User login

Comprehensive Genomic Profiles of Melanoma in Veterans Compared to Reference Databases

Comprehensive Genomic Profiles of Melanoma in Veterans Compared to Reference Databases

The veteran population, with its unique and diverse types of exposure and military service experiences, faces distinct health factors compared with the general population. These factors can be categorized into exposures during military service and those occurring postservice. While the latter phase incorporates psychological issues that may arise while transitioning to civilian life, the service period is associated with major physical, chemical, and psychological exposures that can impact veterans’ health. Carcinogenesis related to military exposures is concerning, and different types of malignancies have been associated with military exposures.1 The 2022 introduction of the Cancer Moonshot initiative served as a breeding ground for multiple projects aimed at investigation of exposure-related carcinogenesis, prompting increased attention and efforts to linking specific exposures to specific malignancies.2

Melanoma is the deadliest skin cancer, accounting for 1.3% of all cancer deaths.3 Although it may only account for 1% to 5% of skin cancer diagnoses, its incidence in the United States’ population has been increasing.4,5 There were 97,610 estimated new cases of melanoma in 2023, according to the National Cancer Institute.6

The incidence of melanoma may be higher in the military population compared with the general population.7 Melanoma is the fourth-most common cancer diagnosed in veterans.8

Several demographic characteristics of the US military population are associated with higher melanoma incidence and poorer prognosis, including male sex, older age, and White race. Apart from sun exposure—a known risk factor for melanoma development—other factors, such as service branch, seem to contribute to risk, with the highest melanoma rates noted in the Air Force.9 According to a study by Chang et al, veterans have a higher risk of stage III (18%) or stage IV (13%) melanoma at initial diagnosis.8

Molecular testing of metastatic melanoma is currently the standard of care for guiding the use of US Food and Drug Administration-approved targeted therapies such as BRAF, MEK, and KIT inhibitors. This comparative analysis details the melanoma comprehensive genomic profiles observed at a large US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center (VAMC) and those reported in reference databases.

Methods

A query to select all metastatic melanomas sent for comprehensive genomic profiling from the Kansas City VAMC (KCVAMC), identified 35 cases from 2019 through 2023 as the study population. The health records of these patients were reviewed to collect demographic information, military service history, melanoma history, other medical, social, and family histories. The comprehensive genomic profiling reports were reviewed to collect the reported pathogenic variants, microsatellite instability (MSI) status, and tumor mutational burden (TMB) for each case.

The Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) was used to identify the most commonly mutated genes in melanomas from The Cancer Genome Atlas for the general population.4,5 The literature was consulted to determine the MSI status and TMB in melanomas from The Cancer Genome Atlas for separate reference populations.6,7 The frequency of MSI-high (MSI-H) status, TMB ≥ 10 mutations/megabase (mut/Mb), and mutations in each of the 20 most commonly mutated genes was determined and compared between melanomas from The Cancer Genome Atlas and KCVAMC cases. Corresponding P values were calculated to identify significant differences. Values were calculated for the entire sample as well as a subgroup with Agent Orange (AO) exposure. The study was approved by the KCVAMC Institutional Review Board.

Results

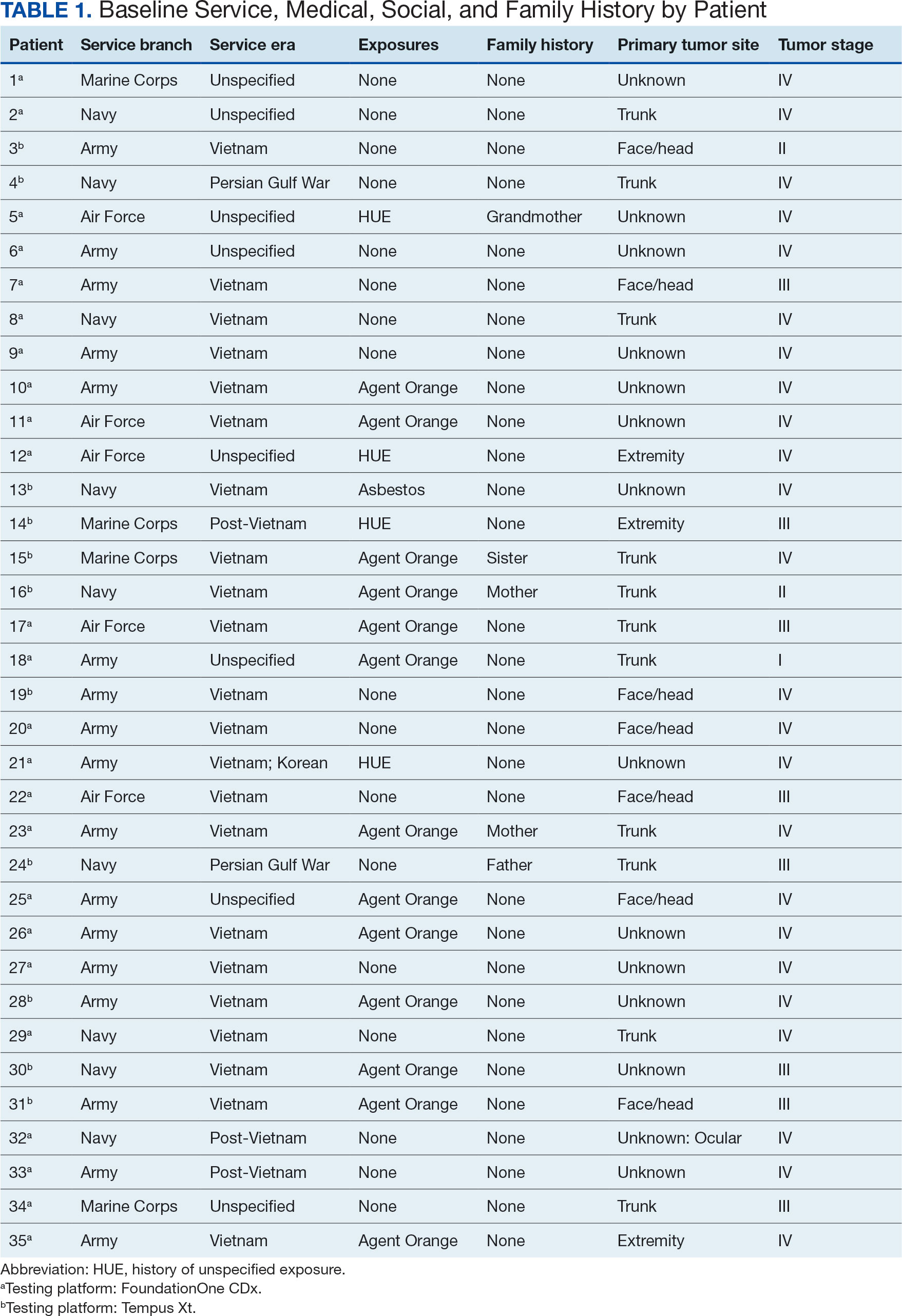

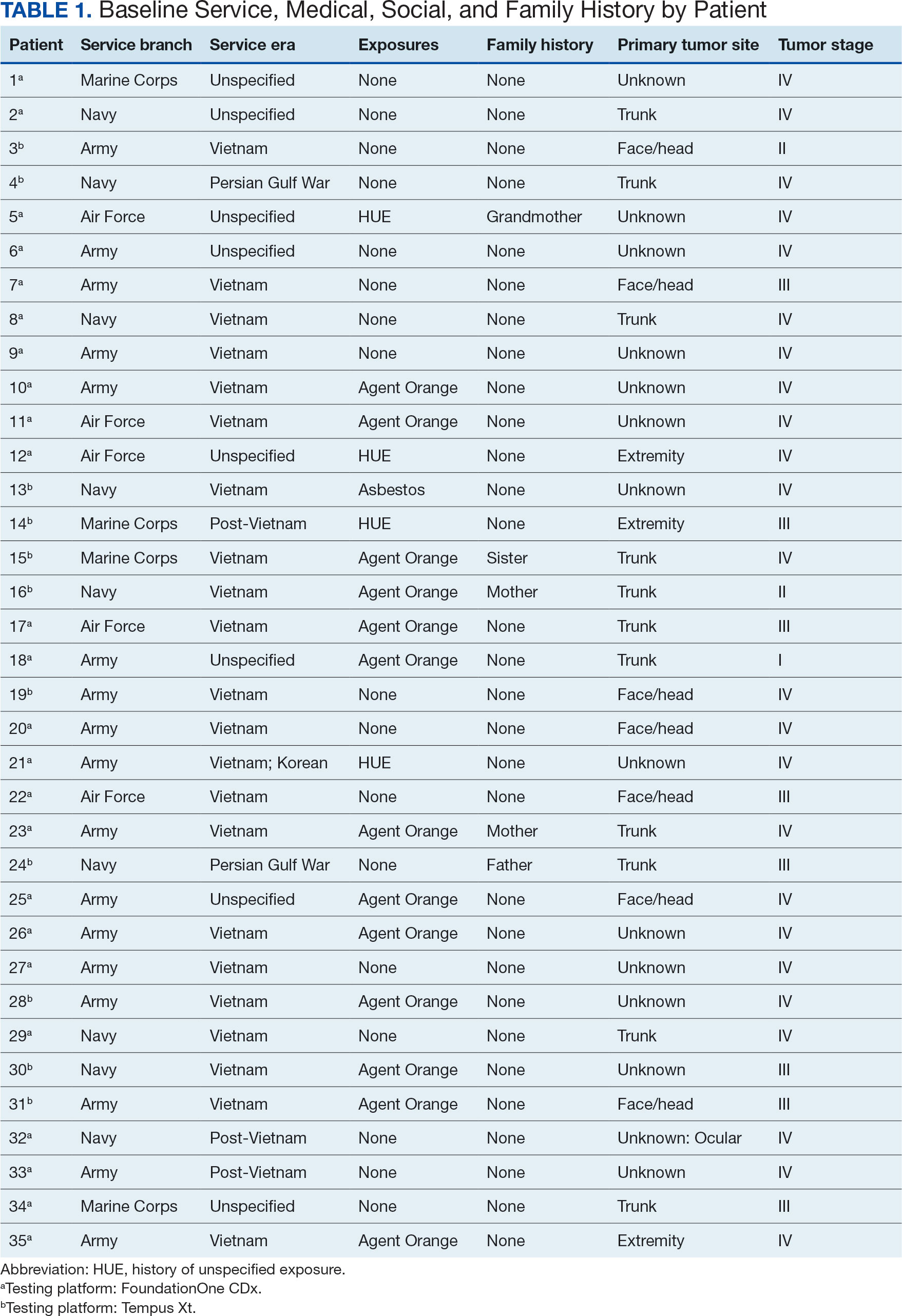

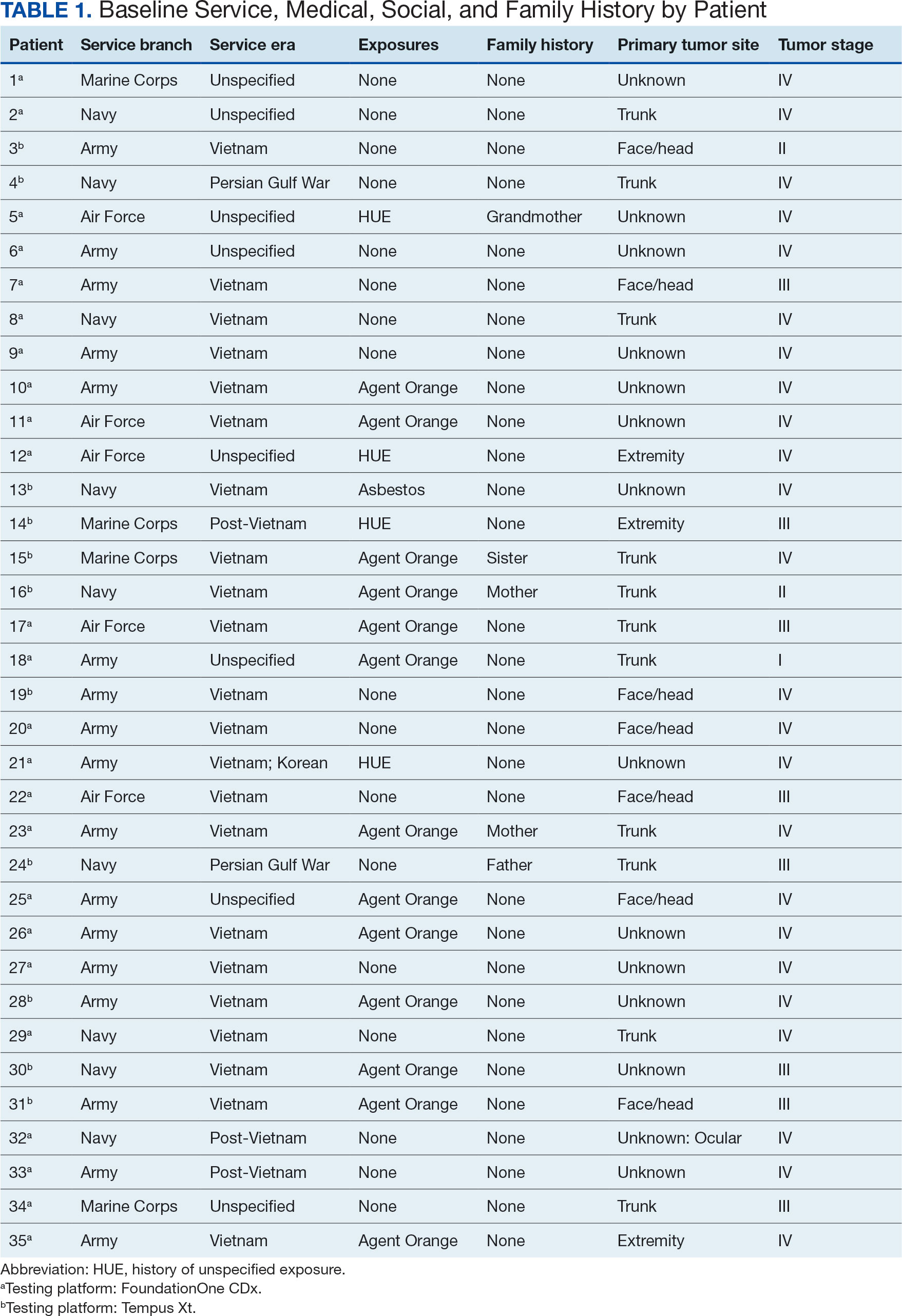

The mean (SD) age of study participants was 72.9 (9.4) years (range, 39-90 years). The mean (SD) duration of military service was 1654 (1421) days (about 4 years, 6 months, and 10 days). Of the 35 patients included, 22 (63%) served during the Vietnam era (November 1, 1965, to April 30, 1975) and 2 (6%) served during the Persian Gulf War era (August 2, 1990, to February 28, 1991). Seventeen veterans (49%) served in the Army, 9 in the Navy (26%), 5 in the Air Force (14%), and 4 in the Marine Corps (11%). Definitive AO exposure was noted in 13 patients (37%) (Table 1).

Of the 35 patients, 24 (69%) had metastatic disease and the primary site of melanoma was unknown in 14 patients (40%). One patient (Patient 32) had an intraocular melanoma. The primary site was the trunk for 11 patients (31%), the face/head for 7 patients (20%) and extremities for 3 patients (9%). Eight patients (23%) were pT3 stage (thickness > 2 mm but < 4 mm), 7 patients (20%) were pT4 stage (thickness > 4 mm), and 5 patients (14%) were pT1 (thickness ≥ 1 mm). One patient had a primary lesion at pT2 stage, and 1 had a Tis stage lesion. Three patients (9%) had a family history of melanoma in a first-degree relative.

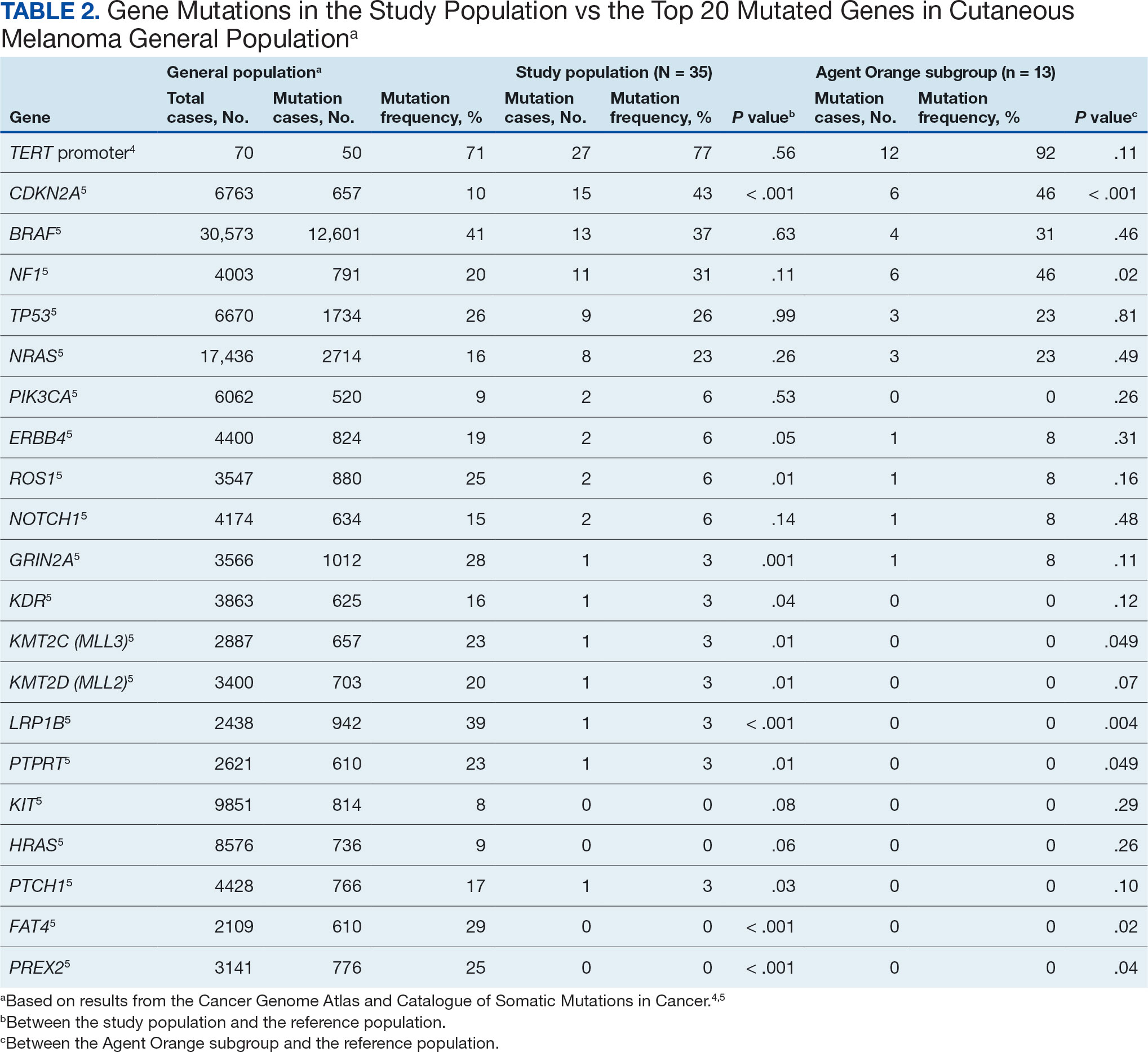

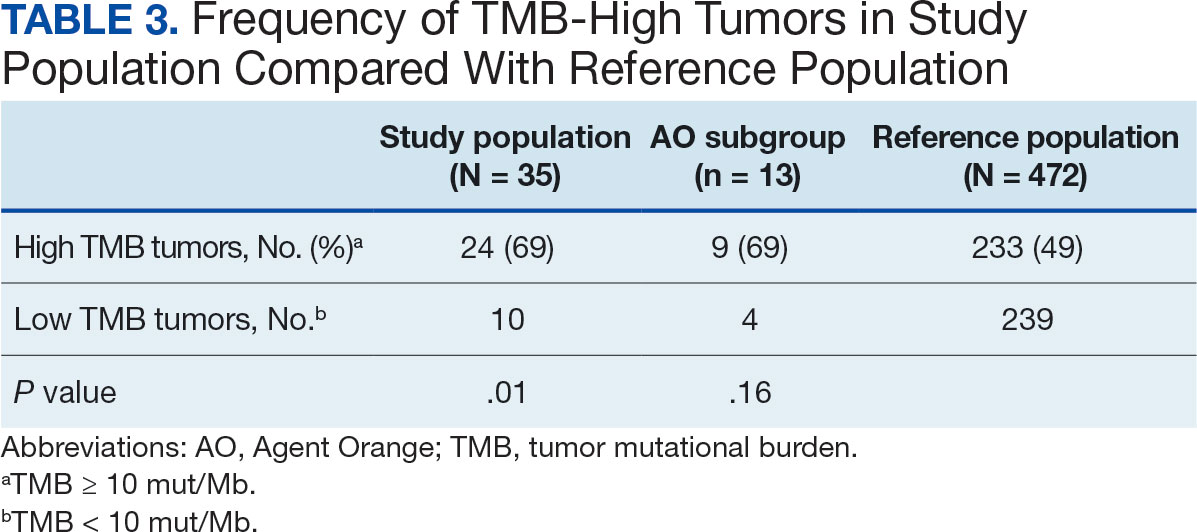

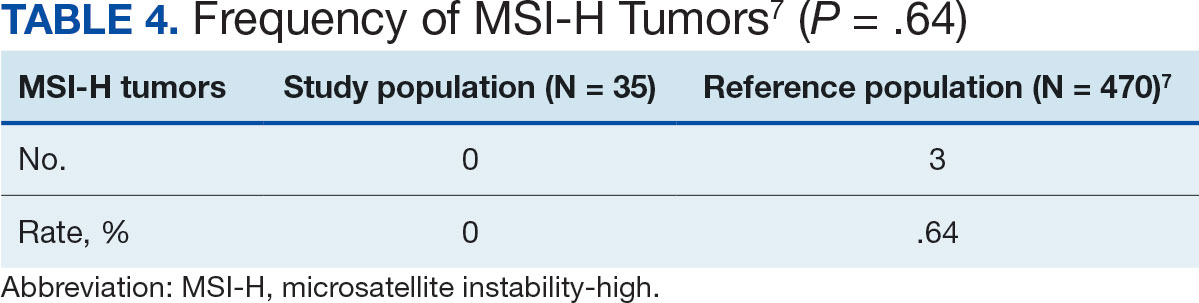

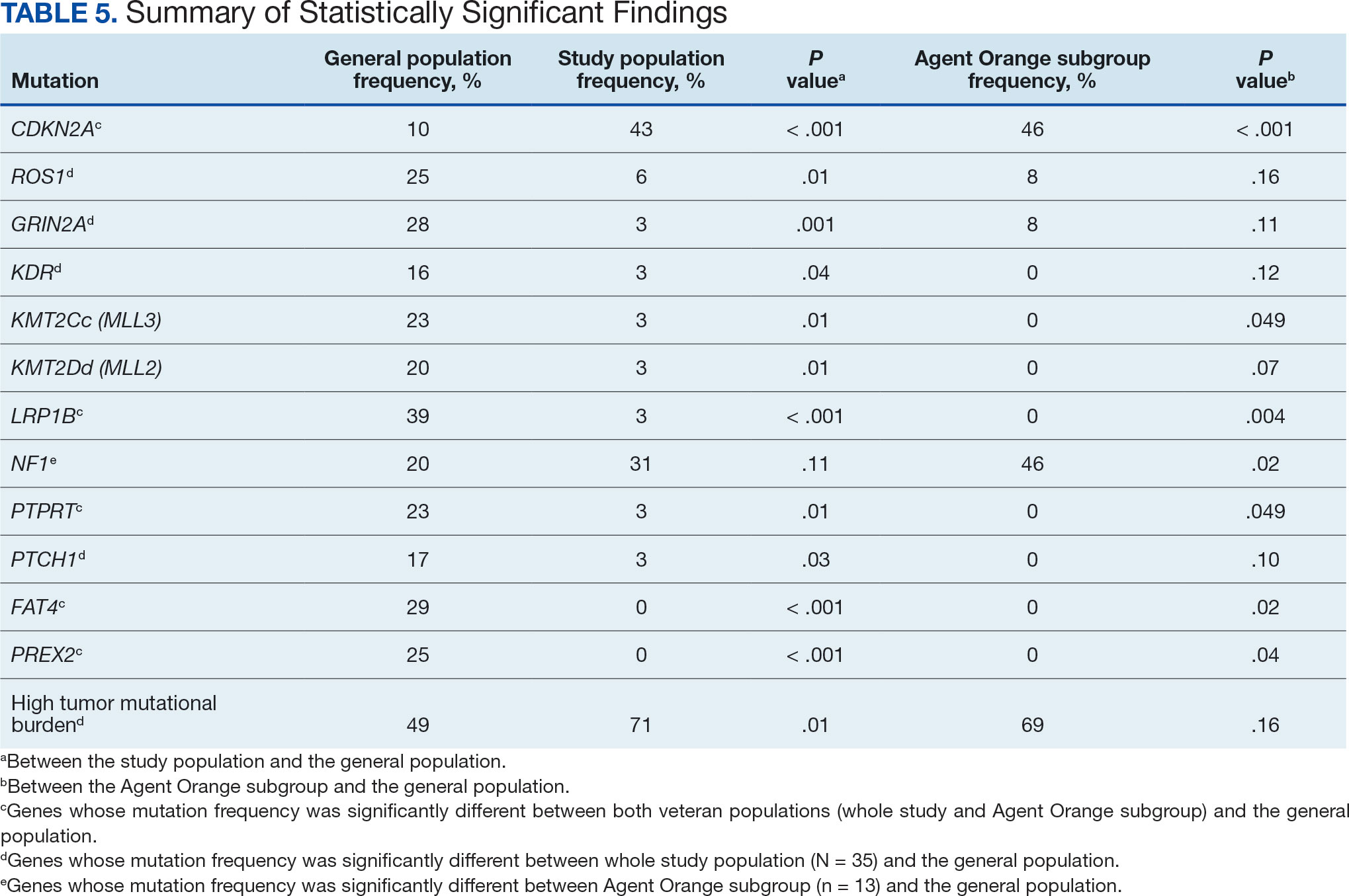

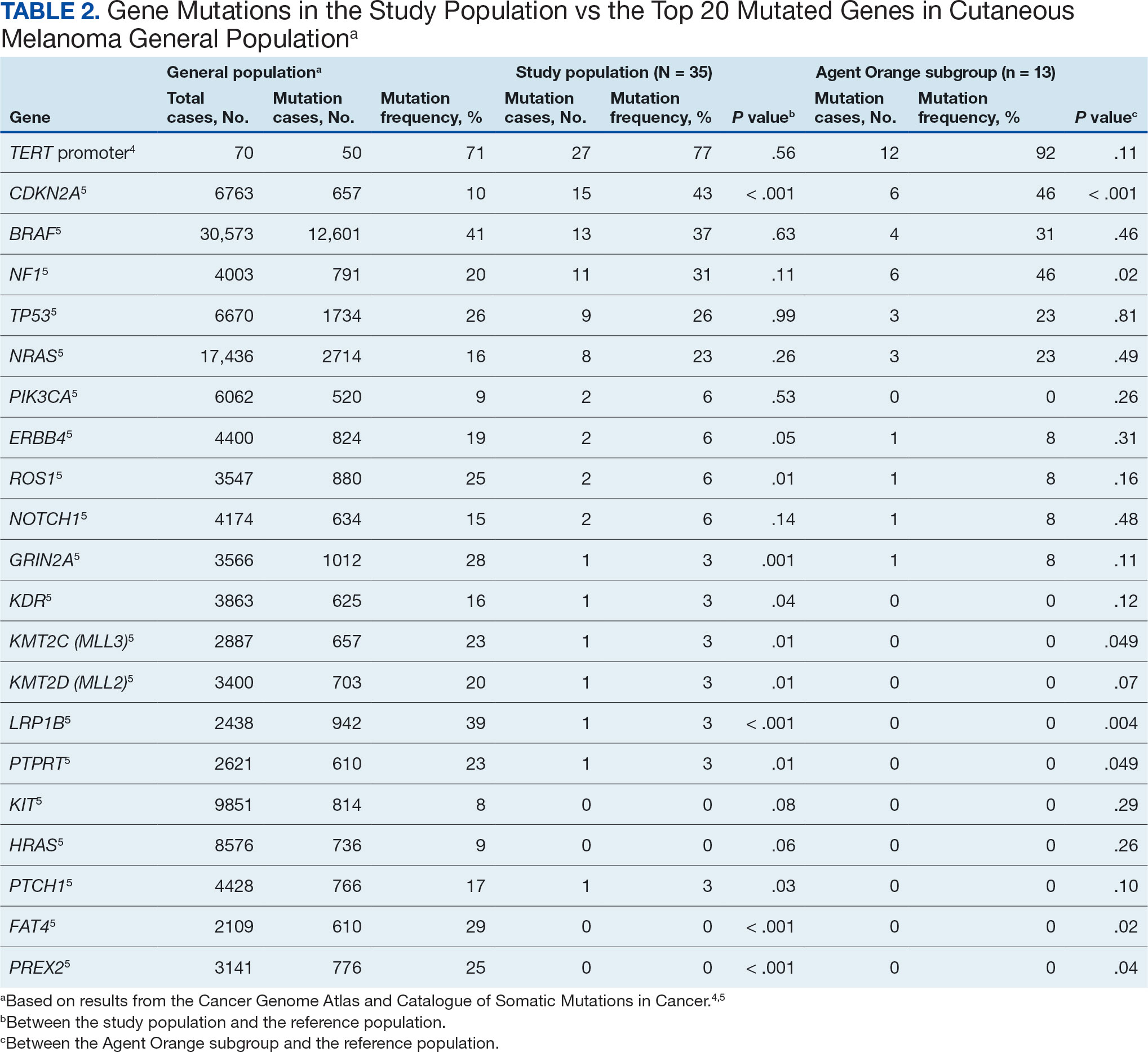

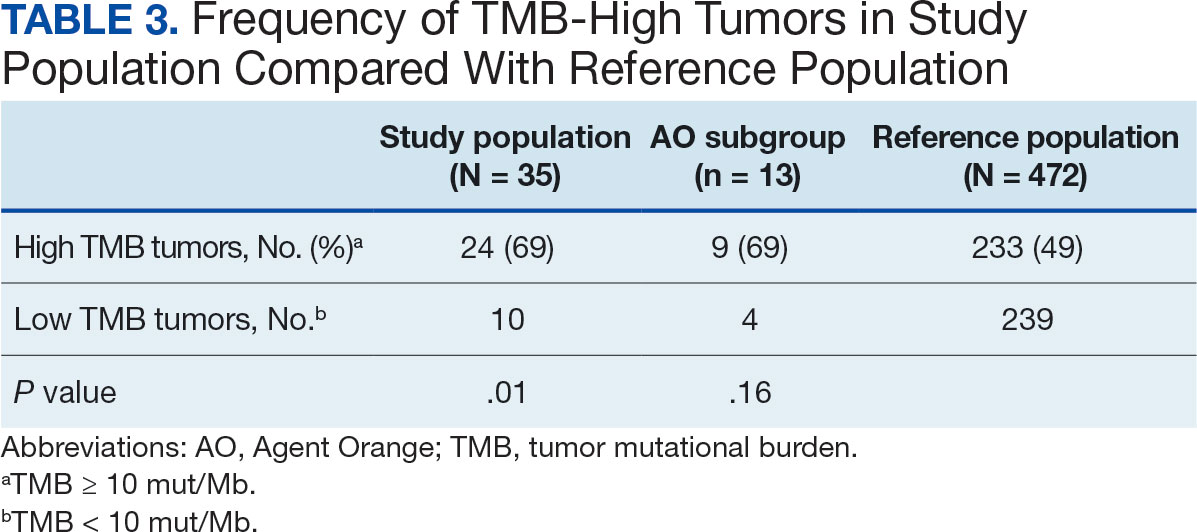

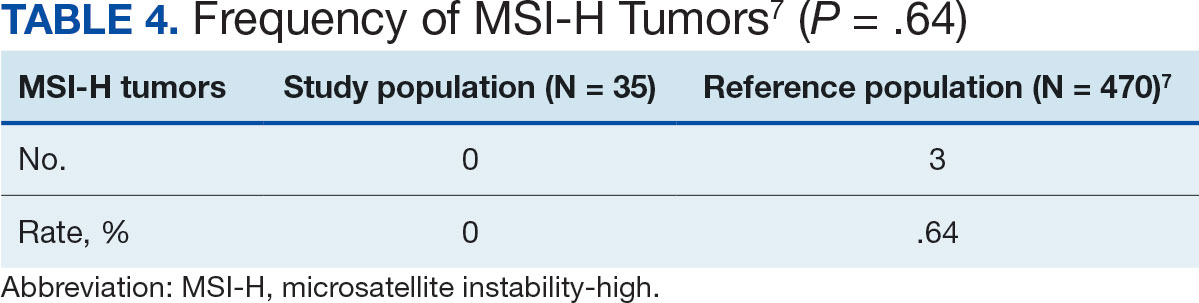

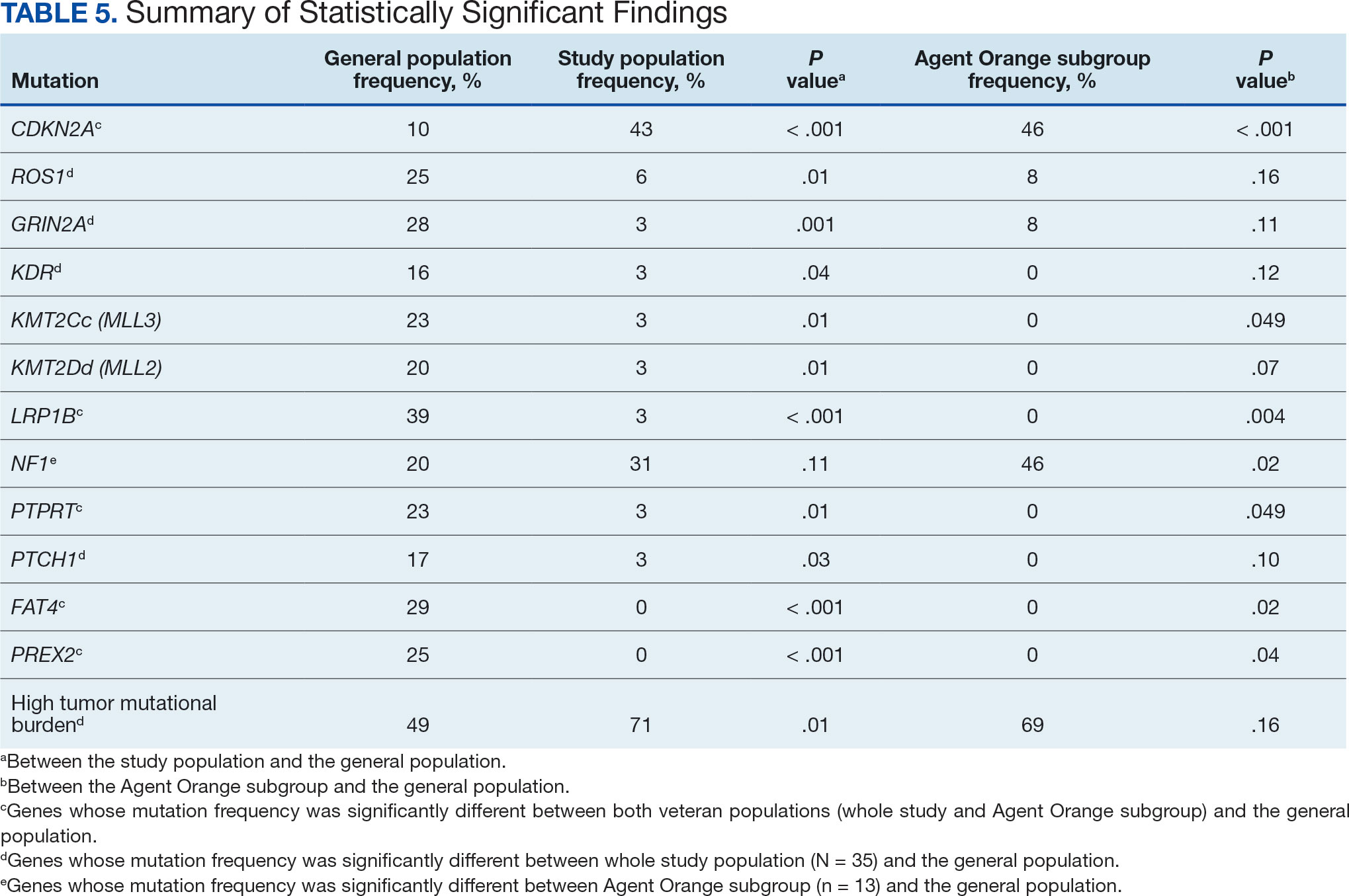

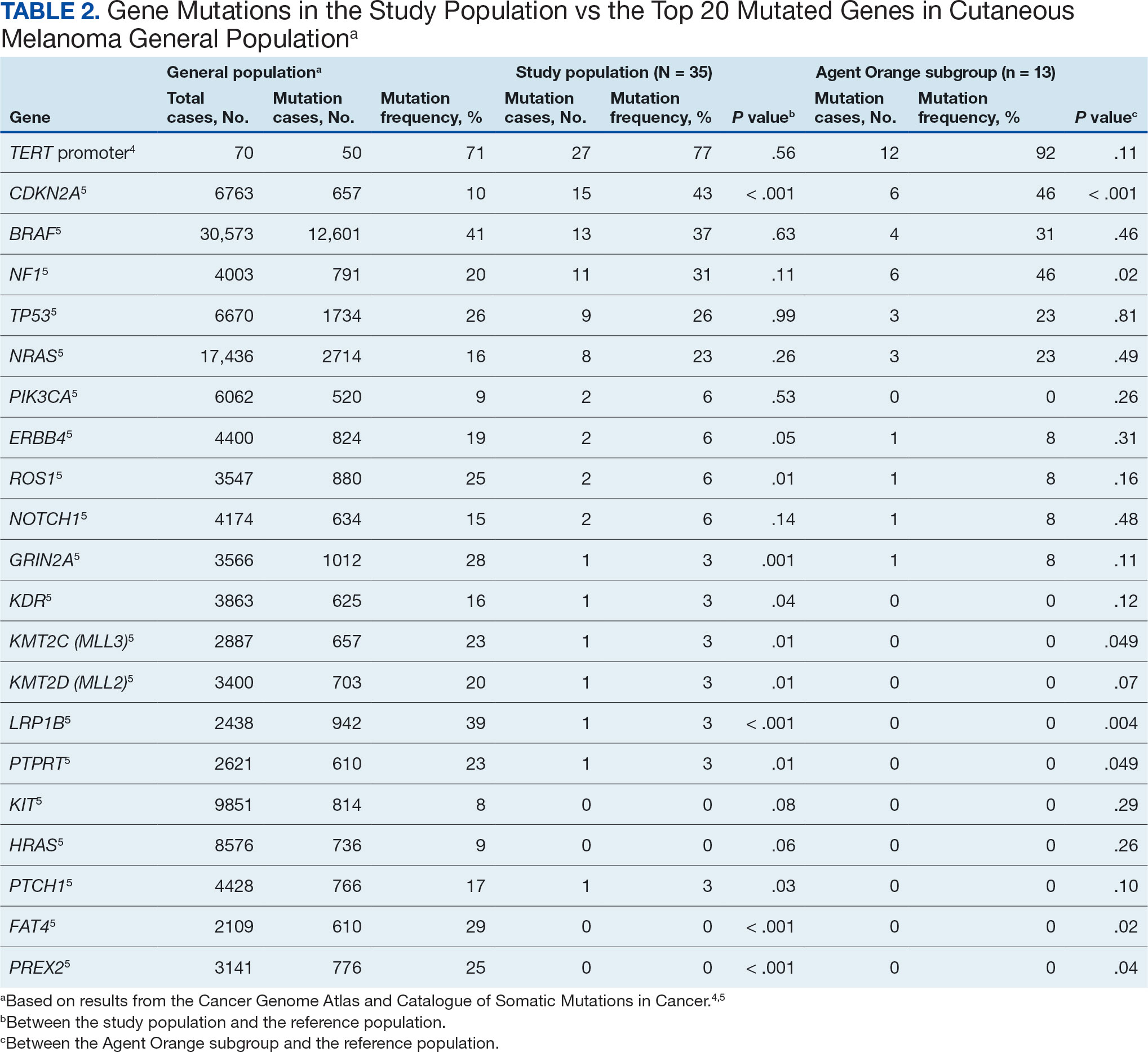

The list of genes mutated in melanoma cells in the study population is provided in the eAppendix.10,11 Twenty-seven patients (77%) had mutations in TERT promoter, 15 (43%) in CDKN2A/B, 13 (37%) in BRAF, 11 (31%) in NF1, 9 (26%) in TP53, and 8 (23%) in NRAS (Table 2). The majority of mutations in TERT promoter were c.- 146C>T (18 of 27 patients [67%]), whereas c.-124C>T was the second-most common (8 of 27 patients [30%]). The 2 observed mutations in the 13 patients with BRAF mutations were V600E and V600K, with almost equal distribution (54% and 46%, respectively). The mean (SD) TMB was 33.2 (39) mut/Mb (range, 1-203 mut/Mb). Ten patients (29%) had a TMB < 10 mut/Mb, whereas 24 (69%) had a TMB > 10 mut/Mb. The TMB could not be determined in 1 case. The frequency of TMB-high tumors in the study population compared with frequency in the reference population is shown in Table 3.12 Only 3 patients (0.64%) in the reference population had MSI-H tumors, and the microsatellite status could not be determined in those tumors (Table 4).13 Table 5 outlines statistically significant findings.

Agent Orange Subgroup

AO was a tactical herbicide used by the US military, named for the orange band around the storage barrels. Possible mutagenic properties of AO have been attributed to its byproduct, dioxin. Among the most common cancers known to be associated with AO exposure are bladder and prostate carcinoma and hematopoietic neoplasms. The association between genetic alterations and AO exposure was studied in veterans with prostate cancer.14 However, to our knowledge, insufficient information is available to determine whether an association exists between exposure to herbicides used in Vietnam or the contaminant dioxin and melanoma. Because a significant proportion of this study population had a well-documented history of AO exposure (37.1%), we were able to analyze them as a subgroup and to separately compare their mutation frequency with the general population.

Results were notable for different distributions of the most frequently mutated genes in the AO subgroup compared with the whole study population. As such, TERT promoter remained the most frequently mutated gene (92%), followed by CDKN2A/B (46%); however, frequency of mutations in NF1 (46%) outnumbered those of BRAF (31%), the fourth-most common mutation. Moreover, when compared with the general melanoma population, a significantly higher frequency of mutations in the NF1 gene was observed in the AO subgroup—not the entire study population.

Discussion

Given that veterans constitute a distinct population, there is reasonable interest in investigating characteristic health issues related to military service. Skin cancer—melanoma in particular—has been researched recently in a veteran population. The differences in demographics, tumor characteristics, and melanoma- specific survival in veterans compared with the general population have already been assessed. According to Chang et al, compared with the general population, veterans are more likely to present with metastatic disease and have lower 5-year survival rates.8

Melanoma is one of the most highly mutated malignancies.15 Fortunately, the most common mutation in melanoma, BRAF V600E, is now considered therapeutically targetable. However, there are still many mutations that are less often discussed and not well understood. Regardless of therapeutic implications, all mutations observed in melanoma are worth investigating because a tumor’s genomic profile also can provide prognostic and etiologic information. Developing comprehensive descriptions of melanoma mutational profiles in specific populations is critical to advancing etiologic understanding and informing prevention strategies.

Our results demonstrate the high prevalence of TERT promoter mutations with characteristic ultraviolet signature (C>T) in the study population. This aligns with general evidence that TERT promoter mutations are common in cutaneous melanomas: 77% of this study sample and up to 86% of all mutations are TERT promoter mutations, according to Davis et al.15 TERT promoter mutations are positively associated with the initiation, invasion, and metastasis of melanoma. In certain subtypes, there is evidence that the presence of TERT promoter mutations is significantly associated with risk for extranodal metastasis and death.16 The second-most common mutated gene in the veteran study population was CDKN2A/B (43%), and the third-most mutated gene was BRAF (37%).

In chronically sun-exposed skin NF1, NRAS, and occasionally BRAF V600K mutations tend to predominate. BRAF V600E mutations, on the other hand, are rare in these melanomas.15 In our study population, the most prevalent melanoma site was the trunk (31%), which is considered a location with an intermittent pattern of sun exposure.17

This study population also had a higher frequency of CDKN2A/B mutations. High frequencies of CDKN2A/B mutations have been reported in familial melanomas, but only 1 patient with CDKN2A/B mutations had a known family history of melanoma.15 Tumors in the study population showed significantly lower frequency of mutations in ROS1, GRIN2A, KDR, KMT2C (MLL3), KMT2D (MLL2), LRP1B, PTPRT, PTCH1, FAT4, and PREX2 (P < .05).

In this study the subgroup of veterans with AO exposure differed from the whole study population. As such, CDKN2A/B mutations were observed with the same frequency as NF1 mutations (46% each); however, BRAF mutations constituted only 31% of the mutations. In addition, the frequency of NF1 mutations was significantly higher in the AO subgroup compared with the general population, but not in the whole study population.

Our sample also differed from the reference population by showing a significantly higher frequency of TMB-high (ie, ≥ 10 mut/Mb) tumors (71% vs 49%; P = .01).12 Interestingly, no significant difference in the frequency of TMB-high tumors was observed between the AO subgroup and the reference population (69% vs 49%; P = .16). There also was no statistically significant difference between the frequency of MSI-H tumors in our study population and the reference population (P = .64).13

One patient in the study population had uveal melanoma. Mutations encountered in this patient’s tumor differed from the general mutational profile of tumors. None of the 21 mutations depicted in Table 2 were present in this sample.10,11 On the other hand, those mutations frequently observed in intraocular melanomas, BAP1 and GNA11, were present in this patient.18 Additionally, this particular melanoma possessed mutations in genes RICTOR, RAD21, and PIK3R1.

Limitations

This study population consisted exclusively of male patients, introducing sex as a potential confounder in analyzing differences between the study population and the general population. As noted in a 2020 systematic review, there were no sex-based differences in the frequency of mutations in BRAF, NRAS, and KIT genes.19

Regarding NF1 mutations, only NF1-mutated acral and mucosal melanomas were more frequently observed in female patients, whereas nonacral NF1-mutated melanomas were more frequently observed in male patients.20 However, there is currently no clear evidence of whether the mutational landscapes of cutaneous melanoma differ by sex.21 Among the 11 cases with NF1-mutatation, site of origin was known in 6, 5 of which originated at nonacral sites. Although the AO subgroup also consisted entirely of male patients, this does not explain the observed increased frequency of NF1 mutations relative to the general population. No such difference was observed between the whole study population, which also consisted exclusively of male patients, and the general population. The similar frequencies of nonacral location in the whole study population (3 acral, 18 nonacral, 14 unknown site of origin) and AO subgroup (1 acral, 7 nonacral, 5 unknown site of origin) preclude location as an explanation.

The Cancer Genome Atlas Network proposed a framework for genomic classification of melanoma into 4 subtypes based on the pattern of the most prevalent significantly mutated genes: mutant BRAF, mutant RAS, mutant NF1, and triple–wild-type. According to that study, BRAF mutations were indeed associated with younger age, in contrast to the NF1-mutant genomic subtype, which was more prevalent in older individuals with higher TMB.22 This emphasizes the need to interpret the potential association of AO exposure and NF1 mutation in melanoma with caution, although additional studies are required to observe the difference between the veteran population and age-matched general population.

On the other hand, Yu et al reported no significant differences of TMB values between patients aged < 60 and ≥ 60 years with melanoma.23 In short, the observed differences we report in our limited study warrant additional investigation with larger sample sizes, sex-matched controlling, and age-matched controlling. The study was limited by its small sample size and the single location.

Conclusion

The genomic profile of melanomas in the veteran population appears to be similar to that of the general population with a few possible differences. Melanomas in the veteran study population showed a higher frequency of CDKN2A/B mutations; lower frequency of ROS1, GRIN2A, KDR, KMT2C (MLL3), KMT2D (MLL2), LRP1B, PTPRT, PTCH1, FAT4, and PREX2 mutations; and higher TMB. In addition, melanomas in the AO subgroup showed higher frequencies of NF1 mutations. The significance of such findings remains to be determined by further investigation.

- Bytnar JA, McGlynn KA, et al. Cancer incidence in the US military: An updated analysis. Cancer. 2024;130(1):96-106. doi:10.1002/cncr.34978

- Singer DS. A new phase of the Cancer Moonshot to end cancer as we know it. Nat Med. 2022;28(7):1345-1347. doi:10.1038/s41591-022-01881-5

- Koczkodaj P, Sulkowska U, Didkowska J, et al. Melanoma mortality trends in 28 European countries: a retrospective analysis for the years 1960-2020. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(5):1514. Published 2023 Feb 28. doi:10.3390/cancers15051514

- Okobi OE, Abreo E, Sams NP, et al. Trends in melanoma incidence, prevalence, stage at diagnosis, and survival: an analysis of the United States Cancer Statistics (USCS) database. Cureus. 2024;16(10):e70697. doi:10.7759/cureus.70697

- Bartling SJ, Rivard SC, Meyerle JH. Melanoma in an active duty marine. Mil Med. 2017;182:e2034-e2039. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-17-00127

- American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2023. American Cancer Society; 2023. Accessed June 20, 2025. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2023/2023-cancer-facts-and-figures.pdf

- Rezaei SJ, Kim J, Onyeka S, et al. Skin cancer and other dermatologic conditions among US veterans. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160(10):1107-1111. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2024.3043

- Chang MS, La J, Trepanowski N, et al. Increased relative proportions of advanced melanoma among veterans: a comparative analysis with the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:72-79. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.02.063

- Riemenschneider K, Liu J, Powers JG. Skin cancer in the military: a systematic review of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer incidence, prevention, and screening among active duty and veteran personnel. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1185-1192. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.062

- Huang FW, Hodis E, Xu MJ, et al. Highly recurrent TERT promoter mutations in human melanoma. Science. 2013;339:957-959. doi:10.1126/science.1229259

- Tate JG, Bamford S, Jubb HC, et al. COSMIC: the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D941-D947. doi:10.1093/nar/gky1015

- Li M, Gao X, Wang X. Identification of tumor mutation burden-associated molecular and clinical features in cancer by analyzing multi-omics data. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1090838. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1090838

- Bonneville R, Krook MA, Kautto EA, et al. Landscape of microsatellite instability across 39 cancer types. JCO Precis Oncol. 2017;2017:PO.17.00073. doi:10.1200/PO.17.00073

- Lui AJ, Pagadala MS, Zhong AY, et al. Agent Orange exposure and prostate cancer risk in the Million Veteran Program. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2023:2023.06.14.23291413. doi:10.1101/2023.06.14.23291413

- Davis EJ, Johnson DB, Sosman JA, et al. Melanoma: what do all the mutations mean? Cancer. 2018;124:3490-3499. doi:10.1002/cncr.31345

- Guo Y, Chen Y, Zhang L, et al. TERT promoter mutations and telomerase in melanoma. J Oncol. 2022;2022:6300329. doi:10.1155/2022/6300329

- Whiteman DC, Stickley M, Watt P, et al. Anatomic site, sun exposure, and risk of cutaneous melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3172-3177. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.06.1325

- Decatur CL, Ong E, Garg N, et al. Driver mutations in uveal melanoma: associations with gene expression profile and patient outcomes. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134:728-733. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.0903

- Gutiérrez-Castañeda LD, Nova JA, Tovar-Parra JD. Frequency of mutations in BRAF, NRAS, and KIT in different populations and histological subtypes of melanoma: a systemic review. Melanoma Res. 2020;30:62- 70. doi:10.1097/CMR.0000000000000628

- Thielmann CM, Chorti E, Matull J, et al. NF1-mutated melanomas reveal distinct clinical characteristics depending on tumour origin and respond favourably to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Eur J Cancer. 2021;159:113-124. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2021.09.035

- D’Ecclesiis O, Caini S, Martinoli C, et al. Gender-dependent specificities in cutaneous melanoma predisposition, risk factors, somatic mutations, prognostic and predictive factors: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:7945. doi:10.3390/ijerph18157945

- Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Genomic classification of cutaneous melanoma. Cell. 2015;161:1681-1696. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.044

- Yu Z, Wang J, Feng L, et al. Association of tumor mutational burden with age in solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:e13590-e13590. doi:10.1200/JCO.2020.38.15_suppl.e13590

The veteran population, with its unique and diverse types of exposure and military service experiences, faces distinct health factors compared with the general population. These factors can be categorized into exposures during military service and those occurring postservice. While the latter phase incorporates psychological issues that may arise while transitioning to civilian life, the service period is associated with major physical, chemical, and psychological exposures that can impact veterans’ health. Carcinogenesis related to military exposures is concerning, and different types of malignancies have been associated with military exposures.1 The 2022 introduction of the Cancer Moonshot initiative served as a breeding ground for multiple projects aimed at investigation of exposure-related carcinogenesis, prompting increased attention and efforts to linking specific exposures to specific malignancies.2

Melanoma is the deadliest skin cancer, accounting for 1.3% of all cancer deaths.3 Although it may only account for 1% to 5% of skin cancer diagnoses, its incidence in the United States’ population has been increasing.4,5 There were 97,610 estimated new cases of melanoma in 2023, according to the National Cancer Institute.6

The incidence of melanoma may be higher in the military population compared with the general population.7 Melanoma is the fourth-most common cancer diagnosed in veterans.8

Several demographic characteristics of the US military population are associated with higher melanoma incidence and poorer prognosis, including male sex, older age, and White race. Apart from sun exposure—a known risk factor for melanoma development—other factors, such as service branch, seem to contribute to risk, with the highest melanoma rates noted in the Air Force.9 According to a study by Chang et al, veterans have a higher risk of stage III (18%) or stage IV (13%) melanoma at initial diagnosis.8

Molecular testing of metastatic melanoma is currently the standard of care for guiding the use of US Food and Drug Administration-approved targeted therapies such as BRAF, MEK, and KIT inhibitors. This comparative analysis details the melanoma comprehensive genomic profiles observed at a large US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center (VAMC) and those reported in reference databases.

Methods

A query to select all metastatic melanomas sent for comprehensive genomic profiling from the Kansas City VAMC (KCVAMC), identified 35 cases from 2019 through 2023 as the study population. The health records of these patients were reviewed to collect demographic information, military service history, melanoma history, other medical, social, and family histories. The comprehensive genomic profiling reports were reviewed to collect the reported pathogenic variants, microsatellite instability (MSI) status, and tumor mutational burden (TMB) for each case.

The Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) was used to identify the most commonly mutated genes in melanomas from The Cancer Genome Atlas for the general population.4,5 The literature was consulted to determine the MSI status and TMB in melanomas from The Cancer Genome Atlas for separate reference populations.6,7 The frequency of MSI-high (MSI-H) status, TMB ≥ 10 mutations/megabase (mut/Mb), and mutations in each of the 20 most commonly mutated genes was determined and compared between melanomas from The Cancer Genome Atlas and KCVAMC cases. Corresponding P values were calculated to identify significant differences. Values were calculated for the entire sample as well as a subgroup with Agent Orange (AO) exposure. The study was approved by the KCVAMC Institutional Review Board.

Results

The mean (SD) age of study participants was 72.9 (9.4) years (range, 39-90 years). The mean (SD) duration of military service was 1654 (1421) days (about 4 years, 6 months, and 10 days). Of the 35 patients included, 22 (63%) served during the Vietnam era (November 1, 1965, to April 30, 1975) and 2 (6%) served during the Persian Gulf War era (August 2, 1990, to February 28, 1991). Seventeen veterans (49%) served in the Army, 9 in the Navy (26%), 5 in the Air Force (14%), and 4 in the Marine Corps (11%). Definitive AO exposure was noted in 13 patients (37%) (Table 1).

Of the 35 patients, 24 (69%) had metastatic disease and the primary site of melanoma was unknown in 14 patients (40%). One patient (Patient 32) had an intraocular melanoma. The primary site was the trunk for 11 patients (31%), the face/head for 7 patients (20%) and extremities for 3 patients (9%). Eight patients (23%) were pT3 stage (thickness > 2 mm but < 4 mm), 7 patients (20%) were pT4 stage (thickness > 4 mm), and 5 patients (14%) were pT1 (thickness ≥ 1 mm). One patient had a primary lesion at pT2 stage, and 1 had a Tis stage lesion. Three patients (9%) had a family history of melanoma in a first-degree relative.

The list of genes mutated in melanoma cells in the study population is provided in the eAppendix.10,11 Twenty-seven patients (77%) had mutations in TERT promoter, 15 (43%) in CDKN2A/B, 13 (37%) in BRAF, 11 (31%) in NF1, 9 (26%) in TP53, and 8 (23%) in NRAS (Table 2). The majority of mutations in TERT promoter were c.- 146C>T (18 of 27 patients [67%]), whereas c.-124C>T was the second-most common (8 of 27 patients [30%]). The 2 observed mutations in the 13 patients with BRAF mutations were V600E and V600K, with almost equal distribution (54% and 46%, respectively). The mean (SD) TMB was 33.2 (39) mut/Mb (range, 1-203 mut/Mb). Ten patients (29%) had a TMB < 10 mut/Mb, whereas 24 (69%) had a TMB > 10 mut/Mb. The TMB could not be determined in 1 case. The frequency of TMB-high tumors in the study population compared with frequency in the reference population is shown in Table 3.12 Only 3 patients (0.64%) in the reference population had MSI-H tumors, and the microsatellite status could not be determined in those tumors (Table 4).13 Table 5 outlines statistically significant findings.

Agent Orange Subgroup

AO was a tactical herbicide used by the US military, named for the orange band around the storage barrels. Possible mutagenic properties of AO have been attributed to its byproduct, dioxin. Among the most common cancers known to be associated with AO exposure are bladder and prostate carcinoma and hematopoietic neoplasms. The association between genetic alterations and AO exposure was studied in veterans with prostate cancer.14 However, to our knowledge, insufficient information is available to determine whether an association exists between exposure to herbicides used in Vietnam or the contaminant dioxin and melanoma. Because a significant proportion of this study population had a well-documented history of AO exposure (37.1%), we were able to analyze them as a subgroup and to separately compare their mutation frequency with the general population.

Results were notable for different distributions of the most frequently mutated genes in the AO subgroup compared with the whole study population. As such, TERT promoter remained the most frequently mutated gene (92%), followed by CDKN2A/B (46%); however, frequency of mutations in NF1 (46%) outnumbered those of BRAF (31%), the fourth-most common mutation. Moreover, when compared with the general melanoma population, a significantly higher frequency of mutations in the NF1 gene was observed in the AO subgroup—not the entire study population.

Discussion

Given that veterans constitute a distinct population, there is reasonable interest in investigating characteristic health issues related to military service. Skin cancer—melanoma in particular—has been researched recently in a veteran population. The differences in demographics, tumor characteristics, and melanoma- specific survival in veterans compared with the general population have already been assessed. According to Chang et al, compared with the general population, veterans are more likely to present with metastatic disease and have lower 5-year survival rates.8

Melanoma is one of the most highly mutated malignancies.15 Fortunately, the most common mutation in melanoma, BRAF V600E, is now considered therapeutically targetable. However, there are still many mutations that are less often discussed and not well understood. Regardless of therapeutic implications, all mutations observed in melanoma are worth investigating because a tumor’s genomic profile also can provide prognostic and etiologic information. Developing comprehensive descriptions of melanoma mutational profiles in specific populations is critical to advancing etiologic understanding and informing prevention strategies.

Our results demonstrate the high prevalence of TERT promoter mutations with characteristic ultraviolet signature (C>T) in the study population. This aligns with general evidence that TERT promoter mutations are common in cutaneous melanomas: 77% of this study sample and up to 86% of all mutations are TERT promoter mutations, according to Davis et al.15 TERT promoter mutations are positively associated with the initiation, invasion, and metastasis of melanoma. In certain subtypes, there is evidence that the presence of TERT promoter mutations is significantly associated with risk for extranodal metastasis and death.16 The second-most common mutated gene in the veteran study population was CDKN2A/B (43%), and the third-most mutated gene was BRAF (37%).

In chronically sun-exposed skin NF1, NRAS, and occasionally BRAF V600K mutations tend to predominate. BRAF V600E mutations, on the other hand, are rare in these melanomas.15 In our study population, the most prevalent melanoma site was the trunk (31%), which is considered a location with an intermittent pattern of sun exposure.17

This study population also had a higher frequency of CDKN2A/B mutations. High frequencies of CDKN2A/B mutations have been reported in familial melanomas, but only 1 patient with CDKN2A/B mutations had a known family history of melanoma.15 Tumors in the study population showed significantly lower frequency of mutations in ROS1, GRIN2A, KDR, KMT2C (MLL3), KMT2D (MLL2), LRP1B, PTPRT, PTCH1, FAT4, and PREX2 (P < .05).

In this study the subgroup of veterans with AO exposure differed from the whole study population. As such, CDKN2A/B mutations were observed with the same frequency as NF1 mutations (46% each); however, BRAF mutations constituted only 31% of the mutations. In addition, the frequency of NF1 mutations was significantly higher in the AO subgroup compared with the general population, but not in the whole study population.

Our sample also differed from the reference population by showing a significantly higher frequency of TMB-high (ie, ≥ 10 mut/Mb) tumors (71% vs 49%; P = .01).12 Interestingly, no significant difference in the frequency of TMB-high tumors was observed between the AO subgroup and the reference population (69% vs 49%; P = .16). There also was no statistically significant difference between the frequency of MSI-H tumors in our study population and the reference population (P = .64).13

One patient in the study population had uveal melanoma. Mutations encountered in this patient’s tumor differed from the general mutational profile of tumors. None of the 21 mutations depicted in Table 2 were present in this sample.10,11 On the other hand, those mutations frequently observed in intraocular melanomas, BAP1 and GNA11, were present in this patient.18 Additionally, this particular melanoma possessed mutations in genes RICTOR, RAD21, and PIK3R1.

Limitations

This study population consisted exclusively of male patients, introducing sex as a potential confounder in analyzing differences between the study population and the general population. As noted in a 2020 systematic review, there were no sex-based differences in the frequency of mutations in BRAF, NRAS, and KIT genes.19

Regarding NF1 mutations, only NF1-mutated acral and mucosal melanomas were more frequently observed in female patients, whereas nonacral NF1-mutated melanomas were more frequently observed in male patients.20 However, there is currently no clear evidence of whether the mutational landscapes of cutaneous melanoma differ by sex.21 Among the 11 cases with NF1-mutatation, site of origin was known in 6, 5 of which originated at nonacral sites. Although the AO subgroup also consisted entirely of male patients, this does not explain the observed increased frequency of NF1 mutations relative to the general population. No such difference was observed between the whole study population, which also consisted exclusively of male patients, and the general population. The similar frequencies of nonacral location in the whole study population (3 acral, 18 nonacral, 14 unknown site of origin) and AO subgroup (1 acral, 7 nonacral, 5 unknown site of origin) preclude location as an explanation.

The Cancer Genome Atlas Network proposed a framework for genomic classification of melanoma into 4 subtypes based on the pattern of the most prevalent significantly mutated genes: mutant BRAF, mutant RAS, mutant NF1, and triple–wild-type. According to that study, BRAF mutations were indeed associated with younger age, in contrast to the NF1-mutant genomic subtype, which was more prevalent in older individuals with higher TMB.22 This emphasizes the need to interpret the potential association of AO exposure and NF1 mutation in melanoma with caution, although additional studies are required to observe the difference between the veteran population and age-matched general population.

On the other hand, Yu et al reported no significant differences of TMB values between patients aged < 60 and ≥ 60 years with melanoma.23 In short, the observed differences we report in our limited study warrant additional investigation with larger sample sizes, sex-matched controlling, and age-matched controlling. The study was limited by its small sample size and the single location.

Conclusion

The genomic profile of melanomas in the veteran population appears to be similar to that of the general population with a few possible differences. Melanomas in the veteran study population showed a higher frequency of CDKN2A/B mutations; lower frequency of ROS1, GRIN2A, KDR, KMT2C (MLL3), KMT2D (MLL2), LRP1B, PTPRT, PTCH1, FAT4, and PREX2 mutations; and higher TMB. In addition, melanomas in the AO subgroup showed higher frequencies of NF1 mutations. The significance of such findings remains to be determined by further investigation.

The veteran population, with its unique and diverse types of exposure and military service experiences, faces distinct health factors compared with the general population. These factors can be categorized into exposures during military service and those occurring postservice. While the latter phase incorporates psychological issues that may arise while transitioning to civilian life, the service period is associated with major physical, chemical, and psychological exposures that can impact veterans’ health. Carcinogenesis related to military exposures is concerning, and different types of malignancies have been associated with military exposures.1 The 2022 introduction of the Cancer Moonshot initiative served as a breeding ground for multiple projects aimed at investigation of exposure-related carcinogenesis, prompting increased attention and efforts to linking specific exposures to specific malignancies.2

Melanoma is the deadliest skin cancer, accounting for 1.3% of all cancer deaths.3 Although it may only account for 1% to 5% of skin cancer diagnoses, its incidence in the United States’ population has been increasing.4,5 There were 97,610 estimated new cases of melanoma in 2023, according to the National Cancer Institute.6

The incidence of melanoma may be higher in the military population compared with the general population.7 Melanoma is the fourth-most common cancer diagnosed in veterans.8

Several demographic characteristics of the US military population are associated with higher melanoma incidence and poorer prognosis, including male sex, older age, and White race. Apart from sun exposure—a known risk factor for melanoma development—other factors, such as service branch, seem to contribute to risk, with the highest melanoma rates noted in the Air Force.9 According to a study by Chang et al, veterans have a higher risk of stage III (18%) or stage IV (13%) melanoma at initial diagnosis.8

Molecular testing of metastatic melanoma is currently the standard of care for guiding the use of US Food and Drug Administration-approved targeted therapies such as BRAF, MEK, and KIT inhibitors. This comparative analysis details the melanoma comprehensive genomic profiles observed at a large US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center (VAMC) and those reported in reference databases.

Methods

A query to select all metastatic melanomas sent for comprehensive genomic profiling from the Kansas City VAMC (KCVAMC), identified 35 cases from 2019 through 2023 as the study population. The health records of these patients were reviewed to collect demographic information, military service history, melanoma history, other medical, social, and family histories. The comprehensive genomic profiling reports were reviewed to collect the reported pathogenic variants, microsatellite instability (MSI) status, and tumor mutational burden (TMB) for each case.

The Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) was used to identify the most commonly mutated genes in melanomas from The Cancer Genome Atlas for the general population.4,5 The literature was consulted to determine the MSI status and TMB in melanomas from The Cancer Genome Atlas for separate reference populations.6,7 The frequency of MSI-high (MSI-H) status, TMB ≥ 10 mutations/megabase (mut/Mb), and mutations in each of the 20 most commonly mutated genes was determined and compared between melanomas from The Cancer Genome Atlas and KCVAMC cases. Corresponding P values were calculated to identify significant differences. Values were calculated for the entire sample as well as a subgroup with Agent Orange (AO) exposure. The study was approved by the KCVAMC Institutional Review Board.

Results

The mean (SD) age of study participants was 72.9 (9.4) years (range, 39-90 years). The mean (SD) duration of military service was 1654 (1421) days (about 4 years, 6 months, and 10 days). Of the 35 patients included, 22 (63%) served during the Vietnam era (November 1, 1965, to April 30, 1975) and 2 (6%) served during the Persian Gulf War era (August 2, 1990, to February 28, 1991). Seventeen veterans (49%) served in the Army, 9 in the Navy (26%), 5 in the Air Force (14%), and 4 in the Marine Corps (11%). Definitive AO exposure was noted in 13 patients (37%) (Table 1).

Of the 35 patients, 24 (69%) had metastatic disease and the primary site of melanoma was unknown in 14 patients (40%). One patient (Patient 32) had an intraocular melanoma. The primary site was the trunk for 11 patients (31%), the face/head for 7 patients (20%) and extremities for 3 patients (9%). Eight patients (23%) were pT3 stage (thickness > 2 mm but < 4 mm), 7 patients (20%) were pT4 stage (thickness > 4 mm), and 5 patients (14%) were pT1 (thickness ≥ 1 mm). One patient had a primary lesion at pT2 stage, and 1 had a Tis stage lesion. Three patients (9%) had a family history of melanoma in a first-degree relative.

The list of genes mutated in melanoma cells in the study population is provided in the eAppendix.10,11 Twenty-seven patients (77%) had mutations in TERT promoter, 15 (43%) in CDKN2A/B, 13 (37%) in BRAF, 11 (31%) in NF1, 9 (26%) in TP53, and 8 (23%) in NRAS (Table 2). The majority of mutations in TERT promoter were c.- 146C>T (18 of 27 patients [67%]), whereas c.-124C>T was the second-most common (8 of 27 patients [30%]). The 2 observed mutations in the 13 patients with BRAF mutations were V600E and V600K, with almost equal distribution (54% and 46%, respectively). The mean (SD) TMB was 33.2 (39) mut/Mb (range, 1-203 mut/Mb). Ten patients (29%) had a TMB < 10 mut/Mb, whereas 24 (69%) had a TMB > 10 mut/Mb. The TMB could not be determined in 1 case. The frequency of TMB-high tumors in the study population compared with frequency in the reference population is shown in Table 3.12 Only 3 patients (0.64%) in the reference population had MSI-H tumors, and the microsatellite status could not be determined in those tumors (Table 4).13 Table 5 outlines statistically significant findings.

Agent Orange Subgroup

AO was a tactical herbicide used by the US military, named for the orange band around the storage barrels. Possible mutagenic properties of AO have been attributed to its byproduct, dioxin. Among the most common cancers known to be associated with AO exposure are bladder and prostate carcinoma and hematopoietic neoplasms. The association between genetic alterations and AO exposure was studied in veterans with prostate cancer.14 However, to our knowledge, insufficient information is available to determine whether an association exists between exposure to herbicides used in Vietnam or the contaminant dioxin and melanoma. Because a significant proportion of this study population had a well-documented history of AO exposure (37.1%), we were able to analyze them as a subgroup and to separately compare their mutation frequency with the general population.

Results were notable for different distributions of the most frequently mutated genes in the AO subgroup compared with the whole study population. As such, TERT promoter remained the most frequently mutated gene (92%), followed by CDKN2A/B (46%); however, frequency of mutations in NF1 (46%) outnumbered those of BRAF (31%), the fourth-most common mutation. Moreover, when compared with the general melanoma population, a significantly higher frequency of mutations in the NF1 gene was observed in the AO subgroup—not the entire study population.

Discussion

Given that veterans constitute a distinct population, there is reasonable interest in investigating characteristic health issues related to military service. Skin cancer—melanoma in particular—has been researched recently in a veteran population. The differences in demographics, tumor characteristics, and melanoma- specific survival in veterans compared with the general population have already been assessed. According to Chang et al, compared with the general population, veterans are more likely to present with metastatic disease and have lower 5-year survival rates.8

Melanoma is one of the most highly mutated malignancies.15 Fortunately, the most common mutation in melanoma, BRAF V600E, is now considered therapeutically targetable. However, there are still many mutations that are less often discussed and not well understood. Regardless of therapeutic implications, all mutations observed in melanoma are worth investigating because a tumor’s genomic profile also can provide prognostic and etiologic information. Developing comprehensive descriptions of melanoma mutational profiles in specific populations is critical to advancing etiologic understanding and informing prevention strategies.

Our results demonstrate the high prevalence of TERT promoter mutations with characteristic ultraviolet signature (C>T) in the study population. This aligns with general evidence that TERT promoter mutations are common in cutaneous melanomas: 77% of this study sample and up to 86% of all mutations are TERT promoter mutations, according to Davis et al.15 TERT promoter mutations are positively associated with the initiation, invasion, and metastasis of melanoma. In certain subtypes, there is evidence that the presence of TERT promoter mutations is significantly associated with risk for extranodal metastasis and death.16 The second-most common mutated gene in the veteran study population was CDKN2A/B (43%), and the third-most mutated gene was BRAF (37%).

In chronically sun-exposed skin NF1, NRAS, and occasionally BRAF V600K mutations tend to predominate. BRAF V600E mutations, on the other hand, are rare in these melanomas.15 In our study population, the most prevalent melanoma site was the trunk (31%), which is considered a location with an intermittent pattern of sun exposure.17

This study population also had a higher frequency of CDKN2A/B mutations. High frequencies of CDKN2A/B mutations have been reported in familial melanomas, but only 1 patient with CDKN2A/B mutations had a known family history of melanoma.15 Tumors in the study population showed significantly lower frequency of mutations in ROS1, GRIN2A, KDR, KMT2C (MLL3), KMT2D (MLL2), LRP1B, PTPRT, PTCH1, FAT4, and PREX2 (P < .05).

In this study the subgroup of veterans with AO exposure differed from the whole study population. As such, CDKN2A/B mutations were observed with the same frequency as NF1 mutations (46% each); however, BRAF mutations constituted only 31% of the mutations. In addition, the frequency of NF1 mutations was significantly higher in the AO subgroup compared with the general population, but not in the whole study population.

Our sample also differed from the reference population by showing a significantly higher frequency of TMB-high (ie, ≥ 10 mut/Mb) tumors (71% vs 49%; P = .01).12 Interestingly, no significant difference in the frequency of TMB-high tumors was observed between the AO subgroup and the reference population (69% vs 49%; P = .16). There also was no statistically significant difference between the frequency of MSI-H tumors in our study population and the reference population (P = .64).13

One patient in the study population had uveal melanoma. Mutations encountered in this patient’s tumor differed from the general mutational profile of tumors. None of the 21 mutations depicted in Table 2 were present in this sample.10,11 On the other hand, those mutations frequently observed in intraocular melanomas, BAP1 and GNA11, were present in this patient.18 Additionally, this particular melanoma possessed mutations in genes RICTOR, RAD21, and PIK3R1.

Limitations

This study population consisted exclusively of male patients, introducing sex as a potential confounder in analyzing differences between the study population and the general population. As noted in a 2020 systematic review, there were no sex-based differences in the frequency of mutations in BRAF, NRAS, and KIT genes.19

Regarding NF1 mutations, only NF1-mutated acral and mucosal melanomas were more frequently observed in female patients, whereas nonacral NF1-mutated melanomas were more frequently observed in male patients.20 However, there is currently no clear evidence of whether the mutational landscapes of cutaneous melanoma differ by sex.21 Among the 11 cases with NF1-mutatation, site of origin was known in 6, 5 of which originated at nonacral sites. Although the AO subgroup also consisted entirely of male patients, this does not explain the observed increased frequency of NF1 mutations relative to the general population. No such difference was observed between the whole study population, which also consisted exclusively of male patients, and the general population. The similar frequencies of nonacral location in the whole study population (3 acral, 18 nonacral, 14 unknown site of origin) and AO subgroup (1 acral, 7 nonacral, 5 unknown site of origin) preclude location as an explanation.

The Cancer Genome Atlas Network proposed a framework for genomic classification of melanoma into 4 subtypes based on the pattern of the most prevalent significantly mutated genes: mutant BRAF, mutant RAS, mutant NF1, and triple–wild-type. According to that study, BRAF mutations were indeed associated with younger age, in contrast to the NF1-mutant genomic subtype, which was more prevalent in older individuals with higher TMB.22 This emphasizes the need to interpret the potential association of AO exposure and NF1 mutation in melanoma with caution, although additional studies are required to observe the difference between the veteran population and age-matched general population.

On the other hand, Yu et al reported no significant differences of TMB values between patients aged < 60 and ≥ 60 years with melanoma.23 In short, the observed differences we report in our limited study warrant additional investigation with larger sample sizes, sex-matched controlling, and age-matched controlling. The study was limited by its small sample size and the single location.

Conclusion

The genomic profile of melanomas in the veteran population appears to be similar to that of the general population with a few possible differences. Melanomas in the veteran study population showed a higher frequency of CDKN2A/B mutations; lower frequency of ROS1, GRIN2A, KDR, KMT2C (MLL3), KMT2D (MLL2), LRP1B, PTPRT, PTCH1, FAT4, and PREX2 mutations; and higher TMB. In addition, melanomas in the AO subgroup showed higher frequencies of NF1 mutations. The significance of such findings remains to be determined by further investigation.

- Bytnar JA, McGlynn KA, et al. Cancer incidence in the US military: An updated analysis. Cancer. 2024;130(1):96-106. doi:10.1002/cncr.34978

- Singer DS. A new phase of the Cancer Moonshot to end cancer as we know it. Nat Med. 2022;28(7):1345-1347. doi:10.1038/s41591-022-01881-5

- Koczkodaj P, Sulkowska U, Didkowska J, et al. Melanoma mortality trends in 28 European countries: a retrospective analysis for the years 1960-2020. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(5):1514. Published 2023 Feb 28. doi:10.3390/cancers15051514

- Okobi OE, Abreo E, Sams NP, et al. Trends in melanoma incidence, prevalence, stage at diagnosis, and survival: an analysis of the United States Cancer Statistics (USCS) database. Cureus. 2024;16(10):e70697. doi:10.7759/cureus.70697

- Bartling SJ, Rivard SC, Meyerle JH. Melanoma in an active duty marine. Mil Med. 2017;182:e2034-e2039. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-17-00127

- American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2023. American Cancer Society; 2023. Accessed June 20, 2025. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2023/2023-cancer-facts-and-figures.pdf

- Rezaei SJ, Kim J, Onyeka S, et al. Skin cancer and other dermatologic conditions among US veterans. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160(10):1107-1111. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2024.3043

- Chang MS, La J, Trepanowski N, et al. Increased relative proportions of advanced melanoma among veterans: a comparative analysis with the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:72-79. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.02.063

- Riemenschneider K, Liu J, Powers JG. Skin cancer in the military: a systematic review of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer incidence, prevention, and screening among active duty and veteran personnel. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1185-1192. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.062

- Huang FW, Hodis E, Xu MJ, et al. Highly recurrent TERT promoter mutations in human melanoma. Science. 2013;339:957-959. doi:10.1126/science.1229259

- Tate JG, Bamford S, Jubb HC, et al. COSMIC: the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D941-D947. doi:10.1093/nar/gky1015

- Li M, Gao X, Wang X. Identification of tumor mutation burden-associated molecular and clinical features in cancer by analyzing multi-omics data. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1090838. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1090838

- Bonneville R, Krook MA, Kautto EA, et al. Landscape of microsatellite instability across 39 cancer types. JCO Precis Oncol. 2017;2017:PO.17.00073. doi:10.1200/PO.17.00073

- Lui AJ, Pagadala MS, Zhong AY, et al. Agent Orange exposure and prostate cancer risk in the Million Veteran Program. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2023:2023.06.14.23291413. doi:10.1101/2023.06.14.23291413

- Davis EJ, Johnson DB, Sosman JA, et al. Melanoma: what do all the mutations mean? Cancer. 2018;124:3490-3499. doi:10.1002/cncr.31345

- Guo Y, Chen Y, Zhang L, et al. TERT promoter mutations and telomerase in melanoma. J Oncol. 2022;2022:6300329. doi:10.1155/2022/6300329

- Whiteman DC, Stickley M, Watt P, et al. Anatomic site, sun exposure, and risk of cutaneous melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3172-3177. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.06.1325

- Decatur CL, Ong E, Garg N, et al. Driver mutations in uveal melanoma: associations with gene expression profile and patient outcomes. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134:728-733. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.0903

- Gutiérrez-Castañeda LD, Nova JA, Tovar-Parra JD. Frequency of mutations in BRAF, NRAS, and KIT in different populations and histological subtypes of melanoma: a systemic review. Melanoma Res. 2020;30:62- 70. doi:10.1097/CMR.0000000000000628

- Thielmann CM, Chorti E, Matull J, et al. NF1-mutated melanomas reveal distinct clinical characteristics depending on tumour origin and respond favourably to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Eur J Cancer. 2021;159:113-124. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2021.09.035

- D’Ecclesiis O, Caini S, Martinoli C, et al. Gender-dependent specificities in cutaneous melanoma predisposition, risk factors, somatic mutations, prognostic and predictive factors: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:7945. doi:10.3390/ijerph18157945

- Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Genomic classification of cutaneous melanoma. Cell. 2015;161:1681-1696. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.044

- Yu Z, Wang J, Feng L, et al. Association of tumor mutational burden with age in solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:e13590-e13590. doi:10.1200/JCO.2020.38.15_suppl.e13590

- Bytnar JA, McGlynn KA, et al. Cancer incidence in the US military: An updated analysis. Cancer. 2024;130(1):96-106. doi:10.1002/cncr.34978

- Singer DS. A new phase of the Cancer Moonshot to end cancer as we know it. Nat Med. 2022;28(7):1345-1347. doi:10.1038/s41591-022-01881-5

- Koczkodaj P, Sulkowska U, Didkowska J, et al. Melanoma mortality trends in 28 European countries: a retrospective analysis for the years 1960-2020. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(5):1514. Published 2023 Feb 28. doi:10.3390/cancers15051514

- Okobi OE, Abreo E, Sams NP, et al. Trends in melanoma incidence, prevalence, stage at diagnosis, and survival: an analysis of the United States Cancer Statistics (USCS) database. Cureus. 2024;16(10):e70697. doi:10.7759/cureus.70697

- Bartling SJ, Rivard SC, Meyerle JH. Melanoma in an active duty marine. Mil Med. 2017;182:e2034-e2039. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-17-00127

- American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2023. American Cancer Society; 2023. Accessed June 20, 2025. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2023/2023-cancer-facts-and-figures.pdf

- Rezaei SJ, Kim J, Onyeka S, et al. Skin cancer and other dermatologic conditions among US veterans. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160(10):1107-1111. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2024.3043

- Chang MS, La J, Trepanowski N, et al. Increased relative proportions of advanced melanoma among veterans: a comparative analysis with the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:72-79. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.02.063

- Riemenschneider K, Liu J, Powers JG. Skin cancer in the military: a systematic review of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer incidence, prevention, and screening among active duty and veteran personnel. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1185-1192. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.062

- Huang FW, Hodis E, Xu MJ, et al. Highly recurrent TERT promoter mutations in human melanoma. Science. 2013;339:957-959. doi:10.1126/science.1229259

- Tate JG, Bamford S, Jubb HC, et al. COSMIC: the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D941-D947. doi:10.1093/nar/gky1015

- Li M, Gao X, Wang X. Identification of tumor mutation burden-associated molecular and clinical features in cancer by analyzing multi-omics data. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1090838. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1090838

- Bonneville R, Krook MA, Kautto EA, et al. Landscape of microsatellite instability across 39 cancer types. JCO Precis Oncol. 2017;2017:PO.17.00073. doi:10.1200/PO.17.00073

- Lui AJ, Pagadala MS, Zhong AY, et al. Agent Orange exposure and prostate cancer risk in the Million Veteran Program. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2023:2023.06.14.23291413. doi:10.1101/2023.06.14.23291413

- Davis EJ, Johnson DB, Sosman JA, et al. Melanoma: what do all the mutations mean? Cancer. 2018;124:3490-3499. doi:10.1002/cncr.31345

- Guo Y, Chen Y, Zhang L, et al. TERT promoter mutations and telomerase in melanoma. J Oncol. 2022;2022:6300329. doi:10.1155/2022/6300329

- Whiteman DC, Stickley M, Watt P, et al. Anatomic site, sun exposure, and risk of cutaneous melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3172-3177. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.06.1325

- Decatur CL, Ong E, Garg N, et al. Driver mutations in uveal melanoma: associations with gene expression profile and patient outcomes. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134:728-733. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.0903

- Gutiérrez-Castañeda LD, Nova JA, Tovar-Parra JD. Frequency of mutations in BRAF, NRAS, and KIT in different populations and histological subtypes of melanoma: a systemic review. Melanoma Res. 2020;30:62- 70. doi:10.1097/CMR.0000000000000628

- Thielmann CM, Chorti E, Matull J, et al. NF1-mutated melanomas reveal distinct clinical characteristics depending on tumour origin and respond favourably to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Eur J Cancer. 2021;159:113-124. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2021.09.035

- D’Ecclesiis O, Caini S, Martinoli C, et al. Gender-dependent specificities in cutaneous melanoma predisposition, risk factors, somatic mutations, prognostic and predictive factors: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:7945. doi:10.3390/ijerph18157945

- Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Genomic classification of cutaneous melanoma. Cell. 2015;161:1681-1696. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.044

- Yu Z, Wang J, Feng L, et al. Association of tumor mutational burden with age in solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:e13590-e13590. doi:10.1200/JCO.2020.38.15_suppl.e13590

Comprehensive Genomic Profiles of Melanoma in Veterans Compared to Reference Databases

Comprehensive Genomic Profiles of Melanoma in Veterans Compared to Reference Databases

Does Ethnicity Affect Skin Cancer Risk?

Does Ethnicity Affect Skin Cancer Risk?

TOPLINE:

The incidence of skin cancer in England varied by ethnicity: White individuals had higher rates of melanoma, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, and basal cell carcinoma than Asian or Black individuals. In contrast, acral lentiginous melanoma was most common among Black individuals, whereas cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and Kaposi sarcoma were highest among those in the "Other" ethnic group.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers analysed all cases of cutaneous melanoma (melanoma and acral lentiginous melanoma), basal cell carcinoma, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and Kaposi sarcoma using data from the NHS National Disease Registration Service cancer registry between 2013 and 2020.

- Data collection incorporated ethnicity information from multiple health care datasets, including Clinical Outcomes and Services Dataset, Patient Administration System, Radiotherapy Dataset, Diagnostic Imaging Dataset, and Hospital Episode Statistics.

- A population analysis categorised patients into 7 standardised ethnic groups (on the basis of Office for National Statistics classifications): White, Asian, Chinese, Black, mixed, other, and unknown groups, with ethnicity data being self-reported by patients.

- Outcomes included European age-standardised rates calculated using the 2013 European Standard Population and reported per 100,000 person-years (PYs).

TAKEAWAY:

- White Individuals had 13-fold higher rates of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (61.75 per 100,000 PYs), 26-fold and 27-fold higher rates of basal cell carcinoma (153.69 per 100,000 PYs), and 33-fold and 16-fold higher rates of cutaneous melanoma (27.29 per 100,000 PYs) than Asian and Black individuals, respectively.

- Black individuals had the highest incidence of acral lentiginous melanoma (0.85 per 100,000 PYs), and those in the other ethnic group had the highest incidence of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (1.74 per 100,000 PYs) and Kaposi sarcoma (1.57 per 100,000 PYs).

- The presentation of early-stage melanoma was low among Asian (53.5%), Black (62.4%), mixed (62.5%), and other (76.4%) ethnic groups compared to that among White ethnicities (79.8%).

- Acral lentiginous melanomas were less likely to get urgent suspected cancer pathway referrals than overall melanoma (40.1% vs 44.6%; P < .001) and more likely to be diagnosed late than overall melanoma (stage I/II at diagnosis; 72% vs 80%; P < .0001).

IN PRACTICE:

"The findings emphasise the need for better, targeted ethnicity data collection strategies to address incidence, outcomes and health care equity for not just skin cancer but all health conditions in underserved populations," the authors wrote. "While projects like the Global Burden of Disease have improved global health care reporting, continuous audit and improvement of collected data are essential to provide better care across people of all ethnicities."

SOURCE:

This study was led by Shehnaz Ahmed, British Association of Dermatologists, London, England. It was published online on September 10, 2025, in the British Journal of Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Census data collection after every 10 years could have contributed to inaccurate population estimates and incidence rates. Small sample sizes in certain ethnic groups could have led to potential confounders, requiring a cautious interpretation of relative incidence. The NHS data included only self-reported ethnicity data with no available details of skin phototypes, skin tones, or racial ancestry. This study lacked granular ethnicity census data and stage data for basal cell carcinoma, cutaneous small cell carcinoma, and Kaposi sarcoma.

DISCLOSURES:

This research was supported through a partnership between the British Association of Dermatologists and NHS England's National Disease Registration Service. Two authors reported being employees of the British Association of Dermatologists.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

The incidence of skin cancer in England varied by ethnicity: White individuals had higher rates of melanoma, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, and basal cell carcinoma than Asian or Black individuals. In contrast, acral lentiginous melanoma was most common among Black individuals, whereas cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and Kaposi sarcoma were highest among those in the "Other" ethnic group.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers analysed all cases of cutaneous melanoma (melanoma and acral lentiginous melanoma), basal cell carcinoma, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and Kaposi sarcoma using data from the NHS National Disease Registration Service cancer registry between 2013 and 2020.

- Data collection incorporated ethnicity information from multiple health care datasets, including Clinical Outcomes and Services Dataset, Patient Administration System, Radiotherapy Dataset, Diagnostic Imaging Dataset, and Hospital Episode Statistics.

- A population analysis categorised patients into 7 standardised ethnic groups (on the basis of Office for National Statistics classifications): White, Asian, Chinese, Black, mixed, other, and unknown groups, with ethnicity data being self-reported by patients.

- Outcomes included European age-standardised rates calculated using the 2013 European Standard Population and reported per 100,000 person-years (PYs).

TAKEAWAY:

- White Individuals had 13-fold higher rates of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (61.75 per 100,000 PYs), 26-fold and 27-fold higher rates of basal cell carcinoma (153.69 per 100,000 PYs), and 33-fold and 16-fold higher rates of cutaneous melanoma (27.29 per 100,000 PYs) than Asian and Black individuals, respectively.

- Black individuals had the highest incidence of acral lentiginous melanoma (0.85 per 100,000 PYs), and those in the other ethnic group had the highest incidence of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (1.74 per 100,000 PYs) and Kaposi sarcoma (1.57 per 100,000 PYs).

- The presentation of early-stage melanoma was low among Asian (53.5%), Black (62.4%), mixed (62.5%), and other (76.4%) ethnic groups compared to that among White ethnicities (79.8%).

- Acral lentiginous melanomas were less likely to get urgent suspected cancer pathway referrals than overall melanoma (40.1% vs 44.6%; P < .001) and more likely to be diagnosed late than overall melanoma (stage I/II at diagnosis; 72% vs 80%; P < .0001).

IN PRACTICE:

"The findings emphasise the need for better, targeted ethnicity data collection strategies to address incidence, outcomes and health care equity for not just skin cancer but all health conditions in underserved populations," the authors wrote. "While projects like the Global Burden of Disease have improved global health care reporting, continuous audit and improvement of collected data are essential to provide better care across people of all ethnicities."

SOURCE:

This study was led by Shehnaz Ahmed, British Association of Dermatologists, London, England. It was published online on September 10, 2025, in the British Journal of Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Census data collection after every 10 years could have contributed to inaccurate population estimates and incidence rates. Small sample sizes in certain ethnic groups could have led to potential confounders, requiring a cautious interpretation of relative incidence. The NHS data included only self-reported ethnicity data with no available details of skin phototypes, skin tones, or racial ancestry. This study lacked granular ethnicity census data and stage data for basal cell carcinoma, cutaneous small cell carcinoma, and Kaposi sarcoma.

DISCLOSURES:

This research was supported through a partnership between the British Association of Dermatologists and NHS England's National Disease Registration Service. Two authors reported being employees of the British Association of Dermatologists.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

The incidence of skin cancer in England varied by ethnicity: White individuals had higher rates of melanoma, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, and basal cell carcinoma than Asian or Black individuals. In contrast, acral lentiginous melanoma was most common among Black individuals, whereas cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and Kaposi sarcoma were highest among those in the "Other" ethnic group.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers analysed all cases of cutaneous melanoma (melanoma and acral lentiginous melanoma), basal cell carcinoma, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and Kaposi sarcoma using data from the NHS National Disease Registration Service cancer registry between 2013 and 2020.

- Data collection incorporated ethnicity information from multiple health care datasets, including Clinical Outcomes and Services Dataset, Patient Administration System, Radiotherapy Dataset, Diagnostic Imaging Dataset, and Hospital Episode Statistics.

- A population analysis categorised patients into 7 standardised ethnic groups (on the basis of Office for National Statistics classifications): White, Asian, Chinese, Black, mixed, other, and unknown groups, with ethnicity data being self-reported by patients.

- Outcomes included European age-standardised rates calculated using the 2013 European Standard Population and reported per 100,000 person-years (PYs).

TAKEAWAY:

- White Individuals had 13-fold higher rates of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (61.75 per 100,000 PYs), 26-fold and 27-fold higher rates of basal cell carcinoma (153.69 per 100,000 PYs), and 33-fold and 16-fold higher rates of cutaneous melanoma (27.29 per 100,000 PYs) than Asian and Black individuals, respectively.

- Black individuals had the highest incidence of acral lentiginous melanoma (0.85 per 100,000 PYs), and those in the other ethnic group had the highest incidence of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (1.74 per 100,000 PYs) and Kaposi sarcoma (1.57 per 100,000 PYs).

- The presentation of early-stage melanoma was low among Asian (53.5%), Black (62.4%), mixed (62.5%), and other (76.4%) ethnic groups compared to that among White ethnicities (79.8%).

- Acral lentiginous melanomas were less likely to get urgent suspected cancer pathway referrals than overall melanoma (40.1% vs 44.6%; P < .001) and more likely to be diagnosed late than overall melanoma (stage I/II at diagnosis; 72% vs 80%; P < .0001).

IN PRACTICE:

"The findings emphasise the need for better, targeted ethnicity data collection strategies to address incidence, outcomes and health care equity for not just skin cancer but all health conditions in underserved populations," the authors wrote. "While projects like the Global Burden of Disease have improved global health care reporting, continuous audit and improvement of collected data are essential to provide better care across people of all ethnicities."

SOURCE:

This study was led by Shehnaz Ahmed, British Association of Dermatologists, London, England. It was published online on September 10, 2025, in the British Journal of Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Census data collection after every 10 years could have contributed to inaccurate population estimates and incidence rates. Small sample sizes in certain ethnic groups could have led to potential confounders, requiring a cautious interpretation of relative incidence. The NHS data included only self-reported ethnicity data with no available details of skin phototypes, skin tones, or racial ancestry. This study lacked granular ethnicity census data and stage data for basal cell carcinoma, cutaneous small cell carcinoma, and Kaposi sarcoma.

DISCLOSURES:

This research was supported through a partnership between the British Association of Dermatologists and NHS England's National Disease Registration Service. Two authors reported being employees of the British Association of Dermatologists.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Does Ethnicity Affect Skin Cancer Risk?

Does Ethnicity Affect Skin Cancer Risk?

Don’t Miss Those Blind Spots

Background

Choroidal malignant melanoma is a relatively rare condition, yet it remains the most common primary intraocular malignancy in adults, affecting approximately 5 individuals per million each year in the United States. Associated risk factors include fair skin, light-colored eyes, ocular melanocytosis, and BAP1 genetic mutations. While 13% of patients presenting with choroidal melanoma are asymptomatic, some symptoms can include photopsia, floaters, blurred vision, and progressive visual field loss.

Case Presentation

We present a case of choroidal melanoma in a 57-year-old male with a past medical history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, major depressive disorder, and alcohol use disorder. This patient presented to the clinic following a detoxification admission, reporting one week of progressive vision loss in the left eye. Upon initial physical examination, the patient exhibited left superior quadrantanopia, with a visual acuity of 20/40 measured in the left eye. Initial imaging with CT head identified an intraocular hyperdensity within the left globe, raising concerns for potential retinal detachment. Urgent ophthalmologic evaluation revealed an afferent pupillary defect and a large choroidal lesion adjacent to the optic nerve head. Ultrasonography showed a low internal reflectivity mass (5.36 mm by 9.05 mm), and a subsequent dilated fundus examination confirmed a classic dome-shaped choroidal melanoma (11.5 mm by 16.5 mm). Gene expression profiling demonstrated a class 1b uveal melanoma with PRAME positivity and mutations in GNAQ and SF3B1. Comprehensive staging scans were negative for metastatic disease. The patient received four treatment sessions of proton beam therapy, which resulted in rapid improvements in his visual fields. For long-term management, he was scheduled for close ophthalmologic follow-up and regular imaging of the chest and abdomen every six months to monitor for recurrence.

Conclusions

This case highlights the challenges of diagnosing choroidal melanoma in the primary care setting and the importance of multidisciplinary involvement, multimodal imaging, and gene expression profiling in facilitating early diagnosis and treatment.

Background

Choroidal malignant melanoma is a relatively rare condition, yet it remains the most common primary intraocular malignancy in adults, affecting approximately 5 individuals per million each year in the United States. Associated risk factors include fair skin, light-colored eyes, ocular melanocytosis, and BAP1 genetic mutations. While 13% of patients presenting with choroidal melanoma are asymptomatic, some symptoms can include photopsia, floaters, blurred vision, and progressive visual field loss.

Case Presentation

We present a case of choroidal melanoma in a 57-year-old male with a past medical history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, major depressive disorder, and alcohol use disorder. This patient presented to the clinic following a detoxification admission, reporting one week of progressive vision loss in the left eye. Upon initial physical examination, the patient exhibited left superior quadrantanopia, with a visual acuity of 20/40 measured in the left eye. Initial imaging with CT head identified an intraocular hyperdensity within the left globe, raising concerns for potential retinal detachment. Urgent ophthalmologic evaluation revealed an afferent pupillary defect and a large choroidal lesion adjacent to the optic nerve head. Ultrasonography showed a low internal reflectivity mass (5.36 mm by 9.05 mm), and a subsequent dilated fundus examination confirmed a classic dome-shaped choroidal melanoma (11.5 mm by 16.5 mm). Gene expression profiling demonstrated a class 1b uveal melanoma with PRAME positivity and mutations in GNAQ and SF3B1. Comprehensive staging scans were negative for metastatic disease. The patient received four treatment sessions of proton beam therapy, which resulted in rapid improvements in his visual fields. For long-term management, he was scheduled for close ophthalmologic follow-up and regular imaging of the chest and abdomen every six months to monitor for recurrence.

Conclusions

This case highlights the challenges of diagnosing choroidal melanoma in the primary care setting and the importance of multidisciplinary involvement, multimodal imaging, and gene expression profiling in facilitating early diagnosis and treatment.

Background

Choroidal malignant melanoma is a relatively rare condition, yet it remains the most common primary intraocular malignancy in adults, affecting approximately 5 individuals per million each year in the United States. Associated risk factors include fair skin, light-colored eyes, ocular melanocytosis, and BAP1 genetic mutations. While 13% of patients presenting with choroidal melanoma are asymptomatic, some symptoms can include photopsia, floaters, blurred vision, and progressive visual field loss.

Case Presentation

We present a case of choroidal melanoma in a 57-year-old male with a past medical history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, major depressive disorder, and alcohol use disorder. This patient presented to the clinic following a detoxification admission, reporting one week of progressive vision loss in the left eye. Upon initial physical examination, the patient exhibited left superior quadrantanopia, with a visual acuity of 20/40 measured in the left eye. Initial imaging with CT head identified an intraocular hyperdensity within the left globe, raising concerns for potential retinal detachment. Urgent ophthalmologic evaluation revealed an afferent pupillary defect and a large choroidal lesion adjacent to the optic nerve head. Ultrasonography showed a low internal reflectivity mass (5.36 mm by 9.05 mm), and a subsequent dilated fundus examination confirmed a classic dome-shaped choroidal melanoma (11.5 mm by 16.5 mm). Gene expression profiling demonstrated a class 1b uveal melanoma with PRAME positivity and mutations in GNAQ and SF3B1. Comprehensive staging scans were negative for metastatic disease. The patient received four treatment sessions of proton beam therapy, which resulted in rapid improvements in his visual fields. For long-term management, he was scheduled for close ophthalmologic follow-up and regular imaging of the chest and abdomen every six months to monitor for recurrence.

Conclusions

This case highlights the challenges of diagnosing choroidal melanoma in the primary care setting and the importance of multidisciplinary involvement, multimodal imaging, and gene expression profiling in facilitating early diagnosis and treatment.

Pigmented Cystic Masses on the Scalp

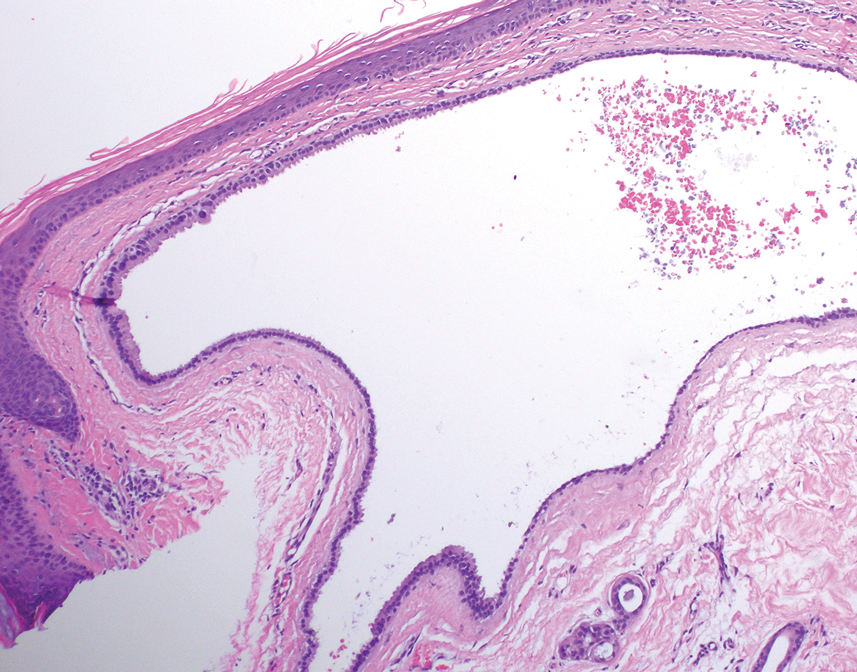

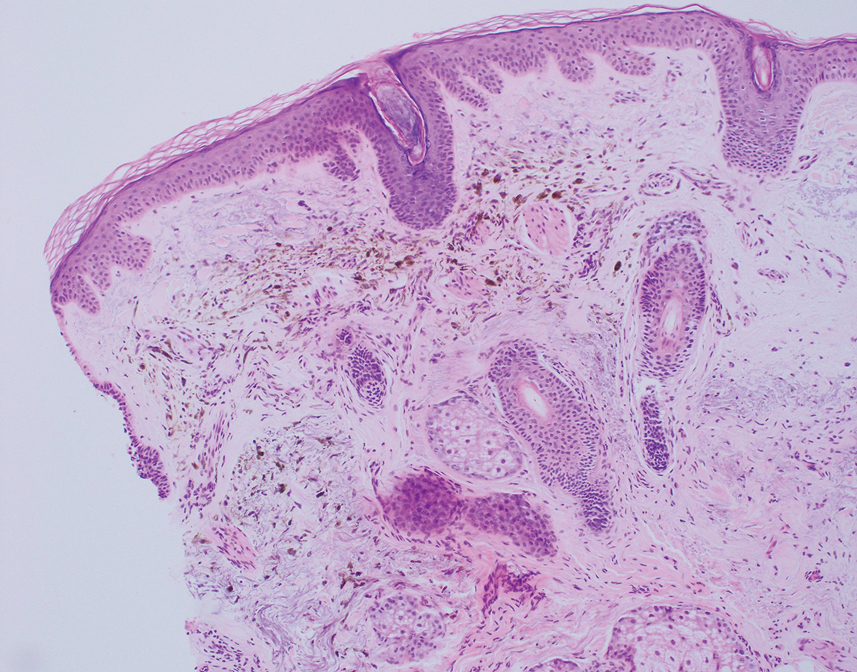

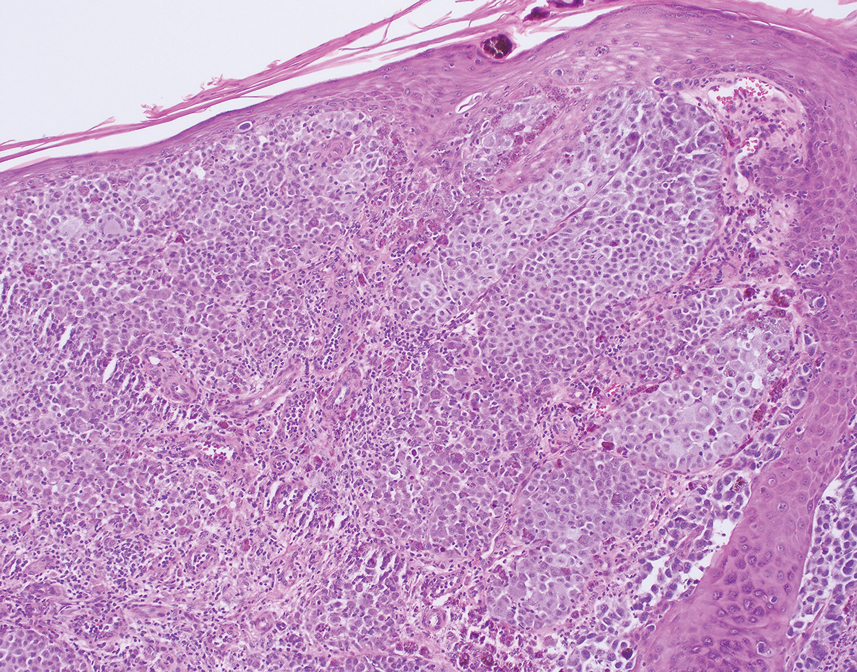

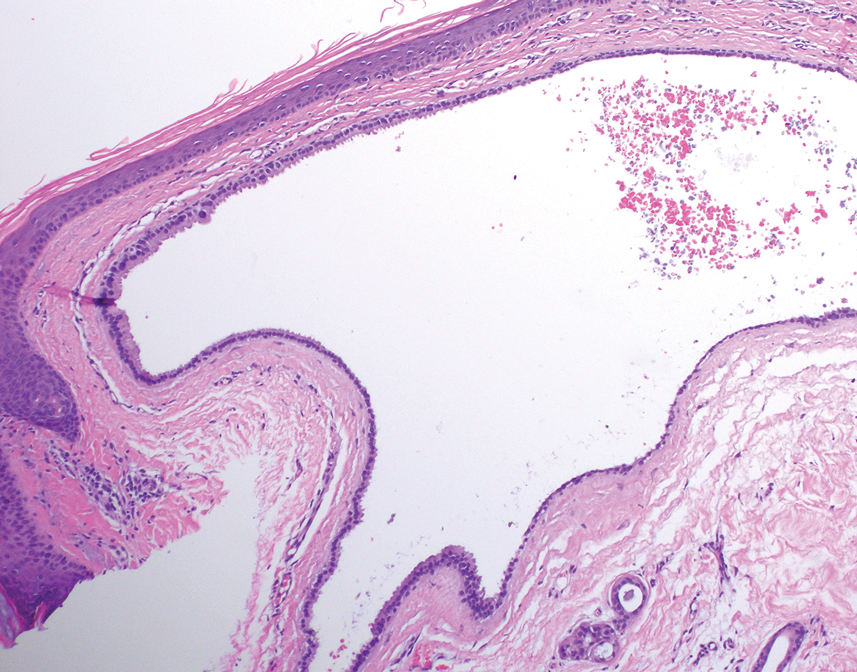

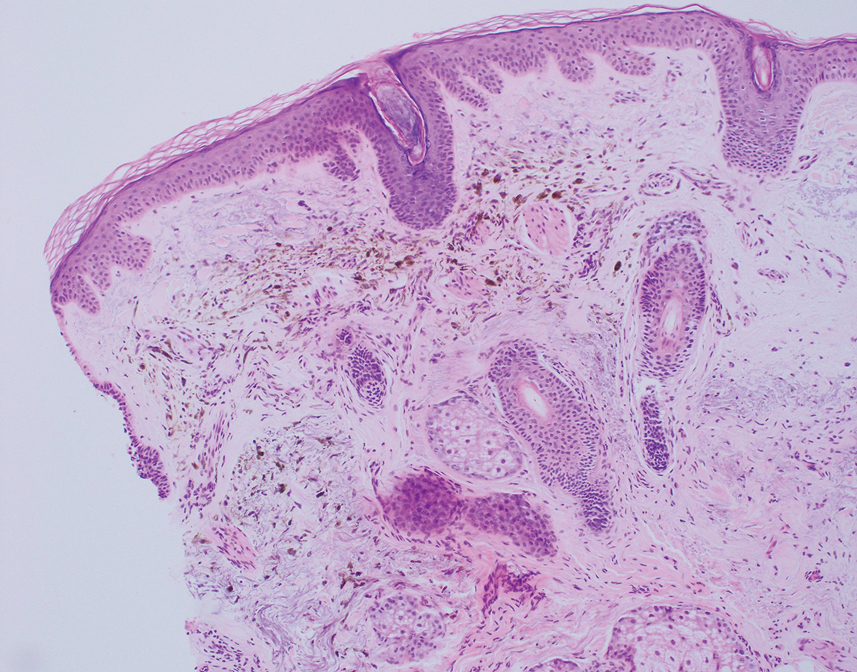

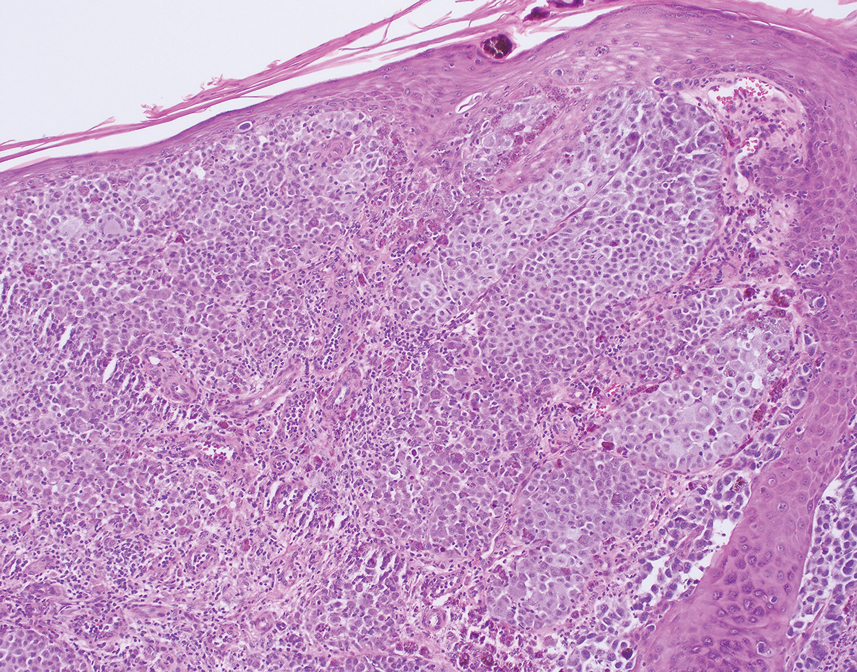

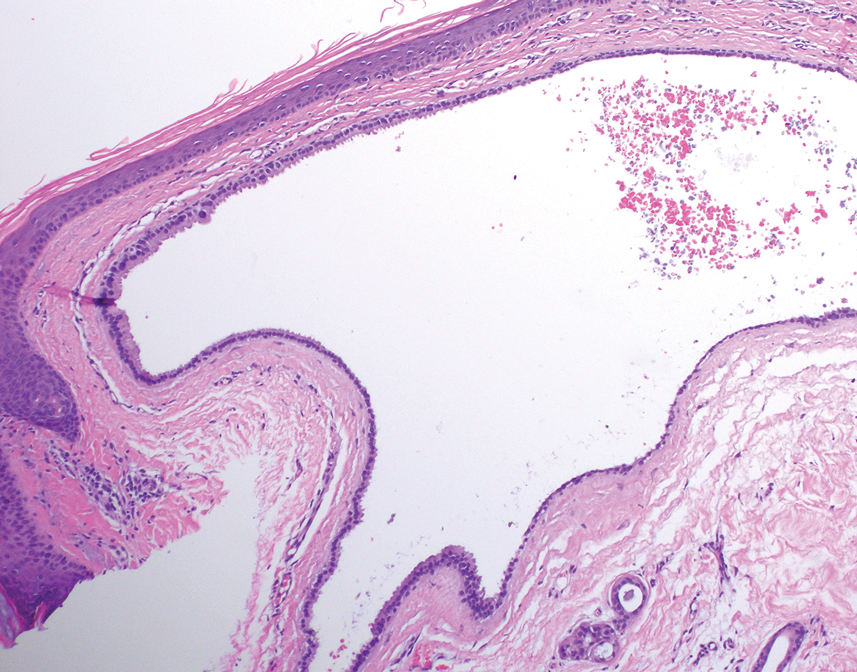

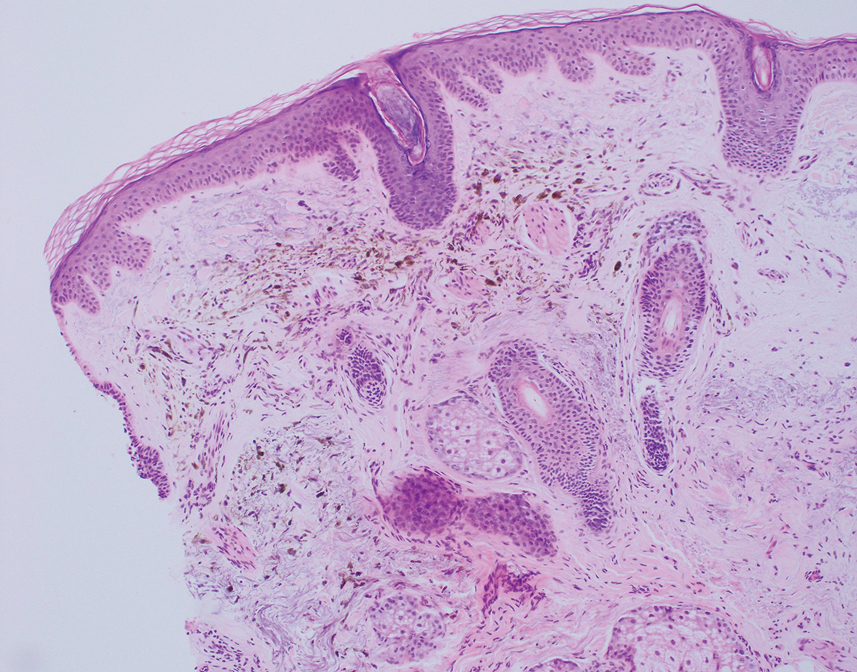

THE DIAGNOSIS: Apocrine Hidrocystoma

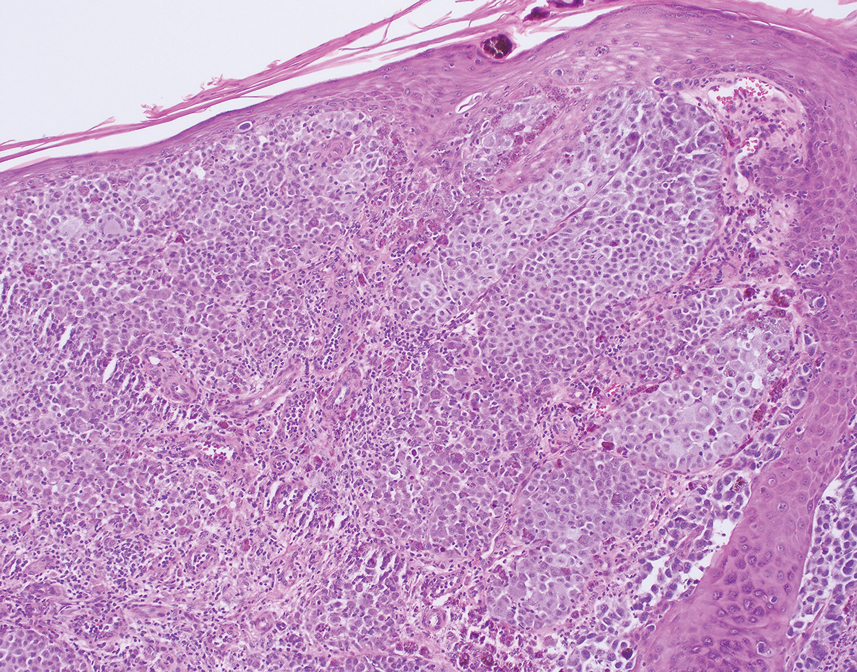

Histology for all 3 lesions demonstrated similar cystic structures lined by a dual layer of epithelial cells, with the outermost layer composed of flattened myoepithelial cells and the inner layer composed of cells with apocrine features (Figure 1). Based on these findings, a diagnosis of apocrine hidrocystoma was made. The patient underwent successful surgical excision shortly thereafter without recurrence at follow-up 1 year later.

Apocrine hidrocystomas are rare benign cystic lesions that are considered to be adenomatous proliferations of apocrine glands. They typically manifest as solitary asymptomatic lesions measuring 3 to 15 mm.1 They tend to appear on the face, usually in the periorbital region, but also have been described on the neck, scalp, trunk, arms, and legs.2-4 Multiple apocrine hidrocystomas can be a marker of 2 rare inherited disorders: Gorlin-Goltz syndrome and Schopf-Schulz-Passarge syndrome.5 Apocrine hidrocystomas may be flesh colored or may have a blue, black, or brown appearance due to the Tyndall effect, in which light with shorter wavelengths is scattered by the contents of the lesions.2 Histologically, apocrine hidrocystomas are cysts lined by a dual layer of epithelial cells. The inner layer is composed of cells with apocrine features, and the outer layer is composed of flattened myoepithelial cells. Due to their range of colors and predilection for sun-exposed surfaces, apocrine hidrocystomas may be mistaken for various malignant neoplasms, including melanoma.6,7