User login

The Gut Microbiome and Cardiac Arrhythmias

The Gut Microbiome and Cardiac Arrhythmias

The extensive surface of the gastrointestinal tract presents an interface between the human body and its environment. Residing within the intestinal lumen, ingested food and various microorganisms are an essential aspect of this relationship. The trillions of microorganisms, primarily commensal bacteria hosted by the human gut, constitute the human gut microbiome.

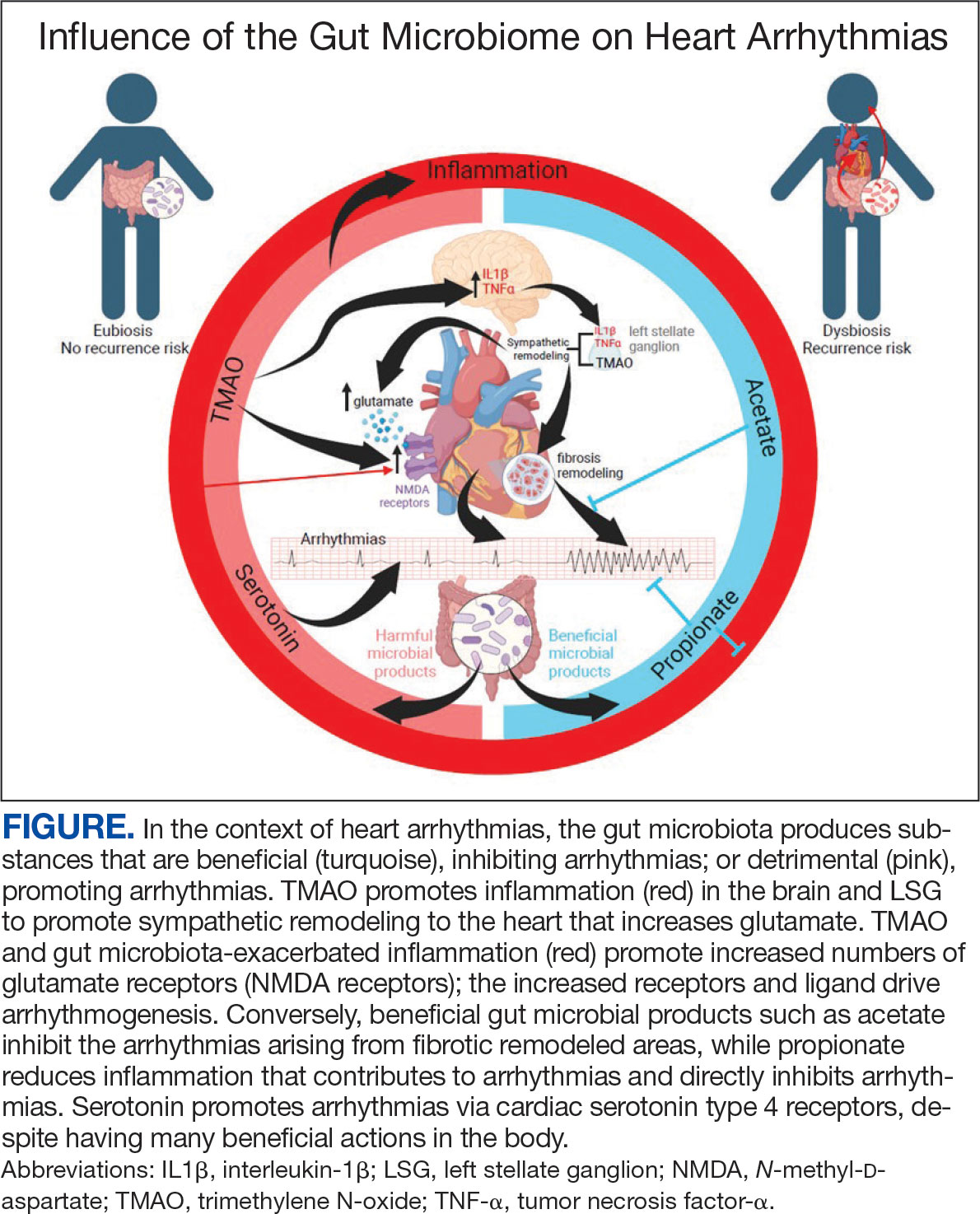

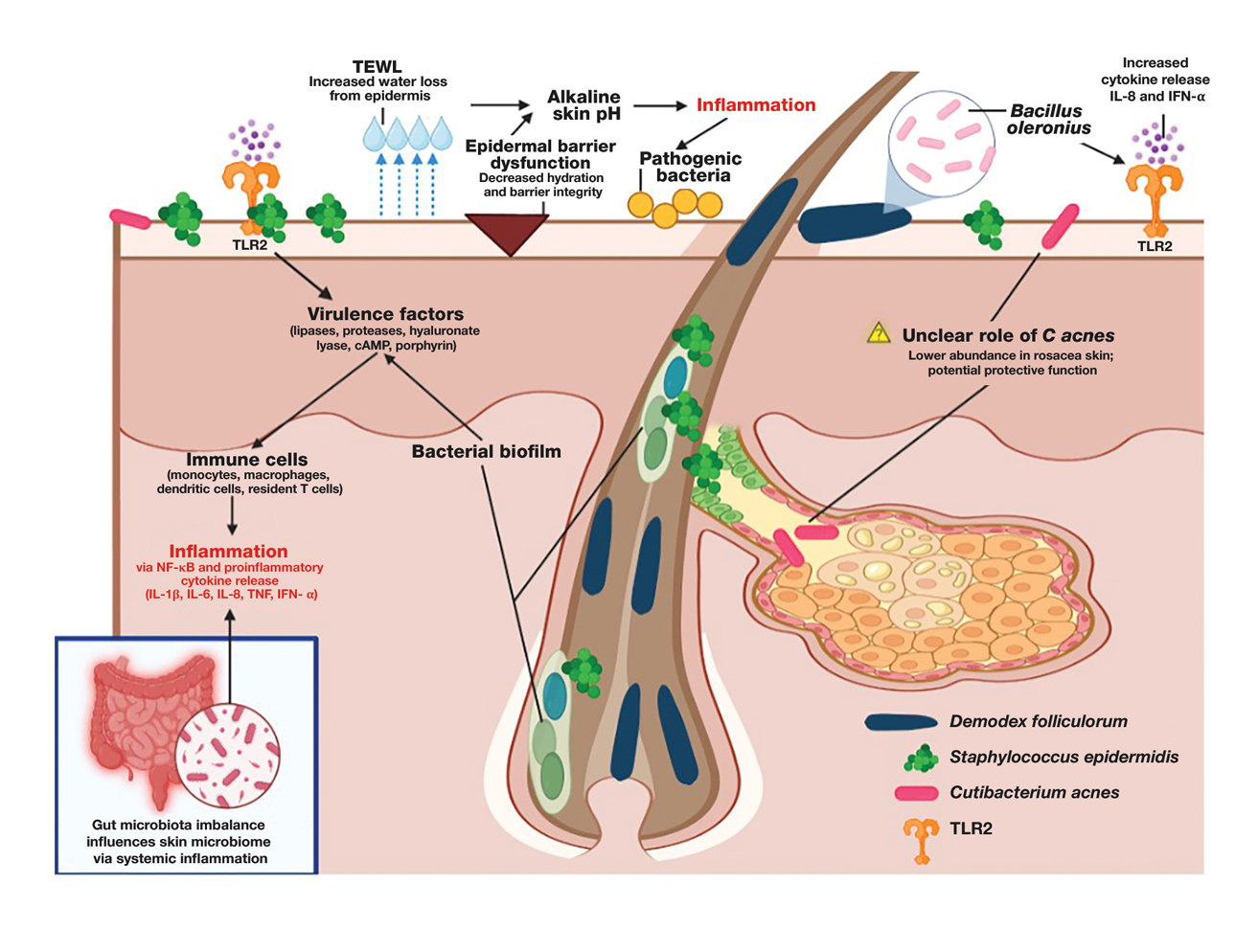

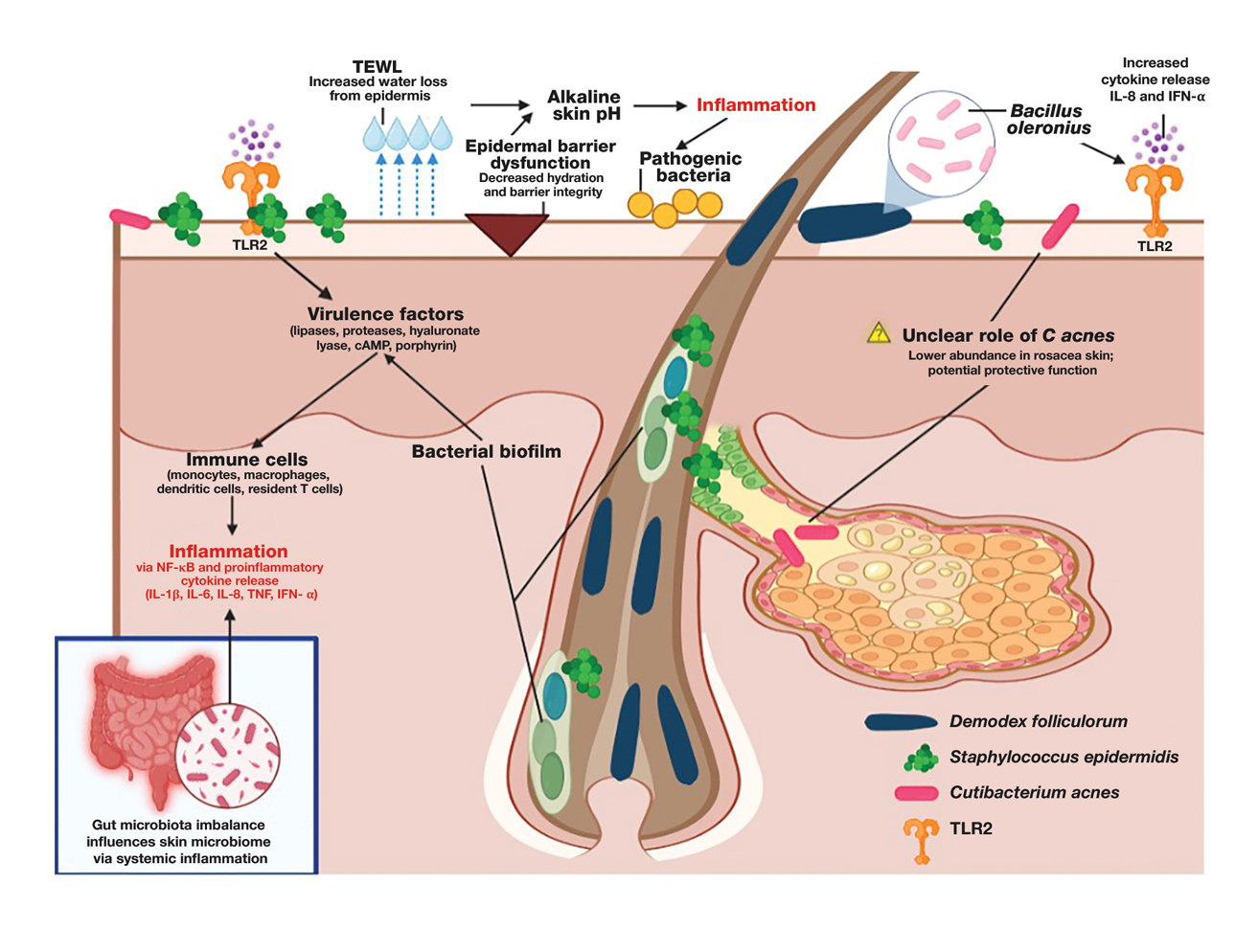

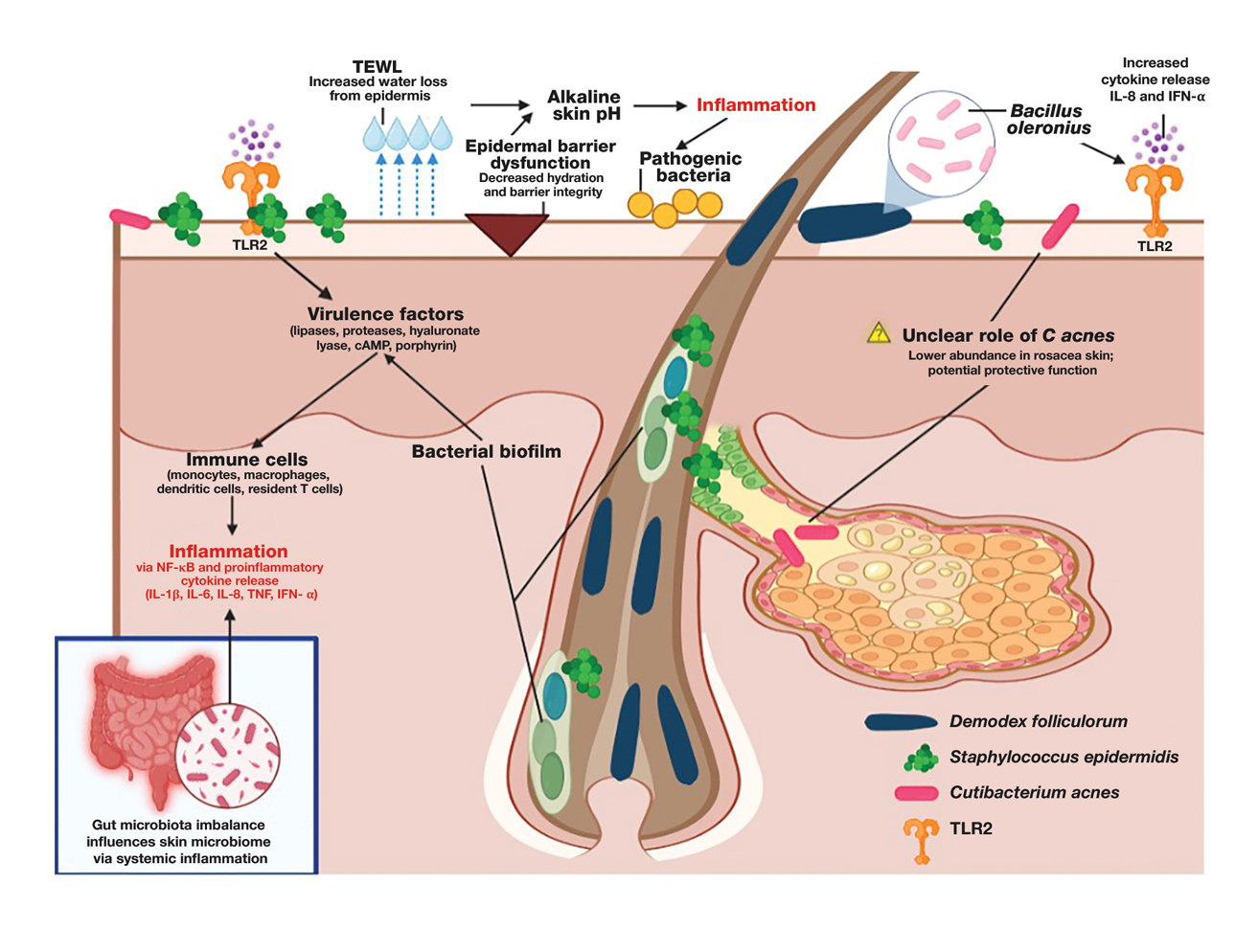

There is growing evidence that the human gut microbiome plays a role in maintaining normal body function and homeostasis.1 Research, such as the National Institute of Health Microbiome Project, is helping to show the impact of gut microorganisms and their negative influence on metabolic diseases and chronic inflammatory disorders.2-5 An imbalance in the microbiota, known as dysbiosis, has been associated with metabolic and cardiovascular diseases (CVD), including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, and coronary artery disease (CAD). Gut dysbiosis has also been associated with cardiac arrhythmias, including atrial fibrillation (AF) and ventricular arrhythmias (Figure).6-12

Whether gut dysbiosis is a cause or effect of the human disease process is unclear. While further research is warranted, some evidence of causation has been found. In 2018, Yoshida et al demonstrated an association between patients with CAD who had a significantly lower burden of the gut bacteria species Bacteroides vulgatus and Bacteroides dorei compared to that of patients without CAD. The study found that administration of these Bacteroides species reduced atherosclerotic lesion formation in atherosclerosis-prone mice.13 If altering gut microbial composition can affect the disease process, it may indicate a causative role for gut dysbiosis in disease pathogenesis. Furthermore, this finding also suggests agents may be used to alter the gut microbiome and potentially prevent and treat diseases. An altered gut microbiome may serve as an early marker for human disease, aiding in timely diagnosis and institution of disease-modifying treatments.

This review outlines the broad relationship of the pathways and intermediaries that may be involved in mediating the interaction between the gut microbiome and cardiac arrhythmias based on rapidly increasing evidence. A comprehensive search among PubMed and Google Scholar databases was conducted to find articles relevant to the topic.

Potential Intermediaries

Potential pathways for how the gut microbiome and cardiovascular system interact are subjects of active research. However, recent research may point to potential mechanisms of the association between the systems. The gut microbiome may influence human physiology through 3 principal routes: the autonomic nervous system, inflammatory pathways, and metabolic processes.

Autonomic Nervous System

The concept of bidirectional communication between the gut and central nervous system, known as the microbiota-gut-brain axis, is widely accepted.14 Proposed mediators of this interaction include the vagus nerve, the sympathetic nervous system, and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis; cytokines produced by the immune system, tryptophan metabolism, and the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs).15,16

The gut microbiome appears to have a direct impact on the autonomic nervous system, through which it can influence cardiovascular function. Muller et al described how the gut microbiome modulated gut-extrinsic sympathetic neurons and that the depletion of gut microbiota led to activation of both brainstem sensory nuclei and efferent sympathetic premotor glutamatergic neurons.16 Meng et al found that systemic injection of the gut microbiota-derived metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) led to significantly increased activity in the paraventricular nucleus, a hypothalamic structure essential to the central autonomic network. Their study demonstrated that systemic TMAO also led to increased left stellate ganglion (LSG) activity, a known contributor to cardiac sympathetic tone.12

Inflammatory Pathways

Inflammatory responses are another pathway for the gut microbiome to influence the cardiovascular system. SCFAs are a set of gut microbial metabolites produced in the colon by bacterial fermentation and decomposition of resistant starches and dietary fibers.17 These metabolites are increasingly recognized for their role in modulating disease processes, including cardiac disease. Aguilar et al found that the progression of atherosclerosis was slowed in apolipoprotein E (Apo-E) knockout mice by a chow diet supplemented with butyrate, a SCFA, suggesting it is an atheroprotective therapeutic agent. Less adhesion and migration of macrophages, reduced inflammation, improved plaque stability, and lowered atherosclerosis progression.18 Wei et al demonstrated in animal models that direct microinjection of the proinflammatory factors interleukin (IL)-1Β and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-αdirectly into the subfornical organ increased heart rate, mean blood pressure, and renal sympathetic nerve activity.19

Metabolic Processes

Serotonin (5-HT), a metabolite of tryptophan, is a neurotransmitter that regulates many bodily functions and plays a significant role in the microbiota-brain gut axis.20 Oral ingestion of the bacterial species Bifidobacterium infantis increased plasma tryptophan in rat models.21 Additionally, many other microorganisms, including species of Candida, Streptococcus, Escherichia, and Enterococcus are known to produce 5-HT.22 While a relationship between the gut microbiome and plasma 5-HT has been established, interactions between 5-HT and the cardiovascular system are complex. Research has shown that stimulation of 5-HT1A receptors produces bradycardic and vasopressor effects, while stimulation of the 5-HT2 receptor induces vasoconstriction and tachycardia.23

A high-fiber diet can lower the incidence of hypertension, although the mechanisms are not clear. One potential reason could be alteration in gut bacteria, as a diet high in fiber has been shown to increase the prevalence of acetate-producing bacteria.24

Atherosclerosis

Research investigating the relationship of the gut microbiome with arrhythmias is in its early stages; however, the connection of the gut microbiome and atherosclerosis is more established.25 Contemporary studies have shown various gut microorganisms associated with atherosclerosis.26 Jie et al reported that patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease had increased Enterobacteriaceae loads and oral cavity-associated bacteria with lower levels of butyrate producing bacteria when compared with healthy controls.27 In addition, microbial metabolites such as TMAO appear to promote atherosclerosis by increasing vascular inflammation and platelet reactivity.26 Researchers are investigating the modulation of these associations to help reduce atherosclerotic burden. Kasahara et al found that Roseburia intestinalis could reduce atherosclerotic disease in mice through the production of butyrate.28 Roberts et al established that administration of TMAO inhibitors reduced TMAO levels while reducing thrombus formation without observable toxicity or increased bleeding risk.29

Atrial Arrhythmias

The gut microbiome can also specifically affect cardiac arrhythmogenesis, and multiple studies suggest possible mediators of this interaction. Certain gut microbiome derived metabolites like TMAO may have a role in promoting AF.30 Other gut microbial metabolites like lipopolysaccharides and indoxyl sulfate are implicated in atrial electrical instability.31,32 Microbe-derived free fatty acids such as palmitic acid and adrenic acid can precipitate arrhythmogenesis. 33,34 Preponderances of certain gut bacteria like Ruminococcus, Streptococcus, and Enterococcus, as well as reductions of Faecalibacterium, Alistipes, Oscillibacter, and Bilophila have been detected in patients with AF.8 Tabata et al found that certain clusters of bacterial groups led by Ruminococcus species seem to show higher prevalence in patients with AF, whereas the genus Enterobacter was significantly lower compared with control subjects. That study also noted that gut microbial composition is affected by diet and antacid use.35 Gut microbiome-derived serotonin may be another mediator for AF, which may be related to the fact that 5-HT4 receptors are present in atrial tissue.36

Ventricular Arrhythmias

A critical component to the development of malignant ventricular arrhythmias is an imbalance in autonomic tone; in particular, the overactivation of the sympathetic nervous system.37 Animal models have shown that augmentation of the sympathetic nervous system plays an essential role in the subsequent development of ventricular arrhythmias. 38 Several studies have established the LSG as an important component of the cardiac sympathetic nervous system pathway. 38,39 Ablation of the LSG has been shown to effectively reduce the burden of malignant arrhythmias, further pointing toward the role of excess sympathetic activity.37,39 Stellate ganglion denervation has become an established method for managing life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias.40

Gut metabolites may have significant effects on cardiac sympathetic activity. Meng et al investigated the effect of TMAO on the LSG in animals and its overall effect on the incidence of ventricular arrhythmias under ischemic conditions. To fully explore this interaction, they examined the effect of TMAO on LSG function though 2 mechanisms: local administration of TMAO within the LSG and systemic administration of TMAO leading to activation of the central sympathetic nervous system. In both protocols, left anterior descending coronary artery occlusion was performed after TMAO administration. Injection of TMAO directly into the LSG was found to significantly increase the cardiac sympathetic tone and incidence of ventricular arrhythmias. In the systemic administration control arm, ventricular arrhythmias were also significantly increased.12

Increased inflammatory states appear to correlate with an increase in sympathetic tone and ventricular arrhythmias.12 In an animal study, direct injection of the proinflammatory factor IL-1Β into the LSG not only resulted in increased inflammation, but aggravated cardiac sympathetic remodeling. This led to a decreased effective refractory period and action potential duration, leading to an increased maximal slope of the restitution curve and higher occurrence of ventricular arrhythmias.41 Shi et al demonstrated that paraventricular nucleus microinjection with TNF-α and IL-1Β also enhanced the cardiac sympathetic afferent reflex, showing that these proinflammatory cytokines not only upregulate the inflammatory response, but can also have excitatory effects that stimulate sympathetic activity and have the potential to be proarrhythmic.19,42 Local and systemic administration of the gut microbe-derived TMAO increased the expression of IL-1Β and TNF-α, thus implicating the microbiome as a potential mediator of the inflammatory response and as another potential pathway for increased ventricular arrhythmias.12

The N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) is found in multiple organs—including the heart—but more specifically in the conducting system and myocardium.43,44 Research has discovered an upregulation of NMDARs in the setting of cardiac sympathetic hyperinnervation in rat models both with healed myocardial necrotic injury and without. The infusion of their ligand, NMDA, provoked ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation in rat models with sympathetic hyperinnervation and healed myocardial necrotic injury.45 Another study found that NMDAR activation provoked ventricular arrhythmias, but also prolonged repolarization and induced electrical instability.46 Proinflammatory markers have been shown to upregulate the expression of NMDARs; more importantly, NMDAR expression has been shown to be significantly increased in the setting of TMAO administration.12,47,48

5-HT also appears to have a substantial association with ventricular arrhythmias in addition to atrial arrhythmias. el-Mahdy demonstrated in anesthetized rats with acute coronary ligation that systemic doses of 5-HT represented a significant dose-dependent increase in the duration of ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation, while also increasing the number of ventricular ectopic beats.49 Certain gut microorganisms are known to produce 5-HT, including those in the genera Streptococcus, Escherichia, and Enterococcus.22 Additionally, oral ingestion of the Bifidobacterium infantis increased plasma levels of tryptophan in rat models.21 The gut microbiome may have significant effects on plasma serotonin levels, and thus have the potential to alter the risk for ventricular arrhythmias.

The deleterious effects of the gut microbiome have been documented. However, it appears to have potential protective effects, and several studies point to the possible mechanisms of this beneficial interaction. Propionate is a SCFA microorganism produced by gut microbial fermentation.50 In a rat model study, Zhou et al found that infusion of sodium propionate significantly reduced ventricular arrhythmias during acute myocardial ischemia or burst stimulation, thus confirming cardioprotective effects.50,51

Proposed mechanisms for reduced susceptibility to ventricular arrhythmias with propionate infusion include parasympathetic activation via the gut-brain axis, anti-inflammatory pathways, and improved cardiac electrophysiology instability.50 In addition butyrate has been found to reduce inflammation and myocardial hypertrophy. Jiang et al demonstrated in rats postmyocardial infarction that butyrate promoted expression of anti-inflammatory M2 macrophage markers, decreased expressions of nerve growth factor and norepinephrine, and decreased the density of nerve fibers for growth-associated protein-43 and tyrosine hydroxylase. The cumulative impact of butyrate led to suppression of inflammation and the inhibition of sympathetic neural remodeling, ultimately resulting in improved cardiac function and reduction in ventricular arrhythmias after myocardial infarction.52

Gut bacteria-derived acetate-mediated reduction in cardiac fibrosis may be another mechanism for the effects on ventricular arrhythmias. Cardiac fibrosis and scar are established as the primary substrate for reentrant ventricular arrhythmias seen in various cardiomyopathies.

Future Directions

The microbiome residing in the human gut has a significant impact on cardiac arrhythmias, the details of which remain unknown. A likely bidirectional relationship exists in which the gut microbiome may affect arrhythmogenesis and in turn be affected by cardiac arrhythmias. The mechanisms of action are not well understood, but likely involve the autonomic nervous system, inflammation, and metabolic pathways.

The gut microbiome is a complex collection of heterogenous microorganisms that have dramatic effects on the human body. Additional research is necessary to identify further associations and causations of gut microorganisms with various human body processes, as well as cardiovascular disease. The microbiome has been shown to directly and indirectly influence the development of different disease states, including the cardiovascular system and cardiac arrhythmias. Several pathways have been proposed through which the gut microbiome can potentially affect cardiac arrhythmogenesis. There are likely several mechanisms simultaneously in operation. Understanding the role of human gut microbiome in the genesis of cardiac arrhythmias not only may improve our understanding of arrhythmias, but also may result in novel treatment options. This could potentially lead to the development of therapeutic options and strategies to modulate the gut microbiome to help detect, prevent, and treat cardiac arrhythmias.

- Sharon G, Sampson TR, Geschwind DH, Mazmanian SK. The central nervous system and the gut microbiome. Cell. 2016;167(4):915-932. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.027

- Karlsson F, Tremaroli V, Nielsen J, Bäckhed F. Assessing the human gut microbiota in metabolic diseases. Diabetes. 2013;62(10):3341-3349. doi:10.2337/db13-0844

- Danneskiold-Samsøe NB, Dias de Freitas Queiroz Barros H, Santos R, et al. Interplay between food and gut microbiota in health and disease. Food Res Int. 2019;115:23-31. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2018.07.043

- Furusawa Y, Obata Y, Fukuda S, et al. Commensal microbe- derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature. 2013;504(7480):446-450. doi:10.1038/nature12721

- Integrative HMP (iHMP) Research Network Consortium. The integrative human microbiome project. Nature. 2019;569(7758):641-648. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1238-8

- Zubcevic J, Richards EM, Yang T, et al. Impaired autonomic nervous system-microbiome circuit in hypertension. Circ Res. 2019;125(1):104-116. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.313965

- Emoto T, Yamashita T, Sasaki N, et al. Analysis of gut microbiota in coronary artery disease patients: a possible link between gut microbiota and coronary artery disease. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2016;23(8):908-921. doi:10.5551/jat.32672

- Zuo K, Li J, Li K, et al. Disordered gut microbiota and alterations in metabolic patterns are associated with atrial fibrillation. Gigascience. 2019;8(6):giz058. doi:10.1093/gigascience/giz058

- Li J, Zhao F, Wang Y, et al. Gut microbiota dysbiosis contributes to the development of hypertension. Microbiome. 2017;5(1):14. doi:10.1186/s40168-016-0222-x

- Qin J, Li Y, Cai Z, et al. A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2012;490(7418):55-60. doi:10.1038/nature11450

- Chang CJ, Lin CS, Lu CC, et al. Ganoderma lucidum reduces obesity in mice by modulating the composition of the gut microbiota. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7489. doi:10.1038/ncomms8489

- Meng G, Zhou X, Wang M, et al. Gut microbederived metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide activates the cardiac autonomic nervous system and facilitates ischemia-induced ventricular arrhythmia via two different pathways. EBioMedicine. 2019;44:656-664. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.03.066

- Yoshida N, Emoto T, Yamashita T, et al. Bacteroides vulgatus and Bacteroides dorei reduce gut microbial lipopolysaccharide production and inhibit atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2018;138(22):2486-2498. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.033714

- Cussotto S, Sandhu KV, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. The neuroendocrinology of the microbiota-gut-brain axis: a behavioural perspective. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2018;51:80-101. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2018.04.002

- Dinan TG, Stilling RM, Stanton C, Cryan JF. Collective unconscious: how gut microbes shape human behavior. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;63:1-9. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.02.021

- Muller PA, Schneeberger M, Matheis F, et al. Microbiota modulate sympathetic neurons via a gutbrain circuit. Nature. 2020;583(7816):441-446. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2474-7

- Ohira H, Tsutsui W, Fujioka Y. Are short chain fatty acids in gut microbiota defensive players for inflammation and atherosclerosis? J Atheroscler Thromb. 2017;24(7):660-672. doi:10.5551/jat.RV17006

- Aguilar EC, Leonel AJ, Teixeira LG, et al. Butyrate impairs atherogenesis by reducing plaque inflammation and vulnerability and decreasing NFêB activation. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;24(6):606-613. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2014.01.002

- Wei SG, Yu Y, Zhang ZH, Felder RB. Proinflammatory cytokines upregulate sympathoexcit - atory mechanisms in the subfornical organ of the rat. Hypertension. 2015;65(5):1126-1133. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.05112

- Dinan TG, Stanton C, Cryan JF. Psychobiotics: a novel class of psychotropic. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74(10):720- 726. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.05.001

- Desbonnet L, Garrett L, Clarke G, Bienenstock J, Dinan TG. The probiotic Bifidobacteria infantis: an assessment of potential antidepressant properties in the rat. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;43(2):164-174. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.03.009

- Lyte M. Probiotics function mechanistically as delivery vehicles for neuroactive compounds: microbial endocrinology in the design and use of probiotics. Bioessays. 2011;33(8):574-581. doi:10.1002/bies.201100024

- Yusuf S, Al-Saady N, Camm AJ. 5-hydroxytryptamine and atrial fibrillation: how significant is this piece in the puzzle? J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2003;14(2):209-214. doi:10.1046/j.1540-8167.2003.02381.x

- Marques FZ, Nelson E, Chu PY, et al. High-fiber diet and acetate supplementation change the gut microbiota and prevent the development of hypertension and heart failure in hypertensive mice. Circulation. 2017;135(10):964-977. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024545

- Björkegren JLM, Lusis AJ. Atherosclerosis: recent developments. Cell. 2022;185(10):1630-1645. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2022.04.004

- Tang WHW, Bäckhed F, Landmesser U, Hazen SL. Intestinal microbiota in cardiovascular health and disease: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(16):2089-2105. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.024

- Jie Z, Xia H, Zhong SL, et al. The gut microbiome in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):845. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00900-1

- Kasahara K, Krautkramer KA, Org E, et al. Interactions between Roseburia intestinalis and diet modulate atherogenesis in a murine model. Nat Microbiol. 2018;3(12):1461- 1471. doi:10.1038/s41564-018-0272-x

- Roberts AB, Gu X, Buffa JA, et al. Development of a gut microbe-targeted nonlethal therapeutic to inhibit thrombosis potential. Nat Med. 2018;24(9):1407-1417. doi:10.1038/s41591-018-0128-1

- Yu L, Meng G, Huang B, et al. A potential relationship between gut microbes and atrial fibrillation: trimethylamine N-oxide, a gut microbe-derived metabolite, facilitates the progression of atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol. 2018;255:92- 98. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.11.071

- Okazaki R, Iwasaki YK, Miyauchi Y, et al. Lipopolysaccharide induces atrial arrhythmogenesis via down-regulation of L-type Ca2+ channel genes in rats. Int Heart J. 2009;50(3):353-363. doi:10.1536/ihj.50.353

- Chen WT, Chen YC, Hsieh MH, et al. The uremic toxin indoxyl sulfate increases pulmonary vein and atrial arrhythmogenesis. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2015;26(2):203- 210. doi:10.1111/jce.12554

- Fretts AM, Mozaffarian D, Siscovick DS, et al. Plasma phospholipid saturated fatty acids and incident atrial fibrillation: the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(3):e000889. doi:10.1161/JAHA.114.000889

- Horas HNS, Nishiumi S, Kawano Y, Kobayashi T, Yoshida M, Azuma T. Adrenic acid as an inflammation enhancer in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2017;623-624:64-75. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2017.04.009

- Tabata T, Yamashita T, Hosomi K, et al. Gut microbial composition in patients with atrial fibrillation: effects of diet and drugs. Heart Vessels. 2021;36(1):105-114. doi:10.1007/s00380-020-01669-y

- López-Rodriguez ML, Benhamú B, Morcillo MJ, et al. 5-HT(4) receptor antagonists: structure-affinity relationships and ligand-receptor interactions. Curr Top Med Chem. 2002;2(6):625-641. doi:10.2174/1568026023393769

- Yu L, Zhou L, Cao G, et al. Optogenetic modulation of cardiac sympathetic nerve activity to prevent ventricular arrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(22):2778-2790. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.09.1107

- Schwartz PJ, Vanoli E. Cardiac arrhythmias elicited by interaction between acute myocardial ischemia and sympathetic hyperactivity: a new experimental model for the study of antiarrhythmic drugs. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1981;3(6):1251-1259. doi:10.1097/00005344-198111000-00012

- Puddu PE, Jouve R, Langlet F, Guillen JC, Lanti M, Reale A. Prevention of postischemic ventricular fibrillation late after right or left stellate ganglionectomy in dogs. Circulation. 1988;77(4):935-946. doi:10.1161/01.cir.77.4.935

- Vaseghi M, Gima J, Kanaan C, et al. Cardiac sympathetic denervation in patients with refractory ventricular arrhythmias or electrical storm: intermediate and longterm follow-up. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11(3):360-366. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.11.028

- Wang M, Li S, Zhou X, et al. Increased inflammation promotes ventricular arrhythmia through aggravating left stellate ganglion remodeling in a canine ischemia model. Int J Cardiol. 2017;248:286-293. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.08.011

- Shi Z, Gan XB, Fan ZD, et al. Inflammatory cytokines in paraventricular nucleus modulate sympathetic activity and cardiac sympathetic afferent reflex in rats. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2011;203(2):289-297. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1716.2011.02313.x

- Gill S, Veinot J, Kavanagh M, Pulido O. Human heart glutamate receptors - implications for toxicology, food safety, and drug discovery. Toxicol Pathol. 2007;35(3):411-417. doi:10.1080/01926230701230361

- Govoruskina N, Jakovljevic V, Zivkovic V, et al. The role of cardiac N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in heart conditioning— effects on heart function and oxidative stress. Biomolecules. 2020;10(7):1065. doi:10.3390/biom10071065

- Lü J, Gao X, Gu J, et al. Nerve sprouting contributes to increased severity of ventricular tachyarrhythmias by upregulating iGluRs in rats with healed myocardial necrotic injury. J Mol Neurosci. 2012;48(2):448-455. doi:10.1007/s12031-012-9720-x

- Shi S, Liu T, Li Y, et al. Chronic N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor activation induces cardiac electrical remodeling and increases susceptibility to ventricular arrhythmias. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2014;37(10):1367-1377. doi:10.1111/pace.12430

- Zhang Z, Bassam B, Thomas AG, et al. Maternal inflammation leads to impaired glutamate homeostasis and upregulation of glutamate carboxypeptidase II in activated microglia in the fetal/newborn rabbit brain. Neurobiol Dis. 2016;94:116-128. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2016.06.010

- Wu LJ, Toyoda H, Zhao MG, et al. Upregulation of forebrain NMDA NR2B receptors contributes to behavioral sensitization after inflammation. J Neurosci. 2005;25(48):11107-11116. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1678-05.2005

- el-Mahdy SA. 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) enhances ventricular arrhythmias induced by acute coronary artery ligation in rats. Res Commun Chem Pathol Pharmacol. 1990;68(3):383-386.

- Zhou M, Li D, Xie K, et al. The short-chain fatty acid propionate improved ventricular electrical remodeling in a rat model with myocardial infarction. Food Funct. 2021;12(24):12580-12593. doi:10.1039/d1fo02040d

- Bartolomaeus H, Balogh A, Yakoub M, et al. Short-chain fatty acid propionate protects from hypertensive cardiovascular damage. Circulation. 2019;139(11):1407-1421. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.036652

- Jiang X, Huang X, Tong Y, Gao H. Butyrate improves cardiac function and sympathetic neural remodeling following myocardial infarction in rats. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2020;98(6):391-399. doi:10.1139/cjpp-2019-0531

The extensive surface of the gastrointestinal tract presents an interface between the human body and its environment. Residing within the intestinal lumen, ingested food and various microorganisms are an essential aspect of this relationship. The trillions of microorganisms, primarily commensal bacteria hosted by the human gut, constitute the human gut microbiome.

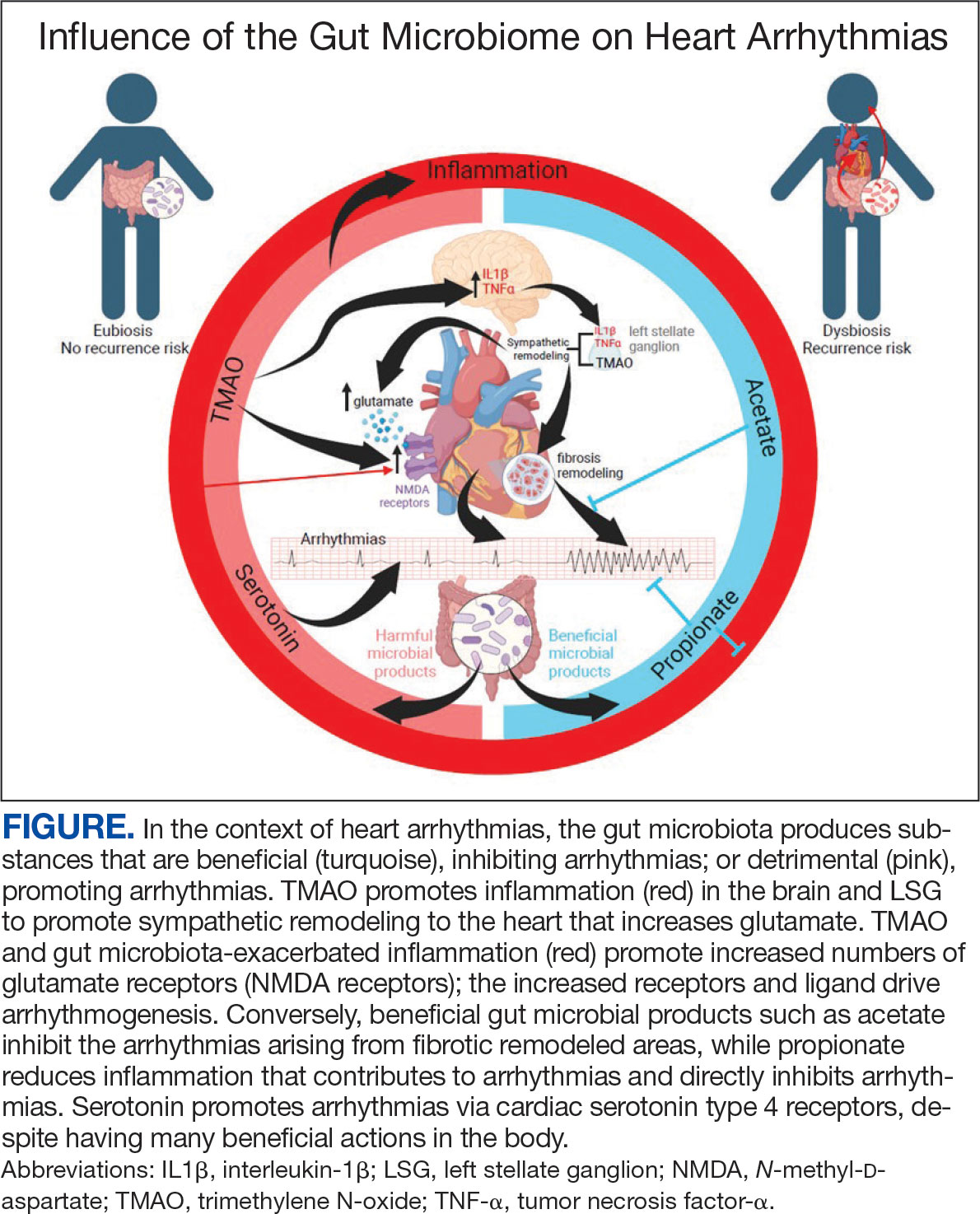

There is growing evidence that the human gut microbiome plays a role in maintaining normal body function and homeostasis.1 Research, such as the National Institute of Health Microbiome Project, is helping to show the impact of gut microorganisms and their negative influence on metabolic diseases and chronic inflammatory disorders.2-5 An imbalance in the microbiota, known as dysbiosis, has been associated with metabolic and cardiovascular diseases (CVD), including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, and coronary artery disease (CAD). Gut dysbiosis has also been associated with cardiac arrhythmias, including atrial fibrillation (AF) and ventricular arrhythmias (Figure).6-12

Whether gut dysbiosis is a cause or effect of the human disease process is unclear. While further research is warranted, some evidence of causation has been found. In 2018, Yoshida et al demonstrated an association between patients with CAD who had a significantly lower burden of the gut bacteria species Bacteroides vulgatus and Bacteroides dorei compared to that of patients without CAD. The study found that administration of these Bacteroides species reduced atherosclerotic lesion formation in atherosclerosis-prone mice.13 If altering gut microbial composition can affect the disease process, it may indicate a causative role for gut dysbiosis in disease pathogenesis. Furthermore, this finding also suggests agents may be used to alter the gut microbiome and potentially prevent and treat diseases. An altered gut microbiome may serve as an early marker for human disease, aiding in timely diagnosis and institution of disease-modifying treatments.

This review outlines the broad relationship of the pathways and intermediaries that may be involved in mediating the interaction between the gut microbiome and cardiac arrhythmias based on rapidly increasing evidence. A comprehensive search among PubMed and Google Scholar databases was conducted to find articles relevant to the topic.

Potential Intermediaries

Potential pathways for how the gut microbiome and cardiovascular system interact are subjects of active research. However, recent research may point to potential mechanisms of the association between the systems. The gut microbiome may influence human physiology through 3 principal routes: the autonomic nervous system, inflammatory pathways, and metabolic processes.

Autonomic Nervous System

The concept of bidirectional communication between the gut and central nervous system, known as the microbiota-gut-brain axis, is widely accepted.14 Proposed mediators of this interaction include the vagus nerve, the sympathetic nervous system, and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis; cytokines produced by the immune system, tryptophan metabolism, and the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs).15,16

The gut microbiome appears to have a direct impact on the autonomic nervous system, through which it can influence cardiovascular function. Muller et al described how the gut microbiome modulated gut-extrinsic sympathetic neurons and that the depletion of gut microbiota led to activation of both brainstem sensory nuclei and efferent sympathetic premotor glutamatergic neurons.16 Meng et al found that systemic injection of the gut microbiota-derived metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) led to significantly increased activity in the paraventricular nucleus, a hypothalamic structure essential to the central autonomic network. Their study demonstrated that systemic TMAO also led to increased left stellate ganglion (LSG) activity, a known contributor to cardiac sympathetic tone.12

Inflammatory Pathways

Inflammatory responses are another pathway for the gut microbiome to influence the cardiovascular system. SCFAs are a set of gut microbial metabolites produced in the colon by bacterial fermentation and decomposition of resistant starches and dietary fibers.17 These metabolites are increasingly recognized for their role in modulating disease processes, including cardiac disease. Aguilar et al found that the progression of atherosclerosis was slowed in apolipoprotein E (Apo-E) knockout mice by a chow diet supplemented with butyrate, a SCFA, suggesting it is an atheroprotective therapeutic agent. Less adhesion and migration of macrophages, reduced inflammation, improved plaque stability, and lowered atherosclerosis progression.18 Wei et al demonstrated in animal models that direct microinjection of the proinflammatory factors interleukin (IL)-1Β and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-αdirectly into the subfornical organ increased heart rate, mean blood pressure, and renal sympathetic nerve activity.19

Metabolic Processes

Serotonin (5-HT), a metabolite of tryptophan, is a neurotransmitter that regulates many bodily functions and plays a significant role in the microbiota-brain gut axis.20 Oral ingestion of the bacterial species Bifidobacterium infantis increased plasma tryptophan in rat models.21 Additionally, many other microorganisms, including species of Candida, Streptococcus, Escherichia, and Enterococcus are known to produce 5-HT.22 While a relationship between the gut microbiome and plasma 5-HT has been established, interactions between 5-HT and the cardiovascular system are complex. Research has shown that stimulation of 5-HT1A receptors produces bradycardic and vasopressor effects, while stimulation of the 5-HT2 receptor induces vasoconstriction and tachycardia.23

A high-fiber diet can lower the incidence of hypertension, although the mechanisms are not clear. One potential reason could be alteration in gut bacteria, as a diet high in fiber has been shown to increase the prevalence of acetate-producing bacteria.24

Atherosclerosis

Research investigating the relationship of the gut microbiome with arrhythmias is in its early stages; however, the connection of the gut microbiome and atherosclerosis is more established.25 Contemporary studies have shown various gut microorganisms associated with atherosclerosis.26 Jie et al reported that patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease had increased Enterobacteriaceae loads and oral cavity-associated bacteria with lower levels of butyrate producing bacteria when compared with healthy controls.27 In addition, microbial metabolites such as TMAO appear to promote atherosclerosis by increasing vascular inflammation and platelet reactivity.26 Researchers are investigating the modulation of these associations to help reduce atherosclerotic burden. Kasahara et al found that Roseburia intestinalis could reduce atherosclerotic disease in mice through the production of butyrate.28 Roberts et al established that administration of TMAO inhibitors reduced TMAO levels while reducing thrombus formation without observable toxicity or increased bleeding risk.29

Atrial Arrhythmias

The gut microbiome can also specifically affect cardiac arrhythmogenesis, and multiple studies suggest possible mediators of this interaction. Certain gut microbiome derived metabolites like TMAO may have a role in promoting AF.30 Other gut microbial metabolites like lipopolysaccharides and indoxyl sulfate are implicated in atrial electrical instability.31,32 Microbe-derived free fatty acids such as palmitic acid and adrenic acid can precipitate arrhythmogenesis. 33,34 Preponderances of certain gut bacteria like Ruminococcus, Streptococcus, and Enterococcus, as well as reductions of Faecalibacterium, Alistipes, Oscillibacter, and Bilophila have been detected in patients with AF.8 Tabata et al found that certain clusters of bacterial groups led by Ruminococcus species seem to show higher prevalence in patients with AF, whereas the genus Enterobacter was significantly lower compared with control subjects. That study also noted that gut microbial composition is affected by diet and antacid use.35 Gut microbiome-derived serotonin may be another mediator for AF, which may be related to the fact that 5-HT4 receptors are present in atrial tissue.36

Ventricular Arrhythmias

A critical component to the development of malignant ventricular arrhythmias is an imbalance in autonomic tone; in particular, the overactivation of the sympathetic nervous system.37 Animal models have shown that augmentation of the sympathetic nervous system plays an essential role in the subsequent development of ventricular arrhythmias. 38 Several studies have established the LSG as an important component of the cardiac sympathetic nervous system pathway. 38,39 Ablation of the LSG has been shown to effectively reduce the burden of malignant arrhythmias, further pointing toward the role of excess sympathetic activity.37,39 Stellate ganglion denervation has become an established method for managing life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias.40

Gut metabolites may have significant effects on cardiac sympathetic activity. Meng et al investigated the effect of TMAO on the LSG in animals and its overall effect on the incidence of ventricular arrhythmias under ischemic conditions. To fully explore this interaction, they examined the effect of TMAO on LSG function though 2 mechanisms: local administration of TMAO within the LSG and systemic administration of TMAO leading to activation of the central sympathetic nervous system. In both protocols, left anterior descending coronary artery occlusion was performed after TMAO administration. Injection of TMAO directly into the LSG was found to significantly increase the cardiac sympathetic tone and incidence of ventricular arrhythmias. In the systemic administration control arm, ventricular arrhythmias were also significantly increased.12

Increased inflammatory states appear to correlate with an increase in sympathetic tone and ventricular arrhythmias.12 In an animal study, direct injection of the proinflammatory factor IL-1Β into the LSG not only resulted in increased inflammation, but aggravated cardiac sympathetic remodeling. This led to a decreased effective refractory period and action potential duration, leading to an increased maximal slope of the restitution curve and higher occurrence of ventricular arrhythmias.41 Shi et al demonstrated that paraventricular nucleus microinjection with TNF-α and IL-1Β also enhanced the cardiac sympathetic afferent reflex, showing that these proinflammatory cytokines not only upregulate the inflammatory response, but can also have excitatory effects that stimulate sympathetic activity and have the potential to be proarrhythmic.19,42 Local and systemic administration of the gut microbe-derived TMAO increased the expression of IL-1Β and TNF-α, thus implicating the microbiome as a potential mediator of the inflammatory response and as another potential pathway for increased ventricular arrhythmias.12

The N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) is found in multiple organs—including the heart—but more specifically in the conducting system and myocardium.43,44 Research has discovered an upregulation of NMDARs in the setting of cardiac sympathetic hyperinnervation in rat models both with healed myocardial necrotic injury and without. The infusion of their ligand, NMDA, provoked ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation in rat models with sympathetic hyperinnervation and healed myocardial necrotic injury.45 Another study found that NMDAR activation provoked ventricular arrhythmias, but also prolonged repolarization and induced electrical instability.46 Proinflammatory markers have been shown to upregulate the expression of NMDARs; more importantly, NMDAR expression has been shown to be significantly increased in the setting of TMAO administration.12,47,48

5-HT also appears to have a substantial association with ventricular arrhythmias in addition to atrial arrhythmias. el-Mahdy demonstrated in anesthetized rats with acute coronary ligation that systemic doses of 5-HT represented a significant dose-dependent increase in the duration of ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation, while also increasing the number of ventricular ectopic beats.49 Certain gut microorganisms are known to produce 5-HT, including those in the genera Streptococcus, Escherichia, and Enterococcus.22 Additionally, oral ingestion of the Bifidobacterium infantis increased plasma levels of tryptophan in rat models.21 The gut microbiome may have significant effects on plasma serotonin levels, and thus have the potential to alter the risk for ventricular arrhythmias.

The deleterious effects of the gut microbiome have been documented. However, it appears to have potential protective effects, and several studies point to the possible mechanisms of this beneficial interaction. Propionate is a SCFA microorganism produced by gut microbial fermentation.50 In a rat model study, Zhou et al found that infusion of sodium propionate significantly reduced ventricular arrhythmias during acute myocardial ischemia or burst stimulation, thus confirming cardioprotective effects.50,51

Proposed mechanisms for reduced susceptibility to ventricular arrhythmias with propionate infusion include parasympathetic activation via the gut-brain axis, anti-inflammatory pathways, and improved cardiac electrophysiology instability.50 In addition butyrate has been found to reduce inflammation and myocardial hypertrophy. Jiang et al demonstrated in rats postmyocardial infarction that butyrate promoted expression of anti-inflammatory M2 macrophage markers, decreased expressions of nerve growth factor and norepinephrine, and decreased the density of nerve fibers for growth-associated protein-43 and tyrosine hydroxylase. The cumulative impact of butyrate led to suppression of inflammation and the inhibition of sympathetic neural remodeling, ultimately resulting in improved cardiac function and reduction in ventricular arrhythmias after myocardial infarction.52

Gut bacteria-derived acetate-mediated reduction in cardiac fibrosis may be another mechanism for the effects on ventricular arrhythmias. Cardiac fibrosis and scar are established as the primary substrate for reentrant ventricular arrhythmias seen in various cardiomyopathies.

Future Directions

The microbiome residing in the human gut has a significant impact on cardiac arrhythmias, the details of which remain unknown. A likely bidirectional relationship exists in which the gut microbiome may affect arrhythmogenesis and in turn be affected by cardiac arrhythmias. The mechanisms of action are not well understood, but likely involve the autonomic nervous system, inflammation, and metabolic pathways.

The gut microbiome is a complex collection of heterogenous microorganisms that have dramatic effects on the human body. Additional research is necessary to identify further associations and causations of gut microorganisms with various human body processes, as well as cardiovascular disease. The microbiome has been shown to directly and indirectly influence the development of different disease states, including the cardiovascular system and cardiac arrhythmias. Several pathways have been proposed through which the gut microbiome can potentially affect cardiac arrhythmogenesis. There are likely several mechanisms simultaneously in operation. Understanding the role of human gut microbiome in the genesis of cardiac arrhythmias not only may improve our understanding of arrhythmias, but also may result in novel treatment options. This could potentially lead to the development of therapeutic options and strategies to modulate the gut microbiome to help detect, prevent, and treat cardiac arrhythmias.

The extensive surface of the gastrointestinal tract presents an interface between the human body and its environment. Residing within the intestinal lumen, ingested food and various microorganisms are an essential aspect of this relationship. The trillions of microorganisms, primarily commensal bacteria hosted by the human gut, constitute the human gut microbiome.

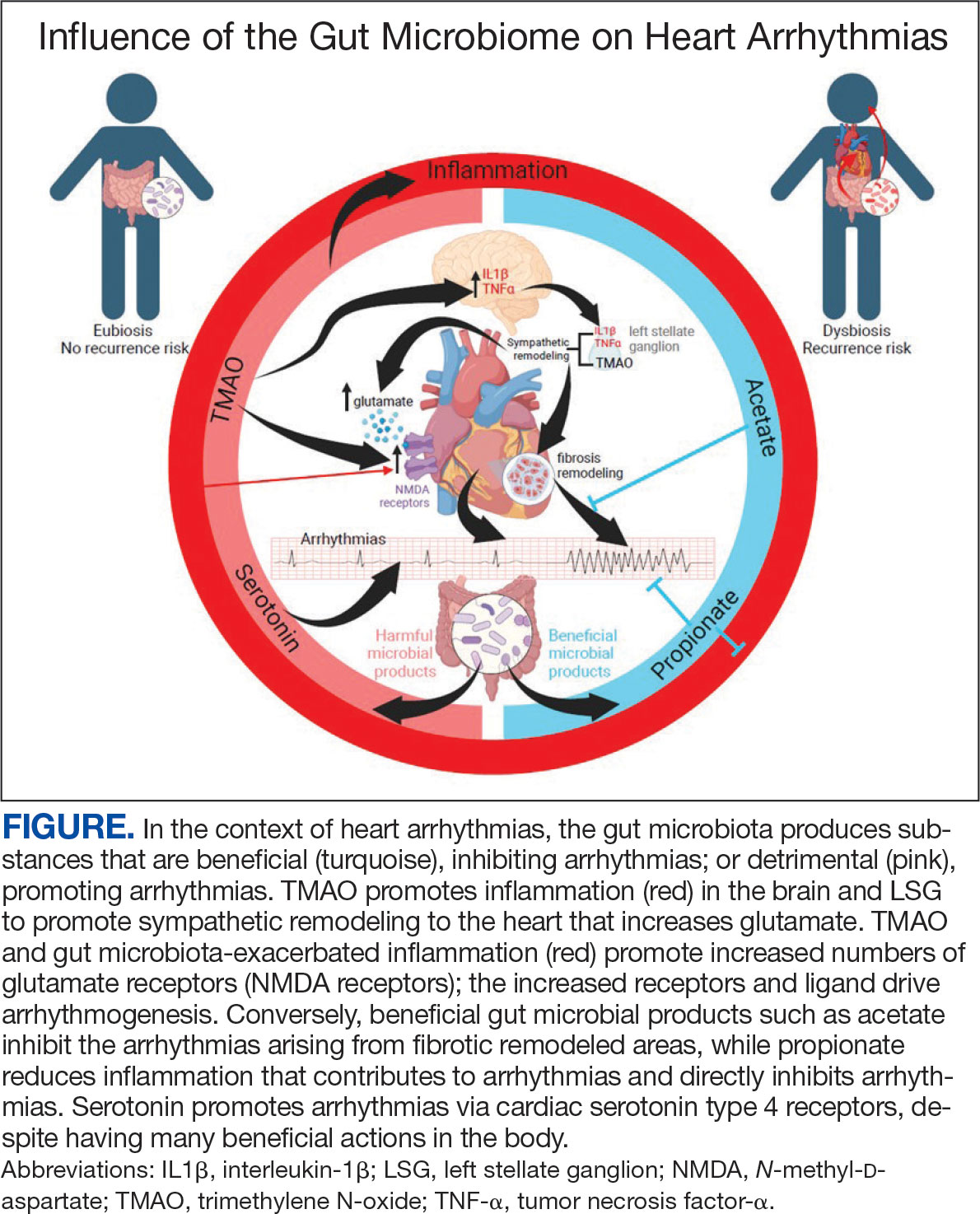

There is growing evidence that the human gut microbiome plays a role in maintaining normal body function and homeostasis.1 Research, such as the National Institute of Health Microbiome Project, is helping to show the impact of gut microorganisms and their negative influence on metabolic diseases and chronic inflammatory disorders.2-5 An imbalance in the microbiota, known as dysbiosis, has been associated with metabolic and cardiovascular diseases (CVD), including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, and coronary artery disease (CAD). Gut dysbiosis has also been associated with cardiac arrhythmias, including atrial fibrillation (AF) and ventricular arrhythmias (Figure).6-12

Whether gut dysbiosis is a cause or effect of the human disease process is unclear. While further research is warranted, some evidence of causation has been found. In 2018, Yoshida et al demonstrated an association between patients with CAD who had a significantly lower burden of the gut bacteria species Bacteroides vulgatus and Bacteroides dorei compared to that of patients without CAD. The study found that administration of these Bacteroides species reduced atherosclerotic lesion formation in atherosclerosis-prone mice.13 If altering gut microbial composition can affect the disease process, it may indicate a causative role for gut dysbiosis in disease pathogenesis. Furthermore, this finding also suggests agents may be used to alter the gut microbiome and potentially prevent and treat diseases. An altered gut microbiome may serve as an early marker for human disease, aiding in timely diagnosis and institution of disease-modifying treatments.

This review outlines the broad relationship of the pathways and intermediaries that may be involved in mediating the interaction between the gut microbiome and cardiac arrhythmias based on rapidly increasing evidence. A comprehensive search among PubMed and Google Scholar databases was conducted to find articles relevant to the topic.

Potential Intermediaries

Potential pathways for how the gut microbiome and cardiovascular system interact are subjects of active research. However, recent research may point to potential mechanisms of the association between the systems. The gut microbiome may influence human physiology through 3 principal routes: the autonomic nervous system, inflammatory pathways, and metabolic processes.

Autonomic Nervous System

The concept of bidirectional communication between the gut and central nervous system, known as the microbiota-gut-brain axis, is widely accepted.14 Proposed mediators of this interaction include the vagus nerve, the sympathetic nervous system, and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis; cytokines produced by the immune system, tryptophan metabolism, and the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs).15,16

The gut microbiome appears to have a direct impact on the autonomic nervous system, through which it can influence cardiovascular function. Muller et al described how the gut microbiome modulated gut-extrinsic sympathetic neurons and that the depletion of gut microbiota led to activation of both brainstem sensory nuclei and efferent sympathetic premotor glutamatergic neurons.16 Meng et al found that systemic injection of the gut microbiota-derived metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) led to significantly increased activity in the paraventricular nucleus, a hypothalamic structure essential to the central autonomic network. Their study demonstrated that systemic TMAO also led to increased left stellate ganglion (LSG) activity, a known contributor to cardiac sympathetic tone.12

Inflammatory Pathways

Inflammatory responses are another pathway for the gut microbiome to influence the cardiovascular system. SCFAs are a set of gut microbial metabolites produced in the colon by bacterial fermentation and decomposition of resistant starches and dietary fibers.17 These metabolites are increasingly recognized for their role in modulating disease processes, including cardiac disease. Aguilar et al found that the progression of atherosclerosis was slowed in apolipoprotein E (Apo-E) knockout mice by a chow diet supplemented with butyrate, a SCFA, suggesting it is an atheroprotective therapeutic agent. Less adhesion and migration of macrophages, reduced inflammation, improved plaque stability, and lowered atherosclerosis progression.18 Wei et al demonstrated in animal models that direct microinjection of the proinflammatory factors interleukin (IL)-1Β and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-αdirectly into the subfornical organ increased heart rate, mean blood pressure, and renal sympathetic nerve activity.19

Metabolic Processes

Serotonin (5-HT), a metabolite of tryptophan, is a neurotransmitter that regulates many bodily functions and plays a significant role in the microbiota-brain gut axis.20 Oral ingestion of the bacterial species Bifidobacterium infantis increased plasma tryptophan in rat models.21 Additionally, many other microorganisms, including species of Candida, Streptococcus, Escherichia, and Enterococcus are known to produce 5-HT.22 While a relationship between the gut microbiome and plasma 5-HT has been established, interactions between 5-HT and the cardiovascular system are complex. Research has shown that stimulation of 5-HT1A receptors produces bradycardic and vasopressor effects, while stimulation of the 5-HT2 receptor induces vasoconstriction and tachycardia.23

A high-fiber diet can lower the incidence of hypertension, although the mechanisms are not clear. One potential reason could be alteration in gut bacteria, as a diet high in fiber has been shown to increase the prevalence of acetate-producing bacteria.24

Atherosclerosis

Research investigating the relationship of the gut microbiome with arrhythmias is in its early stages; however, the connection of the gut microbiome and atherosclerosis is more established.25 Contemporary studies have shown various gut microorganisms associated with atherosclerosis.26 Jie et al reported that patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease had increased Enterobacteriaceae loads and oral cavity-associated bacteria with lower levels of butyrate producing bacteria when compared with healthy controls.27 In addition, microbial metabolites such as TMAO appear to promote atherosclerosis by increasing vascular inflammation and platelet reactivity.26 Researchers are investigating the modulation of these associations to help reduce atherosclerotic burden. Kasahara et al found that Roseburia intestinalis could reduce atherosclerotic disease in mice through the production of butyrate.28 Roberts et al established that administration of TMAO inhibitors reduced TMAO levels while reducing thrombus formation without observable toxicity or increased bleeding risk.29

Atrial Arrhythmias

The gut microbiome can also specifically affect cardiac arrhythmogenesis, and multiple studies suggest possible mediators of this interaction. Certain gut microbiome derived metabolites like TMAO may have a role in promoting AF.30 Other gut microbial metabolites like lipopolysaccharides and indoxyl sulfate are implicated in atrial electrical instability.31,32 Microbe-derived free fatty acids such as palmitic acid and adrenic acid can precipitate arrhythmogenesis. 33,34 Preponderances of certain gut bacteria like Ruminococcus, Streptococcus, and Enterococcus, as well as reductions of Faecalibacterium, Alistipes, Oscillibacter, and Bilophila have been detected in patients with AF.8 Tabata et al found that certain clusters of bacterial groups led by Ruminococcus species seem to show higher prevalence in patients with AF, whereas the genus Enterobacter was significantly lower compared with control subjects. That study also noted that gut microbial composition is affected by diet and antacid use.35 Gut microbiome-derived serotonin may be another mediator for AF, which may be related to the fact that 5-HT4 receptors are present in atrial tissue.36

Ventricular Arrhythmias

A critical component to the development of malignant ventricular arrhythmias is an imbalance in autonomic tone; in particular, the overactivation of the sympathetic nervous system.37 Animal models have shown that augmentation of the sympathetic nervous system plays an essential role in the subsequent development of ventricular arrhythmias. 38 Several studies have established the LSG as an important component of the cardiac sympathetic nervous system pathway. 38,39 Ablation of the LSG has been shown to effectively reduce the burden of malignant arrhythmias, further pointing toward the role of excess sympathetic activity.37,39 Stellate ganglion denervation has become an established method for managing life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias.40

Gut metabolites may have significant effects on cardiac sympathetic activity. Meng et al investigated the effect of TMAO on the LSG in animals and its overall effect on the incidence of ventricular arrhythmias under ischemic conditions. To fully explore this interaction, they examined the effect of TMAO on LSG function though 2 mechanisms: local administration of TMAO within the LSG and systemic administration of TMAO leading to activation of the central sympathetic nervous system. In both protocols, left anterior descending coronary artery occlusion was performed after TMAO administration. Injection of TMAO directly into the LSG was found to significantly increase the cardiac sympathetic tone and incidence of ventricular arrhythmias. In the systemic administration control arm, ventricular arrhythmias were also significantly increased.12

Increased inflammatory states appear to correlate with an increase in sympathetic tone and ventricular arrhythmias.12 In an animal study, direct injection of the proinflammatory factor IL-1Β into the LSG not only resulted in increased inflammation, but aggravated cardiac sympathetic remodeling. This led to a decreased effective refractory period and action potential duration, leading to an increased maximal slope of the restitution curve and higher occurrence of ventricular arrhythmias.41 Shi et al demonstrated that paraventricular nucleus microinjection with TNF-α and IL-1Β also enhanced the cardiac sympathetic afferent reflex, showing that these proinflammatory cytokines not only upregulate the inflammatory response, but can also have excitatory effects that stimulate sympathetic activity and have the potential to be proarrhythmic.19,42 Local and systemic administration of the gut microbe-derived TMAO increased the expression of IL-1Β and TNF-α, thus implicating the microbiome as a potential mediator of the inflammatory response and as another potential pathway for increased ventricular arrhythmias.12

The N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) is found in multiple organs—including the heart—but more specifically in the conducting system and myocardium.43,44 Research has discovered an upregulation of NMDARs in the setting of cardiac sympathetic hyperinnervation in rat models both with healed myocardial necrotic injury and without. The infusion of their ligand, NMDA, provoked ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation in rat models with sympathetic hyperinnervation and healed myocardial necrotic injury.45 Another study found that NMDAR activation provoked ventricular arrhythmias, but also prolonged repolarization and induced electrical instability.46 Proinflammatory markers have been shown to upregulate the expression of NMDARs; more importantly, NMDAR expression has been shown to be significantly increased in the setting of TMAO administration.12,47,48

5-HT also appears to have a substantial association with ventricular arrhythmias in addition to atrial arrhythmias. el-Mahdy demonstrated in anesthetized rats with acute coronary ligation that systemic doses of 5-HT represented a significant dose-dependent increase in the duration of ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation, while also increasing the number of ventricular ectopic beats.49 Certain gut microorganisms are known to produce 5-HT, including those in the genera Streptococcus, Escherichia, and Enterococcus.22 Additionally, oral ingestion of the Bifidobacterium infantis increased plasma levels of tryptophan in rat models.21 The gut microbiome may have significant effects on plasma serotonin levels, and thus have the potential to alter the risk for ventricular arrhythmias.

The deleterious effects of the gut microbiome have been documented. However, it appears to have potential protective effects, and several studies point to the possible mechanisms of this beneficial interaction. Propionate is a SCFA microorganism produced by gut microbial fermentation.50 In a rat model study, Zhou et al found that infusion of sodium propionate significantly reduced ventricular arrhythmias during acute myocardial ischemia or burst stimulation, thus confirming cardioprotective effects.50,51

Proposed mechanisms for reduced susceptibility to ventricular arrhythmias with propionate infusion include parasympathetic activation via the gut-brain axis, anti-inflammatory pathways, and improved cardiac electrophysiology instability.50 In addition butyrate has been found to reduce inflammation and myocardial hypertrophy. Jiang et al demonstrated in rats postmyocardial infarction that butyrate promoted expression of anti-inflammatory M2 macrophage markers, decreased expressions of nerve growth factor and norepinephrine, and decreased the density of nerve fibers for growth-associated protein-43 and tyrosine hydroxylase. The cumulative impact of butyrate led to suppression of inflammation and the inhibition of sympathetic neural remodeling, ultimately resulting in improved cardiac function and reduction in ventricular arrhythmias after myocardial infarction.52

Gut bacteria-derived acetate-mediated reduction in cardiac fibrosis may be another mechanism for the effects on ventricular arrhythmias. Cardiac fibrosis and scar are established as the primary substrate for reentrant ventricular arrhythmias seen in various cardiomyopathies.

Future Directions

The microbiome residing in the human gut has a significant impact on cardiac arrhythmias, the details of which remain unknown. A likely bidirectional relationship exists in which the gut microbiome may affect arrhythmogenesis and in turn be affected by cardiac arrhythmias. The mechanisms of action are not well understood, but likely involve the autonomic nervous system, inflammation, and metabolic pathways.

The gut microbiome is a complex collection of heterogenous microorganisms that have dramatic effects on the human body. Additional research is necessary to identify further associations and causations of gut microorganisms with various human body processes, as well as cardiovascular disease. The microbiome has been shown to directly and indirectly influence the development of different disease states, including the cardiovascular system and cardiac arrhythmias. Several pathways have been proposed through which the gut microbiome can potentially affect cardiac arrhythmogenesis. There are likely several mechanisms simultaneously in operation. Understanding the role of human gut microbiome in the genesis of cardiac arrhythmias not only may improve our understanding of arrhythmias, but also may result in novel treatment options. This could potentially lead to the development of therapeutic options and strategies to modulate the gut microbiome to help detect, prevent, and treat cardiac arrhythmias.

- Sharon G, Sampson TR, Geschwind DH, Mazmanian SK. The central nervous system and the gut microbiome. Cell. 2016;167(4):915-932. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.027

- Karlsson F, Tremaroli V, Nielsen J, Bäckhed F. Assessing the human gut microbiota in metabolic diseases. Diabetes. 2013;62(10):3341-3349. doi:10.2337/db13-0844

- Danneskiold-Samsøe NB, Dias de Freitas Queiroz Barros H, Santos R, et al. Interplay between food and gut microbiota in health and disease. Food Res Int. 2019;115:23-31. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2018.07.043

- Furusawa Y, Obata Y, Fukuda S, et al. Commensal microbe- derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature. 2013;504(7480):446-450. doi:10.1038/nature12721

- Integrative HMP (iHMP) Research Network Consortium. The integrative human microbiome project. Nature. 2019;569(7758):641-648. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1238-8

- Zubcevic J, Richards EM, Yang T, et al. Impaired autonomic nervous system-microbiome circuit in hypertension. Circ Res. 2019;125(1):104-116. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.313965

- Emoto T, Yamashita T, Sasaki N, et al. Analysis of gut microbiota in coronary artery disease patients: a possible link between gut microbiota and coronary artery disease. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2016;23(8):908-921. doi:10.5551/jat.32672

- Zuo K, Li J, Li K, et al. Disordered gut microbiota and alterations in metabolic patterns are associated with atrial fibrillation. Gigascience. 2019;8(6):giz058. doi:10.1093/gigascience/giz058

- Li J, Zhao F, Wang Y, et al. Gut microbiota dysbiosis contributes to the development of hypertension. Microbiome. 2017;5(1):14. doi:10.1186/s40168-016-0222-x

- Qin J, Li Y, Cai Z, et al. A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2012;490(7418):55-60. doi:10.1038/nature11450

- Chang CJ, Lin CS, Lu CC, et al. Ganoderma lucidum reduces obesity in mice by modulating the composition of the gut microbiota. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7489. doi:10.1038/ncomms8489

- Meng G, Zhou X, Wang M, et al. Gut microbederived metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide activates the cardiac autonomic nervous system and facilitates ischemia-induced ventricular arrhythmia via two different pathways. EBioMedicine. 2019;44:656-664. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.03.066

- Yoshida N, Emoto T, Yamashita T, et al. Bacteroides vulgatus and Bacteroides dorei reduce gut microbial lipopolysaccharide production and inhibit atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2018;138(22):2486-2498. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.033714

- Cussotto S, Sandhu KV, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. The neuroendocrinology of the microbiota-gut-brain axis: a behavioural perspective. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2018;51:80-101. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2018.04.002

- Dinan TG, Stilling RM, Stanton C, Cryan JF. Collective unconscious: how gut microbes shape human behavior. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;63:1-9. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.02.021

- Muller PA, Schneeberger M, Matheis F, et al. Microbiota modulate sympathetic neurons via a gutbrain circuit. Nature. 2020;583(7816):441-446. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2474-7

- Ohira H, Tsutsui W, Fujioka Y. Are short chain fatty acids in gut microbiota defensive players for inflammation and atherosclerosis? J Atheroscler Thromb. 2017;24(7):660-672. doi:10.5551/jat.RV17006

- Aguilar EC, Leonel AJ, Teixeira LG, et al. Butyrate impairs atherogenesis by reducing plaque inflammation and vulnerability and decreasing NFêB activation. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;24(6):606-613. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2014.01.002

- Wei SG, Yu Y, Zhang ZH, Felder RB. Proinflammatory cytokines upregulate sympathoexcit - atory mechanisms in the subfornical organ of the rat. Hypertension. 2015;65(5):1126-1133. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.05112

- Dinan TG, Stanton C, Cryan JF. Psychobiotics: a novel class of psychotropic. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74(10):720- 726. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.05.001

- Desbonnet L, Garrett L, Clarke G, Bienenstock J, Dinan TG. The probiotic Bifidobacteria infantis: an assessment of potential antidepressant properties in the rat. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;43(2):164-174. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.03.009

- Lyte M. Probiotics function mechanistically as delivery vehicles for neuroactive compounds: microbial endocrinology in the design and use of probiotics. Bioessays. 2011;33(8):574-581. doi:10.1002/bies.201100024

- Yusuf S, Al-Saady N, Camm AJ. 5-hydroxytryptamine and atrial fibrillation: how significant is this piece in the puzzle? J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2003;14(2):209-214. doi:10.1046/j.1540-8167.2003.02381.x

- Marques FZ, Nelson E, Chu PY, et al. High-fiber diet and acetate supplementation change the gut microbiota and prevent the development of hypertension and heart failure in hypertensive mice. Circulation. 2017;135(10):964-977. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024545

- Björkegren JLM, Lusis AJ. Atherosclerosis: recent developments. Cell. 2022;185(10):1630-1645. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2022.04.004

- Tang WHW, Bäckhed F, Landmesser U, Hazen SL. Intestinal microbiota in cardiovascular health and disease: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(16):2089-2105. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.024

- Jie Z, Xia H, Zhong SL, et al. The gut microbiome in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):845. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00900-1

- Kasahara K, Krautkramer KA, Org E, et al. Interactions between Roseburia intestinalis and diet modulate atherogenesis in a murine model. Nat Microbiol. 2018;3(12):1461- 1471. doi:10.1038/s41564-018-0272-x

- Roberts AB, Gu X, Buffa JA, et al. Development of a gut microbe-targeted nonlethal therapeutic to inhibit thrombosis potential. Nat Med. 2018;24(9):1407-1417. doi:10.1038/s41591-018-0128-1

- Yu L, Meng G, Huang B, et al. A potential relationship between gut microbes and atrial fibrillation: trimethylamine N-oxide, a gut microbe-derived metabolite, facilitates the progression of atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol. 2018;255:92- 98. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.11.071

- Okazaki R, Iwasaki YK, Miyauchi Y, et al. Lipopolysaccharide induces atrial arrhythmogenesis via down-regulation of L-type Ca2+ channel genes in rats. Int Heart J. 2009;50(3):353-363. doi:10.1536/ihj.50.353

- Chen WT, Chen YC, Hsieh MH, et al. The uremic toxin indoxyl sulfate increases pulmonary vein and atrial arrhythmogenesis. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2015;26(2):203- 210. doi:10.1111/jce.12554

- Fretts AM, Mozaffarian D, Siscovick DS, et al. Plasma phospholipid saturated fatty acids and incident atrial fibrillation: the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(3):e000889. doi:10.1161/JAHA.114.000889

- Horas HNS, Nishiumi S, Kawano Y, Kobayashi T, Yoshida M, Azuma T. Adrenic acid as an inflammation enhancer in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2017;623-624:64-75. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2017.04.009

- Tabata T, Yamashita T, Hosomi K, et al. Gut microbial composition in patients with atrial fibrillation: effects of diet and drugs. Heart Vessels. 2021;36(1):105-114. doi:10.1007/s00380-020-01669-y

- López-Rodriguez ML, Benhamú B, Morcillo MJ, et al. 5-HT(4) receptor antagonists: structure-affinity relationships and ligand-receptor interactions. Curr Top Med Chem. 2002;2(6):625-641. doi:10.2174/1568026023393769

- Yu L, Zhou L, Cao G, et al. Optogenetic modulation of cardiac sympathetic nerve activity to prevent ventricular arrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(22):2778-2790. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.09.1107

- Schwartz PJ, Vanoli E. Cardiac arrhythmias elicited by interaction between acute myocardial ischemia and sympathetic hyperactivity: a new experimental model for the study of antiarrhythmic drugs. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1981;3(6):1251-1259. doi:10.1097/00005344-198111000-00012

- Puddu PE, Jouve R, Langlet F, Guillen JC, Lanti M, Reale A. Prevention of postischemic ventricular fibrillation late after right or left stellate ganglionectomy in dogs. Circulation. 1988;77(4):935-946. doi:10.1161/01.cir.77.4.935

- Vaseghi M, Gima J, Kanaan C, et al. Cardiac sympathetic denervation in patients with refractory ventricular arrhythmias or electrical storm: intermediate and longterm follow-up. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11(3):360-366. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.11.028

- Wang M, Li S, Zhou X, et al. Increased inflammation promotes ventricular arrhythmia through aggravating left stellate ganglion remodeling in a canine ischemia model. Int J Cardiol. 2017;248:286-293. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.08.011

- Shi Z, Gan XB, Fan ZD, et al. Inflammatory cytokines in paraventricular nucleus modulate sympathetic activity and cardiac sympathetic afferent reflex in rats. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2011;203(2):289-297. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1716.2011.02313.x

- Gill S, Veinot J, Kavanagh M, Pulido O. Human heart glutamate receptors - implications for toxicology, food safety, and drug discovery. Toxicol Pathol. 2007;35(3):411-417. doi:10.1080/01926230701230361

- Govoruskina N, Jakovljevic V, Zivkovic V, et al. The role of cardiac N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in heart conditioning— effects on heart function and oxidative stress. Biomolecules. 2020;10(7):1065. doi:10.3390/biom10071065

- Lü J, Gao X, Gu J, et al. Nerve sprouting contributes to increased severity of ventricular tachyarrhythmias by upregulating iGluRs in rats with healed myocardial necrotic injury. J Mol Neurosci. 2012;48(2):448-455. doi:10.1007/s12031-012-9720-x

- Shi S, Liu T, Li Y, et al. Chronic N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor activation induces cardiac electrical remodeling and increases susceptibility to ventricular arrhythmias. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2014;37(10):1367-1377. doi:10.1111/pace.12430

- Zhang Z, Bassam B, Thomas AG, et al. Maternal inflammation leads to impaired glutamate homeostasis and upregulation of glutamate carboxypeptidase II in activated microglia in the fetal/newborn rabbit brain. Neurobiol Dis. 2016;94:116-128. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2016.06.010

- Wu LJ, Toyoda H, Zhao MG, et al. Upregulation of forebrain NMDA NR2B receptors contributes to behavioral sensitization after inflammation. J Neurosci. 2005;25(48):11107-11116. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1678-05.2005

- el-Mahdy SA. 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) enhances ventricular arrhythmias induced by acute coronary artery ligation in rats. Res Commun Chem Pathol Pharmacol. 1990;68(3):383-386.

- Zhou M, Li D, Xie K, et al. The short-chain fatty acid propionate improved ventricular electrical remodeling in a rat model with myocardial infarction. Food Funct. 2021;12(24):12580-12593. doi:10.1039/d1fo02040d

- Bartolomaeus H, Balogh A, Yakoub M, et al. Short-chain fatty acid propionate protects from hypertensive cardiovascular damage. Circulation. 2019;139(11):1407-1421. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.036652

- Jiang X, Huang X, Tong Y, Gao H. Butyrate improves cardiac function and sympathetic neural remodeling following myocardial infarction in rats. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2020;98(6):391-399. doi:10.1139/cjpp-2019-0531

- Sharon G, Sampson TR, Geschwind DH, Mazmanian SK. The central nervous system and the gut microbiome. Cell. 2016;167(4):915-932. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.027

- Karlsson F, Tremaroli V, Nielsen J, Bäckhed F. Assessing the human gut microbiota in metabolic diseases. Diabetes. 2013;62(10):3341-3349. doi:10.2337/db13-0844

- Danneskiold-Samsøe NB, Dias de Freitas Queiroz Barros H, Santos R, et al. Interplay between food and gut microbiota in health and disease. Food Res Int. 2019;115:23-31. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2018.07.043

- Furusawa Y, Obata Y, Fukuda S, et al. Commensal microbe- derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature. 2013;504(7480):446-450. doi:10.1038/nature12721

- Integrative HMP (iHMP) Research Network Consortium. The integrative human microbiome project. Nature. 2019;569(7758):641-648. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1238-8

- Zubcevic J, Richards EM, Yang T, et al. Impaired autonomic nervous system-microbiome circuit in hypertension. Circ Res. 2019;125(1):104-116. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.313965

- Emoto T, Yamashita T, Sasaki N, et al. Analysis of gut microbiota in coronary artery disease patients: a possible link between gut microbiota and coronary artery disease. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2016;23(8):908-921. doi:10.5551/jat.32672

- Zuo K, Li J, Li K, et al. Disordered gut microbiota and alterations in metabolic patterns are associated with atrial fibrillation. Gigascience. 2019;8(6):giz058. doi:10.1093/gigascience/giz058

- Li J, Zhao F, Wang Y, et al. Gut microbiota dysbiosis contributes to the development of hypertension. Microbiome. 2017;5(1):14. doi:10.1186/s40168-016-0222-x

- Qin J, Li Y, Cai Z, et al. A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2012;490(7418):55-60. doi:10.1038/nature11450

- Chang CJ, Lin CS, Lu CC, et al. Ganoderma lucidum reduces obesity in mice by modulating the composition of the gut microbiota. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7489. doi:10.1038/ncomms8489

- Meng G, Zhou X, Wang M, et al. Gut microbederived metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide activates the cardiac autonomic nervous system and facilitates ischemia-induced ventricular arrhythmia via two different pathways. EBioMedicine. 2019;44:656-664. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.03.066

- Yoshida N, Emoto T, Yamashita T, et al. Bacteroides vulgatus and Bacteroides dorei reduce gut microbial lipopolysaccharide production and inhibit atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2018;138(22):2486-2498. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.033714

- Cussotto S, Sandhu KV, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. The neuroendocrinology of the microbiota-gut-brain axis: a behavioural perspective. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2018;51:80-101. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2018.04.002

- Dinan TG, Stilling RM, Stanton C, Cryan JF. Collective unconscious: how gut microbes shape human behavior. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;63:1-9. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.02.021

- Muller PA, Schneeberger M, Matheis F, et al. Microbiota modulate sympathetic neurons via a gutbrain circuit. Nature. 2020;583(7816):441-446. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2474-7

- Ohira H, Tsutsui W, Fujioka Y. Are short chain fatty acids in gut microbiota defensive players for inflammation and atherosclerosis? J Atheroscler Thromb. 2017;24(7):660-672. doi:10.5551/jat.RV17006

- Aguilar EC, Leonel AJ, Teixeira LG, et al. Butyrate impairs atherogenesis by reducing plaque inflammation and vulnerability and decreasing NFêB activation. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;24(6):606-613. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2014.01.002

- Wei SG, Yu Y, Zhang ZH, Felder RB. Proinflammatory cytokines upregulate sympathoexcit - atory mechanisms in the subfornical organ of the rat. Hypertension. 2015;65(5):1126-1133. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.05112

- Dinan TG, Stanton C, Cryan JF. Psychobiotics: a novel class of psychotropic. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74(10):720- 726. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.05.001

- Desbonnet L, Garrett L, Clarke G, Bienenstock J, Dinan TG. The probiotic Bifidobacteria infantis: an assessment of potential antidepressant properties in the rat. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;43(2):164-174. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.03.009

- Lyte M. Probiotics function mechanistically as delivery vehicles for neuroactive compounds: microbial endocrinology in the design and use of probiotics. Bioessays. 2011;33(8):574-581. doi:10.1002/bies.201100024

- Yusuf S, Al-Saady N, Camm AJ. 5-hydroxytryptamine and atrial fibrillation: how significant is this piece in the puzzle? J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2003;14(2):209-214. doi:10.1046/j.1540-8167.2003.02381.x

- Marques FZ, Nelson E, Chu PY, et al. High-fiber diet and acetate supplementation change the gut microbiota and prevent the development of hypertension and heart failure in hypertensive mice. Circulation. 2017;135(10):964-977. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024545

- Björkegren JLM, Lusis AJ. Atherosclerosis: recent developments. Cell. 2022;185(10):1630-1645. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2022.04.004

- Tang WHW, Bäckhed F, Landmesser U, Hazen SL. Intestinal microbiota in cardiovascular health and disease: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(16):2089-2105. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.024

- Jie Z, Xia H, Zhong SL, et al. The gut microbiome in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):845. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00900-1

- Kasahara K, Krautkramer KA, Org E, et al. Interactions between Roseburia intestinalis and diet modulate atherogenesis in a murine model. Nat Microbiol. 2018;3(12):1461- 1471. doi:10.1038/s41564-018-0272-x

- Roberts AB, Gu X, Buffa JA, et al. Development of a gut microbe-targeted nonlethal therapeutic to inhibit thrombosis potential. Nat Med. 2018;24(9):1407-1417. doi:10.1038/s41591-018-0128-1

- Yu L, Meng G, Huang B, et al. A potential relationship between gut microbes and atrial fibrillation: trimethylamine N-oxide, a gut microbe-derived metabolite, facilitates the progression of atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol. 2018;255:92- 98. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.11.071

- Okazaki R, Iwasaki YK, Miyauchi Y, et al. Lipopolysaccharide induces atrial arrhythmogenesis via down-regulation of L-type Ca2+ channel genes in rats. Int Heart J. 2009;50(3):353-363. doi:10.1536/ihj.50.353

- Chen WT, Chen YC, Hsieh MH, et al. The uremic toxin indoxyl sulfate increases pulmonary vein and atrial arrhythmogenesis. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2015;26(2):203- 210. doi:10.1111/jce.12554

- Fretts AM, Mozaffarian D, Siscovick DS, et al. Plasma phospholipid saturated fatty acids and incident atrial fibrillation: the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(3):e000889. doi:10.1161/JAHA.114.000889

- Horas HNS, Nishiumi S, Kawano Y, Kobayashi T, Yoshida M, Azuma T. Adrenic acid as an inflammation enhancer in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2017;623-624:64-75. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2017.04.009

- Tabata T, Yamashita T, Hosomi K, et al. Gut microbial composition in patients with atrial fibrillation: effects of diet and drugs. Heart Vessels. 2021;36(1):105-114. doi:10.1007/s00380-020-01669-y

- López-Rodriguez ML, Benhamú B, Morcillo MJ, et al. 5-HT(4) receptor antagonists: structure-affinity relationships and ligand-receptor interactions. Curr Top Med Chem. 2002;2(6):625-641. doi:10.2174/1568026023393769

- Yu L, Zhou L, Cao G, et al. Optogenetic modulation of cardiac sympathetic nerve activity to prevent ventricular arrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(22):2778-2790. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.09.1107

- Schwartz PJ, Vanoli E. Cardiac arrhythmias elicited by interaction between acute myocardial ischemia and sympathetic hyperactivity: a new experimental model for the study of antiarrhythmic drugs. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1981;3(6):1251-1259. doi:10.1097/00005344-198111000-00012

- Puddu PE, Jouve R, Langlet F, Guillen JC, Lanti M, Reale A. Prevention of postischemic ventricular fibrillation late after right or left stellate ganglionectomy in dogs. Circulation. 1988;77(4):935-946. doi:10.1161/01.cir.77.4.935

- Vaseghi M, Gima J, Kanaan C, et al. Cardiac sympathetic denervation in patients with refractory ventricular arrhythmias or electrical storm: intermediate and longterm follow-up. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11(3):360-366. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.11.028

- Wang M, Li S, Zhou X, et al. Increased inflammation promotes ventricular arrhythmia through aggravating left stellate ganglion remodeling in a canine ischemia model. Int J Cardiol. 2017;248:286-293. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.08.011

- Shi Z, Gan XB, Fan ZD, et al. Inflammatory cytokines in paraventricular nucleus modulate sympathetic activity and cardiac sympathetic afferent reflex in rats. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2011;203(2):289-297. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1716.2011.02313.x

- Gill S, Veinot J, Kavanagh M, Pulido O. Human heart glutamate receptors - implications for toxicology, food safety, and drug discovery. Toxicol Pathol. 2007;35(3):411-417. doi:10.1080/01926230701230361

- Govoruskina N, Jakovljevic V, Zivkovic V, et al. The role of cardiac N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in heart conditioning— effects on heart function and oxidative stress. Biomolecules. 2020;10(7):1065. doi:10.3390/biom10071065