanthosis at the intraepidermal layer, which are diagnostic criteria for SK.2,4,8 However, other histologic features characteristic of SK that are not seen in DPN include pseudohorn cysts, spindle tumor cells, and basaloid cell nests.8

Dermoscopy can be useful in ruling out malignant skin cancers when evaluating pigmented lesions. The most common dermoscopic features of SK are cerebriform patterns such as fissures and ridges, comedolike openings, and pigmented fingerprintlike structures.3,4 To a lesser degree, milialike cysts, sharp demarcation, and hairpin-shaped vascular structures also may be present.4 The dermoscopic findings of DPN have not been well evaluated, but one study revealed that DPN had similar dermoscopic features to SK with some predominant features.6 Ridges and fissures were seen in 59% of patients diagnosed with DPN followed by comedolike openings seen in 27% of patients. The coexistence of a cerebriform pattern with comedolike openings was infrequent, and milialike cysts were rare.6

While DPN and SK are benign, patients often seek treatment for cosmetic reasons. Factors to consider when choosing a treatment modality include location of the lesions, the patient’s skin tone, and postprocedural outcomes (eg, depigmentation, wound healing). In general, treatments for SK include cryotherapy, electrodesiccation and curettage, and topical therapeutics such as hydrogen peroxide 40%, topical vitamin D3, and nitric-zinc 30%-50% solutions. 4,8 Well-established treatment options for DPN include electrodesiccation, laser therapies, scissor excision, and cryotherapy, but topical options such as tazarotene also have been reported.1,9 Of the treatments for DPN, electrodesiccation and laser therapy routinely are used.10

The efficacy of electrodessication and potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP) laser were assessed in a randomized, investigatorblinded split-face study.11 Both modalities received high improvement ratings, with the results favoring the KTP laser. The patients (most of whom were Black) reported that KTP laser was more effective but more painful than electrodessication (P =.002).11 In another randomized study, patients received 3 treatments—electrodessication, pulsed dye laser, and curettage—for select DPN papules.10 There was no difference in the degree of clearance, cosmetic outcome, or postinflammatory hyperpigmentation between the 3 modalities, but patients found the laser to be the most painful.

It is important to exercise caution when using abrasive methods (eg, laser therapy, electrodesiccation, curettage) in patients with darker skin tones because of the increased risk for postinflammatory pigment alteration.1,2,12 Adverse effects of treatment are a top concern in the management of DPN.5,13 While cryotherapy is a preferred treatment of SK in lighter skin tones, it generally is avoided for DPN in darker skin types because melanocyte destruction can lead to cosmetically unsatisfactory and easily visible depigmentation.9

To mitigate postprocedural adverse effects, proper aftercare can promote wound healing and minimize postinflammatory pigment alteration. In one split-face study of Black patients, 2 DPN papules were removed from each side of the face using fine-curved surgical scissors.14 Next, a petrolatum-based ointment and an antibiotic ointment with polymyxin B sulfate/bacitracin zinc was applied twice daily for 21 days to opposite sides of the face. Patients did not develop infection, tolerated both treatments well, and demonstrated improved general wound appearance according to investigator- rated clinical assessment.14 Other reported postprocedural approaches include using topical agents with ingredients shown to improve hyperpigmentation (eg, niacinamide, azelaic acid) as well as photoprotection.12

HEALTH DISPARITY HIGHLIGHT

While DPN is benign, it can have adverse psychosocial effects on patients. A study in Senegal revealed that 60% (19/30) of patients with DPN experienced anxiety related to their condition, while others noted that DPN hindered their social relationships.13 In one US study of 50 Black patients with DPN, there was a moderate effect on quality of life, and 36% (18/50) of patients had the lesions removed. However, of the treated patients, 67% (12/18) reported few—if any—symptoms prior to removal.5 Although treatment of DPN is widely considered a cosmetic procedure, therapeutic management can address— and may improve—mental health in patients with skin of color.1,5,13 Despite the high prevalence of DPN in patients with darker skin tones, data on treatment frequency and insurance coverage are not widely available, thus limiting our understanding of treatment accessibility and economic burden.

- Frazier WT, Proddutur S, Swope K. Common dermatologic conditions in skin of color. Am Fam Physician. 2023;107:26-34.

- Metin SA, Lee BW, Lambert WC, et al. Dermatosis papulosa nigra: a clinically and histopathologically distinct entity. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:491-496.

- Braun RP, Ludwig S, Marghoob AA. Differential diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis: clinical and dermoscopic features. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:835-842.

- Sun MD, Halpern AC. Advances in the etiology, detection, and clinical management of seborrheic keratoses. Dermatology. 2022;238:205-217.

- Uwakwe LN, De Souza B, Subash J, et al. Dermatosis papulosa nigra: a quality of life survey study. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13:17-19.

- Bhat RM, Patrao N, Monteiro R, et al. A clinical, dermoscopic, and histopathological study of dermatosis papulosa nigra (DPN)—an Indian perspective. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:957-960.

- Karampinis E, Georgopoulou KE, Kampra E, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic patterns of basal cell carcinoma and its mimickers in skin of color: a practical summary. Medicina (Kaunas). 2024;60:1386.

- Gorai S, Ahmad S, Raza SSM, et al. Update of pathophysiology and treatment options of seborrheic keratosis. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:E15934.

- Jain S, Caire H, Haas CJ. Management of dermatosis papulosa nigra: a systematic review. Int J Dermatol. Published online October 4, 2024.

- Garcia MS, Azari R, Eisen DB. Treatment of dermatosis papulosa nigra in 10 patients: a comparison trial of electrodesiccation, pulsed dye laser, and curettage. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1968-1972.

- Kundu RV, Joshi SS, Suh KY, et al. Comparison of electrodesiccation and potassium-titanyl-phosphate laser for treatment of dermatosis papulosa nigra. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1079-1083.

- Markiewicz E, Karaman-Jurukovska N, Mammone T, et al. Post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation in dark skin: molecular mechanism and skincare implications. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2022;15:2555-2565.

- Niang SO, Kane A, Diallo M, et al. Dermatosis papulosa nigra in Dakar, Senegal. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46(suppl 1):45-47.

- Taylor SC, Averyhart AN, Heath CR. Postprocedural wound-healing efficacy following removal of dermatosis papulosa nigra lesions in an African American population: a comparison of a skin protectant ointment and a topical antibiotic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(suppl 3):S30-S35.

- Frazier WT, Proddutur S, Swope K. Common dermatologic conditions in skin of color. Am Fam Physician. 2023;107:26-34.

- Metin SA, Lee BW, Lambert WC, et al. Dermatosis papulosa nigra: a clinically and histopathologically distinct entity. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:491-496.

- Braun RP, Ludwig S, Marghoob AA. Differential diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis: clinical and dermoscopic features. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:835-842.

- Sun MD, Halpern AC. Advances in the etiology, detection, and clinical management of seborrheic keratoses. Dermatology. 2022;238:205-217.

- Uwakwe LN, De Souza B, Subash J, et al. Dermatosis papulosa nigra: a quality of life survey study. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13:17-19.

- Bhat RM, Patrao N, Monteiro R, et al. A clinical, dermoscopic, and histopathological study of dermatosis papulosa nigra (DPN)—an Indian perspective. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:957-960.

- Karampinis E, Georgopoulou KE, Kampra E, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic patterns of basal cell carcinoma and its mimickers in skin of color: a practical summary. Medicina (Kaunas). 2024;60:1386.

- Gorai S, Ahmad S, Raza SSM, et al. Update of pathophysiology and treatment options of seborrheic keratosis. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:E15934.

- Jain S, Caire H, Haas CJ. Management of dermatosis papulosa nigra: a systematic review. Int J Dermatol. Published online October 4, 2024.

- Garcia MS, Azari R, Eisen DB. Treatment of dermatosis papulosa nigra in 10 patients: a comparison trial of electrodesiccation, pulsed dye laser, and curettage. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1968-1972.

- Kundu RV, Joshi SS, Suh KY, et al. Comparison of electrodesiccation and potassium-titanyl-phosphate laser for treatment of dermatosis papulosa nigra. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1079-1083.

- Markiewicz E, Karaman-Jurukovska N, Mammone T, et al. Post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation in dark skin: molecular mechanism and skincare implications. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2022;15:2555-2565.

- Niang SO, Kane A, Diallo M, et al. Dermatosis papulosa nigra in Dakar, Senegal. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46(suppl 1):45-47.

- Taylor SC, Averyhart AN, Heath CR. Postprocedural wound-healing efficacy following removal of dermatosis papulosa nigra lesions in an African American population: a comparison of a skin protectant ointment and a topical antibiotic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(suppl 3):S30-S35.

Key Features of Dermatosis Papulosa Nigra vs Seborrheic Keratosis

Key Features of Dermatosis Papulosa Nigra vs Seborrheic Keratosis

Key Features of Dermatosis Papulosa Nigra vs Seborrheic Keratosis

Key Features of Dermatosis Papulosa Nigra vs Seborrheic Keratosis

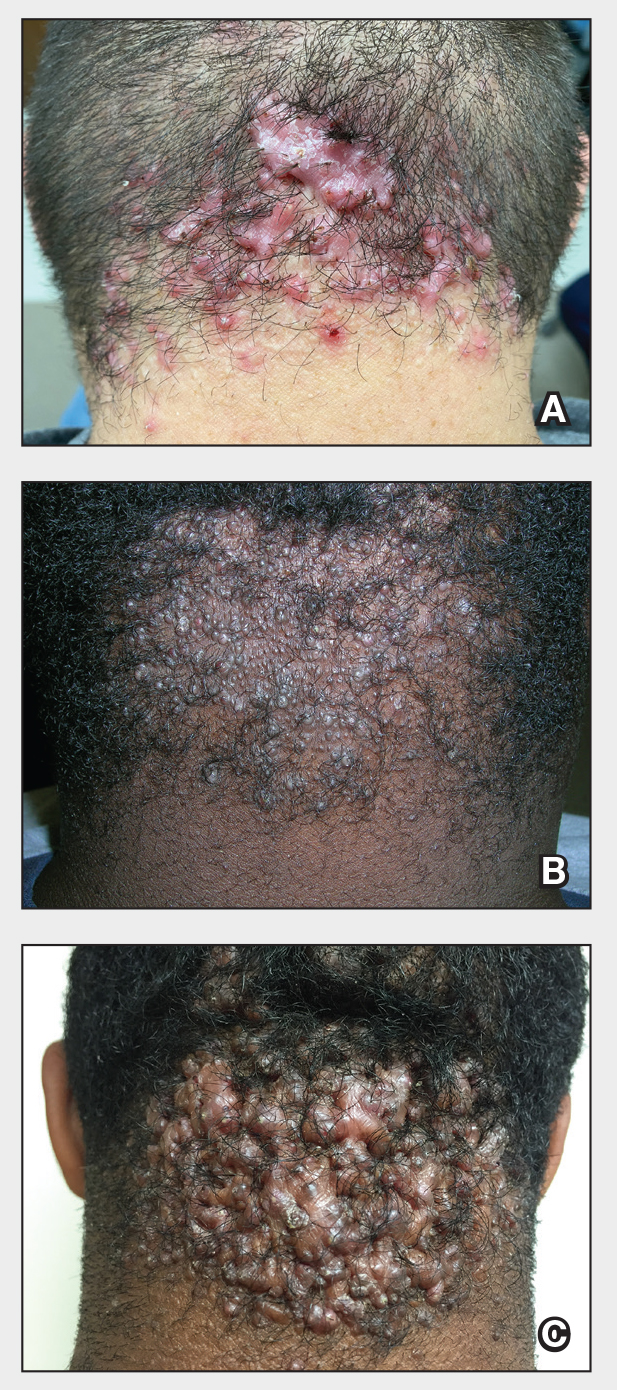

THE COMPARISON

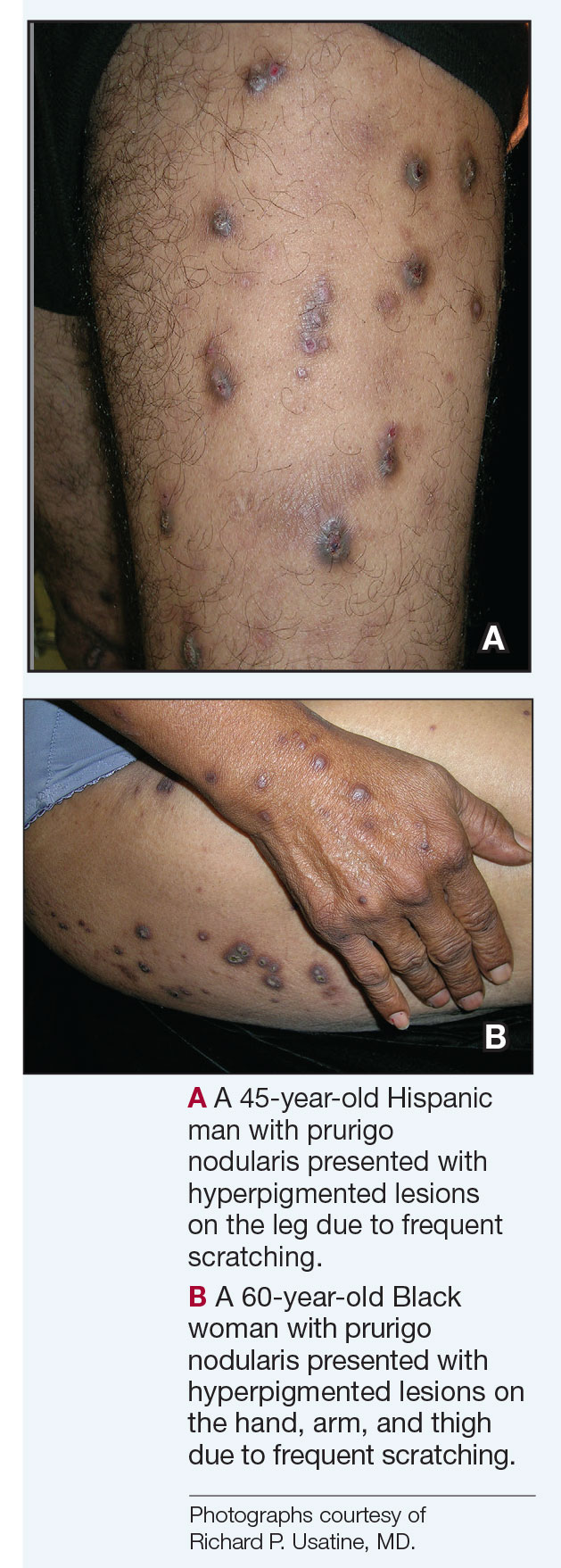

- A A Black woman with dermatosis papulosa nigra manifesting as a cluster of light brown flat seborrheic keratoses that covered the cheeks and lateral face and extended to the neck.

- B A Black man with dermatosis papulosa nigra manifesting as small black papules on the cheeks and eyelids involving the central face.

Dermatosis papulosa nigra (DPN), a subvariant of seborrheic keratosis (SK), is characterized by benign pigmented epidermal neoplasms that typically manifest on the face, neck, and trunk in individuals with darker skin tones.1,2 While DPN meets the diagnostic criteria for SK, certain characteristics can help distinguish these lesions from other SK types. Treatment of DPN in patients with skin of color requires caution, particularly regarding the use of abrasive methods as well as cryotherapy, which generally should be avoided.

Epidemiology

The incidence of SKs increases with age.3,4 Although it can occur in patients of all skin tones, SK is more common in lighter skin tones, while DPN predominantly is diagnosed in darker skin types.1,4 The prevalence of DPN in Black patients ranges from 10% to 30%, and Black women are twice as likely to be diagnosed with DPN as men.2 One study reported a first-degree relative with DPN in 84% (42/50) of patients.5 The number and size of DPN papules increase with age.1

Key Clinical Features

Dermatosis papulosa nigra and SK have distinctive morphologies: DPN typically manifests as raised, round or filiform, sessile, brown to black, 1- to 5-mm papules.2 Seborrheic keratoses tend to be larger with a “stuck on” appearance and manifest as well-demarcated, pink to black papules or plaques that can range in size from millimeters to a few centimeters.3,4 In DPN, the lesions usually are asymptomatic but may be tender, pruritic, dry, or scaly and may become irritated.1,2 They develop symmetrically in sun-exposed areas, and the most common sites are the malar face, temporal region, neck, and trunk.1,2,6,7 Seborrheic keratoses can appear throughout the body, including in sun-exposed areas, but have varying textures (eg, greasy, waxy, verrucous).3,4

Worth Noting

Dermatosis papulosa nigra and SK can resemble each other histologically: DPN demonstrates a fibrous stroma, papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis, and acanthosis at the intraepidermal layer, which are diagnostic criteria for SK.2,4,8 However, other histologic features characteristic of SK that are not seen in DPN include pseudohorn cysts, spindle tumor cells, and basaloid cell nests.8

Dermoscopy can be useful in ruling out malignant skin cancers when evaluating pigmented lesions. The most common dermoscopic features of SK are cerebriform patterns such as fissures and ridges, comedolike openings, and pigmented fingerprintlike structures.3,4 To a lesser degree, milialike cysts, sharp demarcation, and hairpin-shaped vascular structures also may be present.4 The dermoscopic findings of DPN have not been well evaluated, but one study revealed that DPN had similar dermoscopic features to SK with some predominant features.6 Ridges and fissures were seen in 59% of patients diagnosed with DPN followed by comedolike openings seen in 27% of patients. The coexistence of a cerebriform pattern with comedolike openings was infrequent, and milialike cysts were rare.6

While DPN and SK are benign, patients often seek treatment for cosmetic reasons. Factors to consider when choosing a treatment modality include location of the lesions, the patient’s skin tone, and postprocedural outcomes (eg, depigmentation, wound healing). In general, treatments for SK include cryotherapy, electrodesiccation and curettage, and topical therapeutics such as hydrogen peroxide 40%, topical vitamin D3, and nitric-zinc 30%-50% solutions.4,8 Well-established treatment options for DPN include electrodesiccation, laser therapies, scissor excision, and cryotherapy, but topical options such as tazarotene also have been reported.1,9 Of the treatments for DPN, electrodesiccation and laser therapy routinely are used.10

The efficacy of electrodessication and potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP) laser were assessed in a randomized, investigator-blinded split-face study.11 Both modalities received high improvement ratings, with the results favoring the KTP laser. The patients (most of whom were Black) reported that KTP laser was more effective but more painful than electrodessication (P=.002).11 In another randomized study, patients received 3 treatments—electrodessication, pulsed dye laser, and curettage—for select DPN papules.10 There was no difference in the degree of clearance, cosmetic outcome, or postinflammatory hyperpigmentation between the 3 modalities, but patients found the laser to be the most painful.

It is important to exercise caution when using abrasive methods (eg, laser therapy, electrodesiccation, curettage) in patients with darker skin tones because of the increased risk for postinflammatory pigment alteration.1,2,12 Adverse effects of treatment are a top concern in the management of DPN.5,13 While cryotherapy is a preferred treatment of SK in lighter skin tones, it generally is avoided for DPN in darker skin types because melanocyte destruction can lead to cosmetically unsatisfactory and easily visible depigmentation.9

To mitigate postprocedural adverse effects, proper aftercare can promote wound healing and minimize postinflammatory pigment alteration. In one split-face study of Black patients, 2 DPN papules were removed from each side of the face using fine-curved surgical scissors.14 Next, a petrolatum-based ointment and an antibiotic ointment with polymyxin B sulfate/bacitracin zinc was applied twice daily for 21 days to opposite sides of the face. Patients did not develop infection, tolerated both treatments well, and demonstrated improved general wound appearance according to investigator- rated clinical assessment.14 Other reported postprocedural approaches include using topical agents with ingredients shown to improve hyperpigmentation (eg, niacinamide, azelaic acid) as well as photoprotection.12

Health Disparity Highlight

While DPN is benign, it can have adverse psychosocial effects on patients. A study in Senegal revealed that 60% (19/30) of patients with DPN experienced anxiety related to their condition, while others noted that DPN hindered their social relationships.13 In one US study of 50 Black patients with DPN, there was a moderate effect on quality of life, and 36% (18/50) of patients had the lesions removed. However, of the treated patients, 67% (12/18) reported few—if any—symptoms prior to removal.5 Although treatment of DPN is widely considered a cosmetic procedure, therapeutic management can address—and may improve—mental health in patients with skin of color.1,5,13 Despite the high prevalence of DPN in patients with darker skin tones, data on treatment frequency and insurance coverage are not widely available, thus limiting our understanding of treatment accessibility and economic burden.

- Frazier WT, Proddutur S, Swope K. Common dermatologic conditions in skin of color. Am Fam Physician.2023;107:26-34.

- Metin SA, Lee BW, Lambert WC, et al. Dermatosis papulosa nigra: a clinically and histopathologically distinct entity. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:491-496.

- Braun RP, Ludwig S, Marghoob AA. Differential diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis: clinical and dermoscopic features. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017; 16: 835-842.

- Sun MD, Halpern AC. Advances in the etiology, detection, and clinical management of seborrheic keratoses. Dermatology. 2022;238:205-217.

- Uwakwe LN, De Souza B, Subash J, et al. Dermatosis papulosa nigra: a quality of life survey study. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13:17-19.

- Bhat RM, Patrao N, Monteiro R, et al. A clinical, dermoscopic, and histopathological study of dermatosis papulosa nigra (DPN)—an Indian perspective. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:957-960.

- Karampinis E, Georgopoulou KE, Kampra E, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic patterns of basal cell carcinoma and its mimickers in skin of color: a practical summary. Medicina (Kaunas). 2024;60:1386.

- Gorai S, Ahmad S, Raza SSM, et al. Update of pathophysiology and treatment options of seborrheic keratosis. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:E15934.

- Jain S, Caire H, Haas CJ. Management of dermatosis papulosa nigra: a systematic review. Int J Dermatol. Published online October 4, 2024.

- Garcia MS, Azari R, Eisen DB. Treatment of dermatosis papulosa nigra in 10 patients: a comparison trial of electrodesiccation, pulsed dye laser, and curettage. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1968-1972.

- Kundu RV, Joshi SS, Suh KY, et al. Comparison of electrodesiccation and potassium-titanyl-phosphate laser for treatment of dermatosis papulosa nigra. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1079-1083.

- Markiewicz E, Karaman-Jurukovska N, Mammone T, et al. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in dark skin: molecular mechanism and skincare implications. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2022;15: 2555-2565.

- Niang SO, Kane A, Diallo M, et al. Dermatosis papulosa nigra in Dakar, Senegal. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46(suppl 1):45-47.

- Taylor SC, Averyhart AN, Heath CR. Postprocedural wound-healing efficacy following removal of dermatosis papulosa nigra lesions in an African American population: a comparison of a skin protectant ointment and a topical antibiotic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(suppl 3):S30-S35.

THE COMPARISON

- A A Black woman with dermatosis papulosa nigra manifesting as a cluster of light brown flat seborrheic keratoses that covered the cheeks and lateral face and extended to the neck.

- B A Black man with dermatosis papulosa nigra manifesting as small black papules on the cheeks and eyelids involving the central face.

Dermatosis papulosa nigra (DPN), a subvariant of seborrheic keratosis (SK), is characterized by benign pigmented epidermal neoplasms that typically manifest on the face, neck, and trunk in individuals with darker skin tones.1,2 While DPN meets the diagnostic criteria for SK, certain characteristics can help distinguish these lesions from other SK types. Treatment of DPN in patients with skin of color requires caution, particularly regarding the use of abrasive methods as well as cryotherapy, which generally should be avoided.

Epidemiology

The incidence of SKs increases with age.3,4 Although it can occur in patients of all skin tones, SK is more common in lighter skin tones, while DPN predominantly is diagnosed in darker skin types.1,4 The prevalence of DPN in Black patients ranges from 10% to 30%, and Black women are twice as likely to be diagnosed with DPN as men.2 One study reported a first-degree relative with DPN in 84% (42/50) of patients.5 The number and size of DPN papules increase with age.1

Key Clinical Features

Dermatosis papulosa nigra and SK have distinctive morphologies: DPN typically manifests as raised, round or filiform, sessile, brown to black, 1- to 5-mm papules.2 Seborrheic keratoses tend to be larger with a “stuck on” appearance and manifest as well-demarcated, pink to black papules or plaques that can range in size from millimeters to a few centimeters.3,4 In DPN, the lesions usually are asymptomatic but may be tender, pruritic, dry, or scaly and may become irritated.1,2 They develop symmetrically in sun-exposed areas, and the most common sites are the malar face, temporal region, neck, and trunk.1,2,6,7 Seborrheic keratoses can appear throughout the body, including in sun-exposed areas, but have varying textures (eg, greasy, waxy, verrucous).3,4

Worth Noting

Dermatosis papulosa nigra and SK can resemble each other histologically: DPN demonstrates a fibrous stroma, papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis, and acanthosis at the intraepidermal layer, which are diagnostic criteria for SK.2,4,8 However, other histologic features characteristic of SK that are not seen in DPN include pseudohorn cysts, spindle tumor cells, and basaloid cell nests.8

Dermoscopy can be useful in ruling out malignant skin cancers when evaluating pigmented lesions. The most common dermoscopic features of SK are cerebriform patterns such as fissures and ridges, comedolike openings, and pigmented fingerprintlike structures.3,4 To a lesser degree, milialike cysts, sharp demarcation, and hairpin-shaped vascular structures also may be present.4 The dermoscopic findings of DPN have not been well evaluated, but one study revealed that DPN had similar dermoscopic features to SK with some predominant features.6 Ridges and fissures were seen in 59% of patients diagnosed with DPN followed by comedolike openings seen in 27% of patients. The coexistence of a cerebriform pattern with comedolike openings was infrequent, and milialike cysts were rare.6

While DPN and SK are benign, patients often seek treatment for cosmetic reasons. Factors to consider when choosing a treatment modality include location of the lesions, the patient’s skin tone, and postprocedural outcomes (eg, depigmentation, wound healing). In general, treatments for SK include cryotherapy, electrodesiccation and curettage, and topical therapeutics such as hydrogen peroxide 40%, topical vitamin D3, and nitric-zinc 30%-50% solutions.4,8 Well-established treatment options for DPN include electrodesiccation, laser therapies, scissor excision, and cryotherapy, but topical options such as tazarotene also have been reported.1,9 Of the treatments for DPN, electrodesiccation and laser therapy routinely are used.10

The efficacy of electrodessication and potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP) laser were assessed in a randomized, investigator-blinded split-face study.11 Both modalities received high improvement ratings, with the results favoring the KTP laser. The patients (most of whom were Black) reported that KTP laser was more effective but more painful than electrodessication (P=.002).11 In another randomized study, patients received 3 treatments—electrodessication, pulsed dye laser, and curettage—for select DPN papules.10 There was no difference in the degree of clearance, cosmetic outcome, or postinflammatory hyperpigmentation between the 3 modalities, but patients found the laser to be the most painful.

It is important to exercise caution when using abrasive methods (eg, laser therapy, electrodesiccation, curettage) in patients with darker skin tones because of the increased risk for postinflammatory pigment alteration.1,2,12 Adverse effects of treatment are a top concern in the management of DPN.5,13 While cryotherapy is a preferred treatment of SK in lighter skin tones, it generally is avoided for DPN in darker skin types because melanocyte destruction can lead to cosmetically unsatisfactory and easily visible depigmentation.9

To mitigate postprocedural adverse effects, proper aftercare can promote wound healing and minimize postinflammatory pigment alteration. In one split-face study of Black patients, 2 DPN papules were removed from each side of the face using fine-curved surgical scissors.14 Next, a petrolatum-based ointment and an antibiotic ointment with polymyxin B sulfate/bacitracin zinc was applied twice daily for 21 days to opposite sides of the face. Patients did not develop infection, tolerated both treatments well, and demonstrated improved general wound appearance according to investigator- rated clinical assessment.14 Other reported postprocedural approaches include using topical agents with ingredients shown to improve hyperpigmentation (eg, niacinamide, azelaic acid) as well as photoprotection.12

Health Disparity Highlight

While DPN is benign, it can have adverse psychosocial effects on patients. A study in Senegal revealed that 60% (19/30) of patients with DPN experienced anxiety related to their condition, while others noted that DPN hindered their social relationships.13 In one US study of 50 Black patients with DPN, there was a moderate effect on quality of life, and 36% (18/50) of patients had the lesions removed. However, of the treated patients, 67% (12/18) reported few—if any—symptoms prior to removal.5 Although treatment of DPN is widely considered a cosmetic procedure, therapeutic management can address—and may improve—mental health in patients with skin of color.1,5,13 Despite the high prevalence of DPN in patients with darker skin tones, data on treatment frequency and insurance coverage are not widely available, thus limiting our understanding of treatment accessibility and economic burden.

THE COMPARISON

- A A Black woman with dermatosis papulosa nigra manifesting as a cluster of light brown flat seborrheic keratoses that covered the cheeks and lateral face and extended to the neck.

- B A Black man with dermatosis papulosa nigra manifesting as small black papules on the cheeks and eyelids involving the central face.

Dermatosis papulosa nigra (DPN), a subvariant of seborrheic keratosis (SK), is characterized by benign pigmented epidermal neoplasms that typically manifest on the face, neck, and trunk in individuals with darker skin tones.1,2 While DPN meets the diagnostic criteria for SK, certain characteristics can help distinguish these lesions from other SK types. Treatment of DPN in patients with skin of color requires caution, particularly regarding the use of abrasive methods as well as cryotherapy, which generally should be avoided.

Epidemiology

The incidence of SKs increases with age.3,4 Although it can occur in patients of all skin tones, SK is more common in lighter skin tones, while DPN predominantly is diagnosed in darker skin types.1,4 The prevalence of DPN in Black patients ranges from 10% to 30%, and Black women are twice as likely to be diagnosed with DPN as men.2 One study reported a first-degree relative with DPN in 84% (42/50) of patients.5 The number and size of DPN papules increase with age.1

Key Clinical Features

Dermatosis papulosa nigra and SK have distinctive morphologies: DPN typically manifests as raised, round or filiform, sessile, brown to black, 1- to 5-mm papules.2 Seborrheic keratoses tend to be larger with a “stuck on” appearance and manifest as well-demarcated, pink to black papules or plaques that can range in size from millimeters to a few centimeters.3,4 In DPN, the lesions usually are asymptomatic but may be tender, pruritic, dry, or scaly and may become irritated.1,2 They develop symmetrically in sun-exposed areas, and the most common sites are the malar face, temporal region, neck, and trunk.1,2,6,7 Seborrheic keratoses can appear throughout the body, including in sun-exposed areas, but have varying textures (eg, greasy, waxy, verrucous).3,4

Worth Noting

Dermatosis papulosa nigra and SK can resemble each other histologically: DPN demonstrates a fibrous stroma, papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis, and acanthosis at the intraepidermal layer, which are diagnostic criteria for SK.2,4,8 However, other histologic features characteristic of SK that are not seen in DPN include pseudohorn cysts, spindle tumor cells, and basaloid cell nests.8

Dermoscopy can be useful in ruling out malignant skin cancers when evaluating pigmented lesions. The most common dermoscopic features of SK are cerebriform patterns such as fissures and ridges, comedolike openings, and pigmented fingerprintlike structures.3,4 To a lesser degree, milialike cysts, sharp demarcation, and hairpin-shaped vascular structures also may be present.4 The dermoscopic findings of DPN have not been well evaluated, but one study revealed that DPN had similar dermoscopic features to SK with some predominant features.6 Ridges and fissures were seen in 59% of patients diagnosed with DPN followed by comedolike openings seen in 27% of patients. The coexistence of a cerebriform pattern with comedolike openings was infrequent, and milialike cysts were rare.6

While DPN and SK are benign, patients often seek treatment for cosmetic reasons. Factors to consider when choosing a treatment modality include location of the lesions, the patient’s skin tone, and postprocedural outcomes (eg, depigmentation, wound healing). In general, treatments for SK include cryotherapy, electrodesiccation and curettage, and topical therapeutics such as hydrogen peroxide 40%, topical vitamin D3, and nitric-zinc 30%-50% solutions.4,8 Well-established treatment options for DPN include electrodesiccation, laser therapies, scissor excision, and cryotherapy, but topical options such as tazarotene also have been reported.1,9 Of the treatments for DPN, electrodesiccation and laser therapy routinely are used.10

The efficacy of electrodessication and potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP) laser were assessed in a randomized, investigator-blinded split-face study.11 Both modalities received high improvement ratings, with the results favoring the KTP laser. The patients (most of whom were Black) reported that KTP laser was more effective but more painful than electrodessication (P=.002).11 In another randomized study, patients received 3 treatments—electrodessication, pulsed dye laser, and curettage—for select DPN papules.10 There was no difference in the degree of clearance, cosmetic outcome, or postinflammatory hyperpigmentation between the 3 modalities, but patients found the laser to be the most painful.

It is important to exercise caution when using abrasive methods (eg, laser therapy, electrodesiccation, curettage) in patients with darker skin tones because of the increased risk for postinflammatory pigment alteration.1,2,12 Adverse effects of treatment are a top concern in the management of DPN.5,13 While cryotherapy is a preferred treatment of SK in lighter skin tones, it generally is avoided for DPN in darker skin types because melanocyte destruction can lead to cosmetically unsatisfactory and easily visible depigmentation.9

To mitigate postprocedural adverse effects, proper aftercare can promote wound healing and minimize postinflammatory pigment alteration. In one split-face study of Black patients, 2 DPN papules were removed from each side of the face using fine-curved surgical scissors.14 Next, a petrolatum-based ointment and an antibiotic ointment with polymyxin B sulfate/bacitracin zinc was applied twice daily for 21 days to opposite sides of the face. Patients did not develop infection, tolerated both treatments well, and demonstrated improved general wound appearance according to investigator- rated clinical assessment.14 Other reported postprocedural approaches include using topical agents with ingredients shown to improve hyperpigmentation (eg, niacinamide, azelaic acid) as well as photoprotection.12

Health Disparity Highlight