User login

Smooth Symmetric Plaques on the Face, Trunk, and Extremities

Smooth Symmetric Plaques on the Face, Trunk, and Extremities

THE DIAGNOSIS: Lepromatous Leprosy

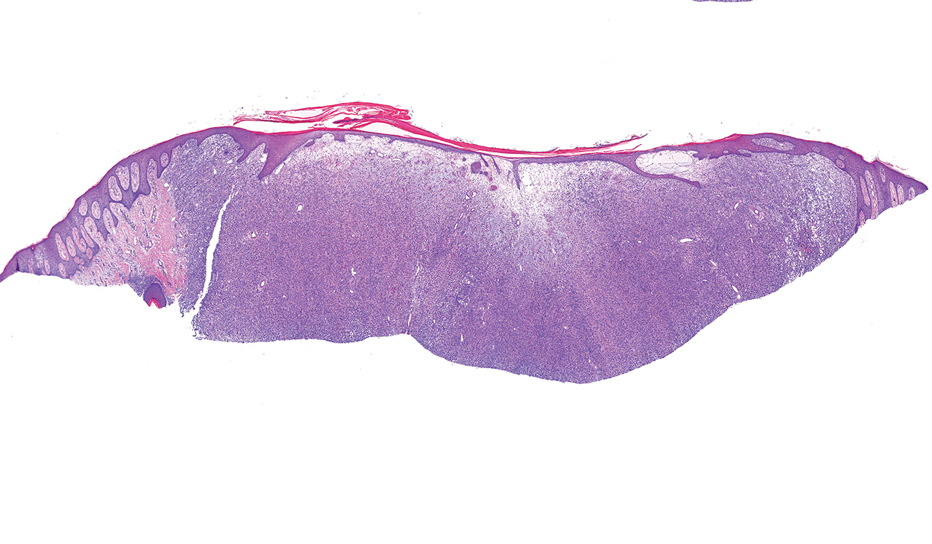

Histopathology showed collections of epithelioid to sarcoidal granulomas throughout the dermis and clustered around nerve bundles with a grenz zone at the dermoepidermal junction. Fite stain was positive for acid-fast bacteria, which were confirmed to be Mycobacterium leprae by by the National Hansen’s Disease program. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of lepromatous leprosy (LL) was made. The patient was treated by the infectious disease department with multidrug therapy that included monthly rifampin, moxifloxacin, and minocycline; weekly methotrexate with daily folic acid; and an extended prednisone taper with prophylactic cholecalciferol.

Lepromatous leprosy is characterized by high antibody titers to the acid-fast, gram-positive bacillus Mycobacterium leprae as well as a high bacillary load.1 Patients typically present with muscle weakness, anesthetic skin patches, and claw hands. Patients also may present with foot drop, ulcerations of the hands and feet, autonomic dysfunction with anhidrosis or impaired sweating, and localized alopecia.2 Over months to years, LL may progress to extensive sensory loss and indurated lesions that infiltrate the skin and cause thickening, especially on the face (known as leonine facies). Furthermore, LL is characterized by extensive bilaterally symmetric cutaneous lesions with poorly defined borders and raised indurated centers.3

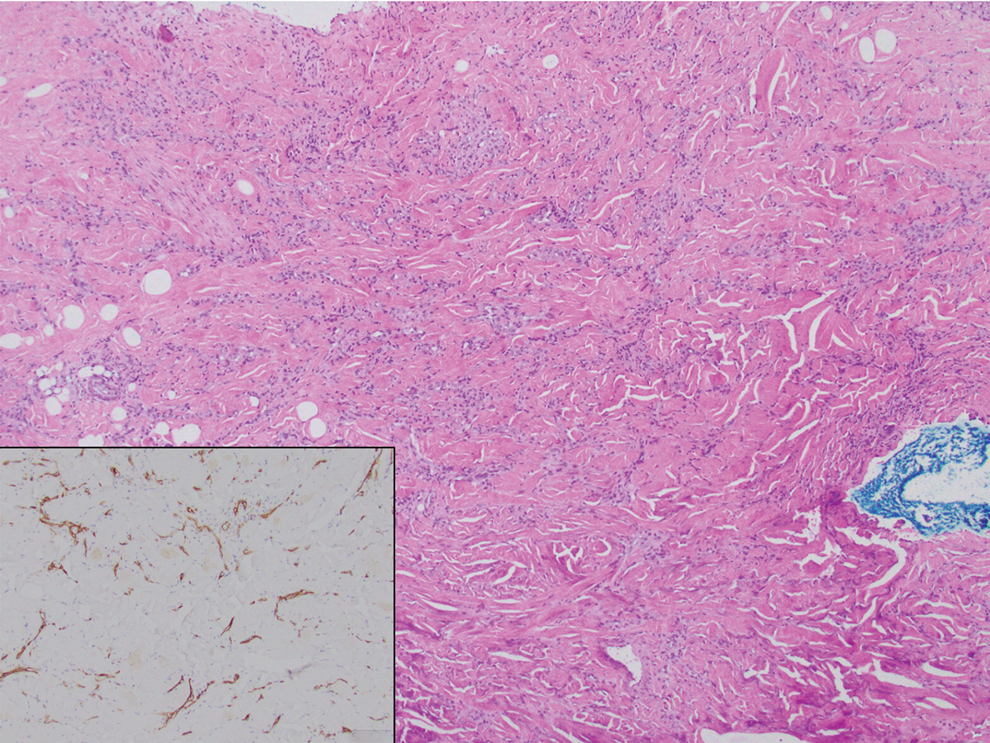

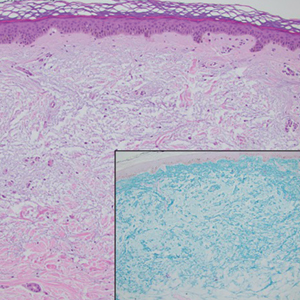

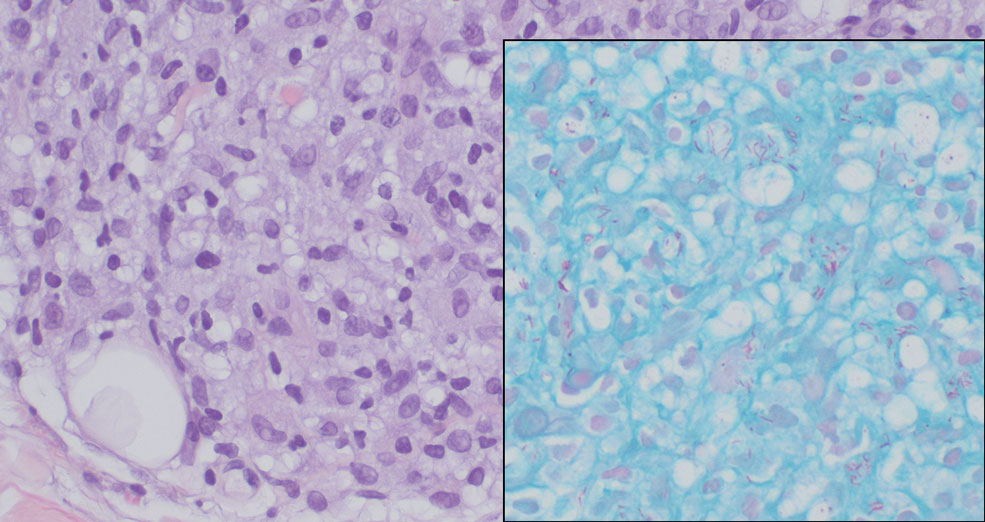

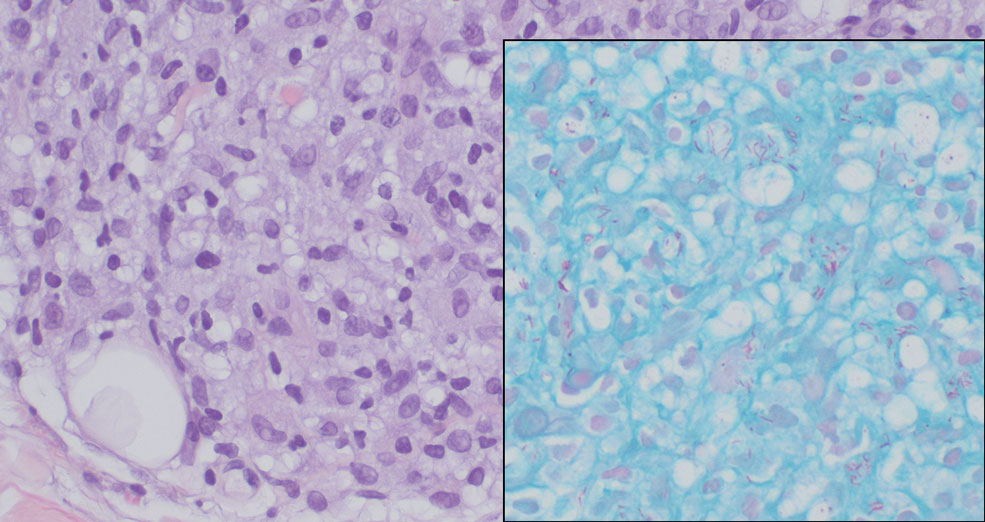

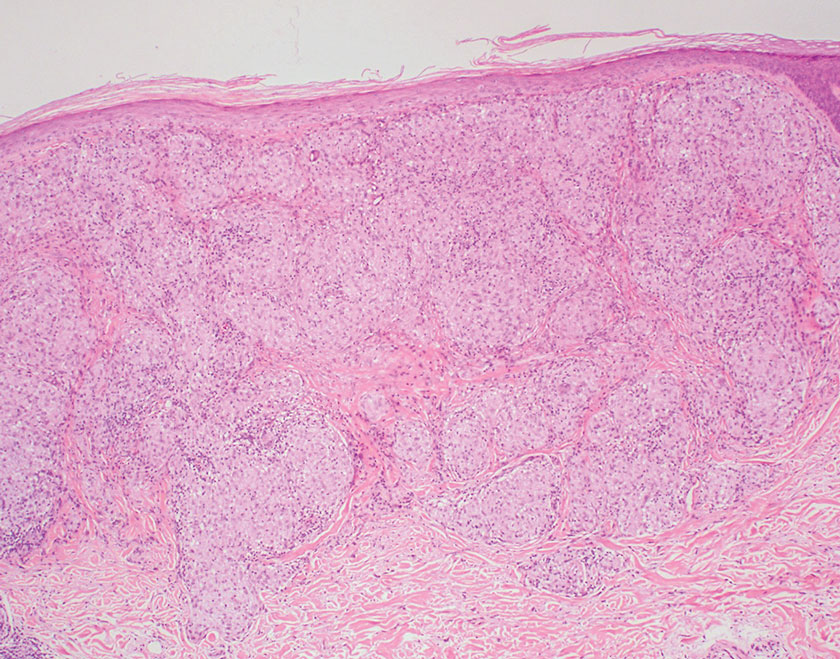

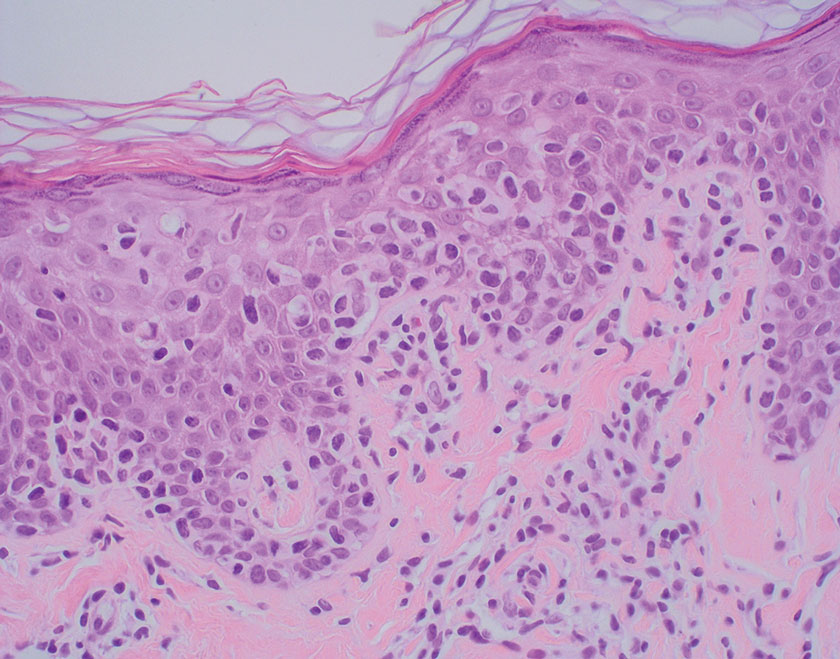

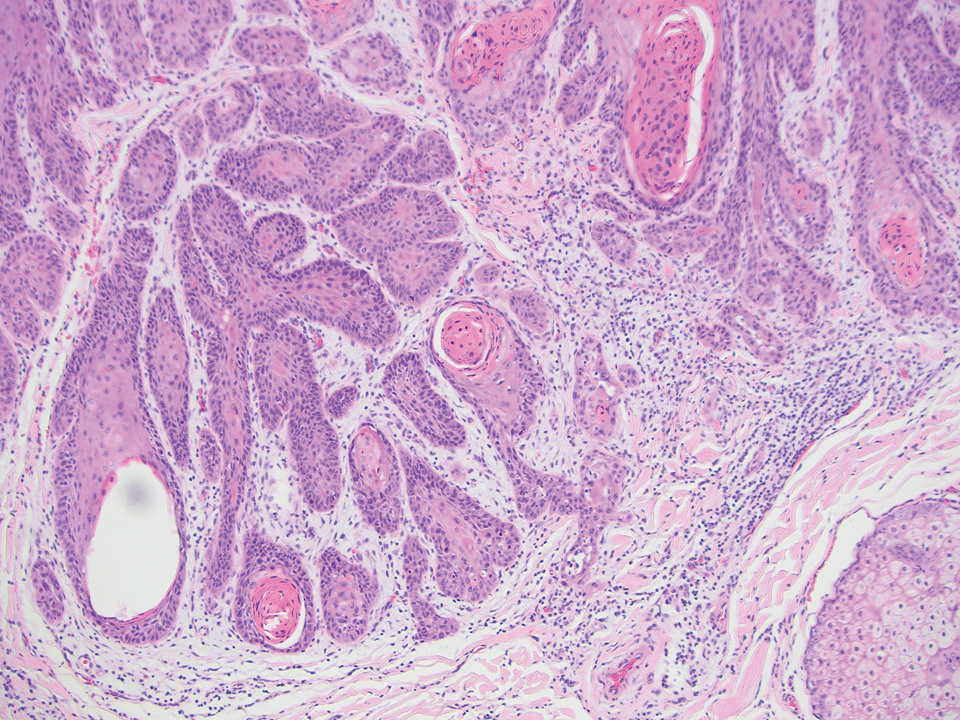

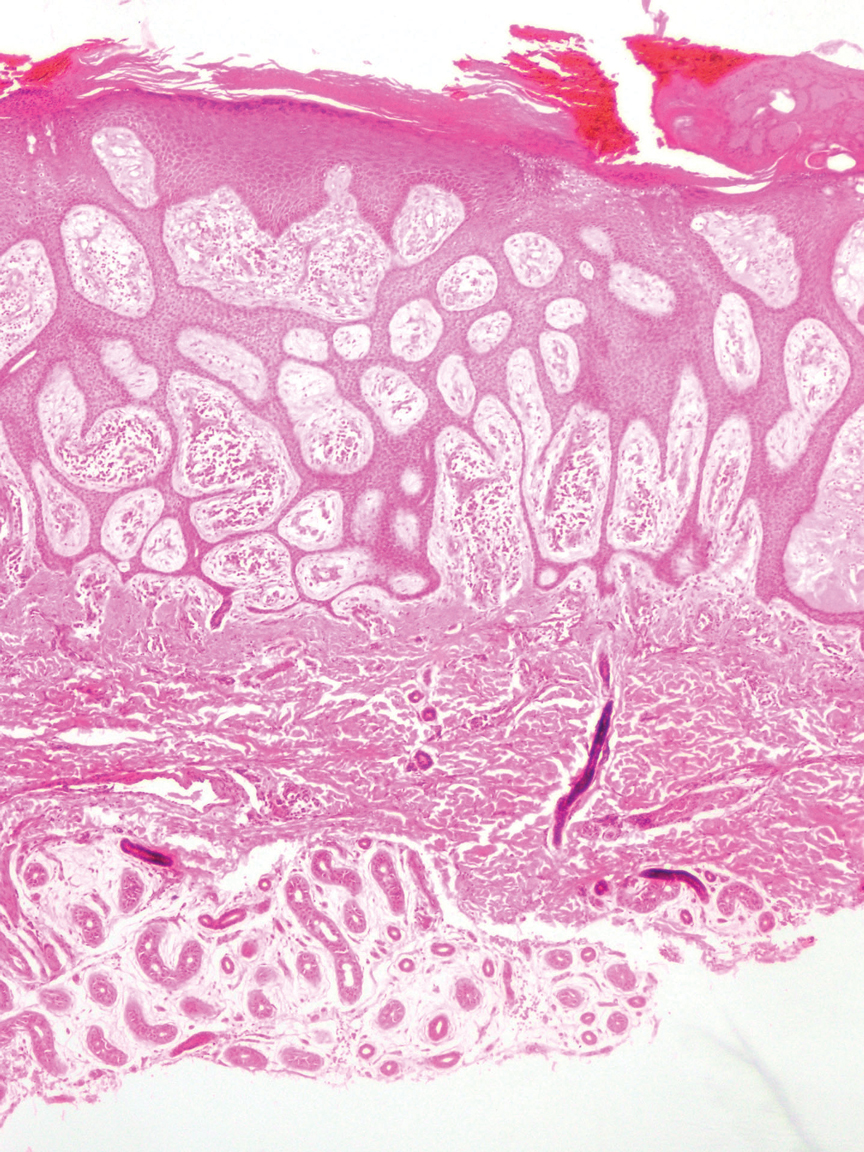

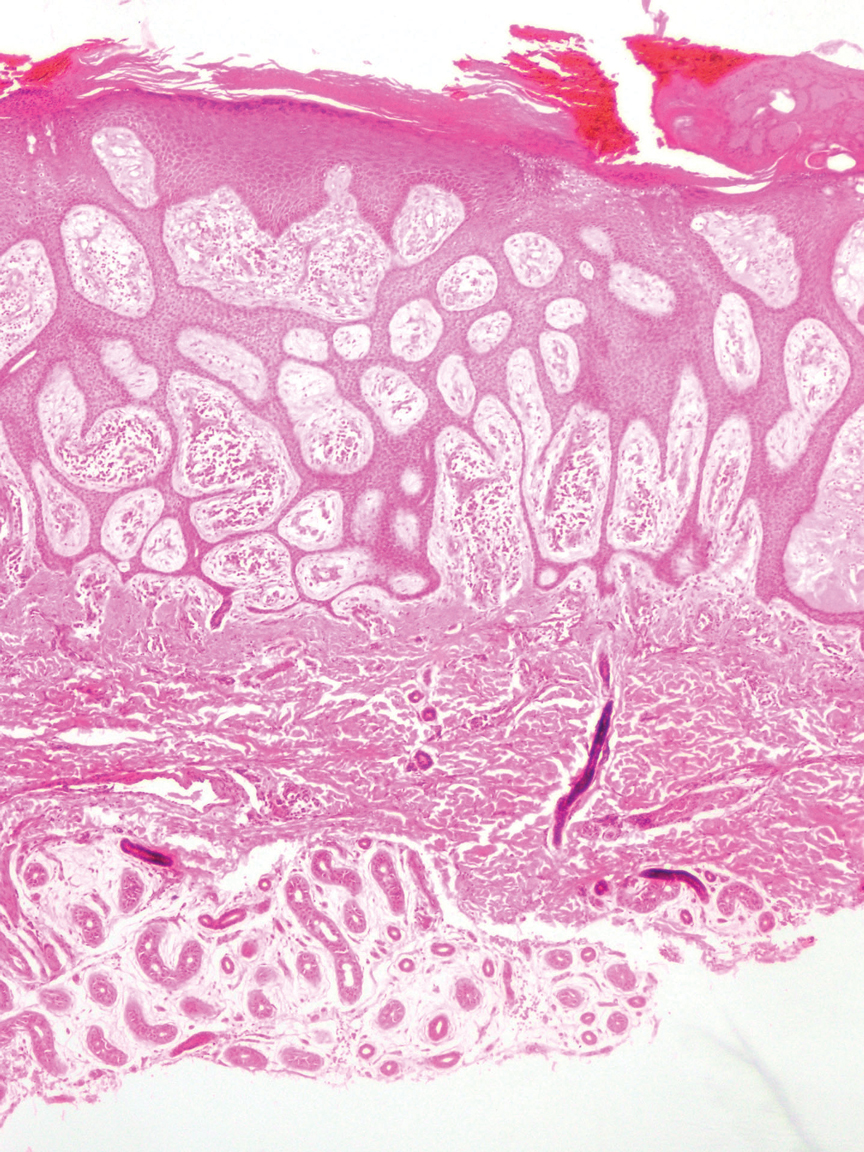

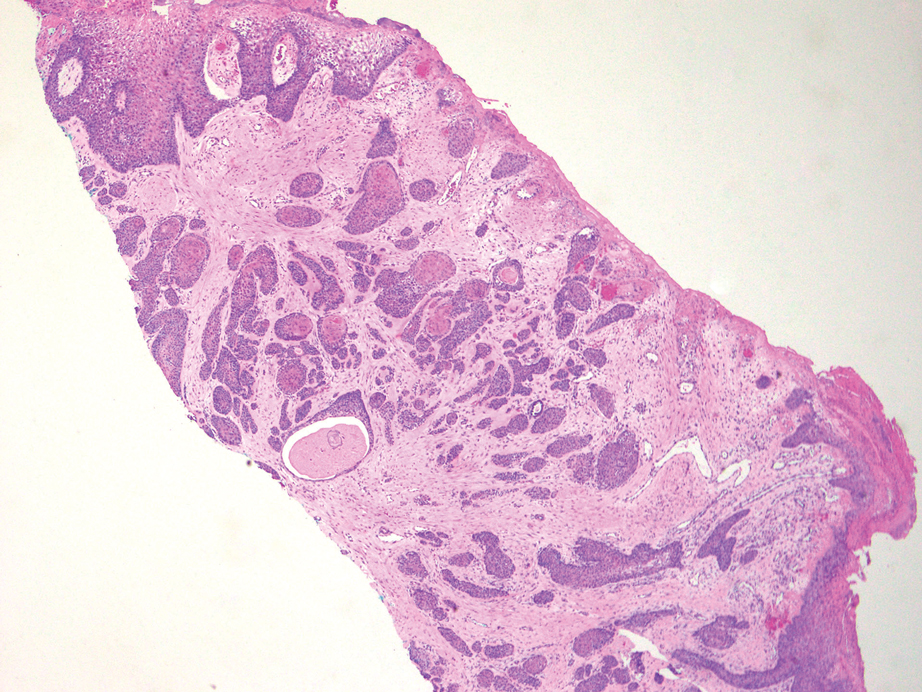

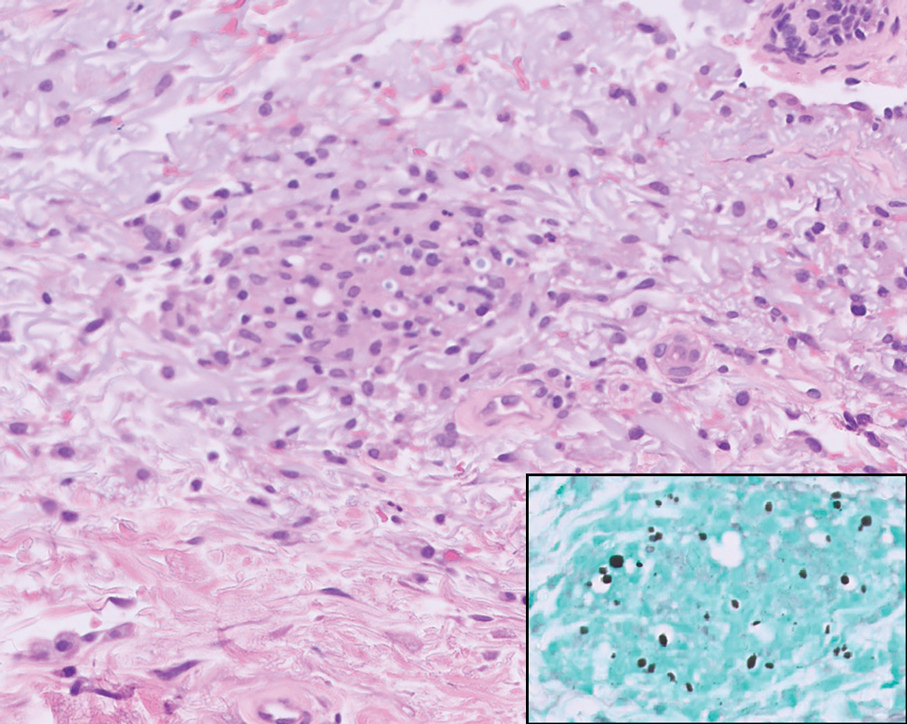

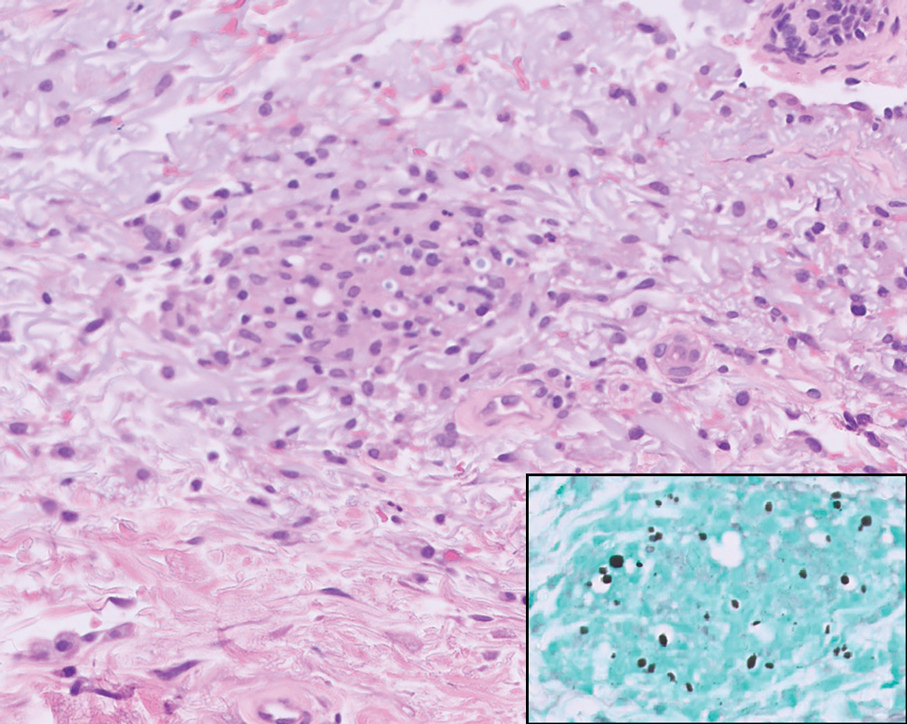

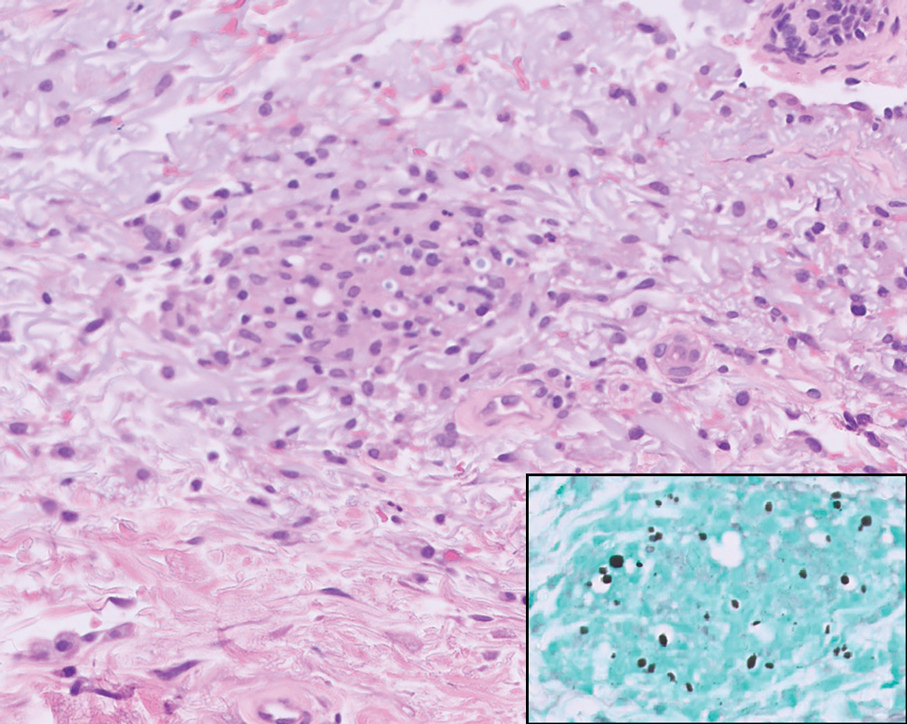

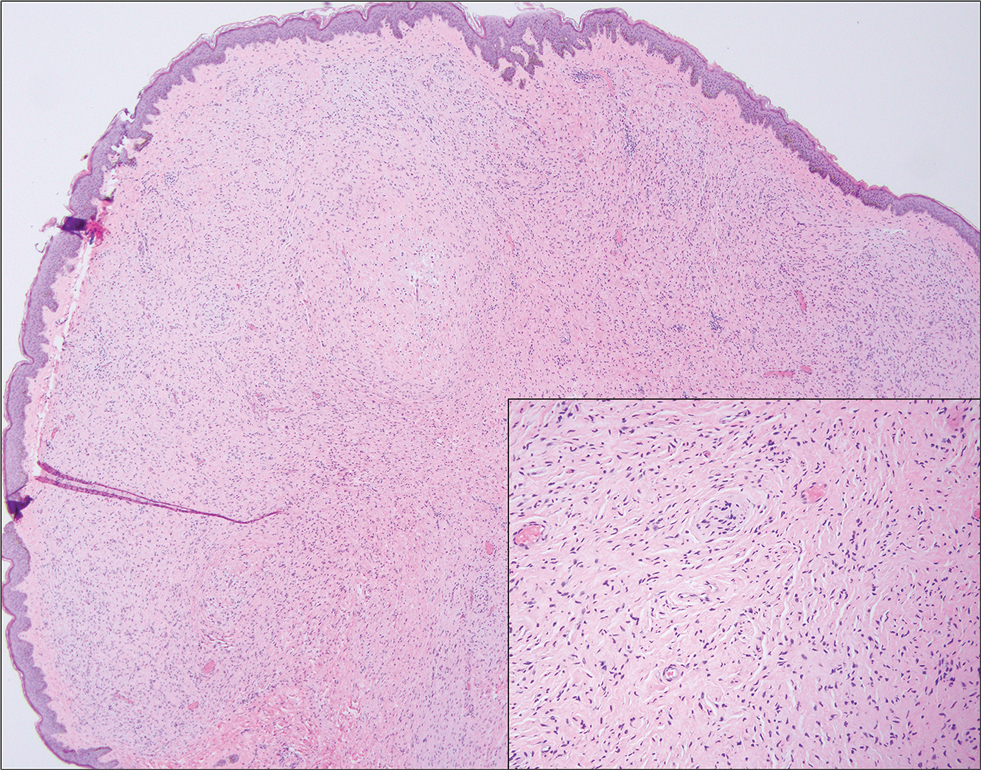

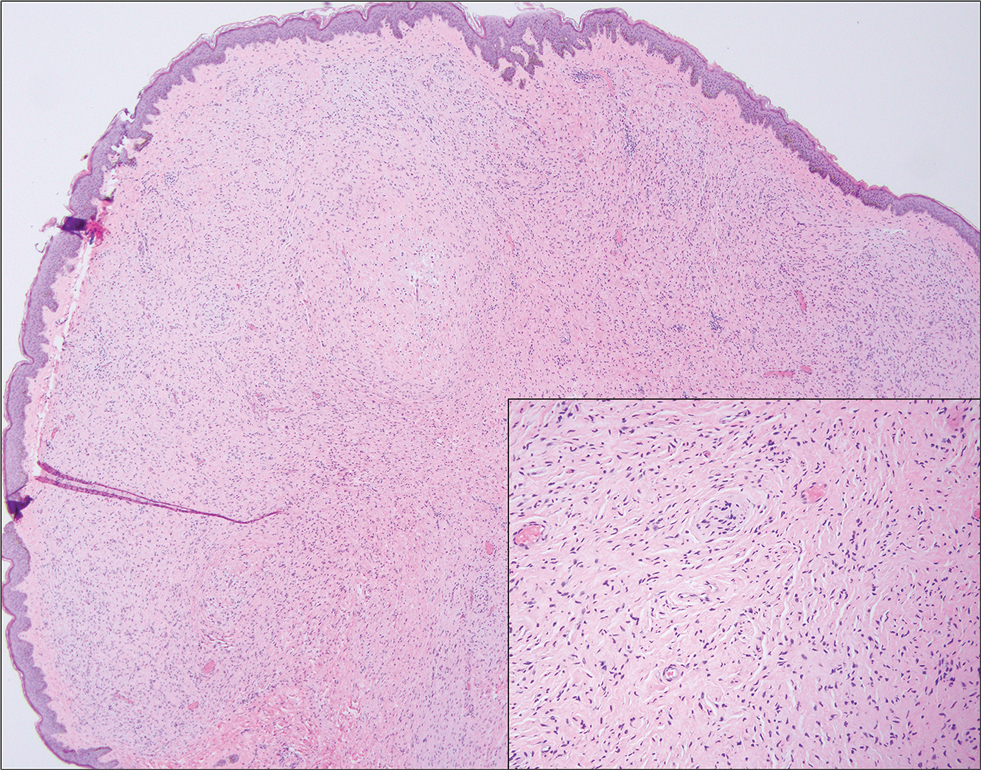

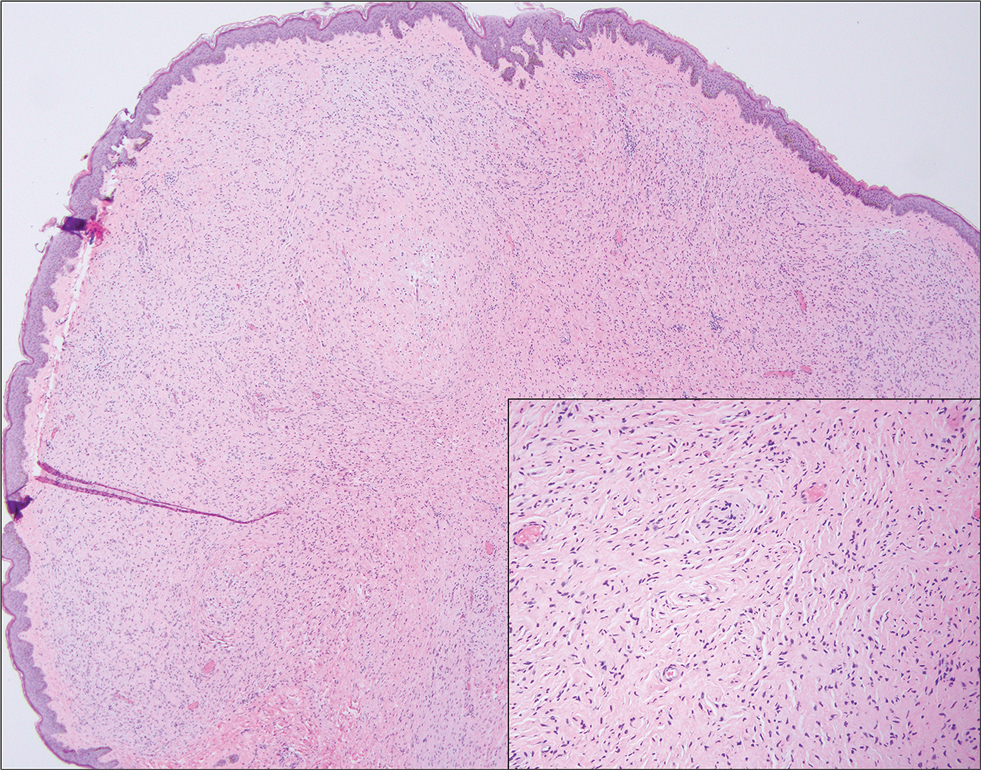

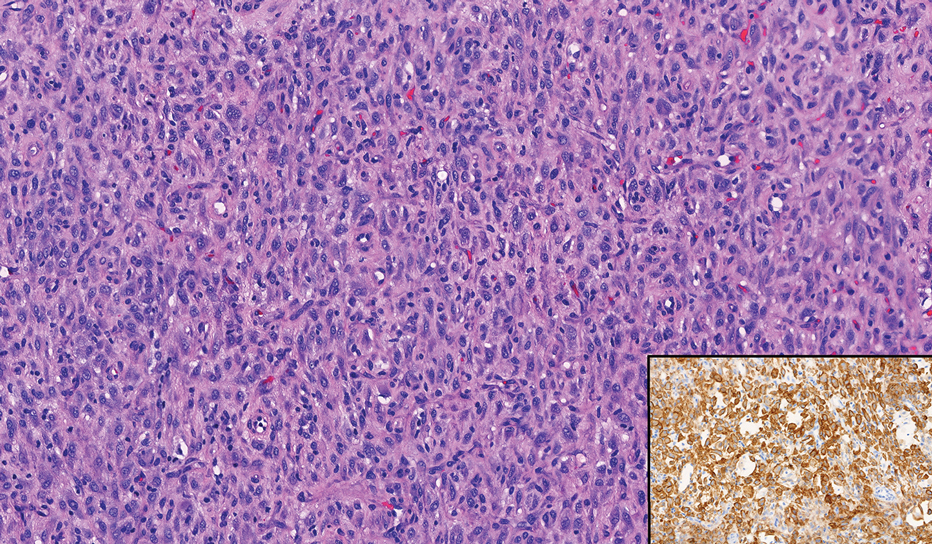

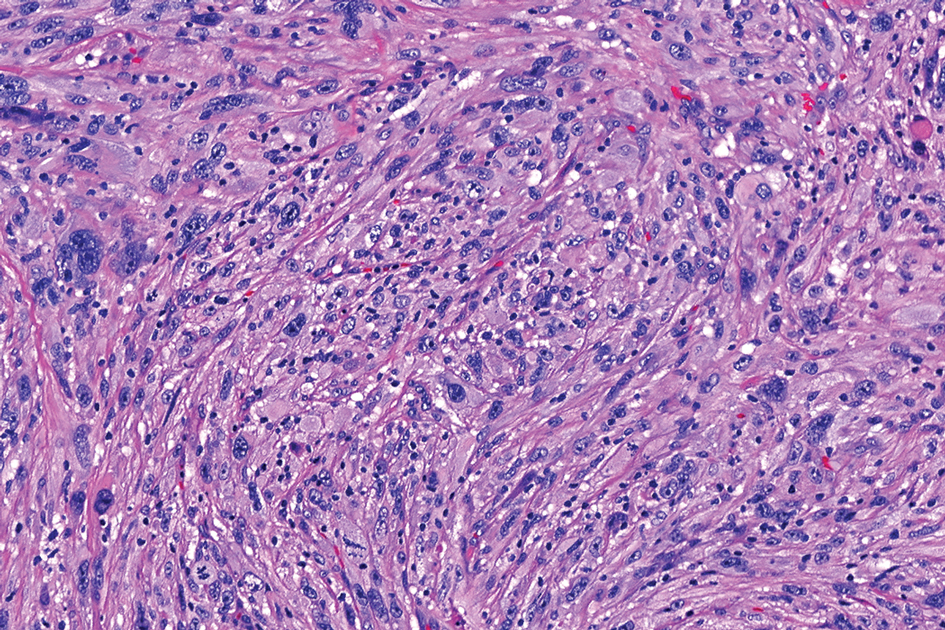

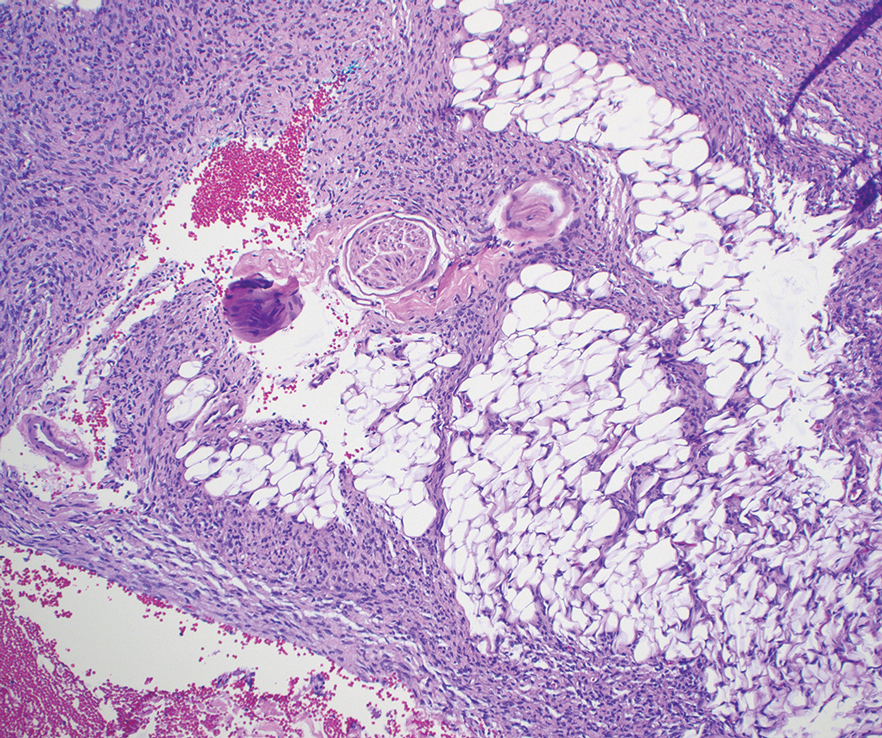

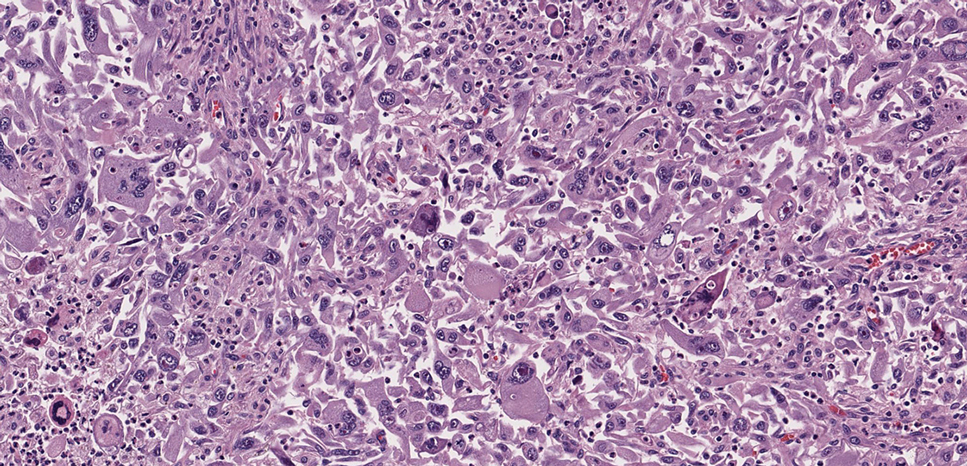

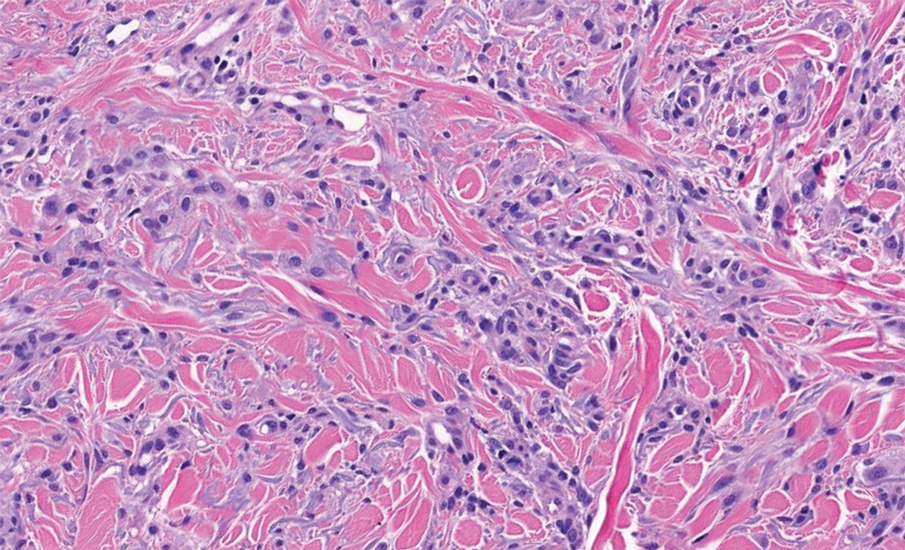

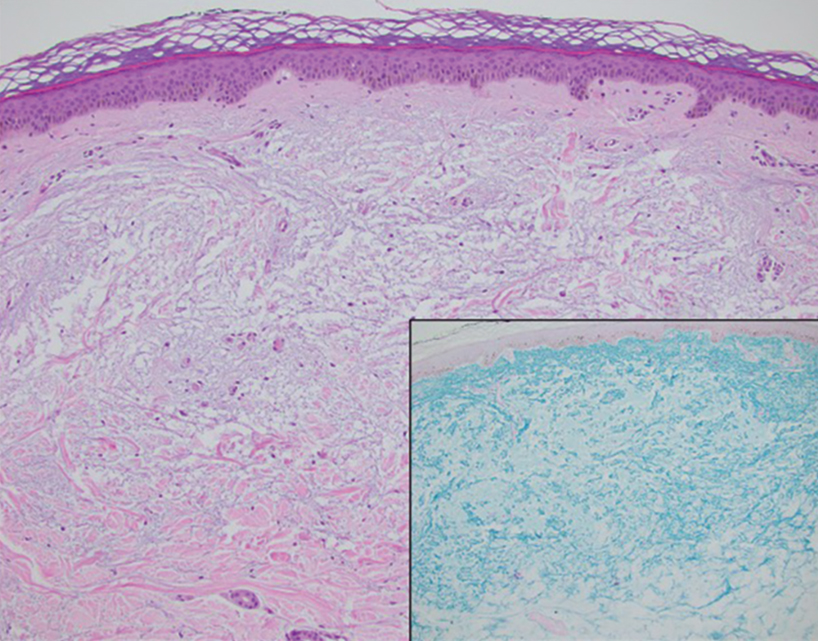

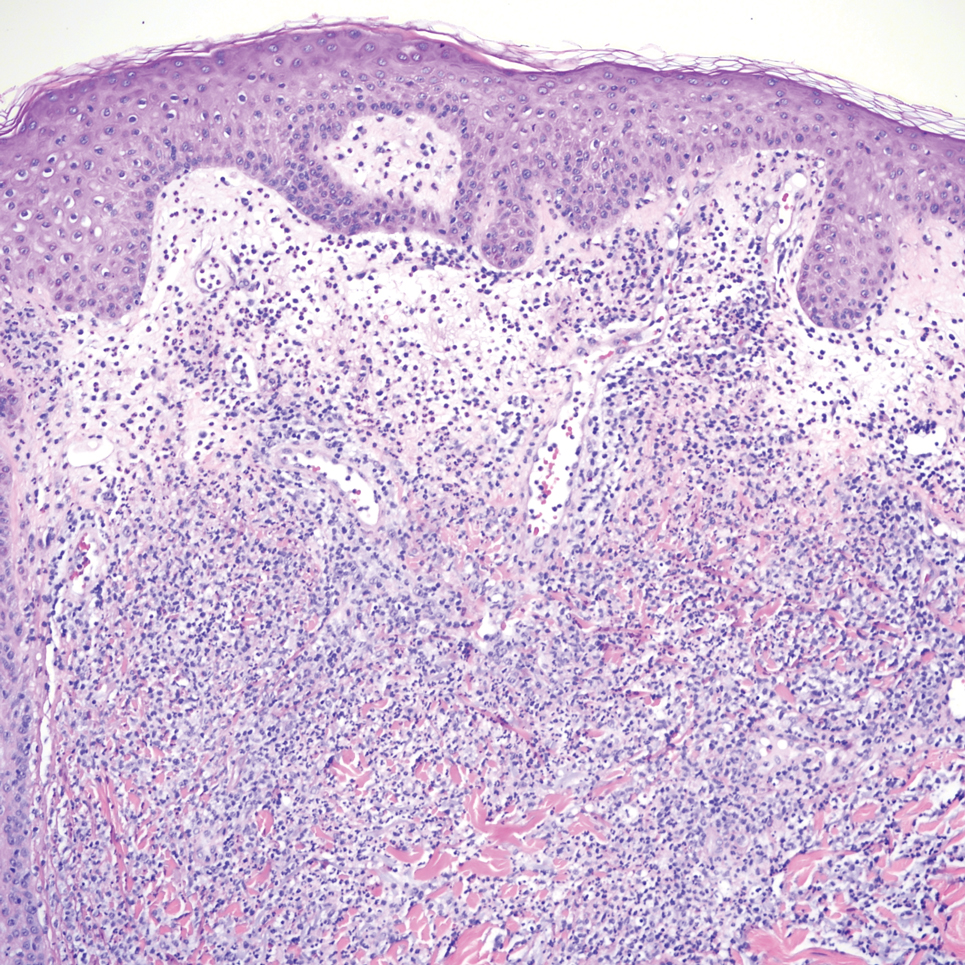

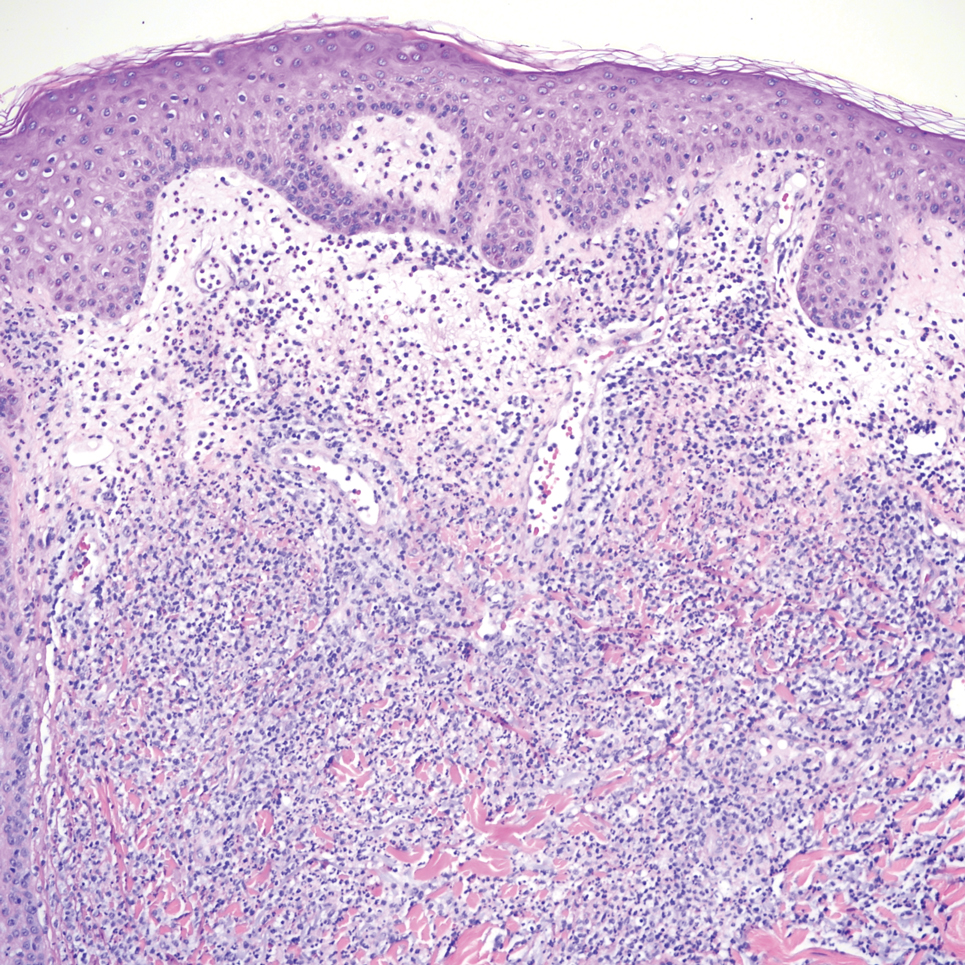

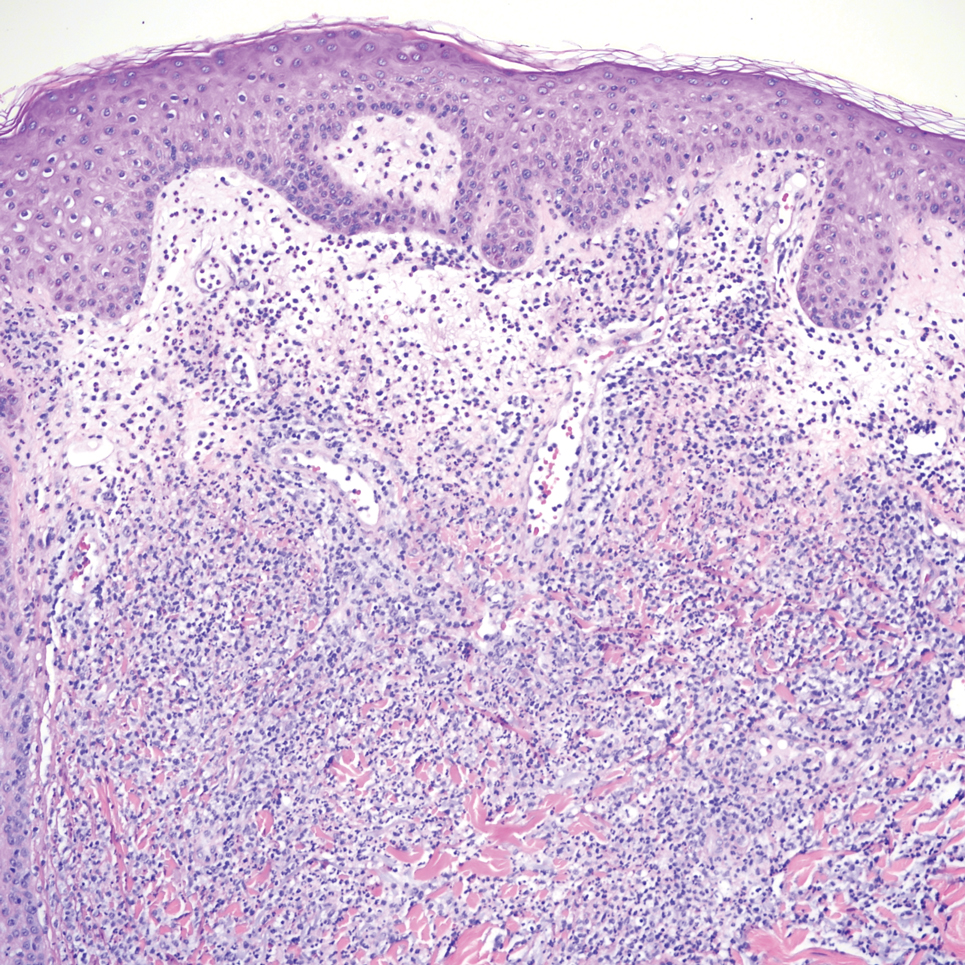

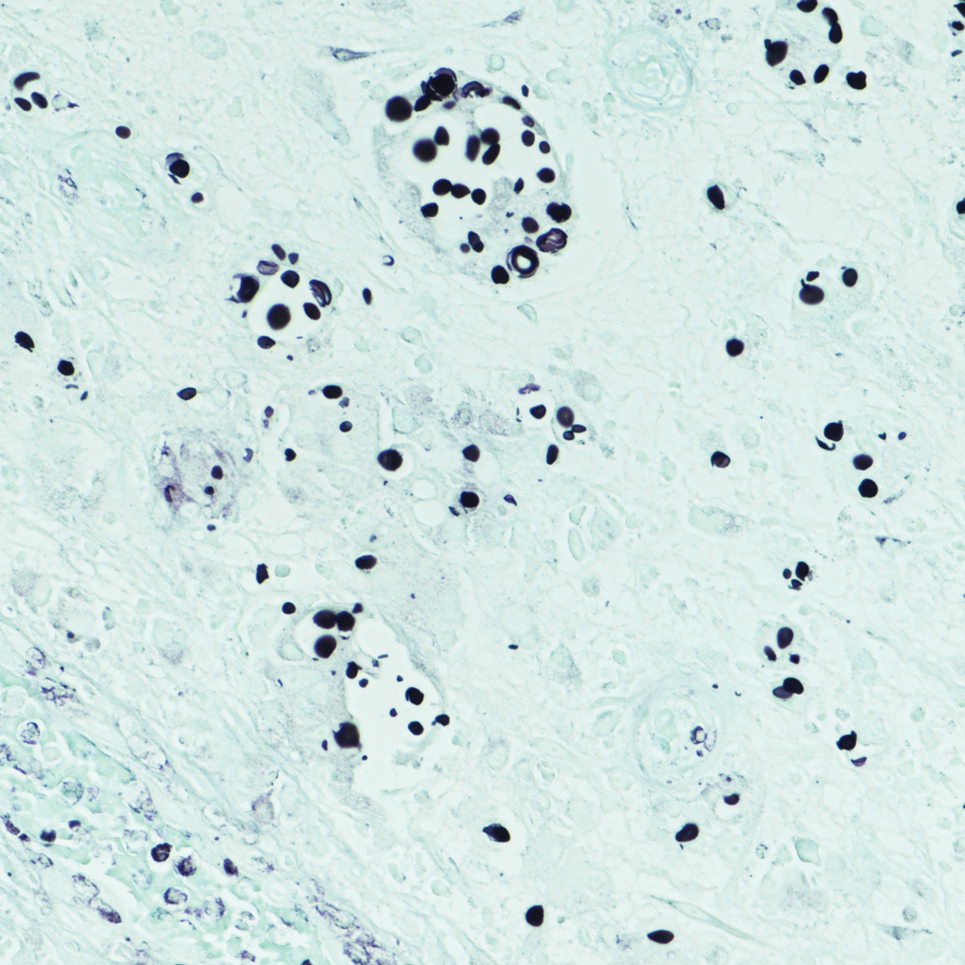

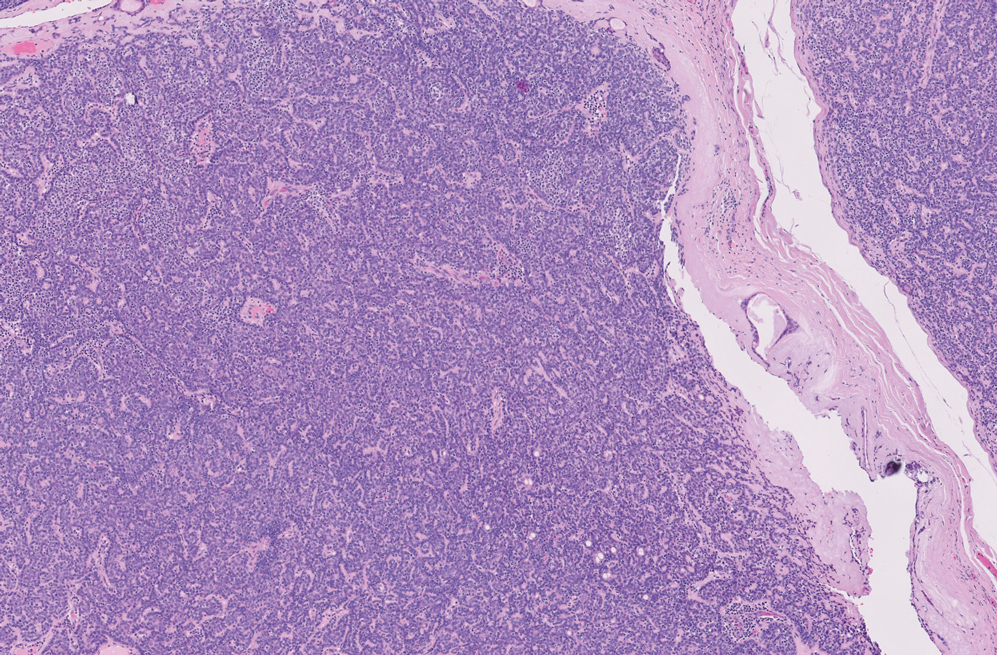

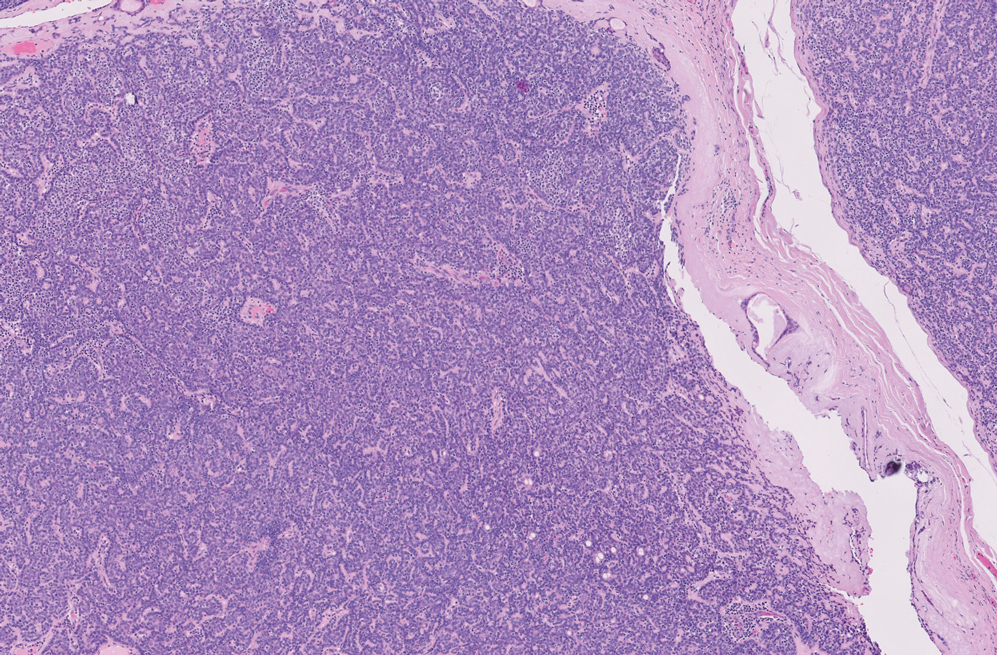

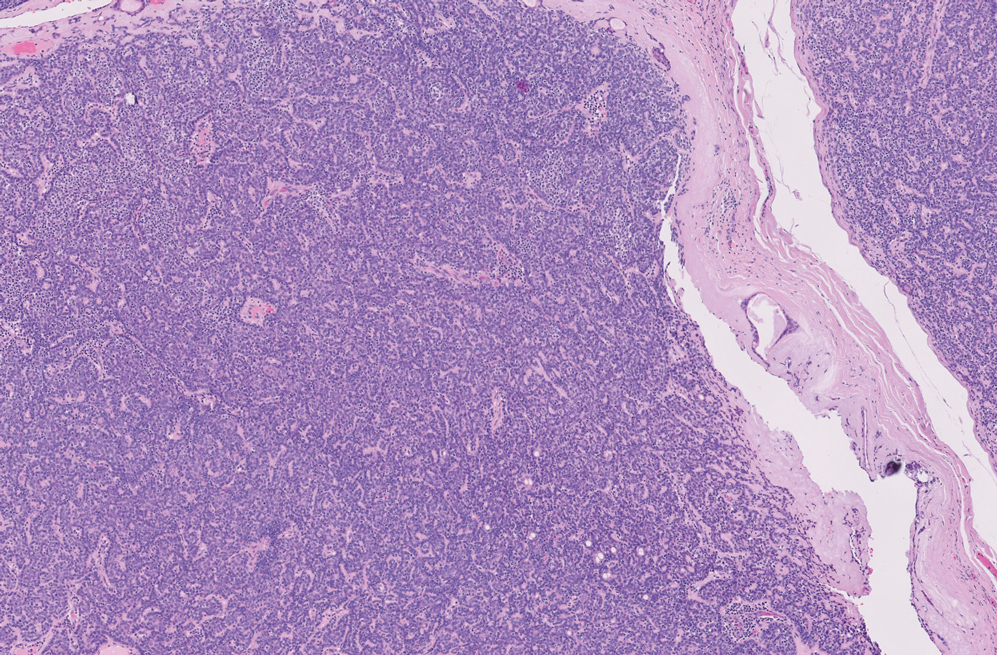

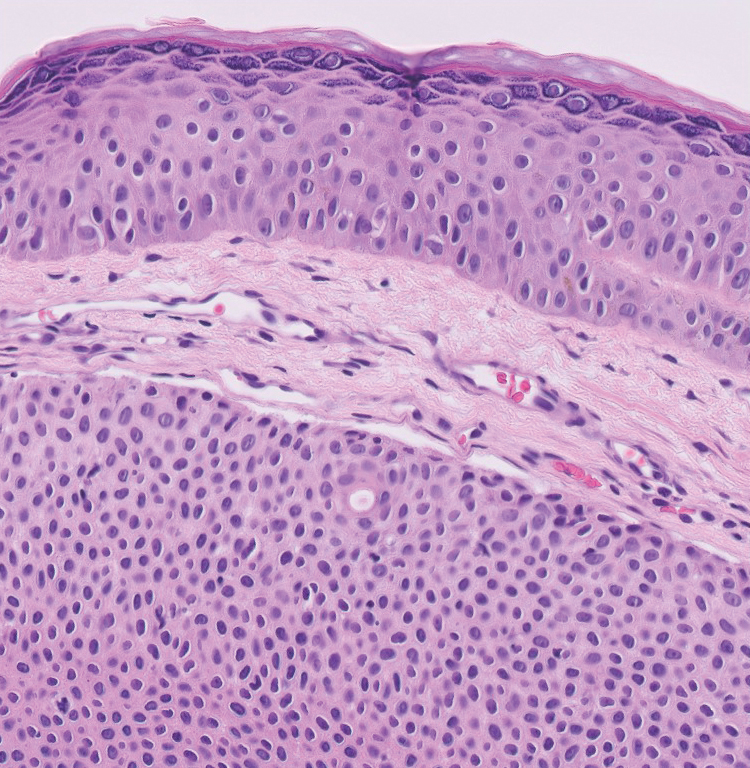

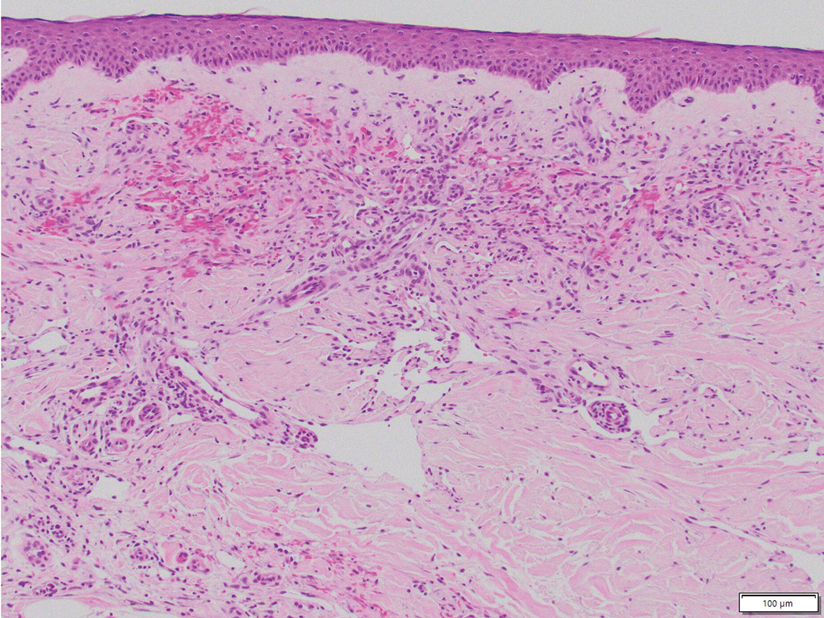

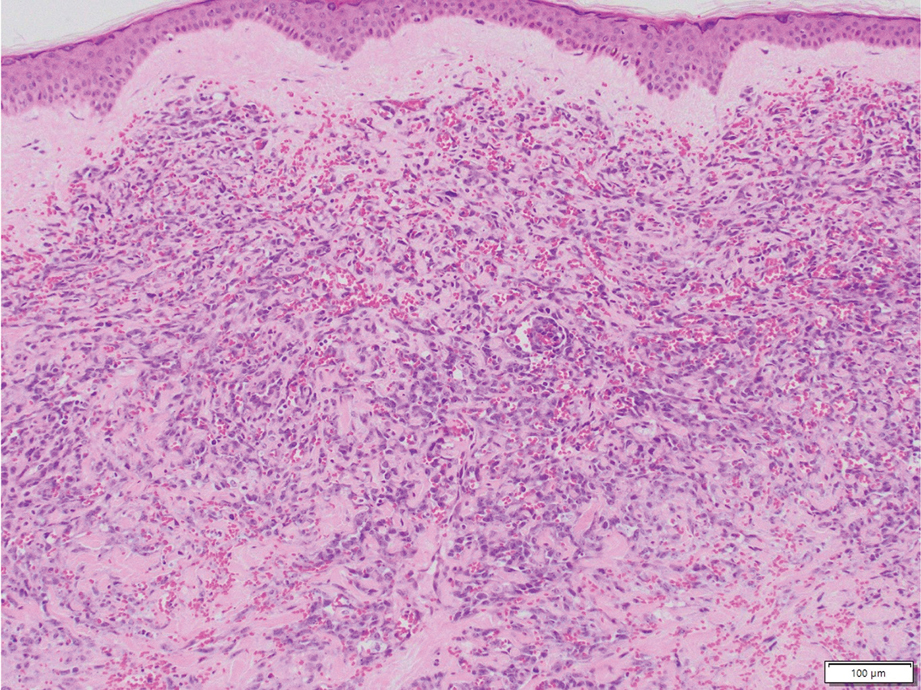

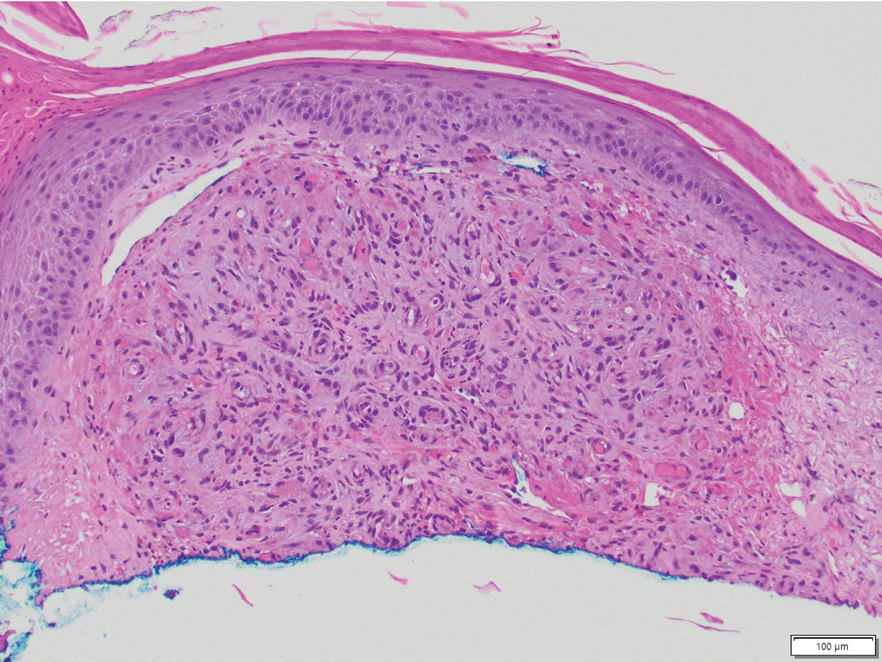

Lepromatous leprosy transmission is not fully understood but is thought to occur via airborne droplets from coughing/sneezing and nasal secretions.2 Histopathology generally shows a dense and diffuse granulomatous infiltrate that involves the dermis but is separated from the epidermis by a zone of collagen (grenz zone).3 Histology is characterized by the presence of lymphocytes and numerous foamy macrophages (lepra or Virchow cells) containing M leprae organisms. In persistent lesions, the high density of uncleared bacilli forms spherical cytoplasmic clumps known as globi within enlarged foamy histiocytes (Figure 1).4 The macrophages form granulomatous lesions in the skin and around nerve bundles, resulting in tissue damage and decreased sensation. The current standard of care for LL is a multidrug combination of dapsone, rifampin, and clofazimine. Early diagnosis and complete treatment of LL is crucial, as this approach typically leads to complete cure of the disease.

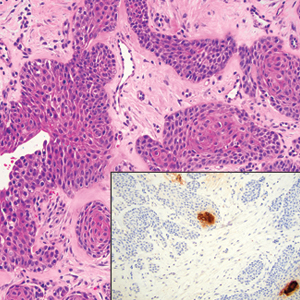

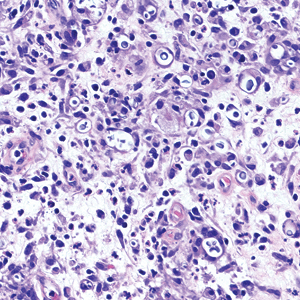

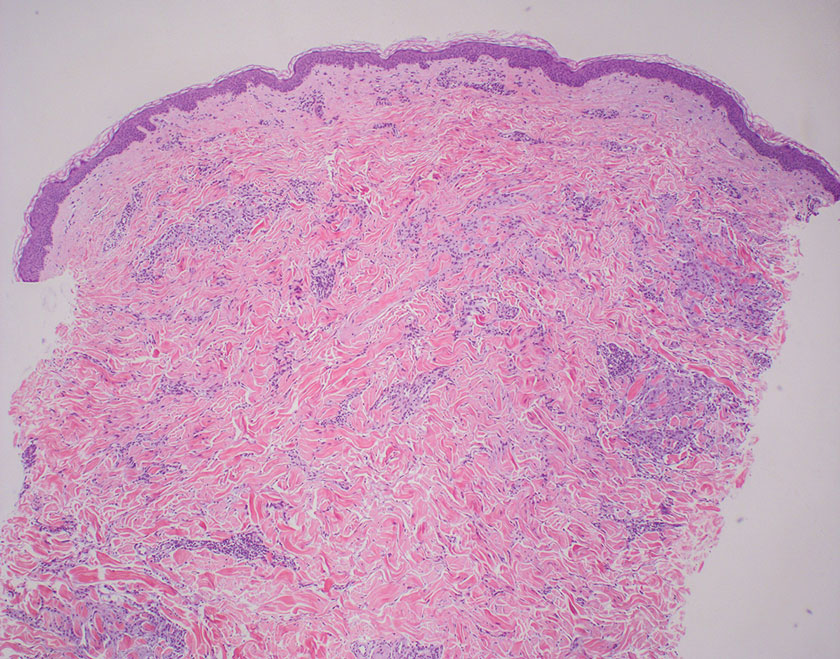

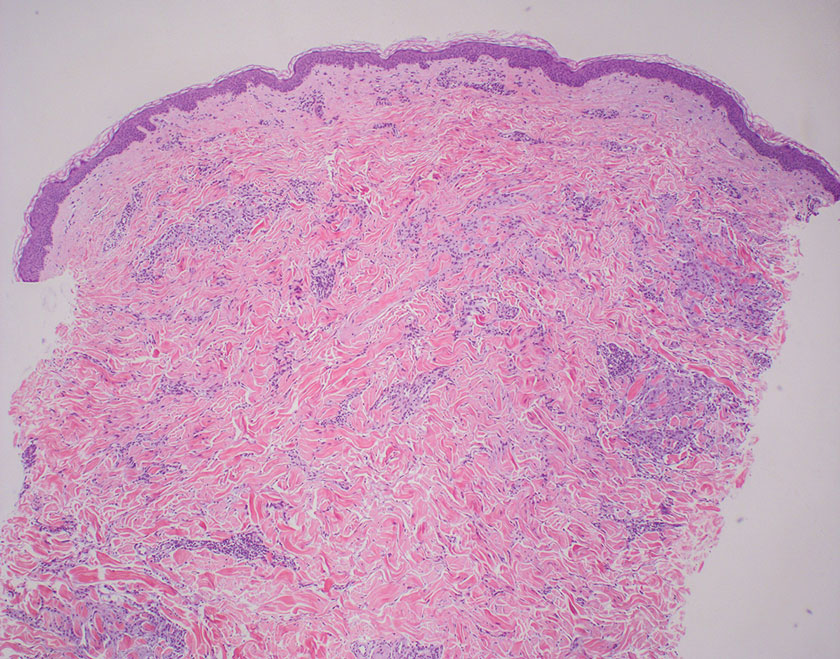

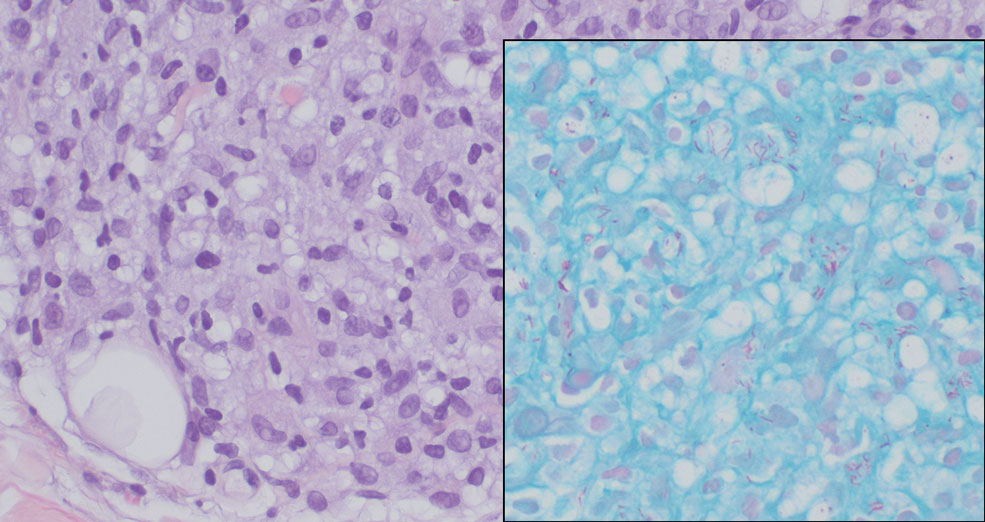

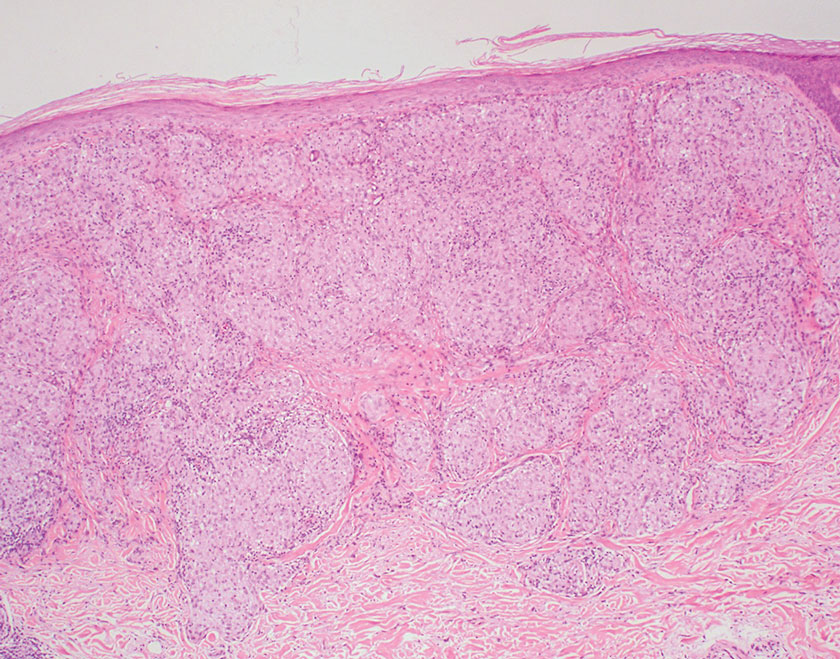

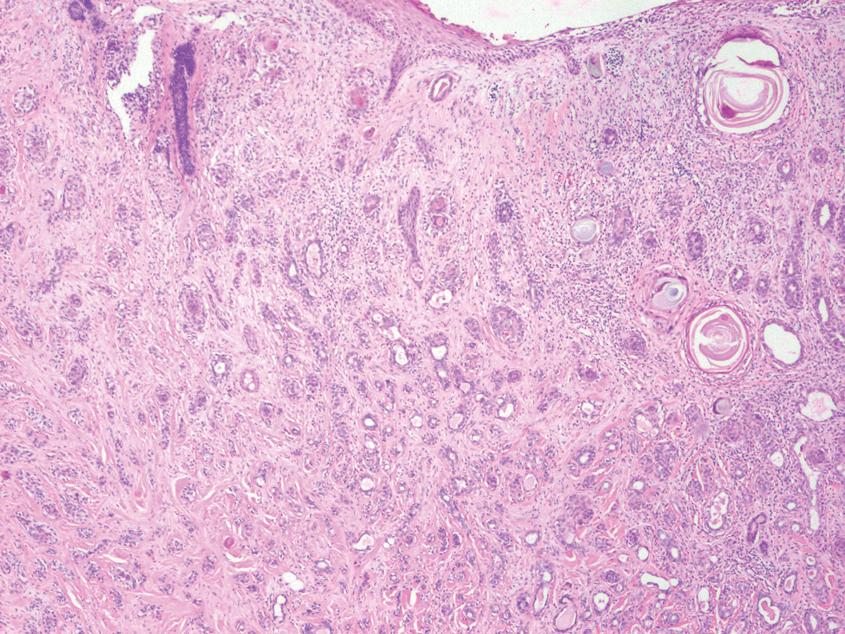

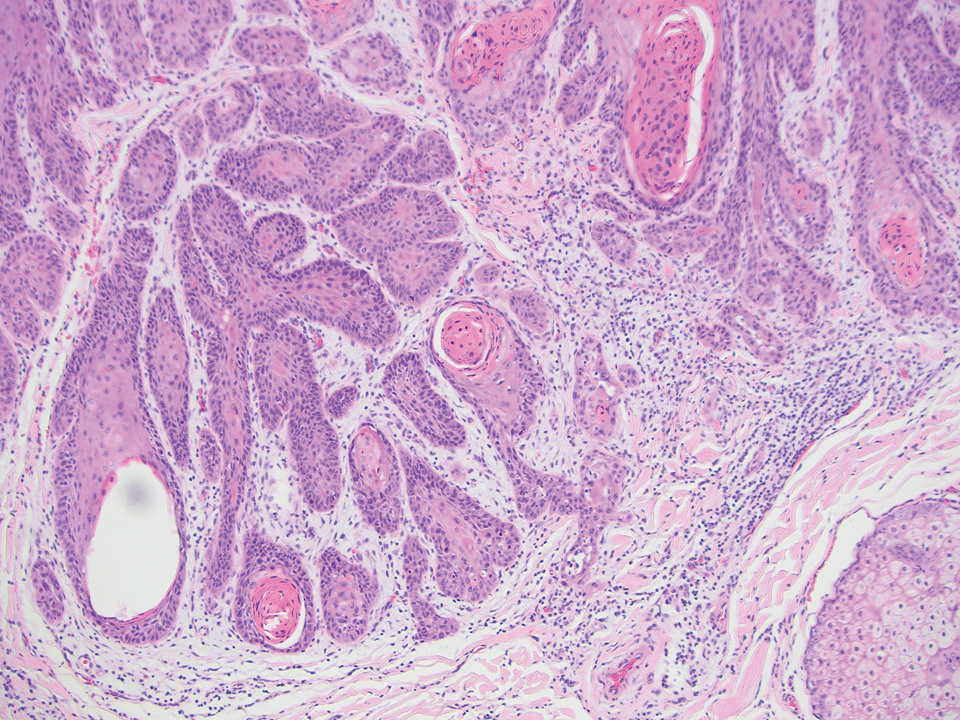

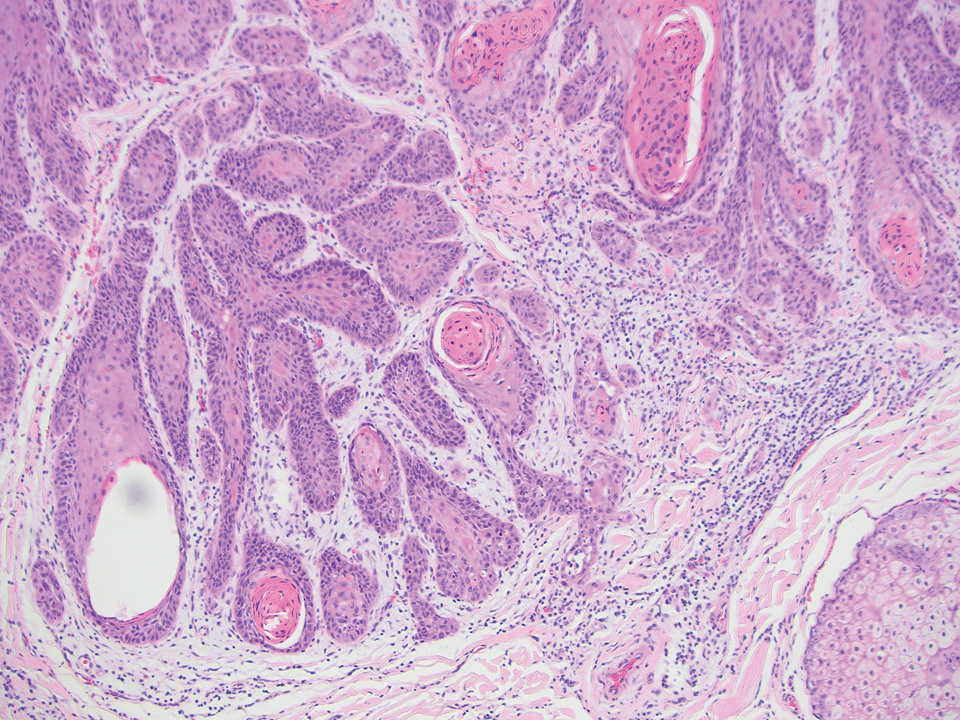

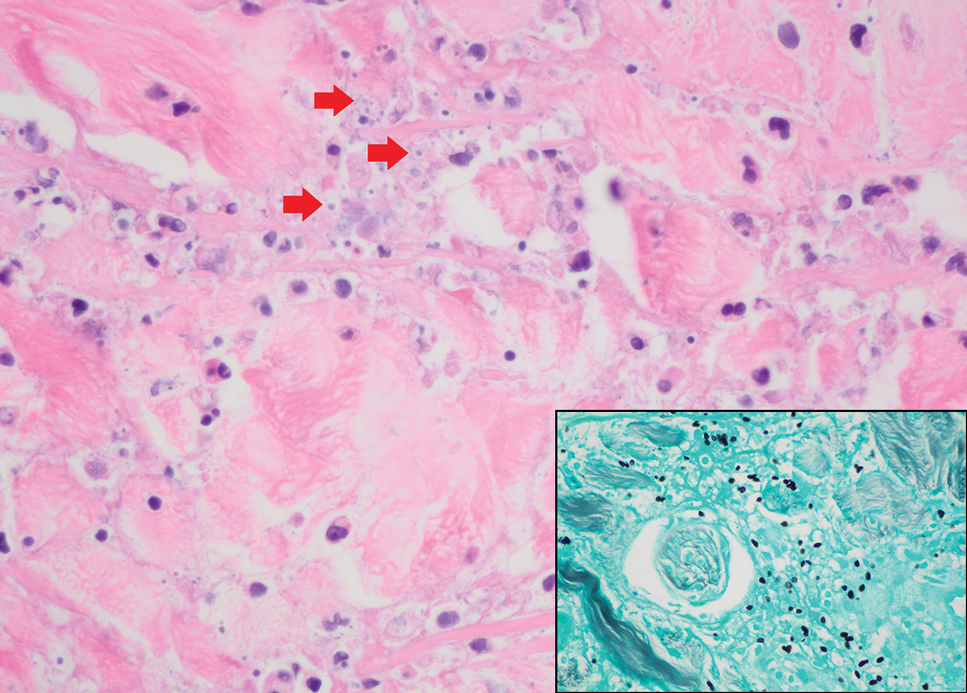

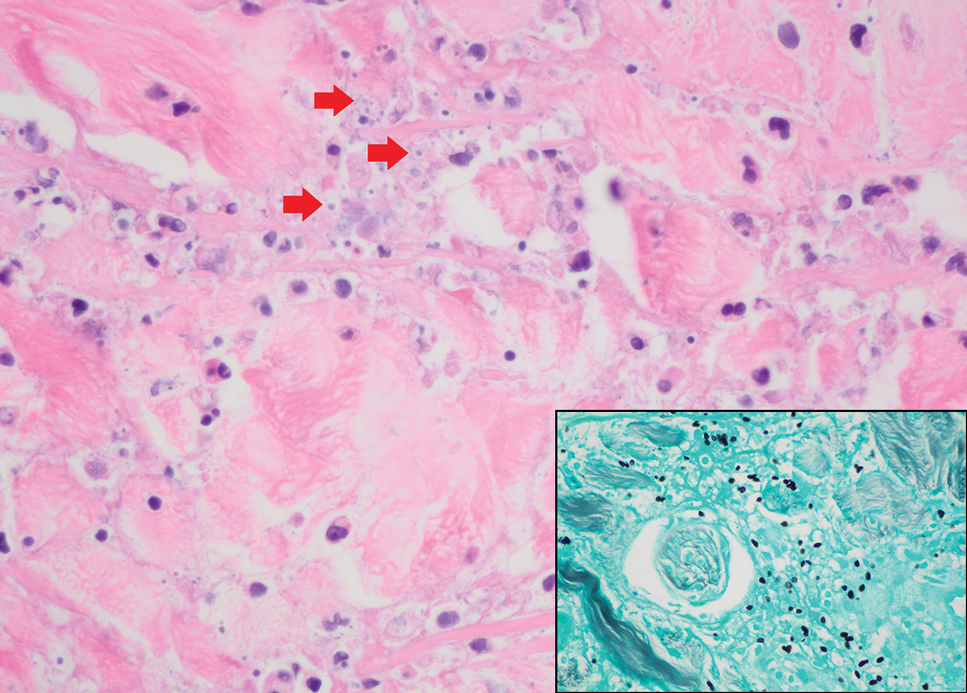

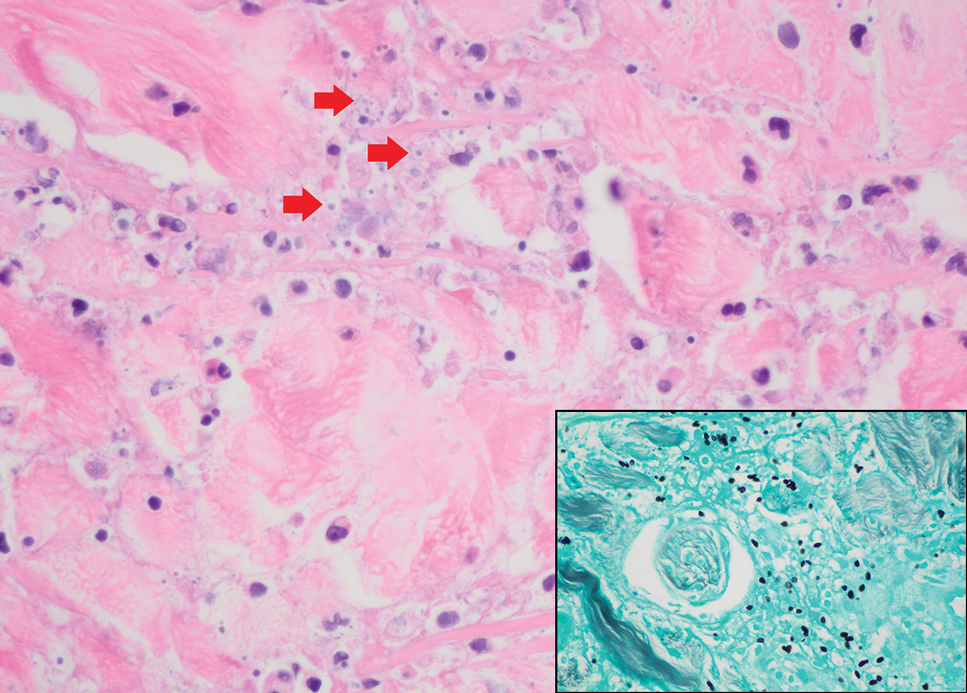

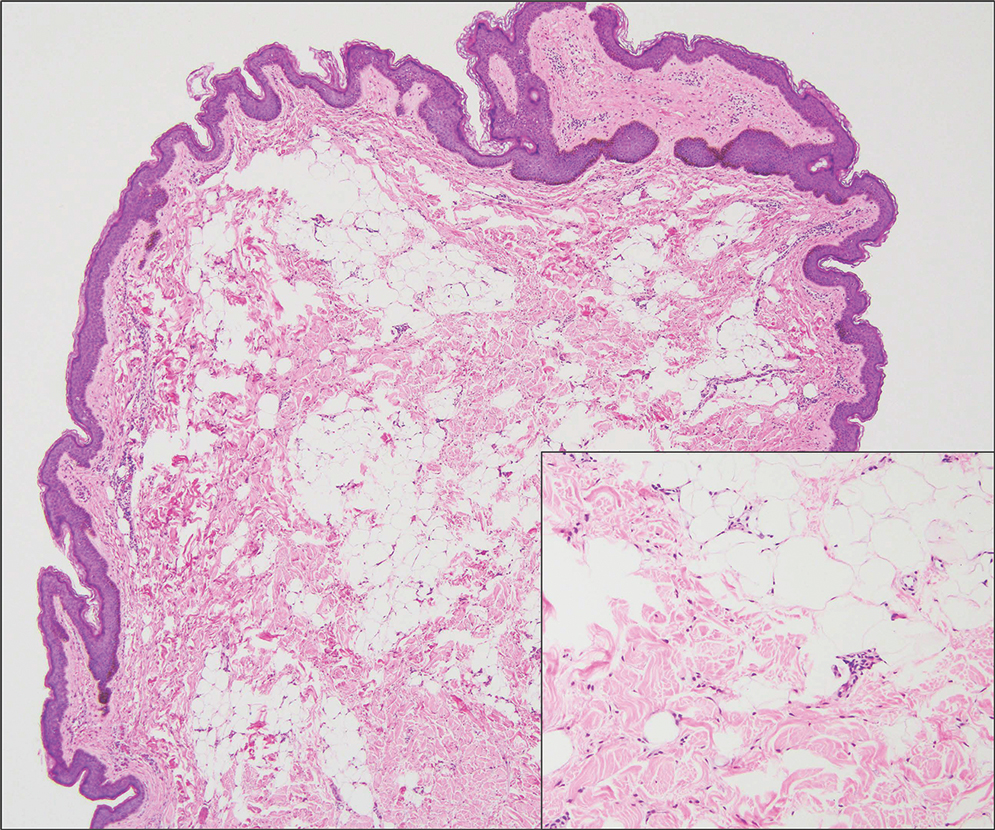

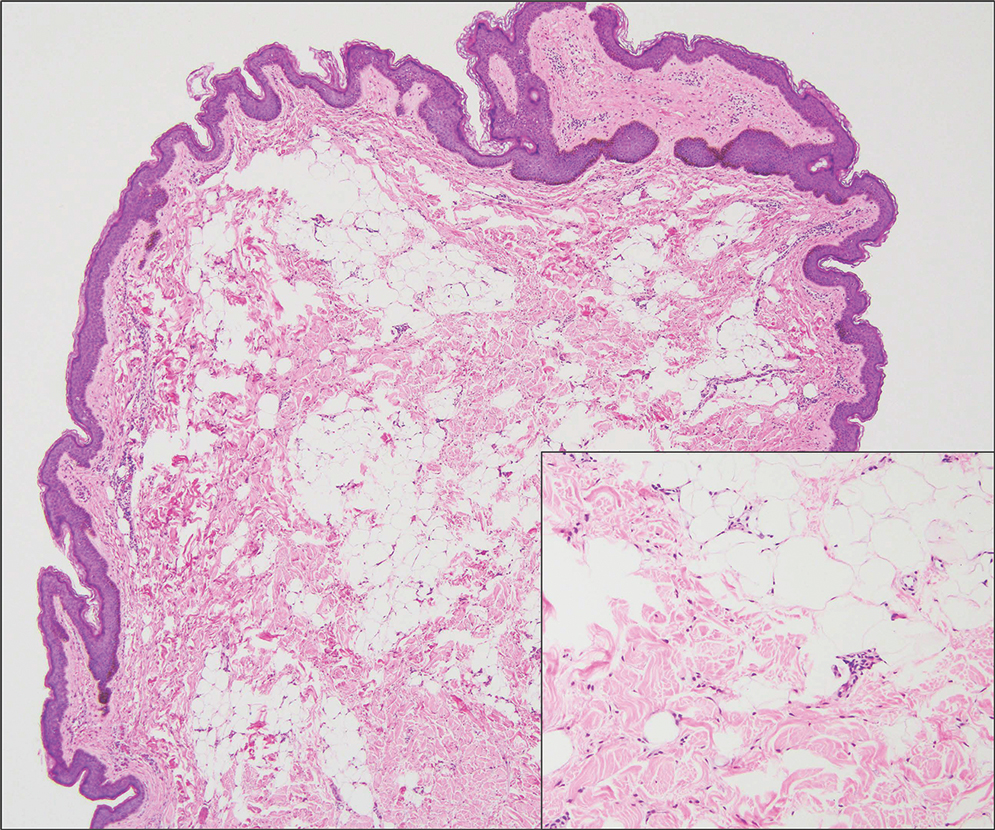

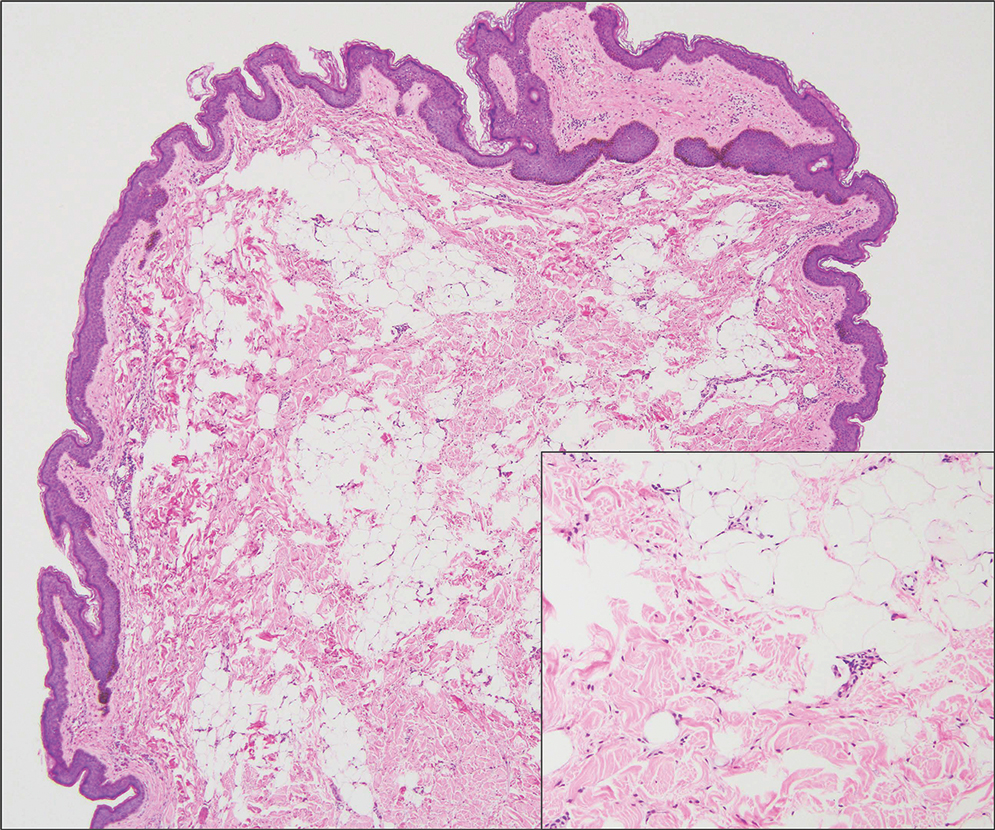

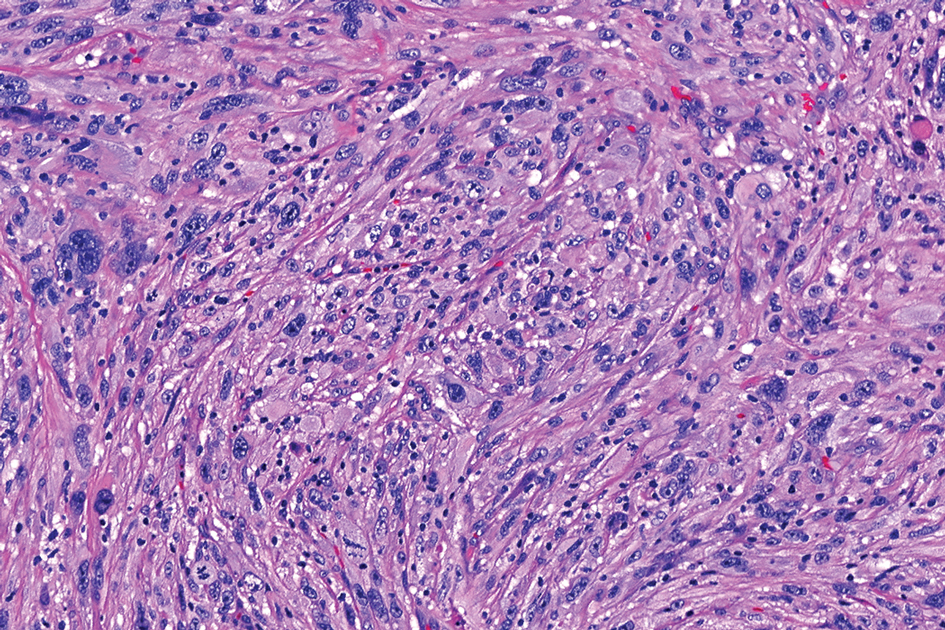

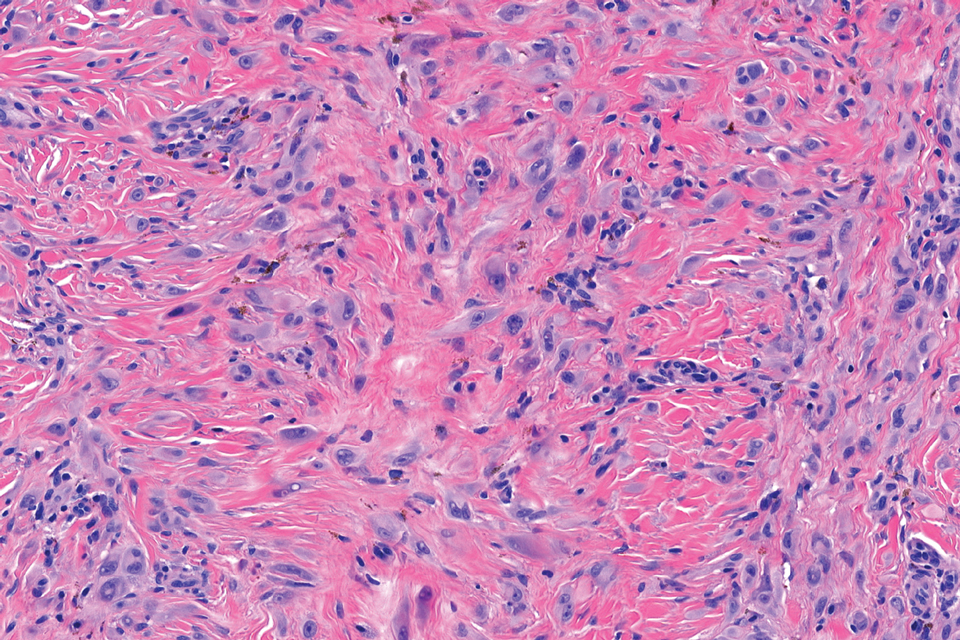

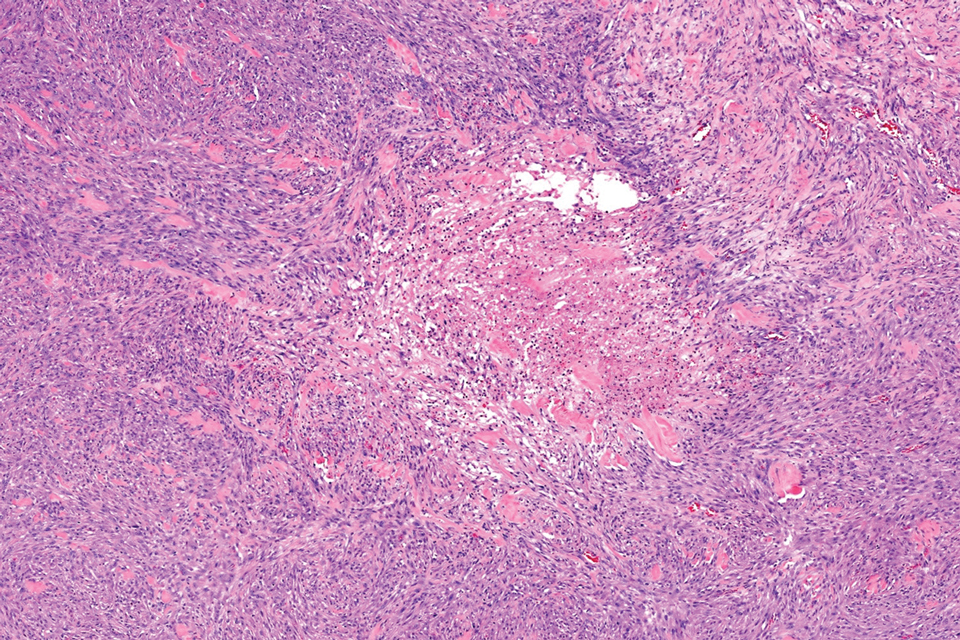

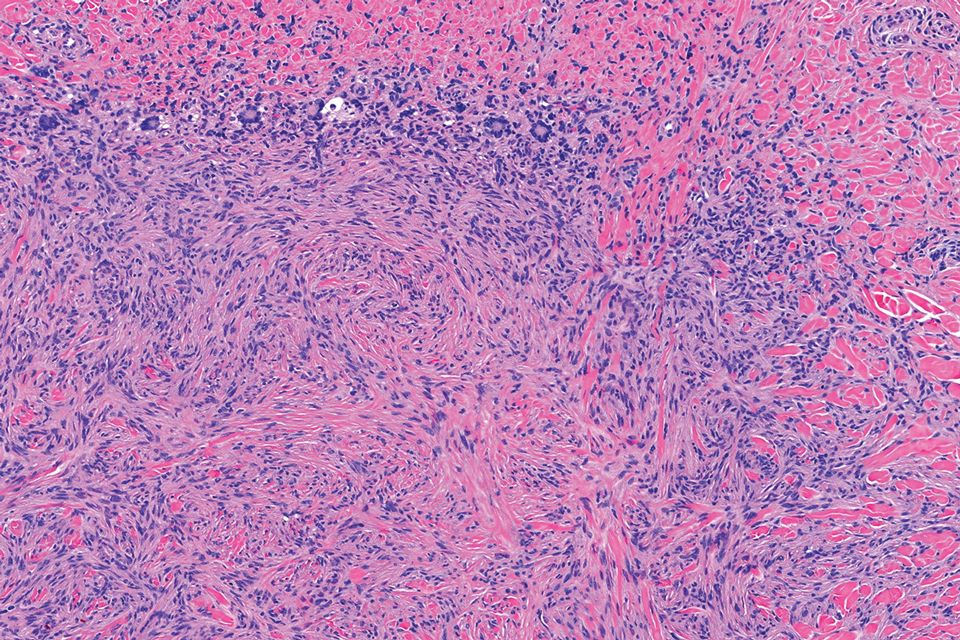

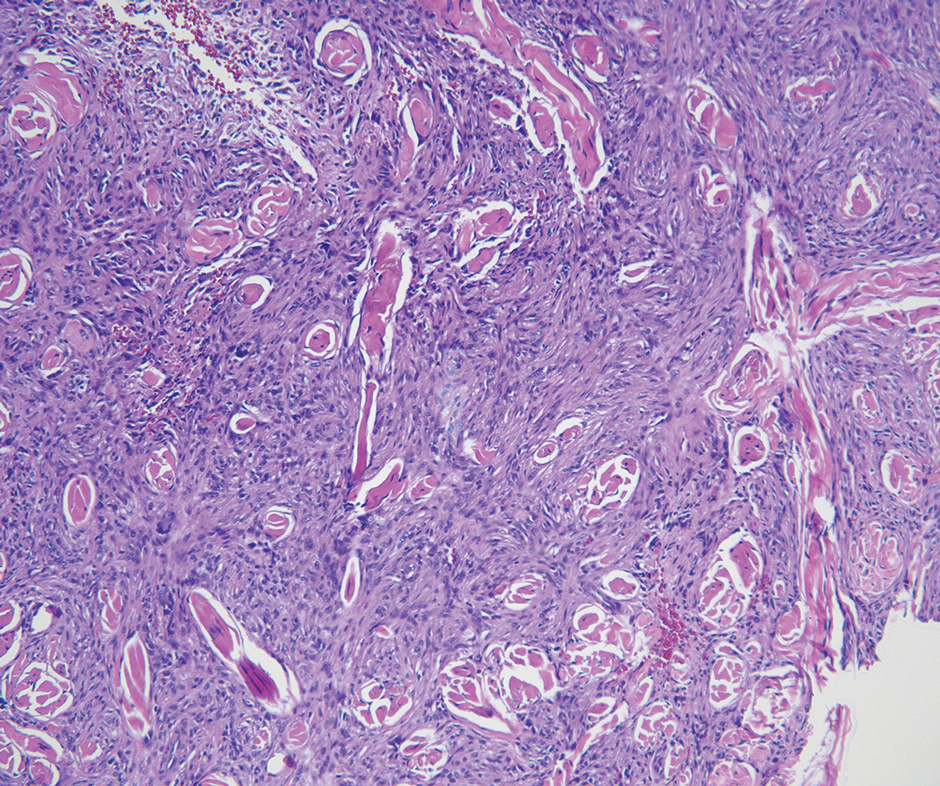

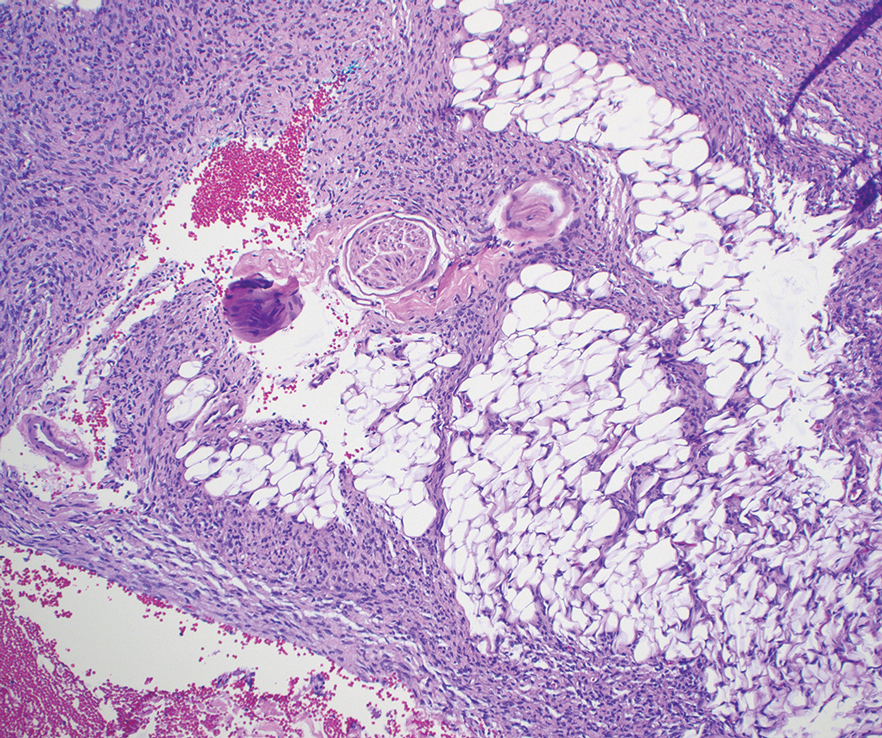

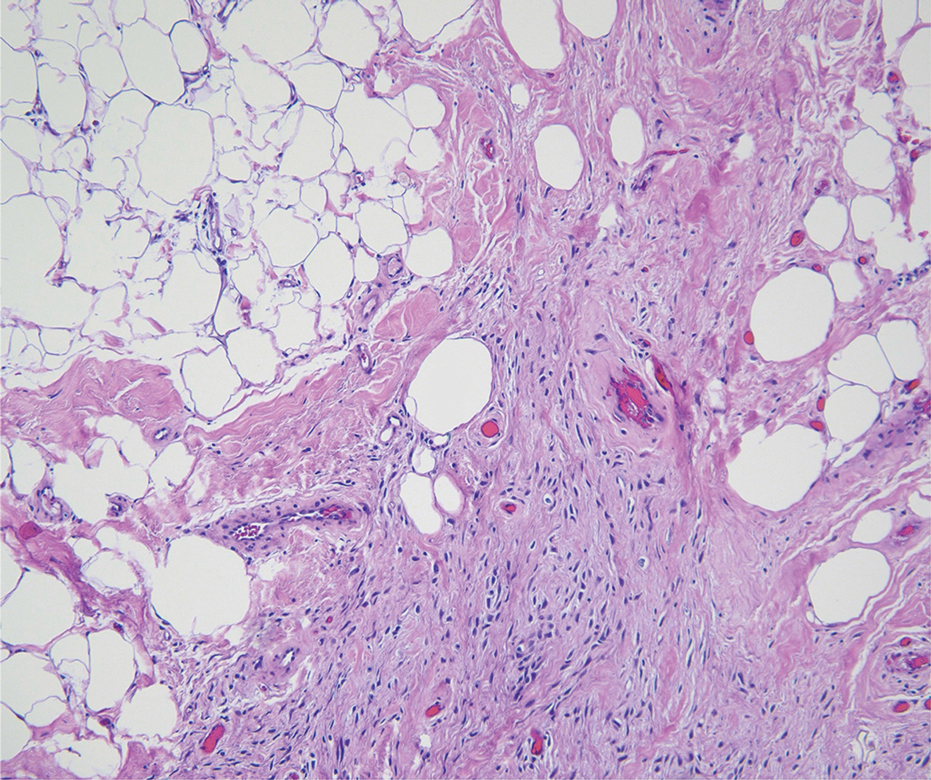

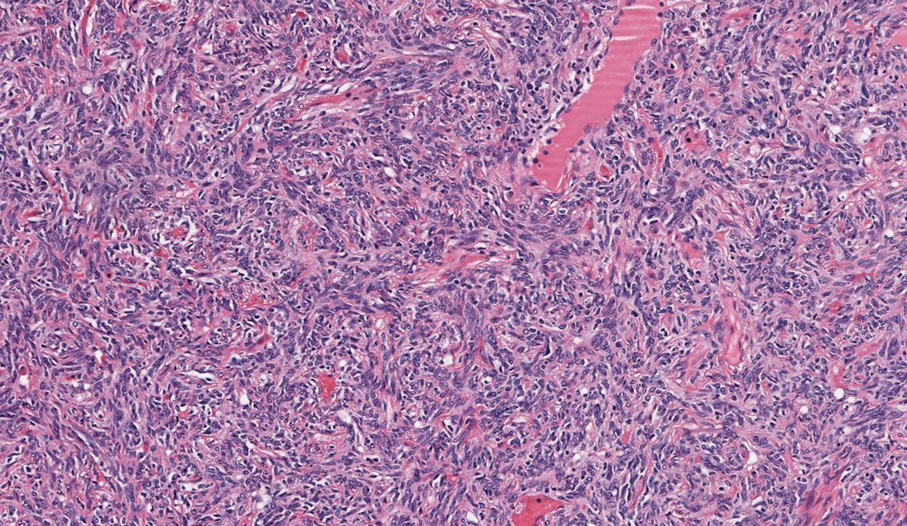

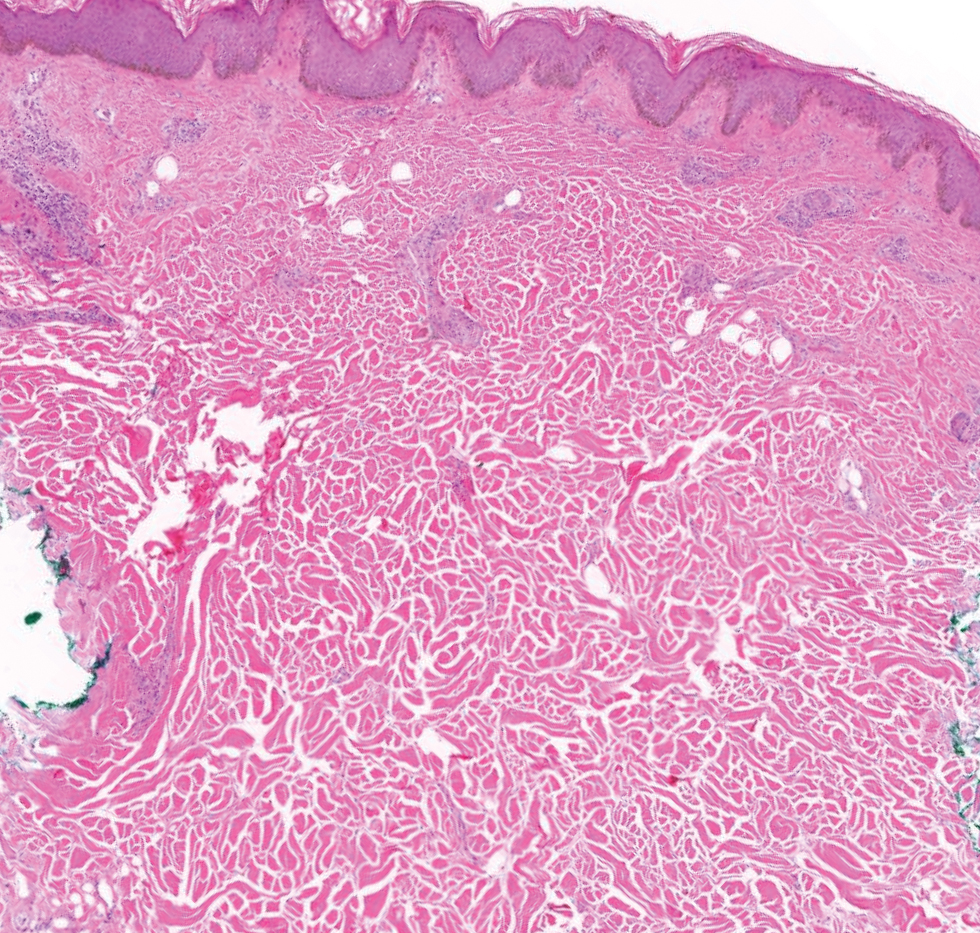

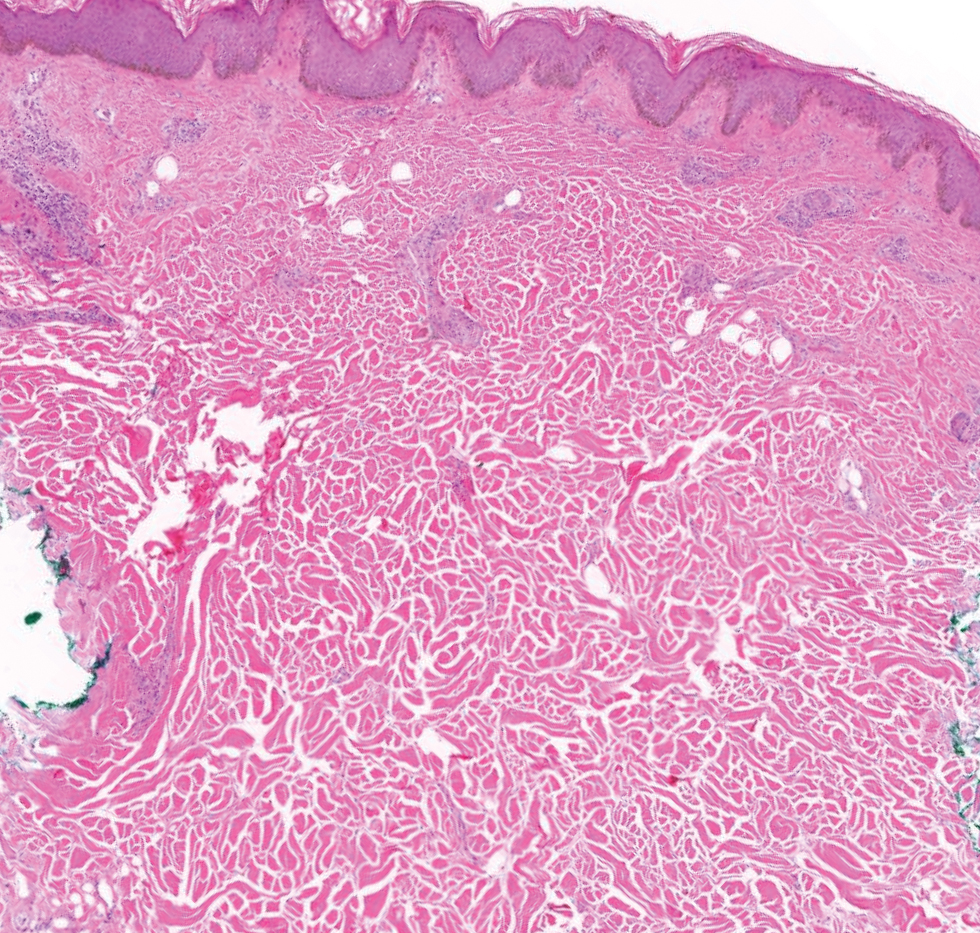

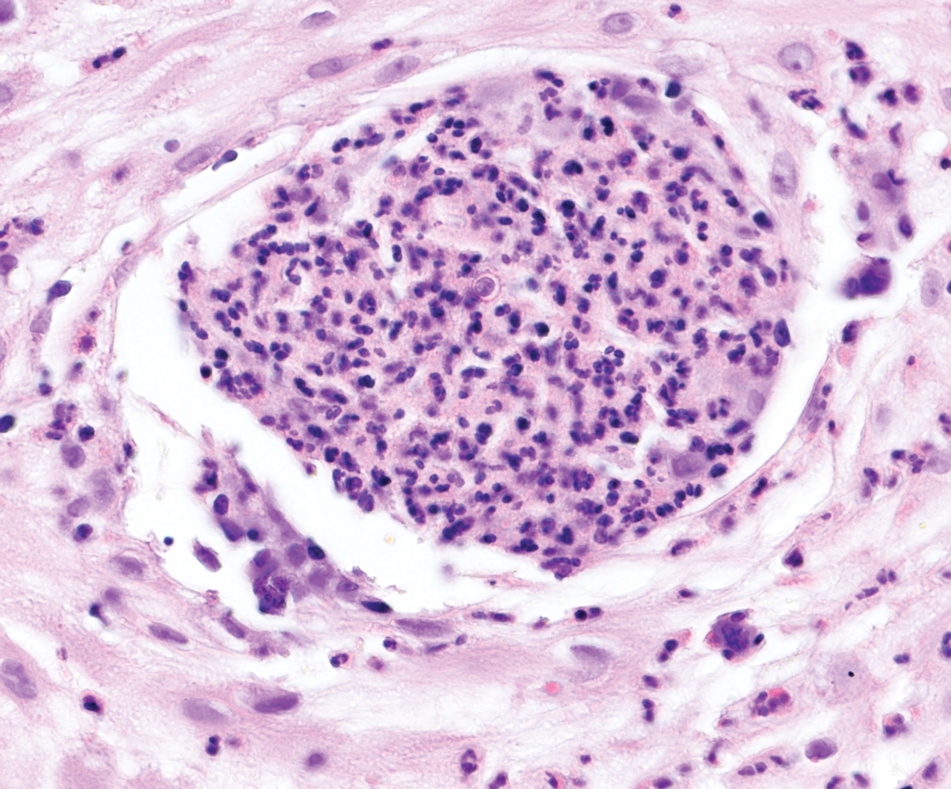

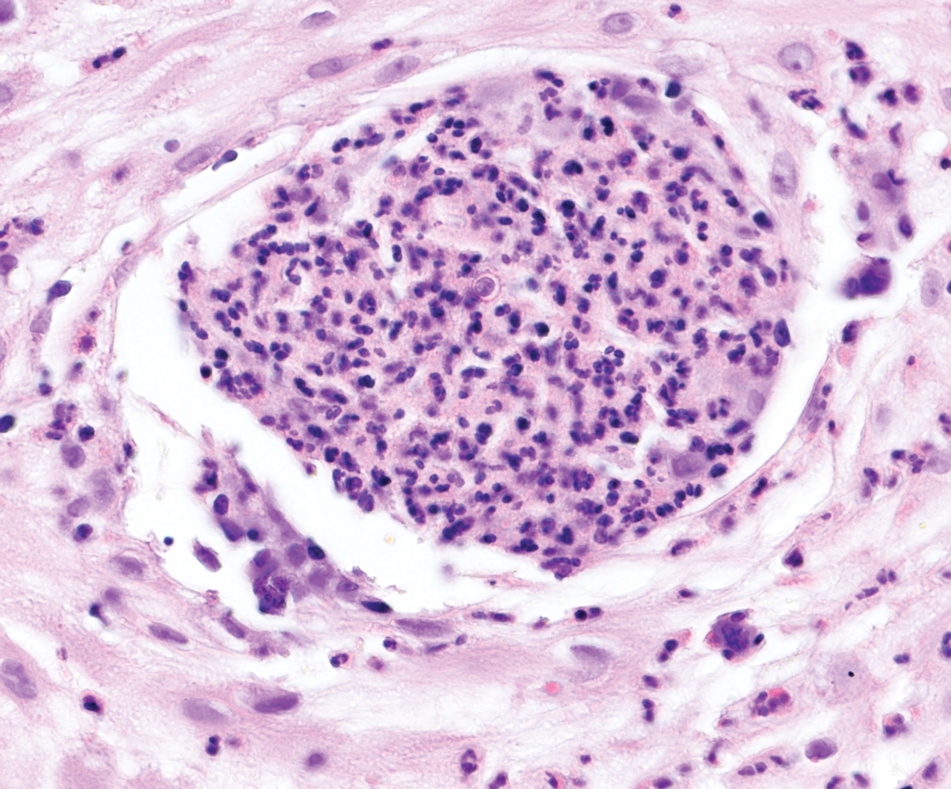

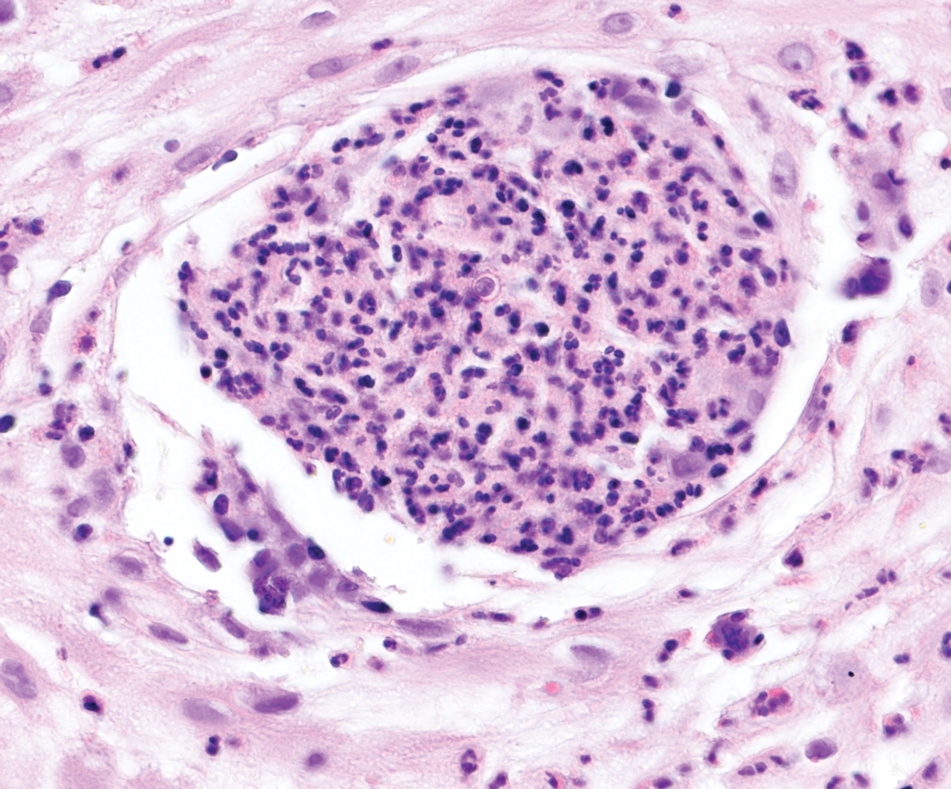

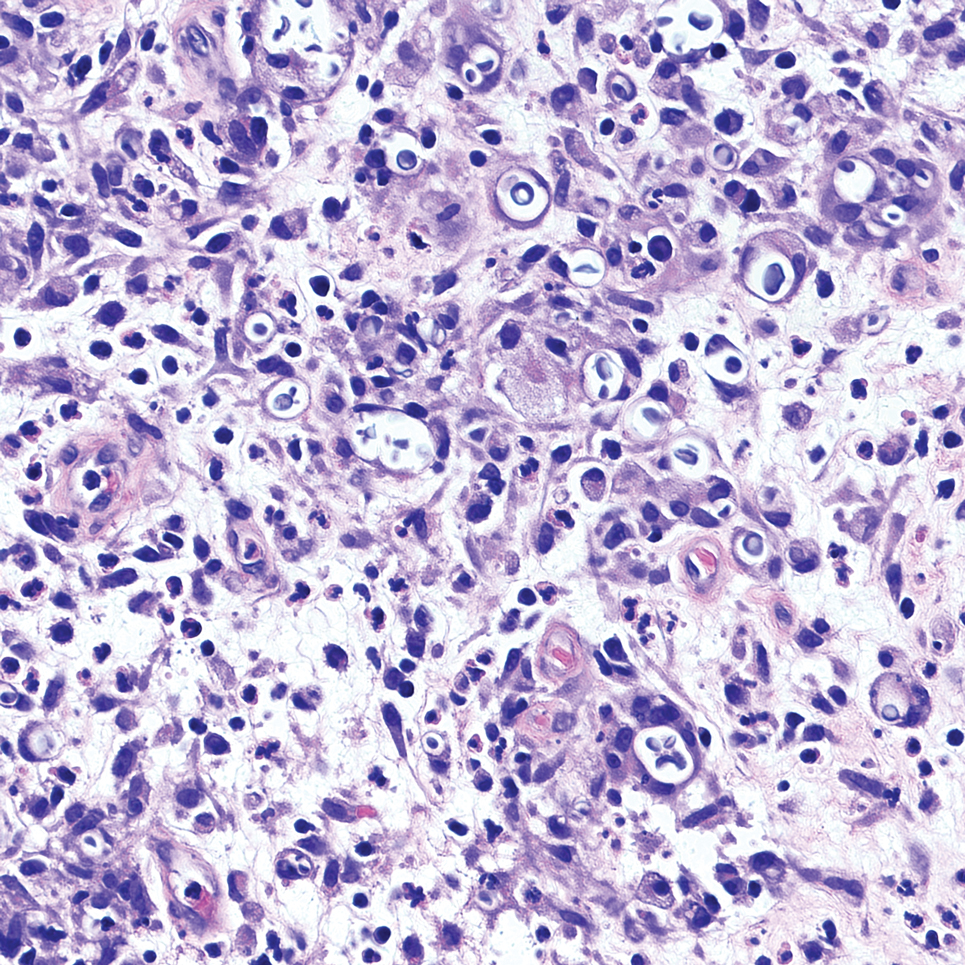

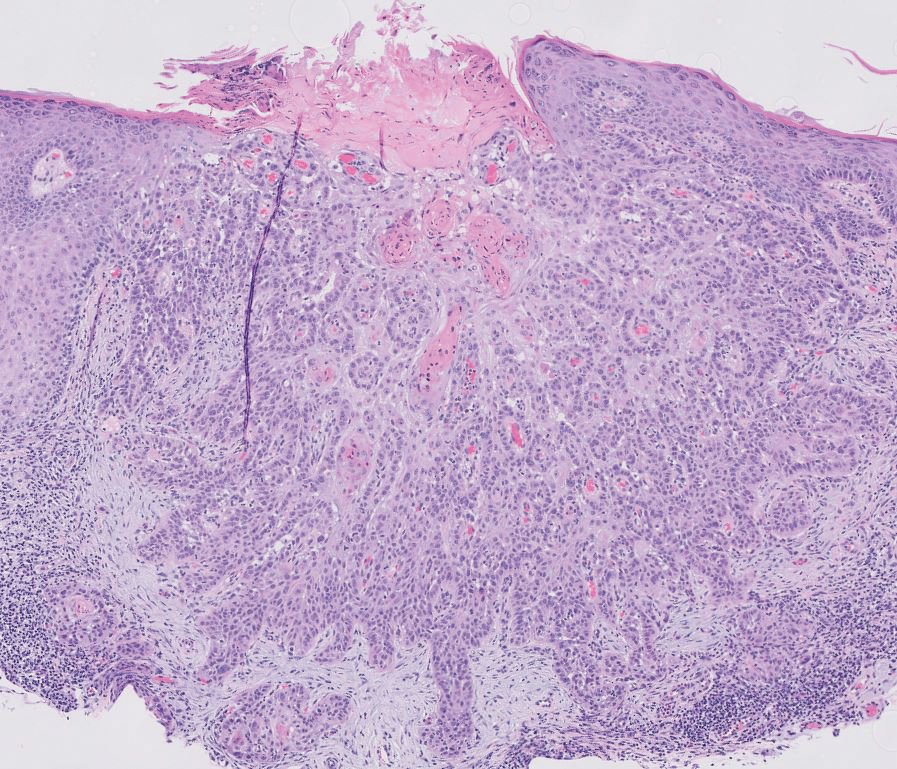

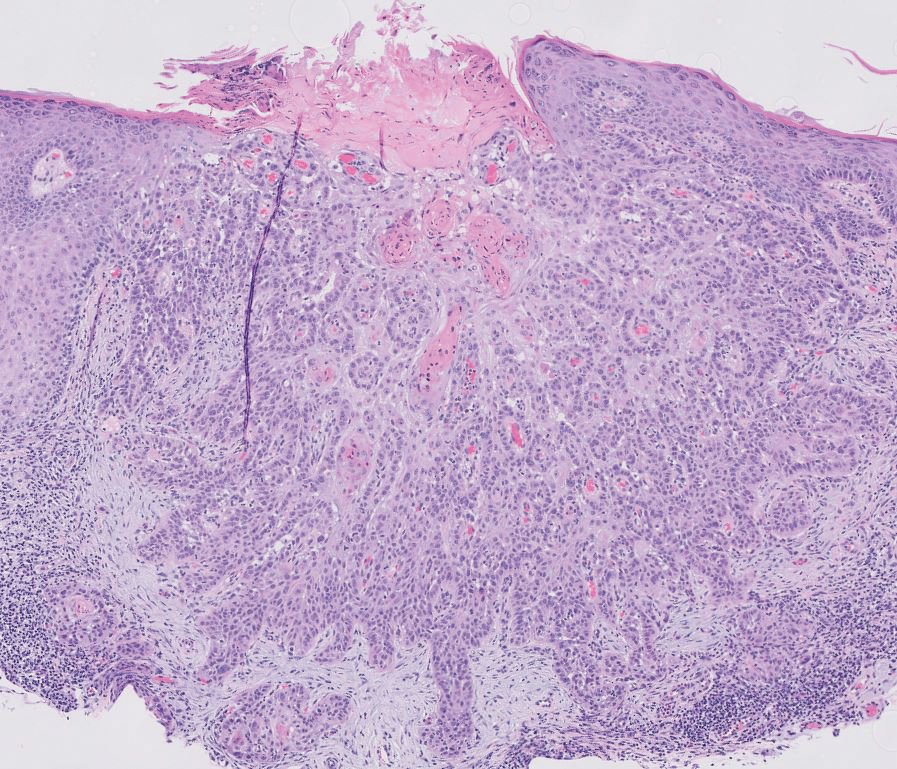

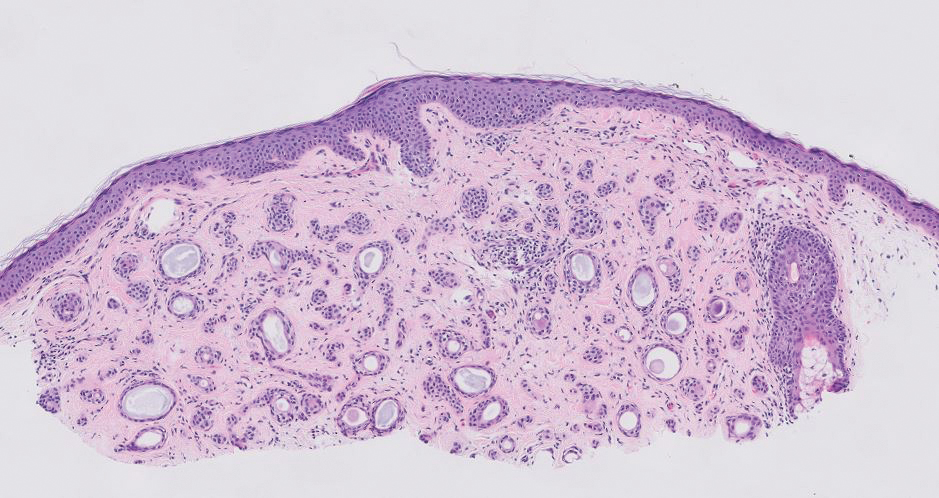

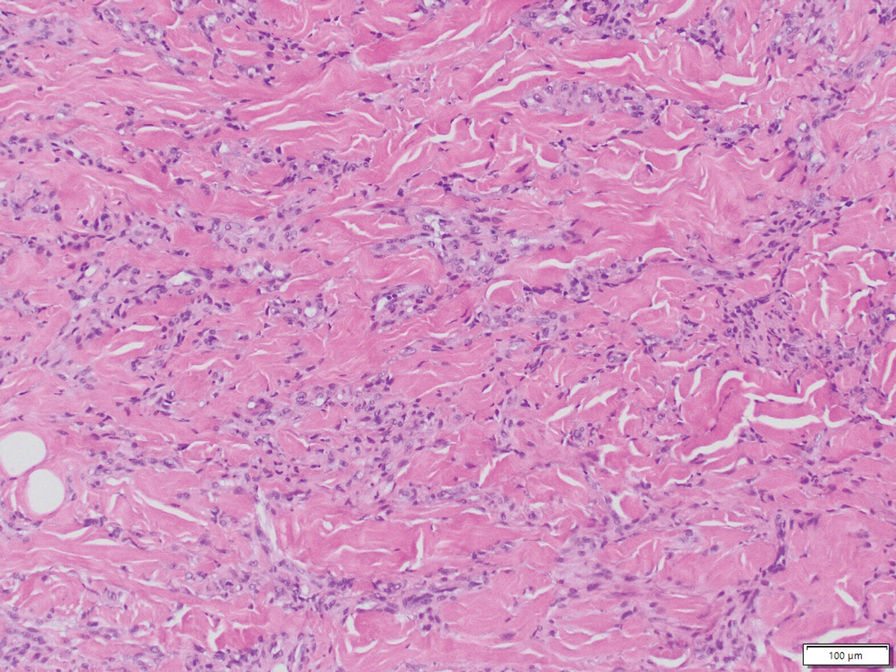

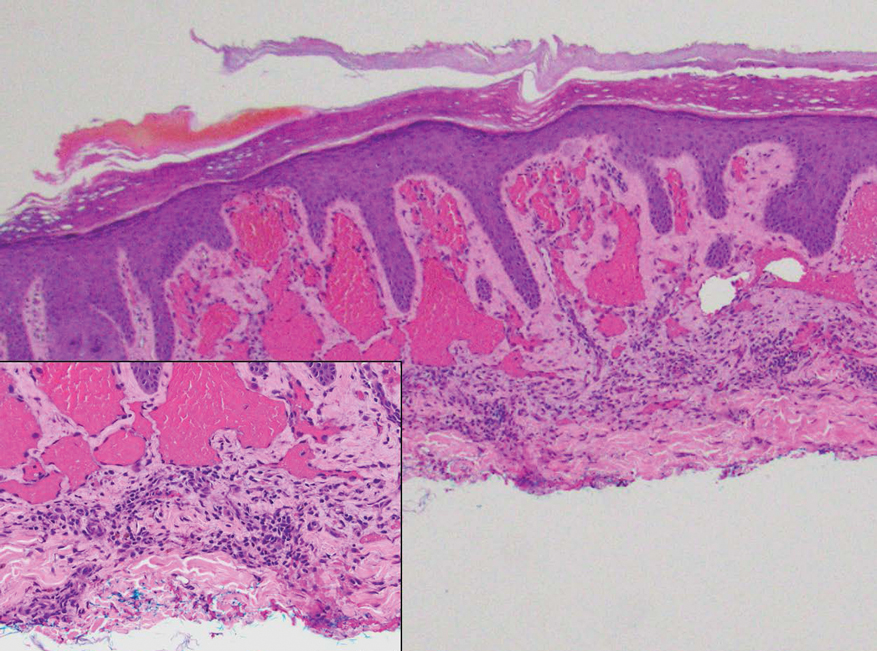

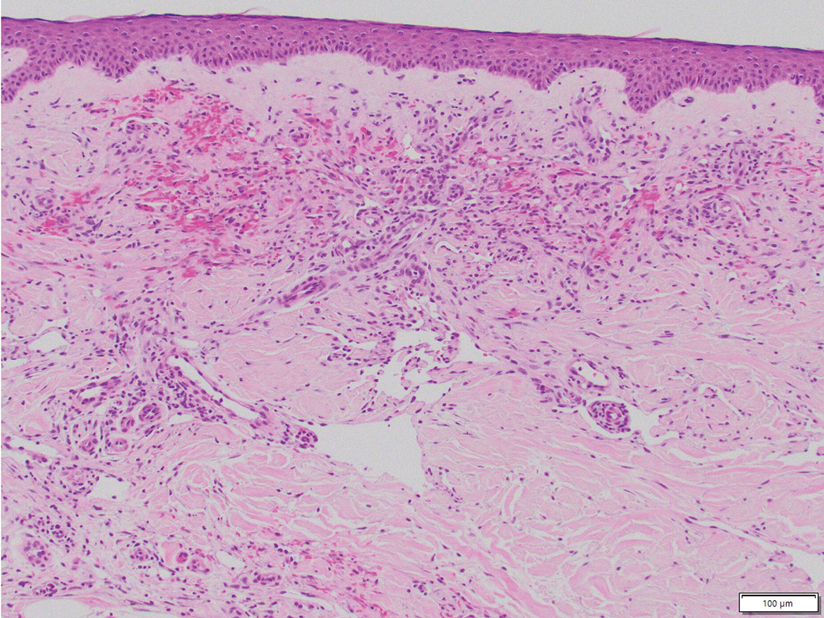

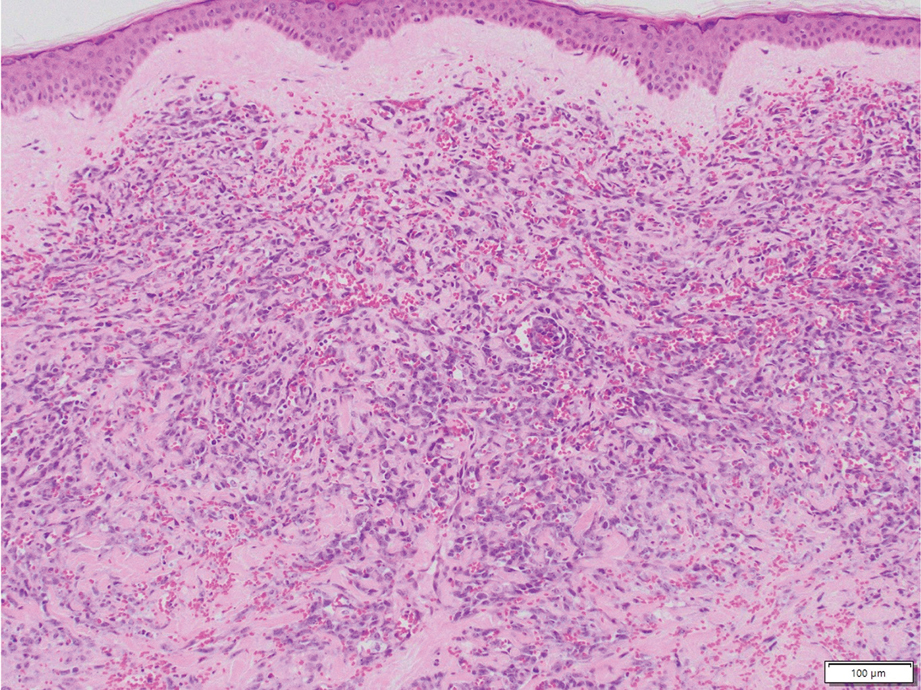

The differential diagnosis for LL includes granuloma annulare (GA), mycosis fungoides (MF), sarcoidosis, and subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE). Granuloma annulare is a noninfectious inflammatory granulomatous skin disease that manifests in a localized, generalized, or subcutaneous pattern. Localized GA is the most common form and manifests as self-resolving, flesh-colored or erythematous papules or plaques limited to the extremities.5,6 Generalized GA is defined by more than 10 widespread annular plaques involving the trunk and extremities and can persist for decades.6 This form can be associated with hyperlipidemia, diabetes, autoimmune disease and immunodeficiency (eg, HIV), and rarely with lymphoma or solid tumors. On histology, GA shows necrobiosis surrounded by palisading histiocytes and mucin (palisading GA) or patchy interstitial histiocytes and lymphocytes (interstitial GA)(Figure 2).6 This palisading pattern differs from the histiocytes in LL, which contain numerous acid-fast bacilli and bacterial clumps. Topical and intralesional corticosteroids are first-line therapies for GA.

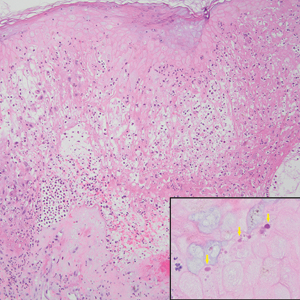

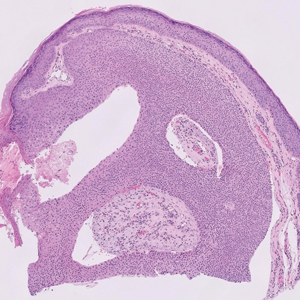

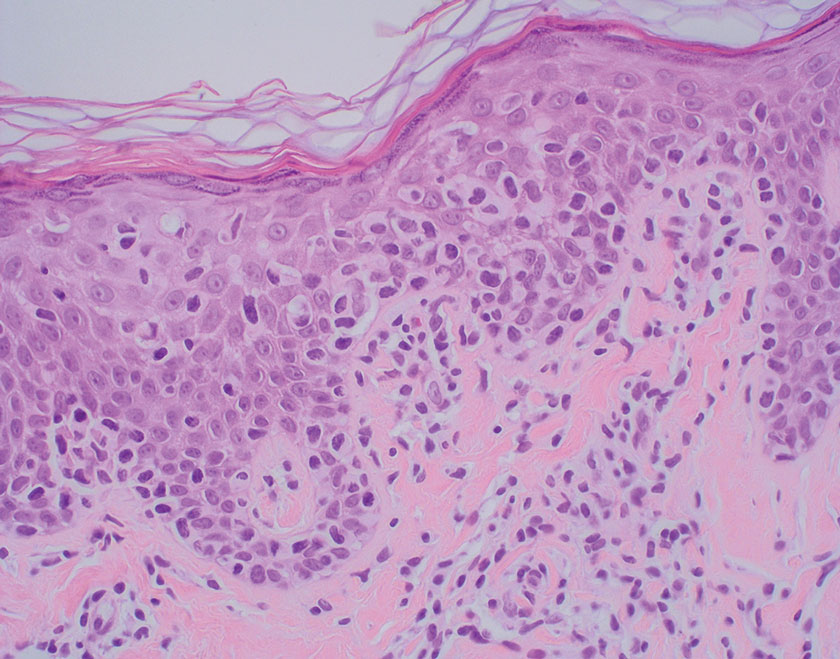

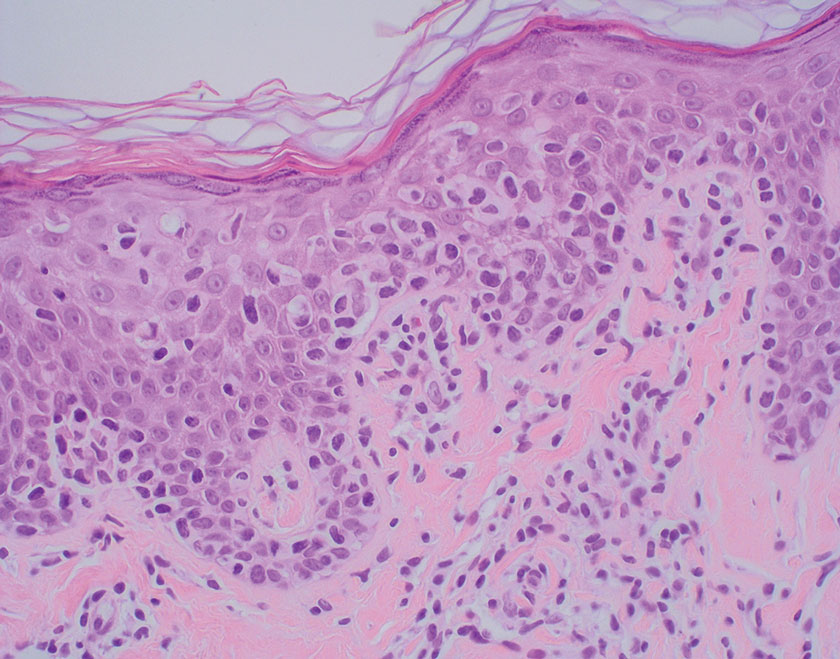

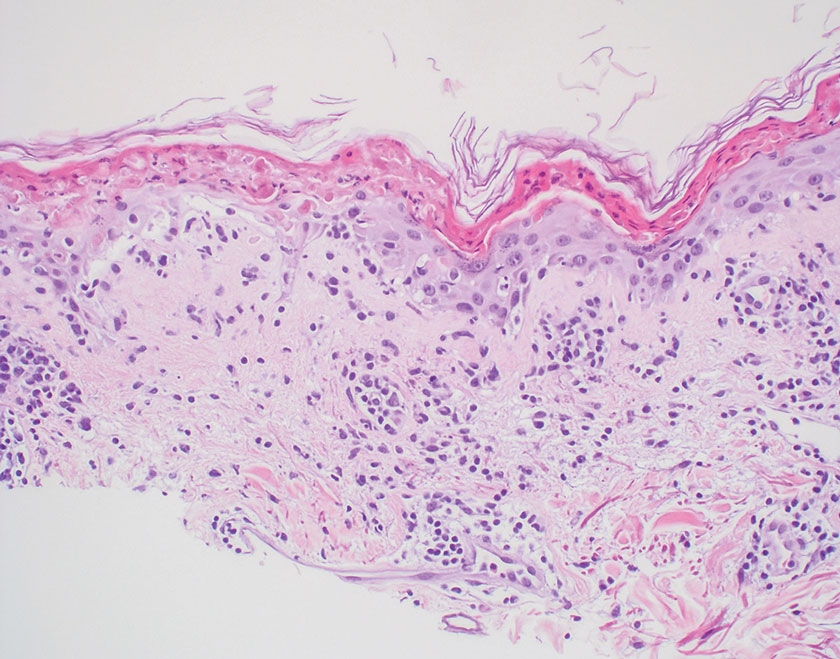

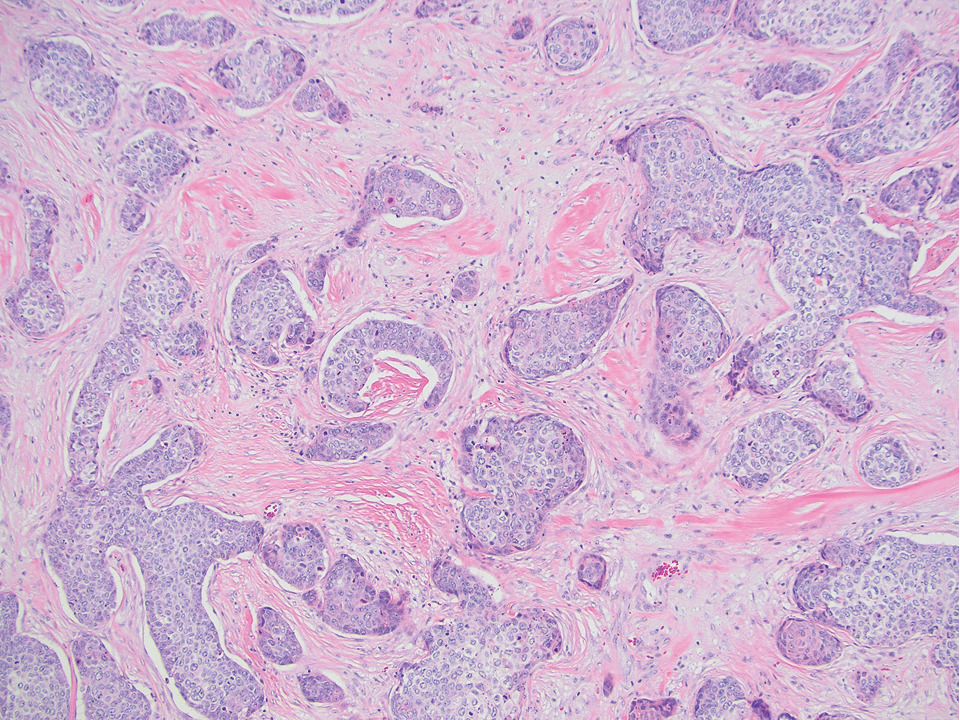

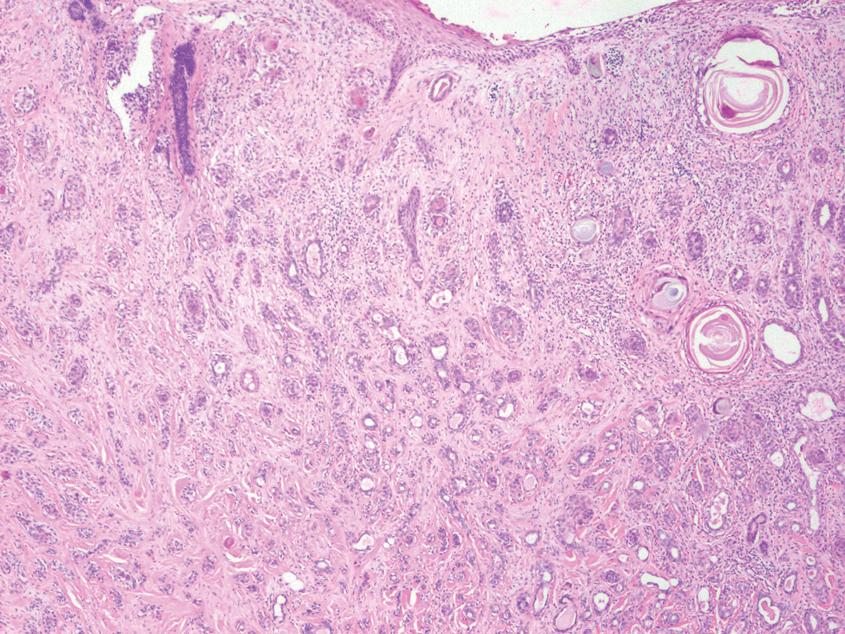

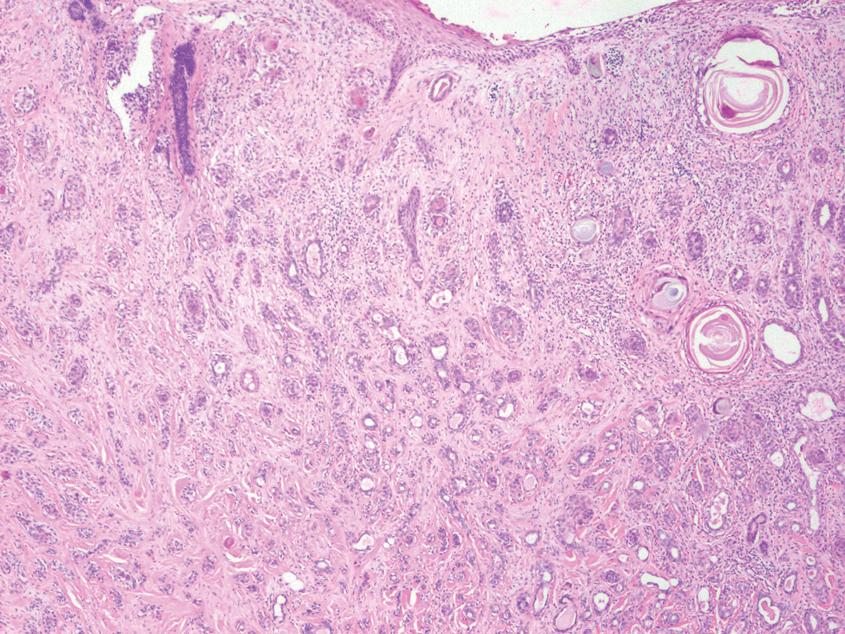

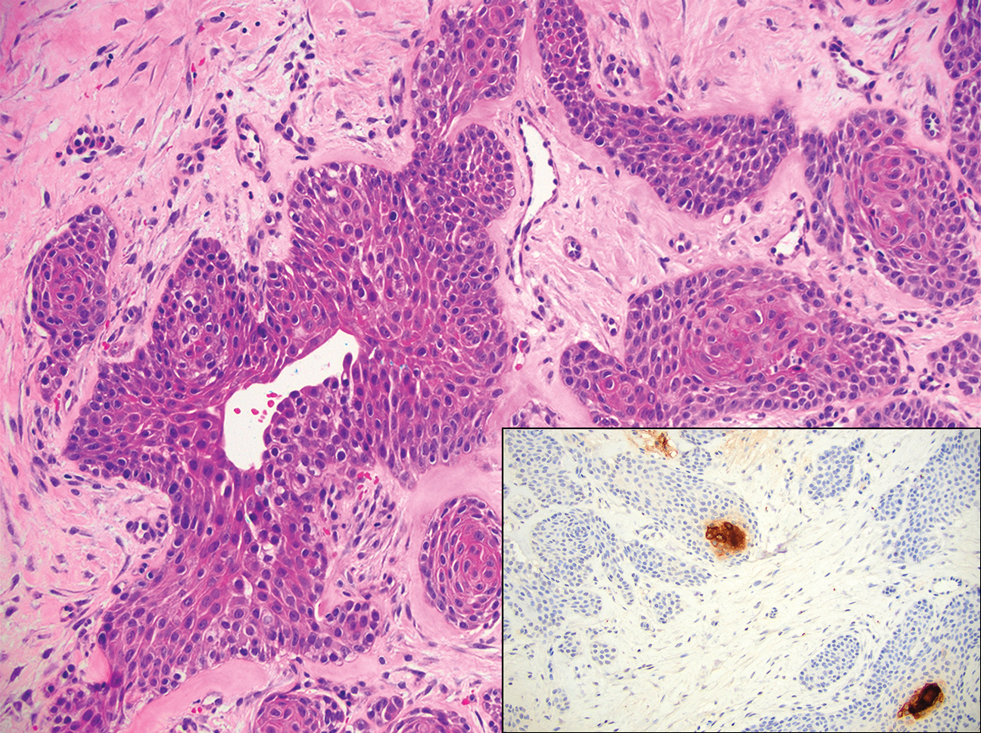

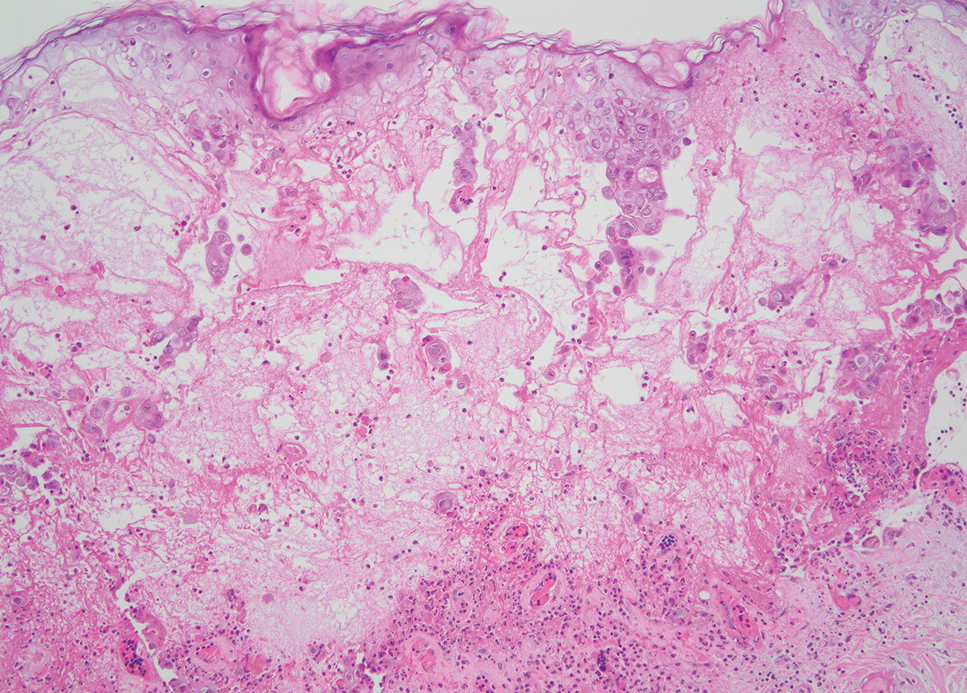

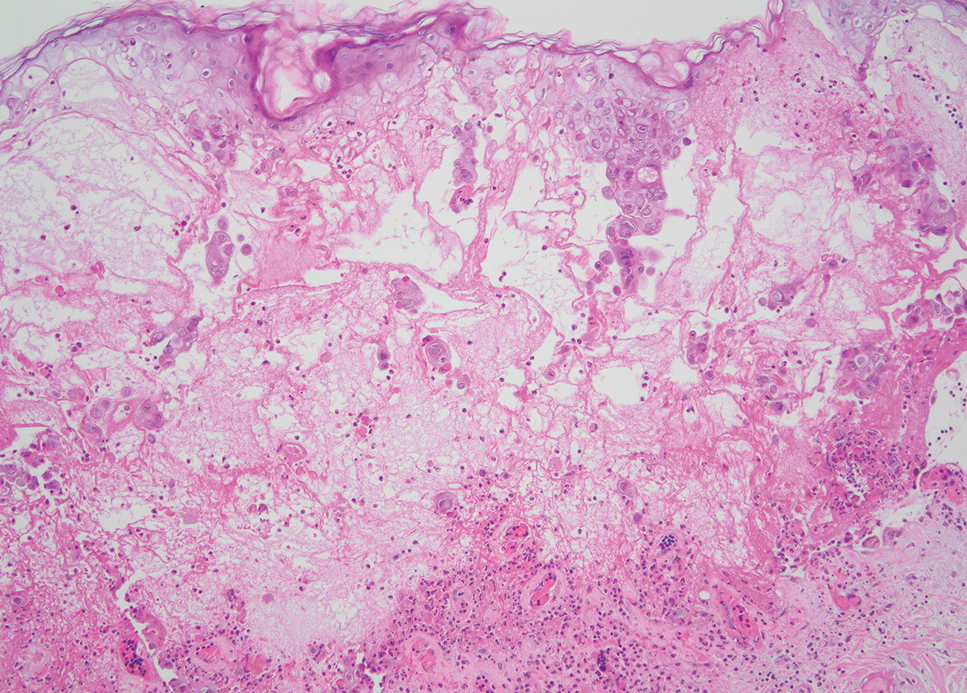

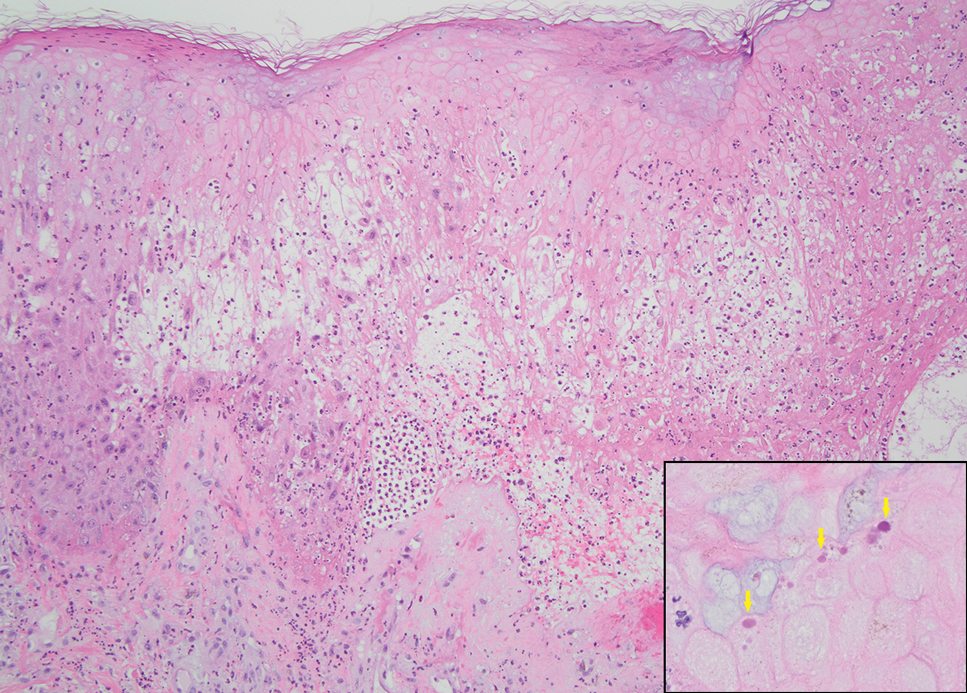

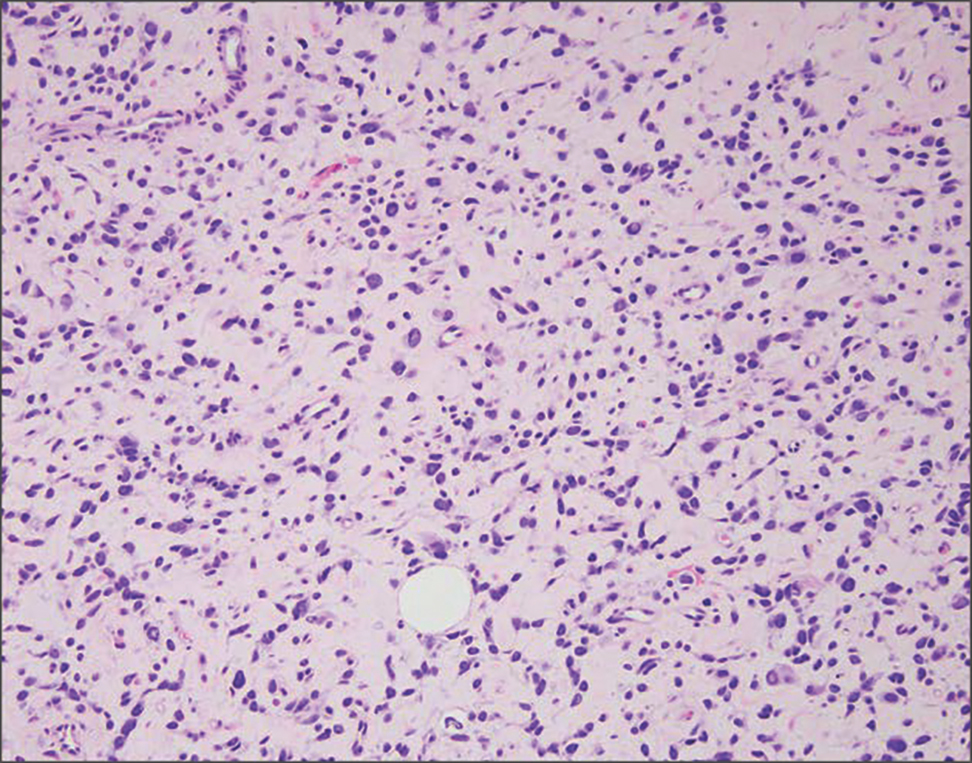

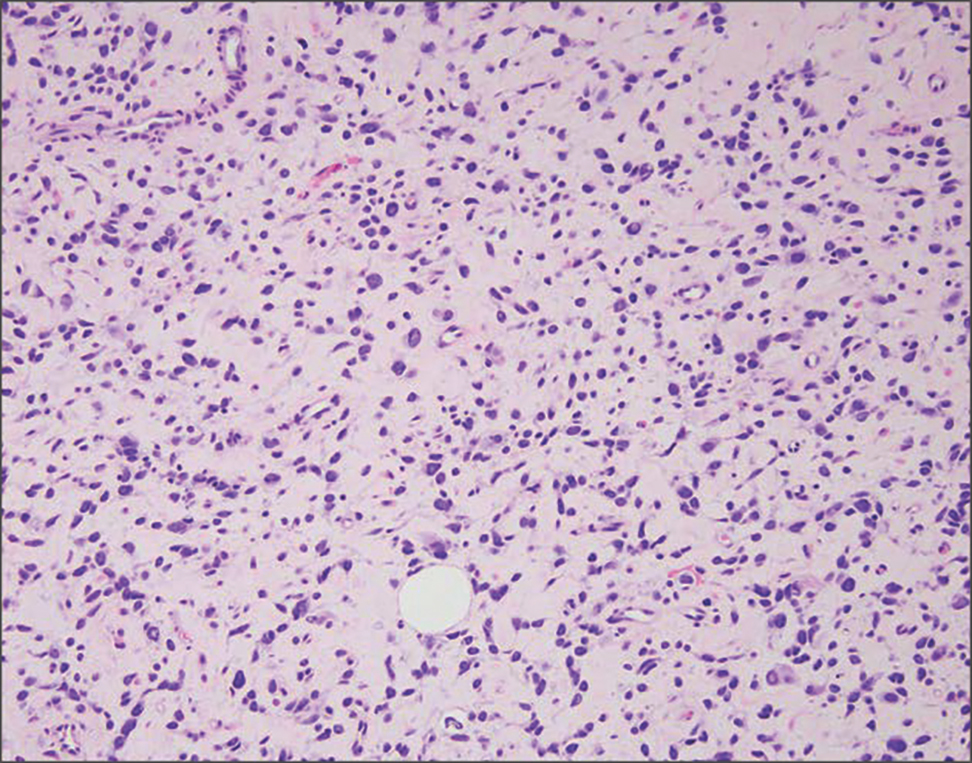

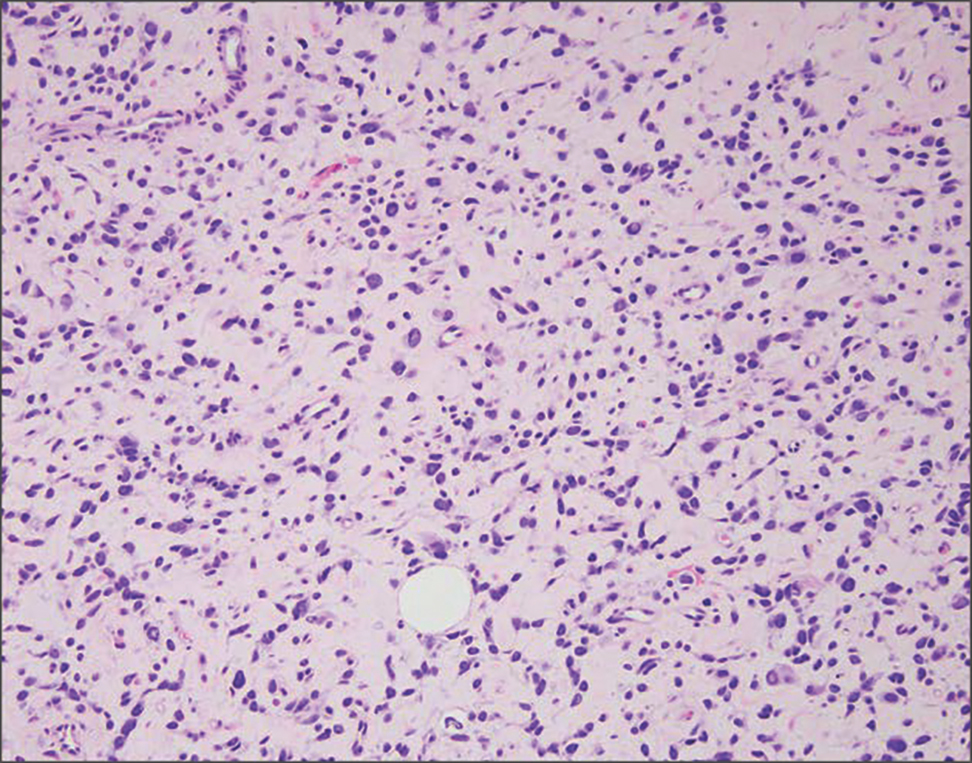

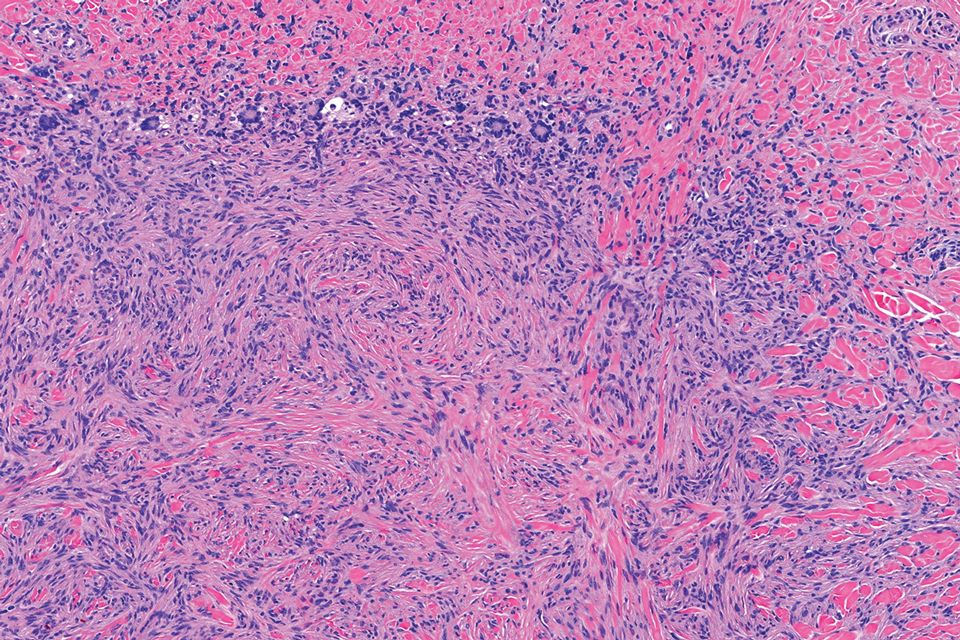

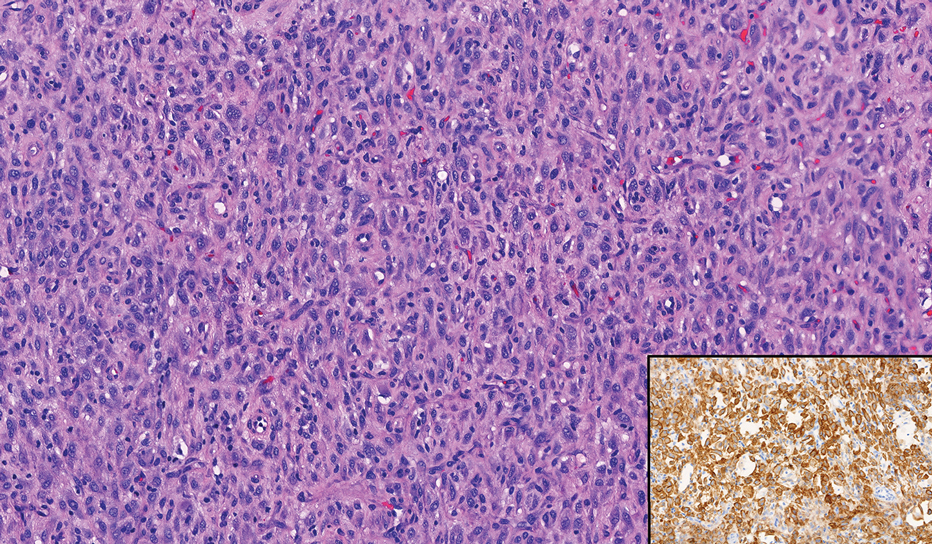

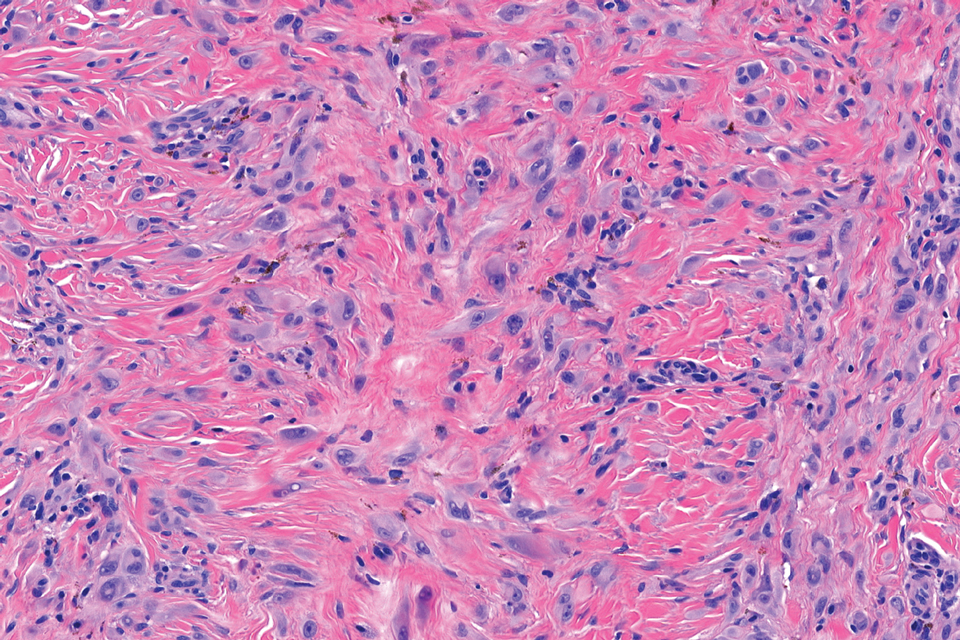

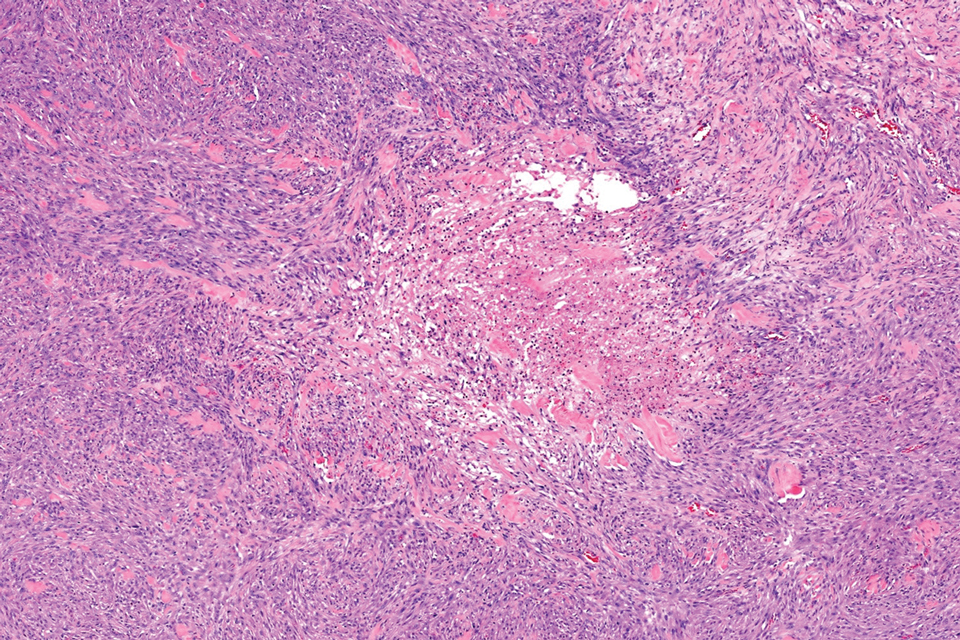

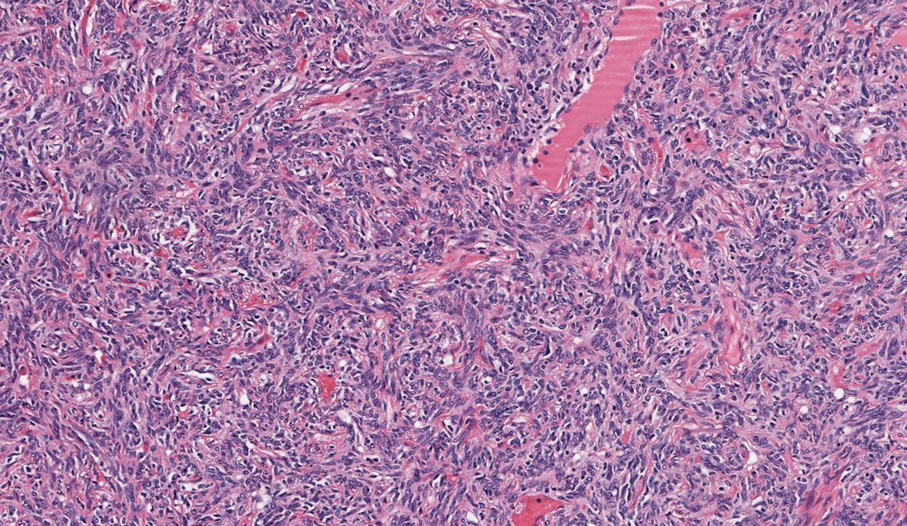

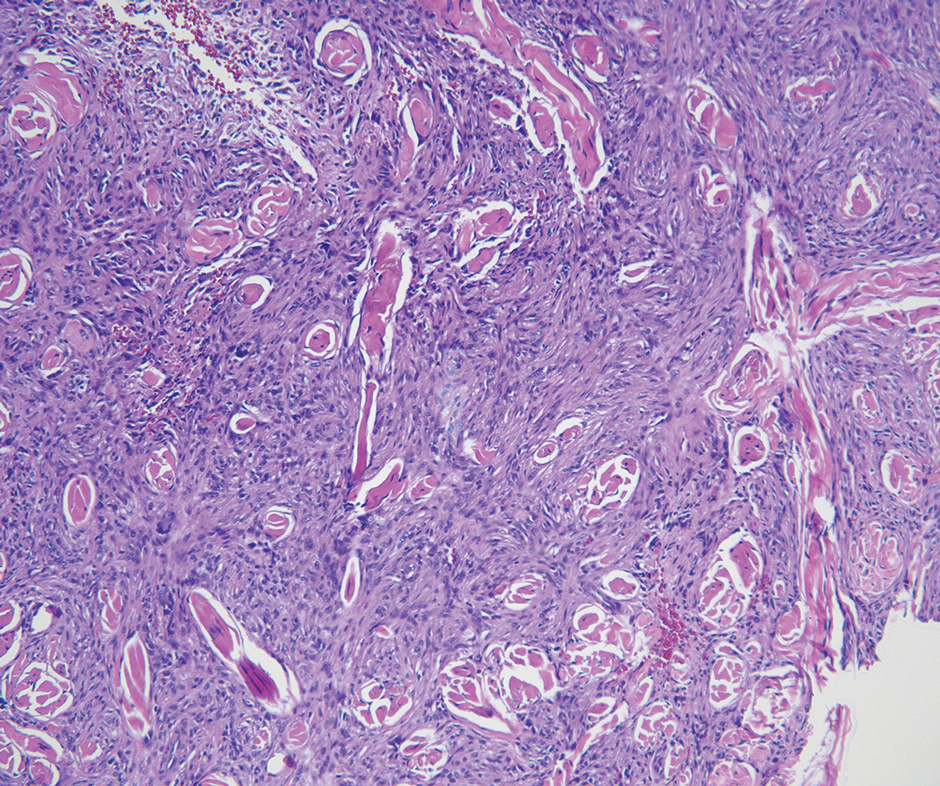

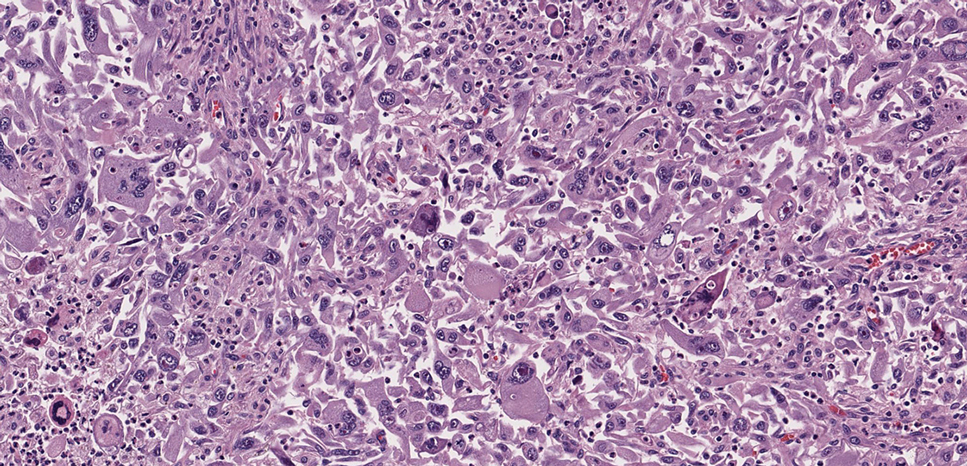

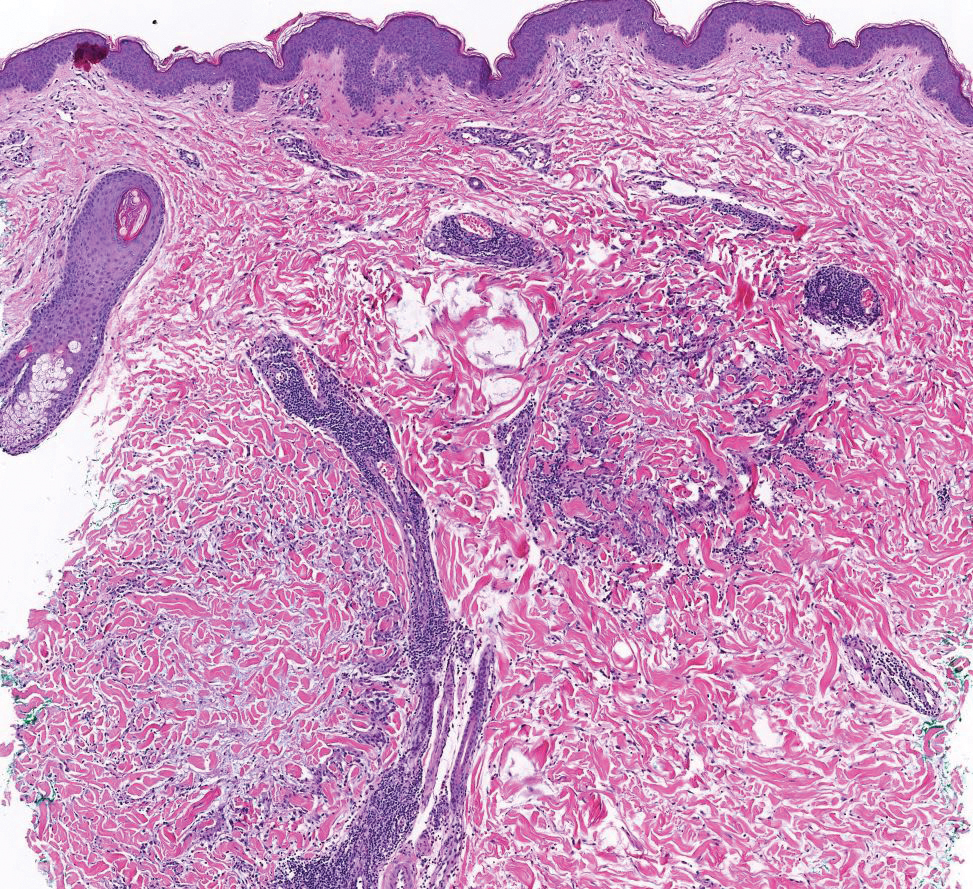

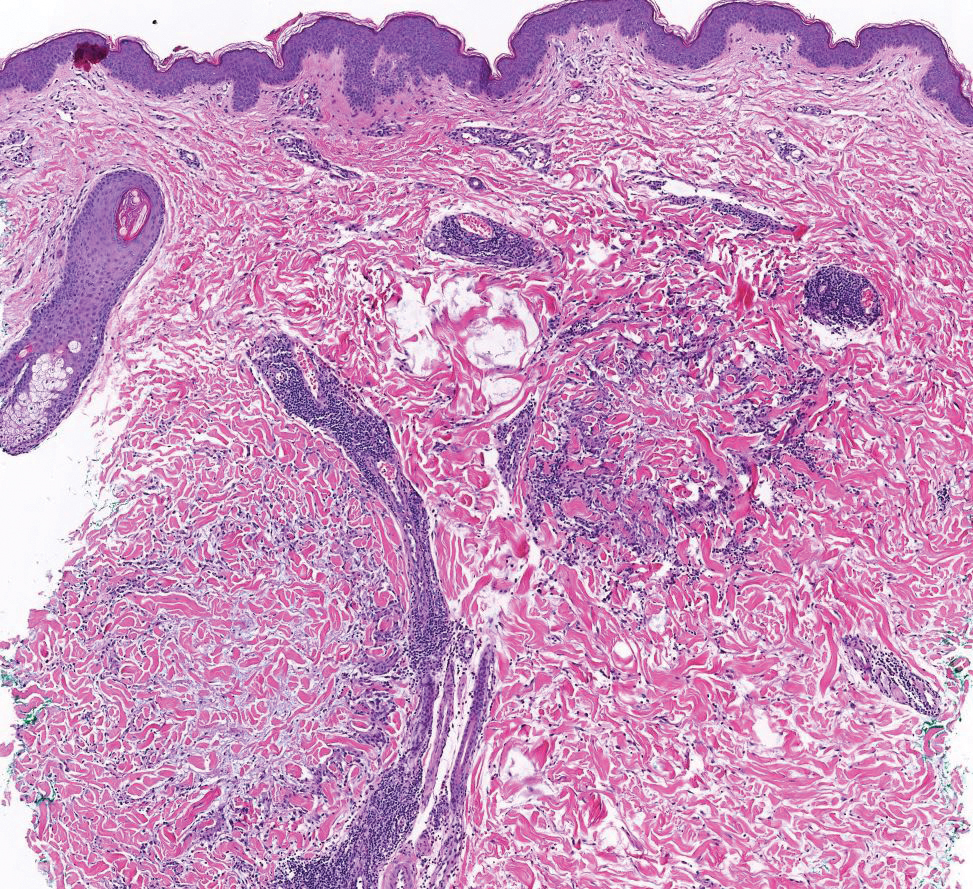

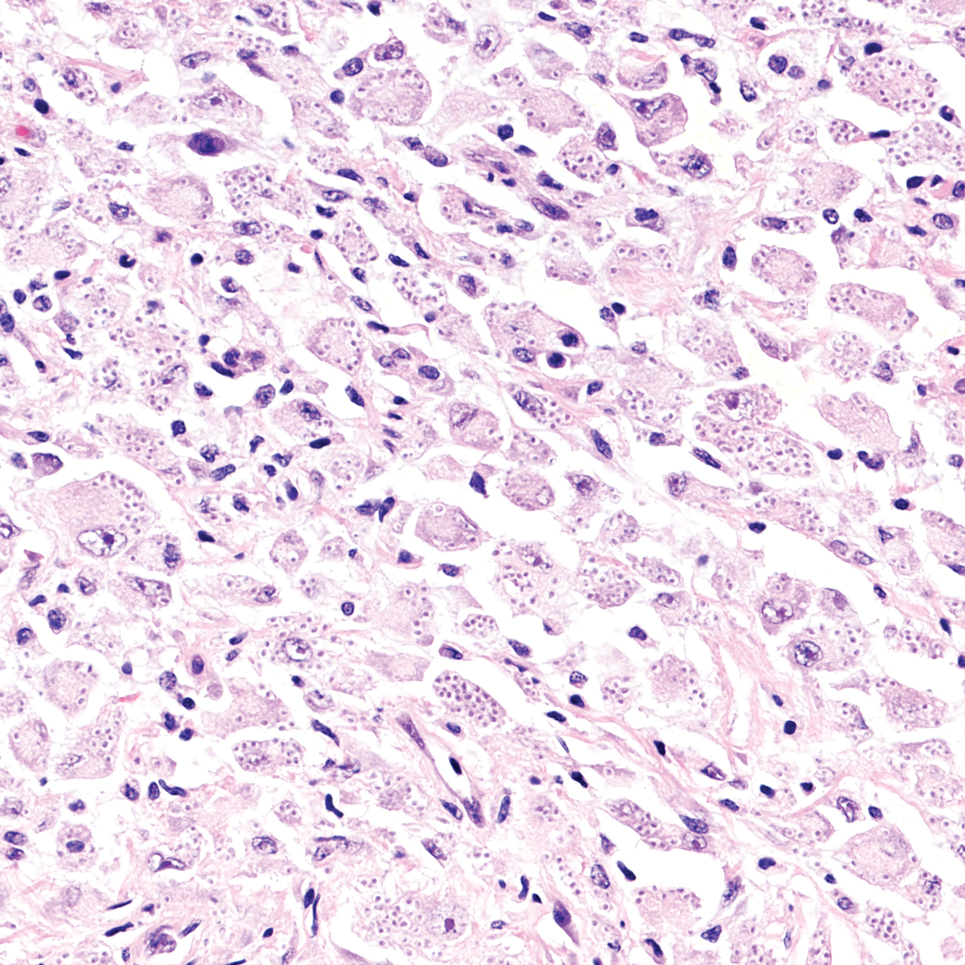

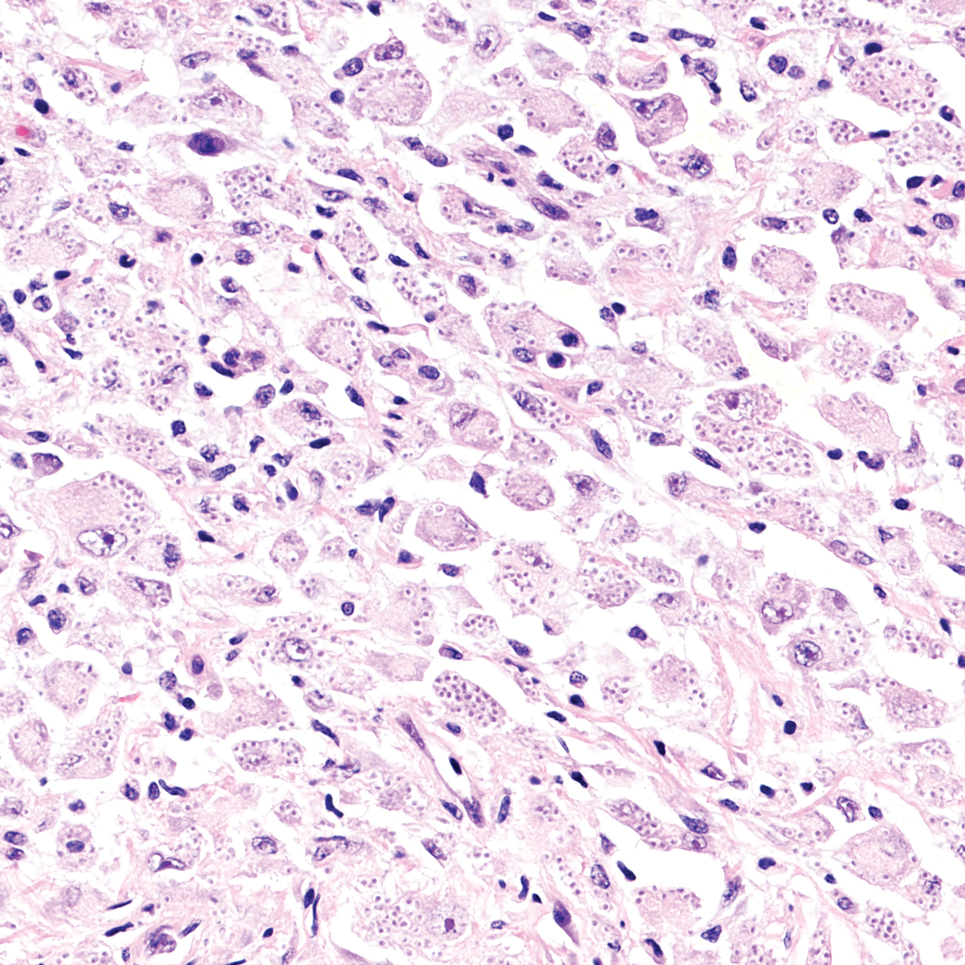

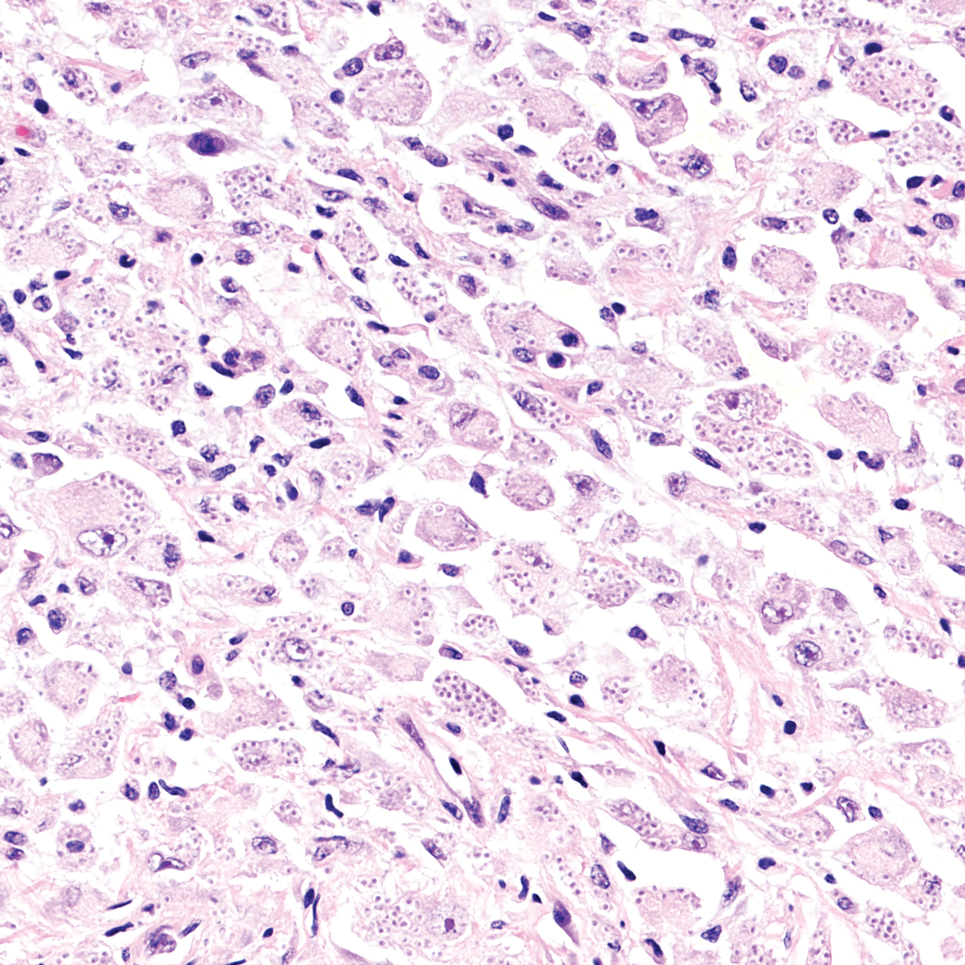

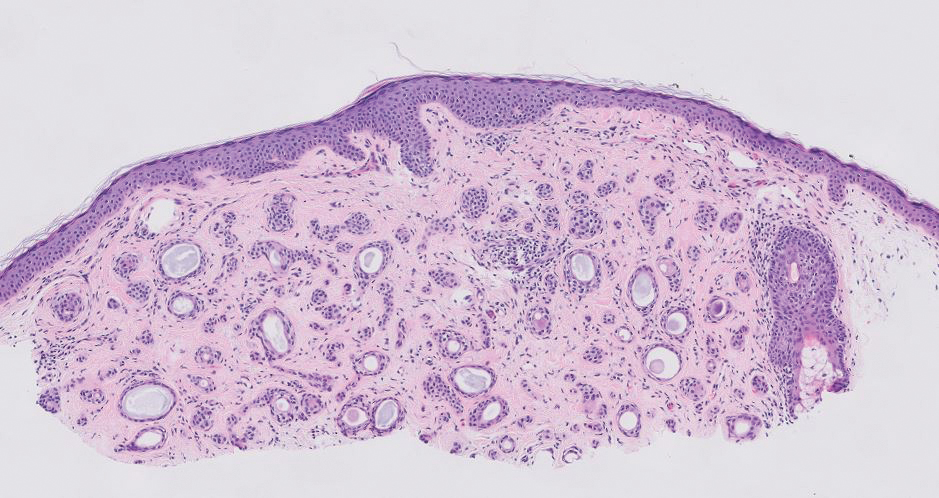

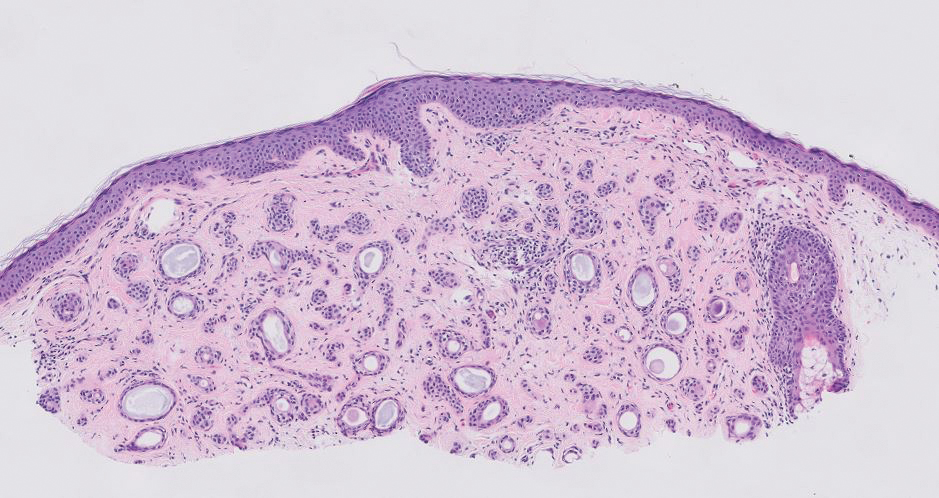

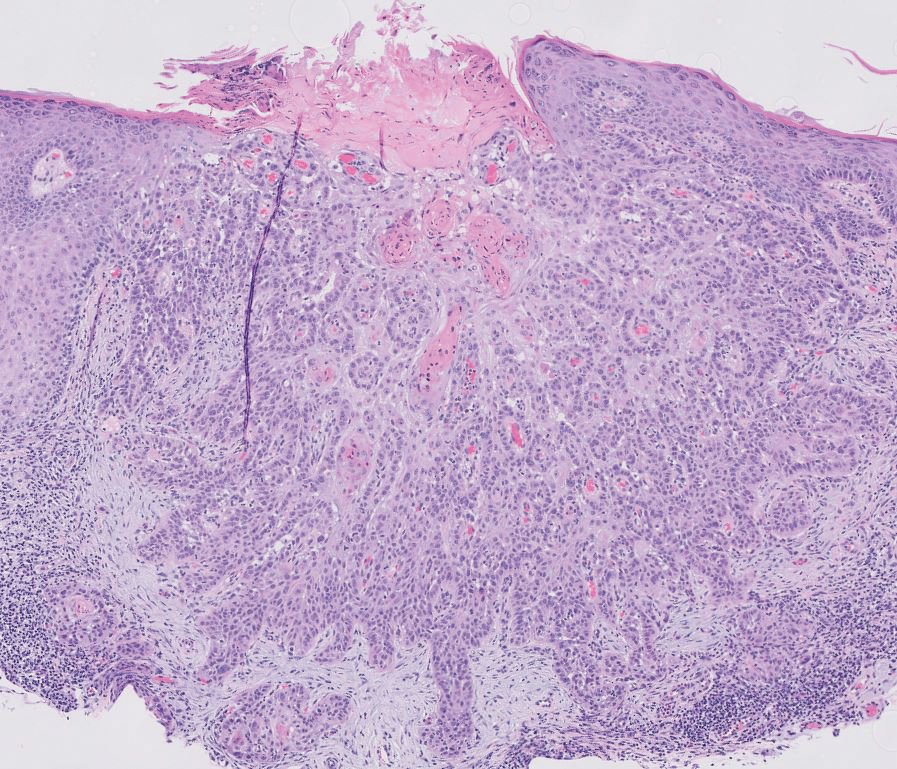

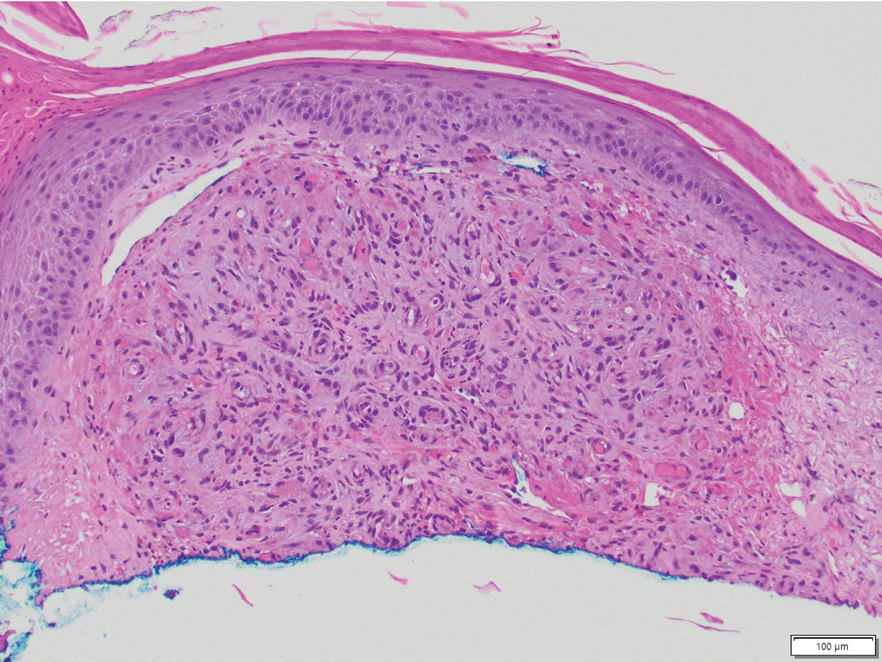

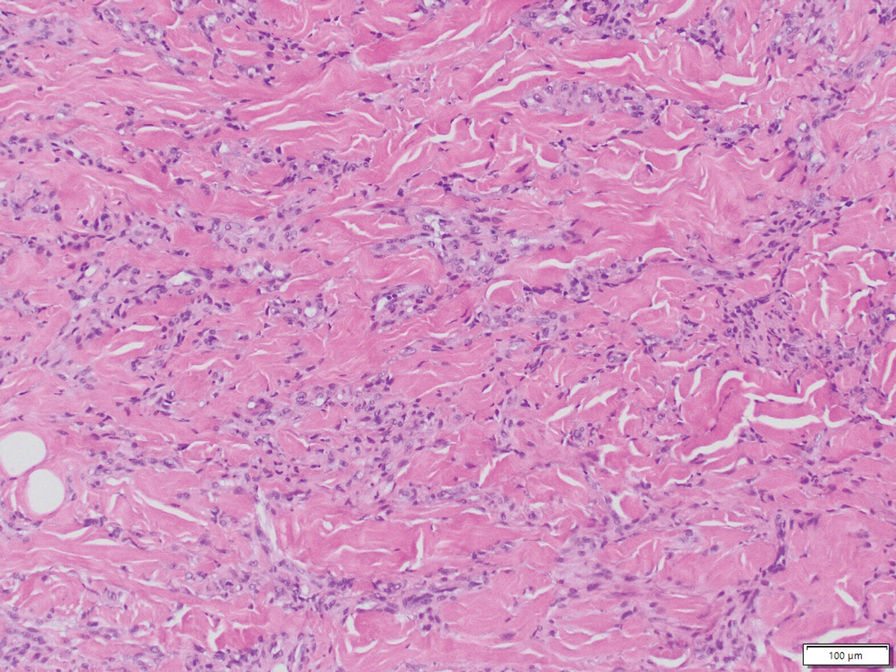

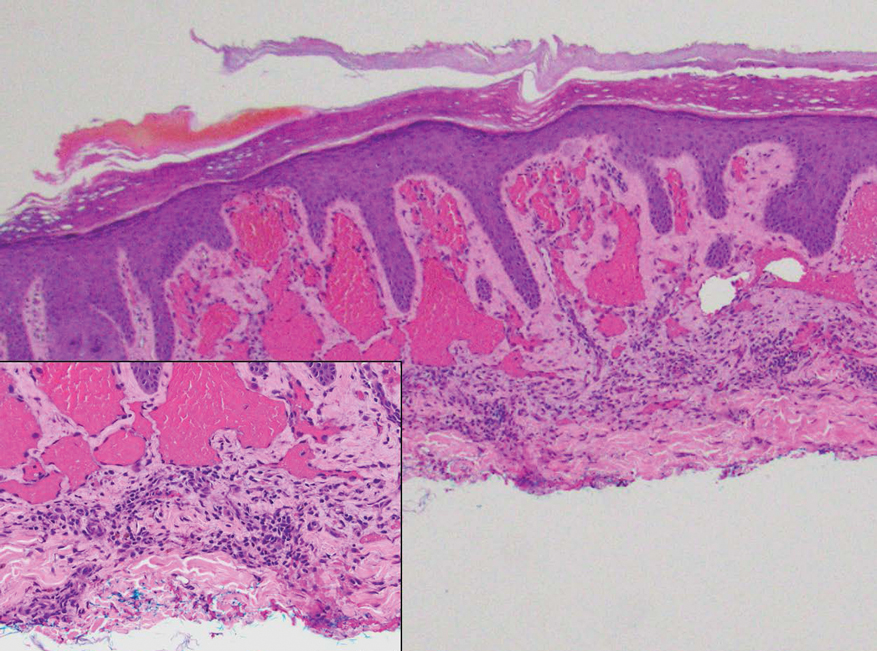

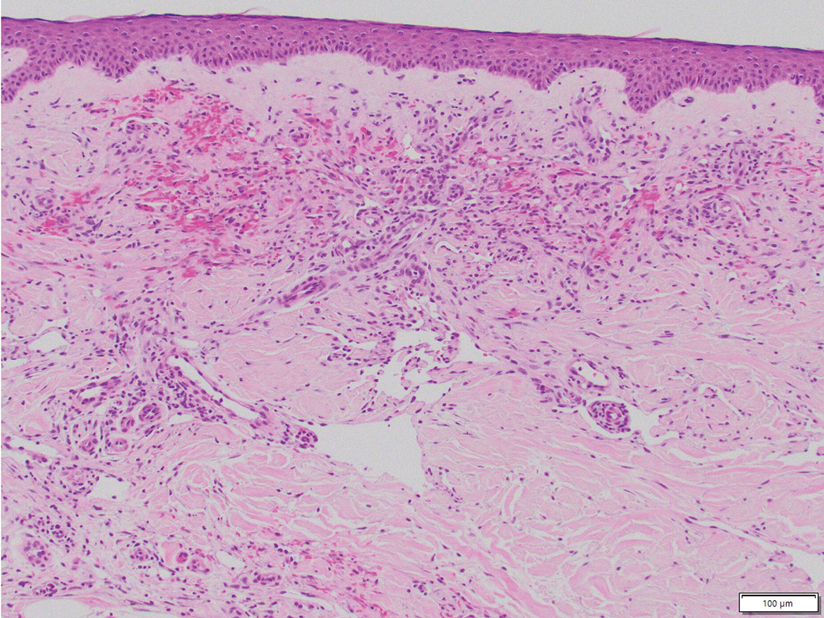

Mycosis fungoides is a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma characterized by proliferation of CD4+ T cells.7 In the early stages of MF, patients may present with multiple erythematous and scaly patches, plaques, or nodules that most commonly develop on unexposed areas of the skin, but specific variants frequently may cause lesions on the face or scalp.8 Tumors may be solitary, localized, or generalized and may be observed alongside patches and plaques or in the absence of cutaneous lesions.7 The pathologic features of MF include fibrosis of the papillary dermis, individual haloed atypical lymphocytes in the epidermis, and atypical lymphoid cells with cerebriform nuclei (Figure 3).9 Granulomatous MF is characterized by diffuse nodular and perivascular infiltrates of histiocytes with small lymphocytes without atypia, eosinophils, and plasma cells. Small lymphocytes with cerebriform nuclei and larger lymphocytes with hyperconvoluted nuclei also may be seen, in addition to multinucleated histiocytic giant cells. Although MF commonly manifests with epidermotropism, it typically is absent in granulomatous MF (GMF).10 Granulomatous MF may manifest similarly to LL. Noduloulcerative lesions and infiltration of atypical lymphocytes into the epidermis (epidermotropism) are much more common in GMF than in LL; however, although ulcerative nodules are not a common feature in patients with leprosy (except during reactional states [ie, Lucio phenomenon]) or secondary to neuropathies, they also can occur in LL.11 In GMF, the infiltrate does not follow a specific pattern, whereas LL infiltrates tend to follow a nerve distribution. Treatment for MF is determined by disease severity.12 First-line therapy includes local corticosteroids and phototherapy with UVB irradiation.

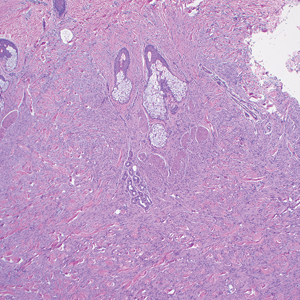

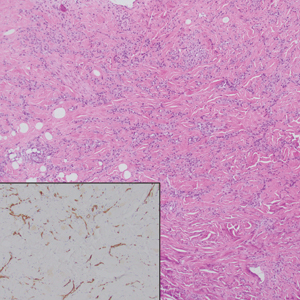

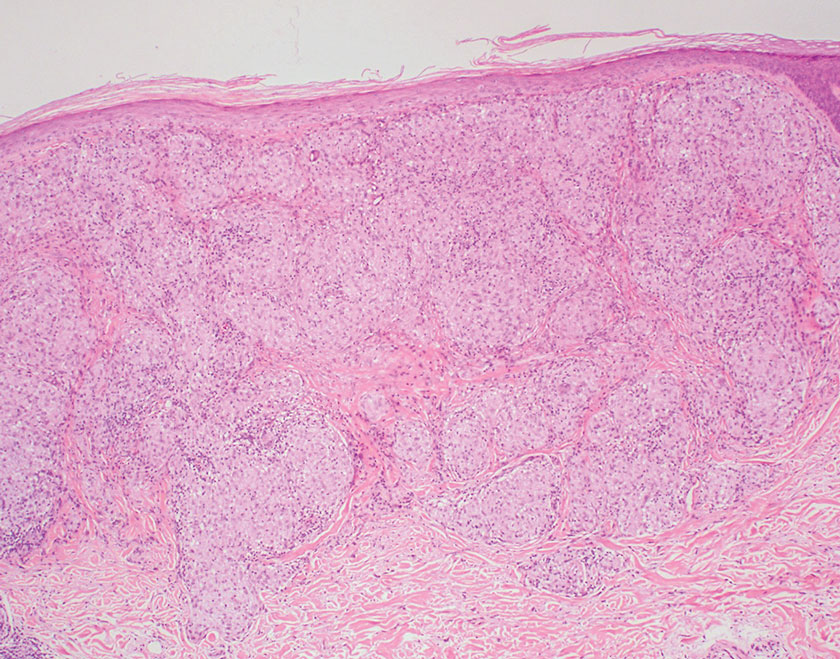

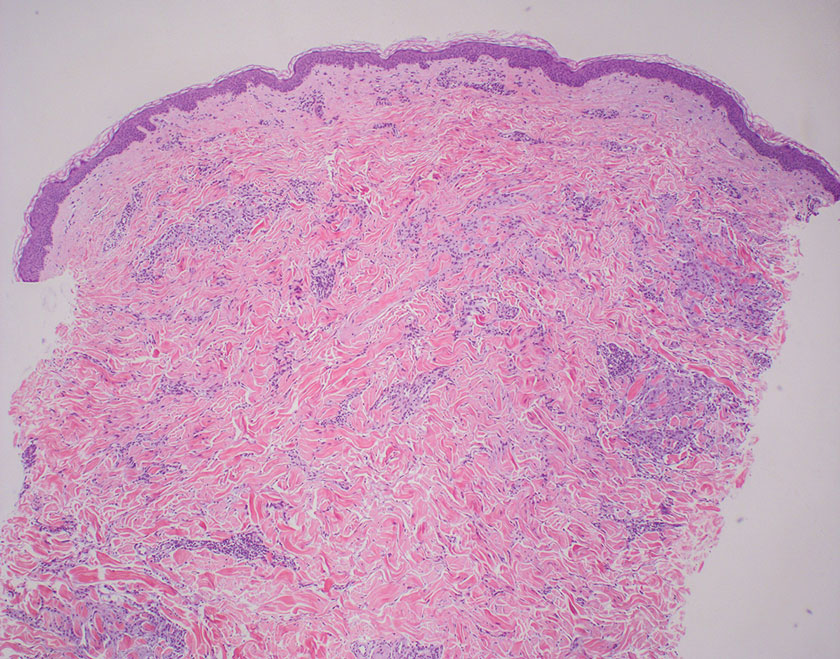

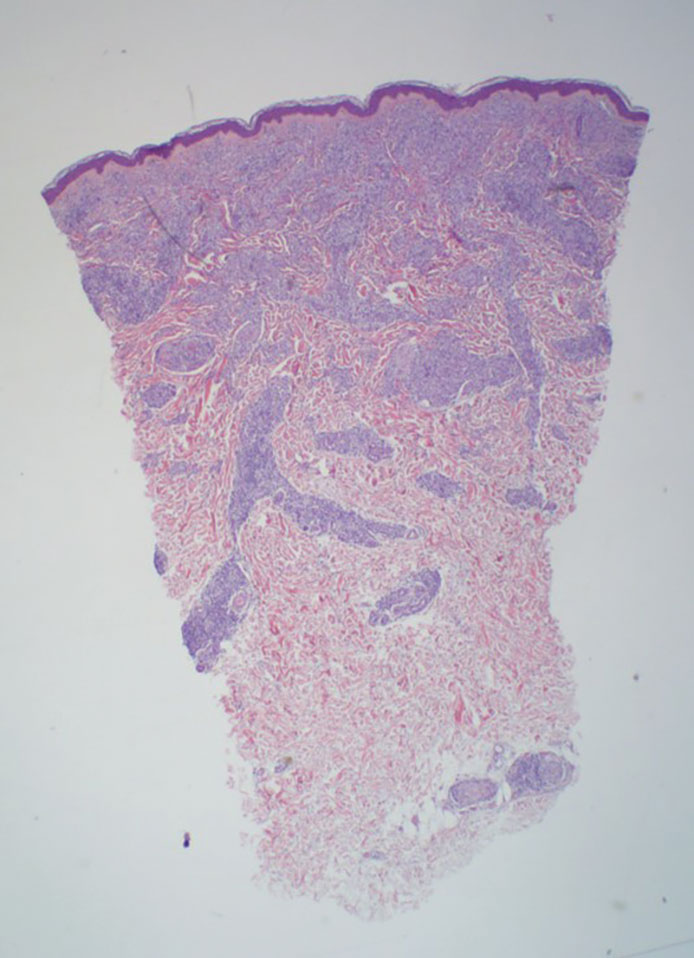

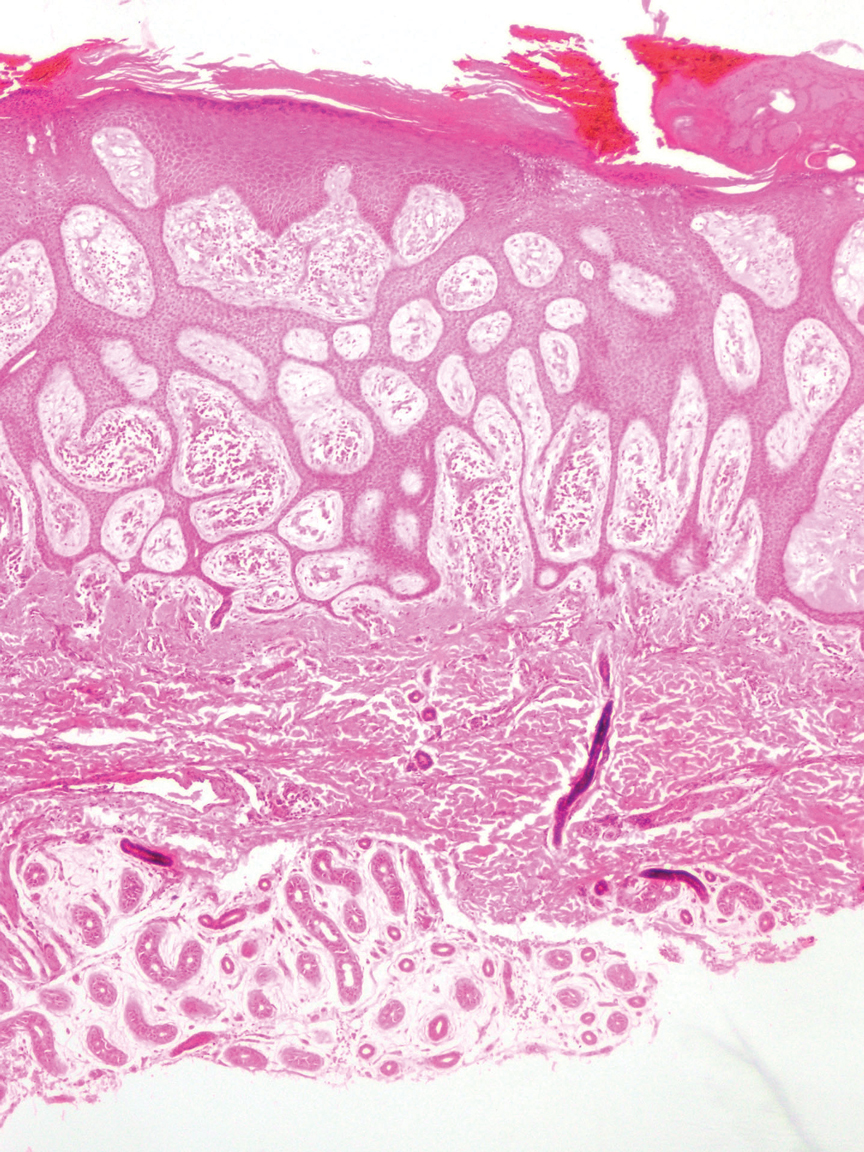

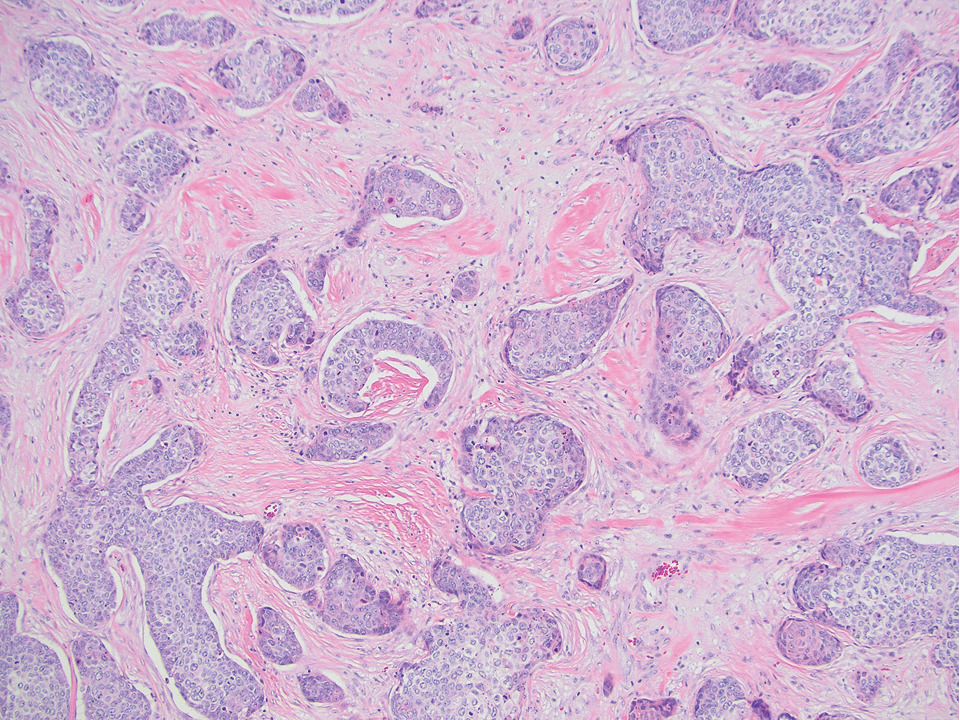

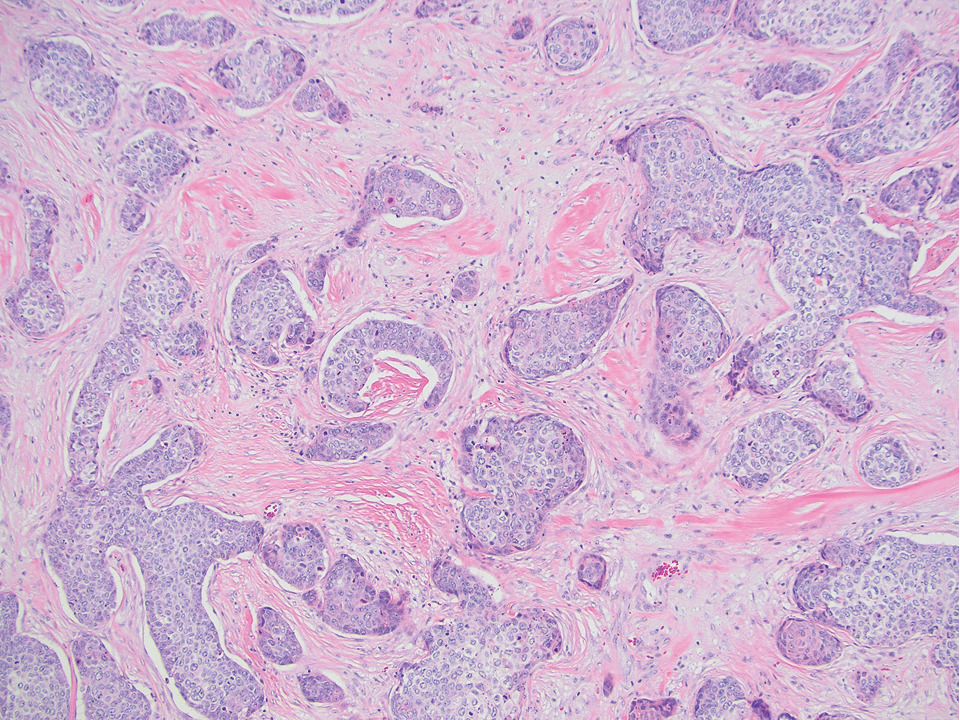

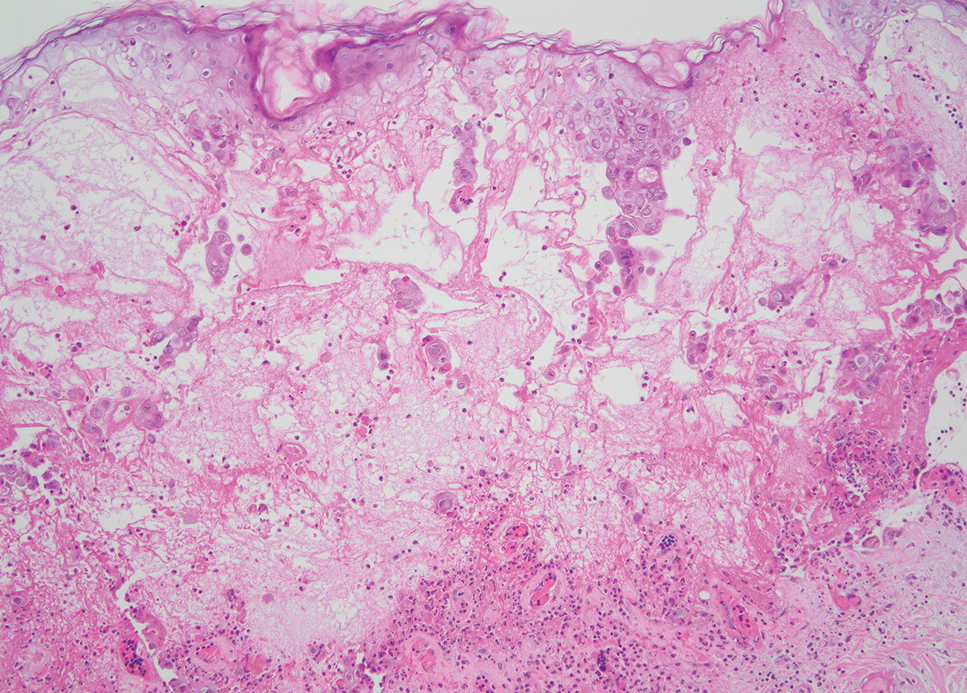

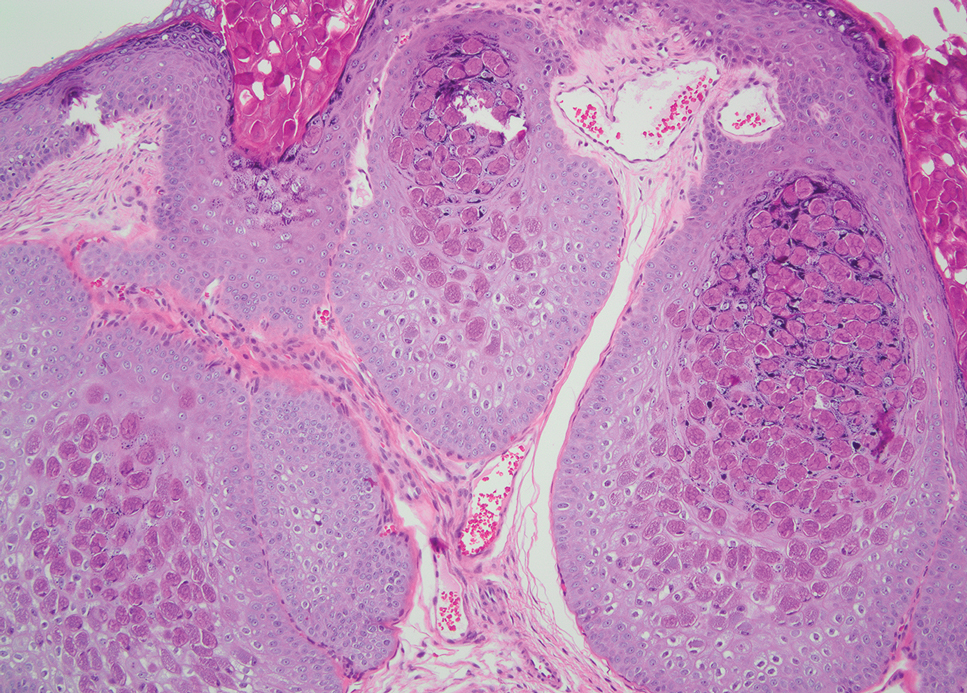

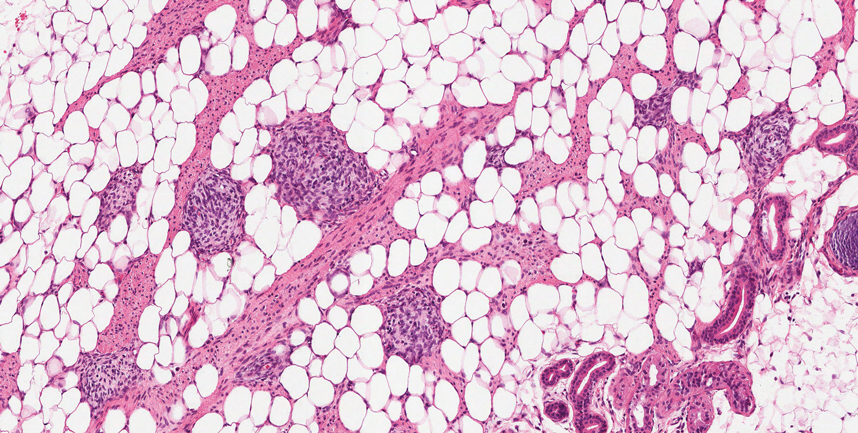

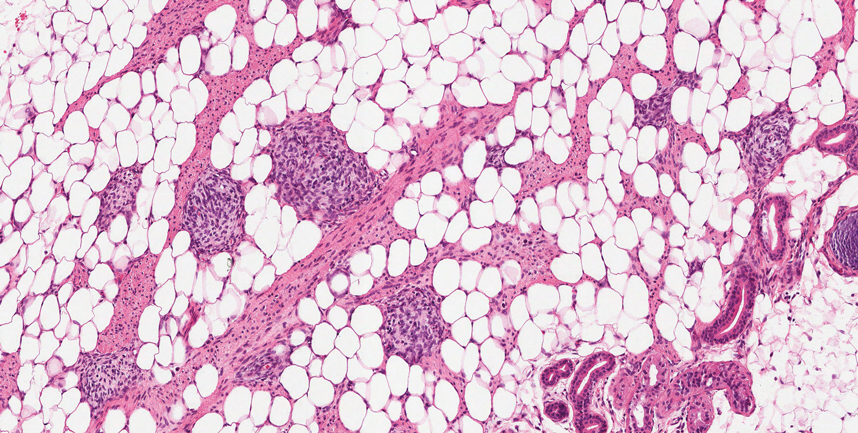

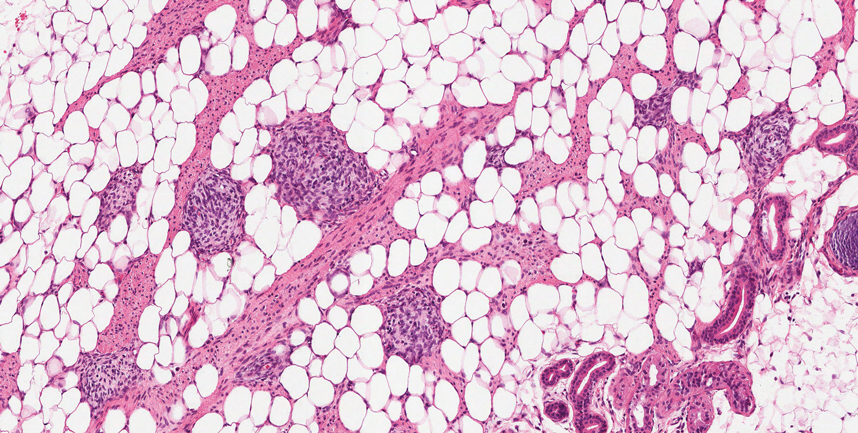

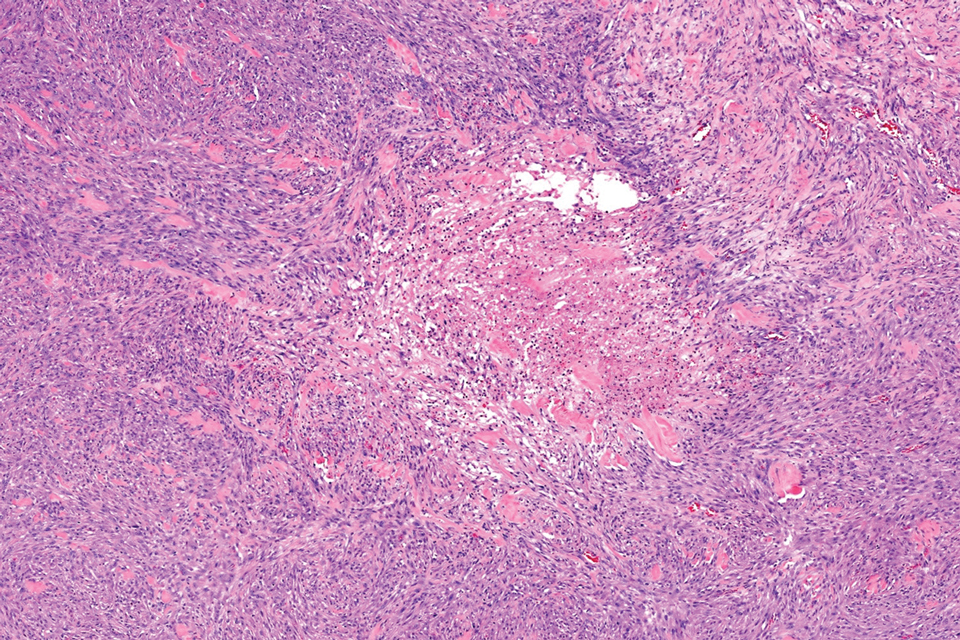

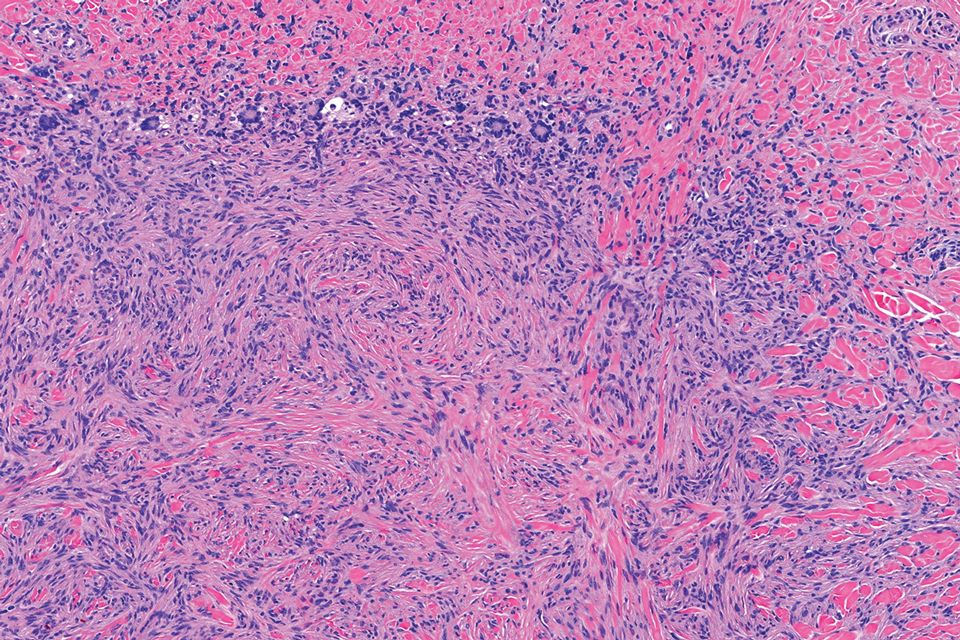

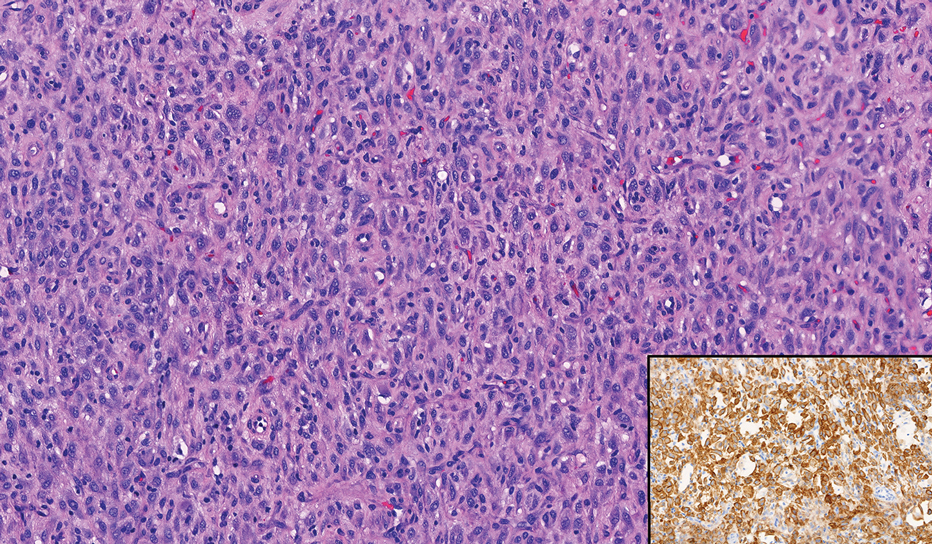

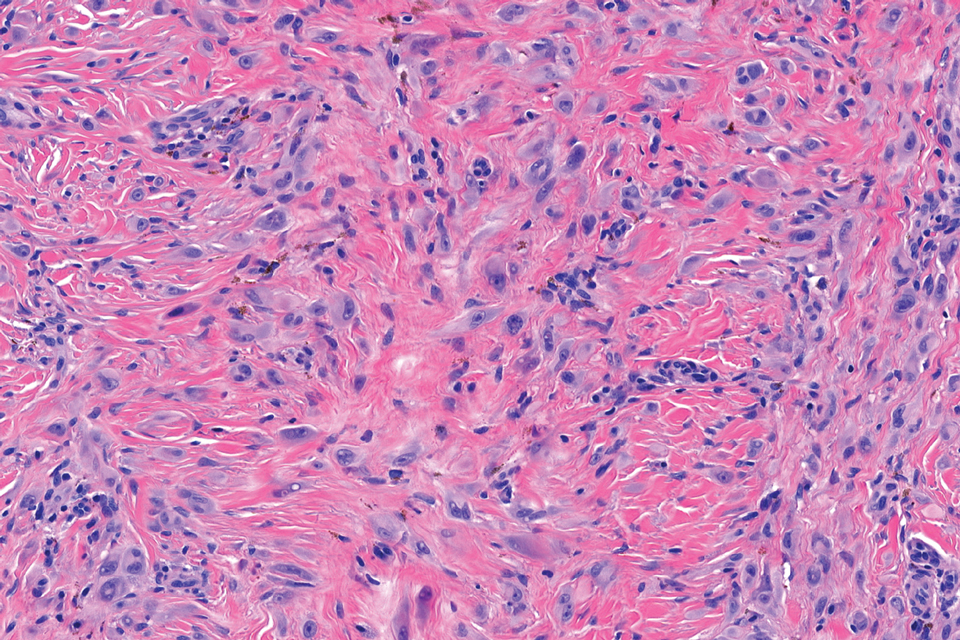

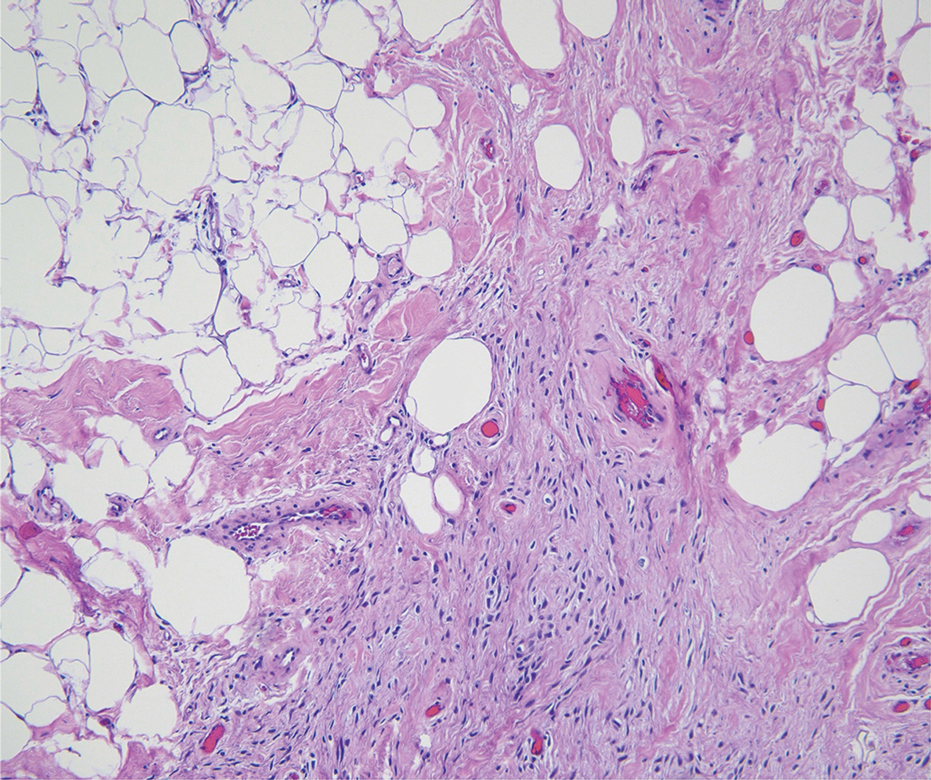

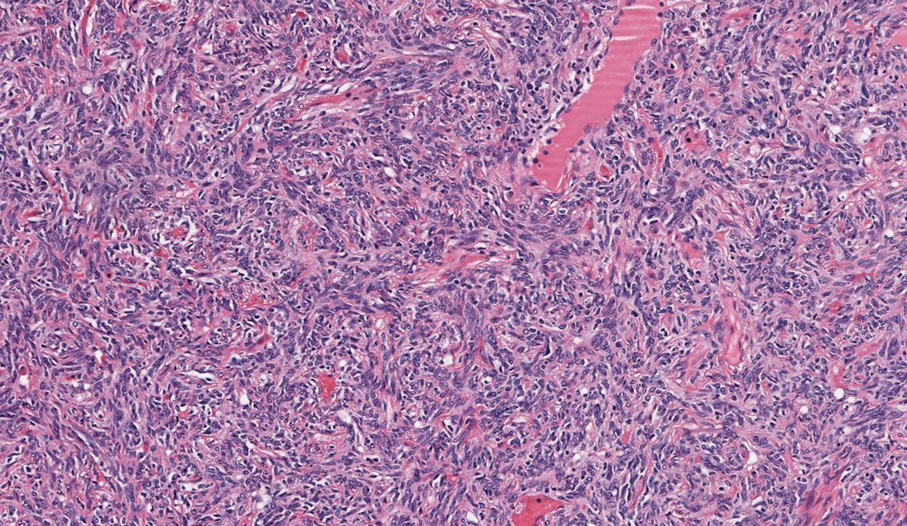

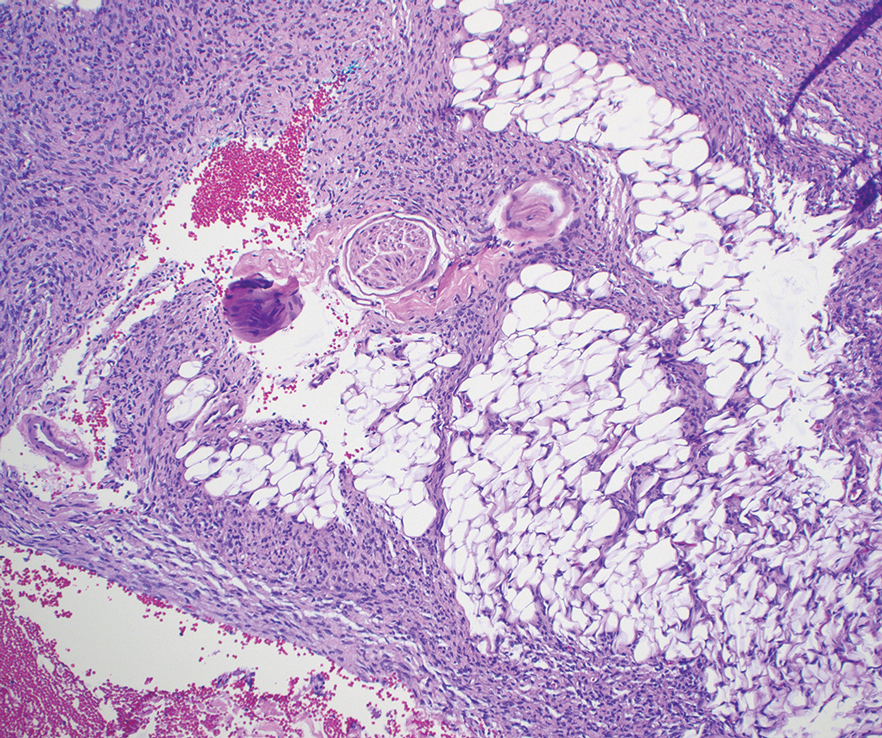

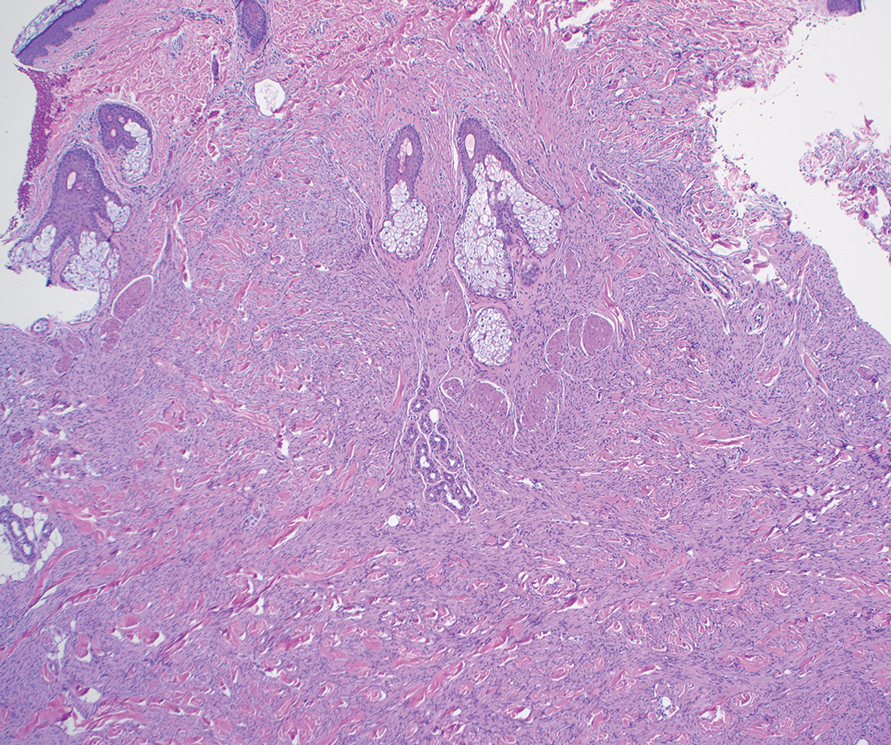

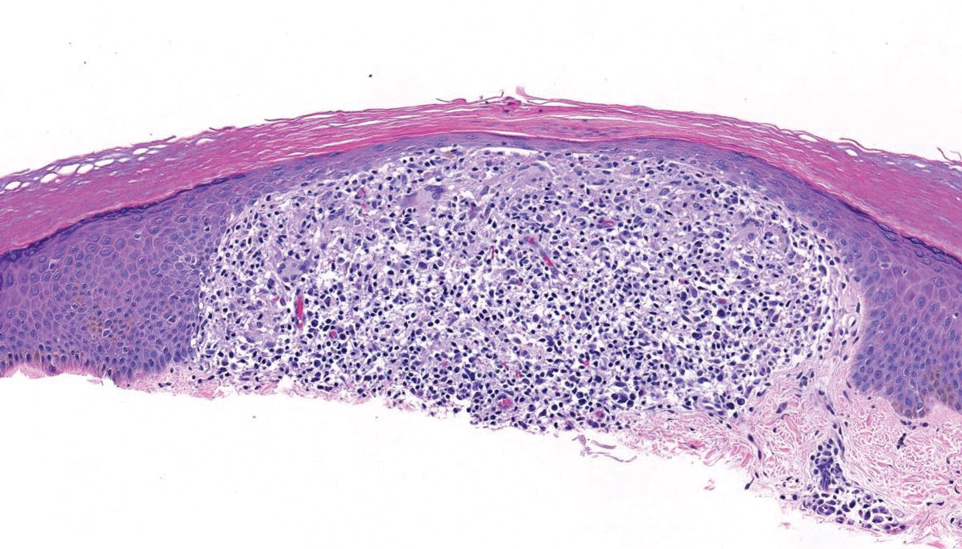

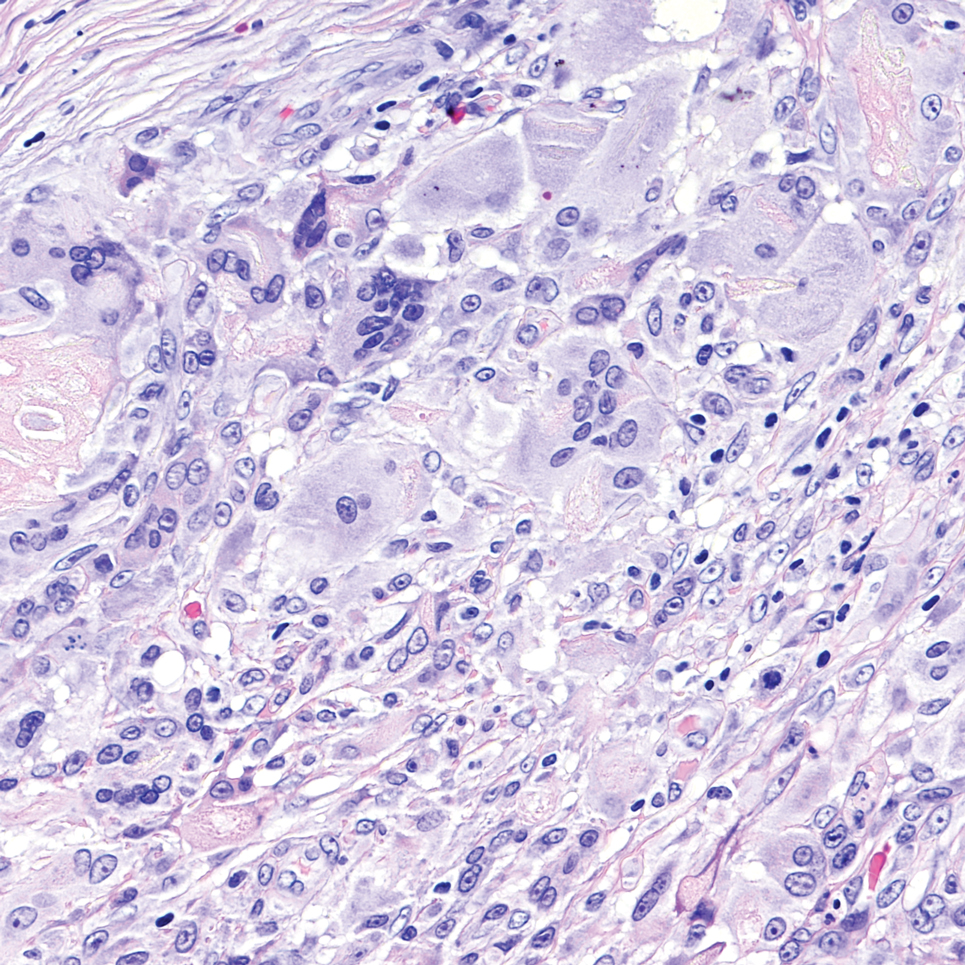

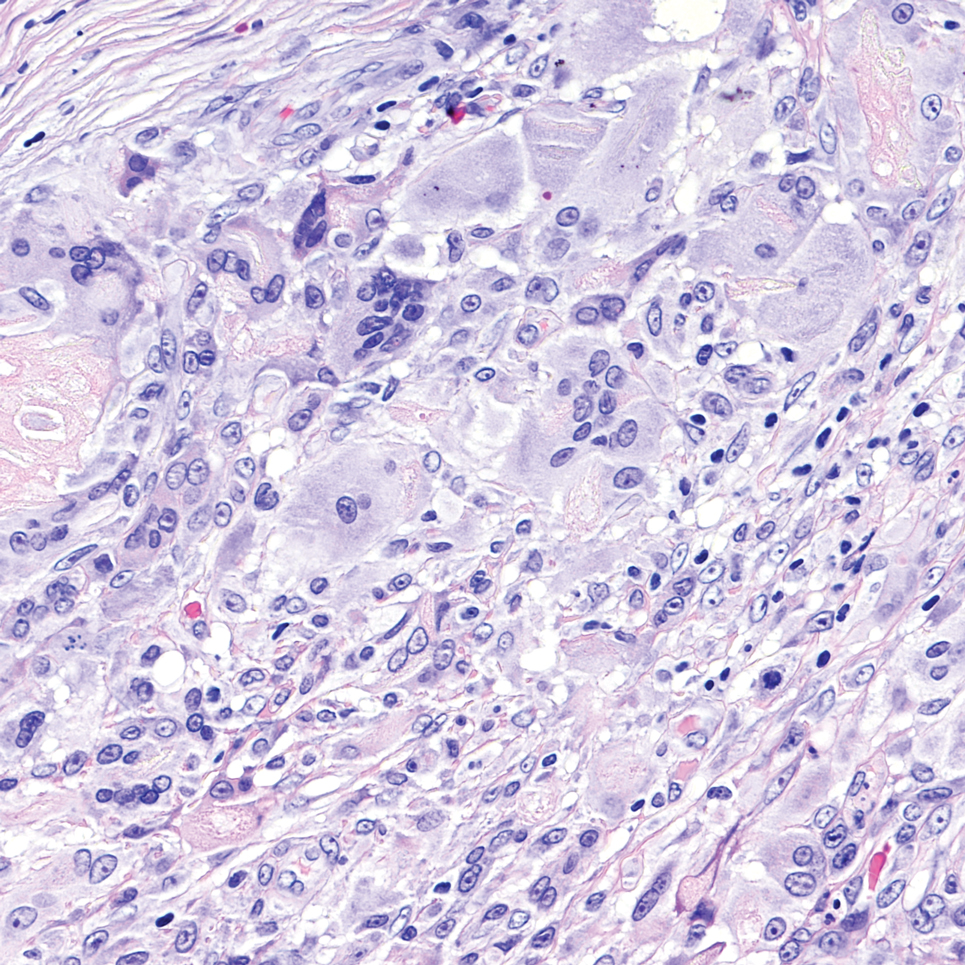

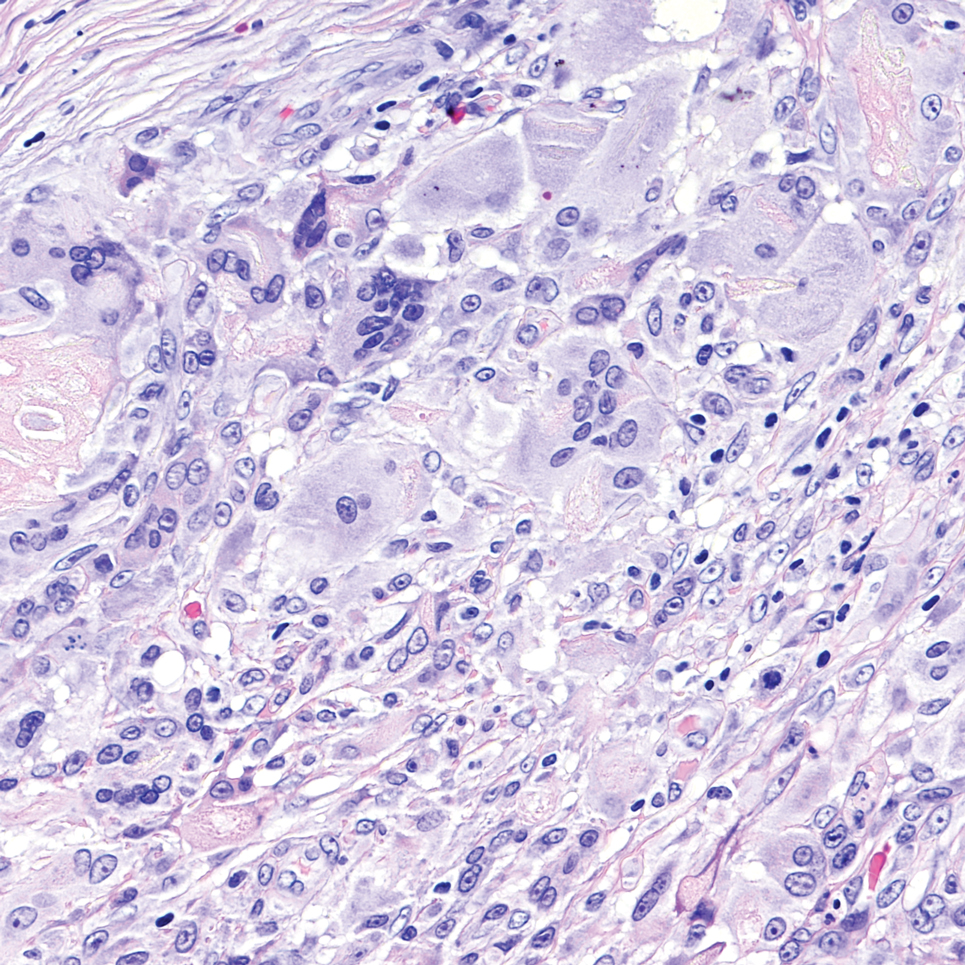

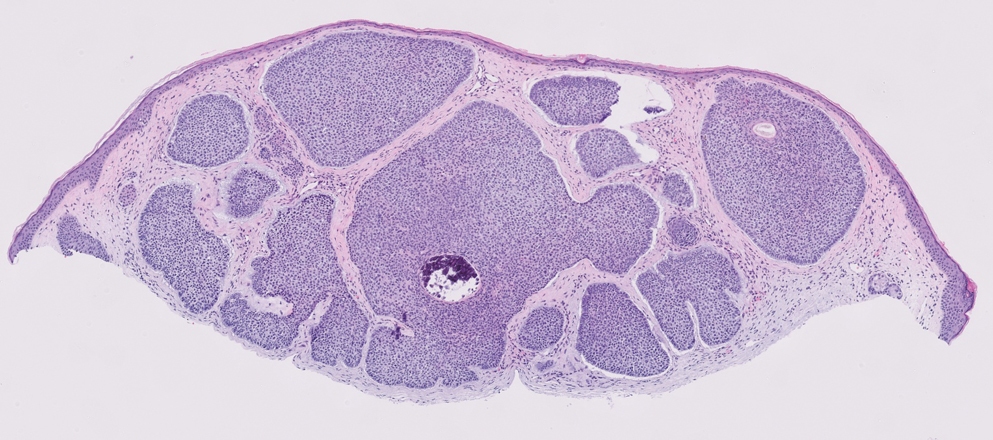

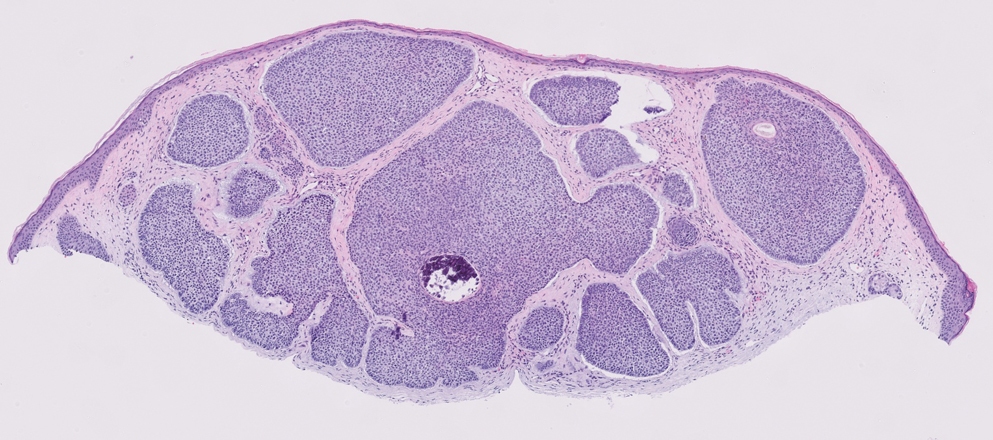

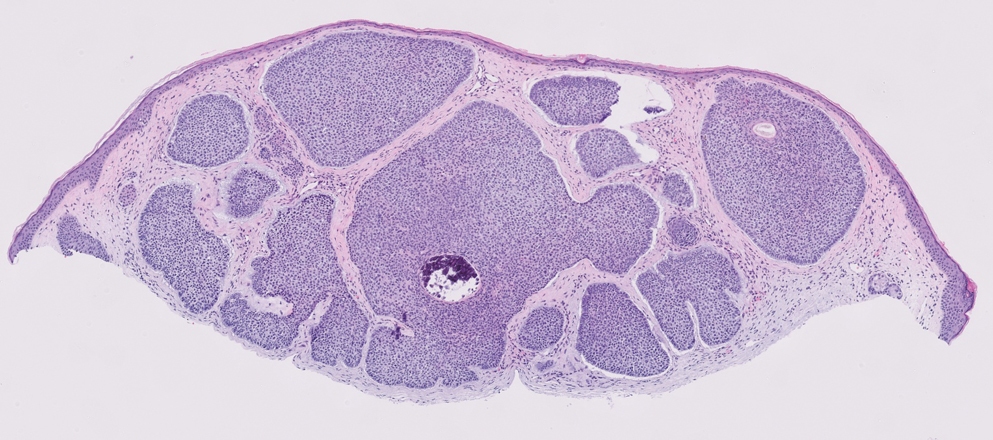

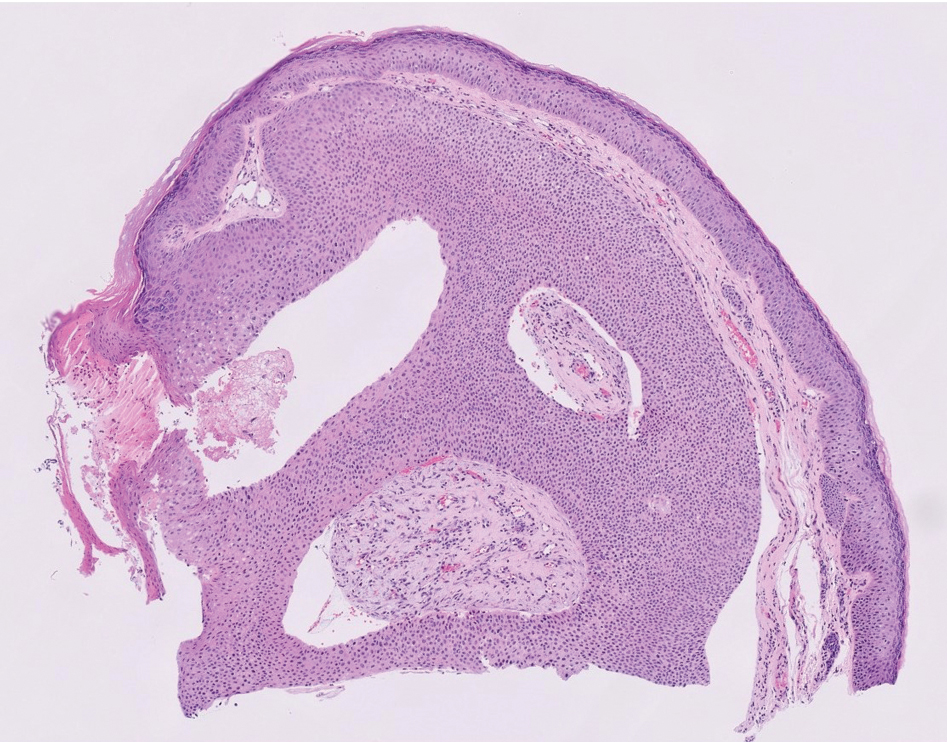

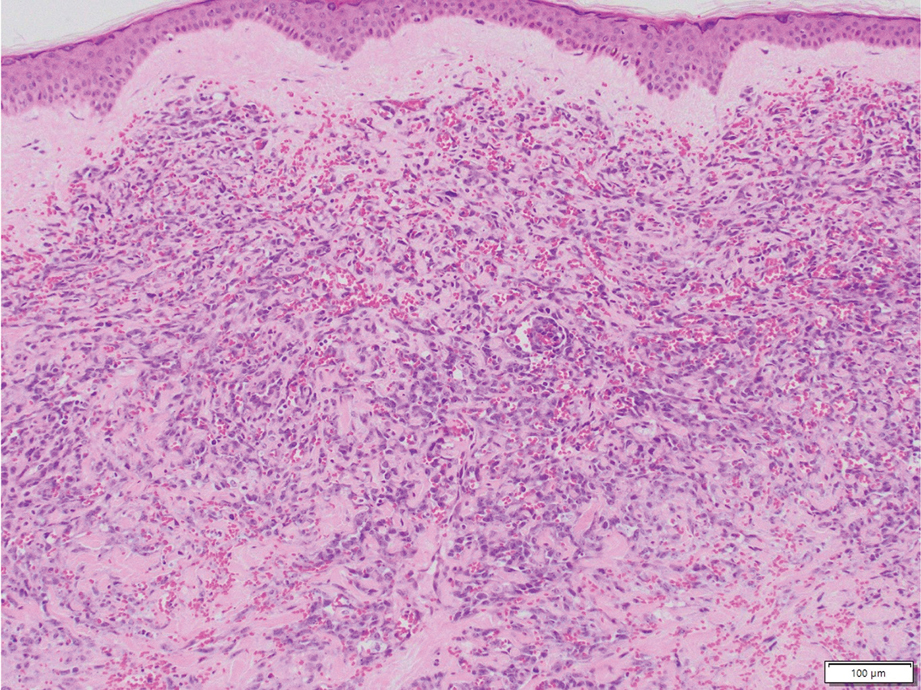

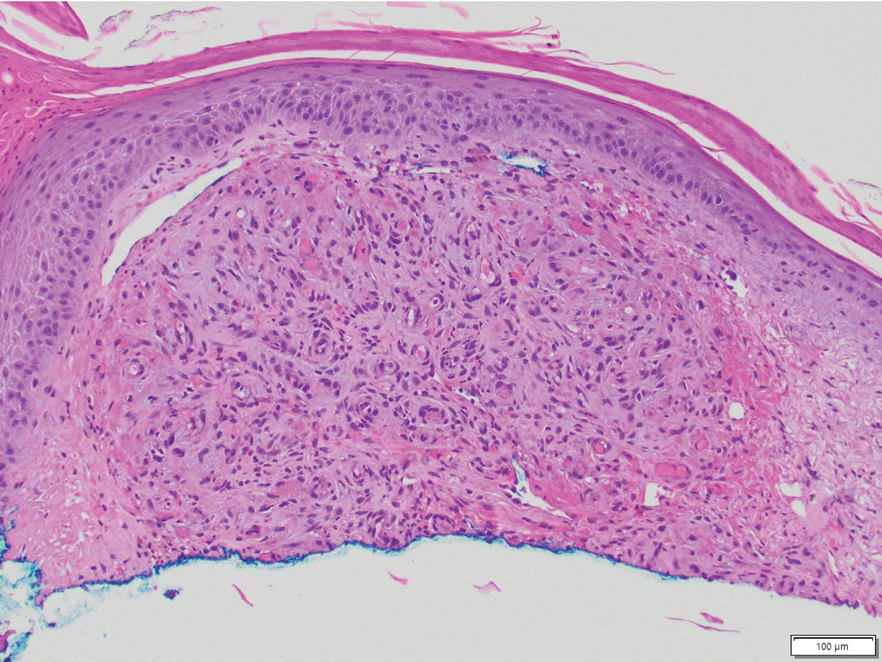

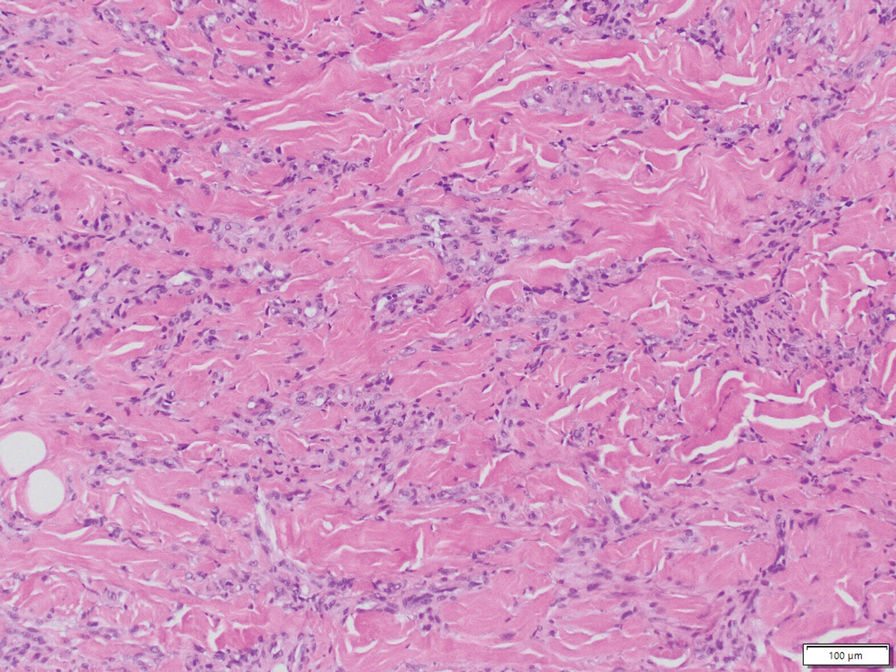

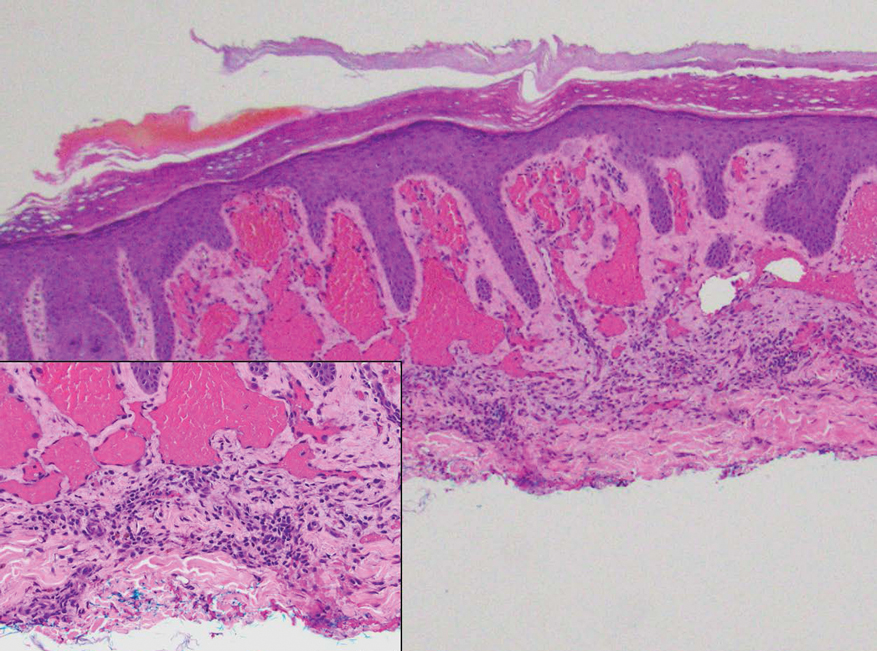

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease that demonstrates nonspecific clinical manifestations affecting the lungs, eyes, liver, and skin.13 Environmental exposures to silica and inorganic matter have been linked to an increased risk for sarcoidosis, with patients presenting with fatigue, fever, and arthralgia.13 Skin manifestations include subcutaneous nodules, polymorphous plaques, and erythema nodosum—nodosum—the most common cutaneous presentation of sarcoidosis. Erythema nodosum manifests as symmetrically distributed, nonulcerative, painful red nodules on the skin, especially the lower legs. The histopathology of sarcoidosis shows noncaseating granulomas with activated T-lymphocytes, epithelioid cells, and multinucleated giant cells (Figure 4). Although granulomas occur in both LL and sarcoidosis, those in sarcoidosis typically consist of epithelioid cells surrounded by a rim of lymphocytes, whereas LL granulomas contain foamy histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. Treatment of sarcoidosis depends on disease progression and generally involves oral corticosteroids, followed by corticosteroid-sparing regimens.

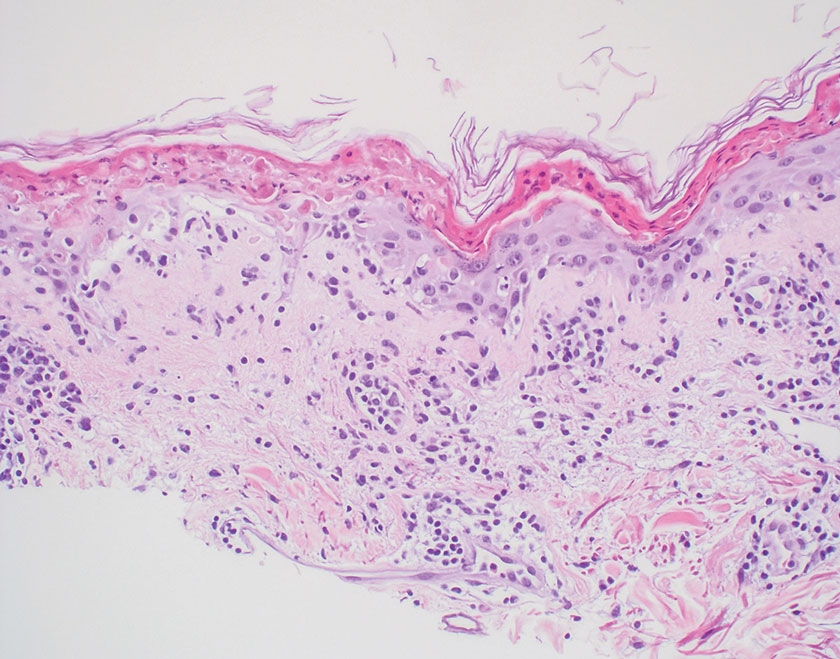

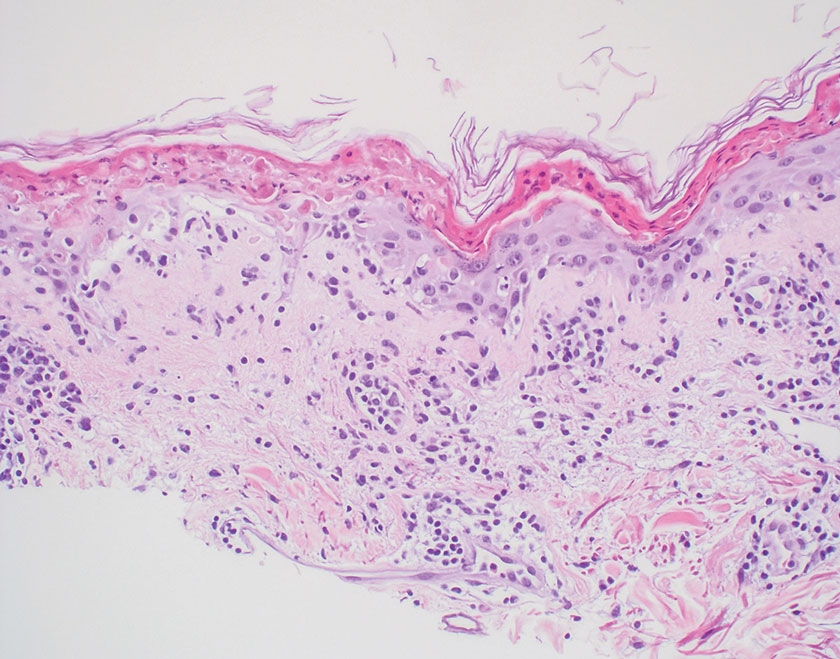

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus is a chronic autoimmune disease that predominantly affects younger women. Common findings in SCLE include red scaly plaques and ring-shaped lesions on sun-exposed areas of the skin.14 Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus primarily is characterized by a photosensitive rash, often with arthralgia, myalgia, and/or oral ulcers; less commonly, a small percentage of patients can experience central nervous system involvement, vasculitis, or nephritis. The histologic findings of SCLE include hydropic degeneration of the basal cell layer and periadnexal infiltrates (Figure 5). The incidence of SCLE often is associated with anti-Ro (SSA) and anti-La (SSB) antibodies.15 Treatment of SCLE focuses on managing skin symptoms with corticosteroids, antimalarials, and sun protection.

- Bobosha K, Wilson L, van Meijgaarden KE, et al. T-cell regulation in lepromatous leprosy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:E2773. doi:10.1371 /journal.pntd.0002773

- Fischer M. Leprosy–an overview of clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2017;15:801-827. doi:10.1111/ddg.13301

- Jolly M, Pickard SA, Mikolaitis RA, et al. Lupus QoL-US benchmarks for US patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:1828-1833. doi:10.3899/jrheum.091443

- Chan MMF, Smoller BR. Overview of the histopathology and other laboratory investigations in leprosy. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2016;3:131-137. doi:10.1007/s40475-016-0086-y

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016; 75:457-465. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.03.054

- Lukács J, Schliemann S, Elsner P. Treatment of generalized granuloma annulare–a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1467-1480. doi:10.1111/jdv.12976

- Zinzani PL, Ferreri AJM, Cerroni L. Mycosis fungoides. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;65:172-182. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.08.004

- Ahn CS, ALSayyah A, Sangüeza OP. Mycosis fungoides: an updated review of clinicopathologic variants. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:933- 951. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000207

- Gutte R, Kharkar V, Mahajan S, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides with hypohidrosis mimicking lepromatous leprosy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:686. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.72470

- Kempf W, Ostheeren-Michaelis S, Paulli M, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin: a multicenter study of the cutaneous lymphoma histopathology task force group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1609-1617. doi:10.1001 /archdermatol.2008.46

- Miyashiro D, Cardona C, Valente N, et al. Ulcers in leprosy patients, an unrecognized clinical manifestation: a report of 8 cases. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:1013. doi:10.1186/s12879-019-4639-2

- Cerroni L. Mycosis fungoides-clinical and histopathologic features, differential diagnosis, and treatment. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2018;37:2-10. doi:10.12788/j.sder.2018.002

- Jain R, Yadav D, Puranik N, et al. Sarcoidosis: causes, diagnosis, clinical features, and treatments. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1081. doi:10.3390 /jcm9041081

- Zÿ ychowska M, Reich A. Dermoscopic features of acute, subacute, chronic and intermittent subtypes of cutaneous lupus erythematosus in Caucasians. J Clin Med. 2022;11:4088. doi:10.3390/jcm11144088

- Lazar AL. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: a facultative paraneoplastic dermatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:728-742. doi:10.1016 /j.clindermatol.2022.07.007

THE DIAGNOSIS: Lepromatous Leprosy

Histopathology showed collections of epithelioid to sarcoidal granulomas throughout the dermis and clustered around nerve bundles with a grenz zone at the dermoepidermal junction. Fite stain was positive for acid-fast bacteria, which were confirmed to be Mycobacterium leprae by by the National Hansen’s Disease program. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of lepromatous leprosy (LL) was made. The patient was treated by the infectious disease department with multidrug therapy that included monthly rifampin, moxifloxacin, and minocycline; weekly methotrexate with daily folic acid; and an extended prednisone taper with prophylactic cholecalciferol.

Lepromatous leprosy is characterized by high antibody titers to the acid-fast, gram-positive bacillus Mycobacterium leprae as well as a high bacillary load.1 Patients typically present with muscle weakness, anesthetic skin patches, and claw hands. Patients also may present with foot drop, ulcerations of the hands and feet, autonomic dysfunction with anhidrosis or impaired sweating, and localized alopecia.2 Over months to years, LL may progress to extensive sensory loss and indurated lesions that infiltrate the skin and cause thickening, especially on the face (known as leonine facies). Furthermore, LL is characterized by extensive bilaterally symmetric cutaneous lesions with poorly defined borders and raised indurated centers.3

Lepromatous leprosy transmission is not fully understood but is thought to occur via airborne droplets from coughing/sneezing and nasal secretions.2 Histopathology generally shows a dense and diffuse granulomatous infiltrate that involves the dermis but is separated from the epidermis by a zone of collagen (grenz zone).3 Histology is characterized by the presence of lymphocytes and numerous foamy macrophages (lepra or Virchow cells) containing M leprae organisms. In persistent lesions, the high density of uncleared bacilli forms spherical cytoplasmic clumps known as globi within enlarged foamy histiocytes (Figure 1).4 The macrophages form granulomatous lesions in the skin and around nerve bundles, resulting in tissue damage and decreased sensation. The current standard of care for LL is a multidrug combination of dapsone, rifampin, and clofazimine. Early diagnosis and complete treatment of LL is crucial, as this approach typically leads to complete cure of the disease.

The differential diagnosis for LL includes granuloma annulare (GA), mycosis fungoides (MF), sarcoidosis, and subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE). Granuloma annulare is a noninfectious inflammatory granulomatous skin disease that manifests in a localized, generalized, or subcutaneous pattern. Localized GA is the most common form and manifests as self-resolving, flesh-colored or erythematous papules or plaques limited to the extremities.5,6 Generalized GA is defined by more than 10 widespread annular plaques involving the trunk and extremities and can persist for decades.6 This form can be associated with hyperlipidemia, diabetes, autoimmune disease and immunodeficiency (eg, HIV), and rarely with lymphoma or solid tumors. On histology, GA shows necrobiosis surrounded by palisading histiocytes and mucin (palisading GA) or patchy interstitial histiocytes and lymphocytes (interstitial GA)(Figure 2).6 This palisading pattern differs from the histiocytes in LL, which contain numerous acid-fast bacilli and bacterial clumps. Topical and intralesional corticosteroids are first-line therapies for GA.

Mycosis fungoides is a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma characterized by proliferation of CD4+ T cells.7 In the early stages of MF, patients may present with multiple erythematous and scaly patches, plaques, or nodules that most commonly develop on unexposed areas of the skin, but specific variants frequently may cause lesions on the face or scalp.8 Tumors may be solitary, localized, or generalized and may be observed alongside patches and plaques or in the absence of cutaneous lesions.7 The pathologic features of MF include fibrosis of the papillary dermis, individual haloed atypical lymphocytes in the epidermis, and atypical lymphoid cells with cerebriform nuclei (Figure 3).9 Granulomatous MF is characterized by diffuse nodular and perivascular infiltrates of histiocytes with small lymphocytes without atypia, eosinophils, and plasma cells. Small lymphocytes with cerebriform nuclei and larger lymphocytes with hyperconvoluted nuclei also may be seen, in addition to multinucleated histiocytic giant cells. Although MF commonly manifests with epidermotropism, it typically is absent in granulomatous MF (GMF).10 Granulomatous MF may manifest similarly to LL. Noduloulcerative lesions and infiltration of atypical lymphocytes into the epidermis (epidermotropism) are much more common in GMF than in LL; however, although ulcerative nodules are not a common feature in patients with leprosy (except during reactional states [ie, Lucio phenomenon]) or secondary to neuropathies, they also can occur in LL.11 In GMF, the infiltrate does not follow a specific pattern, whereas LL infiltrates tend to follow a nerve distribution. Treatment for MF is determined by disease severity.12 First-line therapy includes local corticosteroids and phototherapy with UVB irradiation.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease that demonstrates nonspecific clinical manifestations affecting the lungs, eyes, liver, and skin.13 Environmental exposures to silica and inorganic matter have been linked to an increased risk for sarcoidosis, with patients presenting with fatigue, fever, and arthralgia.13 Skin manifestations include subcutaneous nodules, polymorphous plaques, and erythema nodosum—nodosum—the most common cutaneous presentation of sarcoidosis. Erythema nodosum manifests as symmetrically distributed, nonulcerative, painful red nodules on the skin, especially the lower legs. The histopathology of sarcoidosis shows noncaseating granulomas with activated T-lymphocytes, epithelioid cells, and multinucleated giant cells (Figure 4). Although granulomas occur in both LL and sarcoidosis, those in sarcoidosis typically consist of epithelioid cells surrounded by a rim of lymphocytes, whereas LL granulomas contain foamy histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. Treatment of sarcoidosis depends on disease progression and generally involves oral corticosteroids, followed by corticosteroid-sparing regimens.

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus is a chronic autoimmune disease that predominantly affects younger women. Common findings in SCLE include red scaly plaques and ring-shaped lesions on sun-exposed areas of the skin.14 Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus primarily is characterized by a photosensitive rash, often with arthralgia, myalgia, and/or oral ulcers; less commonly, a small percentage of patients can experience central nervous system involvement, vasculitis, or nephritis. The histologic findings of SCLE include hydropic degeneration of the basal cell layer and periadnexal infiltrates (Figure 5). The incidence of SCLE often is associated with anti-Ro (SSA) and anti-La (SSB) antibodies.15 Treatment of SCLE focuses on managing skin symptoms with corticosteroids, antimalarials, and sun protection.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Lepromatous Leprosy

Histopathology showed collections of epithelioid to sarcoidal granulomas throughout the dermis and clustered around nerve bundles with a grenz zone at the dermoepidermal junction. Fite stain was positive for acid-fast bacteria, which were confirmed to be Mycobacterium leprae by by the National Hansen’s Disease program. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of lepromatous leprosy (LL) was made. The patient was treated by the infectious disease department with multidrug therapy that included monthly rifampin, moxifloxacin, and minocycline; weekly methotrexate with daily folic acid; and an extended prednisone taper with prophylactic cholecalciferol.

Lepromatous leprosy is characterized by high antibody titers to the acid-fast, gram-positive bacillus Mycobacterium leprae as well as a high bacillary load.1 Patients typically present with muscle weakness, anesthetic skin patches, and claw hands. Patients also may present with foot drop, ulcerations of the hands and feet, autonomic dysfunction with anhidrosis or impaired sweating, and localized alopecia.2 Over months to years, LL may progress to extensive sensory loss and indurated lesions that infiltrate the skin and cause thickening, especially on the face (known as leonine facies). Furthermore, LL is characterized by extensive bilaterally symmetric cutaneous lesions with poorly defined borders and raised indurated centers.3

Lepromatous leprosy transmission is not fully understood but is thought to occur via airborne droplets from coughing/sneezing and nasal secretions.2 Histopathology generally shows a dense and diffuse granulomatous infiltrate that involves the dermis but is separated from the epidermis by a zone of collagen (grenz zone).3 Histology is characterized by the presence of lymphocytes and numerous foamy macrophages (lepra or Virchow cells) containing M leprae organisms. In persistent lesions, the high density of uncleared bacilli forms spherical cytoplasmic clumps known as globi within enlarged foamy histiocytes (Figure 1).4 The macrophages form granulomatous lesions in the skin and around nerve bundles, resulting in tissue damage and decreased sensation. The current standard of care for LL is a multidrug combination of dapsone, rifampin, and clofazimine. Early diagnosis and complete treatment of LL is crucial, as this approach typically leads to complete cure of the disease.

The differential diagnosis for LL includes granuloma annulare (GA), mycosis fungoides (MF), sarcoidosis, and subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE). Granuloma annulare is a noninfectious inflammatory granulomatous skin disease that manifests in a localized, generalized, or subcutaneous pattern. Localized GA is the most common form and manifests as self-resolving, flesh-colored or erythematous papules or plaques limited to the extremities.5,6 Generalized GA is defined by more than 10 widespread annular plaques involving the trunk and extremities and can persist for decades.6 This form can be associated with hyperlipidemia, diabetes, autoimmune disease and immunodeficiency (eg, HIV), and rarely with lymphoma or solid tumors. On histology, GA shows necrobiosis surrounded by palisading histiocytes and mucin (palisading GA) or patchy interstitial histiocytes and lymphocytes (interstitial GA)(Figure 2).6 This palisading pattern differs from the histiocytes in LL, which contain numerous acid-fast bacilli and bacterial clumps. Topical and intralesional corticosteroids are first-line therapies for GA.

Mycosis fungoides is a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma characterized by proliferation of CD4+ T cells.7 In the early stages of MF, patients may present with multiple erythematous and scaly patches, plaques, or nodules that most commonly develop on unexposed areas of the skin, but specific variants frequently may cause lesions on the face or scalp.8 Tumors may be solitary, localized, or generalized and may be observed alongside patches and plaques or in the absence of cutaneous lesions.7 The pathologic features of MF include fibrosis of the papillary dermis, individual haloed atypical lymphocytes in the epidermis, and atypical lymphoid cells with cerebriform nuclei (Figure 3).9 Granulomatous MF is characterized by diffuse nodular and perivascular infiltrates of histiocytes with small lymphocytes without atypia, eosinophils, and plasma cells. Small lymphocytes with cerebriform nuclei and larger lymphocytes with hyperconvoluted nuclei also may be seen, in addition to multinucleated histiocytic giant cells. Although MF commonly manifests with epidermotropism, it typically is absent in granulomatous MF (GMF).10 Granulomatous MF may manifest similarly to LL. Noduloulcerative lesions and infiltration of atypical lymphocytes into the epidermis (epidermotropism) are much more common in GMF than in LL; however, although ulcerative nodules are not a common feature in patients with leprosy (except during reactional states [ie, Lucio phenomenon]) or secondary to neuropathies, they also can occur in LL.11 In GMF, the infiltrate does not follow a specific pattern, whereas LL infiltrates tend to follow a nerve distribution. Treatment for MF is determined by disease severity.12 First-line therapy includes local corticosteroids and phototherapy with UVB irradiation.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease that demonstrates nonspecific clinical manifestations affecting the lungs, eyes, liver, and skin.13 Environmental exposures to silica and inorganic matter have been linked to an increased risk for sarcoidosis, with patients presenting with fatigue, fever, and arthralgia.13 Skin manifestations include subcutaneous nodules, polymorphous plaques, and erythema nodosum—nodosum—the most common cutaneous presentation of sarcoidosis. Erythema nodosum manifests as symmetrically distributed, nonulcerative, painful red nodules on the skin, especially the lower legs. The histopathology of sarcoidosis shows noncaseating granulomas with activated T-lymphocytes, epithelioid cells, and multinucleated giant cells (Figure 4). Although granulomas occur in both LL and sarcoidosis, those in sarcoidosis typically consist of epithelioid cells surrounded by a rim of lymphocytes, whereas LL granulomas contain foamy histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. Treatment of sarcoidosis depends on disease progression and generally involves oral corticosteroids, followed by corticosteroid-sparing regimens.

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus is a chronic autoimmune disease that predominantly affects younger women. Common findings in SCLE include red scaly plaques and ring-shaped lesions on sun-exposed areas of the skin.14 Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus primarily is characterized by a photosensitive rash, often with arthralgia, myalgia, and/or oral ulcers; less commonly, a small percentage of patients can experience central nervous system involvement, vasculitis, or nephritis. The histologic findings of SCLE include hydropic degeneration of the basal cell layer and periadnexal infiltrates (Figure 5). The incidence of SCLE often is associated with anti-Ro (SSA) and anti-La (SSB) antibodies.15 Treatment of SCLE focuses on managing skin symptoms with corticosteroids, antimalarials, and sun protection.

- Bobosha K, Wilson L, van Meijgaarden KE, et al. T-cell regulation in lepromatous leprosy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:E2773. doi:10.1371 /journal.pntd.0002773

- Fischer M. Leprosy–an overview of clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2017;15:801-827. doi:10.1111/ddg.13301

- Jolly M, Pickard SA, Mikolaitis RA, et al. Lupus QoL-US benchmarks for US patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:1828-1833. doi:10.3899/jrheum.091443

- Chan MMF, Smoller BR. Overview of the histopathology and other laboratory investigations in leprosy. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2016;3:131-137. doi:10.1007/s40475-016-0086-y

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016; 75:457-465. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.03.054

- Lukács J, Schliemann S, Elsner P. Treatment of generalized granuloma annulare–a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1467-1480. doi:10.1111/jdv.12976

- Zinzani PL, Ferreri AJM, Cerroni L. Mycosis fungoides. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;65:172-182. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.08.004

- Ahn CS, ALSayyah A, Sangüeza OP. Mycosis fungoides: an updated review of clinicopathologic variants. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:933- 951. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000207

- Gutte R, Kharkar V, Mahajan S, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides with hypohidrosis mimicking lepromatous leprosy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:686. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.72470

- Kempf W, Ostheeren-Michaelis S, Paulli M, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin: a multicenter study of the cutaneous lymphoma histopathology task force group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1609-1617. doi:10.1001 /archdermatol.2008.46

- Miyashiro D, Cardona C, Valente N, et al. Ulcers in leprosy patients, an unrecognized clinical manifestation: a report of 8 cases. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:1013. doi:10.1186/s12879-019-4639-2

- Cerroni L. Mycosis fungoides-clinical and histopathologic features, differential diagnosis, and treatment. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2018;37:2-10. doi:10.12788/j.sder.2018.002

- Jain R, Yadav D, Puranik N, et al. Sarcoidosis: causes, diagnosis, clinical features, and treatments. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1081. doi:10.3390 /jcm9041081

- Zÿ ychowska M, Reich A. Dermoscopic features of acute, subacute, chronic and intermittent subtypes of cutaneous lupus erythematosus in Caucasians. J Clin Med. 2022;11:4088. doi:10.3390/jcm11144088

- Lazar AL. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: a facultative paraneoplastic dermatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:728-742. doi:10.1016 /j.clindermatol.2022.07.007

- Bobosha K, Wilson L, van Meijgaarden KE, et al. T-cell regulation in lepromatous leprosy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:E2773. doi:10.1371 /journal.pntd.0002773

- Fischer M. Leprosy–an overview of clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2017;15:801-827. doi:10.1111/ddg.13301

- Jolly M, Pickard SA, Mikolaitis RA, et al. Lupus QoL-US benchmarks for US patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:1828-1833. doi:10.3899/jrheum.091443

- Chan MMF, Smoller BR. Overview of the histopathology and other laboratory investigations in leprosy. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2016;3:131-137. doi:10.1007/s40475-016-0086-y

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016; 75:457-465. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.03.054

- Lukács J, Schliemann S, Elsner P. Treatment of generalized granuloma annulare–a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1467-1480. doi:10.1111/jdv.12976

- Zinzani PL, Ferreri AJM, Cerroni L. Mycosis fungoides. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;65:172-182. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.08.004

- Ahn CS, ALSayyah A, Sangüeza OP. Mycosis fungoides: an updated review of clinicopathologic variants. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:933- 951. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000207

- Gutte R, Kharkar V, Mahajan S, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides with hypohidrosis mimicking lepromatous leprosy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:686. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.72470

- Kempf W, Ostheeren-Michaelis S, Paulli M, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin: a multicenter study of the cutaneous lymphoma histopathology task force group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1609-1617. doi:10.1001 /archdermatol.2008.46

- Miyashiro D, Cardona C, Valente N, et al. Ulcers in leprosy patients, an unrecognized clinical manifestation: a report of 8 cases. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:1013. doi:10.1186/s12879-019-4639-2

- Cerroni L. Mycosis fungoides-clinical and histopathologic features, differential diagnosis, and treatment. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2018;37:2-10. doi:10.12788/j.sder.2018.002

- Jain R, Yadav D, Puranik N, et al. Sarcoidosis: causes, diagnosis, clinical features, and treatments. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1081. doi:10.3390 /jcm9041081

- Zÿ ychowska M, Reich A. Dermoscopic features of acute, subacute, chronic and intermittent subtypes of cutaneous lupus erythematosus in Caucasians. J Clin Med. 2022;11:4088. doi:10.3390/jcm11144088

- Lazar AL. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: a facultative paraneoplastic dermatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:728-742. doi:10.1016 /j.clindermatol.2022.07.007

Smooth Symmetric Plaques on the Face, Trunk, and Extremities

Smooth Symmetric Plaques on the Face, Trunk, and Extremities

A 44-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with a widespread red, itchy, bumpy rash of 1 year’s duration. Physical examination revealed smooth, coalescing, erythematous and edematous plaques on the face (notably the forehead, malar cheeks, and nose), back, arms, and legs. Several plaques on the back had central hypopigmentation. The patient also reported numbness and weakness in the fingers and toes, and hypoesthesia within the lesions was noted. A biopsy of one of the lesions on the left ventral forearm was performed.

Nonhealing Friable Nodule on the Distal Edge of the Toe

Nonhealing Friable Nodule on the Distal Edge of the Toe

THE DIAGNOSIS: Squamoid Eccrine Ductal Carcinoma

Immunohistochemical staining of the biopsy specimen showed neoplastic aggregates that were diffusely positive for pancytokeratin and strongly positive for cytokeratin (CK) 5/6. Epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) and CK7 also were positive, CAM 5.2 was partially positive, and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) was focally positive (periluminal); S100 was negative. Given the histologic findings of irregular infiltrative cords and stranding exhibiting ductal differentiation in a fibrotic stroma in combination with the staining pattern, a diagnosis of squamous eccrine ductal carcinoma (SEDC) was made.

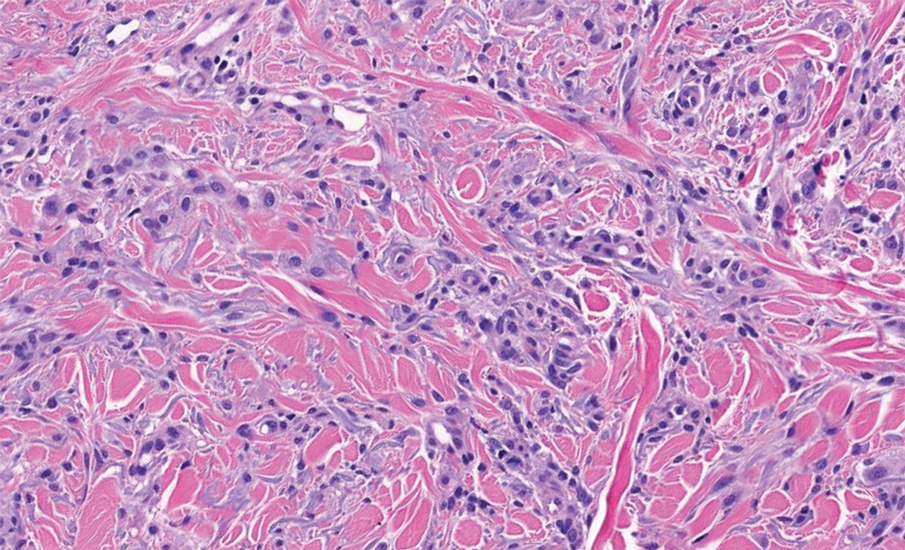

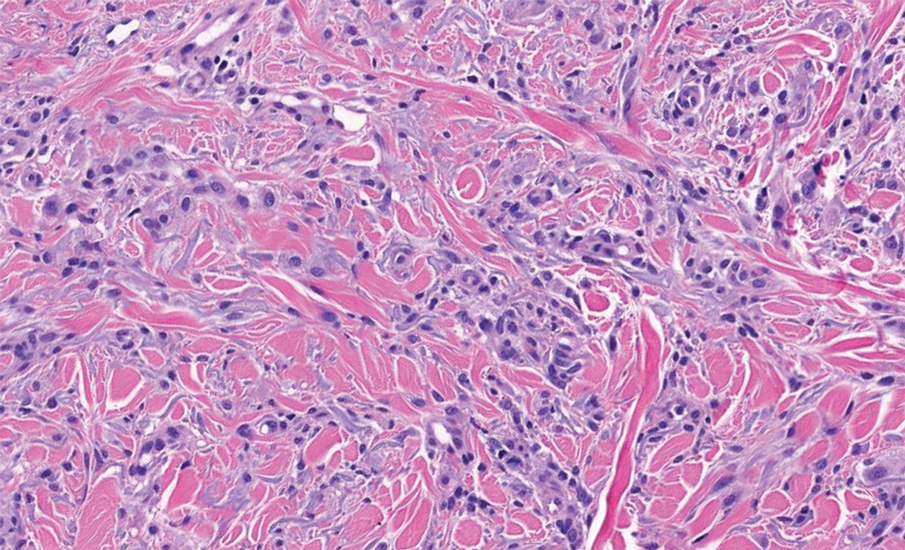

Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma is a rare primary cutaneous tumor with aggressive features that can be confused both clinically and histologically with squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Histologically, SEDC is a biphasic tumor. If a shallow histologic specimen is obtained, it may be indistinguishable from a well-differentiated SCC (Figure 1). A deeper biopsy reveals irregular infiltrative cords and strands exhibiting ductal differentiation in a fibrotic stroma.1

The immunohistochemical staining pattern of SEDC is similar to that of SCC, showing diffuse staining with pancytokeratin (AE1/AE3), CK 5/6, CK7, p63, and EMA. What distinguishes SEDC from SCC is that CEA highlights areas of glandular differentiation. An additional histologic feature seen commonly with SEDC is perineural invasion.

The etiology of SEDC remains controversial; although it originally was considered an aggressive variant of SCC along the same continuum as adenosquamous carcinoma, the fifth edition of the WHO Classification of Skin Tumors2 has categorized SEDC as an adnexal neoplasm. Our patient demonstrated an atypical presentation of this tumor, which has been most commonly described in the literature as manifesting on the head, neck, or upper extremities in older adults.3 Mohs micrographic surgery is the recommended treatment for this aggressive tumor.3

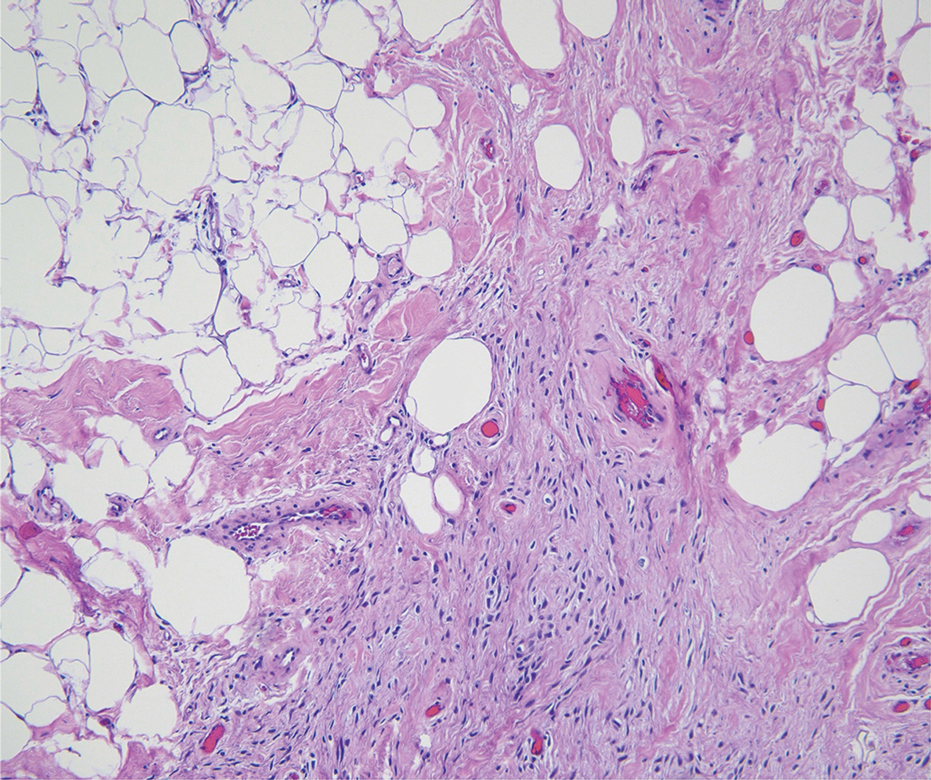

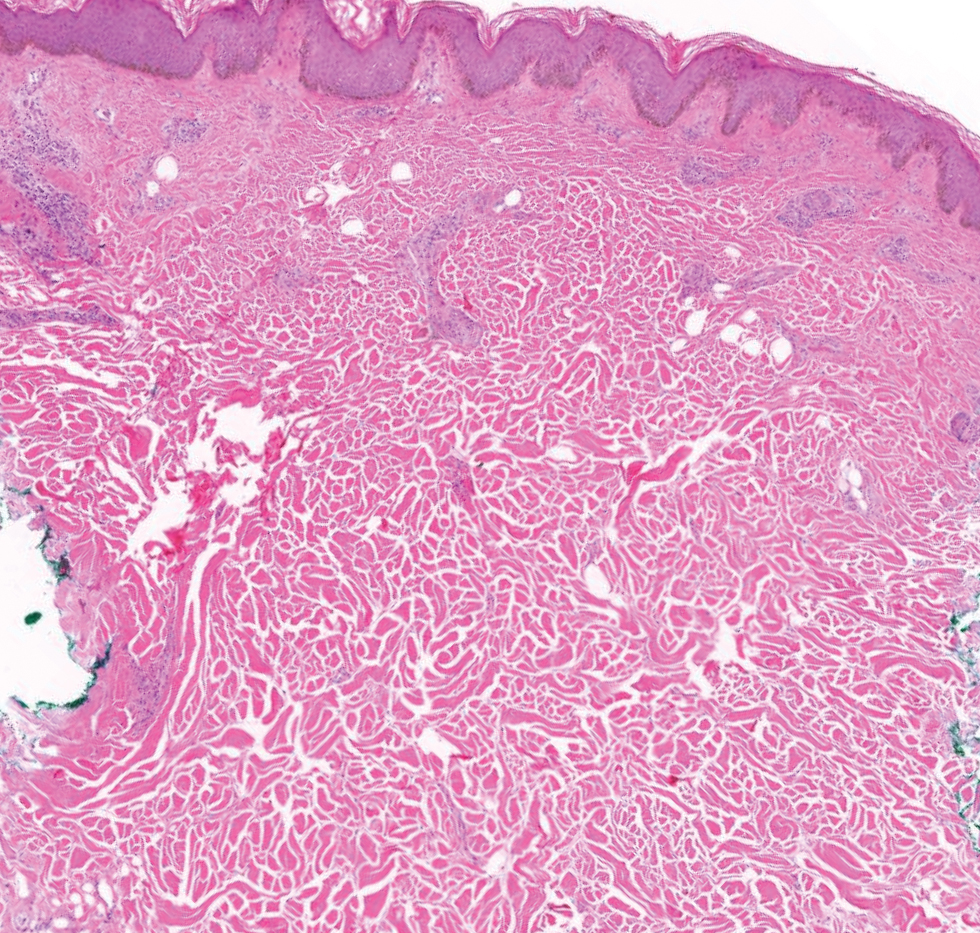

The differential diagnosis for SEDC includes microcystic adnexal carcinoma, porocarcinoma, and eccrine syringofibroadenoma. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma is a rare, low-grade tumor of the sweat glands that typically manifests as a firm pink papule or plaque in the head and neck region. Microscopically, it demonstrates cords of basaloid cells in a paisley-tie tadpole pattern with a dense pink to red stroma and horn cysts (Figure 2). Histologic differential diagnoses include syringoma, morpheaform basal cell carcinoma, desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, and trichoadenoma. Carcinoembryonic antigen stains positive in microcystic adnexal carcinoma, which helps distinguish it from basal cell carcinoma and SCC. Surgical excision or Mohs surgery are recommended for management.4

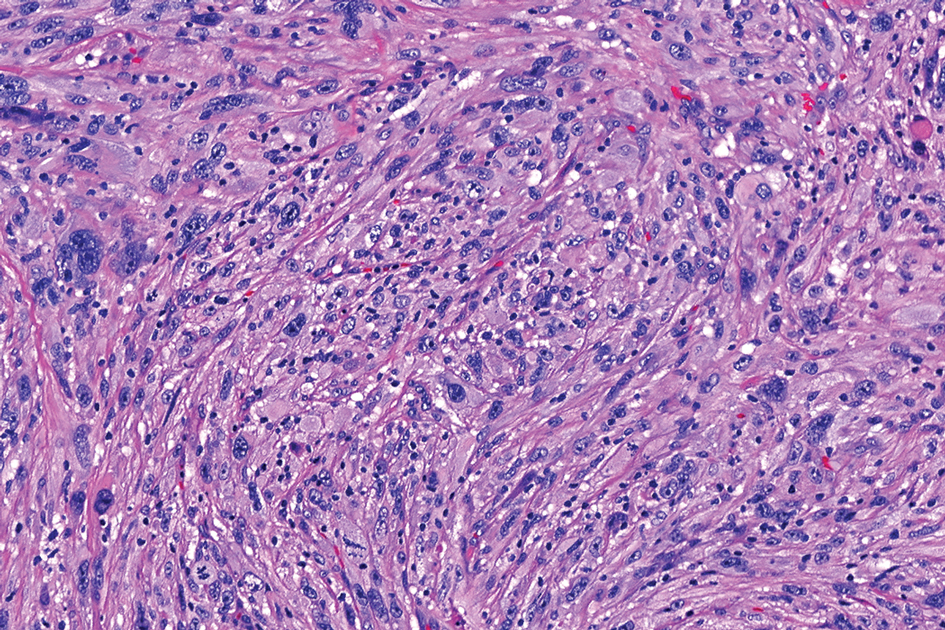

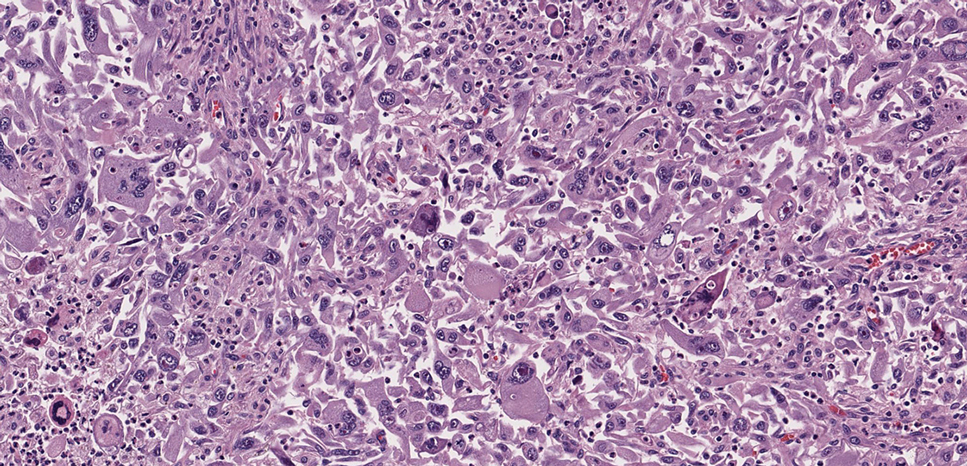

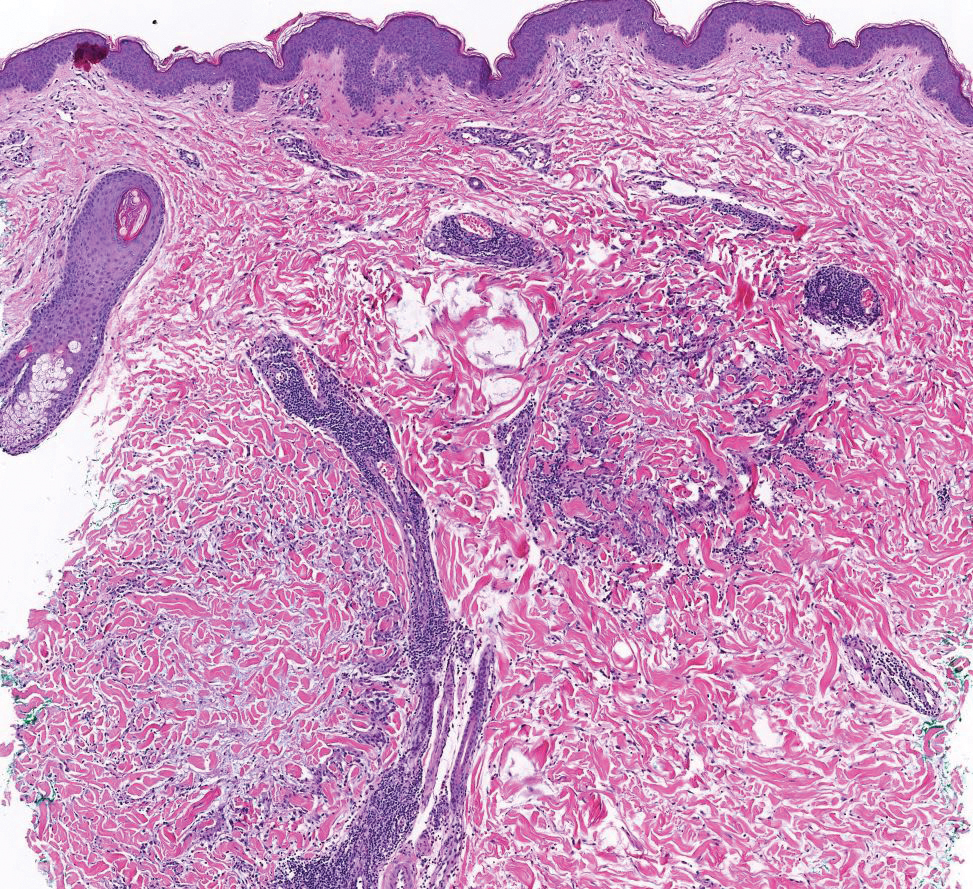

Porocarcinoma is a malignant skin tumor that originates from the intraepidermal sweat gland ducts. It also has been proposed that porocarcinoma develops from benign eccrine poroma. Porocarcinoma often is seen in elderly individuals, with a predilection for the lower extremities. Porocarcinoma demonstrates diverse clinical and histopathologic features, which can make diagnosis challenging. Histopathologically, porocarcinoma has an infiltrative growth pattern, with large basaloid epithelial cells that demonstrate ductal differentiation, cytologic atypia, increased mitotic activity, and tumor necrosis (Figure 3). Some porocarcinomas may exhibit squamous-cell, spindle-cell, or clear-cell differentiation. Neoplastic cells stain positive for CEA, EMA, and CD117, which can assist in distinguishing porocarcinoma from cutaneous SCC.5

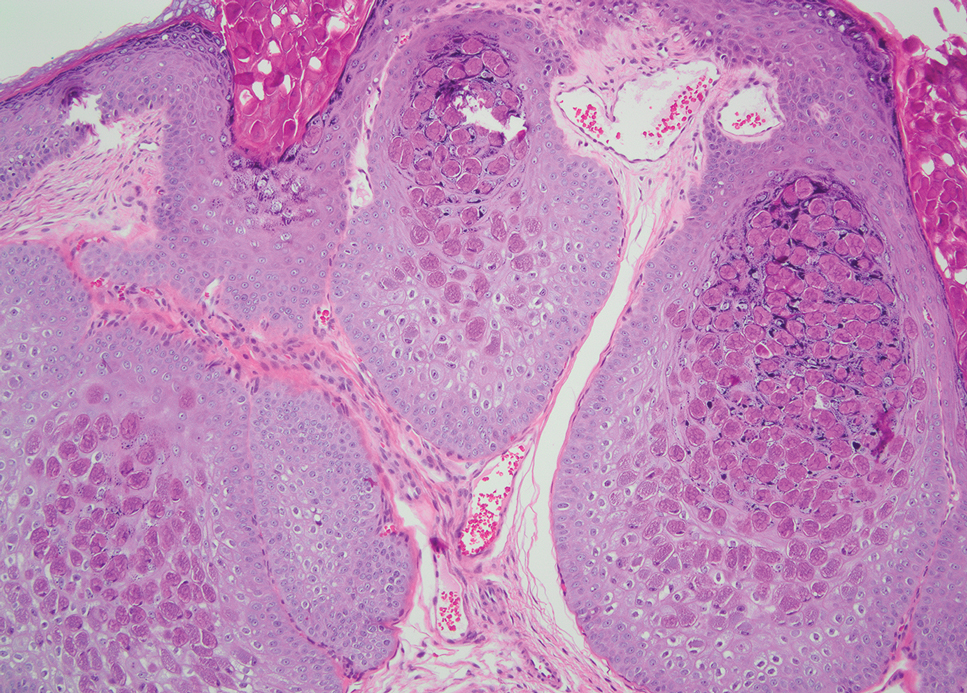

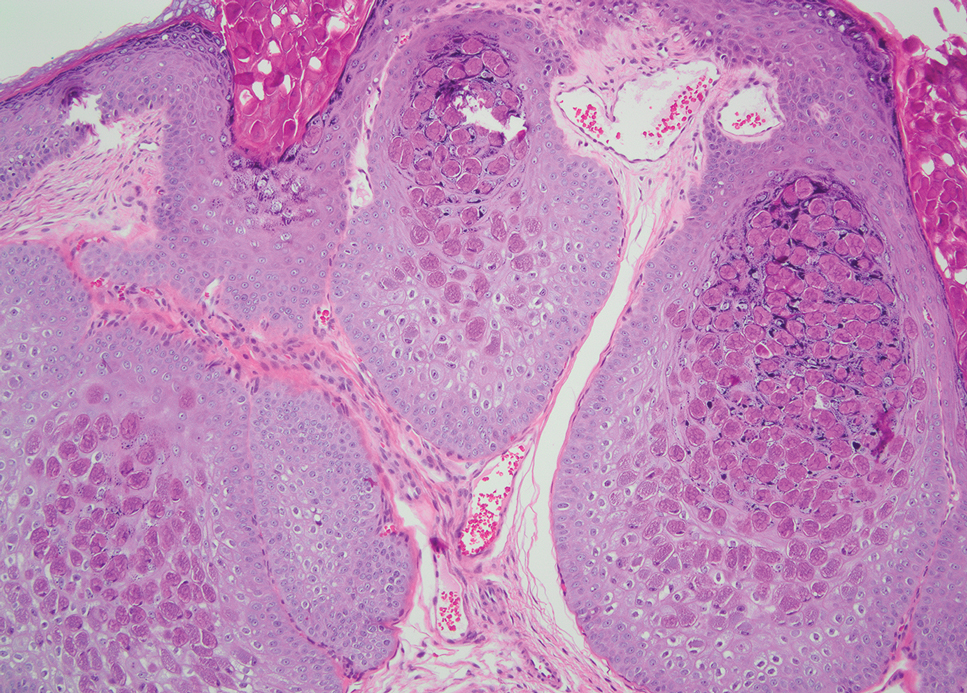

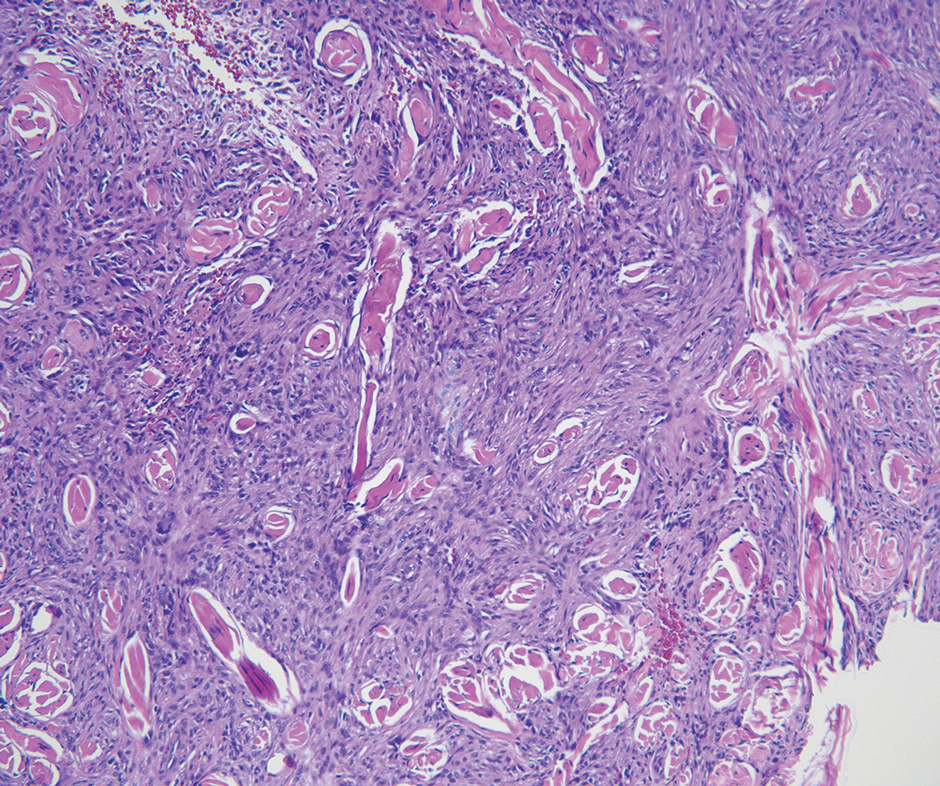

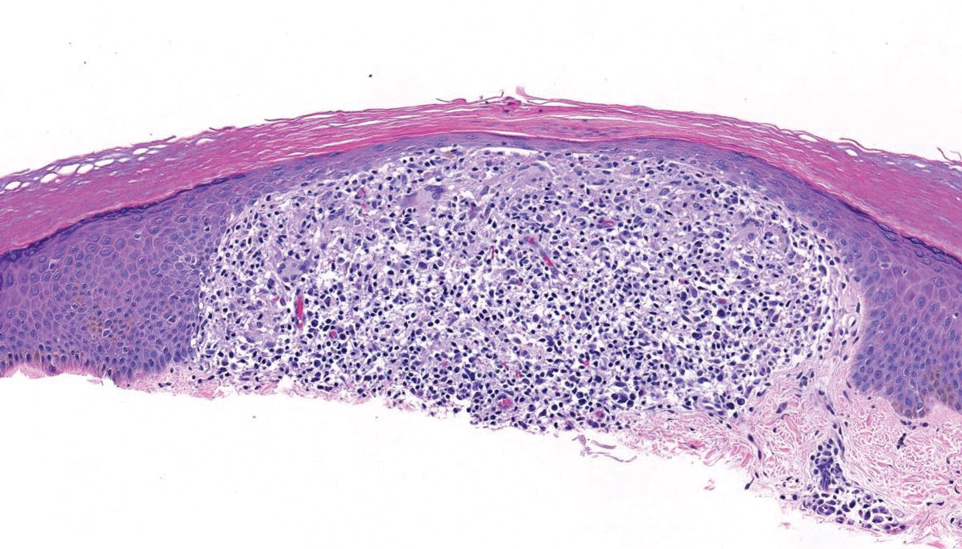

Eccrine syringofibroadenoma is an unusual benign cutaneous adnexal tumor that manifests mostly in individuals aged 40 years or older. It develops as single or multiple lesions that usually affect the lower extremities. Histologically, eccrine syringofibroadenoma demonstrates unique findings of anastomosing ducts and monomorphous epithelial cells within a fibrovascular stroma (Figure 4). On immunohistochemistry, it stains positive for EMA, CEA, high-molecular-weight kininogen, and filaggrin.6 Periodic acid–Schiff staining also is positive.

- Svoboda SA, Rush PS, Garofola CJ, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma. Cutis. 2021;107:E5-E9. doi:10.12788/cutis.0280

- WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Skin tumours. 5th ed. Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2023.

- van der Horst MP, Garcia-Herrera A, Markiewicz D, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study of 30 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:755-760. doi:10.1097/PAS.0000000000000599

- Zito PM, Mazzoni T. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Updated April 24, 2023. Accessed August 3, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557857/

- Tsiogka A, Koumaki D, Kyriazopoulou M, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma: a review of the literature. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13:8. doi:10.3390/diagnostics13081431

- Ko EJ, Park KY, Kwon HJ, et al. Eccrine syringofibroadenoma in a patient with long-standing exfoliative dermatitis. Ann Dermatol. 2016;28:765-768. doi:10.5021/ad.2016.28.6.765

THE DIAGNOSIS: Squamoid Eccrine Ductal Carcinoma

Immunohistochemical staining of the biopsy specimen showed neoplastic aggregates that were diffusely positive for pancytokeratin and strongly positive for cytokeratin (CK) 5/6. Epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) and CK7 also were positive, CAM 5.2 was partially positive, and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) was focally positive (periluminal); S100 was negative. Given the histologic findings of irregular infiltrative cords and stranding exhibiting ductal differentiation in a fibrotic stroma in combination with the staining pattern, a diagnosis of squamous eccrine ductal carcinoma (SEDC) was made.

Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma is a rare primary cutaneous tumor with aggressive features that can be confused both clinically and histologically with squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Histologically, SEDC is a biphasic tumor. If a shallow histologic specimen is obtained, it may be indistinguishable from a well-differentiated SCC (Figure 1). A deeper biopsy reveals irregular infiltrative cords and strands exhibiting ductal differentiation in a fibrotic stroma.1

The immunohistochemical staining pattern of SEDC is similar to that of SCC, showing diffuse staining with pancytokeratin (AE1/AE3), CK 5/6, CK7, p63, and EMA. What distinguishes SEDC from SCC is that CEA highlights areas of glandular differentiation. An additional histologic feature seen commonly with SEDC is perineural invasion.

The etiology of SEDC remains controversial; although it originally was considered an aggressive variant of SCC along the same continuum as adenosquamous carcinoma, the fifth edition of the WHO Classification of Skin Tumors2 has categorized SEDC as an adnexal neoplasm. Our patient demonstrated an atypical presentation of this tumor, which has been most commonly described in the literature as manifesting on the head, neck, or upper extremities in older adults.3 Mohs micrographic surgery is the recommended treatment for this aggressive tumor.3

The differential diagnosis for SEDC includes microcystic adnexal carcinoma, porocarcinoma, and eccrine syringofibroadenoma. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma is a rare, low-grade tumor of the sweat glands that typically manifests as a firm pink papule or plaque in the head and neck region. Microscopically, it demonstrates cords of basaloid cells in a paisley-tie tadpole pattern with a dense pink to red stroma and horn cysts (Figure 2). Histologic differential diagnoses include syringoma, morpheaform basal cell carcinoma, desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, and trichoadenoma. Carcinoembryonic antigen stains positive in microcystic adnexal carcinoma, which helps distinguish it from basal cell carcinoma and SCC. Surgical excision or Mohs surgery are recommended for management.4

Porocarcinoma is a malignant skin tumor that originates from the intraepidermal sweat gland ducts. It also has been proposed that porocarcinoma develops from benign eccrine poroma. Porocarcinoma often is seen in elderly individuals, with a predilection for the lower extremities. Porocarcinoma demonstrates diverse clinical and histopathologic features, which can make diagnosis challenging. Histopathologically, porocarcinoma has an infiltrative growth pattern, with large basaloid epithelial cells that demonstrate ductal differentiation, cytologic atypia, increased mitotic activity, and tumor necrosis (Figure 3). Some porocarcinomas may exhibit squamous-cell, spindle-cell, or clear-cell differentiation. Neoplastic cells stain positive for CEA, EMA, and CD117, which can assist in distinguishing porocarcinoma from cutaneous SCC.5

Eccrine syringofibroadenoma is an unusual benign cutaneous adnexal tumor that manifests mostly in individuals aged 40 years or older. It develops as single or multiple lesions that usually affect the lower extremities. Histologically, eccrine syringofibroadenoma demonstrates unique findings of anastomosing ducts and monomorphous epithelial cells within a fibrovascular stroma (Figure 4). On immunohistochemistry, it stains positive for EMA, CEA, high-molecular-weight kininogen, and filaggrin.6 Periodic acid–Schiff staining also is positive.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Squamoid Eccrine Ductal Carcinoma

Immunohistochemical staining of the biopsy specimen showed neoplastic aggregates that were diffusely positive for pancytokeratin and strongly positive for cytokeratin (CK) 5/6. Epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) and CK7 also were positive, CAM 5.2 was partially positive, and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) was focally positive (periluminal); S100 was negative. Given the histologic findings of irregular infiltrative cords and stranding exhibiting ductal differentiation in a fibrotic stroma in combination with the staining pattern, a diagnosis of squamous eccrine ductal carcinoma (SEDC) was made.

Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma is a rare primary cutaneous tumor with aggressive features that can be confused both clinically and histologically with squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Histologically, SEDC is a biphasic tumor. If a shallow histologic specimen is obtained, it may be indistinguishable from a well-differentiated SCC (Figure 1). A deeper biopsy reveals irregular infiltrative cords and strands exhibiting ductal differentiation in a fibrotic stroma.1

The immunohistochemical staining pattern of SEDC is similar to that of SCC, showing diffuse staining with pancytokeratin (AE1/AE3), CK 5/6, CK7, p63, and EMA. What distinguishes SEDC from SCC is that CEA highlights areas of glandular differentiation. An additional histologic feature seen commonly with SEDC is perineural invasion.

The etiology of SEDC remains controversial; although it originally was considered an aggressive variant of SCC along the same continuum as adenosquamous carcinoma, the fifth edition of the WHO Classification of Skin Tumors2 has categorized SEDC as an adnexal neoplasm. Our patient demonstrated an atypical presentation of this tumor, which has been most commonly described in the literature as manifesting on the head, neck, or upper extremities in older adults.3 Mohs micrographic surgery is the recommended treatment for this aggressive tumor.3

The differential diagnosis for SEDC includes microcystic adnexal carcinoma, porocarcinoma, and eccrine syringofibroadenoma. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma is a rare, low-grade tumor of the sweat glands that typically manifests as a firm pink papule or plaque in the head and neck region. Microscopically, it demonstrates cords of basaloid cells in a paisley-tie tadpole pattern with a dense pink to red stroma and horn cysts (Figure 2). Histologic differential diagnoses include syringoma, morpheaform basal cell carcinoma, desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, and trichoadenoma. Carcinoembryonic antigen stains positive in microcystic adnexal carcinoma, which helps distinguish it from basal cell carcinoma and SCC. Surgical excision or Mohs surgery are recommended for management.4

Porocarcinoma is a malignant skin tumor that originates from the intraepidermal sweat gland ducts. It also has been proposed that porocarcinoma develops from benign eccrine poroma. Porocarcinoma often is seen in elderly individuals, with a predilection for the lower extremities. Porocarcinoma demonstrates diverse clinical and histopathologic features, which can make diagnosis challenging. Histopathologically, porocarcinoma has an infiltrative growth pattern, with large basaloid epithelial cells that demonstrate ductal differentiation, cytologic atypia, increased mitotic activity, and tumor necrosis (Figure 3). Some porocarcinomas may exhibit squamous-cell, spindle-cell, or clear-cell differentiation. Neoplastic cells stain positive for CEA, EMA, and CD117, which can assist in distinguishing porocarcinoma from cutaneous SCC.5

Eccrine syringofibroadenoma is an unusual benign cutaneous adnexal tumor that manifests mostly in individuals aged 40 years or older. It develops as single or multiple lesions that usually affect the lower extremities. Histologically, eccrine syringofibroadenoma demonstrates unique findings of anastomosing ducts and monomorphous epithelial cells within a fibrovascular stroma (Figure 4). On immunohistochemistry, it stains positive for EMA, CEA, high-molecular-weight kininogen, and filaggrin.6 Periodic acid–Schiff staining also is positive.

- Svoboda SA, Rush PS, Garofola CJ, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma. Cutis. 2021;107:E5-E9. doi:10.12788/cutis.0280

- WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Skin tumours. 5th ed. Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2023.

- van der Horst MP, Garcia-Herrera A, Markiewicz D, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study of 30 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:755-760. doi:10.1097/PAS.0000000000000599

- Zito PM, Mazzoni T. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Updated April 24, 2023. Accessed August 3, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557857/

- Tsiogka A, Koumaki D, Kyriazopoulou M, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma: a review of the literature. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13:8. doi:10.3390/diagnostics13081431

- Ko EJ, Park KY, Kwon HJ, et al. Eccrine syringofibroadenoma in a patient with long-standing exfoliative dermatitis. Ann Dermatol. 2016;28:765-768. doi:10.5021/ad.2016.28.6.765

- Svoboda SA, Rush PS, Garofola CJ, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma. Cutis. 2021;107:E5-E9. doi:10.12788/cutis.0280

- WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Skin tumours. 5th ed. Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2023.

- van der Horst MP, Garcia-Herrera A, Markiewicz D, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study of 30 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:755-760. doi:10.1097/PAS.0000000000000599

- Zito PM, Mazzoni T. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Updated April 24, 2023. Accessed August 3, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557857/

- Tsiogka A, Koumaki D, Kyriazopoulou M, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma: a review of the literature. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13:8. doi:10.3390/diagnostics13081431

- Ko EJ, Park KY, Kwon HJ, et al. Eccrine syringofibroadenoma in a patient with long-standing exfoliative dermatitis. Ann Dermatol. 2016;28:765-768. doi:10.5021/ad.2016.28.6.765

Nonhealing Friable Nodule on the Distal Edge of the Toe

Nonhealing Friable Nodule on the Distal Edge of the Toe

A 37-year-old woman with no notable medical history presented to the dermatology clinic with a nonhealing wound on the left fifth toe of 10 month’s duration. The patient reported that the wound developed after burning the toe on an indoor space heater. Physical examination revealed a friable pink papule with a hemorrhagic crust. A biopsy of the lesion was performed.

Scattered Umbilicated Papules on the Cheek, Neck, and Arms

Scattered Umbilicated Papules on the Cheek, Neck, and Arms

THE DIAGNOSIS: Mpox Virus

The histopathologic features of mpox virus infection may vary depending on the stage of evolution; findings include ballooning degeneration with multinucleated keratinocytes, acanthosis, spongiosis, a neutrophil-rich inflammatory infiltrate, and eosinophilic intracytoplasmic (Guarnieri) inclusion bodies (quiz image inset [arrows]). Prominent neutrophil exocytosis also has been described and may be a characteristic feature in the pustular stage.1,2 A pattern of interface dermatitis also has been observed on histopathology.3 In our patient, the diagnosis of mpox initially was made by clinical and histopathologic correlation and exclusion of other entities in the differential diagnosis. The diagnosis subsequently was confirmed by real-time polymerase chain reaction. The patient received treatment with tecovirimat, but lesions progressed over the following 6 weeks. He subsequently died due to sepsis and multiorgan failure secondary to AIDS.

Mpox is a zoonotic, double-stranded DNA virus of the genus Orthopoxvirus in the family Poxviridae.4 It is transmitted to humans via direct contact with infected animals, most commonly small mammals such as monkeys, squirrels, and rodents. Mpox also may be transmitted between humans through direct contact with bodily fluids, skin and mucosal lesions, respiratory droplets, or fomites. Mpox infection typically begins with a nonspecific flulike prodrome after a 5- to 21-day incubation period, followed by skin lesions of variable morphology affecting any region of the body. Clinically, mpox lesions have been reported to evolve through macular, papular, and vesiculopustular phases, followed by resolution with crusting. Lesions may occur anywhere on the body but frequently manifest on the face then spread centrifugally across the body, with various phases observed simultaneously.5 A worldwide outbreak in 2022 involved larger numbers of cases in nonendemic areas, primarily due to skin-to-skin contact, with predominant anal and genital localization of the lesions as well as fewer prodromal symptoms.6

The differential diagnosis of crusted and umbilicated papules includes disseminated herpesvirus infection, molluscum contagiosum, disseminated cryptococcosis, and histoplasmosis. Additional causative organisms to consider include Penicillium, Mycobacterium tuberculosis and nontuberculous mycobacteria, as well as Sporothrix schenckii.

Herpesvirus infections may have similar clinical and histopathologic findings to mpox. Histopathologically, herpes simplex virus (HSV) and varicella zoster virus (VZV) are essentially identical; both demonstrate ballooning and reticular epidermal degeneration, chromatin condensation, nuclear degeneration, multinucleated keratinocytes with steel-gray nuclei, and prominent epidermal acantholysis with an inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 1). However, involvement of folliculosebaceous units may favor a diagnosis of VZV. Immunohistochemical staining can further differentiate between HSV and VZV.7 While mpox may have features that overlap with both HSV and VZV, including ballooning degeneration and multinucleated keratinocytes with nuclear degeneration, acantholysis is a less commonly reported feature of mpox, and mpox virus infection is characterized by intracytoplasmic (Guarnieri) inclusion bodies rather than the intranuclear inclusion bodies of HSV and VZV.2,5 The presence of Guarnieri bodies in mpox may further help to distinguish mpox from HSV infection on routine histology.

Molluscum contagiosum infection typically manifests as multiple umbilicated papules at sites of inoculation. Large lesions may be seen in the setting of immunosuppression; however, they usually do not progress to vesicular, pustular, or crusted morphologies. Histopathology demonstrates a cup-shaped invagination of the epidermis into the dermis and proliferative rete ridges that descend downward and encircle the dermis with large eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion (Henderson-Patterson) bodies (Figure 2).8

Disseminated cryptococcus infection is caused by the invasive fungus Cryptococcus neoformans and is characterized by meningitis along with fever, malaise, headache, neck stiffness, photophobia, nausea, vomiting, pneumonia with cough and dyspnea, and skin rash, most commonly in immunocompromised individuals.9 Skin lesions are a sign of disseminated infection and can manifest as umbilicated or molluscumlike lesions. Histopathology of cryptococcosis demonstrates a granulomatous dermal infiltrate with neutrophils and pleomorphic yeasts measuring 4 µm to 6 µm with refringent capsules.10 Staining with Grocott methenamine silver and/or mucicarmine for yeast capsules can help to identify organisms (Figure 3).

Cutaneous histoplasmosis is caused by Histoplasma capsulatum, a dimorphic fungus that can lead to pulmonary, cutaneous, and disseminated disease, often in immunocompromised patients.11 Cutaneous disease may manifest with molluscumlike or verrucous papules and plaques. Histopathologic examination reveals diffuse suppurative and granulomatous infiltrates with foamy histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells, containing intracellular and extracellular yeasts measuring 1µm to 5µm, surrounded by a clear halo visible with Grocott methenamine silver stain (Figure 4).

×600). Grocott methenamine silver staining highlights numerous intracellular yeasts (inset, original magnification ×600).

Spreading cutaneous lesions in an immunocompromised individual may be the presentation of multiple infectious etiologies. With the recent rise in mpox cases occurring in nonendemic areas, clinicians should be aware of the spectrum of clinical findings that may occur. Notably, more than one infection may be present in severely immunocompromised individuals, as seen in our patient with chronic orolabial HSV-2 and acute mpox infection. Thorough clinical, histopathologic, and laboratory investigations are necessary for timely diagnosis, appropriate treatment, and exclusion of other life-threatening conditions.

- Moltrasio C, Boggio FL, Romagnuolo M, et al. Monkeypox: a histopathological and transmission electron microscopy study. Microorganisms. 2023;11:1781-1793. doi:10.3390/microorganisms11071781

- Ortins-Pina A, Hegemann B, Saggini A, et al. Histopathological features of human mpox: report of two cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2023;50:706-710. doi:10.1111/cup.14398

- Chalali F, Merlant M, Truong A, et al. Histological features associated with human mpox virus infection in 2022 outbreak in a nonendemic country. Clin Infect Dis. 21;76:1132-1135. doi:10.1093/cid/ciac856.

- Mpox (monkeypox). World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/health-topics/monkeypox/#tab=tab_1. Accessed August 6, 2025.

- Petersen E, Kantele A, Koopmans M, et al. Human monkeypox: epidemiologic and clinical characteristics, diagnosis, and prevention. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2019;33:1027-1043. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2019.03.001

- Philpott D, Hughes CM, Alroy KA, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of monkeypox cases — United States, May 17–July 22, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:1018-1022. doi:10.15585 /mmwr.mm7132e3

- Nikkels AF, Debrus S, Sadzot-Delvaux C, et al. Comparative immunohistochemical study of herpes simplex and varicella-zoster infections. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1993;422:121-126. doi:10.1007 /BF01607163

- Badri T, Gandhi GR. Molluscum Contagiosum. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Updated March 27, 2023. Accessed August 8, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441898/

- Mada PK, Jamil RT, Alam MU. Cryptococcus. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Updated August 7, 2023. Accessed August 8, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431060/

- Hayashida MZ, Seque CA, Pasin VP, et al. Disseminated cryptococcosis with skin lesions: report of a case series. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:69-72. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20176343

- Mustari AP, Rao S, Keshavamurthy V, et al. Dermoscopic evaluation of cutaneous histoplasmosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2023;19:1-4. doi:10.25259/IJDVL_889_2022

THE DIAGNOSIS: Mpox Virus

The histopathologic features of mpox virus infection may vary depending on the stage of evolution; findings include ballooning degeneration with multinucleated keratinocytes, acanthosis, spongiosis, a neutrophil-rich inflammatory infiltrate, and eosinophilic intracytoplasmic (Guarnieri) inclusion bodies (quiz image inset [arrows]). Prominent neutrophil exocytosis also has been described and may be a characteristic feature in the pustular stage.1,2 A pattern of interface dermatitis also has been observed on histopathology.3 In our patient, the diagnosis of mpox initially was made by clinical and histopathologic correlation and exclusion of other entities in the differential diagnosis. The diagnosis subsequently was confirmed by real-time polymerase chain reaction. The patient received treatment with tecovirimat, but lesions progressed over the following 6 weeks. He subsequently died due to sepsis and multiorgan failure secondary to AIDS.

Mpox is a zoonotic, double-stranded DNA virus of the genus Orthopoxvirus in the family Poxviridae.4 It is transmitted to humans via direct contact with infected animals, most commonly small mammals such as monkeys, squirrels, and rodents. Mpox also may be transmitted between humans through direct contact with bodily fluids, skin and mucosal lesions, respiratory droplets, or fomites. Mpox infection typically begins with a nonspecific flulike prodrome after a 5- to 21-day incubation period, followed by skin lesions of variable morphology affecting any region of the body. Clinically, mpox lesions have been reported to evolve through macular, papular, and vesiculopustular phases, followed by resolution with crusting. Lesions may occur anywhere on the body but frequently manifest on the face then spread centrifugally across the body, with various phases observed simultaneously.5 A worldwide outbreak in 2022 involved larger numbers of cases in nonendemic areas, primarily due to skin-to-skin contact, with predominant anal and genital localization of the lesions as well as fewer prodromal symptoms.6

The differential diagnosis of crusted and umbilicated papules includes disseminated herpesvirus infection, molluscum contagiosum, disseminated cryptococcosis, and histoplasmosis. Additional causative organisms to consider include Penicillium, Mycobacterium tuberculosis and nontuberculous mycobacteria, as well as Sporothrix schenckii.

Herpesvirus infections may have similar clinical and histopathologic findings to mpox. Histopathologically, herpes simplex virus (HSV) and varicella zoster virus (VZV) are essentially identical; both demonstrate ballooning and reticular epidermal degeneration, chromatin condensation, nuclear degeneration, multinucleated keratinocytes with steel-gray nuclei, and prominent epidermal acantholysis with an inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 1). However, involvement of folliculosebaceous units may favor a diagnosis of VZV. Immunohistochemical staining can further differentiate between HSV and VZV.7 While mpox may have features that overlap with both HSV and VZV, including ballooning degeneration and multinucleated keratinocytes with nuclear degeneration, acantholysis is a less commonly reported feature of mpox, and mpox virus infection is characterized by intracytoplasmic (Guarnieri) inclusion bodies rather than the intranuclear inclusion bodies of HSV and VZV.2,5 The presence of Guarnieri bodies in mpox may further help to distinguish mpox from HSV infection on routine histology.

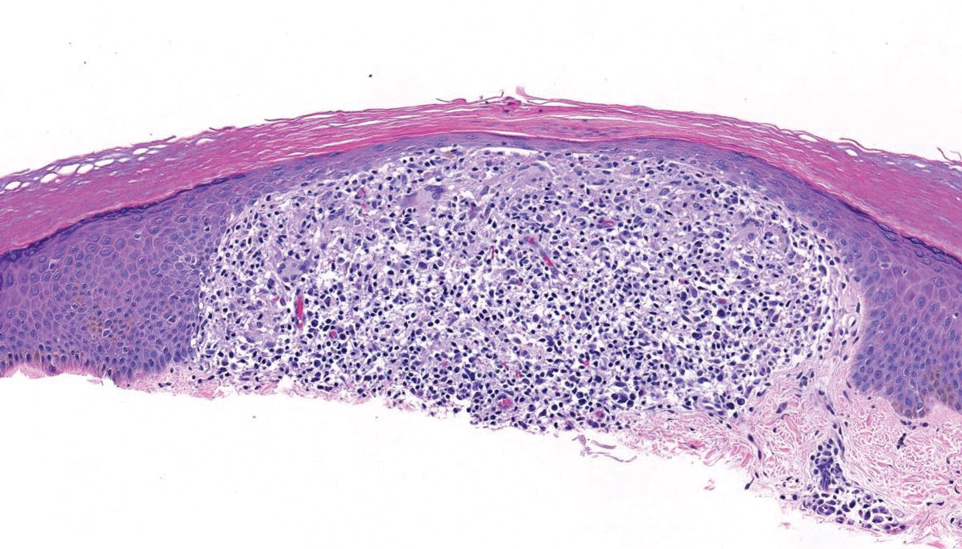

Molluscum contagiosum infection typically manifests as multiple umbilicated papules at sites of inoculation. Large lesions may be seen in the setting of immunosuppression; however, they usually do not progress to vesicular, pustular, or crusted morphologies. Histopathology demonstrates a cup-shaped invagination of the epidermis into the dermis and proliferative rete ridges that descend downward and encircle the dermis with large eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion (Henderson-Patterson) bodies (Figure 2).8

Disseminated cryptococcus infection is caused by the invasive fungus Cryptococcus neoformans and is characterized by meningitis along with fever, malaise, headache, neck stiffness, photophobia, nausea, vomiting, pneumonia with cough and dyspnea, and skin rash, most commonly in immunocompromised individuals.9 Skin lesions are a sign of disseminated infection and can manifest as umbilicated or molluscumlike lesions. Histopathology of cryptococcosis demonstrates a granulomatous dermal infiltrate with neutrophils and pleomorphic yeasts measuring 4 µm to 6 µm with refringent capsules.10 Staining with Grocott methenamine silver and/or mucicarmine for yeast capsules can help to identify organisms (Figure 3).

Cutaneous histoplasmosis is caused by Histoplasma capsulatum, a dimorphic fungus that can lead to pulmonary, cutaneous, and disseminated disease, often in immunocompromised patients.11 Cutaneous disease may manifest with molluscumlike or verrucous papules and plaques. Histopathologic examination reveals diffuse suppurative and granulomatous infiltrates with foamy histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells, containing intracellular and extracellular yeasts measuring 1µm to 5µm, surrounded by a clear halo visible with Grocott methenamine silver stain (Figure 4).

×600). Grocott methenamine silver staining highlights numerous intracellular yeasts (inset, original magnification ×600).

Spreading cutaneous lesions in an immunocompromised individual may be the presentation of multiple infectious etiologies. With the recent rise in mpox cases occurring in nonendemic areas, clinicians should be aware of the spectrum of clinical findings that may occur. Notably, more than one infection may be present in severely immunocompromised individuals, as seen in our patient with chronic orolabial HSV-2 and acute mpox infection. Thorough clinical, histopathologic, and laboratory investigations are necessary for timely diagnosis, appropriate treatment, and exclusion of other life-threatening conditions.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Mpox Virus

The histopathologic features of mpox virus infection may vary depending on the stage of evolution; findings include ballooning degeneration with multinucleated keratinocytes, acanthosis, spongiosis, a neutrophil-rich inflammatory infiltrate, and eosinophilic intracytoplasmic (Guarnieri) inclusion bodies (quiz image inset [arrows]). Prominent neutrophil exocytosis also has been described and may be a characteristic feature in the pustular stage.1,2 A pattern of interface dermatitis also has been observed on histopathology.3 In our patient, the diagnosis of mpox initially was made by clinical and histopathologic correlation and exclusion of other entities in the differential diagnosis. The diagnosis subsequently was confirmed by real-time polymerase chain reaction. The patient received treatment with tecovirimat, but lesions progressed over the following 6 weeks. He subsequently died due to sepsis and multiorgan failure secondary to AIDS.

Mpox is a zoonotic, double-stranded DNA virus of the genus Orthopoxvirus in the family Poxviridae.4 It is transmitted to humans via direct contact with infected animals, most commonly small mammals such as monkeys, squirrels, and rodents. Mpox also may be transmitted between humans through direct contact with bodily fluids, skin and mucosal lesions, respiratory droplets, or fomites. Mpox infection typically begins with a nonspecific flulike prodrome after a 5- to 21-day incubation period, followed by skin lesions of variable morphology affecting any region of the body. Clinically, mpox lesions have been reported to evolve through macular, papular, and vesiculopustular phases, followed by resolution with crusting. Lesions may occur anywhere on the body but frequently manifest on the face then spread centrifugally across the body, with various phases observed simultaneously.5 A worldwide outbreak in 2022 involved larger numbers of cases in nonendemic areas, primarily due to skin-to-skin contact, with predominant anal and genital localization of the lesions as well as fewer prodromal symptoms.6

The differential diagnosis of crusted and umbilicated papules includes disseminated herpesvirus infection, molluscum contagiosum, disseminated cryptococcosis, and histoplasmosis. Additional causative organisms to consider include Penicillium, Mycobacterium tuberculosis and nontuberculous mycobacteria, as well as Sporothrix schenckii.

Herpesvirus infections may have similar clinical and histopathologic findings to mpox. Histopathologically, herpes simplex virus (HSV) and varicella zoster virus (VZV) are essentially identical; both demonstrate ballooning and reticular epidermal degeneration, chromatin condensation, nuclear degeneration, multinucleated keratinocytes with steel-gray nuclei, and prominent epidermal acantholysis with an inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 1). However, involvement of folliculosebaceous units may favor a diagnosis of VZV. Immunohistochemical staining can further differentiate between HSV and VZV.7 While mpox may have features that overlap with both HSV and VZV, including ballooning degeneration and multinucleated keratinocytes with nuclear degeneration, acantholysis is a less commonly reported feature of mpox, and mpox virus infection is characterized by intracytoplasmic (Guarnieri) inclusion bodies rather than the intranuclear inclusion bodies of HSV and VZV.2,5 The presence of Guarnieri bodies in mpox may further help to distinguish mpox from HSV infection on routine histology.

Molluscum contagiosum infection typically manifests as multiple umbilicated papules at sites of inoculation. Large lesions may be seen in the setting of immunosuppression; however, they usually do not progress to vesicular, pustular, or crusted morphologies. Histopathology demonstrates a cup-shaped invagination of the epidermis into the dermis and proliferative rete ridges that descend downward and encircle the dermis with large eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion (Henderson-Patterson) bodies (Figure 2).8

Disseminated cryptococcus infection is caused by the invasive fungus Cryptococcus neoformans and is characterized by meningitis along with fever, malaise, headache, neck stiffness, photophobia, nausea, vomiting, pneumonia with cough and dyspnea, and skin rash, most commonly in immunocompromised individuals.9 Skin lesions are a sign of disseminated infection and can manifest as umbilicated or molluscumlike lesions. Histopathology of cryptococcosis demonstrates a granulomatous dermal infiltrate with neutrophils and pleomorphic yeasts measuring 4 µm to 6 µm with refringent capsules.10 Staining with Grocott methenamine silver and/or mucicarmine for yeast capsules can help to identify organisms (Figure 3).

Cutaneous histoplasmosis is caused by Histoplasma capsulatum, a dimorphic fungus that can lead to pulmonary, cutaneous, and disseminated disease, often in immunocompromised patients.11 Cutaneous disease may manifest with molluscumlike or verrucous papules and plaques. Histopathologic examination reveals diffuse suppurative and granulomatous infiltrates with foamy histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells, containing intracellular and extracellular yeasts measuring 1µm to 5µm, surrounded by a clear halo visible with Grocott methenamine silver stain (Figure 4).

×600). Grocott methenamine silver staining highlights numerous intracellular yeasts (inset, original magnification ×600).

Spreading cutaneous lesions in an immunocompromised individual may be the presentation of multiple infectious etiologies. With the recent rise in mpox cases occurring in nonendemic areas, clinicians should be aware of the spectrum of clinical findings that may occur. Notably, more than one infection may be present in severely immunocompromised individuals, as seen in our patient with chronic orolabial HSV-2 and acute mpox infection. Thorough clinical, histopathologic, and laboratory investigations are necessary for timely diagnosis, appropriate treatment, and exclusion of other life-threatening conditions.

- Moltrasio C, Boggio FL, Romagnuolo M, et al. Monkeypox: a histopathological and transmission electron microscopy study. Microorganisms. 2023;11:1781-1793. doi:10.3390/microorganisms11071781

- Ortins-Pina A, Hegemann B, Saggini A, et al. Histopathological features of human mpox: report of two cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2023;50:706-710. doi:10.1111/cup.14398

- Chalali F, Merlant M, Truong A, et al. Histological features associated with human mpox virus infection in 2022 outbreak in a nonendemic country. Clin Infect Dis. 21;76:1132-1135. doi:10.1093/cid/ciac856.

- Mpox (monkeypox). World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/health-topics/monkeypox/#tab=tab_1. Accessed August 6, 2025.

- Petersen E, Kantele A, Koopmans M, et al. Human monkeypox: epidemiologic and clinical characteristics, diagnosis, and prevention. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2019;33:1027-1043. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2019.03.001

- Philpott D, Hughes CM, Alroy KA, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of monkeypox cases — United States, May 17–July 22, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:1018-1022. doi:10.15585 /mmwr.mm7132e3

- Nikkels AF, Debrus S, Sadzot-Delvaux C, et al. Comparative immunohistochemical study of herpes simplex and varicella-zoster infections. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1993;422:121-126. doi:10.1007 /BF01607163

- Badri T, Gandhi GR. Molluscum Contagiosum. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Updated March 27, 2023. Accessed August 8, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441898/

- Mada PK, Jamil RT, Alam MU. Cryptococcus. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Updated August 7, 2023. Accessed August 8, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431060/

- Hayashida MZ, Seque CA, Pasin VP, et al. Disseminated cryptococcosis with skin lesions: report of a case series. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:69-72. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20176343

- Mustari AP, Rao S, Keshavamurthy V, et al. Dermoscopic evaluation of cutaneous histoplasmosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2023;19:1-4. doi:10.25259/IJDVL_889_2022

- Moltrasio C, Boggio FL, Romagnuolo M, et al. Monkeypox: a histopathological and transmission electron microscopy study. Microorganisms. 2023;11:1781-1793. doi:10.3390/microorganisms11071781

- Ortins-Pina A, Hegemann B, Saggini A, et al. Histopathological features of human mpox: report of two cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2023;50:706-710. doi:10.1111/cup.14398

- Chalali F, Merlant M, Truong A, et al. Histological features associated with human mpox virus infection in 2022 outbreak in a nonendemic country. Clin Infect Dis. 21;76:1132-1135. doi:10.1093/cid/ciac856.

- Mpox (monkeypox). World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/health-topics/monkeypox/#tab=tab_1. Accessed August 6, 2025.

- Petersen E, Kantele A, Koopmans M, et al. Human monkeypox: epidemiologic and clinical characteristics, diagnosis, and prevention. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2019;33:1027-1043. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2019.03.001

- Philpott D, Hughes CM, Alroy KA, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of monkeypox cases — United States, May 17–July 22, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:1018-1022. doi:10.15585 /mmwr.mm7132e3

- Nikkels AF, Debrus S, Sadzot-Delvaux C, et al. Comparative immunohistochemical study of herpes simplex and varicella-zoster infections. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1993;422:121-126. doi:10.1007 /BF01607163

- Badri T, Gandhi GR. Molluscum Contagiosum. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Updated March 27, 2023. Accessed August 8, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441898/

- Mada PK, Jamil RT, Alam MU. Cryptococcus. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Updated August 7, 2023. Accessed August 8, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431060/

- Hayashida MZ, Seque CA, Pasin VP, et al. Disseminated cryptococcosis with skin lesions: report of a case series. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:69-72. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20176343

- Mustari AP, Rao S, Keshavamurthy V, et al. Dermoscopic evaluation of cutaneous histoplasmosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2023;19:1-4. doi:10.25259/IJDVL_889_2022

Scattered Umbilicated Papules on the Cheek, Neck, and Arms

Scattered Umbilicated Papules on the Cheek, Neck, and Arms

A 42-year-old man with a history of multidrug-resistant HIV/AIDS presented to the emergency department for evaluation of pruritic, scattered, umbilicated papules on the left cheek, neck, and arms of 3 days’ duration. The patient’s most recent CD4+ T-cell count 6 weeks prior to the development of the rash was 1 cell/mm3. He was noncompliant with antiretroviral therapy. He reported that the lesions had progressed rapidly, starting on the face and extending down the neck and arms. Physical examination revealed scattered umbilicated and centrally crusted papules and plaques on the left cheek, neck, and arms. Erosions involving the oral mucosa also were noted, which the patient reported had been present for several weeks. An oral swab was positive for herpes simplex virus 2 on polymerase chain reaction. A shave biopsy of a lesion from the left cheek was performed.

Exophytic Papule on the Chin of a Child

Exophytic Papule on the Chin of a Child

THE DIAGNOSIS: Rhabdomyomatous Mesenchymal Hamartoma

Histopathologic examination of the excised tissue revealed haphazardly arranged bundles of mature striated muscle within the dermis and subcutaneous tissue admixed with adipose tissue, adnexal structures, blood vessels, and nerves. The presence of the lesion since birth, midline clinical presentation, and histologic findings were consistent with a diagnosis of rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma (RMH).

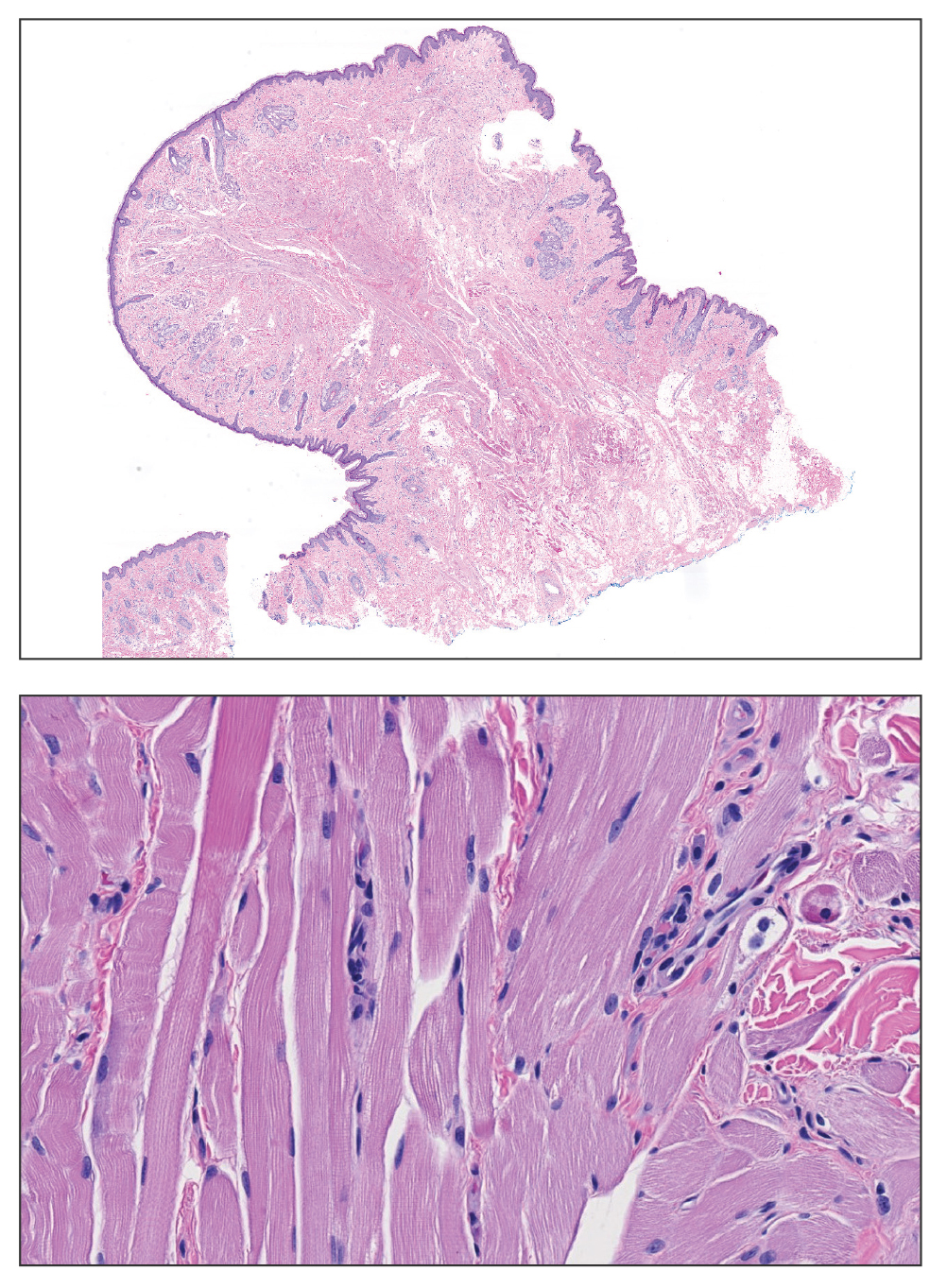

Also referred to as striated muscle hamartoma, RMH is a rare benign lesion thought to have embryonic origin due to its midline presentation.1 The etiology of RMH is unknown but is hypothesized to be due to abnormal migration or growth of embryonic mesenchymal tissue. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma typically manifests in infancy or early childhood as a solitary midline papule on the head or neck, although there have been rare reports of development in adulthood.2-4 Lesions often are polypoid or exophytic but may manifest as smooth papules or subcutaneous nodules.2 Although benign, RMH may be associated with other congenital abnormalities and conditions, such as Delleman syndrome, which is caused by a sporadic genetic abnormality and results in defects of the eye, central nervous system, and skin.5 Treatment for RMH is not needed, but surgical excision for cosmetic purposes can be performed with low risk for recurrence. Histologically, RMH demonstrates a normal epidermis overlying disorganized bundles of skeletal muscle accompanied by varying amounts of other mature dermal and subcutaneous tissues including nerves, blood vessels, adipose tissue, and other adnexal structures.2,6 Myoglobin and desmin are positive within the skeletal muscle bundles.7

Fibrous hamartoma of infancy (FHI) often manifests as a movable, ill-defined nodule within the subcutaneous tissue. While also occurring in young children—typically within the first 2 years of life—FHI primarily is found on the upper arms, back, and axillae, in contrast to FHI.8 The classic histopathologic presentation of FHI consists of a triphasic morphology consisting of undifferentiated mesenchymal cells and dense fibroblastic/myofibroblastic tissue with mature adipose tissue woven throughout in islands (Figure 1).9 Skeletal muscle is not a component of this tumor.

Neurofibromas also may manifest clinically as papules or nodules and arise from the peripheral nerve sheath. There are 3 major subtypes of neurofibromas—localized, diffuse, and plexiform—with the last being strongly associated with neurofibromatosis type 1.10 The plexiform type has a rare risk for malignant transformation. The typical histopathologic finding of a localized cutaneous neurofibroma is a dermal proliferation of spindle cells with wavy nuclei within a variably myxoid stroma (Figure 2).11 Interspersed mast cells also can be seen. A plexiform neurofibroma typically involves multiple nerve fascicles and comprises multinodular or tortuous bundles of cytologically bland spindle cells. Compared to RMH, skeletal muscle is not a component of this tumor.

Nevus lipomatosus superficialis is a benign hamartoma that can manifest as a pedunculated or exophytic papule. The lesions may be solitary or multiple and, unlike RMH, are most common on the buttocks, upper thighs, and trunk.12 The histopathologic features of nevus lipomatosus superficialis include clusters of mature adipose tissue in the superficial dermis admixed with collagen fibers and variably increased vasculature (Figure 3).13 Nevus lipomatosus superficialis does not contain skeletal muscle within the tumor in comparison to RMH.

It is important to distinguish rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) from RMH, as it is associated with increased mortality and morbidity. Rhabdomyosarcoma is the most common soft-tissue sarcoma in children and is derived from mesenchyme with variable degrees of skeletal muscle differentiation.14 Due to its mesenchymal origin, these tumors can manifest in a variety of places but most commonly on the head and neck and in the genital region.15 The most common subtype is embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma. Histologically, embryonal RMS shows a moderately cellular tumor composed of sheets of spindle-shaped or round cells with scant or eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 4). The absence of genetic translocation in the paired box-forkhead box protein 01 (PAX-FOXO1) gene helps distinguish it from solid alveolar RMS, the second most common and more aggressive subtype.12 Positive immunohistochemical staining for desmin, myoblast determination protein 1 (MyoD1), and myogenin supports myogenic differentiation.14

- Bernal-Mañas CM, Isaac-Montero MA, Vargas-Uribe MC, et al. Hamartoma mesenquimal rabdomiomatoso [rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma]. An Pediatr (Barc). 2013;78:260-262. doi:10.1016/j.anpedi.2012.08.005

- Al Amri R, De Stefano DV, Wang Q, et al. Morphologic spectrum of rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartomas (striated muscle hamartomas) in pediatric dermatopathology. Am J Dermatopathol. 2022;44:170-173. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000002062

- Carboni A, Fomin D. A rare adult presentation of a congenital tumor discovered incidentally after trauma. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;31:121-123. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.10.024

- Chang CP, Chen GS. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma: a plaque-type variant in an adult. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2005; 21(4):185-188. doi:10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70299-2

- Bahmani M, Naseri R, Iraniparast A, et al. Oculocerebrocutaneous syndrome (Delleman syndrome): a case with a novel presentation of orbital involvement. Case Rep Pediatr. 2021;2021:5524131. doi:10.1155/2021/5524131

- Kim H, Chung JH, Sung HM, et al. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma presenting as a midline mass on a chin. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2017;18:292-295. doi:10.7181/acfs.2017.18.4.292.

- Lin CP, Nguyen JM, Aboutalebi S, et al. Incidental rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2020;34:161-162. doi:10.1080/08998280.2020.1801087

- Ji Y, Hu P, Zhang C, et al. Fibrous hamartoma of infancy: radiologic features and literature review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20:356. doi:10.1186/s12891-019-2743-5

- Yu G, Wang Y, Wang G, et al. Fibrous hamartoma of infancy: a clinical pathological analysis of seventeen cases. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:3374-3377.

- Ferner RE, O’Doherty MJ. Neurofibroma and schwannoma. Curr Opin Neurol. 2002;15:679-684. doi:10.1097/01.wco.0000044763.39452.aa