User login

Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis Secondary to Application of Tapinarof Cream 1%

Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis Secondary to Application of Tapinarof Cream 1%

To the Editor:

For many years, topical treatment of plaque psoriasis was limited to steroids, calcineurin inhibitors, vitamin D analogs, retinoids, coal tar products, and anthralin. In recent years, 2 new nonsteroidal treatment options with alternative mechanisms of action, roflumilast 0.3% and tapinarof 1%, have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.1 Roflumilast 0.3%, a topical phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, was shown in phase 3 clinical trials to reach an Investigator Global Assessment response of 37.5% to 42.2% in 8 weeks using once-daily application with minimal cutaneous adverse effects.1 Furthermore, it has demonstrated efficacy in treating psoriasis in intertriginous areas in subset analyses.1 Tapinarof is an aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist that suppresses Th17 cell differentiation by downregulating IL-17, IL-22, and IL-23.1 In phase 3 clinical trials, 35% to 40% of patients who used tapinarof cream 1% once daily demonstrated improvement in psoriasis compared with 6% who used the vehicle alone.2 In these studies, 18% to 24% of patients who used tapinarof cream 1% experienced folliculitis.2

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is a nonfollicular pustular drug reaction with systemic symptoms that typically occurs within 2 weeks of exposure to an inciting medication. Systemic antibiotics are the most commonly reported cause of AGEP.3 There are few reports in the literature of AGEP induced by topical agents.4,5 We report a case of AGEP in a young man following the use of tapinarof cream 1%.

A 23-year-old man with a history of psoriasis presented to the emergency department with fever and a pustular rash. One week prior to presentation, he developed a pustular eruption around plaques of psoriasis on the arms and legs. The patient had been prescribed tapinarof cream 1% by an outside dermatologist and was applying the medication to the affected areas once daily for 1 month prior to onset of symptoms. He discontinued tapinarof a few days prior to the eruption starting, but the rash progressed centrifugally and was associated with fevers and fatigue despite treatment with a brief course of empiric cephalexin prescribed by his primary care provider.

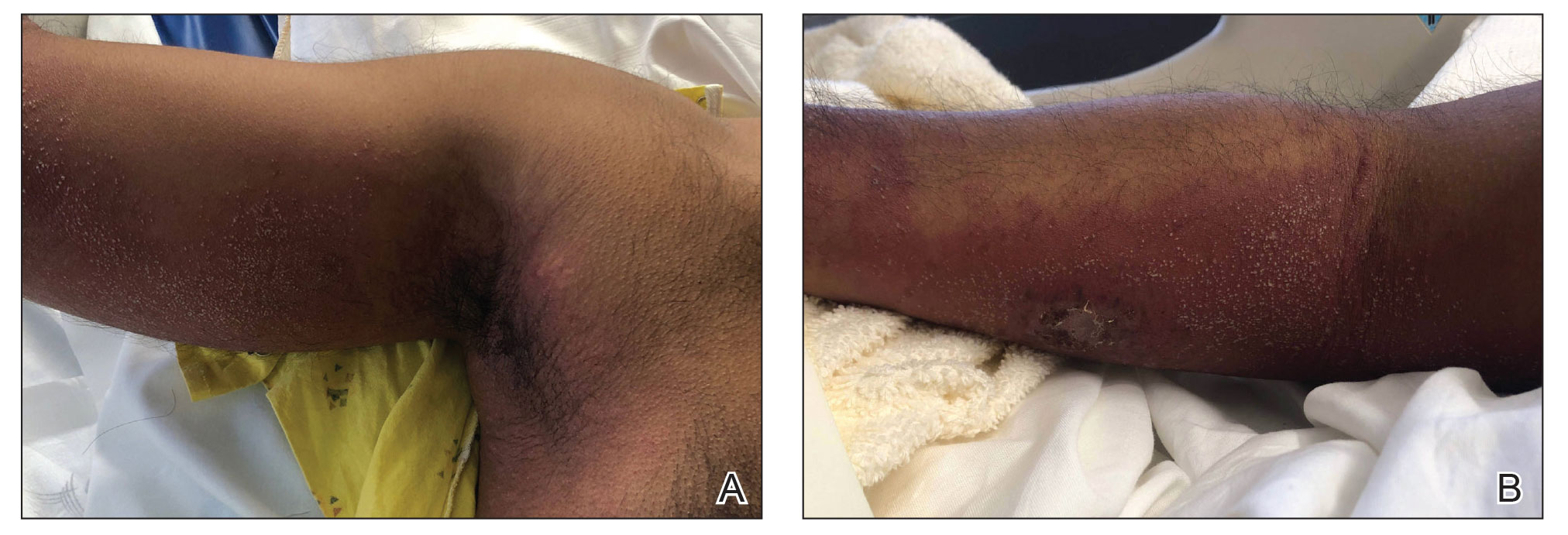

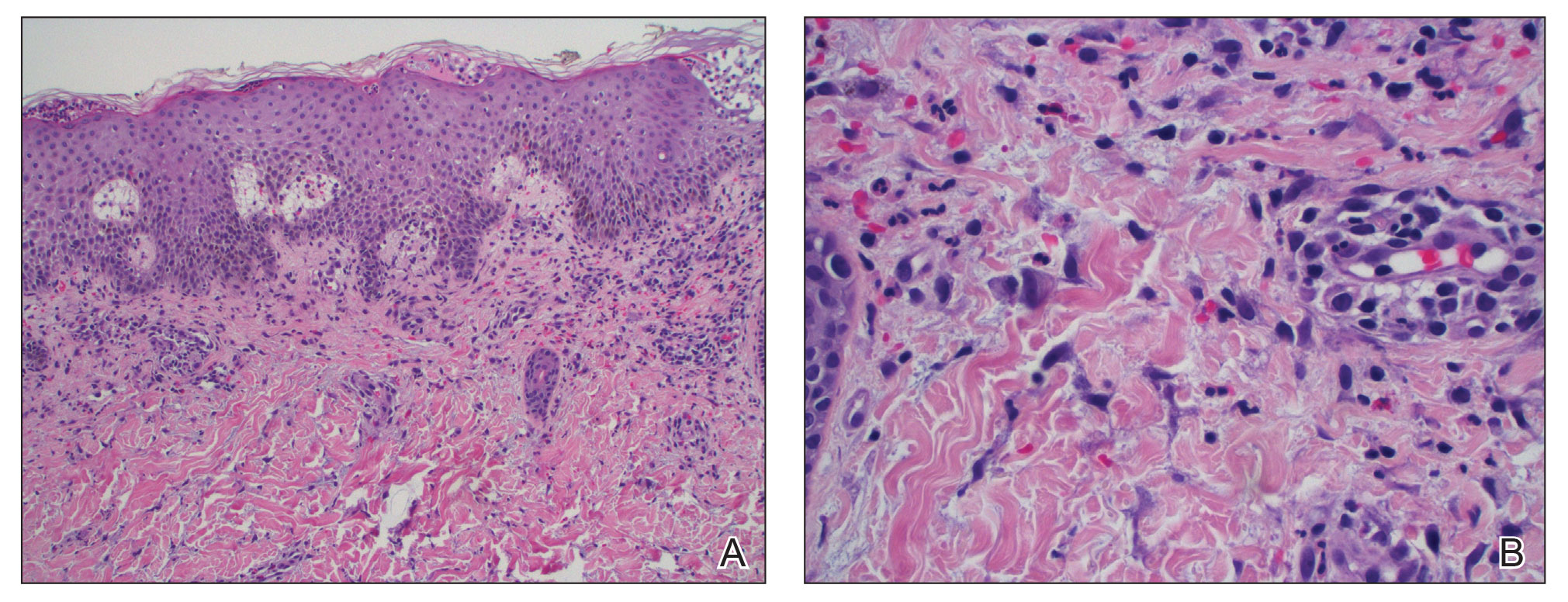

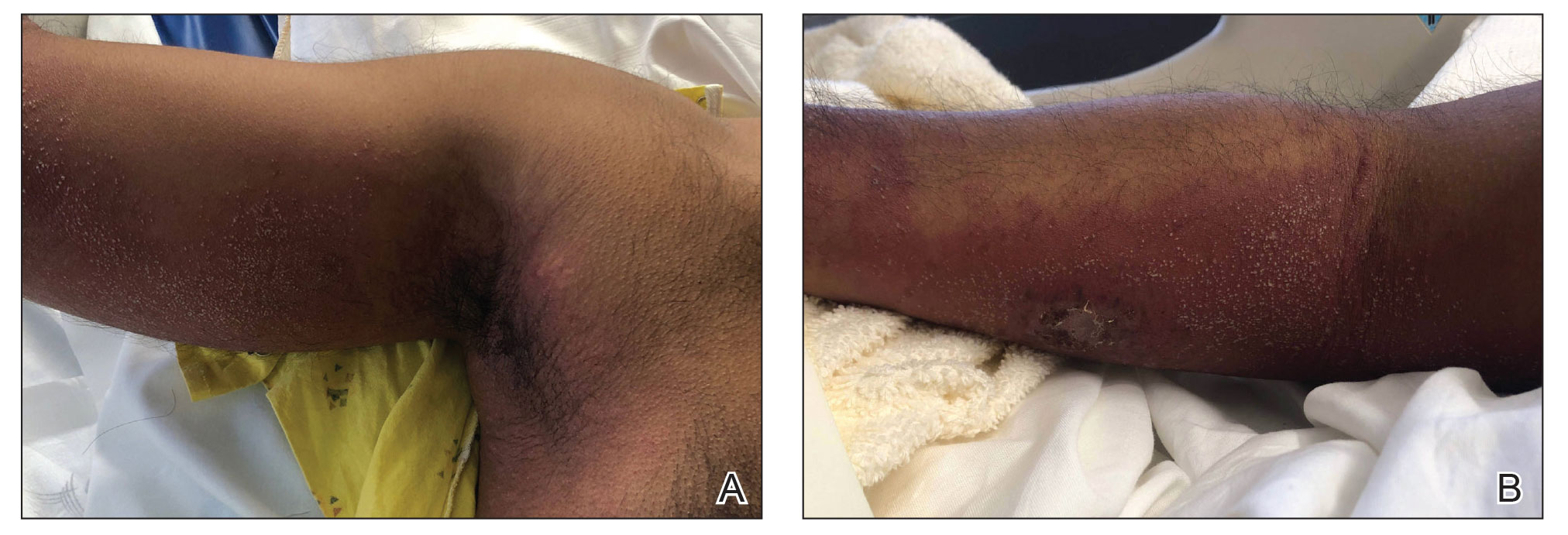

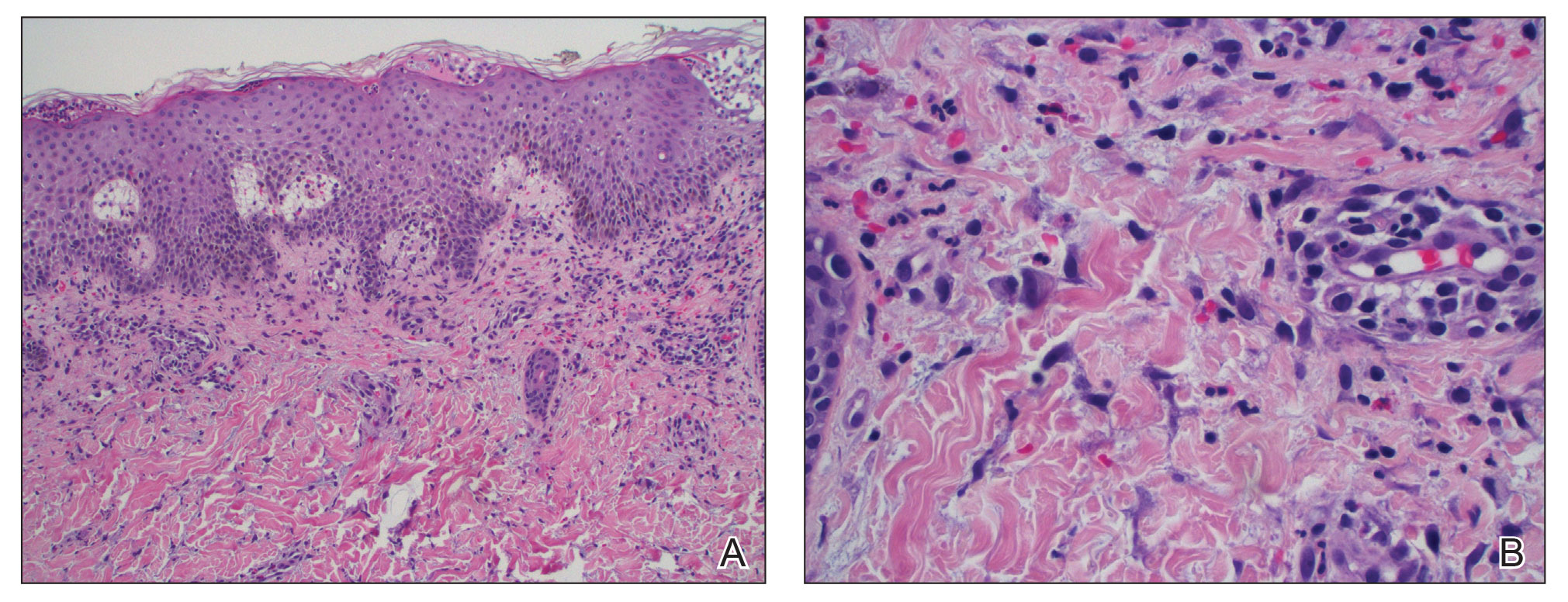

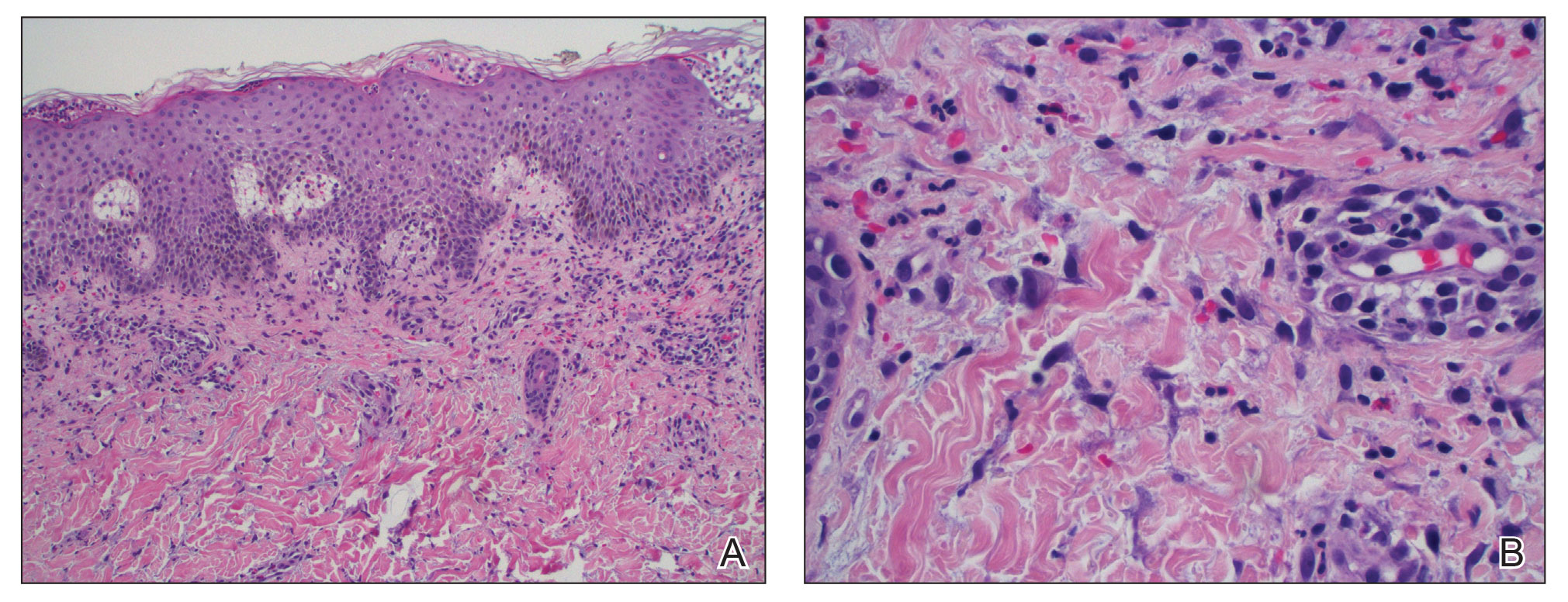

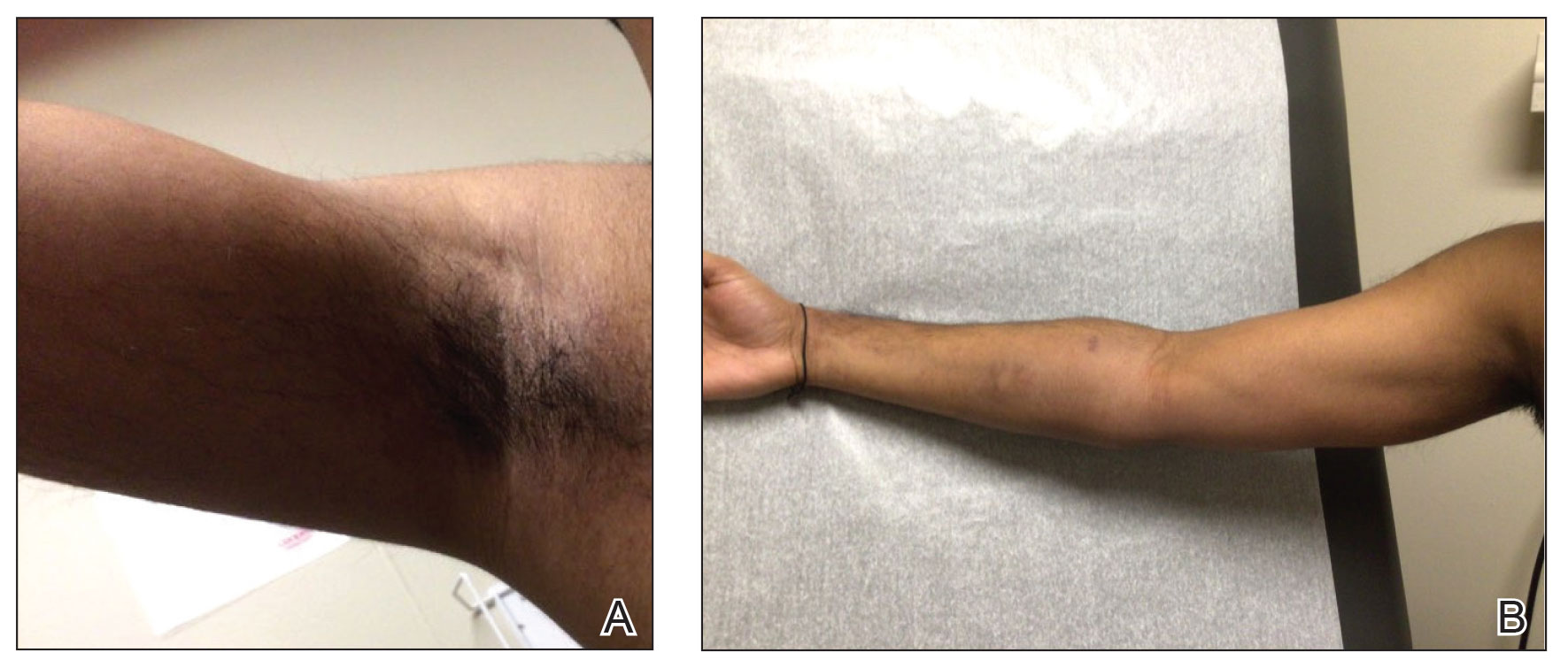

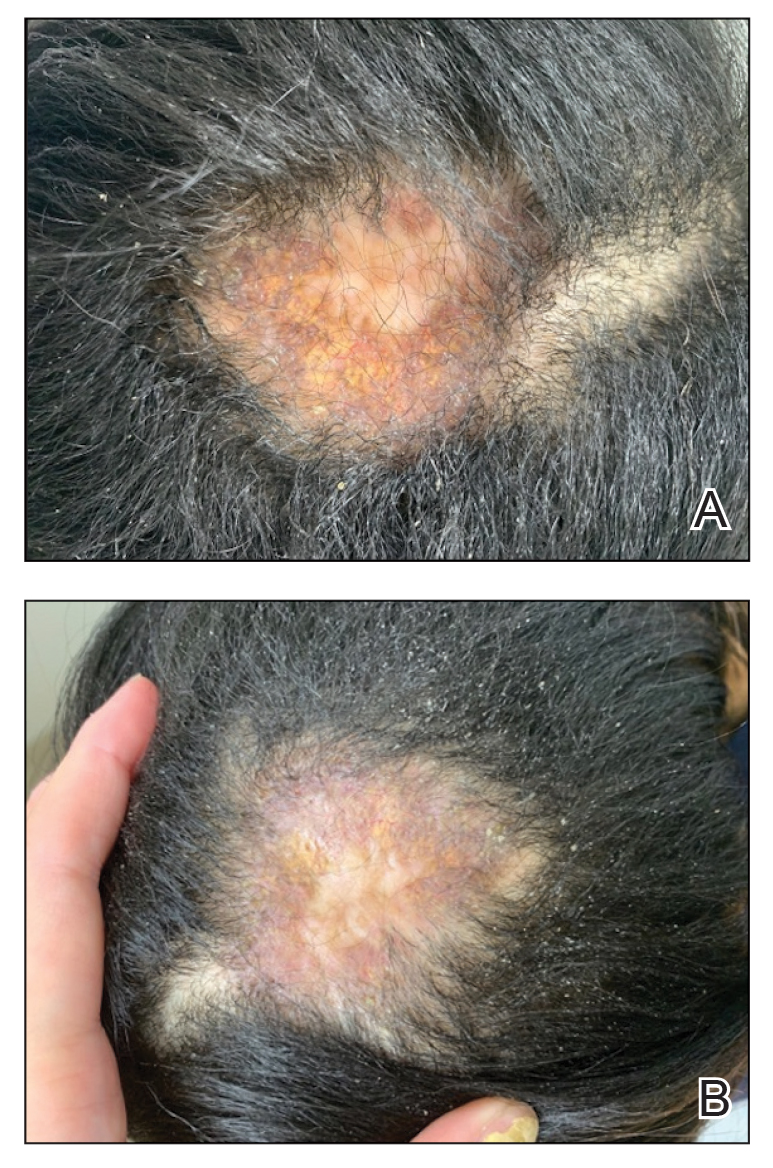

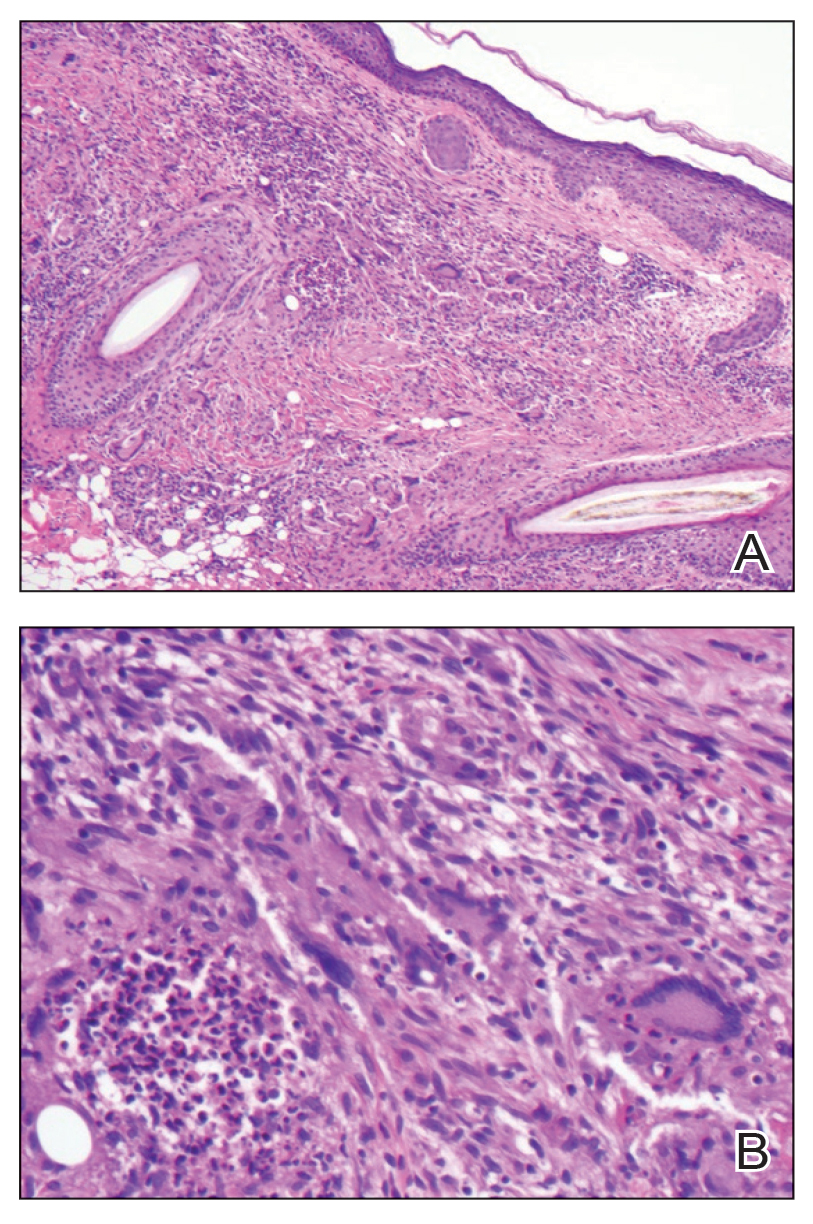

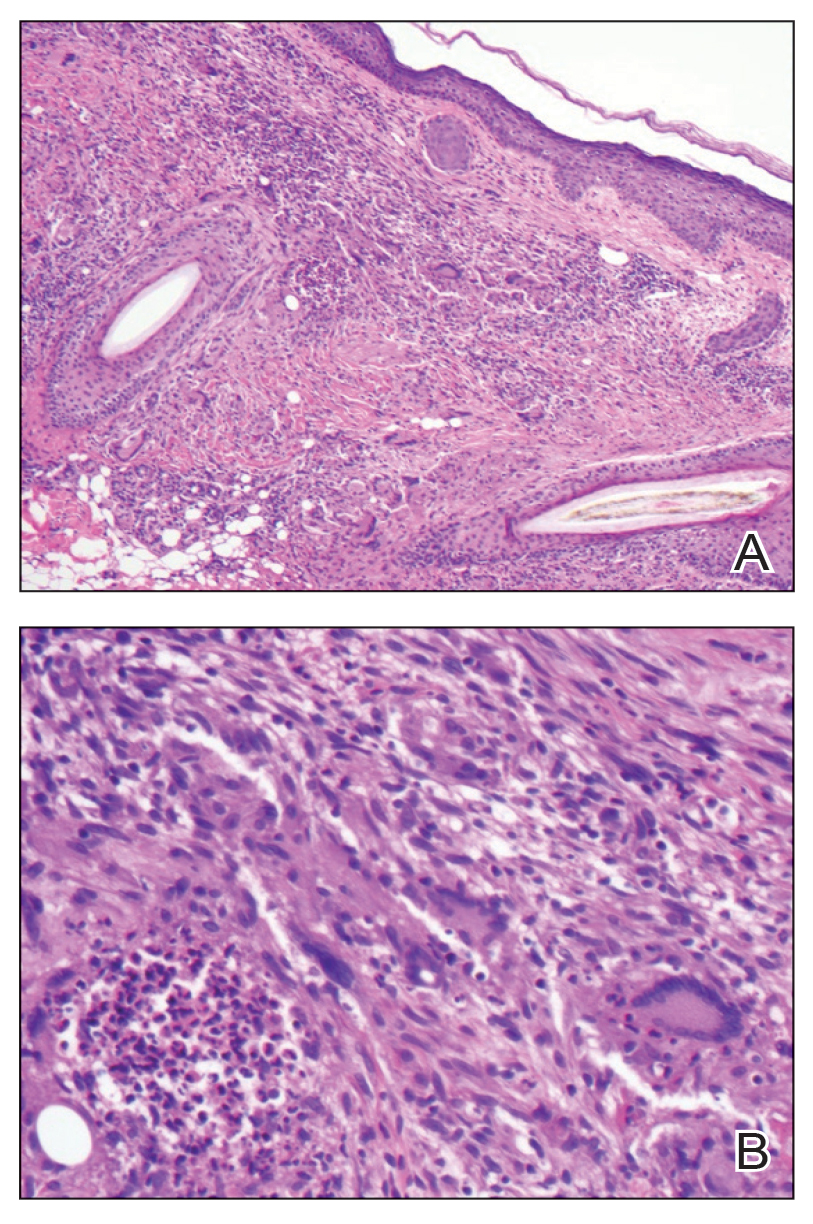

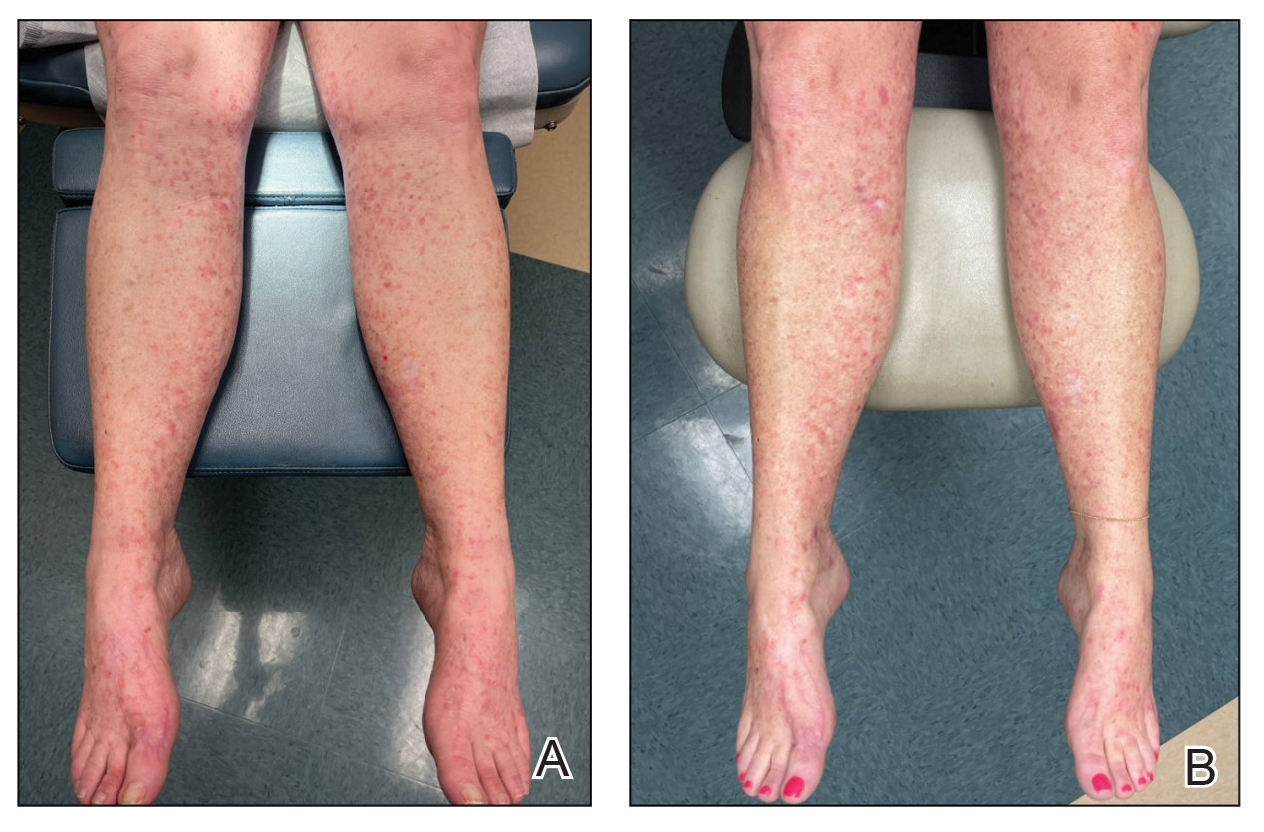

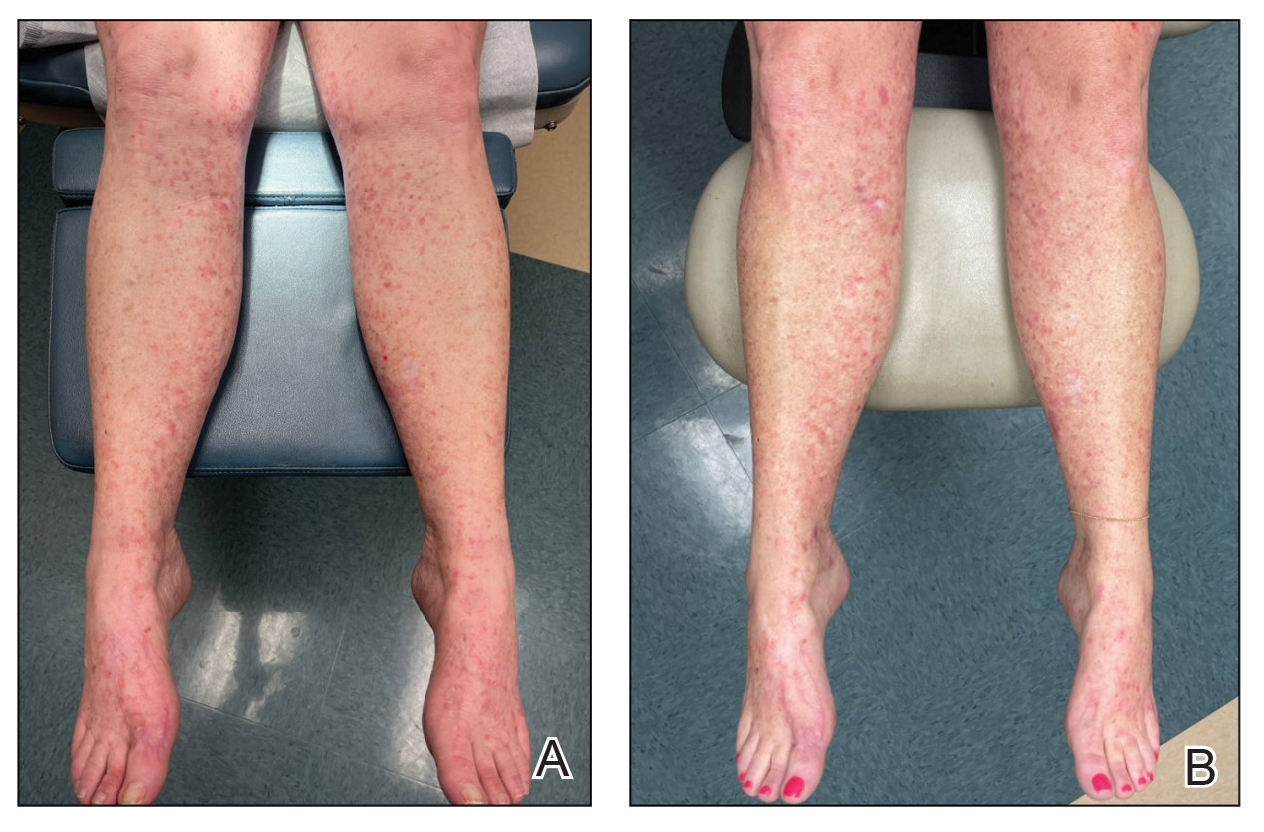

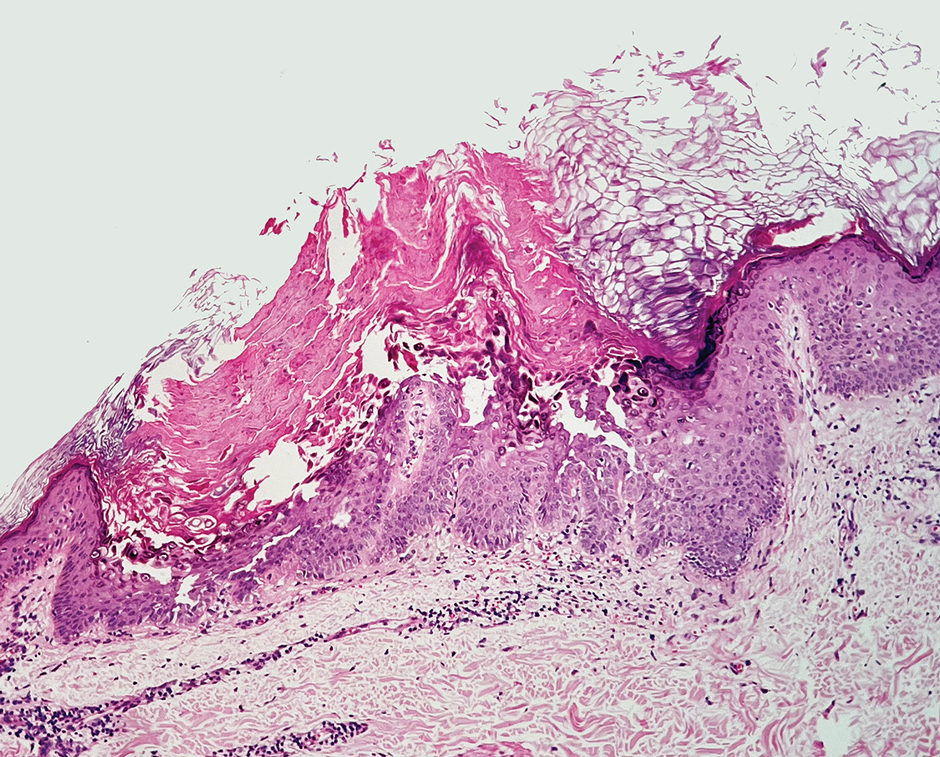

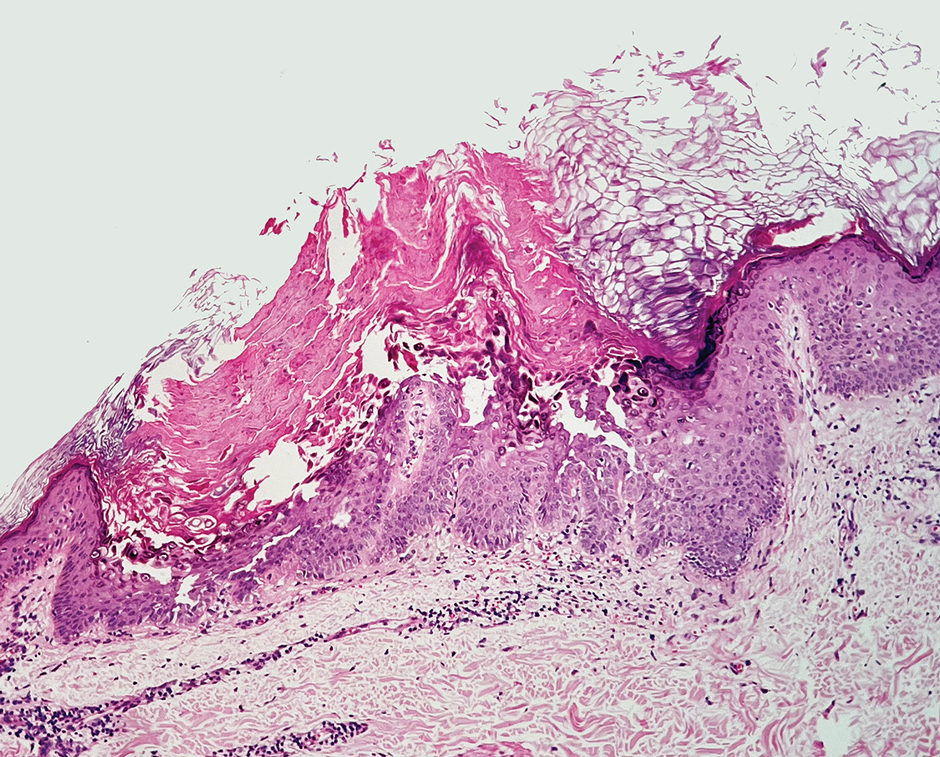

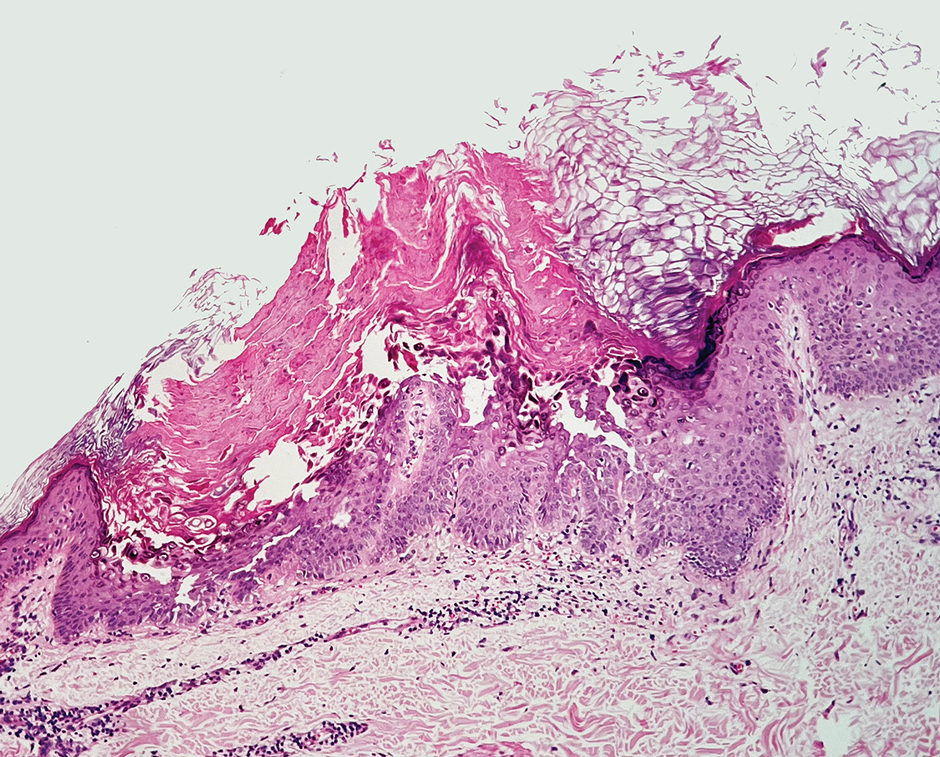

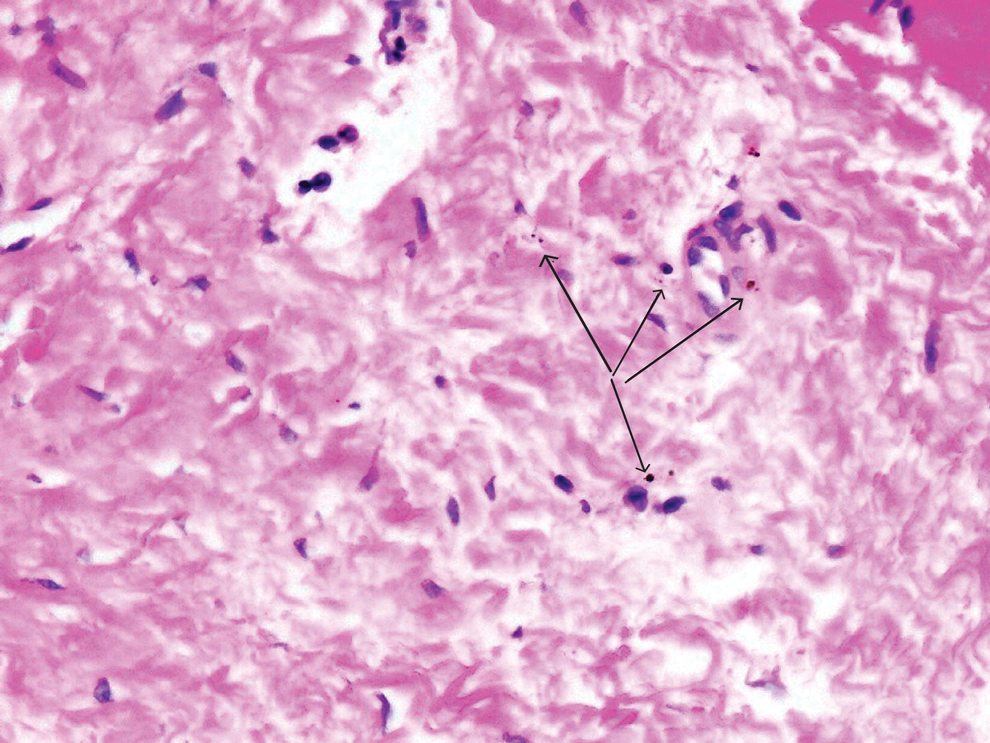

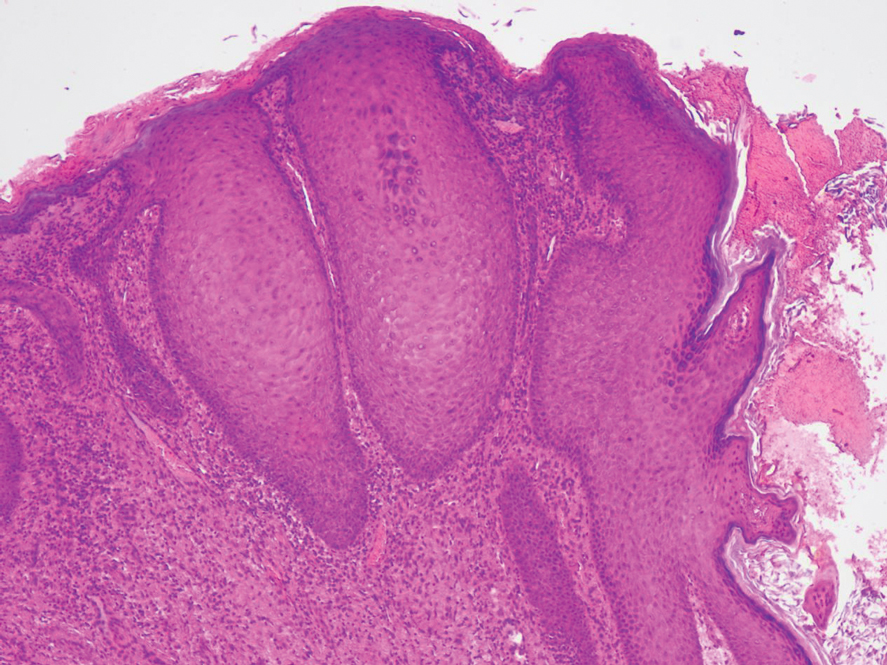

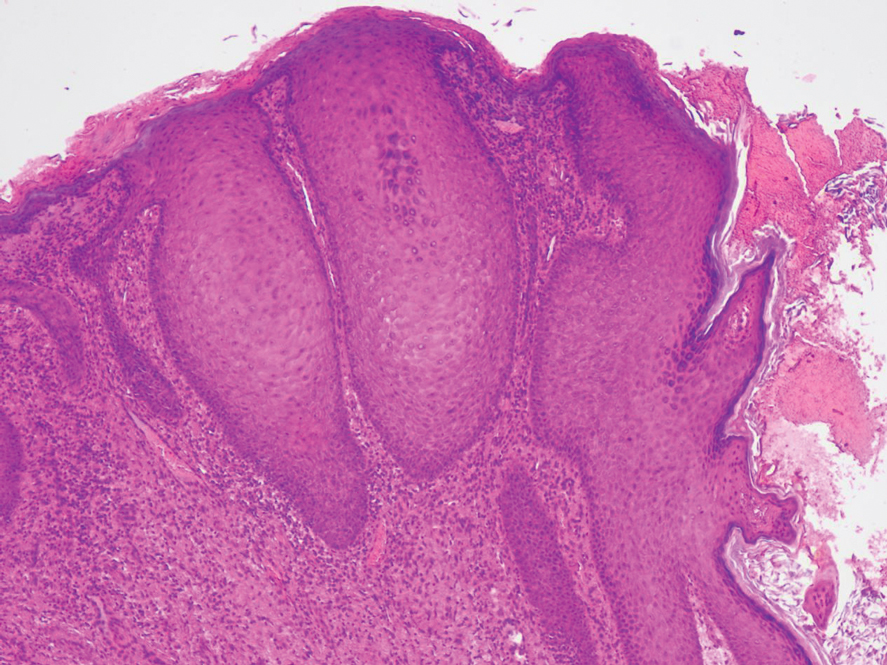

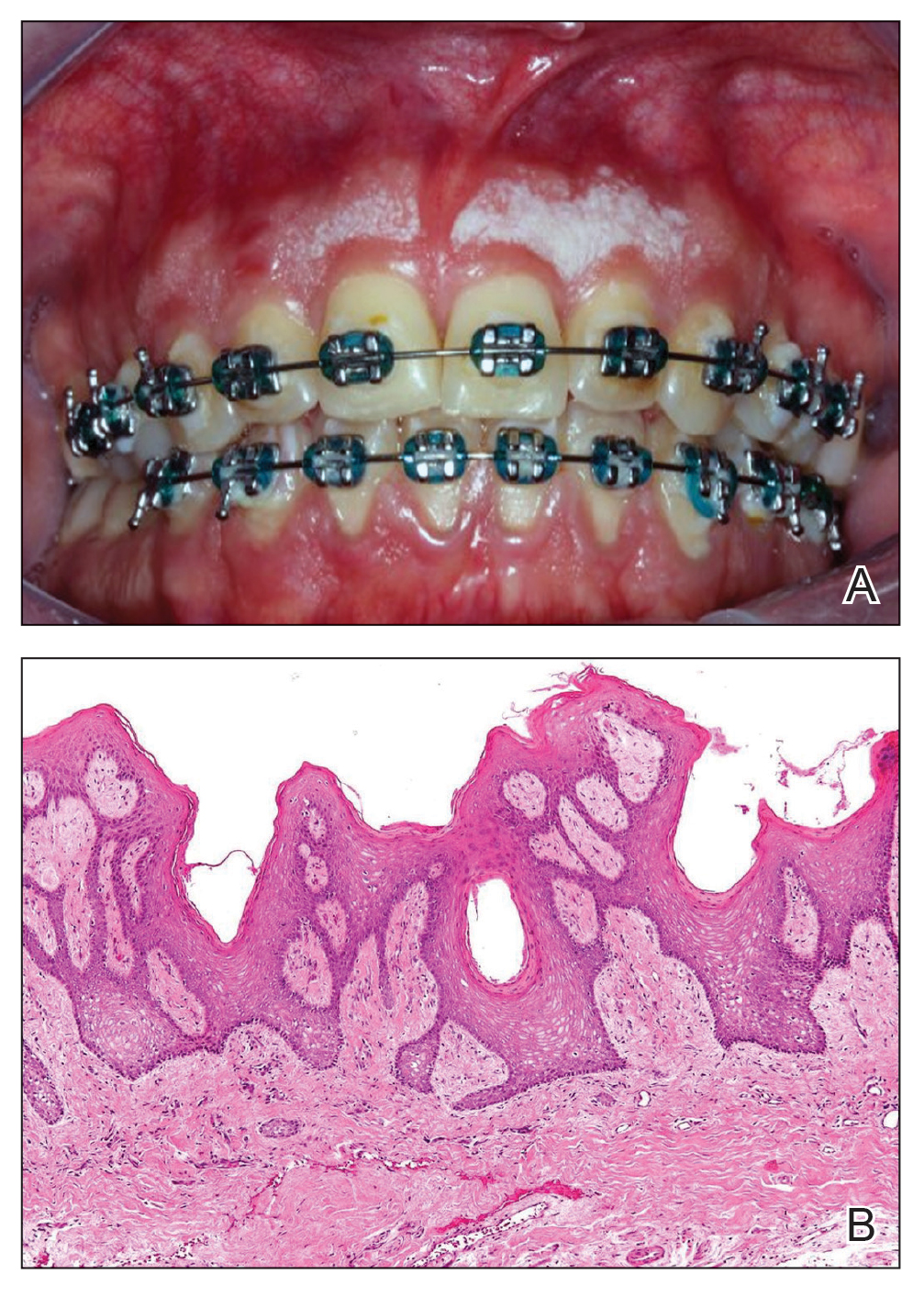

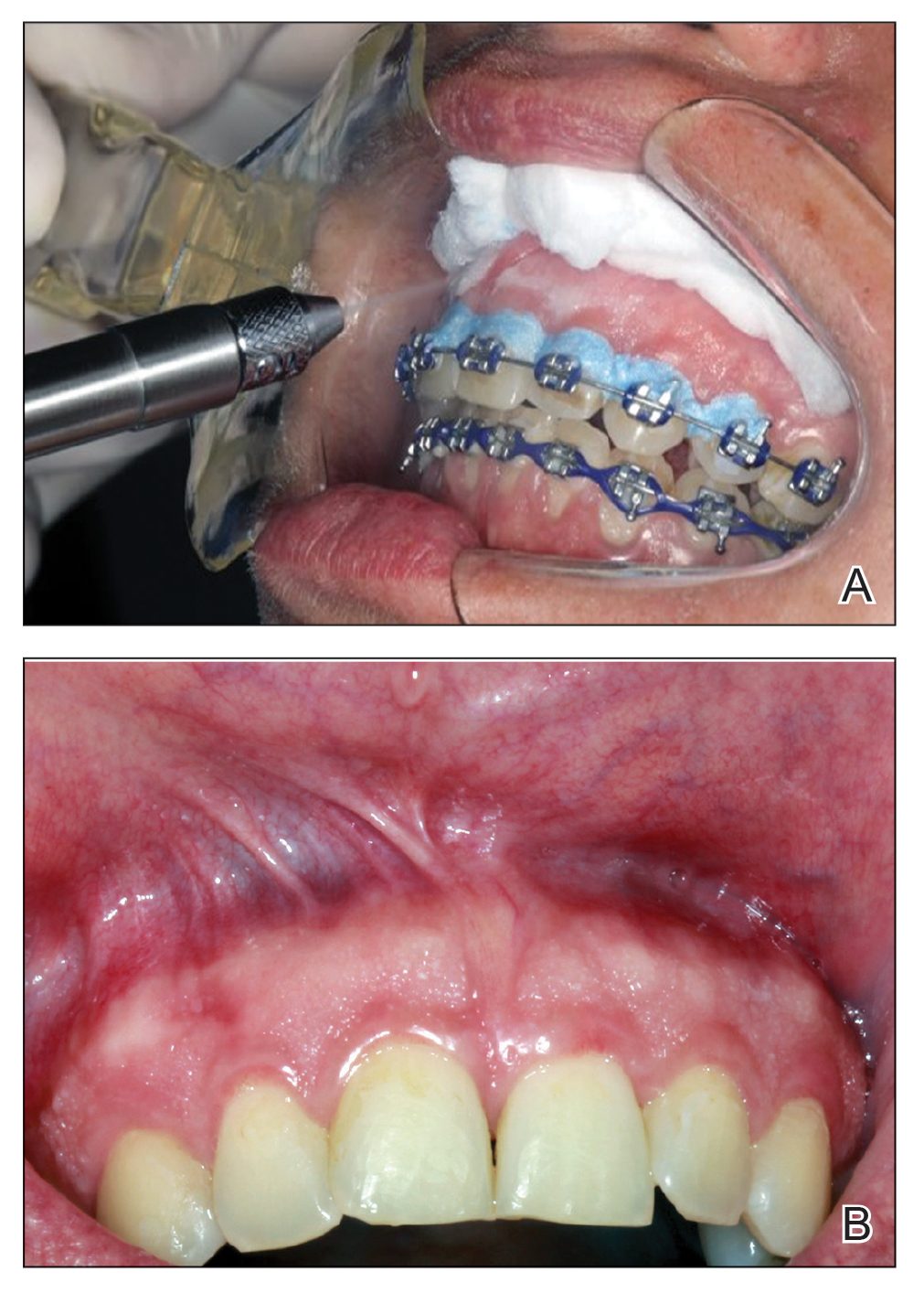

At presentation to our institution, the patient had widespread erythematous patches studded with pustules located on the arms, legs, and flexural areas as well as plaques of psoriasis involving approximately 20% of the body surface area (Figure 1). Furthermore, the patient was noted to have large noninflammatory bullae along the legs. The new eruption occurred on areas that were both treated and spared from the tapinarof cream 1%. Laboratory evaluation showed neutrophil-predominant leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 15.9×103/µL [reference range, 4.0-11.0×103/µL]; absolute neutrophil count, 10.3×103/µL [reference range, 1.5-8.0×103/µL]), absolute eosinophilia (1930/µL [reference range, 0-0.5×103/µL]), hypocalcemia (8.4 mg/dL [reference range, 8.5-10.5 mg/dL]), and a mild transaminitis (aspartate aminotransferase, 37 IU/L [reference range, 10-40 IU/L]; alanine aminotransferase, 53 IU/L [reference range, 7-56 U/L]). Histopathology demonstrated spongiosis with subcorneal and intraepidermal pustules and mixed dermal inflammation containing eosinophils (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence revealed mild granular staining of C3 at the basement membrane zone.

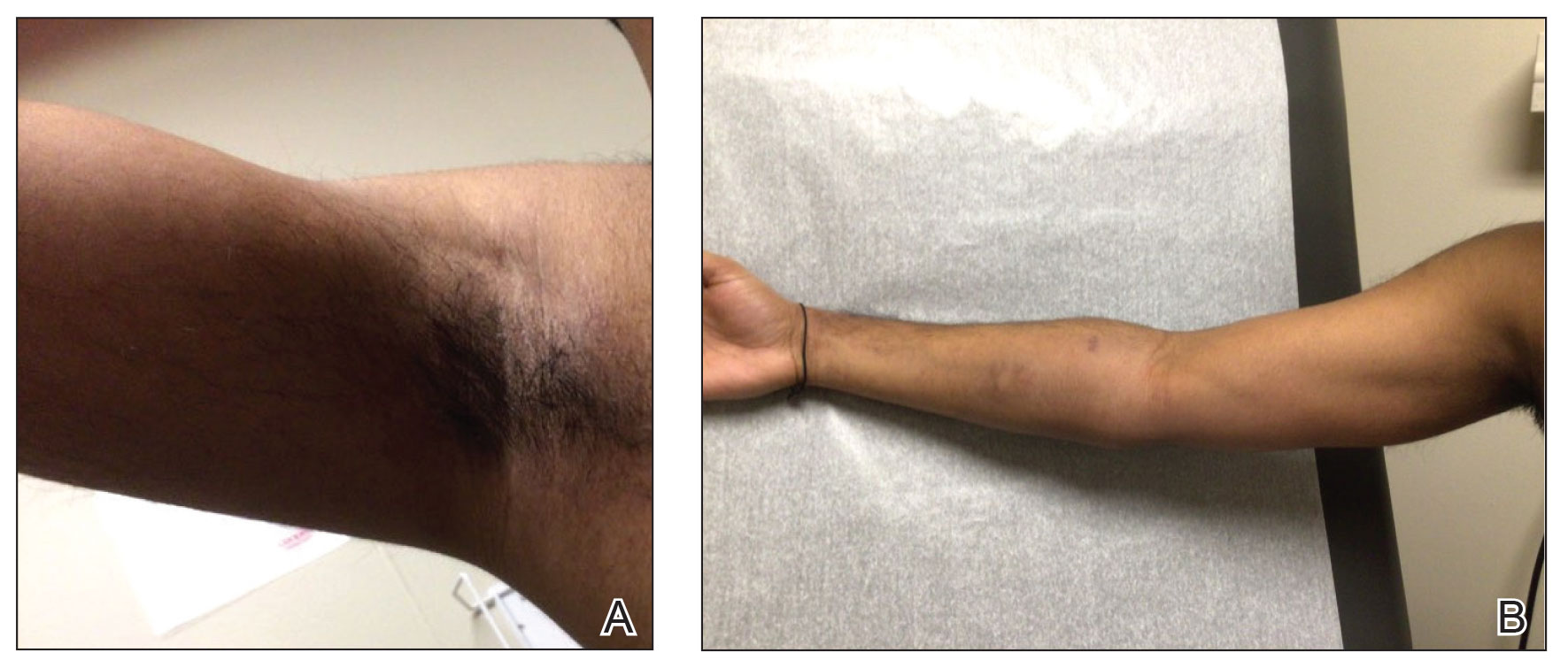

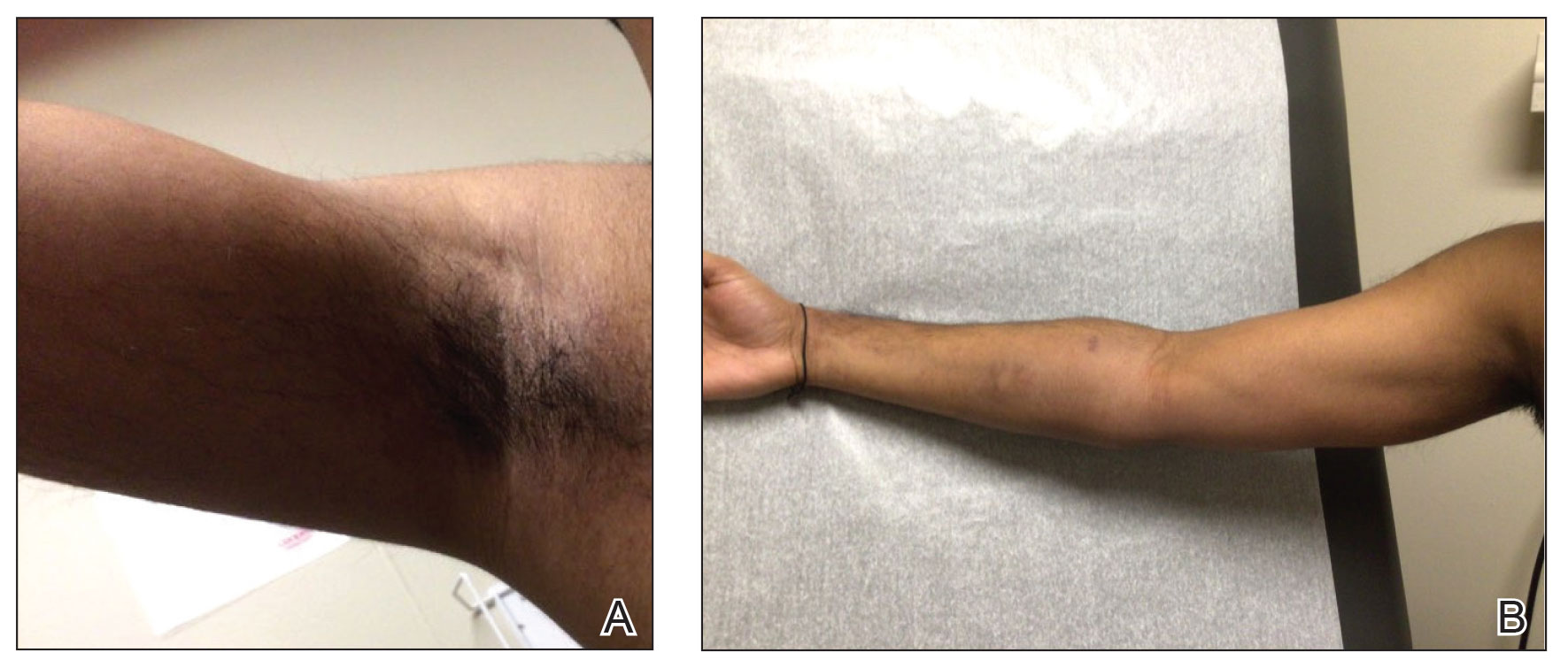

The patient was started on 1 mg/kg/d of prednisone tapered over 20 days, and he rapidly improved. Alanine aminotransferase levels peaked at 120 IU/L 2 weeks later. At that time, he had complete resolution of the original eruption and was transitioned to topical steroids for continued management of the psoriasis (Figure 3).

The differential diagnosis for our patient included AGEP, generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP), miliaria pustulosa, generalized cutaneous candidiasis, exuberant allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), and linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD). Based on the clinical manifestations, laboratory results, and histopathologic evaluation, we made the diagnosis of AGEP secondary to tapinarof with systemic absorption. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis has been reported with topical use of morphine and diphenhydramine, among other agents.4,5 To our knowledge, AGEP due to tapinarof cream 1% has not been reported. In the original clinical trials of tapinarof, folliculitis was contained to sites of application.2 Our patient developed pustules at sites distant to areas of application, as well as systemic symptoms and laboratory abnormalities, indicating a systemic reaction. It can be difficult to distinguish AGEP clinically and histologically from GPP. Both conditions can manifest with fever, hypocalcemia, and sterile pustules on a background of erythema that favors intertriginous areas.6 Infection, rapid oral steroid withdrawal, pregnancy, and rarely oral medications have been reported causes of GPP.6 Our patient did not have any of these exposures. There is overlap in the histology of AGEP and GPP. One retrospective series compared histologic samples to help distinguish these 2 entities. Reliable markers that favored AGEP over GPP included eosinophilic spongiosis, interface dermatitis, and dermal eosinophilia (>2/mm2).7 In contrast, the presence of CD161 positivity in the dermis with at least 10 cells favored a diagnosis of GPP.7 In our case, the presence of spongiosis with eosinophils in the dermis favored a diagnosis of AGEP over GPP.

Miliaria pustulosa is a benign condition caused by the occlusion of the epidermal portion of eccrine glands related to either high fever or hot and humid environmental conditions. While it can be present in intertriginous areas like AGEP, miliaria pustulosa can be seen extensively on the back, most commonly in immobile hospitalized patients.8 Generalized cutaneous candidiasis usually is caused by the yeast Candida albicans and can take on multiple morphologies, including folliculitis.9 The eruption may be disseminated but often is accentuated in intertriginous areas and the anogenital folds. Predisposing factors include immunosuppression, endocrinopathies, recent use of systemic antibiotics or steroids, chemotherapy, and indwelling catheters.9 Outside of recent antibiotic use, our patient did not have any risk factors for miliaria pustulosa, making this diagnosis unlikely.

Given the presence of overlapping bullae along the lower extremities, an exuberant ACD and LABD were considered. Bullae formation can occur in ACD secondary to robust inflammation and edema leading to acantholysis.10 While a delayed hypersensitivity reaction to topical tapinarof cream 1% was considered given that the patient used the medication for approximately 1 month prior to the onset of symptoms, it would be unlikely for ACD to present with a concomitant pustular eruption. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis is an autoimmune blistering disease in which antibodies target bullous pemphigoid antigen 2, and there is characteristically linear deposition of IgA at the dermal-epidermal junction that leads to subepidermal blistering.11 This often manifests clinically as widespread tense vesicles in an annular or string-of-pearls appearance. However, morphologies can vary, and large bullae may be seen. In adults, LABD typically is associated with inflammatory bowel disease, malignancy, or medications, notably vancomycin.11,12 Our patient did not have any of these predisposing factors, and his biopsy for direct immunofluorescence did not reveal the classic pattern described above.

Interestingly, there have been reports in the literature of bullous AGEP in the setting of oral anti-infectives. One report described a 62-year-old woman who developed widespread nonfollicular pustules with multiple tense serous blisters 24 hours after taking oral terbinafine.13 Another case described an 80-year-old woman with a similar presentation following a course of ciprofloxacin (although the timeline of medication administration was not described).14 In this case, patch testing to the culprit medication reproduced the response.14 In both cases, a biopsy revealed subcorneal and intraepidermal pustules with marked dermal edema.13,14 As previously described, spongiosis is a common feature of AGEP. We hypothesize that, similar to these reports, our patient had a robust inflammatory response leading to spongiosis, acantholysis, and blister formation secondary to AGEP.

Dermatologists should be aware of this case of AGEP secondary to tapinarof cream 1%, as reports in the literature are rare and it is a reminder that topical medications can cause serious systemic reactions.

- Lebwohl MG, Kircik LH, Moore AY, et al. Effect of roflumilast cream vs vehicle cream on chronic plaque psoriasis: the DERMIS-1 and DERMIS-2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA. 2022;328:1073-1084. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.15632

- Lebwohl MG, Stein Gold L, Strober B, et al. Phase 3 trials of tapinarof cream for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2219-2229. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2103629

- Szatkowski J, Schwartz RA. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP): a review and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:843-848. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.017

- Ghazawi FM, Colantonio S, Bradshaw S, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by topical morphine and confirmed by patch testing. Dermat Contact Atopic Occup Drug. 2020;31:E22-E23. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000573

- Hanafusa T, Igawa K, Azukizawa H, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by topical diphenhydramine. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21:994-995. doi:10.1684/ejd.2011.1500

- Reynolds KA, Pithadia DJ, Lee EB, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis: a review of the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations,diagnosis, and treatment. Cutis. 2022;110:19-25. doi:10.12788/cutis.0579

- Isom J, Braswell DS, Siroy A, et al. Clinical and histopathologic features differentiating acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis and pustular psoriasis: a retrospective series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:265-267. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.015

- Fealey RD, Hebert AA. Disorders of the eccrine sweat glands and sweating. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine.8th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2012:946.

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Marchiony Hunt K, et al. Fungal diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:1329-1363.

- Elmas ÖF, Akdeniz N, Atasoy M, et al. Contact dermatitis: a great imitator. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:176-192. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2019.10.003

- Hull CM, Zone JZ. Dermatitis herpetiforms and linear IgA bullous dermatosis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:527-537.

- Yamagami J, Nakamura Y, Nagao K, et al. Vancomycin mediates IgA autoreactivity in drug-induced linear IgA bullous dermatosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:1473-1480.

- Bullous acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis due to oral terbinafine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:P115. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.10.468

- Hausermann P, Scherer K, Weber M, et al. Ciprofloxacin-induced acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis mimicking bullous drug eruption confirmed by a positive patch test. Dermatology. 2005;211:277-280. doi:10.1159/000087024

To the Editor:

For many years, topical treatment of plaque psoriasis was limited to steroids, calcineurin inhibitors, vitamin D analogs, retinoids, coal tar products, and anthralin. In recent years, 2 new nonsteroidal treatment options with alternative mechanisms of action, roflumilast 0.3% and tapinarof 1%, have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.1 Roflumilast 0.3%, a topical phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, was shown in phase 3 clinical trials to reach an Investigator Global Assessment response of 37.5% to 42.2% in 8 weeks using once-daily application with minimal cutaneous adverse effects.1 Furthermore, it has demonstrated efficacy in treating psoriasis in intertriginous areas in subset analyses.1 Tapinarof is an aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist that suppresses Th17 cell differentiation by downregulating IL-17, IL-22, and IL-23.1 In phase 3 clinical trials, 35% to 40% of patients who used tapinarof cream 1% once daily demonstrated improvement in psoriasis compared with 6% who used the vehicle alone.2 In these studies, 18% to 24% of patients who used tapinarof cream 1% experienced folliculitis.2

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is a nonfollicular pustular drug reaction with systemic symptoms that typically occurs within 2 weeks of exposure to an inciting medication. Systemic antibiotics are the most commonly reported cause of AGEP.3 There are few reports in the literature of AGEP induced by topical agents.4,5 We report a case of AGEP in a young man following the use of tapinarof cream 1%.

A 23-year-old man with a history of psoriasis presented to the emergency department with fever and a pustular rash. One week prior to presentation, he developed a pustular eruption around plaques of psoriasis on the arms and legs. The patient had been prescribed tapinarof cream 1% by an outside dermatologist and was applying the medication to the affected areas once daily for 1 month prior to onset of symptoms. He discontinued tapinarof a few days prior to the eruption starting, but the rash progressed centrifugally and was associated with fevers and fatigue despite treatment with a brief course of empiric cephalexin prescribed by his primary care provider.

At presentation to our institution, the patient had widespread erythematous patches studded with pustules located on the arms, legs, and flexural areas as well as plaques of psoriasis involving approximately 20% of the body surface area (Figure 1). Furthermore, the patient was noted to have large noninflammatory bullae along the legs. The new eruption occurred on areas that were both treated and spared from the tapinarof cream 1%. Laboratory evaluation showed neutrophil-predominant leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 15.9×103/µL [reference range, 4.0-11.0×103/µL]; absolute neutrophil count, 10.3×103/µL [reference range, 1.5-8.0×103/µL]), absolute eosinophilia (1930/µL [reference range, 0-0.5×103/µL]), hypocalcemia (8.4 mg/dL [reference range, 8.5-10.5 mg/dL]), and a mild transaminitis (aspartate aminotransferase, 37 IU/L [reference range, 10-40 IU/L]; alanine aminotransferase, 53 IU/L [reference range, 7-56 U/L]). Histopathology demonstrated spongiosis with subcorneal and intraepidermal pustules and mixed dermal inflammation containing eosinophils (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence revealed mild granular staining of C3 at the basement membrane zone.

The patient was started on 1 mg/kg/d of prednisone tapered over 20 days, and he rapidly improved. Alanine aminotransferase levels peaked at 120 IU/L 2 weeks later. At that time, he had complete resolution of the original eruption and was transitioned to topical steroids for continued management of the psoriasis (Figure 3).

The differential diagnosis for our patient included AGEP, generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP), miliaria pustulosa, generalized cutaneous candidiasis, exuberant allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), and linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD). Based on the clinical manifestations, laboratory results, and histopathologic evaluation, we made the diagnosis of AGEP secondary to tapinarof with systemic absorption. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis has been reported with topical use of morphine and diphenhydramine, among other agents.4,5 To our knowledge, AGEP due to tapinarof cream 1% has not been reported. In the original clinical trials of tapinarof, folliculitis was contained to sites of application.2 Our patient developed pustules at sites distant to areas of application, as well as systemic symptoms and laboratory abnormalities, indicating a systemic reaction. It can be difficult to distinguish AGEP clinically and histologically from GPP. Both conditions can manifest with fever, hypocalcemia, and sterile pustules on a background of erythema that favors intertriginous areas.6 Infection, rapid oral steroid withdrawal, pregnancy, and rarely oral medications have been reported causes of GPP.6 Our patient did not have any of these exposures. There is overlap in the histology of AGEP and GPP. One retrospective series compared histologic samples to help distinguish these 2 entities. Reliable markers that favored AGEP over GPP included eosinophilic spongiosis, interface dermatitis, and dermal eosinophilia (>2/mm2).7 In contrast, the presence of CD161 positivity in the dermis with at least 10 cells favored a diagnosis of GPP.7 In our case, the presence of spongiosis with eosinophils in the dermis favored a diagnosis of AGEP over GPP.

Miliaria pustulosa is a benign condition caused by the occlusion of the epidermal portion of eccrine glands related to either high fever or hot and humid environmental conditions. While it can be present in intertriginous areas like AGEP, miliaria pustulosa can be seen extensively on the back, most commonly in immobile hospitalized patients.8 Generalized cutaneous candidiasis usually is caused by the yeast Candida albicans and can take on multiple morphologies, including folliculitis.9 The eruption may be disseminated but often is accentuated in intertriginous areas and the anogenital folds. Predisposing factors include immunosuppression, endocrinopathies, recent use of systemic antibiotics or steroids, chemotherapy, and indwelling catheters.9 Outside of recent antibiotic use, our patient did not have any risk factors for miliaria pustulosa, making this diagnosis unlikely.

Given the presence of overlapping bullae along the lower extremities, an exuberant ACD and LABD were considered. Bullae formation can occur in ACD secondary to robust inflammation and edema leading to acantholysis.10 While a delayed hypersensitivity reaction to topical tapinarof cream 1% was considered given that the patient used the medication for approximately 1 month prior to the onset of symptoms, it would be unlikely for ACD to present with a concomitant pustular eruption. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis is an autoimmune blistering disease in which antibodies target bullous pemphigoid antigen 2, and there is characteristically linear deposition of IgA at the dermal-epidermal junction that leads to subepidermal blistering.11 This often manifests clinically as widespread tense vesicles in an annular or string-of-pearls appearance. However, morphologies can vary, and large bullae may be seen. In adults, LABD typically is associated with inflammatory bowel disease, malignancy, or medications, notably vancomycin.11,12 Our patient did not have any of these predisposing factors, and his biopsy for direct immunofluorescence did not reveal the classic pattern described above.

Interestingly, there have been reports in the literature of bullous AGEP in the setting of oral anti-infectives. One report described a 62-year-old woman who developed widespread nonfollicular pustules with multiple tense serous blisters 24 hours after taking oral terbinafine.13 Another case described an 80-year-old woman with a similar presentation following a course of ciprofloxacin (although the timeline of medication administration was not described).14 In this case, patch testing to the culprit medication reproduced the response.14 In both cases, a biopsy revealed subcorneal and intraepidermal pustules with marked dermal edema.13,14 As previously described, spongiosis is a common feature of AGEP. We hypothesize that, similar to these reports, our patient had a robust inflammatory response leading to spongiosis, acantholysis, and blister formation secondary to AGEP.

Dermatologists should be aware of this case of AGEP secondary to tapinarof cream 1%, as reports in the literature are rare and it is a reminder that topical medications can cause serious systemic reactions.

To the Editor:

For many years, topical treatment of plaque psoriasis was limited to steroids, calcineurin inhibitors, vitamin D analogs, retinoids, coal tar products, and anthralin. In recent years, 2 new nonsteroidal treatment options with alternative mechanisms of action, roflumilast 0.3% and tapinarof 1%, have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.1 Roflumilast 0.3%, a topical phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, was shown in phase 3 clinical trials to reach an Investigator Global Assessment response of 37.5% to 42.2% in 8 weeks using once-daily application with minimal cutaneous adverse effects.1 Furthermore, it has demonstrated efficacy in treating psoriasis in intertriginous areas in subset analyses.1 Tapinarof is an aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist that suppresses Th17 cell differentiation by downregulating IL-17, IL-22, and IL-23.1 In phase 3 clinical trials, 35% to 40% of patients who used tapinarof cream 1% once daily demonstrated improvement in psoriasis compared with 6% who used the vehicle alone.2 In these studies, 18% to 24% of patients who used tapinarof cream 1% experienced folliculitis.2

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is a nonfollicular pustular drug reaction with systemic symptoms that typically occurs within 2 weeks of exposure to an inciting medication. Systemic antibiotics are the most commonly reported cause of AGEP.3 There are few reports in the literature of AGEP induced by topical agents.4,5 We report a case of AGEP in a young man following the use of tapinarof cream 1%.

A 23-year-old man with a history of psoriasis presented to the emergency department with fever and a pustular rash. One week prior to presentation, he developed a pustular eruption around plaques of psoriasis on the arms and legs. The patient had been prescribed tapinarof cream 1% by an outside dermatologist and was applying the medication to the affected areas once daily for 1 month prior to onset of symptoms. He discontinued tapinarof a few days prior to the eruption starting, but the rash progressed centrifugally and was associated with fevers and fatigue despite treatment with a brief course of empiric cephalexin prescribed by his primary care provider.

At presentation to our institution, the patient had widespread erythematous patches studded with pustules located on the arms, legs, and flexural areas as well as plaques of psoriasis involving approximately 20% of the body surface area (Figure 1). Furthermore, the patient was noted to have large noninflammatory bullae along the legs. The new eruption occurred on areas that were both treated and spared from the tapinarof cream 1%. Laboratory evaluation showed neutrophil-predominant leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 15.9×103/µL [reference range, 4.0-11.0×103/µL]; absolute neutrophil count, 10.3×103/µL [reference range, 1.5-8.0×103/µL]), absolute eosinophilia (1930/µL [reference range, 0-0.5×103/µL]), hypocalcemia (8.4 mg/dL [reference range, 8.5-10.5 mg/dL]), and a mild transaminitis (aspartate aminotransferase, 37 IU/L [reference range, 10-40 IU/L]; alanine aminotransferase, 53 IU/L [reference range, 7-56 U/L]). Histopathology demonstrated spongiosis with subcorneal and intraepidermal pustules and mixed dermal inflammation containing eosinophils (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence revealed mild granular staining of C3 at the basement membrane zone.

The patient was started on 1 mg/kg/d of prednisone tapered over 20 days, and he rapidly improved. Alanine aminotransferase levels peaked at 120 IU/L 2 weeks later. At that time, he had complete resolution of the original eruption and was transitioned to topical steroids for continued management of the psoriasis (Figure 3).

The differential diagnosis for our patient included AGEP, generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP), miliaria pustulosa, generalized cutaneous candidiasis, exuberant allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), and linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD). Based on the clinical manifestations, laboratory results, and histopathologic evaluation, we made the diagnosis of AGEP secondary to tapinarof with systemic absorption. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis has been reported with topical use of morphine and diphenhydramine, among other agents.4,5 To our knowledge, AGEP due to tapinarof cream 1% has not been reported. In the original clinical trials of tapinarof, folliculitis was contained to sites of application.2 Our patient developed pustules at sites distant to areas of application, as well as systemic symptoms and laboratory abnormalities, indicating a systemic reaction. It can be difficult to distinguish AGEP clinically and histologically from GPP. Both conditions can manifest with fever, hypocalcemia, and sterile pustules on a background of erythema that favors intertriginous areas.6 Infection, rapid oral steroid withdrawal, pregnancy, and rarely oral medications have been reported causes of GPP.6 Our patient did not have any of these exposures. There is overlap in the histology of AGEP and GPP. One retrospective series compared histologic samples to help distinguish these 2 entities. Reliable markers that favored AGEP over GPP included eosinophilic spongiosis, interface dermatitis, and dermal eosinophilia (>2/mm2).7 In contrast, the presence of CD161 positivity in the dermis with at least 10 cells favored a diagnosis of GPP.7 In our case, the presence of spongiosis with eosinophils in the dermis favored a diagnosis of AGEP over GPP.

Miliaria pustulosa is a benign condition caused by the occlusion of the epidermal portion of eccrine glands related to either high fever or hot and humid environmental conditions. While it can be present in intertriginous areas like AGEP, miliaria pustulosa can be seen extensively on the back, most commonly in immobile hospitalized patients.8 Generalized cutaneous candidiasis usually is caused by the yeast Candida albicans and can take on multiple morphologies, including folliculitis.9 The eruption may be disseminated but often is accentuated in intertriginous areas and the anogenital folds. Predisposing factors include immunosuppression, endocrinopathies, recent use of systemic antibiotics or steroids, chemotherapy, and indwelling catheters.9 Outside of recent antibiotic use, our patient did not have any risk factors for miliaria pustulosa, making this diagnosis unlikely.

Given the presence of overlapping bullae along the lower extremities, an exuberant ACD and LABD were considered. Bullae formation can occur in ACD secondary to robust inflammation and edema leading to acantholysis.10 While a delayed hypersensitivity reaction to topical tapinarof cream 1% was considered given that the patient used the medication for approximately 1 month prior to the onset of symptoms, it would be unlikely for ACD to present with a concomitant pustular eruption. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis is an autoimmune blistering disease in which antibodies target bullous pemphigoid antigen 2, and there is characteristically linear deposition of IgA at the dermal-epidermal junction that leads to subepidermal blistering.11 This often manifests clinically as widespread tense vesicles in an annular or string-of-pearls appearance. However, morphologies can vary, and large bullae may be seen. In adults, LABD typically is associated with inflammatory bowel disease, malignancy, or medications, notably vancomycin.11,12 Our patient did not have any of these predisposing factors, and his biopsy for direct immunofluorescence did not reveal the classic pattern described above.

Interestingly, there have been reports in the literature of bullous AGEP in the setting of oral anti-infectives. One report described a 62-year-old woman who developed widespread nonfollicular pustules with multiple tense serous blisters 24 hours after taking oral terbinafine.13 Another case described an 80-year-old woman with a similar presentation following a course of ciprofloxacin (although the timeline of medication administration was not described).14 In this case, patch testing to the culprit medication reproduced the response.14 In both cases, a biopsy revealed subcorneal and intraepidermal pustules with marked dermal edema.13,14 As previously described, spongiosis is a common feature of AGEP. We hypothesize that, similar to these reports, our patient had a robust inflammatory response leading to spongiosis, acantholysis, and blister formation secondary to AGEP.

Dermatologists should be aware of this case of AGEP secondary to tapinarof cream 1%, as reports in the literature are rare and it is a reminder that topical medications can cause serious systemic reactions.

- Lebwohl MG, Kircik LH, Moore AY, et al. Effect of roflumilast cream vs vehicle cream on chronic plaque psoriasis: the DERMIS-1 and DERMIS-2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA. 2022;328:1073-1084. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.15632

- Lebwohl MG, Stein Gold L, Strober B, et al. Phase 3 trials of tapinarof cream for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2219-2229. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2103629

- Szatkowski J, Schwartz RA. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP): a review and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:843-848. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.017

- Ghazawi FM, Colantonio S, Bradshaw S, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by topical morphine and confirmed by patch testing. Dermat Contact Atopic Occup Drug. 2020;31:E22-E23. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000573

- Hanafusa T, Igawa K, Azukizawa H, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by topical diphenhydramine. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21:994-995. doi:10.1684/ejd.2011.1500

- Reynolds KA, Pithadia DJ, Lee EB, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis: a review of the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations,diagnosis, and treatment. Cutis. 2022;110:19-25. doi:10.12788/cutis.0579

- Isom J, Braswell DS, Siroy A, et al. Clinical and histopathologic features differentiating acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis and pustular psoriasis: a retrospective series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:265-267. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.015

- Fealey RD, Hebert AA. Disorders of the eccrine sweat glands and sweating. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine.8th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2012:946.

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Marchiony Hunt K, et al. Fungal diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:1329-1363.

- Elmas ÖF, Akdeniz N, Atasoy M, et al. Contact dermatitis: a great imitator. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:176-192. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2019.10.003

- Hull CM, Zone JZ. Dermatitis herpetiforms and linear IgA bullous dermatosis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:527-537.

- Yamagami J, Nakamura Y, Nagao K, et al. Vancomycin mediates IgA autoreactivity in drug-induced linear IgA bullous dermatosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:1473-1480.

- Bullous acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis due to oral terbinafine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:P115. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.10.468

- Hausermann P, Scherer K, Weber M, et al. Ciprofloxacin-induced acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis mimicking bullous drug eruption confirmed by a positive patch test. Dermatology. 2005;211:277-280. doi:10.1159/000087024

- Lebwohl MG, Kircik LH, Moore AY, et al. Effect of roflumilast cream vs vehicle cream on chronic plaque psoriasis: the DERMIS-1 and DERMIS-2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA. 2022;328:1073-1084. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.15632

- Lebwohl MG, Stein Gold L, Strober B, et al. Phase 3 trials of tapinarof cream for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2219-2229. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2103629

- Szatkowski J, Schwartz RA. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP): a review and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:843-848. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.017

- Ghazawi FM, Colantonio S, Bradshaw S, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by topical morphine and confirmed by patch testing. Dermat Contact Atopic Occup Drug. 2020;31:E22-E23. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000573

- Hanafusa T, Igawa K, Azukizawa H, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by topical diphenhydramine. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21:994-995. doi:10.1684/ejd.2011.1500

- Reynolds KA, Pithadia DJ, Lee EB, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis: a review of the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations,diagnosis, and treatment. Cutis. 2022;110:19-25. doi:10.12788/cutis.0579

- Isom J, Braswell DS, Siroy A, et al. Clinical and histopathologic features differentiating acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis and pustular psoriasis: a retrospective series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:265-267. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.015

- Fealey RD, Hebert AA. Disorders of the eccrine sweat glands and sweating. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine.8th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2012:946.

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Marchiony Hunt K, et al. Fungal diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:1329-1363.

- Elmas ÖF, Akdeniz N, Atasoy M, et al. Contact dermatitis: a great imitator. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:176-192. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2019.10.003

- Hull CM, Zone JZ. Dermatitis herpetiforms and linear IgA bullous dermatosis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:527-537.

- Yamagami J, Nakamura Y, Nagao K, et al. Vancomycin mediates IgA autoreactivity in drug-induced linear IgA bullous dermatosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:1473-1480.

- Bullous acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis due to oral terbinafine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:P115. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.10.468

- Hausermann P, Scherer K, Weber M, et al. Ciprofloxacin-induced acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis mimicking bullous drug eruption confirmed by a positive patch test. Dermatology. 2005;211:277-280. doi:10.1159/000087024

Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis Secondary to Application of Tapinarof Cream 1%

Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis Secondary to Application of Tapinarof Cream 1%

PRACTICE POINTS

- Tapinarof cream 1% can be absorbed systemically and cause acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP).

- Clinical configuration and histology can be useful to distinguish AGEP from mimickers.

- Topical application of drugs in general, particularly over large body surface areas, may lead to systemic drug eruptions.

Rare Case of Necrobiotic Xanthogranuloma on the Scalp

Rare Case of Necrobiotic Xanthogranuloma on the Scalp

To the Editor:

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma (NXG) is classified as a cutaneous non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis, often seen with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance or multiple myeloma.1 Clinically, it appears as a red or yellow plaque with occasional ulceration and telangiectasias, most commonly seen periorbitally and on the trunk. On pathology, NXG appears as necrobiosis, giant cells, and various inflammatory cells extending into the subcutaneous tissue.2 In this article, we describe a rare presentation of NXG in location and skin type.

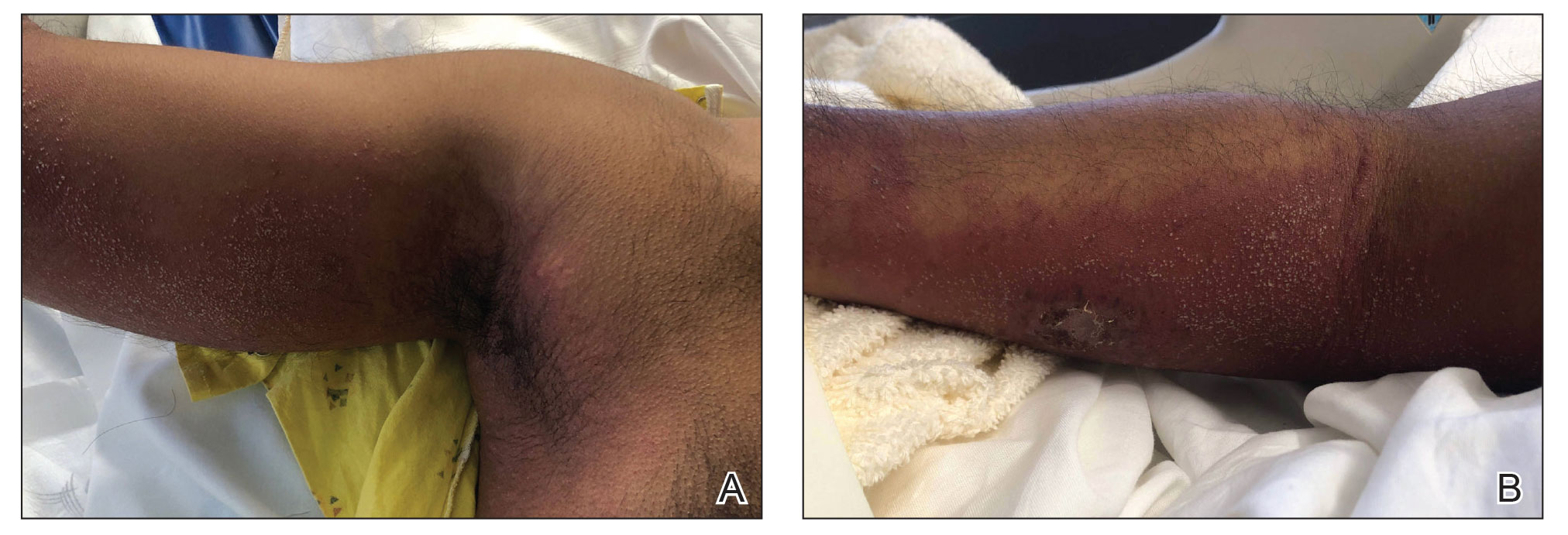

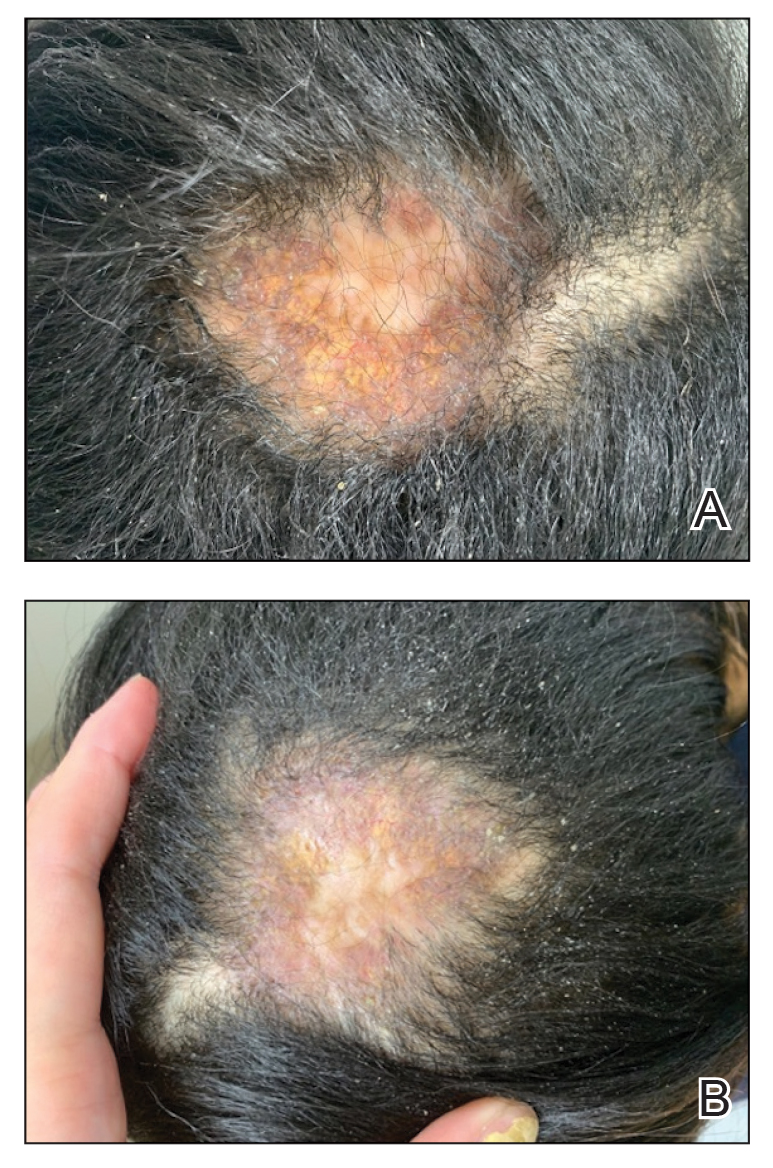

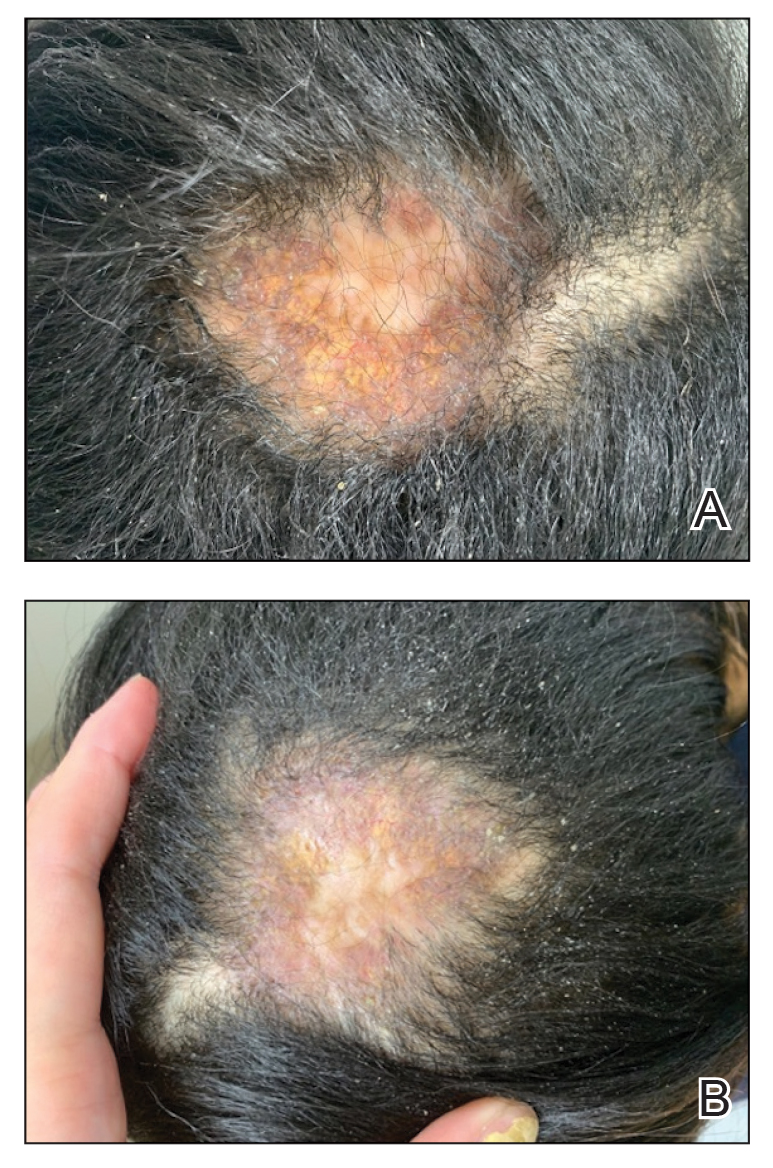

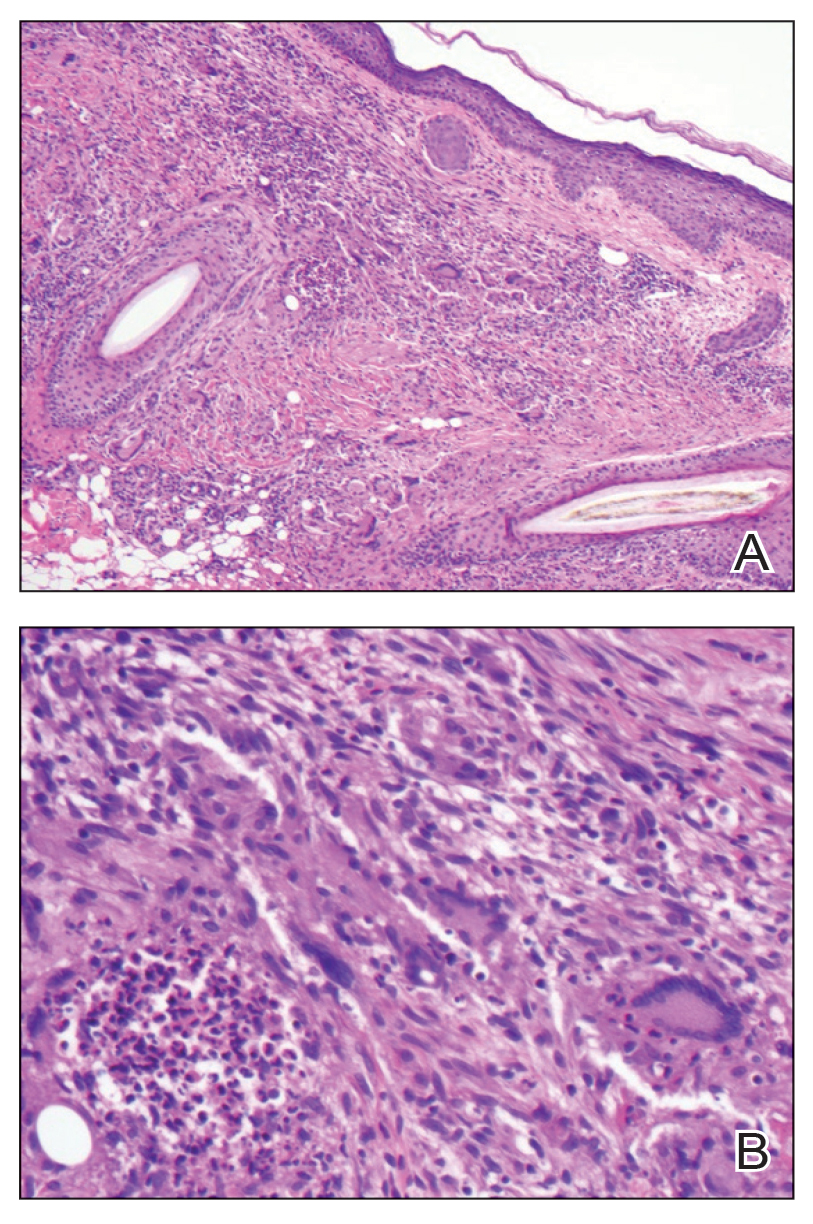

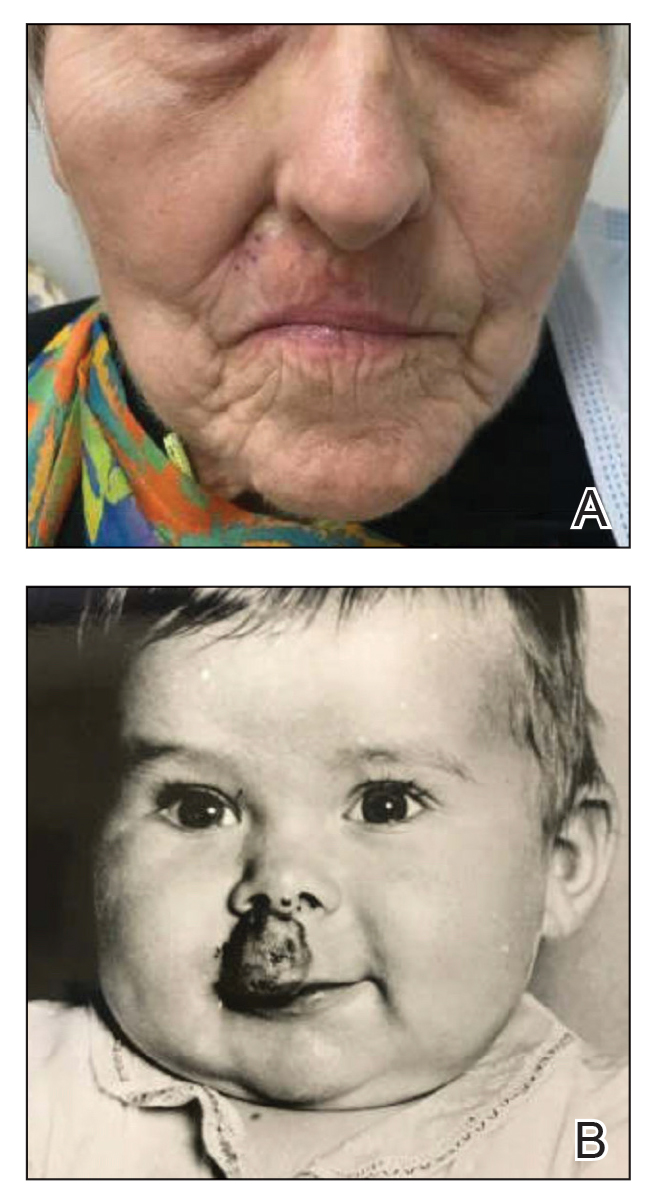

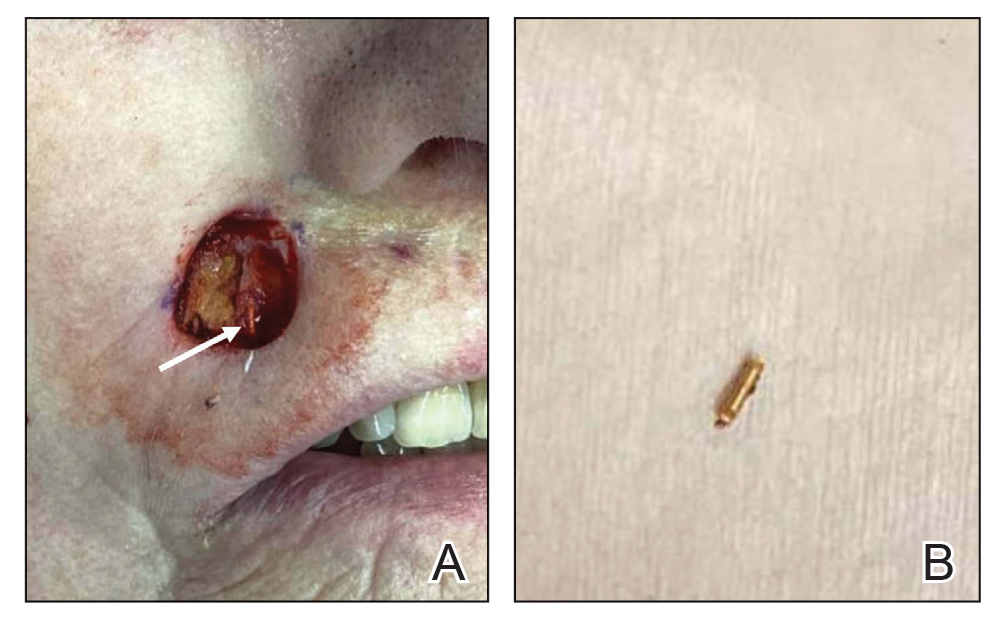

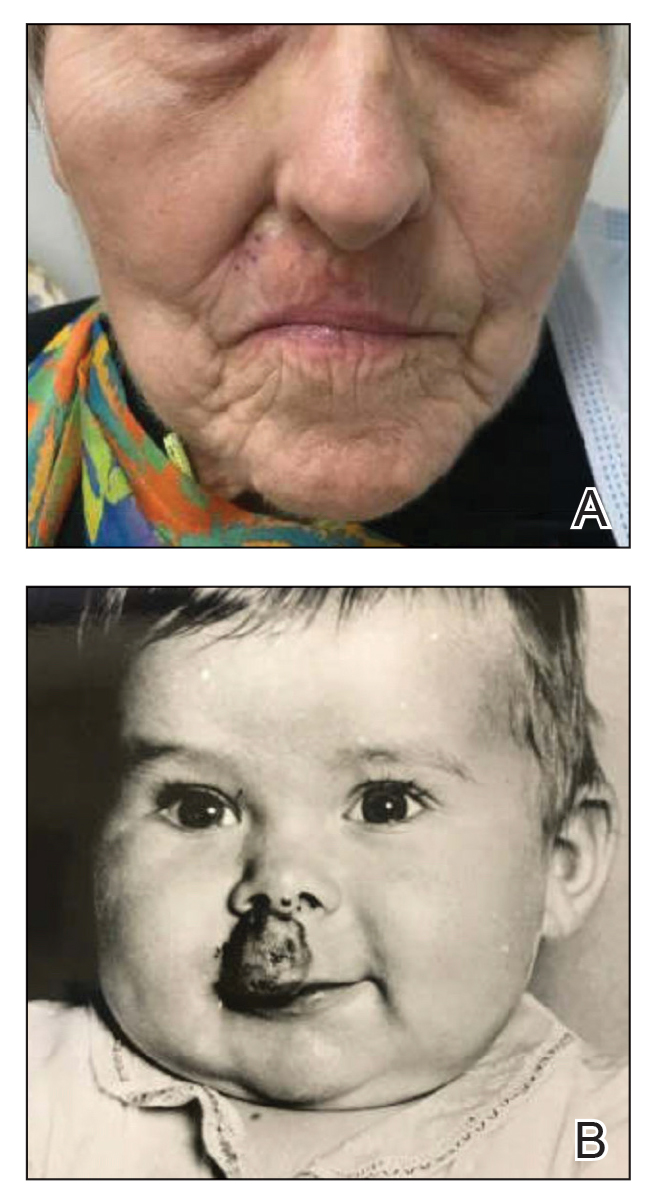

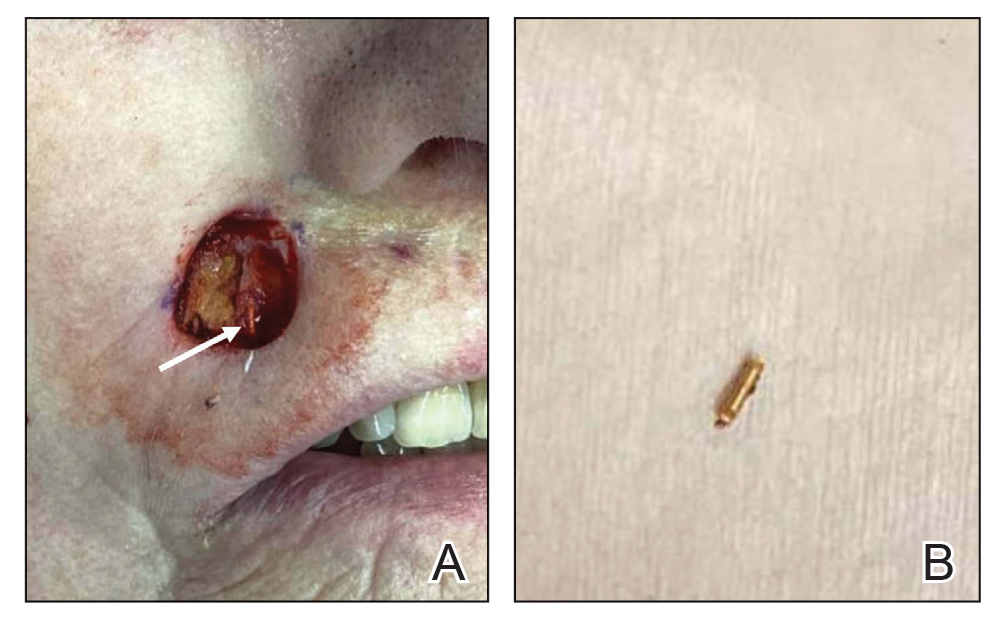

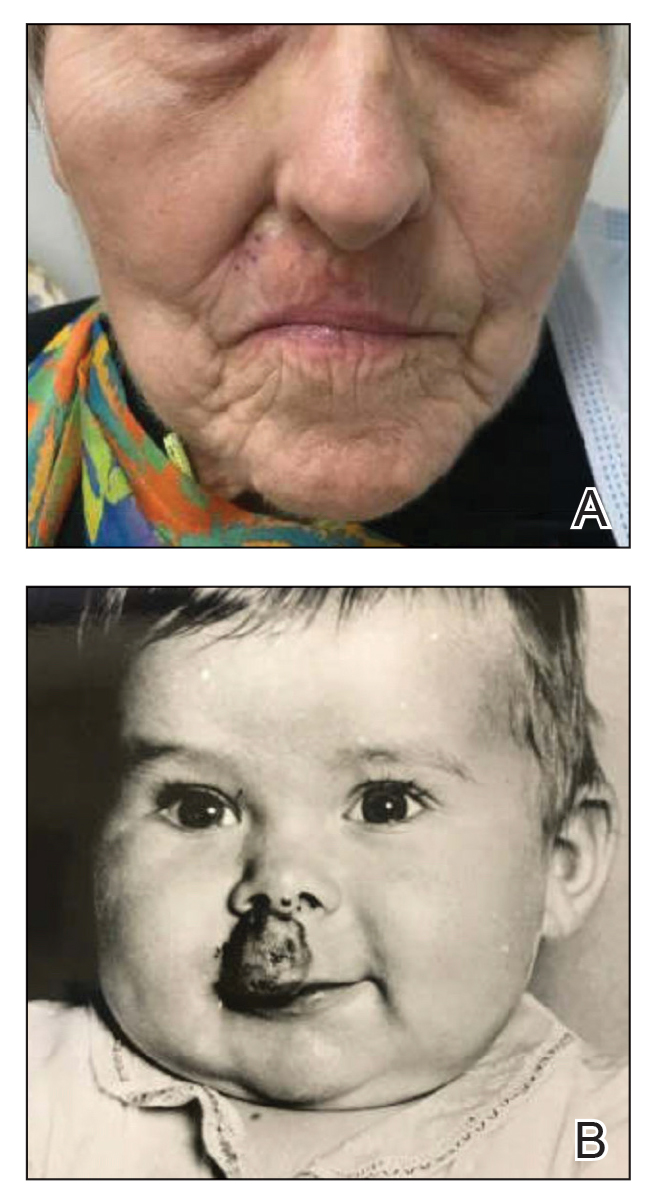

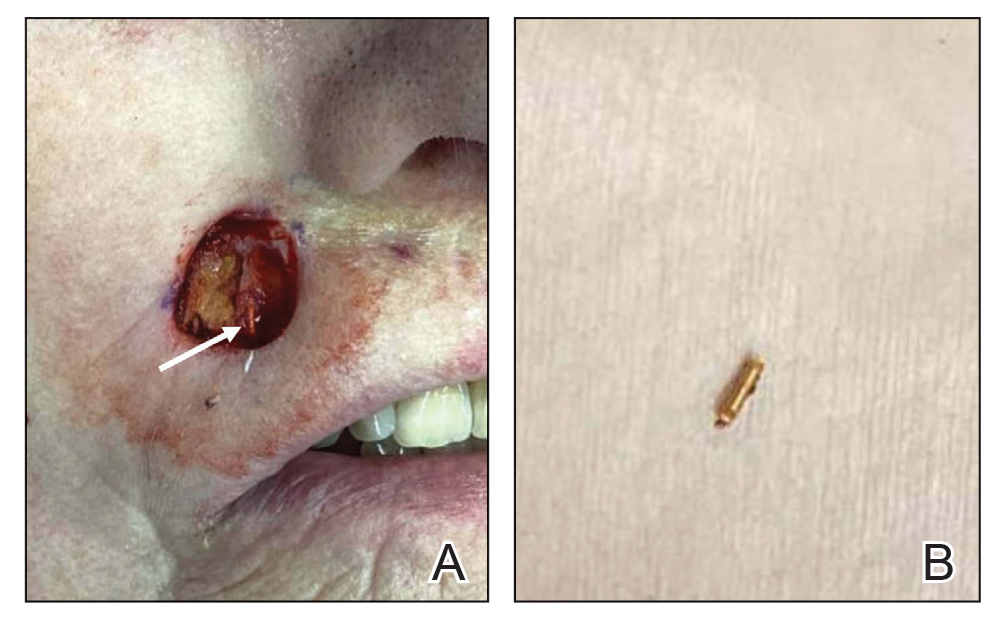

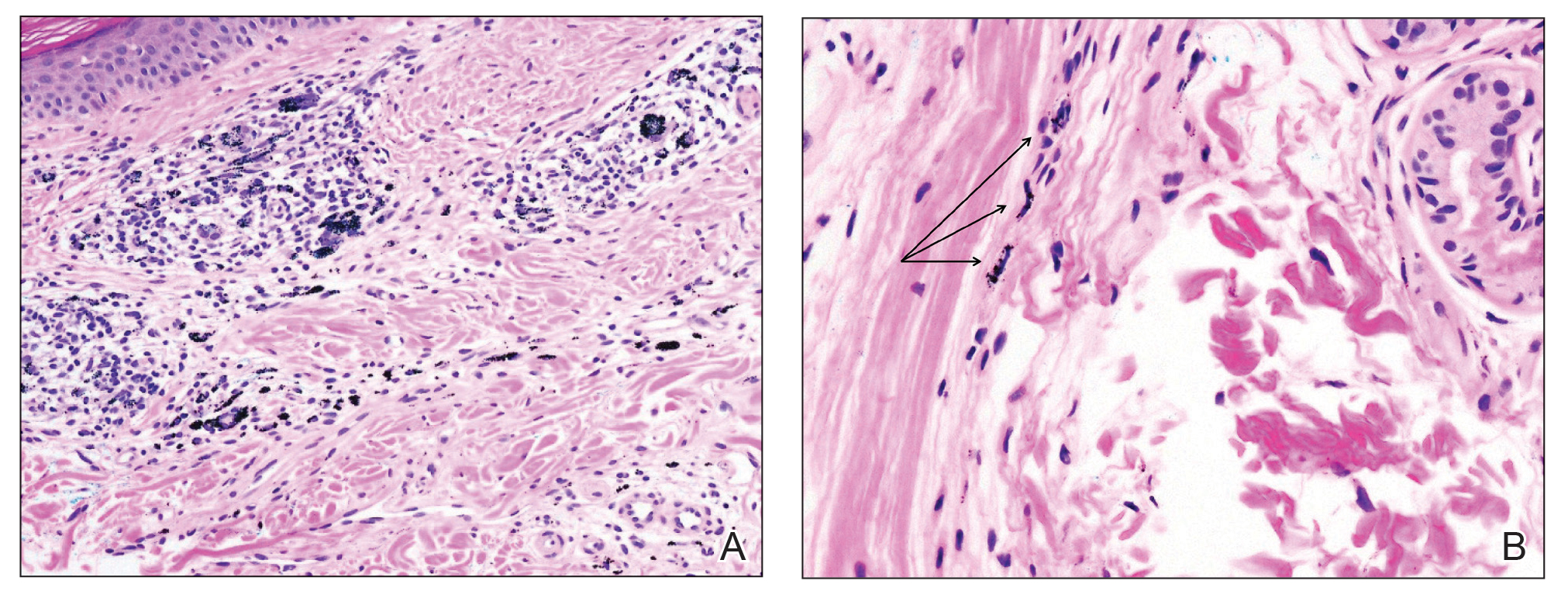

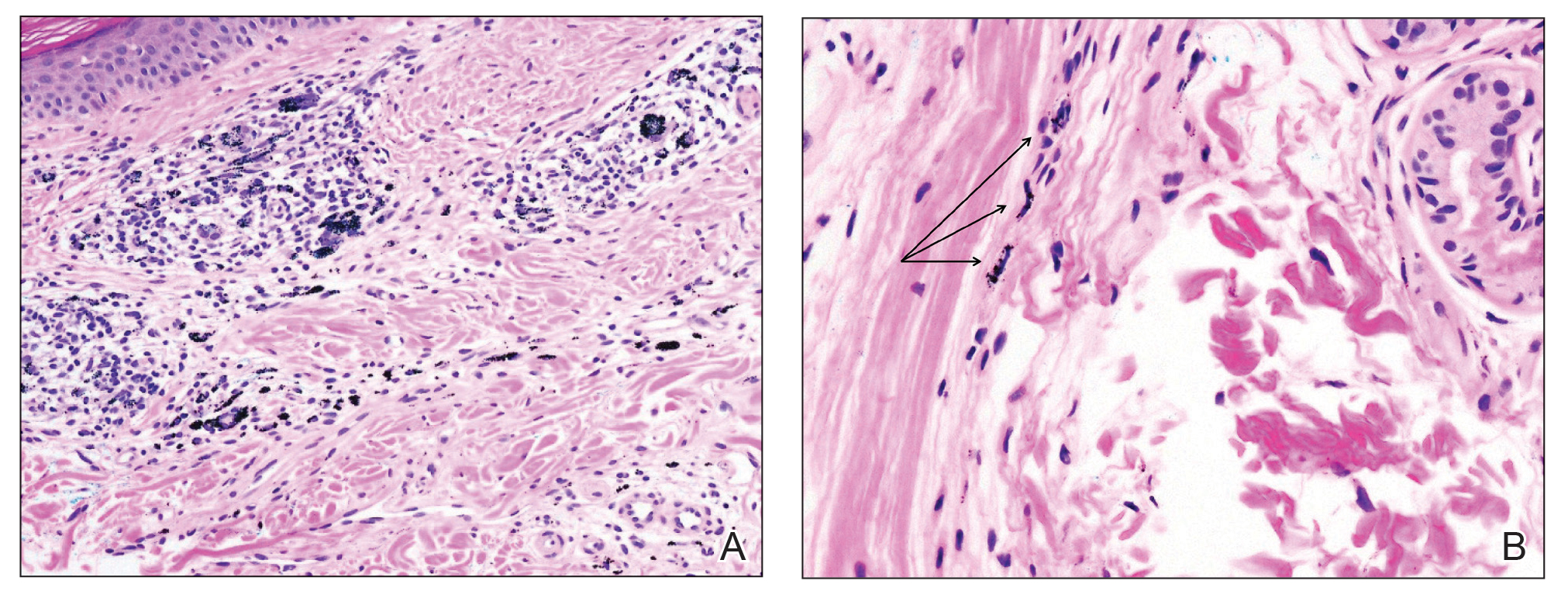

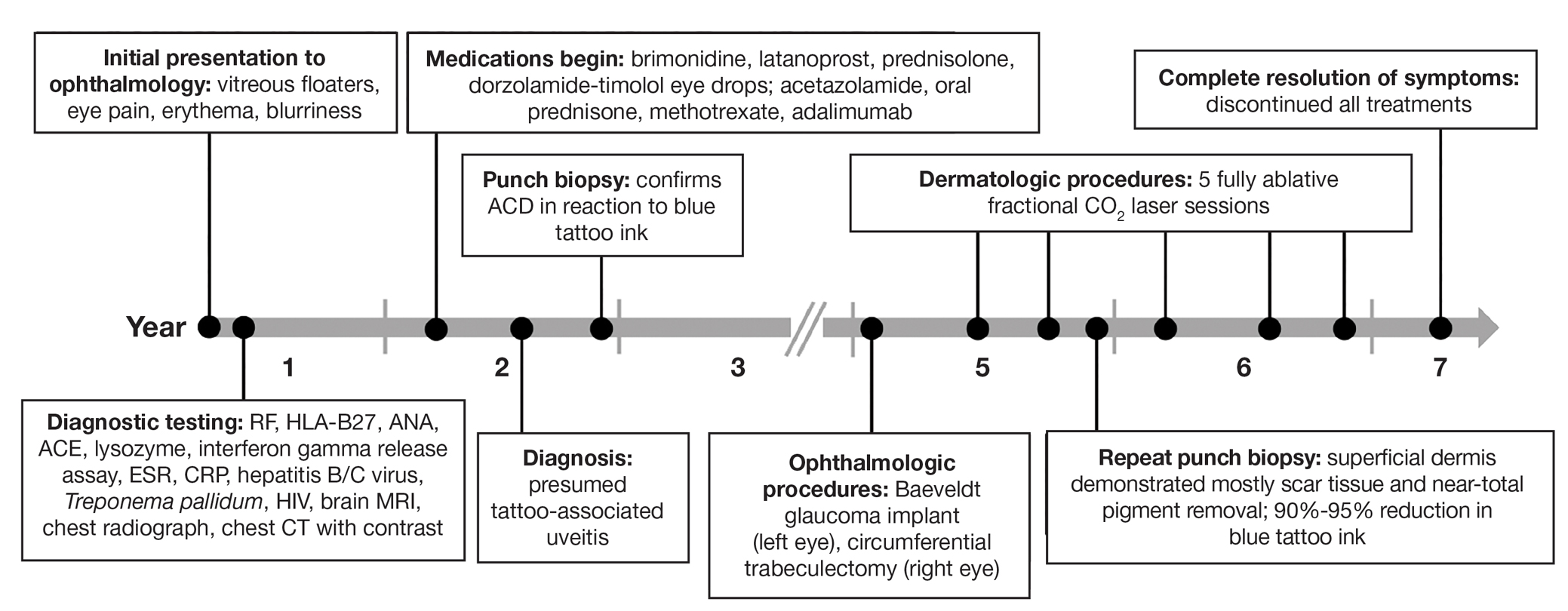

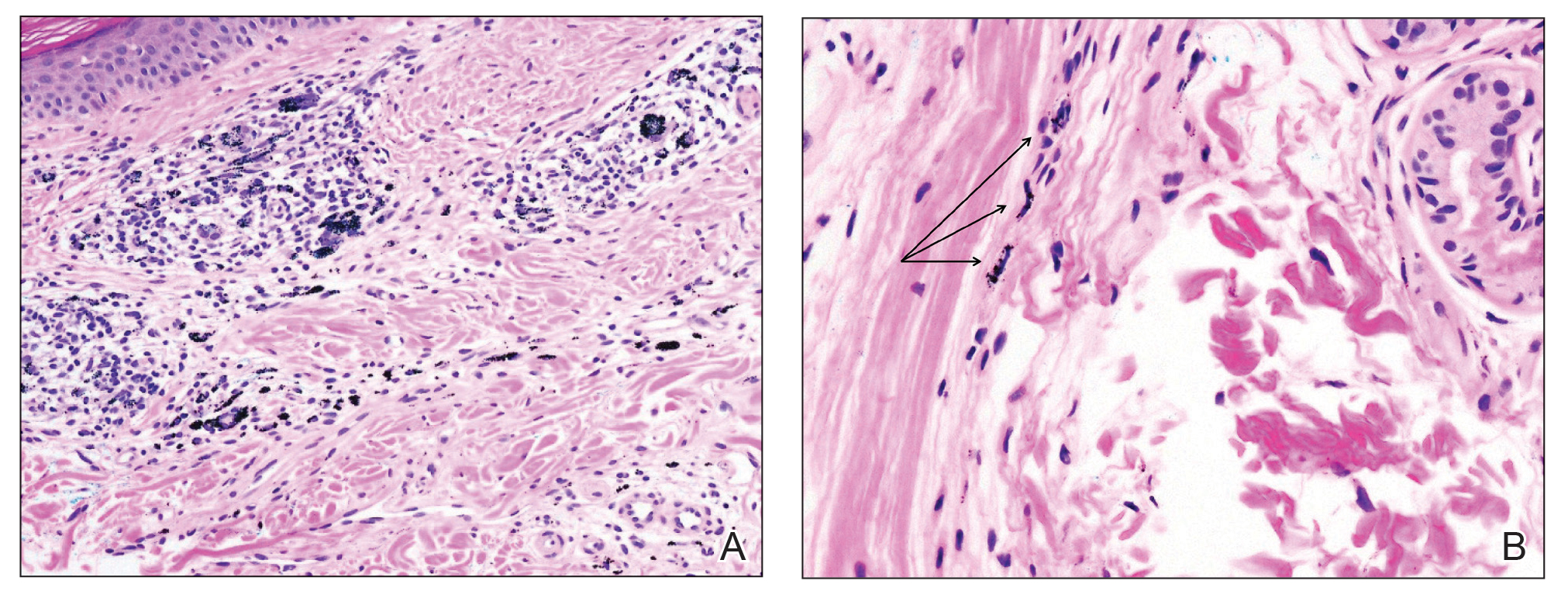

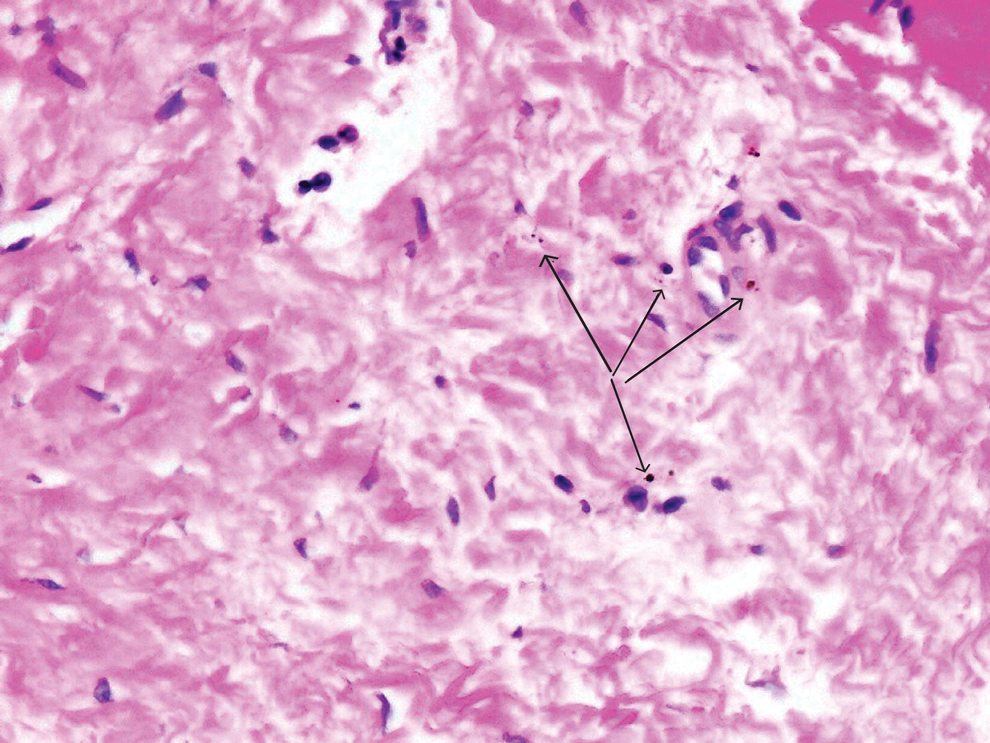

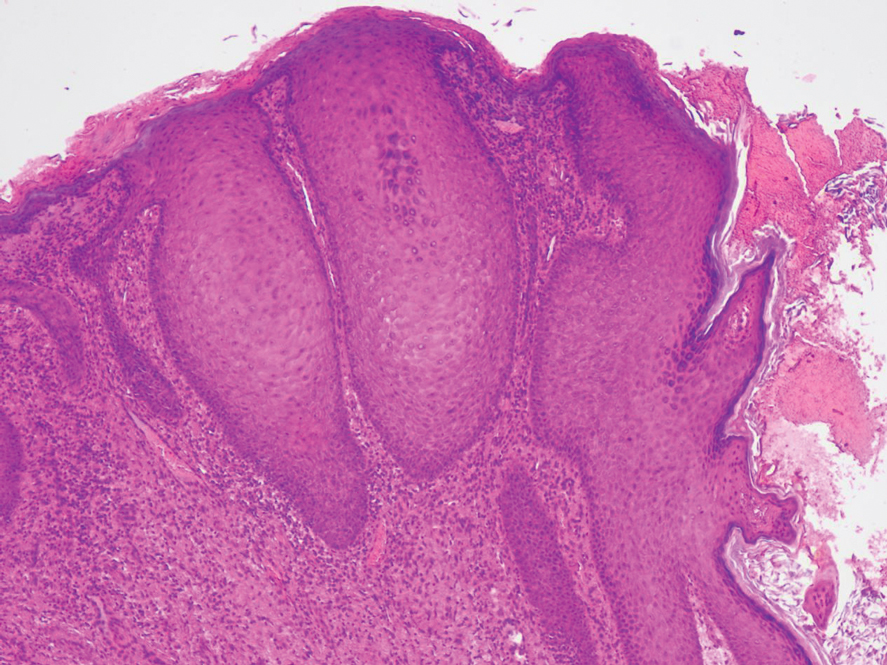

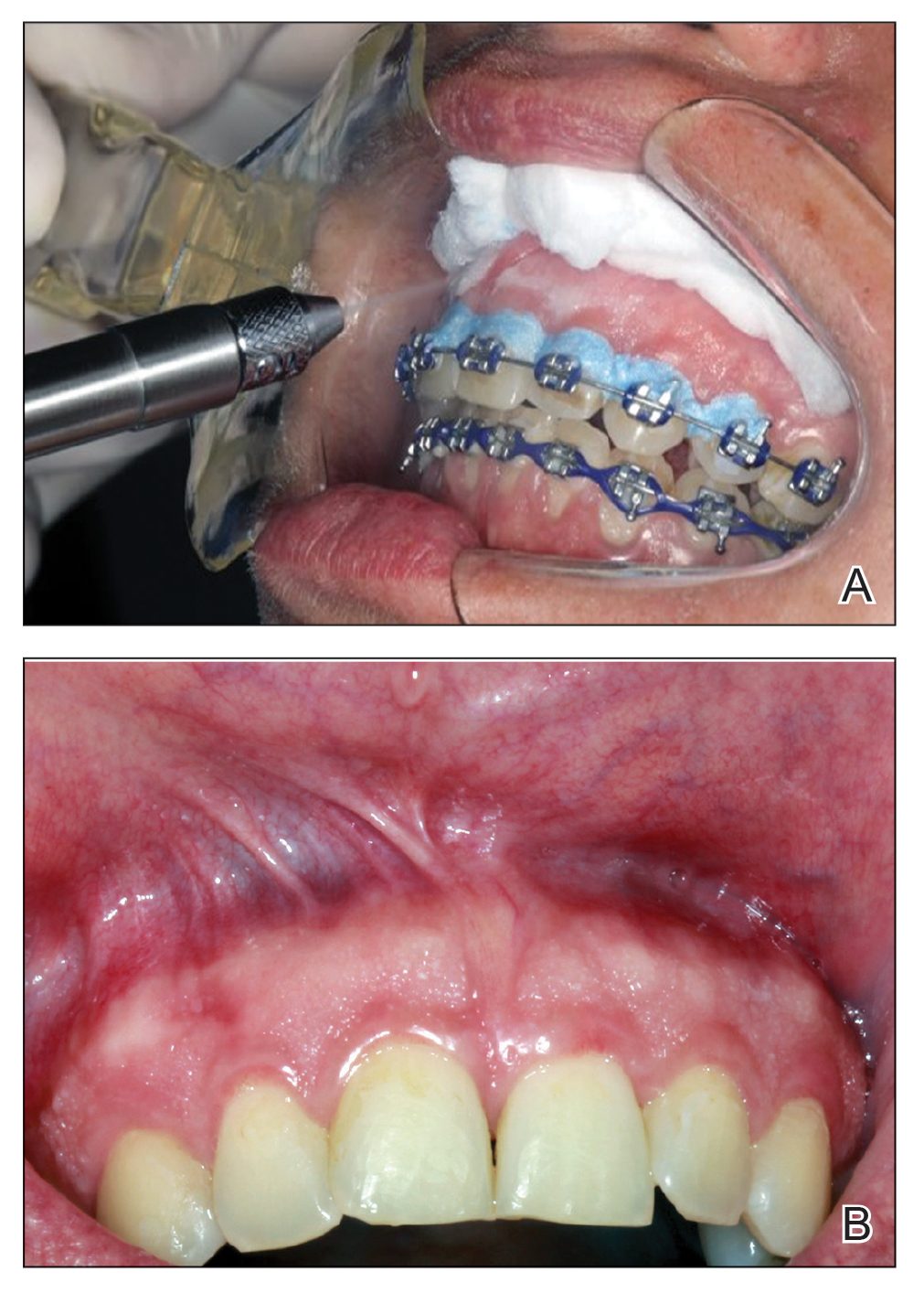

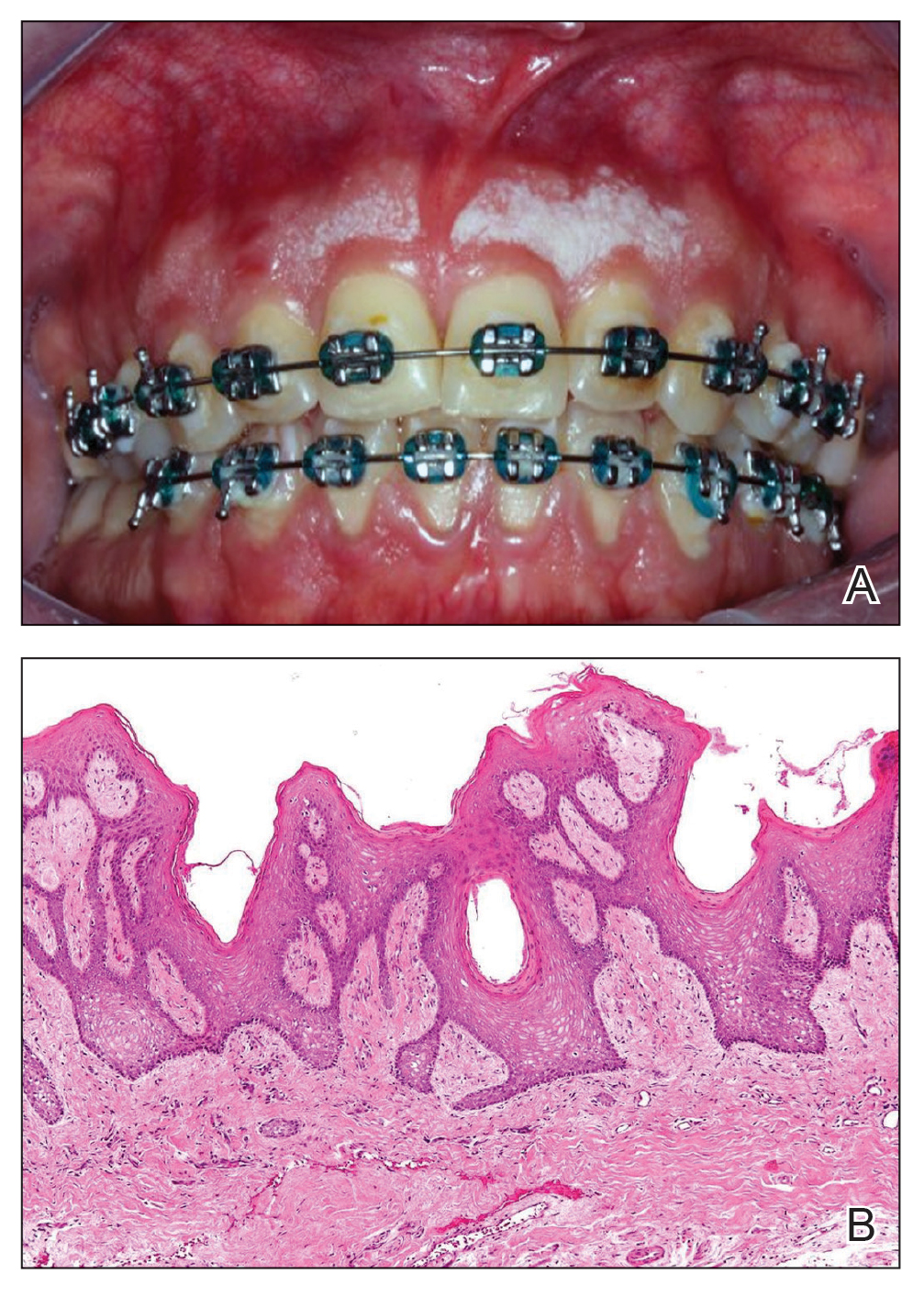

A 52-year-old woman with a history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) presented with alopecia and a tender lesion on the scalp of 5 years’ duration (Figure 1). The patient had no history of a similar lesion, and no other lesions were present. A biopsy performed at an outside clinic a few weeks to months prior to the initial presentation to our clinic showed NXG (Figure 2). Evaluation at our clinic revealed a 4x4-cm orange-brown annular plaque on the left parietal scalp. Serum and urine protein electrophoresis studies were negative. The patient reported she was up to date with recommended screenings such as mammography and colonoscopy.

We started the patient on topical triamcinolone and topical ruxolitinib and administered intralesional triamcinolone. She was already taking hydroxychloroquine and leflunomide for SLE. Three weeks later, she returned with improved symptoms and appearance (Figure 1). She remained on intralesional triamcinolone and ruxolitinib and continues to experience improvement.

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is rare and typically is associated with monoclonal gammopathy.2 In one study, 83 of 100 of patients with NXG presented with or were found to have a monoclonal gammopathy.2 In another study, paraproteinemia was detected in 82.1% of patients.3 The majority of case reports and systematic reviews detail periorbital or thoracic lesions.4 The location on the scalp and lack of association with paraproteinemia make this a rare presentation of NXG. Studies may be warranted to explore any association of SLE with NXG if more cases present.

In a multicenter cross-sectional study and systematic review of 235 patients with NXG, 87% were White, 12% were Asian, and only 1% were Black or African American.3 The limited representation of skin of color raises concern for the possibility of missed diagnoses and delays in care.

Treatment of NXG often is multimodal with use of intravenous immunoglobulin, oral steroids, chlorambucil, melphalan, and other alkylating agents, and response is variable.3-6 Recent studies show treatment effectiveness with Janus kinase inhibitors in granulomatous dermatitides.7-9 As our patient was not responding to prior treatments, we decided to try ruxolitinib, and she has continued to improve with it.10,11 Interestingly, the patient experienced continued improvement with intralesional triamcinolone, which is not often reported in the literature.2-6 Overall, NXG is an extremely rare condition that requires special care in workup to rule out paraproteinemia and a thoughtful approach to treatment modalities.

- Emile JF, Abla O, Fraitag S, et al. Revised classification of histiocytoses and neoplasms of the macrophage-dendritic cell lineages. Blood. 2016;127:2672-2681.

- Spicknall KE, Mehregan DA. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1-10.

- Nelson CA, Zhong CS, Hashemi DA, et al. A multicenter cross-sectional study and systematic review of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma with proposed diagnostic criteria. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:270-279.

- Huynh KN, Nguyen BD. Histiocytosis and neoplasms of macrophagedendritic cell lineages: multimodality imaging with emphasis on PET/CT. Radiographics. 2021;41:576-594. doi: 10.1148/rg.2021200096

- Hilal T, DiCaudo DJ, Connolly SM, et al. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma: a 30-year single-center experience. Ann Hematol. 2018;97:1471-1479.

- Oumeish OY, Oumeish I, Tarawneh M, et al. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma associated with paraproteinemia and non- Hodgkin’s lymphoma developing into chronic lymphocytic leukemia: the first case reported in the literature and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:306-310.

- Damsky W, Thakral D, McGeary MK, et al. Janus kinase inhibition induces disease remission in cutaneous sarcoidosis and granuloma annulare. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:612-621. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2019.05.098

- Wang A, Rahman NT, McGeary MK, et al. Treatment of granuloma annulare and suppression of proinflammatory cytokine activity with tofacitinib. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147:1795-1809. doi:10.1016 /j.jaci.2020.10.012

- Stratman S, Amara S, Tan KJ, et al. Systemic Janus kinase inhibitors in the management of granuloma annulare. Arch Dermatol Res. 2025;317:743. doi:10.1007/s00403-025-04248-1

- McPhie ML, Swales WC, Gooderham MJ. Improvement of granulomatous skin conditions with tofacitinib in three patients: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2021;9:2050313X211039477. doi: 10.1177/2050313X211039477

- Sood S, Heung M, Georgakopoulos JR, et al. Use of Janus kinase inhibitors for granulomatous dermatoses: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:357-359. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.03.024

To the Editor:

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma (NXG) is classified as a cutaneous non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis, often seen with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance or multiple myeloma.1 Clinically, it appears as a red or yellow plaque with occasional ulceration and telangiectasias, most commonly seen periorbitally and on the trunk. On pathology, NXG appears as necrobiosis, giant cells, and various inflammatory cells extending into the subcutaneous tissue.2 In this article, we describe a rare presentation of NXG in location and skin type.

A 52-year-old woman with a history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) presented with alopecia and a tender lesion on the scalp of 5 years’ duration (Figure 1). The patient had no history of a similar lesion, and no other lesions were present. A biopsy performed at an outside clinic a few weeks to months prior to the initial presentation to our clinic showed NXG (Figure 2). Evaluation at our clinic revealed a 4x4-cm orange-brown annular plaque on the left parietal scalp. Serum and urine protein electrophoresis studies were negative. The patient reported she was up to date with recommended screenings such as mammography and colonoscopy.

We started the patient on topical triamcinolone and topical ruxolitinib and administered intralesional triamcinolone. She was already taking hydroxychloroquine and leflunomide for SLE. Three weeks later, she returned with improved symptoms and appearance (Figure 1). She remained on intralesional triamcinolone and ruxolitinib and continues to experience improvement.

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is rare and typically is associated with monoclonal gammopathy.2 In one study, 83 of 100 of patients with NXG presented with or were found to have a monoclonal gammopathy.2 In another study, paraproteinemia was detected in 82.1% of patients.3 The majority of case reports and systematic reviews detail periorbital or thoracic lesions.4 The location on the scalp and lack of association with paraproteinemia make this a rare presentation of NXG. Studies may be warranted to explore any association of SLE with NXG if more cases present.

In a multicenter cross-sectional study and systematic review of 235 patients with NXG, 87% were White, 12% were Asian, and only 1% were Black or African American.3 The limited representation of skin of color raises concern for the possibility of missed diagnoses and delays in care.

Treatment of NXG often is multimodal with use of intravenous immunoglobulin, oral steroids, chlorambucil, melphalan, and other alkylating agents, and response is variable.3-6 Recent studies show treatment effectiveness with Janus kinase inhibitors in granulomatous dermatitides.7-9 As our patient was not responding to prior treatments, we decided to try ruxolitinib, and she has continued to improve with it.10,11 Interestingly, the patient experienced continued improvement with intralesional triamcinolone, which is not often reported in the literature.2-6 Overall, NXG is an extremely rare condition that requires special care in workup to rule out paraproteinemia and a thoughtful approach to treatment modalities.

To the Editor:

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma (NXG) is classified as a cutaneous non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis, often seen with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance or multiple myeloma.1 Clinically, it appears as a red or yellow plaque with occasional ulceration and telangiectasias, most commonly seen periorbitally and on the trunk. On pathology, NXG appears as necrobiosis, giant cells, and various inflammatory cells extending into the subcutaneous tissue.2 In this article, we describe a rare presentation of NXG in location and skin type.

A 52-year-old woman with a history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) presented with alopecia and a tender lesion on the scalp of 5 years’ duration (Figure 1). The patient had no history of a similar lesion, and no other lesions were present. A biopsy performed at an outside clinic a few weeks to months prior to the initial presentation to our clinic showed NXG (Figure 2). Evaluation at our clinic revealed a 4x4-cm orange-brown annular plaque on the left parietal scalp. Serum and urine protein electrophoresis studies were negative. The patient reported she was up to date with recommended screenings such as mammography and colonoscopy.

We started the patient on topical triamcinolone and topical ruxolitinib and administered intralesional triamcinolone. She was already taking hydroxychloroquine and leflunomide for SLE. Three weeks later, she returned with improved symptoms and appearance (Figure 1). She remained on intralesional triamcinolone and ruxolitinib and continues to experience improvement.

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is rare and typically is associated with monoclonal gammopathy.2 In one study, 83 of 100 of patients with NXG presented with or were found to have a monoclonal gammopathy.2 In another study, paraproteinemia was detected in 82.1% of patients.3 The majority of case reports and systematic reviews detail periorbital or thoracic lesions.4 The location on the scalp and lack of association with paraproteinemia make this a rare presentation of NXG. Studies may be warranted to explore any association of SLE with NXG if more cases present.

In a multicenter cross-sectional study and systematic review of 235 patients with NXG, 87% were White, 12% were Asian, and only 1% were Black or African American.3 The limited representation of skin of color raises concern for the possibility of missed diagnoses and delays in care.

Treatment of NXG often is multimodal with use of intravenous immunoglobulin, oral steroids, chlorambucil, melphalan, and other alkylating agents, and response is variable.3-6 Recent studies show treatment effectiveness with Janus kinase inhibitors in granulomatous dermatitides.7-9 As our patient was not responding to prior treatments, we decided to try ruxolitinib, and she has continued to improve with it.10,11 Interestingly, the patient experienced continued improvement with intralesional triamcinolone, which is not often reported in the literature.2-6 Overall, NXG is an extremely rare condition that requires special care in workup to rule out paraproteinemia and a thoughtful approach to treatment modalities.

- Emile JF, Abla O, Fraitag S, et al. Revised classification of histiocytoses and neoplasms of the macrophage-dendritic cell lineages. Blood. 2016;127:2672-2681.

- Spicknall KE, Mehregan DA. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1-10.

- Nelson CA, Zhong CS, Hashemi DA, et al. A multicenter cross-sectional study and systematic review of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma with proposed diagnostic criteria. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:270-279.

- Huynh KN, Nguyen BD. Histiocytosis and neoplasms of macrophagedendritic cell lineages: multimodality imaging with emphasis on PET/CT. Radiographics. 2021;41:576-594. doi: 10.1148/rg.2021200096

- Hilal T, DiCaudo DJ, Connolly SM, et al. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma: a 30-year single-center experience. Ann Hematol. 2018;97:1471-1479.

- Oumeish OY, Oumeish I, Tarawneh M, et al. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma associated with paraproteinemia and non- Hodgkin’s lymphoma developing into chronic lymphocytic leukemia: the first case reported in the literature and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:306-310.

- Damsky W, Thakral D, McGeary MK, et al. Janus kinase inhibition induces disease remission in cutaneous sarcoidosis and granuloma annulare. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:612-621. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2019.05.098

- Wang A, Rahman NT, McGeary MK, et al. Treatment of granuloma annulare and suppression of proinflammatory cytokine activity with tofacitinib. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147:1795-1809. doi:10.1016 /j.jaci.2020.10.012

- Stratman S, Amara S, Tan KJ, et al. Systemic Janus kinase inhibitors in the management of granuloma annulare. Arch Dermatol Res. 2025;317:743. doi:10.1007/s00403-025-04248-1

- McPhie ML, Swales WC, Gooderham MJ. Improvement of granulomatous skin conditions with tofacitinib in three patients: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2021;9:2050313X211039477. doi: 10.1177/2050313X211039477

- Sood S, Heung M, Georgakopoulos JR, et al. Use of Janus kinase inhibitors for granulomatous dermatoses: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:357-359. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.03.024

- Emile JF, Abla O, Fraitag S, et al. Revised classification of histiocytoses and neoplasms of the macrophage-dendritic cell lineages. Blood. 2016;127:2672-2681.

- Spicknall KE, Mehregan DA. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1-10.

- Nelson CA, Zhong CS, Hashemi DA, et al. A multicenter cross-sectional study and systematic review of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma with proposed diagnostic criteria. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:270-279.

- Huynh KN, Nguyen BD. Histiocytosis and neoplasms of macrophagedendritic cell lineages: multimodality imaging with emphasis on PET/CT. Radiographics. 2021;41:576-594. doi: 10.1148/rg.2021200096

- Hilal T, DiCaudo DJ, Connolly SM, et al. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma: a 30-year single-center experience. Ann Hematol. 2018;97:1471-1479.

- Oumeish OY, Oumeish I, Tarawneh M, et al. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma associated with paraproteinemia and non- Hodgkin’s lymphoma developing into chronic lymphocytic leukemia: the first case reported in the literature and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:306-310.

- Damsky W, Thakral D, McGeary MK, et al. Janus kinase inhibition induces disease remission in cutaneous sarcoidosis and granuloma annulare. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:612-621. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2019.05.098

- Wang A, Rahman NT, McGeary MK, et al. Treatment of granuloma annulare and suppression of proinflammatory cytokine activity with tofacitinib. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147:1795-1809. doi:10.1016 /j.jaci.2020.10.012

- Stratman S, Amara S, Tan KJ, et al. Systemic Janus kinase inhibitors in the management of granuloma annulare. Arch Dermatol Res. 2025;317:743. doi:10.1007/s00403-025-04248-1

- McPhie ML, Swales WC, Gooderham MJ. Improvement of granulomatous skin conditions with tofacitinib in three patients: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2021;9:2050313X211039477. doi: 10.1177/2050313X211039477

- Sood S, Heung M, Georgakopoulos JR, et al. Use of Janus kinase inhibitors for granulomatous dermatoses: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:357-359. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.03.024

Rare Case of Necrobiotic Xanthogranuloma on the Scalp

Rare Case of Necrobiotic Xanthogranuloma on the Scalp

PRACTICE POINTS

- In skin of color, necrobiotic xanthogranuloma can appear orange or brown compared to its yellow appearance in lighter skin types.

- When necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is suspected, a thorough malignancy workup should be conducted.

Upadacitinib for Treatment of Severe Atopic Dermatitis in a Child

Upadacitinib for Treatment of Severe Atopic Dermatitis in a Child

To the Editor:

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is one of the most common chronic inflammatory skin diseases and is characterized by age-related morphology and distribution of lesions. Although AD can manifest at any age, it often develops during childhood, with an estimated worldwide prevalence of 15% to 25% in children and 1% to 10% in adults.1 Clinical manifestation includes chronic or recurrent xerosis, pruritic eczematous lesions involving the flexural and extensor areas, and cutaneous infections. Immediate skin test reactivity and elevated total IgE levels can be found in up to 80% of patients.2

Although the pathogenesis of AD is complex, multifactorial, and not completely understood, some studies have highlighted the central role of a type 2 immune response, resulting in skin barrier dysfunction, cutaneous inflammation, and neuroimmune dysregulation.3,4 The primary goals of treatment are to mitigate these factors through improvement of symptoms and long-term disease control. Topical emollients are used to repair the epidermal barrier, and topical anti-inflammatory therapy with corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors might be applied during flares; however, systemic treatment is essential for patients with moderate to severe AD that is not controlled with topical treatment or phototherapy.5

Until recently, systemic immunosuppressant agents such as corticosteroids, cyclosporine, and methotrexate were the only systemic treatment options for severe AD; however, their effectiveness is limited and they may cause serious long-term adverse events, limiting their regular usage, especially in children.6

Therapies that target type 2 immune responses include anti–IL-4/IL-13, anti–IL-13, and anti–IL-31 biologics. Dupilumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody targeting the type 2 immune response. This biologic directly binds to IL-4Rα,which prevents signaling by both the IL-4 and IL-13 pathways. Dupilumab was the first biologic approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of moderate to severe AD, with demonstrated efficacy and a favorable safety profile.5

In addition to biologics, Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors belong to the small-molecule class. These drugs block the JAK/STAT intracellular signaling pathway, leading to inhibition of downstream effects triggered by several cytokines related to AD pathogenesis. Upadacitinib is an oral JAK inhibitor that was approved by the FDA in 2022 for treatment of severe AD in adults and children aged 12 years and older. This drug promotes a selective and reversible JAK-1 inhibition and has demonstrated rapid onset of action and a sustained reduction in the signs and symptoms of AD.7 We report the case of a child with recalcitrant severe AD that showed significant clinical improvement following off-label treatment with upadacitinib after showing a poor clinical response to dupilumab.

A 9-year-old girl presented to our pediatrics department with progressive worsening of severe AD over the previous 2 years. The patient had been diagnosed with AD at 6 months old, at which time she was treated with several prescribed moisturizers, topical and systemic corticosteroids, and calcineurin inhibitors with no clinical improvement.

The patient initially presented to us for evaluation of severe pruritus and associated sleep loss at age 7 years; physical examination revealed severe xerosis and disseminated pruritic eczematous lesions. Her SCORAD (SCORing Atopic Dermatitis) score was 70 (range, 0-103), and laboratory testing showed a high eosinophil count (1.5×103/μL [range, 0-0.6×103], 13%) and IgE level (1686 κU/L [range, 0-90]); a skin prick test on the forearm was positive for Blomia tropicalis.

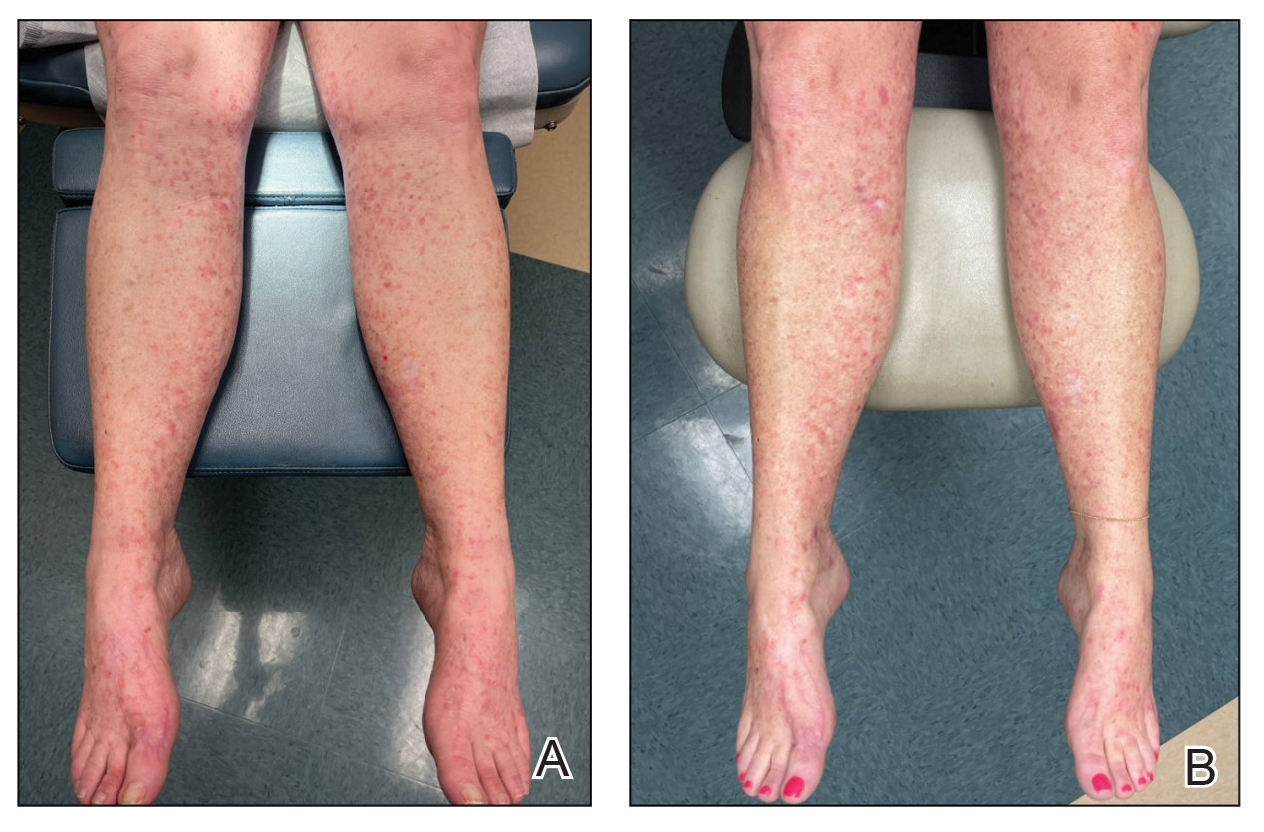

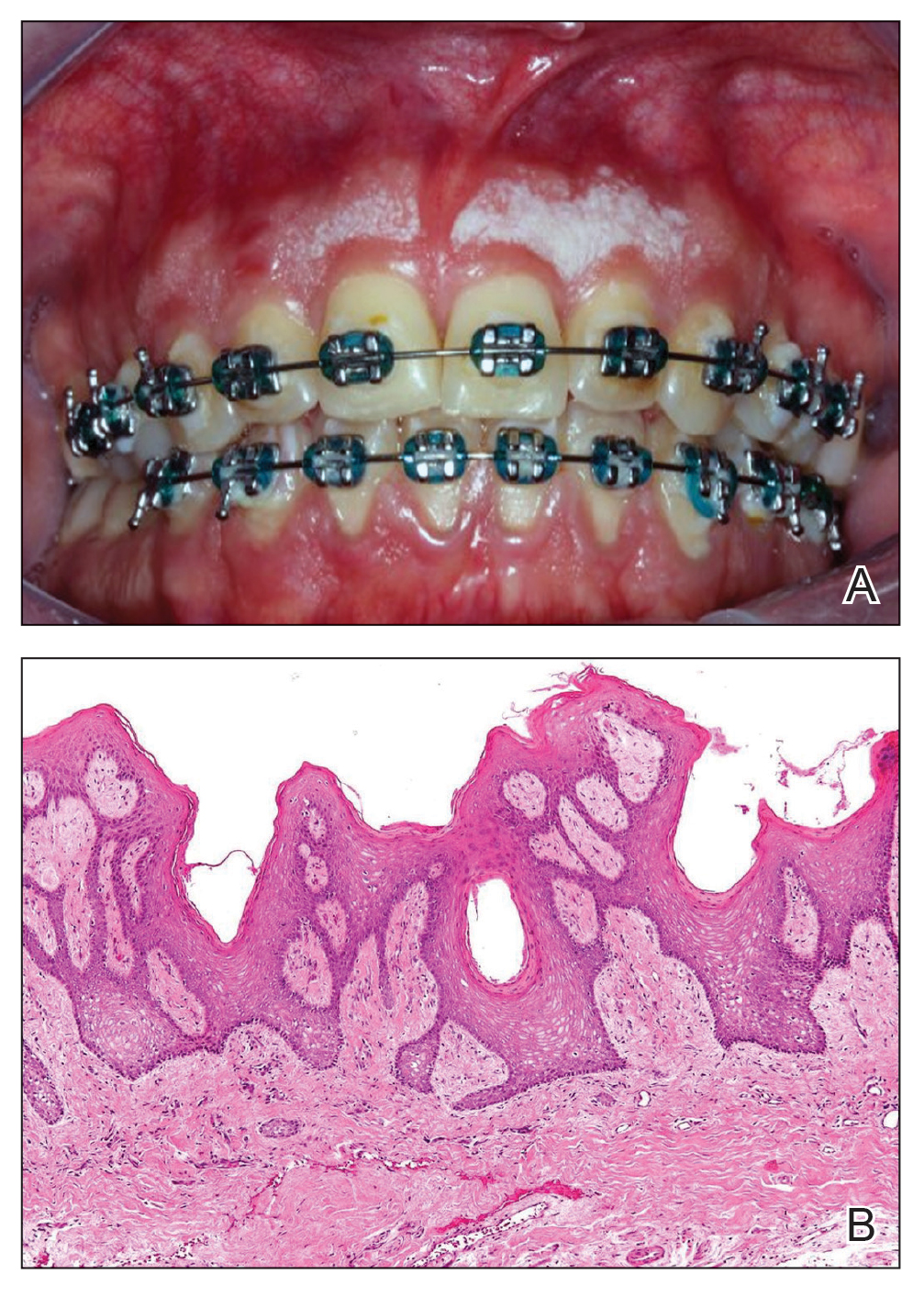

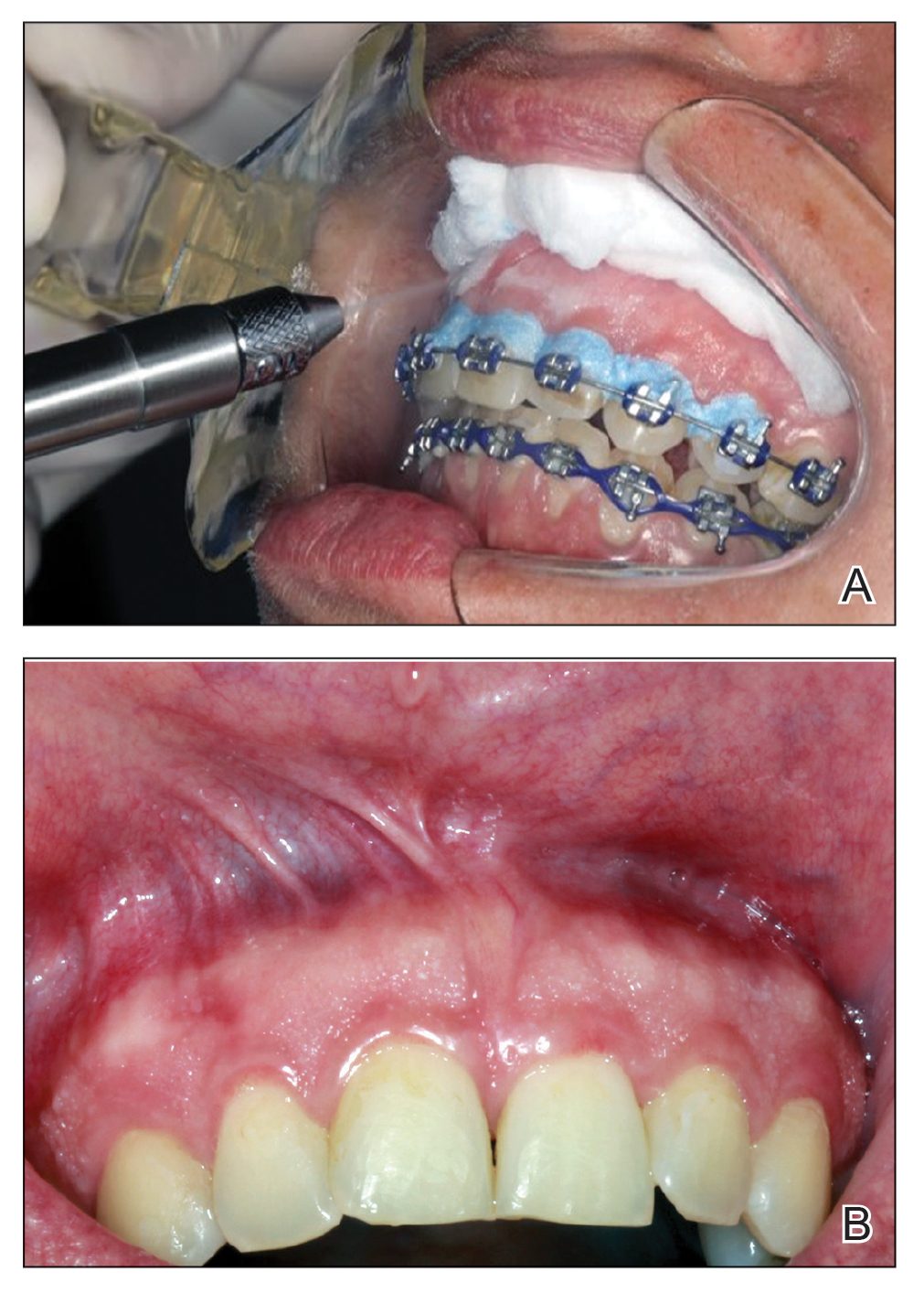

Following her presentation with severe AD at 7 years old, the patient was prescribed systemic treatments including methotrexate and cyclosporine. During treatment with these agents, she presented to our department with several bacterial skin infections that required oral and intravenous antibiotics for treatment. These agents ultimately were discontinued after 12 months due to the adverse effects and poor clinical improvement. At age 8 years, the patient received an initial 600-mg dose of dupilumab followed by 300 mg subcutaneously every 4 weeks for 6 months along with topical corticosteroids and emollients. During treatment with dupilumab, the patient showed no clinical improvement (SCORAD score, 62). Therefore, we decided to change the dose to 200 mg every 2 weeks. The patient still showed no improvement and presented at age 9 years with moderate conjunctivitis and oculocutaneous infection caused by herpes simplex virus, which required treatment with oral acyclovir (Figure 1).

Considering the severe and refractory clinical course and the poor response to the recommended treatments for the patient’s age, oral upadacitinib was administered off label at a dose of 15 mg once daily after informed consent was obtained from her parents. She returned for follow-up once weekly for 1 month. Three days after starting treatment with upadacitinib, she showed considerable improvement in itch, and her SCORAD score decreased from 62 to 31 after 15 days. After 2 months of treatment, she reported no pruritus or sleep loss, and her SCORAD score was 4.5 (Figure 2). The results of a complete blood count, coagulation function test, and liver and kidney function tests were normal at 6-month and 12-month follow-up during upadacitinib therapy. No adverse effects were observed. The patient currently has completed 18 months of treatment, and the disease remains in complete remission.

Atopic dermatitis is highly prevalent in children. According to the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood, the prevalence of eczema in 2009 was 8.2% among children aged 6 to 7 years and 5% among adolescents aged between 13 and 14 years in Brazil; severe AD was present in 1.5% of children in both age groups.8

The main systemic therapies currently available for patients with severe AD are immunosuppressants, biologics, and small-molecule drugs. The considerable adverse effects of immunosuppressants limit their application. Dupilumab is considered the first-line treatment for children with severe AD. Clinical trials and case reports have demonstrated that dupilumab is effective in patients with AD, promoting notable improvement of pruritic eczematous lesions and quality-of-life scores.9 Dupilumab has been approved by the FDA for children older than 6 months, and some studies have shown up to a 49% reduction of pruritus in this age group.9 The main reported adverse effects were mild conjunctivitis and oral herpes simplex virus infection.9,10

Upadacitinib is a reversible and selective JAK-1 inhibitor approved by the FDA for treatment of severe AD in patients aged 12 years and older. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evaluated adolescents (12-17 years) and adults (18-75 years) with moderate to severe AD who were randomly assigned (1:1:1) to receive upadacitinib 15 mg, upadacitinib 30 mg, or placebo once daily for 16 weeks.11 A higher proportion of patients achieved an Eczema Area and Severity Index score of 75 at week 16 with both upadacitinib 15 mg daily (70%) and 30 mg daily (80%) compared to placebo. Improvements also were observed in both SCORAD and pruritus scores. The most commonly reported adverse events were acne, lipid profile abnormalities, and herpes zoster infection.11

Our patient was a child with severe refractory AD that demonstrated a poor treatment response to dupilumab. When switched to off-label upadacitinib, her disease was effectively controlled; the treatment also was well tolerated with no adverse effects. Reports of upadacitinib used to treat AD in patients younger than 12 years are limited in the literature. One case report described a 9-year-old child with concurrent alopecia areata and severe AD who was successfully treated off label with upadacitinib.12 A clinical trial also has evaluated the pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of upadacitinib in children aged 2 to 12 years with severe AD (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03646604); although the trial was completed in 2024, at the time of this review (July 2025), the results have not been published.

Interestingly, there have been a few reports of adults with severe AD that failed to respond to treatment with immunosuppressants and dupilumab but showed notable clinical improvement when therapy was switched to upadacitinib,13,14 as we noticed with our patient. These findings suggest that the JAK-STAT intracellular signaling pathway plays an important role in the pathogenesis of AD.

Continued development of safe and efficient targeted treatment for children with severe AD is critical. Upadacitinib was a safe and effective option for treatment of refractory and severe AD in our patient; however, further studies are needed to confirm both the efficacy and safety of JAK inhibitors in this age group.

- Weidinger S, Novak N. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 2016;387:1109-1122.

- Wollenberg A, Christen-Zäch S, Taieb A, et al. ETFAD/EADV Eczema Task Force 2020 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adults and children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34 :2717-2744.

- Hanifin JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venererol. 1980;92:44-47.

- Nakahara T, Kido-Nakahara M, Tsuji G, et al. Basics and recent advances in the pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol. 2021;48:130-139.

- Wollenberg A, Kinberger M, Arents B, et al. European guideline (EuroGuiDerm) on atopic eczema: part I—systemic therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:1409-1431.

- Chu DK, Schneider L, Asiniwasis RN, et al. Atopic dermatitis (eczema) guidelines: 2023 American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology/American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters GRADE– and Institute of Medicine–based recommendations. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2024;132:274-312.

- Rick JW, Lio P, Atluri S, et al. Atopic dermatitis: a guide to transitioning to janus kinase inhibitors. Dermatitis. 2023;34:297-300.

- Prado E, Pastorino AC, Harari DK, et al. Severe atopic dermatitis: a practical treatment guide from the Brazilian Association of Allergy and Immunology and the Brazilian Society of Pediatrics. Arq Asma Alerg Imunol. 2022;6:432-467.

- Paller AS, Simpson EL, Siegfried EC, et al. Dupilumab in children aged 6 months to younger than 6 years with uncontrolled atopic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2022;400:908-919.

- Blauvelt A, de Bruin-Weller M, Gooderham M, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1-year, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2287-2303.

- Guttman-Yassky E, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, et al. Once-daily upadacitinib versus placebo in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2): results from two replicate double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2021 ;397:2151-2168.

- Yu D, Ren Y. Upadacitinib for successful treatment of alopecia universalis in a child: a case report and literature review. Acta Derm Venererol. 2023;103:adv5578.

- Cantelli M, Martora F, Patruno C, et al. Upadacitinib improved alopecia areata in a patient with atopic dermatitis: a case report. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:E15346.

- Gambardella A, Licata G, Calabrese G, et al. Dual efficacy of upadacitinib in 2 patients with concomitant severe atopic dermatitis and alopecia areata. Dermatitis. 2021;32:E85-E86.

To the Editor:

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is one of the most common chronic inflammatory skin diseases and is characterized by age-related morphology and distribution of lesions. Although AD can manifest at any age, it often develops during childhood, with an estimated worldwide prevalence of 15% to 25% in children and 1% to 10% in adults.1 Clinical manifestation includes chronic or recurrent xerosis, pruritic eczematous lesions involving the flexural and extensor areas, and cutaneous infections. Immediate skin test reactivity and elevated total IgE levels can be found in up to 80% of patients.2

Although the pathogenesis of AD is complex, multifactorial, and not completely understood, some studies have highlighted the central role of a type 2 immune response, resulting in skin barrier dysfunction, cutaneous inflammation, and neuroimmune dysregulation.3,4 The primary goals of treatment are to mitigate these factors through improvement of symptoms and long-term disease control. Topical emollients are used to repair the epidermal barrier, and topical anti-inflammatory therapy with corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors might be applied during flares; however, systemic treatment is essential for patients with moderate to severe AD that is not controlled with topical treatment or phototherapy.5

Until recently, systemic immunosuppressant agents such as corticosteroids, cyclosporine, and methotrexate were the only systemic treatment options for severe AD; however, their effectiveness is limited and they may cause serious long-term adverse events, limiting their regular usage, especially in children.6

Therapies that target type 2 immune responses include anti–IL-4/IL-13, anti–IL-13, and anti–IL-31 biologics. Dupilumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody targeting the type 2 immune response. This biologic directly binds to IL-4Rα,which prevents signaling by both the IL-4 and IL-13 pathways. Dupilumab was the first biologic approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of moderate to severe AD, with demonstrated efficacy and a favorable safety profile.5

In addition to biologics, Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors belong to the small-molecule class. These drugs block the JAK/STAT intracellular signaling pathway, leading to inhibition of downstream effects triggered by several cytokines related to AD pathogenesis. Upadacitinib is an oral JAK inhibitor that was approved by the FDA in 2022 for treatment of severe AD in adults and children aged 12 years and older. This drug promotes a selective and reversible JAK-1 inhibition and has demonstrated rapid onset of action and a sustained reduction in the signs and symptoms of AD.7 We report the case of a child with recalcitrant severe AD that showed significant clinical improvement following off-label treatment with upadacitinib after showing a poor clinical response to dupilumab.

A 9-year-old girl presented to our pediatrics department with progressive worsening of severe AD over the previous 2 years. The patient had been diagnosed with AD at 6 months old, at which time she was treated with several prescribed moisturizers, topical and systemic corticosteroids, and calcineurin inhibitors with no clinical improvement.

The patient initially presented to us for evaluation of severe pruritus and associated sleep loss at age 7 years; physical examination revealed severe xerosis and disseminated pruritic eczematous lesions. Her SCORAD (SCORing Atopic Dermatitis) score was 70 (range, 0-103), and laboratory testing showed a high eosinophil count (1.5×103/μL [range, 0-0.6×103], 13%) and IgE level (1686 κU/L [range, 0-90]); a skin prick test on the forearm was positive for Blomia tropicalis.

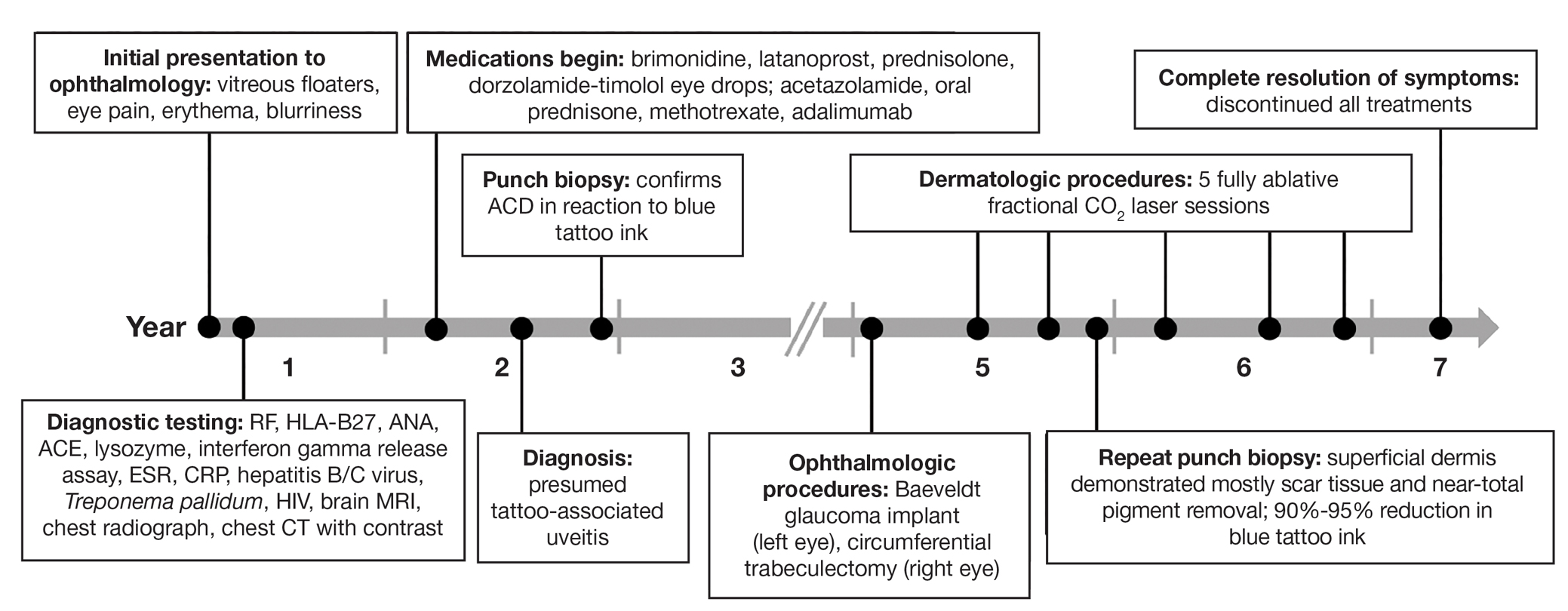

Following her presentation with severe AD at 7 years old, the patient was prescribed systemic treatments including methotrexate and cyclosporine. During treatment with these agents, she presented to our department with several bacterial skin infections that required oral and intravenous antibiotics for treatment. These agents ultimately were discontinued after 12 months due to the adverse effects and poor clinical improvement. At age 8 years, the patient received an initial 600-mg dose of dupilumab followed by 300 mg subcutaneously every 4 weeks for 6 months along with topical corticosteroids and emollients. During treatment with dupilumab, the patient showed no clinical improvement (SCORAD score, 62). Therefore, we decided to change the dose to 200 mg every 2 weeks. The patient still showed no improvement and presented at age 9 years with moderate conjunctivitis and oculocutaneous infection caused by herpes simplex virus, which required treatment with oral acyclovir (Figure 1).

Considering the severe and refractory clinical course and the poor response to the recommended treatments for the patient’s age, oral upadacitinib was administered off label at a dose of 15 mg once daily after informed consent was obtained from her parents. She returned for follow-up once weekly for 1 month. Three days after starting treatment with upadacitinib, she showed considerable improvement in itch, and her SCORAD score decreased from 62 to 31 after 15 days. After 2 months of treatment, she reported no pruritus or sleep loss, and her SCORAD score was 4.5 (Figure 2). The results of a complete blood count, coagulation function test, and liver and kidney function tests were normal at 6-month and 12-month follow-up during upadacitinib therapy. No adverse effects were observed. The patient currently has completed 18 months of treatment, and the disease remains in complete remission.

Atopic dermatitis is highly prevalent in children. According to the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood, the prevalence of eczema in 2009 was 8.2% among children aged 6 to 7 years and 5% among adolescents aged between 13 and 14 years in Brazil; severe AD was present in 1.5% of children in both age groups.8

The main systemic therapies currently available for patients with severe AD are immunosuppressants, biologics, and small-molecule drugs. The considerable adverse effects of immunosuppressants limit their application. Dupilumab is considered the first-line treatment for children with severe AD. Clinical trials and case reports have demonstrated that dupilumab is effective in patients with AD, promoting notable improvement of pruritic eczematous lesions and quality-of-life scores.9 Dupilumab has been approved by the FDA for children older than 6 months, and some studies have shown up to a 49% reduction of pruritus in this age group.9 The main reported adverse effects were mild conjunctivitis and oral herpes simplex virus infection.9,10

Upadacitinib is a reversible and selective JAK-1 inhibitor approved by the FDA for treatment of severe AD in patients aged 12 years and older. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evaluated adolescents (12-17 years) and adults (18-75 years) with moderate to severe AD who were randomly assigned (1:1:1) to receive upadacitinib 15 mg, upadacitinib 30 mg, or placebo once daily for 16 weeks.11 A higher proportion of patients achieved an Eczema Area and Severity Index score of 75 at week 16 with both upadacitinib 15 mg daily (70%) and 30 mg daily (80%) compared to placebo. Improvements also were observed in both SCORAD and pruritus scores. The most commonly reported adverse events were acne, lipid profile abnormalities, and herpes zoster infection.11

Our patient was a child with severe refractory AD that demonstrated a poor treatment response to dupilumab. When switched to off-label upadacitinib, her disease was effectively controlled; the treatment also was well tolerated with no adverse effects. Reports of upadacitinib used to treat AD in patients younger than 12 years are limited in the literature. One case report described a 9-year-old child with concurrent alopecia areata and severe AD who was successfully treated off label with upadacitinib.12 A clinical trial also has evaluated the pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of upadacitinib in children aged 2 to 12 years with severe AD (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03646604); although the trial was completed in 2024, at the time of this review (July 2025), the results have not been published.

Interestingly, there have been a few reports of adults with severe AD that failed to respond to treatment with immunosuppressants and dupilumab but showed notable clinical improvement when therapy was switched to upadacitinib,13,14 as we noticed with our patient. These findings suggest that the JAK-STAT intracellular signaling pathway plays an important role in the pathogenesis of AD.

Continued development of safe and efficient targeted treatment for children with severe AD is critical. Upadacitinib was a safe and effective option for treatment of refractory and severe AD in our patient; however, further studies are needed to confirm both the efficacy and safety of JAK inhibitors in this age group.

To the Editor:

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is one of the most common chronic inflammatory skin diseases and is characterized by age-related morphology and distribution of lesions. Although AD can manifest at any age, it often develops during childhood, with an estimated worldwide prevalence of 15% to 25% in children and 1% to 10% in adults.1 Clinical manifestation includes chronic or recurrent xerosis, pruritic eczematous lesions involving the flexural and extensor areas, and cutaneous infections. Immediate skin test reactivity and elevated total IgE levels can be found in up to 80% of patients.2

Although the pathogenesis of AD is complex, multifactorial, and not completely understood, some studies have highlighted the central role of a type 2 immune response, resulting in skin barrier dysfunction, cutaneous inflammation, and neuroimmune dysregulation.3,4 The primary goals of treatment are to mitigate these factors through improvement of symptoms and long-term disease control. Topical emollients are used to repair the epidermal barrier, and topical anti-inflammatory therapy with corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors might be applied during flares; however, systemic treatment is essential for patients with moderate to severe AD that is not controlled with topical treatment or phototherapy.5

Until recently, systemic immunosuppressant agents such as corticosteroids, cyclosporine, and methotrexate were the only systemic treatment options for severe AD; however, their effectiveness is limited and they may cause serious long-term adverse events, limiting their regular usage, especially in children.6

Therapies that target type 2 immune responses include anti–IL-4/IL-13, anti–IL-13, and anti–IL-31 biologics. Dupilumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody targeting the type 2 immune response. This biologic directly binds to IL-4Rα,which prevents signaling by both the IL-4 and IL-13 pathways. Dupilumab was the first biologic approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of moderate to severe AD, with demonstrated efficacy and a favorable safety profile.5

In addition to biologics, Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors belong to the small-molecule class. These drugs block the JAK/STAT intracellular signaling pathway, leading to inhibition of downstream effects triggered by several cytokines related to AD pathogenesis. Upadacitinib is an oral JAK inhibitor that was approved by the FDA in 2022 for treatment of severe AD in adults and children aged 12 years and older. This drug promotes a selective and reversible JAK-1 inhibition and has demonstrated rapid onset of action and a sustained reduction in the signs and symptoms of AD.7 We report the case of a child with recalcitrant severe AD that showed significant clinical improvement following off-label treatment with upadacitinib after showing a poor clinical response to dupilumab.

A 9-year-old girl presented to our pediatrics department with progressive worsening of severe AD over the previous 2 years. The patient had been diagnosed with AD at 6 months old, at which time she was treated with several prescribed moisturizers, topical and systemic corticosteroids, and calcineurin inhibitors with no clinical improvement.

The patient initially presented to us for evaluation of severe pruritus and associated sleep loss at age 7 years; physical examination revealed severe xerosis and disseminated pruritic eczematous lesions. Her SCORAD (SCORing Atopic Dermatitis) score was 70 (range, 0-103), and laboratory testing showed a high eosinophil count (1.5×103/μL [range, 0-0.6×103], 13%) and IgE level (1686 κU/L [range, 0-90]); a skin prick test on the forearm was positive for Blomia tropicalis.

Following her presentation with severe AD at 7 years old, the patient was prescribed systemic treatments including methotrexate and cyclosporine. During treatment with these agents, she presented to our department with several bacterial skin infections that required oral and intravenous antibiotics for treatment. These agents ultimately were discontinued after 12 months due to the adverse effects and poor clinical improvement. At age 8 years, the patient received an initial 600-mg dose of dupilumab followed by 300 mg subcutaneously every 4 weeks for 6 months along with topical corticosteroids and emollients. During treatment with dupilumab, the patient showed no clinical improvement (SCORAD score, 62). Therefore, we decided to change the dose to 200 mg every 2 weeks. The patient still showed no improvement and presented at age 9 years with moderate conjunctivitis and oculocutaneous infection caused by herpes simplex virus, which required treatment with oral acyclovir (Figure 1).

Considering the severe and refractory clinical course and the poor response to the recommended treatments for the patient’s age, oral upadacitinib was administered off label at a dose of 15 mg once daily after informed consent was obtained from her parents. She returned for follow-up once weekly for 1 month. Three days after starting treatment with upadacitinib, she showed considerable improvement in itch, and her SCORAD score decreased from 62 to 31 after 15 days. After 2 months of treatment, she reported no pruritus or sleep loss, and her SCORAD score was 4.5 (Figure 2). The results of a complete blood count, coagulation function test, and liver and kidney function tests were normal at 6-month and 12-month follow-up during upadacitinib therapy. No adverse effects were observed. The patient currently has completed 18 months of treatment, and the disease remains in complete remission.

Atopic dermatitis is highly prevalent in children. According to the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood, the prevalence of eczema in 2009 was 8.2% among children aged 6 to 7 years and 5% among adolescents aged between 13 and 14 years in Brazil; severe AD was present in 1.5% of children in both age groups.8

The main systemic therapies currently available for patients with severe AD are immunosuppressants, biologics, and small-molecule drugs. The considerable adverse effects of immunosuppressants limit their application. Dupilumab is considered the first-line treatment for children with severe AD. Clinical trials and case reports have demonstrated that dupilumab is effective in patients with AD, promoting notable improvement of pruritic eczematous lesions and quality-of-life scores.9 Dupilumab has been approved by the FDA for children older than 6 months, and some studies have shown up to a 49% reduction of pruritus in this age group.9 The main reported adverse effects were mild conjunctivitis and oral herpes simplex virus infection.9,10