User login

Dermatologists’ Perspectives Toward Disability Assessment: A Nationwide Survey Report

Dermatologists’ Perspectives Toward Disability Assessment: A Nationwide Survey Report

To the Editor:

Cutaneous medical conditions can have a substantial impact on patients’ functioning and quality of life. Many patients with severe skin disease are eligible to receive disability assistance that can provide them with essential income and health care. Previous research has highlighted disability assessment as one of the most important ways physicians can help mitigate the health consequences of poverty.1 Dermatologists can play an important role in the disability assessment process by documenting the facts associated with patients’ skin conditions.

Although skin conditions have a relatively high prevalence, they remain underrepresented in disability claims. Between 1997 and 2004, occupational skin diseases accounted for 12% to 17% of nonfatal work-related illnesses; however, during that same period, skin conditions comprised only 0.21% of disability claims in the United States.2,3 Historically, there has been hesitancy among dermatologists to complete disability paperwork; a 1976 survey of dermatologists cited extensive paperwork, “troublesome patients,” and fee schedule issues as reasons.4 The lack of training regarding disability assessment in medical school and residency also has been noted.5

To characterize modern attitudes toward disability assessments, we conducted a survey of dermatologists across the United States. Our study was reviewed and declared exempt by the institutional review board of the Lundquist Institute for Biomedical Innovation at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center (Torrance, California)(approval #18CR-32242-01). Using convenience sampling, we emailed dermatologists from the Association of Professors of Dermatology and dermatology state societies in all 50 states inviting them to participate in our voluntary and anonymous survey, which was administered using SurveyMonkey. The use of all society mailing lists was approved by the respective owners. The 15-question survey included multiple choice, Likert scale, and free response sections. Summary and descriptive statistics were used to describe respondent demographics and identify any patterns in responses.

For each Likert-based question, participants ranked their degree of agreement with a statement as: 1=strongly disagree, 2=somewhat disagree, 3=neither agree nor disagree/neutral, 4=somewhat agree, and 5=strongly agree. The mean response and standard deviation were reported for each Likert scale prompt. Preplanned 1-sample t testing was used to analyze Likert scale data, in which the mean response for each prompt was compared to a baseline response of 3 (neutral). A P value <.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics for MacOS, version 27 (IBM).

Seventy-eight dermatologists agreed to participate, and 70 completed the survey, for a response rate of 89.7% (Table 1). The dermatologists we surveyed practiced in a variety of clinical settings, including academic public hospitals (46.2% [36/78]), academic private hospitals (33.3% [26/78]), and private practices (32.1% [25/78]), and 60.3% (47/78) reported providing disability documentation at some point. Most of the respondents (64.3% [45/70]) did not perform assessments in an average month (Table 2). Medical assessment documentation was provided most frequently for workers’ compensation (50.0% [35/70]), private insurance (27.1% [19/70]), and Social Security Disability Insurance (25.7% [18/70]). Dermatologists overwhelmingly reported no formal training for disability assessment in medical school (94.3% [66/70]), residency (97.1% [68/70]), or clinical practice (81.4% [57/70]).

In the Likert scale prompts, respondents agreed that they were uncertain of their role in disability assessment (mean response, 3.6; P<.001). Moreover, they were uncomfortable providing assessments (mean response, 3.5; P<.001) and felt that they did not have sufficient time to perform them (mean response, 3.6; P<.001). Dermatologists disagreed that they received adequate compensation for performing assessments (mean response, 2.2; P<.001) and felt that they did not have enough time to participate in assessments (mean response, 3.6; P<.001). Respondents generally did not feel distrustful of patients seeking disability assessment (mean response, 2.8; P=.043). Dermatologists neither agreed nor disagreed when asked if they thought that physicians can determine disability status (mean response, 3.2; P=.118). The details of the Likert scale responses are described in Table 3. Respondents also were uncertain as to which dermatologic conditions were eligible for disability. When asked to select which conditions from a list of 10 were eligible per the Social Security Administration listing of disability impairments, only 15.4% (12/70) of respondents correctly identified that all the conditions qualified; these included ichthyosis, pemphigus vulgaris, allergic contact dermatitis, hidradenitis suppurativa, systemic lupus erythematosus, chromoblastomycosis, xeroderma pigmentosum, burns, malignant melanoma, and scleroderma.6

In the free-response prompts, respondents frequently described extensive paperwork, inadequate time, and lack of reimbursement as barriers to providing documentation. Often, dermatologists found that the forms were not well matched to the skin conditions they were evaluating and rather had a musculoskeletal focus. Multiple individuals commented on the challenge in assessing the percentage of disability and functional/psychosocial impairment in skin conditions. One respondent noted that workers’ compensation forms ask if the patient is “…permanent and stationary…for most conditions this has no meaning in dermatology.” Some felt hesitant to provide documentation because they had insufficient patient history, especially regarding employment, and opted to defer to primary care providers who might be more familiar with the full patient history.

A dermatologist described their perspective as follows:

“…As a specialist I feel that I don’t have a complete look into all the factors that could contribute to a patient[’]s need to go on disability, and I don’t have experience with filling out disability requests. That being said, if a patient[’]s request for disability was due to a skin disease that I know way more about than [a] primary care [physician] would, I would do the disability assessment.”

Another respondent noted the complexity in “establishing causality” for workers’ compensation. Another dermatologist reported,

“The most frequent challenging situation I encounter is being asked to evaluate for maximum medical improvement after patch testing. If the patient is not fully avoiding contact allergens either at home or at work, then I typically document that they are not at [maximum medical improvement]. The reality is that most frequently it is due to exposure to allergens at home so the line between what is a legitimate worker’s comp[ensation] issue and what is a home life choice is blurry.”

Nevertheless, respondents expressed interest in learning more about disability assessment procedures. Summary guides, lectures, and prefilled paperwork were the most popular initiatives that respondents agreed would be beneficial toward becoming educated regarding disability assessment (78.6%, 58.6%, and 58.6%, respectively)(Table 2). One respondent noted that “previous [internal medicine] history help[ed]” them in performing cutaneous disability assessments.

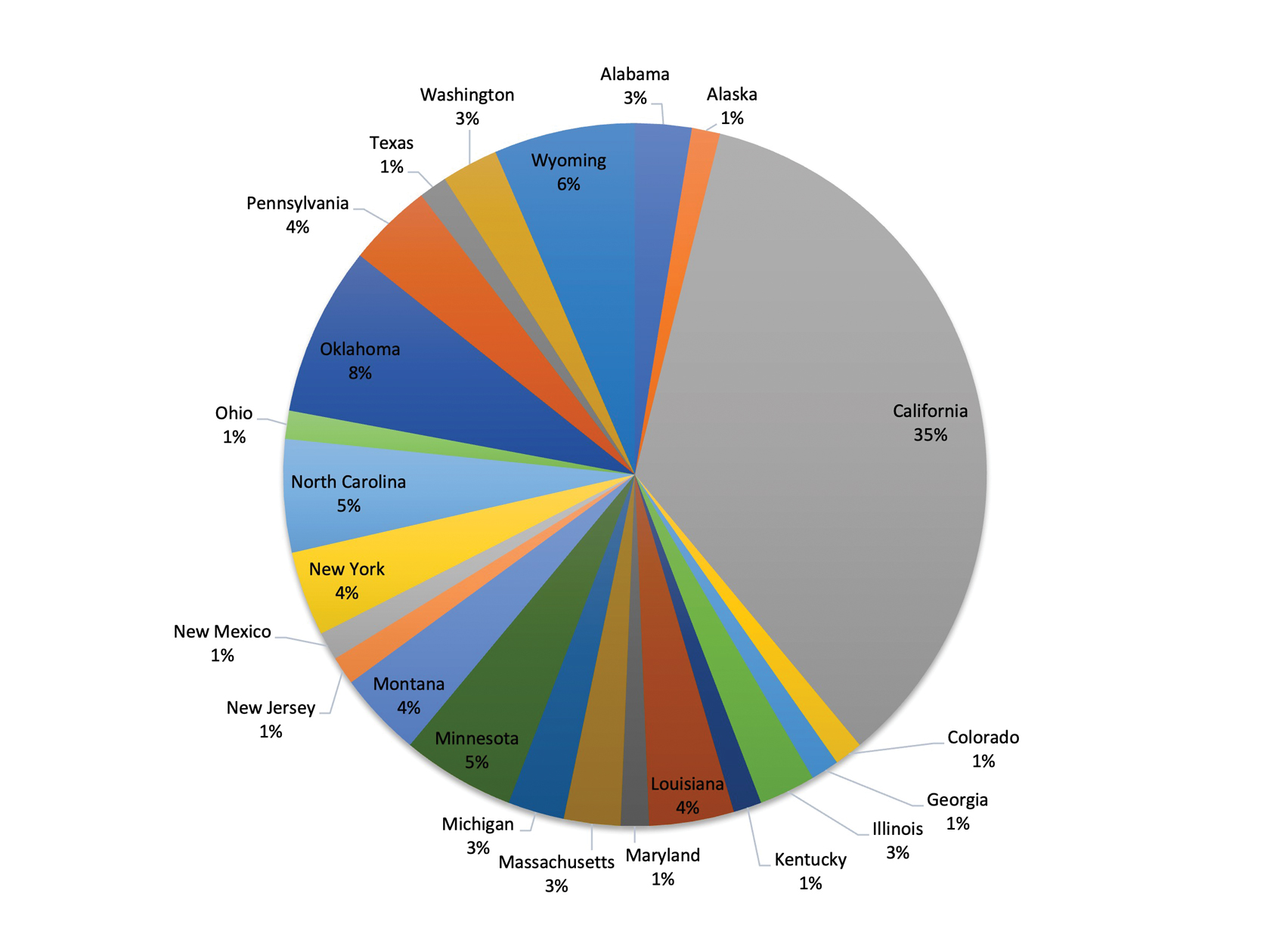

As with any survey, our study did have some inherent limitations. Only a relatively small sample size was willing to complete the survey. There was a predominance of respondents from California (34.6% [27/78]), as well as those practicing for less than 15 years (58.9% [46/78])(Figure). This could limit generalizability to the national population of dermatologists. In addition, there was potential for recall bias and errors in responding given the self-reported nature of the study. Different individuals may interpret the Likert scale options in various ways, which could skew results unintentionally. However, the survey was largely qualitative in nature, making it a legitimate tool for answering our research questions. Moreover, we were able to hear the perspectives of dermatologists across diverse practice settings, with free response prompts to increase the depth of the survey.

Almost 50 years later, our survey echoes common themes from Adams’ 1976 survey.4 Inadequate compensation, limited time, and burdensome paperwork all continue to hinder dermatologists’ ability to perform disability assessments. Our participants frequently commented that the current disability forms are not congruent with the nature of skin conditions, making it challenging to accurately document the facts.

Moreover, respondents felt uncertain in their role in disability assessment and occasionally noted distrust of patients or insufficient patient history as barriers to completing assessments. They also were unsure if physicians can grant disability status. This is a common misconception among physicians that leads to discomfort in helping with disability assessment.7 The role of physicians in disability assessment is to document the facts of a patient’s illness, not to determine whether they are eligible for benefits. We discovered uncertainty in our respondents’ ability to identify conditions eligible for disability, highlighting an area in need of greater education for physicians.

Despite these obstacles, respondents were interested in learning more about disability assessment and highlighted several practical approaches that could help them better perform this task. As skin specialists, dermatologists are the best-equipped physicians to assess cutaneous conditions and should play a greater role in performing disability assessments, which could be achieved through increased educational initiatives and individual physician motivation.7 We call for greater collaboration and reflection on the importance of disability assistance among dermatologists to increase participation in the disability-assessment process.

- O’Connell JJ, Zevin BD, Quick PD, et al. Documenting disability: simple strategies for medical providers. Health Care for the Homeless Clinicians’ Network. September 2007. Accessed March 31, 2025. https://nhchc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/DocumentingDisability2007.pdf

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Injuries, illnesses, and fatalities. Accessed March 31, 2025. https://www.bls.gov/iif/

- Meseguer J. Outcome variation in the Social Security Disability Insurance Program: the role of primary diagnoses. Soc Secur Bull. 2013;73:39-75.

- Adams RM. Attitudes of California dermatologists toward Worker’s Compensation: results of a survey. West J Med. 1976;125:169-175.

- Talmage J, Melhorn J, Hyman M. AMA Guides to the Evaluation of Work Ability and Return to Work. 2nd ed. American Medical Association; 2011.

- Social Security Administration. Disability evaluation under Social Security. 8.00 skin disorders - adult. March 31, 2025. https://www.ssa.gov/disability/professionals/bluebook/8.00-Skin-Adult.htm

- Dawson J, Smogorzewski J. Demystifying disability assessments for dermatologists—a call to action. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:903-904. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.1767

To the Editor:

Cutaneous medical conditions can have a substantial impact on patients’ functioning and quality of life. Many patients with severe skin disease are eligible to receive disability assistance that can provide them with essential income and health care. Previous research has highlighted disability assessment as one of the most important ways physicians can help mitigate the health consequences of poverty.1 Dermatologists can play an important role in the disability assessment process by documenting the facts associated with patients’ skin conditions.

Although skin conditions have a relatively high prevalence, they remain underrepresented in disability claims. Between 1997 and 2004, occupational skin diseases accounted for 12% to 17% of nonfatal work-related illnesses; however, during that same period, skin conditions comprised only 0.21% of disability claims in the United States.2,3 Historically, there has been hesitancy among dermatologists to complete disability paperwork; a 1976 survey of dermatologists cited extensive paperwork, “troublesome patients,” and fee schedule issues as reasons.4 The lack of training regarding disability assessment in medical school and residency also has been noted.5

To characterize modern attitudes toward disability assessments, we conducted a survey of dermatologists across the United States. Our study was reviewed and declared exempt by the institutional review board of the Lundquist Institute for Biomedical Innovation at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center (Torrance, California)(approval #18CR-32242-01). Using convenience sampling, we emailed dermatologists from the Association of Professors of Dermatology and dermatology state societies in all 50 states inviting them to participate in our voluntary and anonymous survey, which was administered using SurveyMonkey. The use of all society mailing lists was approved by the respective owners. The 15-question survey included multiple choice, Likert scale, and free response sections. Summary and descriptive statistics were used to describe respondent demographics and identify any patterns in responses.

For each Likert-based question, participants ranked their degree of agreement with a statement as: 1=strongly disagree, 2=somewhat disagree, 3=neither agree nor disagree/neutral, 4=somewhat agree, and 5=strongly agree. The mean response and standard deviation were reported for each Likert scale prompt. Preplanned 1-sample t testing was used to analyze Likert scale data, in which the mean response for each prompt was compared to a baseline response of 3 (neutral). A P value <.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics for MacOS, version 27 (IBM).

Seventy-eight dermatologists agreed to participate, and 70 completed the survey, for a response rate of 89.7% (Table 1). The dermatologists we surveyed practiced in a variety of clinical settings, including academic public hospitals (46.2% [36/78]), academic private hospitals (33.3% [26/78]), and private practices (32.1% [25/78]), and 60.3% (47/78) reported providing disability documentation at some point. Most of the respondents (64.3% [45/70]) did not perform assessments in an average month (Table 2). Medical assessment documentation was provided most frequently for workers’ compensation (50.0% [35/70]), private insurance (27.1% [19/70]), and Social Security Disability Insurance (25.7% [18/70]). Dermatologists overwhelmingly reported no formal training for disability assessment in medical school (94.3% [66/70]), residency (97.1% [68/70]), or clinical practice (81.4% [57/70]).

In the Likert scale prompts, respondents agreed that they were uncertain of their role in disability assessment (mean response, 3.6; P<.001). Moreover, they were uncomfortable providing assessments (mean response, 3.5; P<.001) and felt that they did not have sufficient time to perform them (mean response, 3.6; P<.001). Dermatologists disagreed that they received adequate compensation for performing assessments (mean response, 2.2; P<.001) and felt that they did not have enough time to participate in assessments (mean response, 3.6; P<.001). Respondents generally did not feel distrustful of patients seeking disability assessment (mean response, 2.8; P=.043). Dermatologists neither agreed nor disagreed when asked if they thought that physicians can determine disability status (mean response, 3.2; P=.118). The details of the Likert scale responses are described in Table 3. Respondents also were uncertain as to which dermatologic conditions were eligible for disability. When asked to select which conditions from a list of 10 were eligible per the Social Security Administration listing of disability impairments, only 15.4% (12/70) of respondents correctly identified that all the conditions qualified; these included ichthyosis, pemphigus vulgaris, allergic contact dermatitis, hidradenitis suppurativa, systemic lupus erythematosus, chromoblastomycosis, xeroderma pigmentosum, burns, malignant melanoma, and scleroderma.6

In the free-response prompts, respondents frequently described extensive paperwork, inadequate time, and lack of reimbursement as barriers to providing documentation. Often, dermatologists found that the forms were not well matched to the skin conditions they were evaluating and rather had a musculoskeletal focus. Multiple individuals commented on the challenge in assessing the percentage of disability and functional/psychosocial impairment in skin conditions. One respondent noted that workers’ compensation forms ask if the patient is “…permanent and stationary…for most conditions this has no meaning in dermatology.” Some felt hesitant to provide documentation because they had insufficient patient history, especially regarding employment, and opted to defer to primary care providers who might be more familiar with the full patient history.

A dermatologist described their perspective as follows:

“…As a specialist I feel that I don’t have a complete look into all the factors that could contribute to a patient[’]s need to go on disability, and I don’t have experience with filling out disability requests. That being said, if a patient[’]s request for disability was due to a skin disease that I know way more about than [a] primary care [physician] would, I would do the disability assessment.”

Another respondent noted the complexity in “establishing causality” for workers’ compensation. Another dermatologist reported,

“The most frequent challenging situation I encounter is being asked to evaluate for maximum medical improvement after patch testing. If the patient is not fully avoiding contact allergens either at home or at work, then I typically document that they are not at [maximum medical improvement]. The reality is that most frequently it is due to exposure to allergens at home so the line between what is a legitimate worker’s comp[ensation] issue and what is a home life choice is blurry.”

Nevertheless, respondents expressed interest in learning more about disability assessment procedures. Summary guides, lectures, and prefilled paperwork were the most popular initiatives that respondents agreed would be beneficial toward becoming educated regarding disability assessment (78.6%, 58.6%, and 58.6%, respectively)(Table 2). One respondent noted that “previous [internal medicine] history help[ed]” them in performing cutaneous disability assessments.

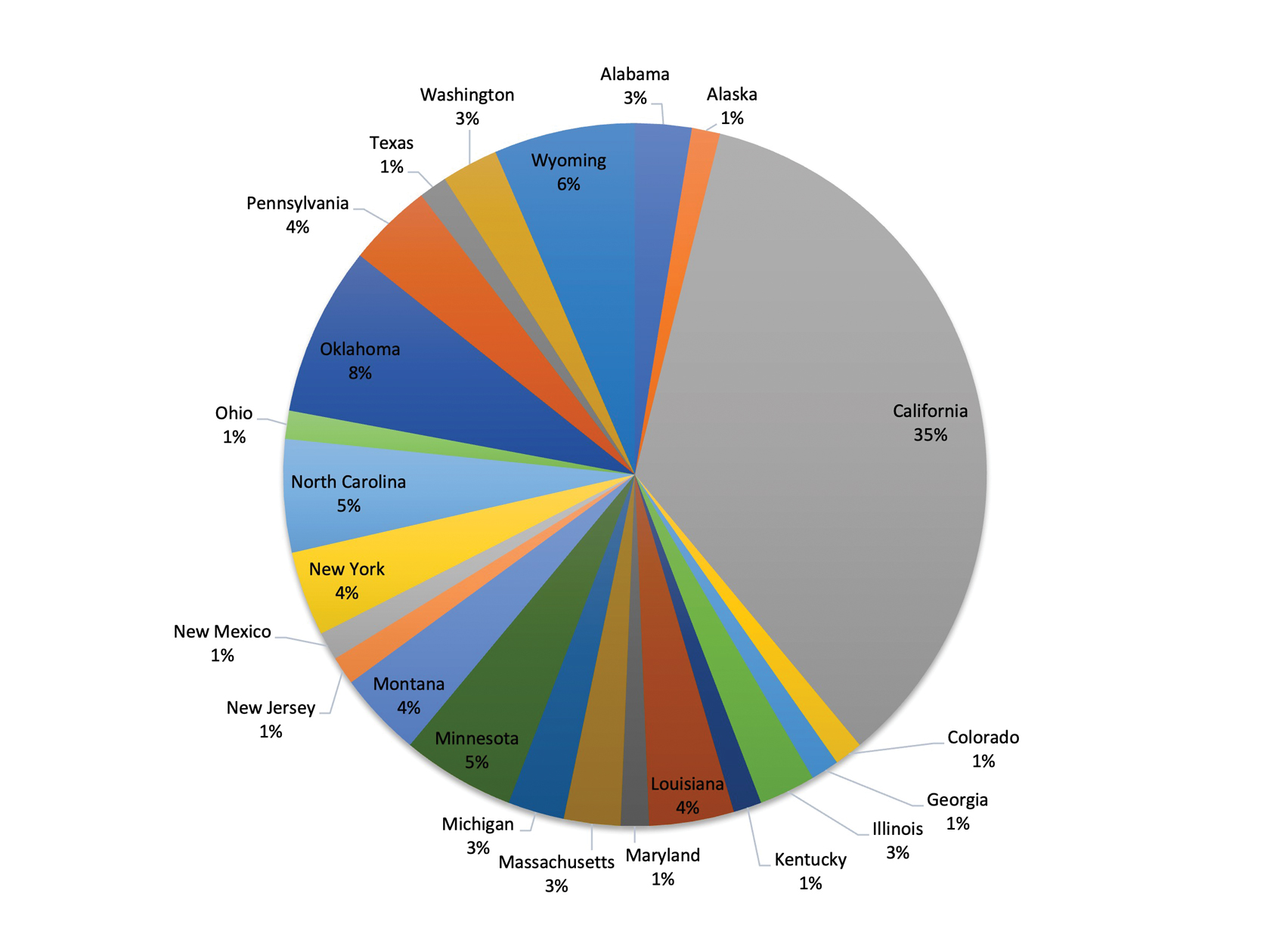

As with any survey, our study did have some inherent limitations. Only a relatively small sample size was willing to complete the survey. There was a predominance of respondents from California (34.6% [27/78]), as well as those practicing for less than 15 years (58.9% [46/78])(Figure). This could limit generalizability to the national population of dermatologists. In addition, there was potential for recall bias and errors in responding given the self-reported nature of the study. Different individuals may interpret the Likert scale options in various ways, which could skew results unintentionally. However, the survey was largely qualitative in nature, making it a legitimate tool for answering our research questions. Moreover, we were able to hear the perspectives of dermatologists across diverse practice settings, with free response prompts to increase the depth of the survey.

Almost 50 years later, our survey echoes common themes from Adams’ 1976 survey.4 Inadequate compensation, limited time, and burdensome paperwork all continue to hinder dermatologists’ ability to perform disability assessments. Our participants frequently commented that the current disability forms are not congruent with the nature of skin conditions, making it challenging to accurately document the facts.

Moreover, respondents felt uncertain in their role in disability assessment and occasionally noted distrust of patients or insufficient patient history as barriers to completing assessments. They also were unsure if physicians can grant disability status. This is a common misconception among physicians that leads to discomfort in helping with disability assessment.7 The role of physicians in disability assessment is to document the facts of a patient’s illness, not to determine whether they are eligible for benefits. We discovered uncertainty in our respondents’ ability to identify conditions eligible for disability, highlighting an area in need of greater education for physicians.

Despite these obstacles, respondents were interested in learning more about disability assessment and highlighted several practical approaches that could help them better perform this task. As skin specialists, dermatologists are the best-equipped physicians to assess cutaneous conditions and should play a greater role in performing disability assessments, which could be achieved through increased educational initiatives and individual physician motivation.7 We call for greater collaboration and reflection on the importance of disability assistance among dermatologists to increase participation in the disability-assessment process.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous medical conditions can have a substantial impact on patients’ functioning and quality of life. Many patients with severe skin disease are eligible to receive disability assistance that can provide them with essential income and health care. Previous research has highlighted disability assessment as one of the most important ways physicians can help mitigate the health consequences of poverty.1 Dermatologists can play an important role in the disability assessment process by documenting the facts associated with patients’ skin conditions.

Although skin conditions have a relatively high prevalence, they remain underrepresented in disability claims. Between 1997 and 2004, occupational skin diseases accounted for 12% to 17% of nonfatal work-related illnesses; however, during that same period, skin conditions comprised only 0.21% of disability claims in the United States.2,3 Historically, there has been hesitancy among dermatologists to complete disability paperwork; a 1976 survey of dermatologists cited extensive paperwork, “troublesome patients,” and fee schedule issues as reasons.4 The lack of training regarding disability assessment in medical school and residency also has been noted.5

To characterize modern attitudes toward disability assessments, we conducted a survey of dermatologists across the United States. Our study was reviewed and declared exempt by the institutional review board of the Lundquist Institute for Biomedical Innovation at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center (Torrance, California)(approval #18CR-32242-01). Using convenience sampling, we emailed dermatologists from the Association of Professors of Dermatology and dermatology state societies in all 50 states inviting them to participate in our voluntary and anonymous survey, which was administered using SurveyMonkey. The use of all society mailing lists was approved by the respective owners. The 15-question survey included multiple choice, Likert scale, and free response sections. Summary and descriptive statistics were used to describe respondent demographics and identify any patterns in responses.

For each Likert-based question, participants ranked their degree of agreement with a statement as: 1=strongly disagree, 2=somewhat disagree, 3=neither agree nor disagree/neutral, 4=somewhat agree, and 5=strongly agree. The mean response and standard deviation were reported for each Likert scale prompt. Preplanned 1-sample t testing was used to analyze Likert scale data, in which the mean response for each prompt was compared to a baseline response of 3 (neutral). A P value <.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics for MacOS, version 27 (IBM).

Seventy-eight dermatologists agreed to participate, and 70 completed the survey, for a response rate of 89.7% (Table 1). The dermatologists we surveyed practiced in a variety of clinical settings, including academic public hospitals (46.2% [36/78]), academic private hospitals (33.3% [26/78]), and private practices (32.1% [25/78]), and 60.3% (47/78) reported providing disability documentation at some point. Most of the respondents (64.3% [45/70]) did not perform assessments in an average month (Table 2). Medical assessment documentation was provided most frequently for workers’ compensation (50.0% [35/70]), private insurance (27.1% [19/70]), and Social Security Disability Insurance (25.7% [18/70]). Dermatologists overwhelmingly reported no formal training for disability assessment in medical school (94.3% [66/70]), residency (97.1% [68/70]), or clinical practice (81.4% [57/70]).

In the Likert scale prompts, respondents agreed that they were uncertain of their role in disability assessment (mean response, 3.6; P<.001). Moreover, they were uncomfortable providing assessments (mean response, 3.5; P<.001) and felt that they did not have sufficient time to perform them (mean response, 3.6; P<.001). Dermatologists disagreed that they received adequate compensation for performing assessments (mean response, 2.2; P<.001) and felt that they did not have enough time to participate in assessments (mean response, 3.6; P<.001). Respondents generally did not feel distrustful of patients seeking disability assessment (mean response, 2.8; P=.043). Dermatologists neither agreed nor disagreed when asked if they thought that physicians can determine disability status (mean response, 3.2; P=.118). The details of the Likert scale responses are described in Table 3. Respondents also were uncertain as to which dermatologic conditions were eligible for disability. When asked to select which conditions from a list of 10 were eligible per the Social Security Administration listing of disability impairments, only 15.4% (12/70) of respondents correctly identified that all the conditions qualified; these included ichthyosis, pemphigus vulgaris, allergic contact dermatitis, hidradenitis suppurativa, systemic lupus erythematosus, chromoblastomycosis, xeroderma pigmentosum, burns, malignant melanoma, and scleroderma.6

In the free-response prompts, respondents frequently described extensive paperwork, inadequate time, and lack of reimbursement as barriers to providing documentation. Often, dermatologists found that the forms were not well matched to the skin conditions they were evaluating and rather had a musculoskeletal focus. Multiple individuals commented on the challenge in assessing the percentage of disability and functional/psychosocial impairment in skin conditions. One respondent noted that workers’ compensation forms ask if the patient is “…permanent and stationary…for most conditions this has no meaning in dermatology.” Some felt hesitant to provide documentation because they had insufficient patient history, especially regarding employment, and opted to defer to primary care providers who might be more familiar with the full patient history.

A dermatologist described their perspective as follows:

“…As a specialist I feel that I don’t have a complete look into all the factors that could contribute to a patient[’]s need to go on disability, and I don’t have experience with filling out disability requests. That being said, if a patient[’]s request for disability was due to a skin disease that I know way more about than [a] primary care [physician] would, I would do the disability assessment.”

Another respondent noted the complexity in “establishing causality” for workers’ compensation. Another dermatologist reported,

“The most frequent challenging situation I encounter is being asked to evaluate for maximum medical improvement after patch testing. If the patient is not fully avoiding contact allergens either at home or at work, then I typically document that they are not at [maximum medical improvement]. The reality is that most frequently it is due to exposure to allergens at home so the line between what is a legitimate worker’s comp[ensation] issue and what is a home life choice is blurry.”

Nevertheless, respondents expressed interest in learning more about disability assessment procedures. Summary guides, lectures, and prefilled paperwork were the most popular initiatives that respondents agreed would be beneficial toward becoming educated regarding disability assessment (78.6%, 58.6%, and 58.6%, respectively)(Table 2). One respondent noted that “previous [internal medicine] history help[ed]” them in performing cutaneous disability assessments.

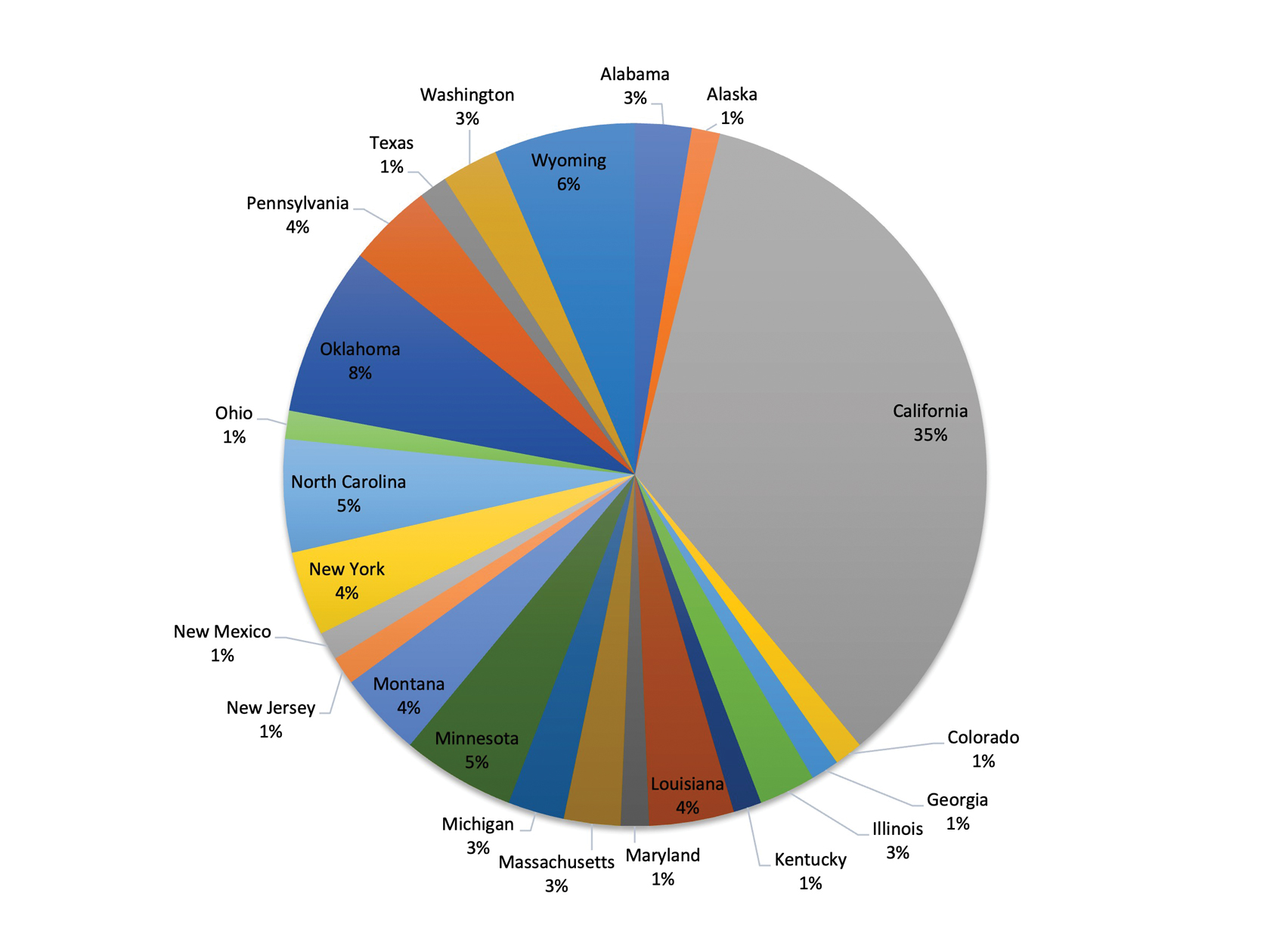

As with any survey, our study did have some inherent limitations. Only a relatively small sample size was willing to complete the survey. There was a predominance of respondents from California (34.6% [27/78]), as well as those practicing for less than 15 years (58.9% [46/78])(Figure). This could limit generalizability to the national population of dermatologists. In addition, there was potential for recall bias and errors in responding given the self-reported nature of the study. Different individuals may interpret the Likert scale options in various ways, which could skew results unintentionally. However, the survey was largely qualitative in nature, making it a legitimate tool for answering our research questions. Moreover, we were able to hear the perspectives of dermatologists across diverse practice settings, with free response prompts to increase the depth of the survey.

Almost 50 years later, our survey echoes common themes from Adams’ 1976 survey.4 Inadequate compensation, limited time, and burdensome paperwork all continue to hinder dermatologists’ ability to perform disability assessments. Our participants frequently commented that the current disability forms are not congruent with the nature of skin conditions, making it challenging to accurately document the facts.

Moreover, respondents felt uncertain in their role in disability assessment and occasionally noted distrust of patients or insufficient patient history as barriers to completing assessments. They also were unsure if physicians can grant disability status. This is a common misconception among physicians that leads to discomfort in helping with disability assessment.7 The role of physicians in disability assessment is to document the facts of a patient’s illness, not to determine whether they are eligible for benefits. We discovered uncertainty in our respondents’ ability to identify conditions eligible for disability, highlighting an area in need of greater education for physicians.

Despite these obstacles, respondents were interested in learning more about disability assessment and highlighted several practical approaches that could help them better perform this task. As skin specialists, dermatologists are the best-equipped physicians to assess cutaneous conditions and should play a greater role in performing disability assessments, which could be achieved through increased educational initiatives and individual physician motivation.7 We call for greater collaboration and reflection on the importance of disability assistance among dermatologists to increase participation in the disability-assessment process.

- O’Connell JJ, Zevin BD, Quick PD, et al. Documenting disability: simple strategies for medical providers. Health Care for the Homeless Clinicians’ Network. September 2007. Accessed March 31, 2025. https://nhchc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/DocumentingDisability2007.pdf

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Injuries, illnesses, and fatalities. Accessed March 31, 2025. https://www.bls.gov/iif/

- Meseguer J. Outcome variation in the Social Security Disability Insurance Program: the role of primary diagnoses. Soc Secur Bull. 2013;73:39-75.

- Adams RM. Attitudes of California dermatologists toward Worker’s Compensation: results of a survey. West J Med. 1976;125:169-175.

- Talmage J, Melhorn J, Hyman M. AMA Guides to the Evaluation of Work Ability and Return to Work. 2nd ed. American Medical Association; 2011.

- Social Security Administration. Disability evaluation under Social Security. 8.00 skin disorders - adult. March 31, 2025. https://www.ssa.gov/disability/professionals/bluebook/8.00-Skin-Adult.htm

- Dawson J, Smogorzewski J. Demystifying disability assessments for dermatologists—a call to action. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:903-904. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.1767

- O’Connell JJ, Zevin BD, Quick PD, et al. Documenting disability: simple strategies for medical providers. Health Care for the Homeless Clinicians’ Network. September 2007. Accessed March 31, 2025. https://nhchc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/DocumentingDisability2007.pdf

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Injuries, illnesses, and fatalities. Accessed March 31, 2025. https://www.bls.gov/iif/

- Meseguer J. Outcome variation in the Social Security Disability Insurance Program: the role of primary diagnoses. Soc Secur Bull. 2013;73:39-75.

- Adams RM. Attitudes of California dermatologists toward Worker’s Compensation: results of a survey. West J Med. 1976;125:169-175.

- Talmage J, Melhorn J, Hyman M. AMA Guides to the Evaluation of Work Ability and Return to Work. 2nd ed. American Medical Association; 2011.

- Social Security Administration. Disability evaluation under Social Security. 8.00 skin disorders - adult. March 31, 2025. https://www.ssa.gov/disability/professionals/bluebook/8.00-Skin-Adult.htm

- Dawson J, Smogorzewski J. Demystifying disability assessments for dermatologists—a call to action. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:903-904. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.1767

Dermatologists’ Perspectives Toward Disability Assessment: A Nationwide Survey Report

Dermatologists’ Perspectives Toward Disability Assessment: A Nationwide Survey Report

PRACTICE POINTS

- As experts in skin conditions, dermatologists are most qualified to assist with disability assessment for dermatologic concerns.

- There are several barriers to dermatologists participating in the disability assessment process, including lack of time, compensation, and education on the subject.

- Many dermatologists may be interested in learning more about disability assessment, and education could be provided in the form of summary guides, lectures, and prefilled paperwork.