User login

Solitary Plaque on the Nose

Solitary Plaque on the Nose

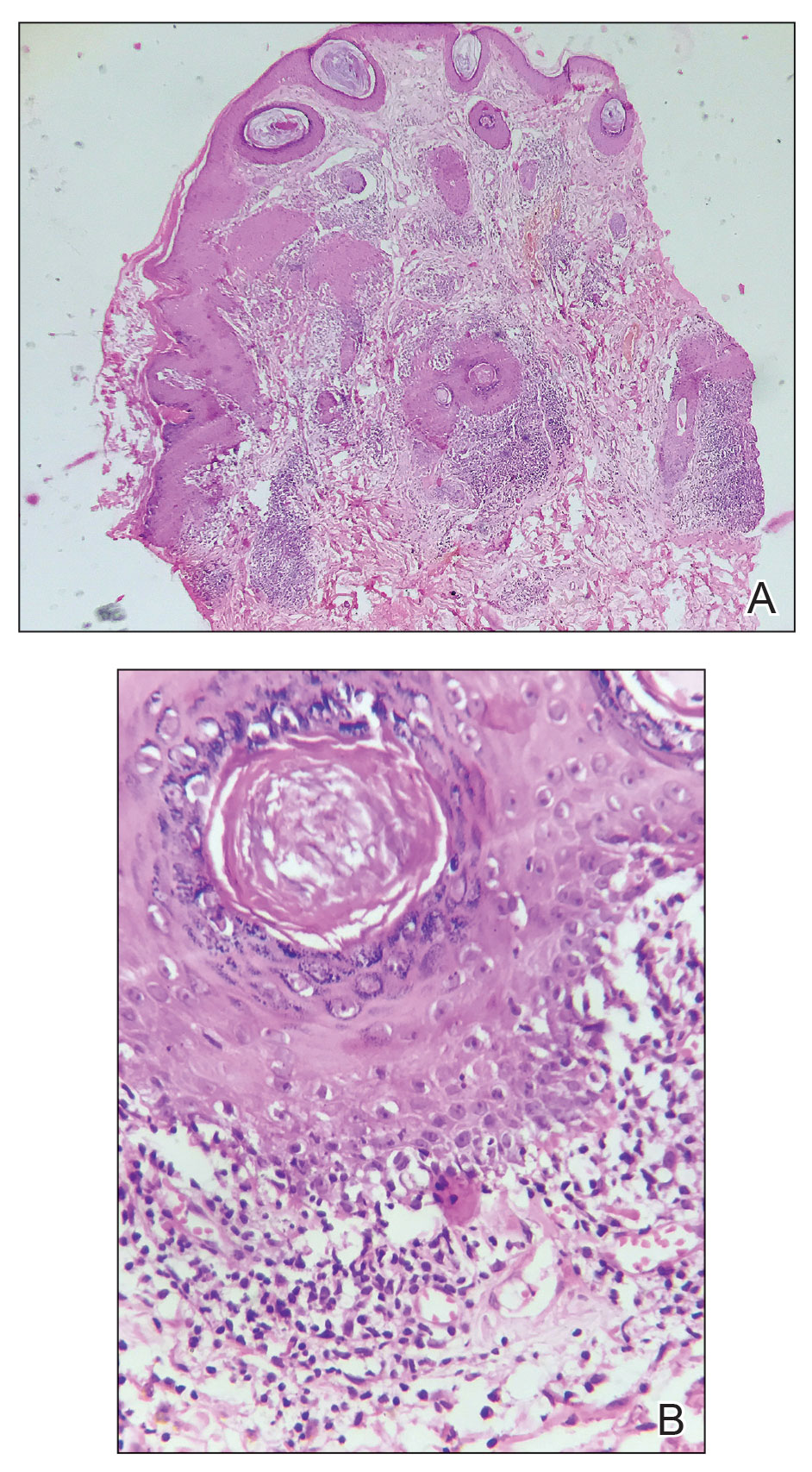

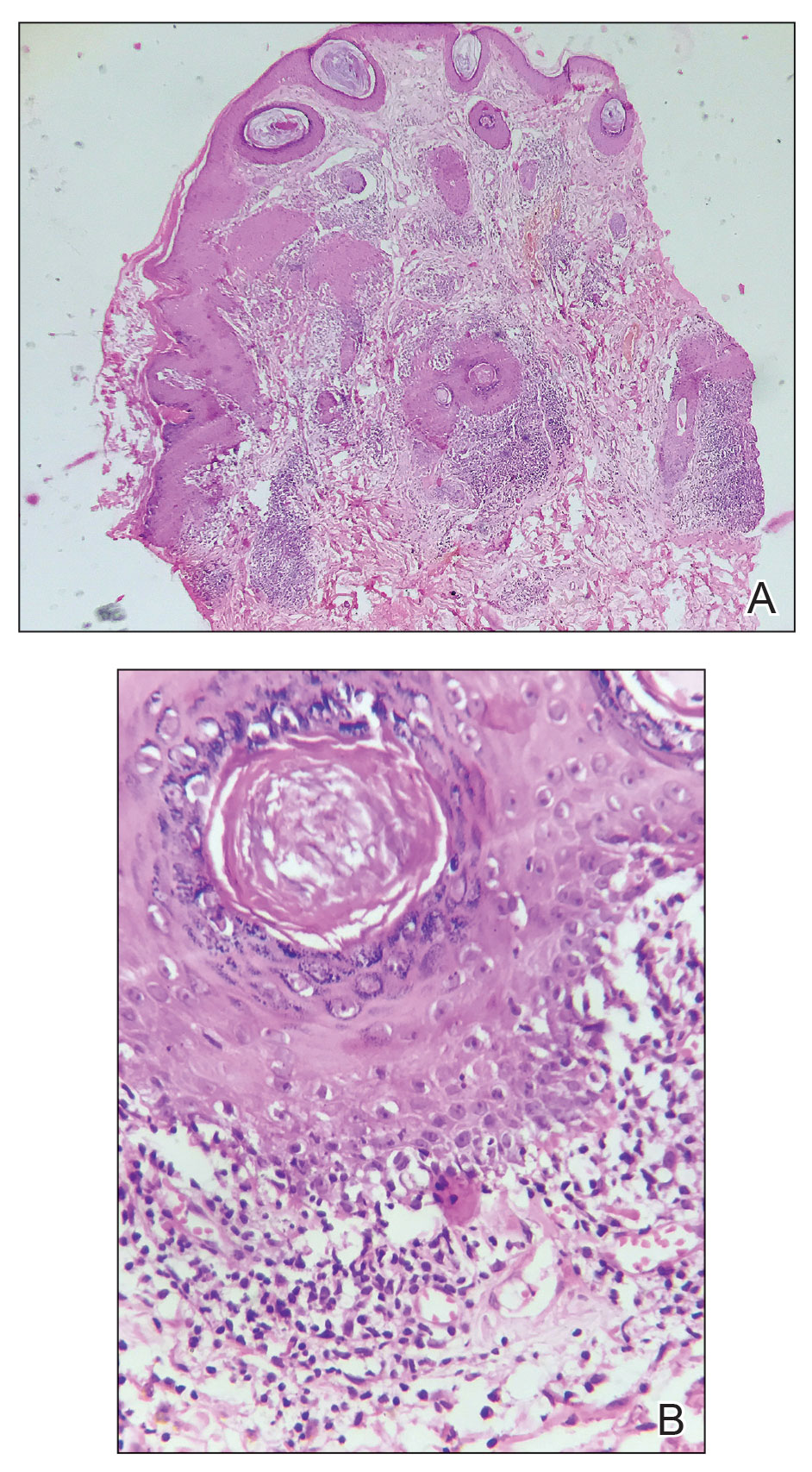

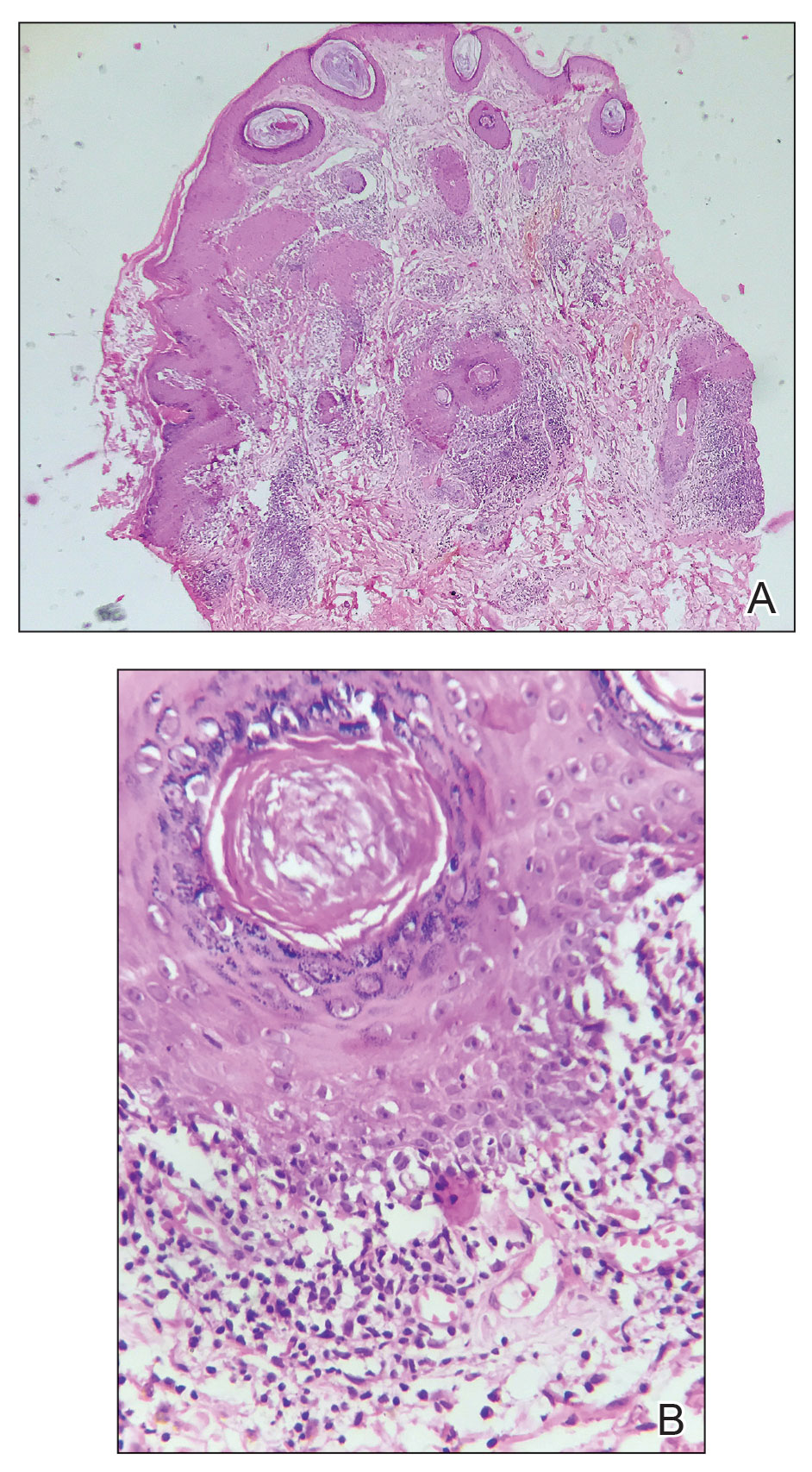

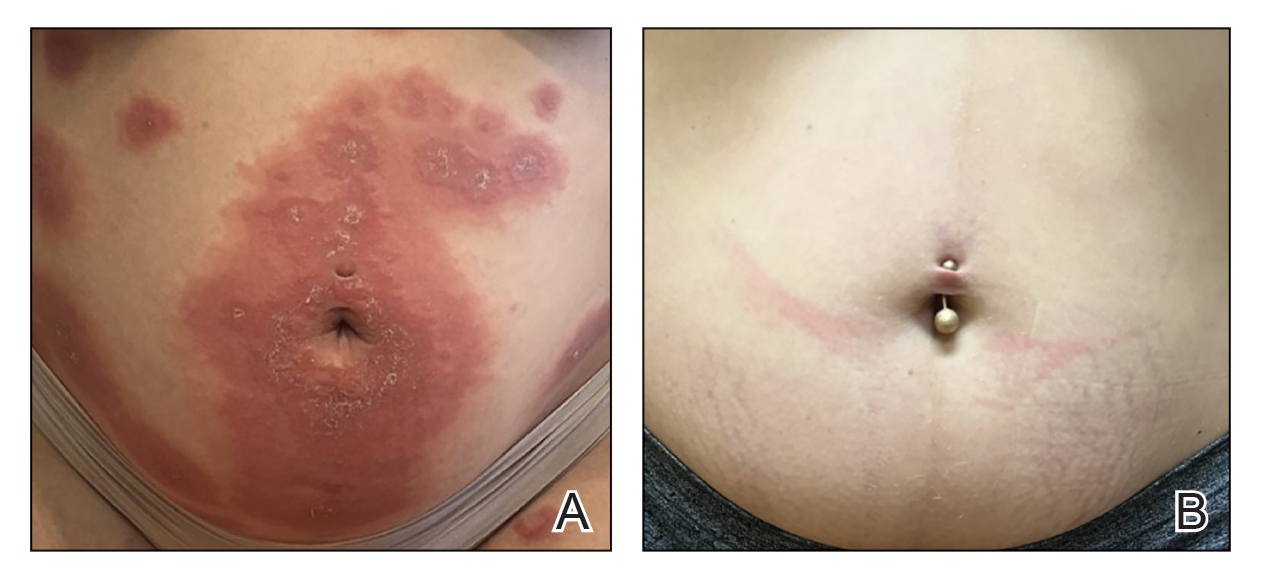

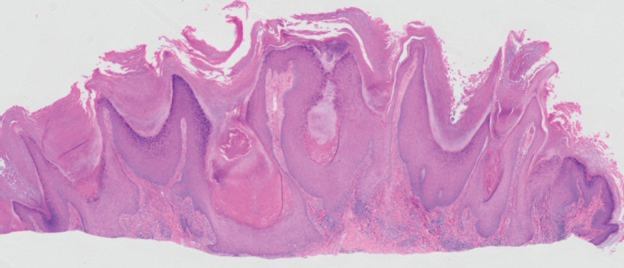

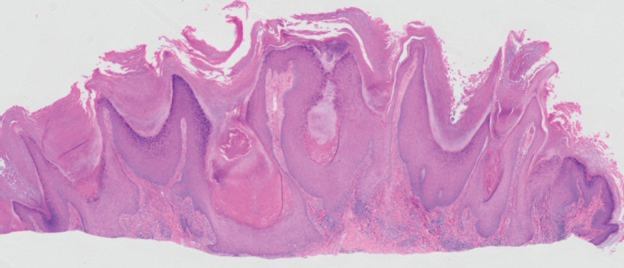

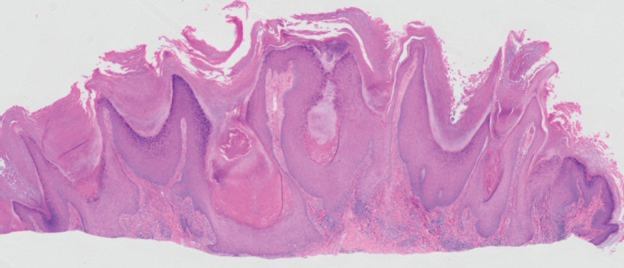

The biopsy revealed hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, follicular plugging, vacuolar interface dermatitis with apoptotic bodies, dyskeratotic keratinocytes, pigment incontinence, and melanophages. A perivascular, perifollicular, and periadnexal lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate was noted in the superficial and deep dermis (Figure). Based on the characteristic clinical morphology, dermoscopic features, and histopathology, a diagnosis of discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) was established. The patient was started on mometasone cream 0.1% and tacrolimus ointment 0.1% once daily, with strict recommendations for photoprotection. However, he subsequently was lost to follow-up, and treatment response could not be assessed.

Lupus erythematosus is a multisystemic autoimmune disease with a predilection for skin involvement that is characterized by the production of autoantibodies against nuclear antigens. Discoid lupus erythematosus is the predominant form of the disease, mostly affecting middle-aged women (female-to-male ratio, 4.1:1).1 Discoid lupus erythematosus usually manifests as well-demarcated, erythematous patches or plaques with partially adherent scales that extend into a patulous follicle. On removal, the scales show horny plugs underneath. This classic finding is known as the carpet tack sign.

As the lesions evolve, they expand with hyperpigmentation at the periphery as well as hypopigmentation, atrophy, scarring, and telangiectasias at the center.2 In our patient, the history of discharge and crusting of the lesion and the presence of slight central atrophy—all of which could be attributed to chronic application of topical medications such as corticosteroids, which can cause epidermal thinning, maceration, and secondary crust formation—raised clinical suspicion of cutaneous infections (eg, cutaneous leishmaniasis, lupus vulgaris) and squamous cell carcinoma. The presence of slightly raised margins upon clinical examination brought basal cell carcinoma (BCC) into the differential.

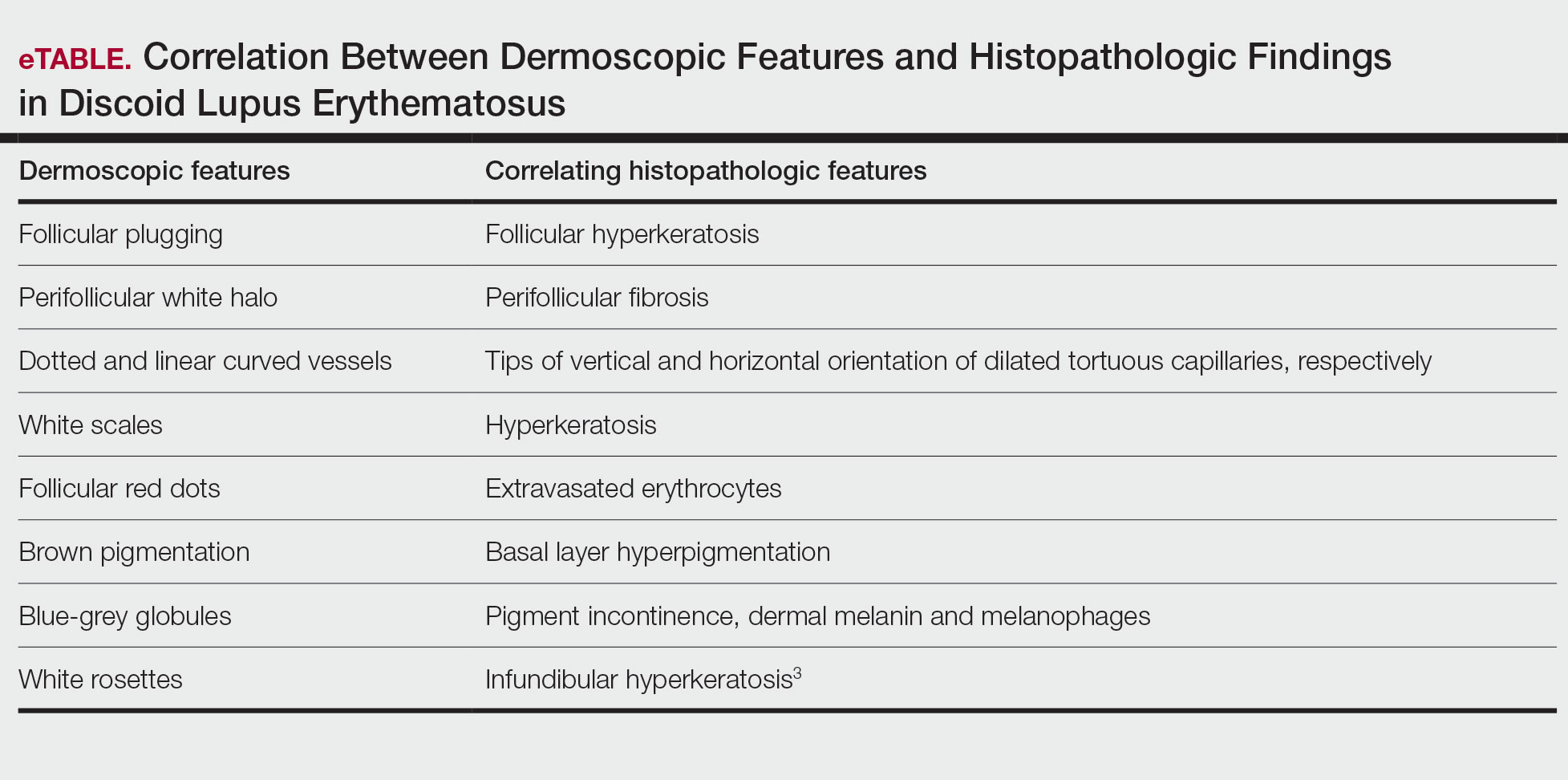

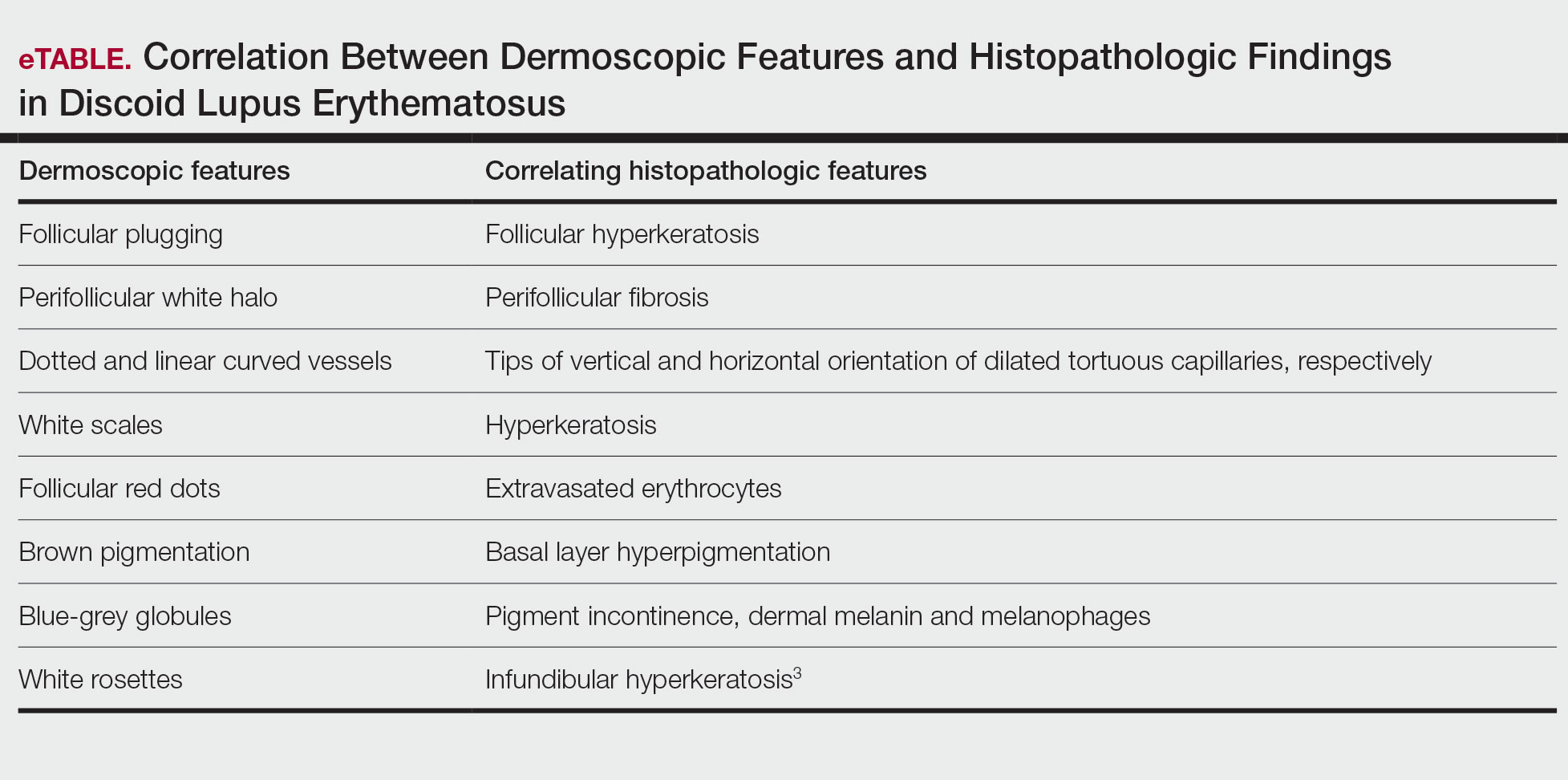

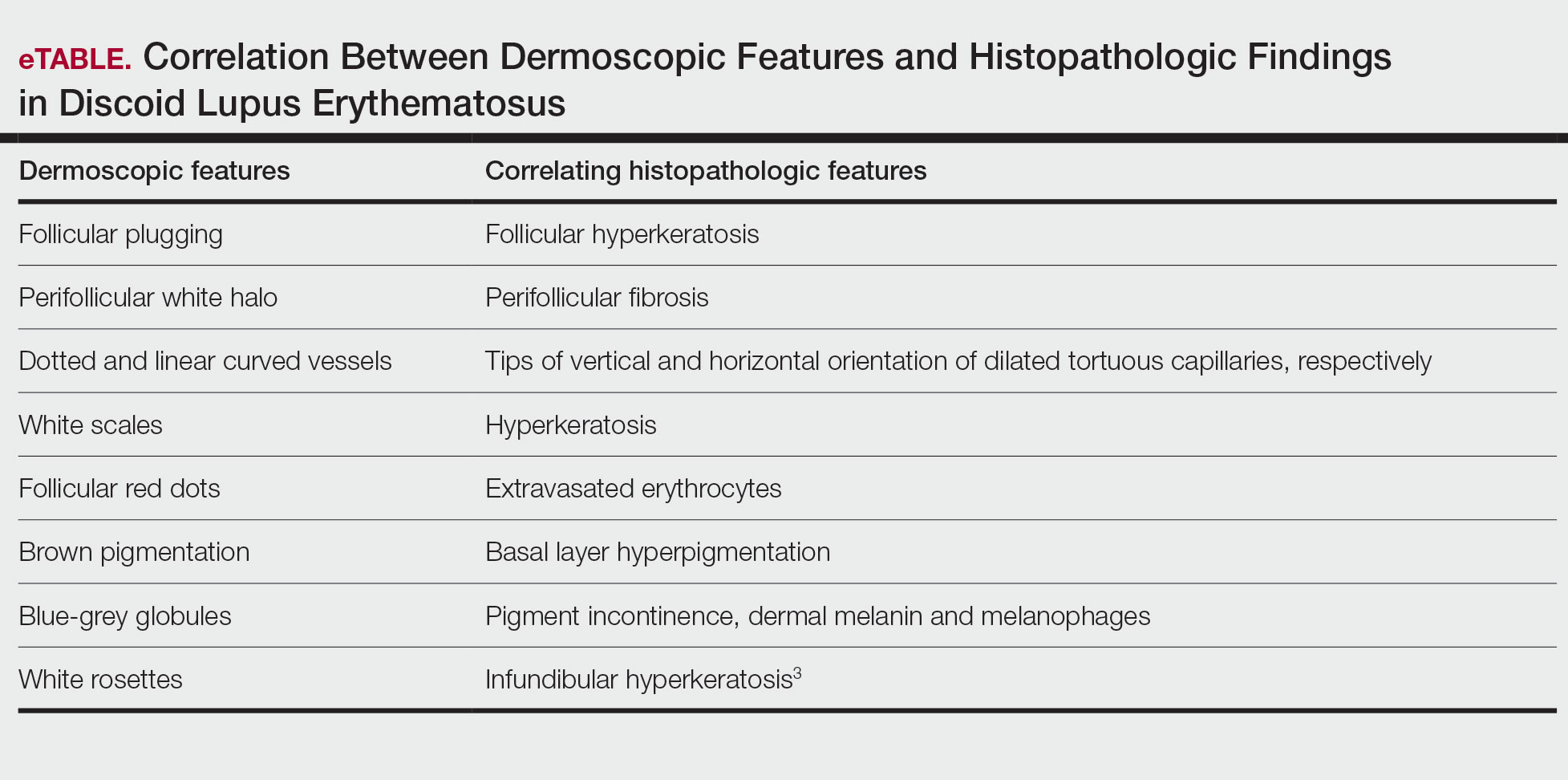

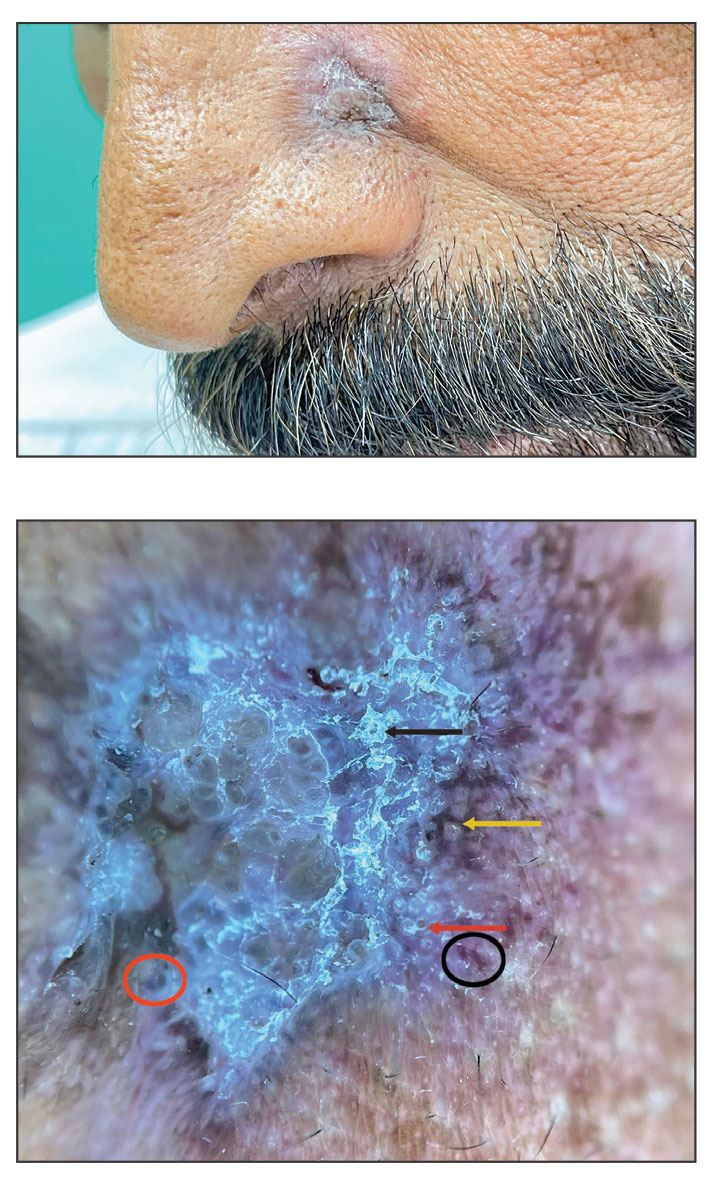

Dermoscopic features commonly seen in DLE reflect the pathologic findings. Follicular plugging and perifollicular white halos correspond to follicular hyperkeratosis and perifollicular fibrosis, respectively (eTable). Disease duration has been shown to alter the dermoscopic appearance of DLE with early active disease showing radially arranged arborizing blood vessels between perifollicular white halos along with follicular red dots, whereas lesions of longer duration display structureless white areas secondary to dermal fibrosis.3 Additionally, background erythema due to neoangiogenesis and dermal inflammation suggests that the disease is in its active state.

On dermoscopy, pigmentation structures such as brown dots, brown lines, and grey-brown dots and globules were seen more prominently in our patient with skin of color, making the underlying erythema more subtle than in patients with lighter skin types. Dotted and linear vessels also were seen in our patient, but not as prominently as typically is seen in lighter skin types.4

Lupus vulgaris was ruled out in our patient based on the absence of the typical orange to yellowish-orange background with vessels or any histopathologic evidence of epithelioid granulomas.5 Cutaneous leishmaniasis is characterized by polymorphic vascularization, erythema, follicular plugs, yellow-orange structureless areas with scales, and crusts on dermoscopy.6 Squamous cell carcinoma tends to show white structureless areas, looped vessels, and central keratin.7

Superficial BCC also appears as thin plaques or patches bound by a well-circumscribed, slightly raised, irregular margin. However, on dermoscopy, BCC typically exhibits spoke-wheel areas, arborizing vessels, comma vessels, and concentric structures.8

The clinical manifestations of crusting, discharge, and a raised border was atypical, probably owing to the long-term unsupervised application of topical medications, which made the initial diagnosis challenging. Therefore, various differential diagnoses were considered. Dermoscopic evaluation coupled with histology was performed, which ultimately confirmed the diagnosis of DLE.

- Gopalan G, Gopinath SR, Kothandaramasamy R, et al. A clinical and epidemiological study on discoid lupus erythematosus. Int J Res Dermatol 2018;4:396-402. doi:10.18203/issn.24554529.IntJRes Dermatol20183165

- McDaniel B, Sukumaran S, Koritala T, et al. Discoid lupus erythematosus. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing 2025. Updated August 28, 2023. Accessed October 15, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493145/

- Fathy H, Ghanim BM, Refat S, et al. Dermoscopic criteria of discoid lupus erythematosus: an observational cross-sectional study of 28 patients. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2022;88:360-366. doi:10.25259/IJDVL_207_19

- Ankad BS, Gupta A, Nikam BP, et al. Implications of dermoscopy and histopathological correlation in discoid lupus erythematosus in skin of color. Indian J Dermatol 2022;67:5‐11. doi:10.4103/ijd.ijd_591_21

- Jindal R, Chauhan P, Sethi S. Dermoscopy of the diverse spectrum of cutaneous tuberculosis in the skin of color. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2022;12:E2022203. doi:10.5826/dpc.1204a203

- Chauhan P, Adya KA. Dermatoscopy of cutaneous granulomatous disorders. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2021;12:34-44. doi:10.4103 /idoj.IDOJ_543_20.

- Rosendahl C, Cameron A, Argenziano G, et al. Dermoscopy of squamous cell carcinoma and keratoacanthoma. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1386-1392. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2012.2974.

- Vinciullo C, Mada V. Basal cell carcinoma. 10th ed. Wiley: Blackwell Science; 2024.

The biopsy revealed hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, follicular plugging, vacuolar interface dermatitis with apoptotic bodies, dyskeratotic keratinocytes, pigment incontinence, and melanophages. A perivascular, perifollicular, and periadnexal lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate was noted in the superficial and deep dermis (Figure). Based on the characteristic clinical morphology, dermoscopic features, and histopathology, a diagnosis of discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) was established. The patient was started on mometasone cream 0.1% and tacrolimus ointment 0.1% once daily, with strict recommendations for photoprotection. However, he subsequently was lost to follow-up, and treatment response could not be assessed.

Lupus erythematosus is a multisystemic autoimmune disease with a predilection for skin involvement that is characterized by the production of autoantibodies against nuclear antigens. Discoid lupus erythematosus is the predominant form of the disease, mostly affecting middle-aged women (female-to-male ratio, 4.1:1).1 Discoid lupus erythematosus usually manifests as well-demarcated, erythematous patches or plaques with partially adherent scales that extend into a patulous follicle. On removal, the scales show horny plugs underneath. This classic finding is known as the carpet tack sign.

As the lesions evolve, they expand with hyperpigmentation at the periphery as well as hypopigmentation, atrophy, scarring, and telangiectasias at the center.2 In our patient, the history of discharge and crusting of the lesion and the presence of slight central atrophy—all of which could be attributed to chronic application of topical medications such as corticosteroids, which can cause epidermal thinning, maceration, and secondary crust formation—raised clinical suspicion of cutaneous infections (eg, cutaneous leishmaniasis, lupus vulgaris) and squamous cell carcinoma. The presence of slightly raised margins upon clinical examination brought basal cell carcinoma (BCC) into the differential.

Dermoscopic features commonly seen in DLE reflect the pathologic findings. Follicular plugging and perifollicular white halos correspond to follicular hyperkeratosis and perifollicular fibrosis, respectively (eTable). Disease duration has been shown to alter the dermoscopic appearance of DLE with early active disease showing radially arranged arborizing blood vessels between perifollicular white halos along with follicular red dots, whereas lesions of longer duration display structureless white areas secondary to dermal fibrosis.3 Additionally, background erythema due to neoangiogenesis and dermal inflammation suggests that the disease is in its active state.

On dermoscopy, pigmentation structures such as brown dots, brown lines, and grey-brown dots and globules were seen more prominently in our patient with skin of color, making the underlying erythema more subtle than in patients with lighter skin types. Dotted and linear vessels also were seen in our patient, but not as prominently as typically is seen in lighter skin types.4

Lupus vulgaris was ruled out in our patient based on the absence of the typical orange to yellowish-orange background with vessels or any histopathologic evidence of epithelioid granulomas.5 Cutaneous leishmaniasis is characterized by polymorphic vascularization, erythema, follicular plugs, yellow-orange structureless areas with scales, and crusts on dermoscopy.6 Squamous cell carcinoma tends to show white structureless areas, looped vessels, and central keratin.7

Superficial BCC also appears as thin plaques or patches bound by a well-circumscribed, slightly raised, irregular margin. However, on dermoscopy, BCC typically exhibits spoke-wheel areas, arborizing vessels, comma vessels, and concentric structures.8

The clinical manifestations of crusting, discharge, and a raised border was atypical, probably owing to the long-term unsupervised application of topical medications, which made the initial diagnosis challenging. Therefore, various differential diagnoses were considered. Dermoscopic evaluation coupled with histology was performed, which ultimately confirmed the diagnosis of DLE.

The biopsy revealed hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, follicular plugging, vacuolar interface dermatitis with apoptotic bodies, dyskeratotic keratinocytes, pigment incontinence, and melanophages. A perivascular, perifollicular, and periadnexal lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate was noted in the superficial and deep dermis (Figure). Based on the characteristic clinical morphology, dermoscopic features, and histopathology, a diagnosis of discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) was established. The patient was started on mometasone cream 0.1% and tacrolimus ointment 0.1% once daily, with strict recommendations for photoprotection. However, he subsequently was lost to follow-up, and treatment response could not be assessed.

Lupus erythematosus is a multisystemic autoimmune disease with a predilection for skin involvement that is characterized by the production of autoantibodies against nuclear antigens. Discoid lupus erythematosus is the predominant form of the disease, mostly affecting middle-aged women (female-to-male ratio, 4.1:1).1 Discoid lupus erythematosus usually manifests as well-demarcated, erythematous patches or plaques with partially adherent scales that extend into a patulous follicle. On removal, the scales show horny plugs underneath. This classic finding is known as the carpet tack sign.

As the lesions evolve, they expand with hyperpigmentation at the periphery as well as hypopigmentation, atrophy, scarring, and telangiectasias at the center.2 In our patient, the history of discharge and crusting of the lesion and the presence of slight central atrophy—all of which could be attributed to chronic application of topical medications such as corticosteroids, which can cause epidermal thinning, maceration, and secondary crust formation—raised clinical suspicion of cutaneous infections (eg, cutaneous leishmaniasis, lupus vulgaris) and squamous cell carcinoma. The presence of slightly raised margins upon clinical examination brought basal cell carcinoma (BCC) into the differential.

Dermoscopic features commonly seen in DLE reflect the pathologic findings. Follicular plugging and perifollicular white halos correspond to follicular hyperkeratosis and perifollicular fibrosis, respectively (eTable). Disease duration has been shown to alter the dermoscopic appearance of DLE with early active disease showing radially arranged arborizing blood vessels between perifollicular white halos along with follicular red dots, whereas lesions of longer duration display structureless white areas secondary to dermal fibrosis.3 Additionally, background erythema due to neoangiogenesis and dermal inflammation suggests that the disease is in its active state.

On dermoscopy, pigmentation structures such as brown dots, brown lines, and grey-brown dots and globules were seen more prominently in our patient with skin of color, making the underlying erythema more subtle than in patients with lighter skin types. Dotted and linear vessels also were seen in our patient, but not as prominently as typically is seen in lighter skin types.4

Lupus vulgaris was ruled out in our patient based on the absence of the typical orange to yellowish-orange background with vessels or any histopathologic evidence of epithelioid granulomas.5 Cutaneous leishmaniasis is characterized by polymorphic vascularization, erythema, follicular plugs, yellow-orange structureless areas with scales, and crusts on dermoscopy.6 Squamous cell carcinoma tends to show white structureless areas, looped vessels, and central keratin.7

Superficial BCC also appears as thin plaques or patches bound by a well-circumscribed, slightly raised, irregular margin. However, on dermoscopy, BCC typically exhibits spoke-wheel areas, arborizing vessels, comma vessels, and concentric structures.8

The clinical manifestations of crusting, discharge, and a raised border was atypical, probably owing to the long-term unsupervised application of topical medications, which made the initial diagnosis challenging. Therefore, various differential diagnoses were considered. Dermoscopic evaluation coupled with histology was performed, which ultimately confirmed the diagnosis of DLE.

- Gopalan G, Gopinath SR, Kothandaramasamy R, et al. A clinical and epidemiological study on discoid lupus erythematosus. Int J Res Dermatol 2018;4:396-402. doi:10.18203/issn.24554529.IntJRes Dermatol20183165

- McDaniel B, Sukumaran S, Koritala T, et al. Discoid lupus erythematosus. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing 2025. Updated August 28, 2023. Accessed October 15, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493145/

- Fathy H, Ghanim BM, Refat S, et al. Dermoscopic criteria of discoid lupus erythematosus: an observational cross-sectional study of 28 patients. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2022;88:360-366. doi:10.25259/IJDVL_207_19

- Ankad BS, Gupta A, Nikam BP, et al. Implications of dermoscopy and histopathological correlation in discoid lupus erythematosus in skin of color. Indian J Dermatol 2022;67:5‐11. doi:10.4103/ijd.ijd_591_21

- Jindal R, Chauhan P, Sethi S. Dermoscopy of the diverse spectrum of cutaneous tuberculosis in the skin of color. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2022;12:E2022203. doi:10.5826/dpc.1204a203

- Chauhan P, Adya KA. Dermatoscopy of cutaneous granulomatous disorders. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2021;12:34-44. doi:10.4103 /idoj.IDOJ_543_20.

- Rosendahl C, Cameron A, Argenziano G, et al. Dermoscopy of squamous cell carcinoma and keratoacanthoma. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1386-1392. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2012.2974.

- Vinciullo C, Mada V. Basal cell carcinoma. 10th ed. Wiley: Blackwell Science; 2024.

- Gopalan G, Gopinath SR, Kothandaramasamy R, et al. A clinical and epidemiological study on discoid lupus erythematosus. Int J Res Dermatol 2018;4:396-402. doi:10.18203/issn.24554529.IntJRes Dermatol20183165

- McDaniel B, Sukumaran S, Koritala T, et al. Discoid lupus erythematosus. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing 2025. Updated August 28, 2023. Accessed October 15, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493145/

- Fathy H, Ghanim BM, Refat S, et al. Dermoscopic criteria of discoid lupus erythematosus: an observational cross-sectional study of 28 patients. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2022;88:360-366. doi:10.25259/IJDVL_207_19

- Ankad BS, Gupta A, Nikam BP, et al. Implications of dermoscopy and histopathological correlation in discoid lupus erythematosus in skin of color. Indian J Dermatol 2022;67:5‐11. doi:10.4103/ijd.ijd_591_21

- Jindal R, Chauhan P, Sethi S. Dermoscopy of the diverse spectrum of cutaneous tuberculosis in the skin of color. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2022;12:E2022203. doi:10.5826/dpc.1204a203

- Chauhan P, Adya KA. Dermatoscopy of cutaneous granulomatous disorders. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2021;12:34-44. doi:10.4103 /idoj.IDOJ_543_20.

- Rosendahl C, Cameron A, Argenziano G, et al. Dermoscopy of squamous cell carcinoma and keratoacanthoma. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1386-1392. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2012.2974.

- Vinciullo C, Mada V. Basal cell carcinoma. 10th ed. Wiley: Blackwell Science; 2024.

Solitary Plaque on the Nose

Solitary Plaque on the Nose

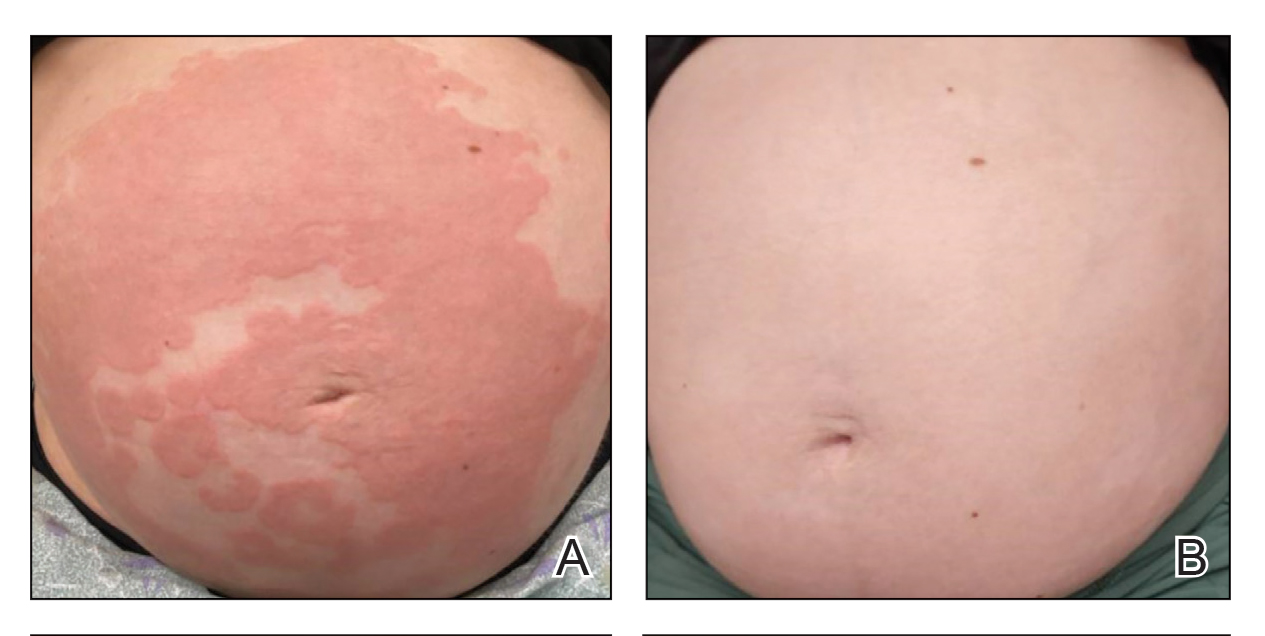

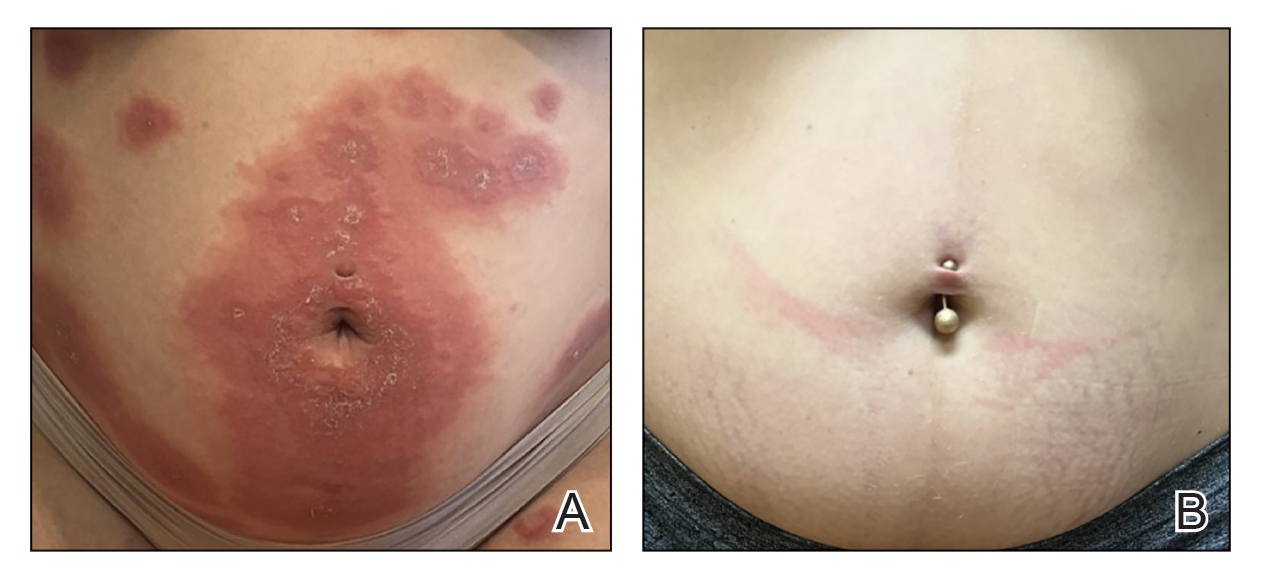

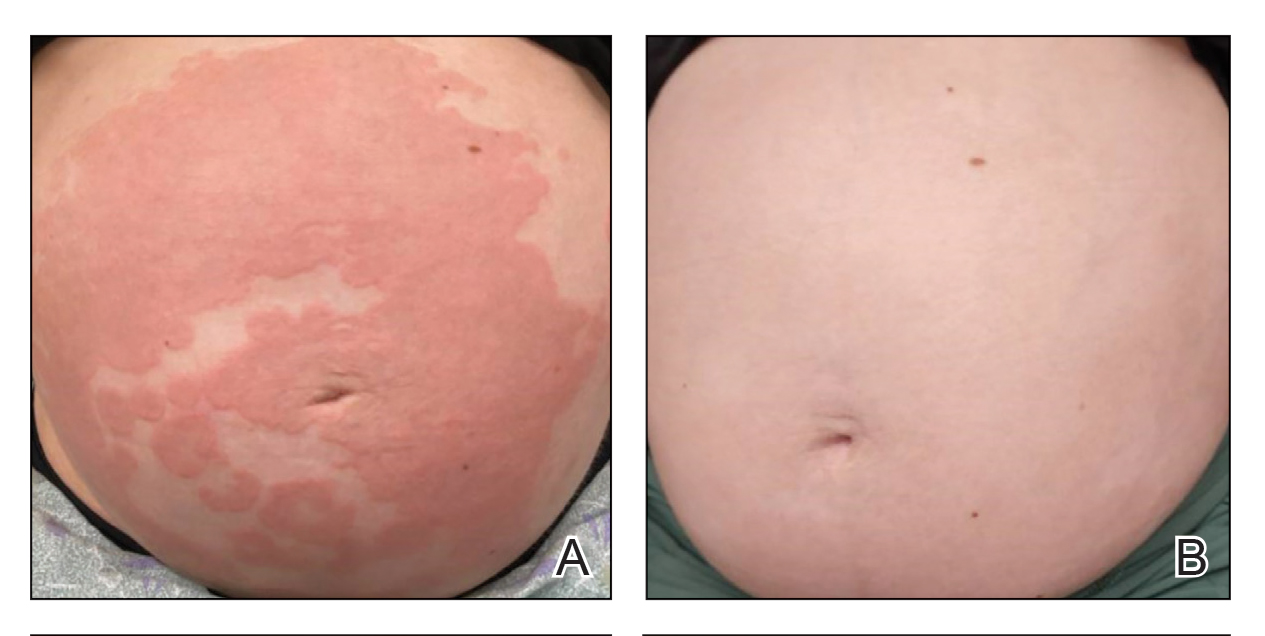

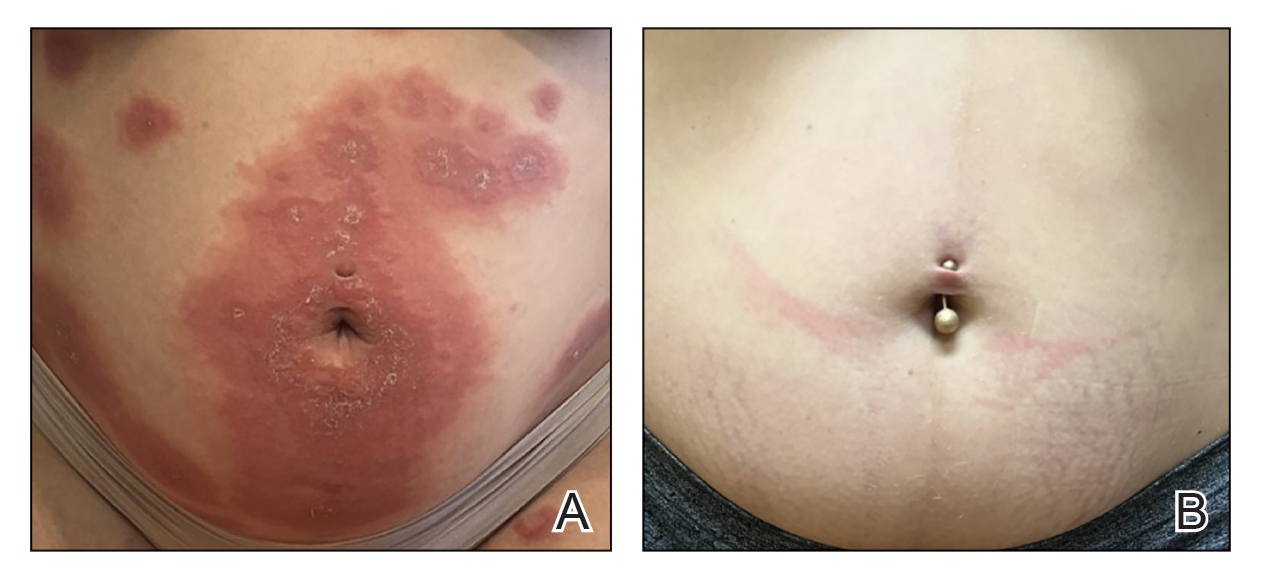

A 50-year-old Southeast Asian-Indian man presented to the dermatology clinic with a slightly elevated reddish-purple lesion on the left side of the nose accompanied by intense itching, occasional discharge, and crusting of 5 months’ duration. The patient reported applying multiple unknown topical agents initially prescribed to him by a physician; however, he subsequently continued applying these medications without regular follow-up visits. He had a history of smoking 2 packs per day for 25 years. His family history was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed a well-defined, 1.5×1.5-cm, nontender, scaly, erythematous to violaceous plaque with slightly raised margins, peripheral hyperpigmentation, and slight central atrophy on the left side of the nose. Dermoscopy revealed prominent follicles with a perifollicular halo (red arrow), white scales (black arrow), linear curved and dotted vessels (black circle), blue-grey globules (red circle), brown reticular lines (yellow arrow), and background erythema. General and systemic examination and routine laboratory workup were normal. A biopsy of the lesion was performed.

HPV Vaccine Reduces Immune Disease Risk in Women

TOPLINE: Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination is associated with reduced risks of rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and type 1 diabetes among females aged 9 to 45 years. The analysis of 208,638 vaccinated individuals shows particularly strong protective effects in those aged 9 to 26 years and recipients of 9-valent HPV vaccines.

METHODOLOGY:

Researchers analyzed data from the US Collaborative Network in TriNetX spanning January 1, 2018, to December 20, 2022, enrolling 208,638 females aged 9 to 45 years who received HPV vaccination and matching them with 208,638 unvaccinated individuals using propensity scores.

Analysis included Cox proportional hazard regression to estimate hazard ratios and 95% CIs for immune-mediated diseases, with subgroup analyses stratified by age, race, smoking, obesity, asthma, and HPV vaccine types.

Participants were monitored from 31 days up to 365 days following their respective index dates, with sensitivity analyses conducted to evaluate short-term outcomes and compare results with influenza virus vaccine recipients.

TAKEAWAY:

HPV vaccination demonstrated reduced risks for rheumatoid arthritis (hazard ratio [HR], 0.487; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.311-0.762), systemic lupus erythematosus (HR, 0.287; 95% CI, 0.179-0.460), and dermatomyositis (HR, 0.299; 95% CI, 0.098-0.908).

Recipients showed lower risks for inflammatory bowel disease (HR, 0.876; 95% CI, 0.811-0.946), celiac disease (HR, 0.400; 95% CI, 0.304-0.526), and type 1 diabetes (HR, 0.242; 95% CI, 0.184-0.318).

Subgroup analyses revealed significant risk reductions among females aged 9 to 26 years and those receiving 9-valent HPV vaccines compared to unvaccinated populations.

White and Black/African American individuals demonstrated reduced risks for various immune-mediated diseases, while Asians showed lower risks only for inflammatory bowel disease and overall immune-mediated diseases.

SOURCE: The study was led by Qianru Zhang, MD, Beijing Tsinghua Changgung Hospital in Beijing, China, James Cheng-Chung Wei, and Shiow-Ing Wang who contributed equally as first authors. It was published online in QJM: An International Journal of Medicine.

LIMITATIONS: According to the authors, research relying on Electronic Health Records (EHR) faced several constraints, including the absence of serial data on HPV antibody titers in vaccinated individuals and limited data regarding vaccination dosing numbers. Additionally, the current functionality of TriNetX prevented performing interaction terms in the statistical model for comprehensive subgroup analysis stratified by age, race, and vaccine types.

DISCLOSURES: The study received support from Chung Shan Medical University Hospital (Grant No. CSH-2023-E-001-Y2), Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital (KSVGH 113-117), National Science and Technology Council (NSTC 112-2314-B-075B-020), and KSVNSU112-008. The funders had no role in the study's design, conduct, data analysis, or manuscript approval.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

TOPLINE: Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination is associated with reduced risks of rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and type 1 diabetes among females aged 9 to 45 years. The analysis of 208,638 vaccinated individuals shows particularly strong protective effects in those aged 9 to 26 years and recipients of 9-valent HPV vaccines.

METHODOLOGY:

Researchers analyzed data from the US Collaborative Network in TriNetX spanning January 1, 2018, to December 20, 2022, enrolling 208,638 females aged 9 to 45 years who received HPV vaccination and matching them with 208,638 unvaccinated individuals using propensity scores.

Analysis included Cox proportional hazard regression to estimate hazard ratios and 95% CIs for immune-mediated diseases, with subgroup analyses stratified by age, race, smoking, obesity, asthma, and HPV vaccine types.

Participants were monitored from 31 days up to 365 days following their respective index dates, with sensitivity analyses conducted to evaluate short-term outcomes and compare results with influenza virus vaccine recipients.

TAKEAWAY:

HPV vaccination demonstrated reduced risks for rheumatoid arthritis (hazard ratio [HR], 0.487; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.311-0.762), systemic lupus erythematosus (HR, 0.287; 95% CI, 0.179-0.460), and dermatomyositis (HR, 0.299; 95% CI, 0.098-0.908).

Recipients showed lower risks for inflammatory bowel disease (HR, 0.876; 95% CI, 0.811-0.946), celiac disease (HR, 0.400; 95% CI, 0.304-0.526), and type 1 diabetes (HR, 0.242; 95% CI, 0.184-0.318).

Subgroup analyses revealed significant risk reductions among females aged 9 to 26 years and those receiving 9-valent HPV vaccines compared to unvaccinated populations.

White and Black/African American individuals demonstrated reduced risks for various immune-mediated diseases, while Asians showed lower risks only for inflammatory bowel disease and overall immune-mediated diseases.

SOURCE: The study was led by Qianru Zhang, MD, Beijing Tsinghua Changgung Hospital in Beijing, China, James Cheng-Chung Wei, and Shiow-Ing Wang who contributed equally as first authors. It was published online in QJM: An International Journal of Medicine.

LIMITATIONS: According to the authors, research relying on Electronic Health Records (EHR) faced several constraints, including the absence of serial data on HPV antibody titers in vaccinated individuals and limited data regarding vaccination dosing numbers. Additionally, the current functionality of TriNetX prevented performing interaction terms in the statistical model for comprehensive subgroup analysis stratified by age, race, and vaccine types.

DISCLOSURES: The study received support from Chung Shan Medical University Hospital (Grant No. CSH-2023-E-001-Y2), Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital (KSVGH 113-117), National Science and Technology Council (NSTC 112-2314-B-075B-020), and KSVNSU112-008. The funders had no role in the study's design, conduct, data analysis, or manuscript approval.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

TOPLINE: Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination is associated with reduced risks of rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and type 1 diabetes among females aged 9 to 45 years. The analysis of 208,638 vaccinated individuals shows particularly strong protective effects in those aged 9 to 26 years and recipients of 9-valent HPV vaccines.

METHODOLOGY:

Researchers analyzed data from the US Collaborative Network in TriNetX spanning January 1, 2018, to December 20, 2022, enrolling 208,638 females aged 9 to 45 years who received HPV vaccination and matching them with 208,638 unvaccinated individuals using propensity scores.

Analysis included Cox proportional hazard regression to estimate hazard ratios and 95% CIs for immune-mediated diseases, with subgroup analyses stratified by age, race, smoking, obesity, asthma, and HPV vaccine types.

Participants were monitored from 31 days up to 365 days following their respective index dates, with sensitivity analyses conducted to evaluate short-term outcomes and compare results with influenza virus vaccine recipients.

TAKEAWAY:

HPV vaccination demonstrated reduced risks for rheumatoid arthritis (hazard ratio [HR], 0.487; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.311-0.762), systemic lupus erythematosus (HR, 0.287; 95% CI, 0.179-0.460), and dermatomyositis (HR, 0.299; 95% CI, 0.098-0.908).

Recipients showed lower risks for inflammatory bowel disease (HR, 0.876; 95% CI, 0.811-0.946), celiac disease (HR, 0.400; 95% CI, 0.304-0.526), and type 1 diabetes (HR, 0.242; 95% CI, 0.184-0.318).

Subgroup analyses revealed significant risk reductions among females aged 9 to 26 years and those receiving 9-valent HPV vaccines compared to unvaccinated populations.

White and Black/African American individuals demonstrated reduced risks for various immune-mediated diseases, while Asians showed lower risks only for inflammatory bowel disease and overall immune-mediated diseases.

SOURCE: The study was led by Qianru Zhang, MD, Beijing Tsinghua Changgung Hospital in Beijing, China, James Cheng-Chung Wei, and Shiow-Ing Wang who contributed equally as first authors. It was published online in QJM: An International Journal of Medicine.

LIMITATIONS: According to the authors, research relying on Electronic Health Records (EHR) faced several constraints, including the absence of serial data on HPV antibody titers in vaccinated individuals and limited data regarding vaccination dosing numbers. Additionally, the current functionality of TriNetX prevented performing interaction terms in the statistical model for comprehensive subgroup analysis stratified by age, race, and vaccine types.

DISCLOSURES: The study received support from Chung Shan Medical University Hospital (Grant No. CSH-2023-E-001-Y2), Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital (KSVGH 113-117), National Science and Technology Council (NSTC 112-2314-B-075B-020), and KSVNSU112-008. The funders had no role in the study's design, conduct, data analysis, or manuscript approval.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

Consider Cultural Practices and Barriers to Care When Treating Alopecia Areata

Consider Cultural Practices and Barriers to Care When Treating Alopecia Areata

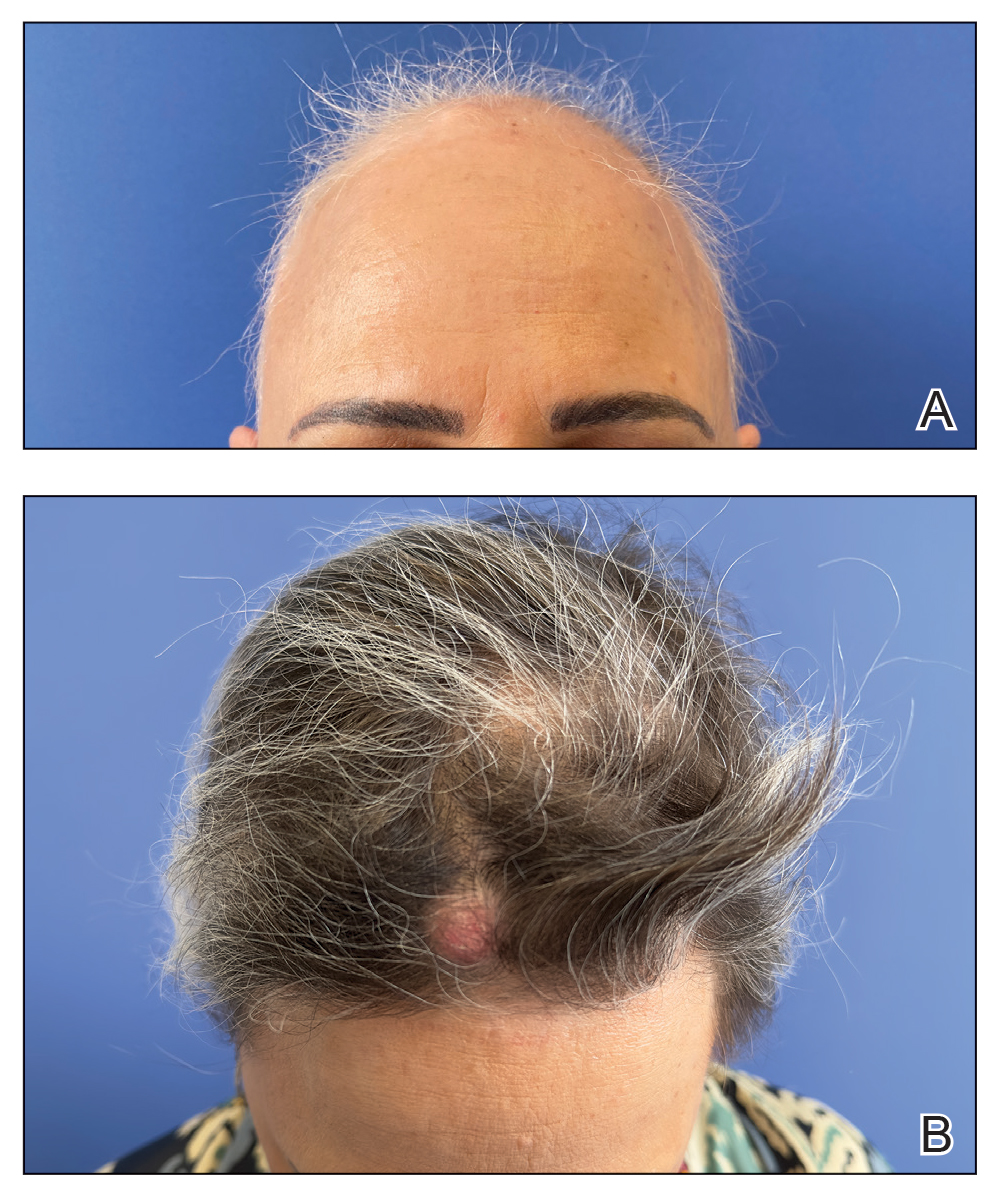

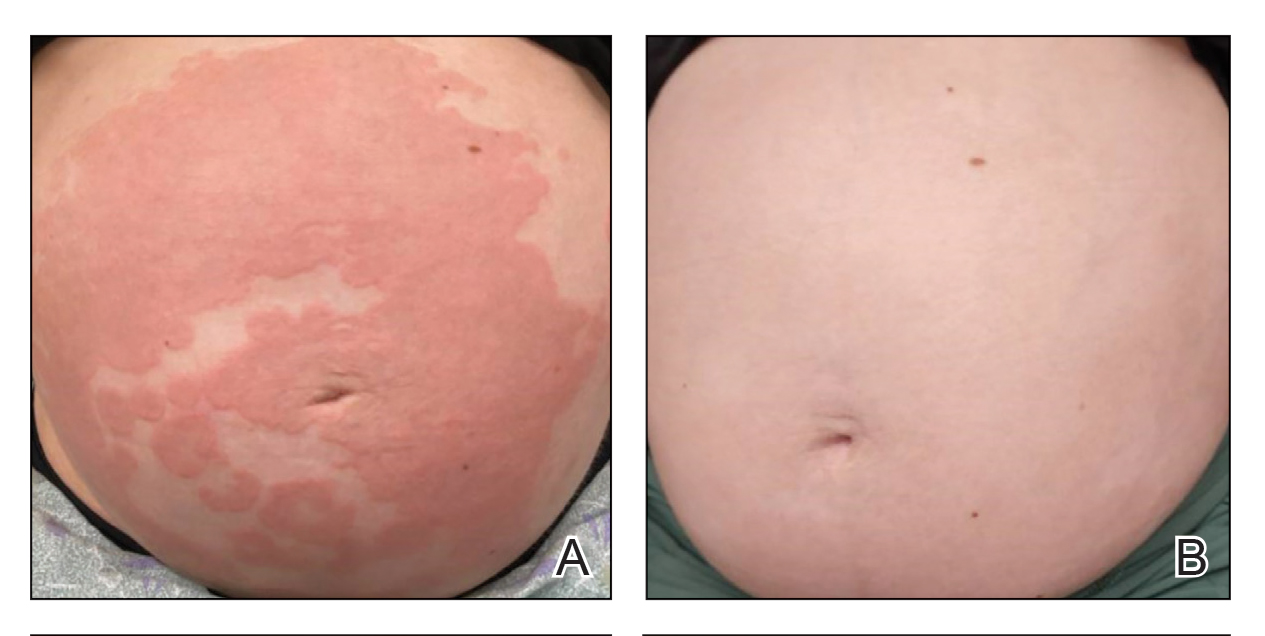

The Comparison

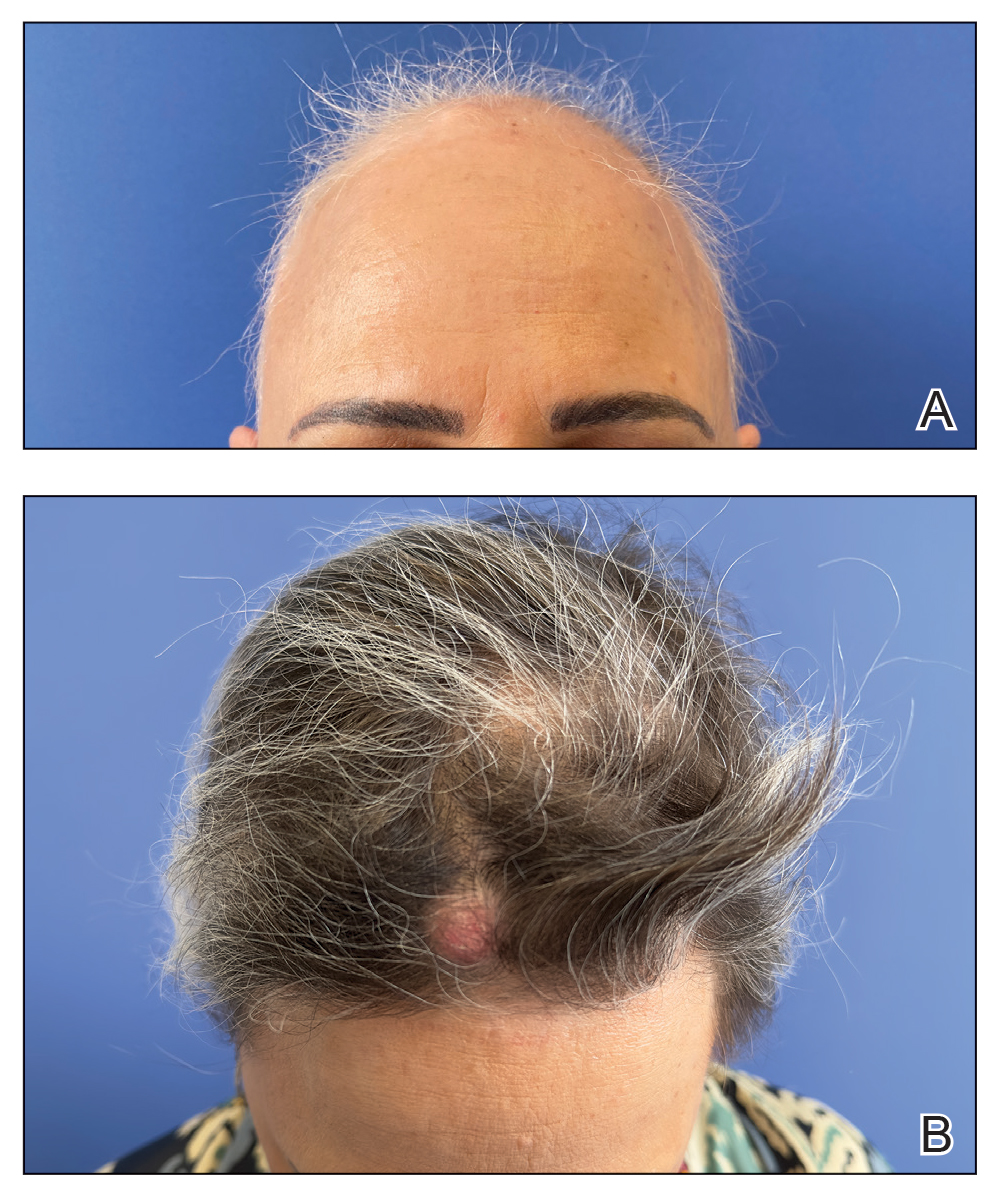

A. Alopecia areata in a young girl with a lighter skin tone. The fine white vellus hairs are signs of regrowth.

B. Alopecia areata in a 49-year-old man with tightly coiled hair and darker skin tone. Coiled white hairs are noted in the alopecia patches.

young girl with a lighter skin

tone. The fine white vellus

hairs are signs of regrowth. Photographs courtesy of

Richard P. Usatine, MD.

49-year-old man with tightly

coiled hair and darker skin

tone. Coiled white hairs

are noted in the alopecia

patches. Photographs courtesy of

Richard P. Usatine, MD.

Alopecia areata (AA) is a common autoimmune condition characterized by hair loss resulting from a T cell–mediated attack on the hair follicles. It manifests as nonscarring patches of hair loss on the scalp, eyebrows, eyelashes, and beard area as well as more extensive complete loss of scalp and body hair. While AA may affect individuals of any age, most patients develop their first patch(es) of hair loss during childhood.1 The treatment landscape for AA has evolved considerably in recent years, but barriers to access to newer treatments persist.

Epidemiology

AA is most prevalent among pediatric and adult individuals of African, Asian, or Hispanic/Latino descent.2-4 In some studies, Black individuals had higher odds and Asian individuals had lower odds of developing AA, while other studies have reported the highest standardized prevalence among Asian individuals.5 In the United States, AA affects about 1.47% of adults and as many as 0.11% of children.6-8 In Black patients, AA often manifests early with a female predominance.5

AA frequently is associated with autoimmune comorbidities, the most common being thyroid disease.3,5 In Black patients, AA is associated with more atopic comorbidities, including asthma, atopic dermatitis, and allergic rhinitis.5

Key Clinical Features

AA clinically manifests similarly across different skin tones; however, in patients with more tightly coiled or curly hair, the extent of scalp hair loss may be underestimated without a full examination. Culturally sensitive approaches to hair and scalp evaluation are essential, especially for Black women, whose hair care practices and scalp conditions may be overlooked or misunderstood during visits to evaluate hair loss. A thoughtful history and gentle examination of the hair and scalp that considers hair texture, cultural practices such as head coverings (eg, headwraps, turbans, hijabs), use of hair adornments (eg, clips, beads, bows), traditional braiding, and use of natural oils or herbal treatments, as well as styling methods including tight hairstyles, use of heat styling tools (eg, flat irons, curling irons), chemical application (eg, straighteners, hair color), and washing or styling frequency can improve diagnostic accuracy and help build trust in the patient-provider relationship.

Classic signs of AA visualized with dermoscopy include yellow and/or black dots on the scalp and exclamation point hairs. The appearance of fine white vellus hairs within the alopecic patches also may indicate early regrowth. On scalp trichoscopy, black dots are more prominent, and yellow dots are less prominent, in individuals with darker skin tones vs lighter skin tones.9

Worth Noting

In addition to a full examination of the scalp, documenting the extent of hair loss using validated severity scales, including the severity of alopecia tool (SALT), AA severity index (AASI), clinician-reported outcome assessment, and patient-reported outcome measures, can standardize disease severity assessment, facilitate timely insurance or medication approvals, and support objective tracking of treatment response, which may ultimately enhance access to care.10

Prompt treatment of AA is essential. Not surprisingly, patients given a diagnosis of AA may experience considerable emotional and psychological distress—regardless of the extent of the loss.11 Treatment options include mid- to high-potency topical or intralesional corticosteroids and newer and more targeted systemic options, including 3 Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors—baricitinib, ritlecitinib, and deuruxolitinib—for more extensive disease.12 Treatment with intralesional corticosteroids may cause transient hypopigmentation, which may be more noticeable in patients with darker skin tones. Delays in treatment with JAK inhibitors can lead to a less-than-optimal response. Of the 3 JAK inhibitors that are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for AA, only ritlecitinib is approved for children 12 years and older, leaving a therapeutic gap for younger patients that often leads to uncomfortable scalp injections, delayed or no treatment, off-label use of JAK inhibitors as well as the pairing of off-label dupilumab with oral minoxidil.12

Based on adult data, patients with severe disease and a shorter duration of hair loss (ie, < 4 years) tend to respond better to JAK inhibitors than those experiencing hair loss for longer periods. Also, those with more severe AA tend to have poorer outcomes than those with less severe disease.13 If treatment proves less than optimal, wigs and hair pieces may need to be considered. It is worth noting that some insurance companies will cover the cost of wigs for patients when prescribed as cranial prostheses.

Health Disparity Highlight

Health disparities in AA can be influenced by socioeconomic status and access to care. Patients from lower-income backgrounds often face barriers to accessing dermatologic care and treatments such as JAK inhibitors, which may remain inaccessible due to high costs and insurance limitations.14 These barriers can intersect with other factors such as age, sex, and race, potentially exacerbating disparities. Women with skin of color in underserved communities may experience delayed diagnosis, limited treatment options, and greater psychosocial distress from hair loss.14 Addressing these inequities requires advocacy, education for both patients and clinicians, and improved access to treatment to ensure comprehensive care for all patients.

- Kara T, Topkarcı Z. Interactions between posttraumatic stress disorder and alopecia areata in child with trauma exposure: two case reports. Int J Trichology. 2018;10:131-134. doi:10.4103/ijt.ijt_2_18

- Sy N, Mastacouris N, Strunk A, et al. Overall and racial and ethnic subgroup prevalences of alopecia areata, alopecia totalis, and alopecia universalis. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:419-423.

- Lee H, Jung SJ, Patel AB, et al. Racial characteristics of alopecia areata in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1064-1070.

- Feaster B, McMichael AJ. Epidemiology of alopecia areata in Black patients: a retrospective chart review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:1121-1123.

- Lee HH, Gwillim E, Patel KR, et al. Epidemiology of alopecia areata, ophiasis, totalis, and universalis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:675-682.

- Mostaghimi A, Gao W, Ray M, et al. Trends in prevalence and incidence of alopecia areata, alopecia totalis, and alopecia universalis among adults and children in a US employer-sponsored insured population. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:411-418.

- Adhanom R, Ansbro B, Castelo-Soccio L. Epidemiology of pediatric alopecia areata. Pediatr Dermatol. 2025;42 suppl 1(suppl 1):12-23.

- Karampinis E, Toli O, Georgopoulou KE, et al. Exploring pediatric dermatology in skin of color: focus on dermoscopy. Life (Basel). 2024;14:1604.

- King BA, Senna MM, Ohyama M, et al. Defining severity in alopecia areata: current perspectives and a multidimensional framework. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022;12:825-834.

- Toussi A, Barton VR, Le ST, et al. Psychosocial and psychiatric comorbidities and health-related quality of life in alopecia areata: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:162-175.

- Kalil L, Welch D, Heath CR, et al. Systemic therapies for pediatric alopecia areata. Pediatr Dermatol. 2025;42 suppl 1:36-42.

- King BA, Craiglow BG. Janus kinase inhibitors for alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:S29-S32.

- Klein EJ, Taiwò D, Kakpovbia E, et al. Disparities in Janus kinase inhibitor access for alopecia areata: a retrospective analysis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2024;10:E155.

- McKenzie PL, Maltenfort M, Bruckner AL, et al. Evaluation of the prevalence and incidence of pediatric alopecia areata using electronic health record data. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:547-551. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.0351

The Comparison

A. Alopecia areata in a young girl with a lighter skin tone. The fine white vellus hairs are signs of regrowth.

B. Alopecia areata in a 49-year-old man with tightly coiled hair and darker skin tone. Coiled white hairs are noted in the alopecia patches.

young girl with a lighter skin

tone. The fine white vellus

hairs are signs of regrowth. Photographs courtesy of

Richard P. Usatine, MD.

49-year-old man with tightly

coiled hair and darker skin

tone. Coiled white hairs

are noted in the alopecia

patches. Photographs courtesy of

Richard P. Usatine, MD.

Alopecia areata (AA) is a common autoimmune condition characterized by hair loss resulting from a T cell–mediated attack on the hair follicles. It manifests as nonscarring patches of hair loss on the scalp, eyebrows, eyelashes, and beard area as well as more extensive complete loss of scalp and body hair. While AA may affect individuals of any age, most patients develop their first patch(es) of hair loss during childhood.1 The treatment landscape for AA has evolved considerably in recent years, but barriers to access to newer treatments persist.

Epidemiology

AA is most prevalent among pediatric and adult individuals of African, Asian, or Hispanic/Latino descent.2-4 In some studies, Black individuals had higher odds and Asian individuals had lower odds of developing AA, while other studies have reported the highest standardized prevalence among Asian individuals.5 In the United States, AA affects about 1.47% of adults and as many as 0.11% of children.6-8 In Black patients, AA often manifests early with a female predominance.5

AA frequently is associated with autoimmune comorbidities, the most common being thyroid disease.3,5 In Black patients, AA is associated with more atopic comorbidities, including asthma, atopic dermatitis, and allergic rhinitis.5

Key Clinical Features

AA clinically manifests similarly across different skin tones; however, in patients with more tightly coiled or curly hair, the extent of scalp hair loss may be underestimated without a full examination. Culturally sensitive approaches to hair and scalp evaluation are essential, especially for Black women, whose hair care practices and scalp conditions may be overlooked or misunderstood during visits to evaluate hair loss. A thoughtful history and gentle examination of the hair and scalp that considers hair texture, cultural practices such as head coverings (eg, headwraps, turbans, hijabs), use of hair adornments (eg, clips, beads, bows), traditional braiding, and use of natural oils or herbal treatments, as well as styling methods including tight hairstyles, use of heat styling tools (eg, flat irons, curling irons), chemical application (eg, straighteners, hair color), and washing or styling frequency can improve diagnostic accuracy and help build trust in the patient-provider relationship.

Classic signs of AA visualized with dermoscopy include yellow and/or black dots on the scalp and exclamation point hairs. The appearance of fine white vellus hairs within the alopecic patches also may indicate early regrowth. On scalp trichoscopy, black dots are more prominent, and yellow dots are less prominent, in individuals with darker skin tones vs lighter skin tones.9

Worth Noting

In addition to a full examination of the scalp, documenting the extent of hair loss using validated severity scales, including the severity of alopecia tool (SALT), AA severity index (AASI), clinician-reported outcome assessment, and patient-reported outcome measures, can standardize disease severity assessment, facilitate timely insurance or medication approvals, and support objective tracking of treatment response, which may ultimately enhance access to care.10

Prompt treatment of AA is essential. Not surprisingly, patients given a diagnosis of AA may experience considerable emotional and psychological distress—regardless of the extent of the loss.11 Treatment options include mid- to high-potency topical or intralesional corticosteroids and newer and more targeted systemic options, including 3 Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors—baricitinib, ritlecitinib, and deuruxolitinib—for more extensive disease.12 Treatment with intralesional corticosteroids may cause transient hypopigmentation, which may be more noticeable in patients with darker skin tones. Delays in treatment with JAK inhibitors can lead to a less-than-optimal response. Of the 3 JAK inhibitors that are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for AA, only ritlecitinib is approved for children 12 years and older, leaving a therapeutic gap for younger patients that often leads to uncomfortable scalp injections, delayed or no treatment, off-label use of JAK inhibitors as well as the pairing of off-label dupilumab with oral minoxidil.12

Based on adult data, patients with severe disease and a shorter duration of hair loss (ie, < 4 years) tend to respond better to JAK inhibitors than those experiencing hair loss for longer periods. Also, those with more severe AA tend to have poorer outcomes than those with less severe disease.13 If treatment proves less than optimal, wigs and hair pieces may need to be considered. It is worth noting that some insurance companies will cover the cost of wigs for patients when prescribed as cranial prostheses.

Health Disparity Highlight

Health disparities in AA can be influenced by socioeconomic status and access to care. Patients from lower-income backgrounds often face barriers to accessing dermatologic care and treatments such as JAK inhibitors, which may remain inaccessible due to high costs and insurance limitations.14 These barriers can intersect with other factors such as age, sex, and race, potentially exacerbating disparities. Women with skin of color in underserved communities may experience delayed diagnosis, limited treatment options, and greater psychosocial distress from hair loss.14 Addressing these inequities requires advocacy, education for both patients and clinicians, and improved access to treatment to ensure comprehensive care for all patients.

The Comparison

A. Alopecia areata in a young girl with a lighter skin tone. The fine white vellus hairs are signs of regrowth.

B. Alopecia areata in a 49-year-old man with tightly coiled hair and darker skin tone. Coiled white hairs are noted in the alopecia patches.

young girl with a lighter skin

tone. The fine white vellus

hairs are signs of regrowth. Photographs courtesy of

Richard P. Usatine, MD.

49-year-old man with tightly

coiled hair and darker skin

tone. Coiled white hairs

are noted in the alopecia

patches. Photographs courtesy of

Richard P. Usatine, MD.

Alopecia areata (AA) is a common autoimmune condition characterized by hair loss resulting from a T cell–mediated attack on the hair follicles. It manifests as nonscarring patches of hair loss on the scalp, eyebrows, eyelashes, and beard area as well as more extensive complete loss of scalp and body hair. While AA may affect individuals of any age, most patients develop their first patch(es) of hair loss during childhood.1 The treatment landscape for AA has evolved considerably in recent years, but barriers to access to newer treatments persist.

Epidemiology

AA is most prevalent among pediatric and adult individuals of African, Asian, or Hispanic/Latino descent.2-4 In some studies, Black individuals had higher odds and Asian individuals had lower odds of developing AA, while other studies have reported the highest standardized prevalence among Asian individuals.5 In the United States, AA affects about 1.47% of adults and as many as 0.11% of children.6-8 In Black patients, AA often manifests early with a female predominance.5

AA frequently is associated with autoimmune comorbidities, the most common being thyroid disease.3,5 In Black patients, AA is associated with more atopic comorbidities, including asthma, atopic dermatitis, and allergic rhinitis.5

Key Clinical Features

AA clinically manifests similarly across different skin tones; however, in patients with more tightly coiled or curly hair, the extent of scalp hair loss may be underestimated without a full examination. Culturally sensitive approaches to hair and scalp evaluation are essential, especially for Black women, whose hair care practices and scalp conditions may be overlooked or misunderstood during visits to evaluate hair loss. A thoughtful history and gentle examination of the hair and scalp that considers hair texture, cultural practices such as head coverings (eg, headwraps, turbans, hijabs), use of hair adornments (eg, clips, beads, bows), traditional braiding, and use of natural oils or herbal treatments, as well as styling methods including tight hairstyles, use of heat styling tools (eg, flat irons, curling irons), chemical application (eg, straighteners, hair color), and washing or styling frequency can improve diagnostic accuracy and help build trust in the patient-provider relationship.

Classic signs of AA visualized with dermoscopy include yellow and/or black dots on the scalp and exclamation point hairs. The appearance of fine white vellus hairs within the alopecic patches also may indicate early regrowth. On scalp trichoscopy, black dots are more prominent, and yellow dots are less prominent, in individuals with darker skin tones vs lighter skin tones.9

Worth Noting

In addition to a full examination of the scalp, documenting the extent of hair loss using validated severity scales, including the severity of alopecia tool (SALT), AA severity index (AASI), clinician-reported outcome assessment, and patient-reported outcome measures, can standardize disease severity assessment, facilitate timely insurance or medication approvals, and support objective tracking of treatment response, which may ultimately enhance access to care.10

Prompt treatment of AA is essential. Not surprisingly, patients given a diagnosis of AA may experience considerable emotional and psychological distress—regardless of the extent of the loss.11 Treatment options include mid- to high-potency topical or intralesional corticosteroids and newer and more targeted systemic options, including 3 Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors—baricitinib, ritlecitinib, and deuruxolitinib—for more extensive disease.12 Treatment with intralesional corticosteroids may cause transient hypopigmentation, which may be more noticeable in patients with darker skin tones. Delays in treatment with JAK inhibitors can lead to a less-than-optimal response. Of the 3 JAK inhibitors that are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for AA, only ritlecitinib is approved for children 12 years and older, leaving a therapeutic gap for younger patients that often leads to uncomfortable scalp injections, delayed or no treatment, off-label use of JAK inhibitors as well as the pairing of off-label dupilumab with oral minoxidil.12

Based on adult data, patients with severe disease and a shorter duration of hair loss (ie, < 4 years) tend to respond better to JAK inhibitors than those experiencing hair loss for longer periods. Also, those with more severe AA tend to have poorer outcomes than those with less severe disease.13 If treatment proves less than optimal, wigs and hair pieces may need to be considered. It is worth noting that some insurance companies will cover the cost of wigs for patients when prescribed as cranial prostheses.

Health Disparity Highlight

Health disparities in AA can be influenced by socioeconomic status and access to care. Patients from lower-income backgrounds often face barriers to accessing dermatologic care and treatments such as JAK inhibitors, which may remain inaccessible due to high costs and insurance limitations.14 These barriers can intersect with other factors such as age, sex, and race, potentially exacerbating disparities. Women with skin of color in underserved communities may experience delayed diagnosis, limited treatment options, and greater psychosocial distress from hair loss.14 Addressing these inequities requires advocacy, education for both patients and clinicians, and improved access to treatment to ensure comprehensive care for all patients.

- Kara T, Topkarcı Z. Interactions between posttraumatic stress disorder and alopecia areata in child with trauma exposure: two case reports. Int J Trichology. 2018;10:131-134. doi:10.4103/ijt.ijt_2_18

- Sy N, Mastacouris N, Strunk A, et al. Overall and racial and ethnic subgroup prevalences of alopecia areata, alopecia totalis, and alopecia universalis. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:419-423.

- Lee H, Jung SJ, Patel AB, et al. Racial characteristics of alopecia areata in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1064-1070.

- Feaster B, McMichael AJ. Epidemiology of alopecia areata in Black patients: a retrospective chart review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:1121-1123.

- Lee HH, Gwillim E, Patel KR, et al. Epidemiology of alopecia areata, ophiasis, totalis, and universalis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:675-682.

- Mostaghimi A, Gao W, Ray M, et al. Trends in prevalence and incidence of alopecia areata, alopecia totalis, and alopecia universalis among adults and children in a US employer-sponsored insured population. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:411-418.

- Adhanom R, Ansbro B, Castelo-Soccio L. Epidemiology of pediatric alopecia areata. Pediatr Dermatol. 2025;42 suppl 1(suppl 1):12-23.

- Karampinis E, Toli O, Georgopoulou KE, et al. Exploring pediatric dermatology in skin of color: focus on dermoscopy. Life (Basel). 2024;14:1604.

- King BA, Senna MM, Ohyama M, et al. Defining severity in alopecia areata: current perspectives and a multidimensional framework. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022;12:825-834.

- Toussi A, Barton VR, Le ST, et al. Psychosocial and psychiatric comorbidities and health-related quality of life in alopecia areata: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:162-175.

- Kalil L, Welch D, Heath CR, et al. Systemic therapies for pediatric alopecia areata. Pediatr Dermatol. 2025;42 suppl 1:36-42.

- King BA, Craiglow BG. Janus kinase inhibitors for alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:S29-S32.

- Klein EJ, Taiwò D, Kakpovbia E, et al. Disparities in Janus kinase inhibitor access for alopecia areata: a retrospective analysis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2024;10:E155.

- McKenzie PL, Maltenfort M, Bruckner AL, et al. Evaluation of the prevalence and incidence of pediatric alopecia areata using electronic health record data. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:547-551. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.0351

- Kara T, Topkarcı Z. Interactions between posttraumatic stress disorder and alopecia areata in child with trauma exposure: two case reports. Int J Trichology. 2018;10:131-134. doi:10.4103/ijt.ijt_2_18

- Sy N, Mastacouris N, Strunk A, et al. Overall and racial and ethnic subgroup prevalences of alopecia areata, alopecia totalis, and alopecia universalis. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:419-423.

- Lee H, Jung SJ, Patel AB, et al. Racial characteristics of alopecia areata in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1064-1070.

- Feaster B, McMichael AJ. Epidemiology of alopecia areata in Black patients: a retrospective chart review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:1121-1123.

- Lee HH, Gwillim E, Patel KR, et al. Epidemiology of alopecia areata, ophiasis, totalis, and universalis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:675-682.

- Mostaghimi A, Gao W, Ray M, et al. Trends in prevalence and incidence of alopecia areata, alopecia totalis, and alopecia universalis among adults and children in a US employer-sponsored insured population. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:411-418.

- Adhanom R, Ansbro B, Castelo-Soccio L. Epidemiology of pediatric alopecia areata. Pediatr Dermatol. 2025;42 suppl 1(suppl 1):12-23.

- Karampinis E, Toli O, Georgopoulou KE, et al. Exploring pediatric dermatology in skin of color: focus on dermoscopy. Life (Basel). 2024;14:1604.

- King BA, Senna MM, Ohyama M, et al. Defining severity in alopecia areata: current perspectives and a multidimensional framework. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022;12:825-834.

- Toussi A, Barton VR, Le ST, et al. Psychosocial and psychiatric comorbidities and health-related quality of life in alopecia areata: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:162-175.

- Kalil L, Welch D, Heath CR, et al. Systemic therapies for pediatric alopecia areata. Pediatr Dermatol. 2025;42 suppl 1:36-42.

- King BA, Craiglow BG. Janus kinase inhibitors for alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:S29-S32.

- Klein EJ, Taiwò D, Kakpovbia E, et al. Disparities in Janus kinase inhibitor access for alopecia areata: a retrospective analysis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2024;10:E155.

- McKenzie PL, Maltenfort M, Bruckner AL, et al. Evaluation of the prevalence and incidence of pediatric alopecia areata using electronic health record data. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:547-551. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.0351

Consider Cultural Practices and Barriers to Care When Treating Alopecia Areata

Consider Cultural Practices and Barriers to Care When Treating Alopecia Areata

A Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Incidence Surveillance Report Among DoD Beneficiaries During the COVID-19 Pandemic

A Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Incidence Surveillance Report Among DoD Beneficiaries During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), or lupus, is a rare autoimmune disease estimated to occur in about 5.1 cases per 100,000 person-years in the United States in 2018.1 The disease predominantly affects females, with an incidence of 8.7 cases per 100,000 person-years vs 1.2 cases per 100,000 person-years in males, and is most common in patients aged 15 to 44 years.1,2

Lupus presents with a constellation of clinical signs and symptoms that evolve, along with hallmark laboratory findings indicative of immune dysregulation and polyclonal B-cell activation. Consequently, a wide array of autoantibodies may be produced, although the combination of epitope specificity can vary from patient to patient.3 Nevertheless, > 98% of individuals diagnosed with lupus produce antinuclear antibodies (ANA), making ANA positivity a near-universal serologic feature at the time of diagnosis.

The pathogenesis of lupus is complex. Research from the past 5 decades supports the role of certain viral infections—such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and cytomegalovirus—as potential triggers.4 These viruses are thought to initiate disease through mechanisms including activation of interferon pathways, exposure of cryptic intracellular antigens, molecular mimicry, and epitope spreading. Subsequent clonal expansion and autoantibody production occur to varying degrees, influenced by viral load and host susceptibility factors.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, it became evident that SARS-CoV-2 exerts profound effects on immune regulation, influencing infection outcomes through mechanisms such as hyperactivation of innate immunity, especially in the lungs, leading to acute respiratory distress syndrome. Additionally, SARS-CoV-2 has been associated with polyclonal B-cell activation and the generation of autoantibodies. This association gained attention after Bastard et al identified anti–type I interferon antibodies in patients with severe COVID-19, predominantly among males with a genetic predisposition. These autoantibodies were shown to impair antiviral defenses and contribute to life-threatening pneumonia.5

Subsequent studies demonstrated the production of a wide spectrum of functional autoantibodies, including ANA, in patients with COVID-19.6,7 These findings were attributed to the acute expansion of autoreactive clones among naïve-derived immunoglobulin G1 antibody-secreting cells during the early stages of infection, with the degree of expansion correlating with disease severity.8,9 Although longitudinal data up to 15 months postinfection suggest this serologic abnormality resolves in more than two-thirds of patients, the number of individuals infected globally has raised serious public health concerns regarding the potential long-term sequelae, including the onset of lupus or other autoimmune diseases in COVID-19 survivors.6-9 A limited number of case reports describing the onset of lupus following SARS-CoV-2 infection support this hypothesis.10

This surveillance analysis investigates lupus incidence among patients within the Military Health System (MHS), encompassing all TRICARE beneficiaries, from January 2018 to December 2022. The objective of this analysis was to examine lupus incidence trends throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, stratified by sex, age, and active-duty status.

Methods

The MHS provides health care services to about 9.5 million US Department of Defense (DoD) beneficiaries. Outpatient health records and laboratory results for individuals receiving care at military treatment facilities (MTFs) between January 1, 2018, and December 31, 2022, were obtained from the Comprehensive Ambulatory/ Professional Encounter Record and MHS GENESIS. For beneficiaries receiving care in the private sector, data were sourced from the TRICARE Encounter Data—Non-Institutional database.

Laboratory test results, including ANA testing, were available only for individuals receiving care at MTFs. These laboratory data were extracted from the Composite Health Care System Chemistry database and MHS GENESIS laboratory systems for the same time frame. Inpatient data were not included in this analysis. Data from 2017 were used solely as a look-back (or washout) period to identify and exclude prevalent lupus cases diagnosed before 2018 and were not included in the final results.

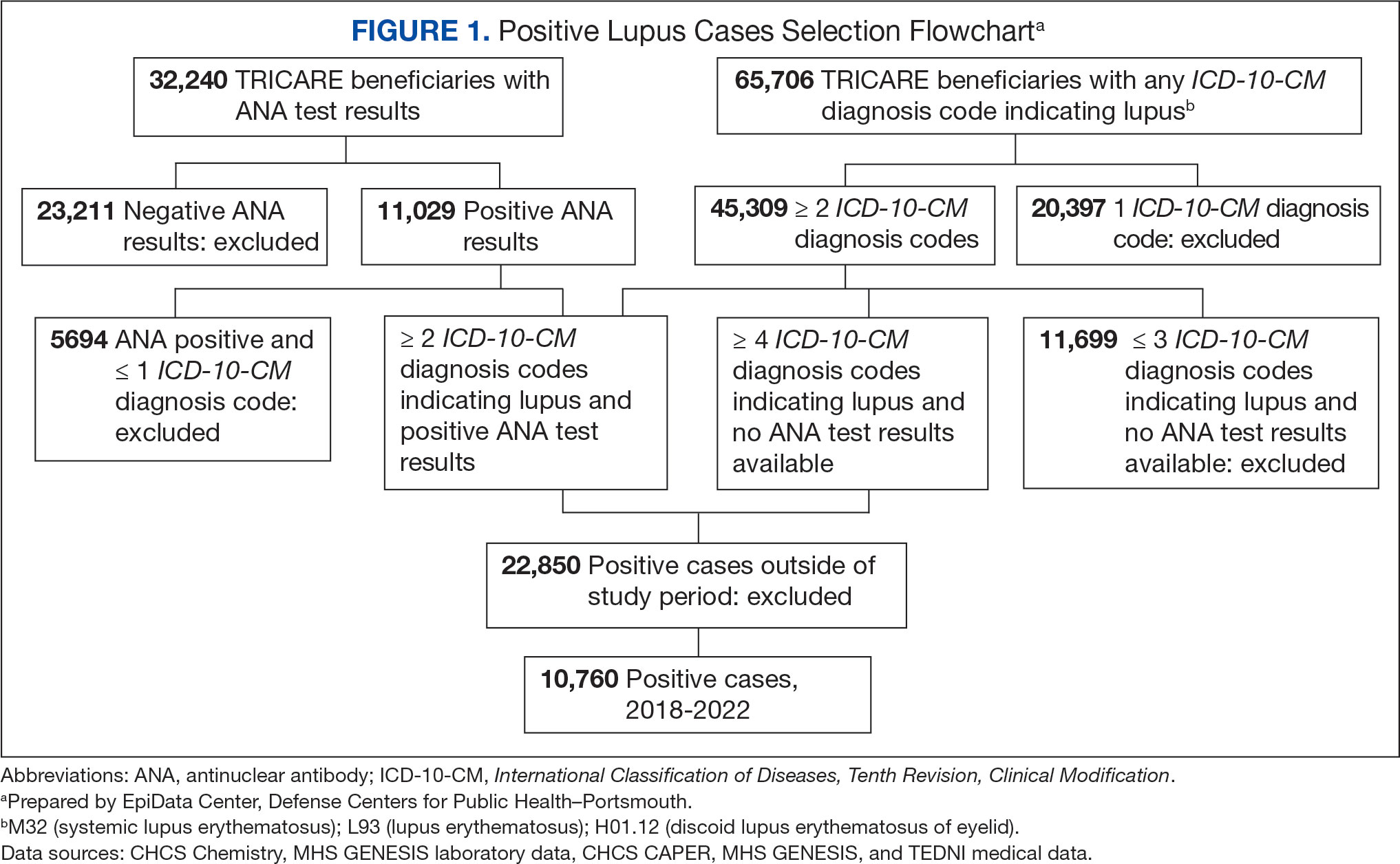

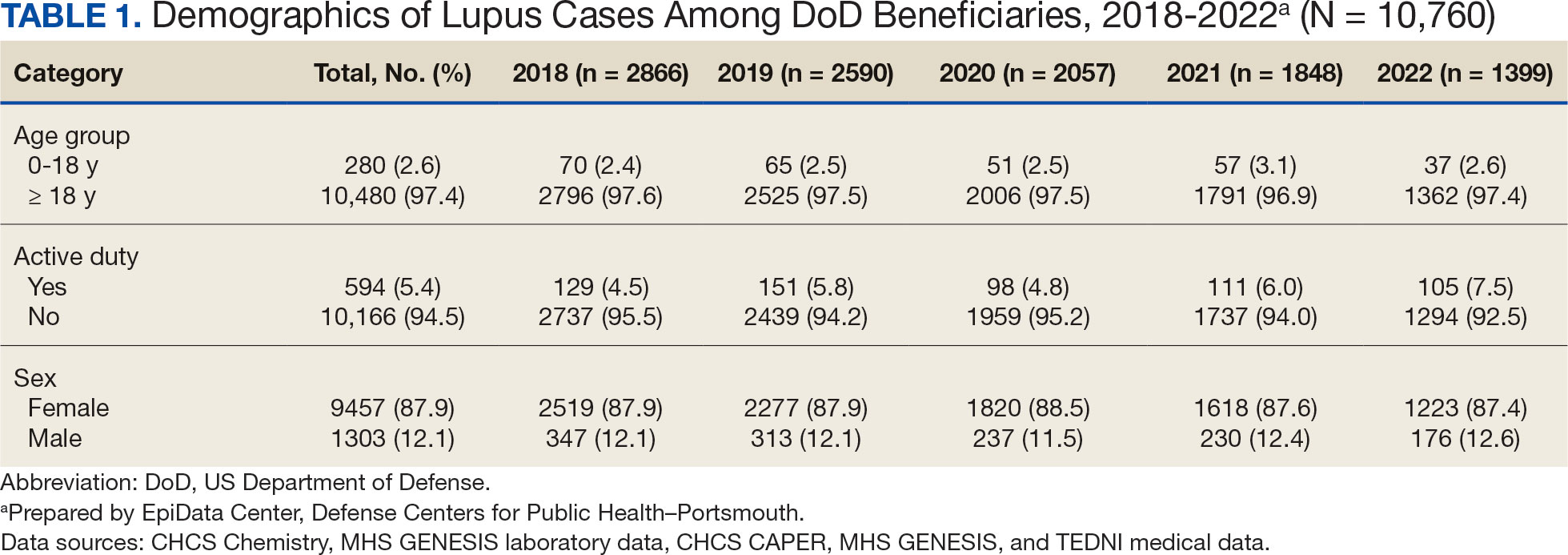

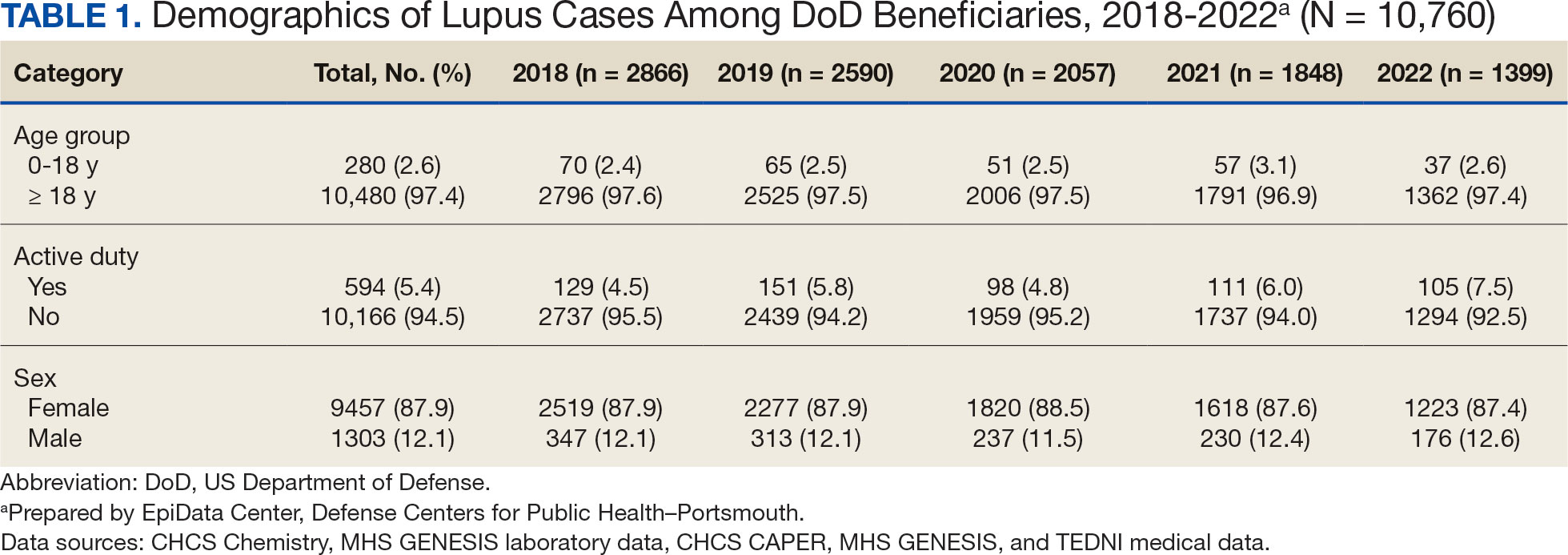

Lupus cases were identified by the presence of a positive ANA test and appropriate International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes. A positive ANA result was defined as either a qualitative result marked positive or a titer ≥ 1:80. The ICD-10-CM codes considered indicative of lupus included variations of M32, L93, or H01.12.

M32, L93, or H01.12. For cases with a positive ANA test, a lupus diagnosis required the presence of ≥ 2 lupus related ICD-10-CM codes. In the absence of ANA test results, a stricter criterion was applied: ≥ 4 lupus ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes recorded on separate days were required for inclusion.

Beneficiaries were excluded if they had a negative ANA result, only 1 lupus ICD- 10-CM diagnosis code, 1 positive ANA with only 1 corresponding ICD-10-CM code, or if their diagnosis occurred outside the defined study period. Patients and members of the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting, or dissemination of this study.

Results

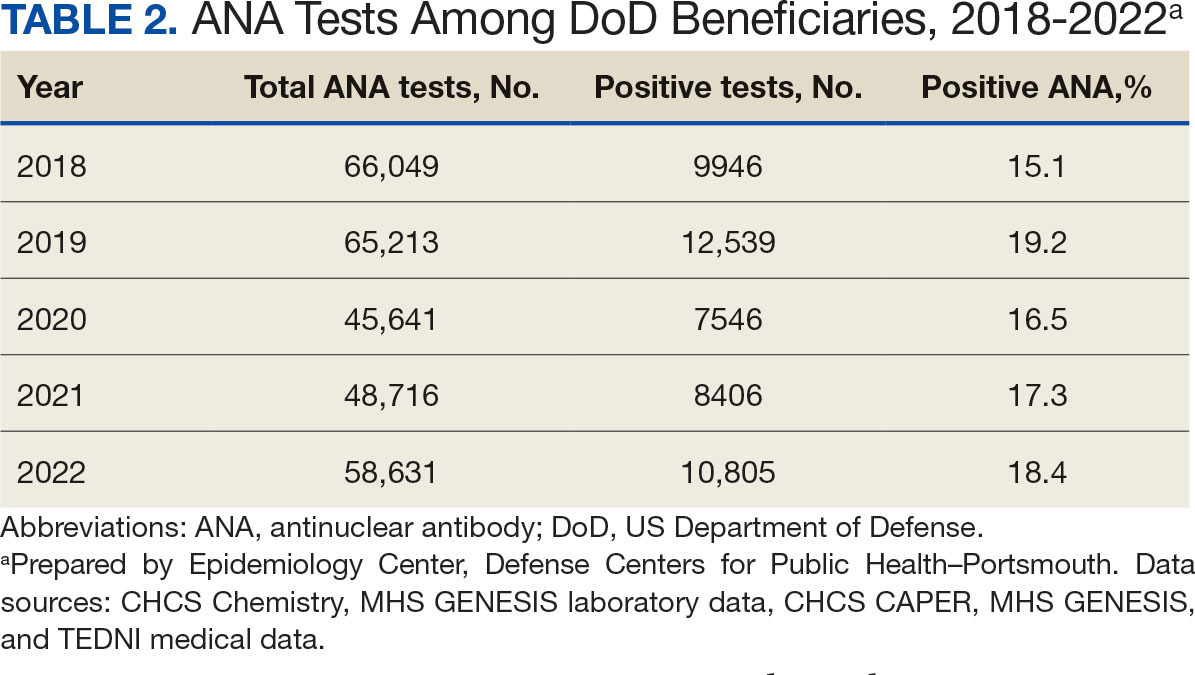

Between January 1, 2017, and December 31, 2022, 99,946 TRICARE beneficiaries had some indication of lupus testing or diagnosis in their health records (Figure 1). Of these beneficiaries, 5335 had a positive ANA result and ≥ 2 ICD-10-CM lupus diagnosis codes. An additional 28,275 beneficiaries had ≥ 4 ICD-10-CM lupus diagnosis codes but no ANA test results. From these groups, the final sample included 10,760 beneficiaries who met the incident case definitions for SLE during the study period (2018 through 2022).

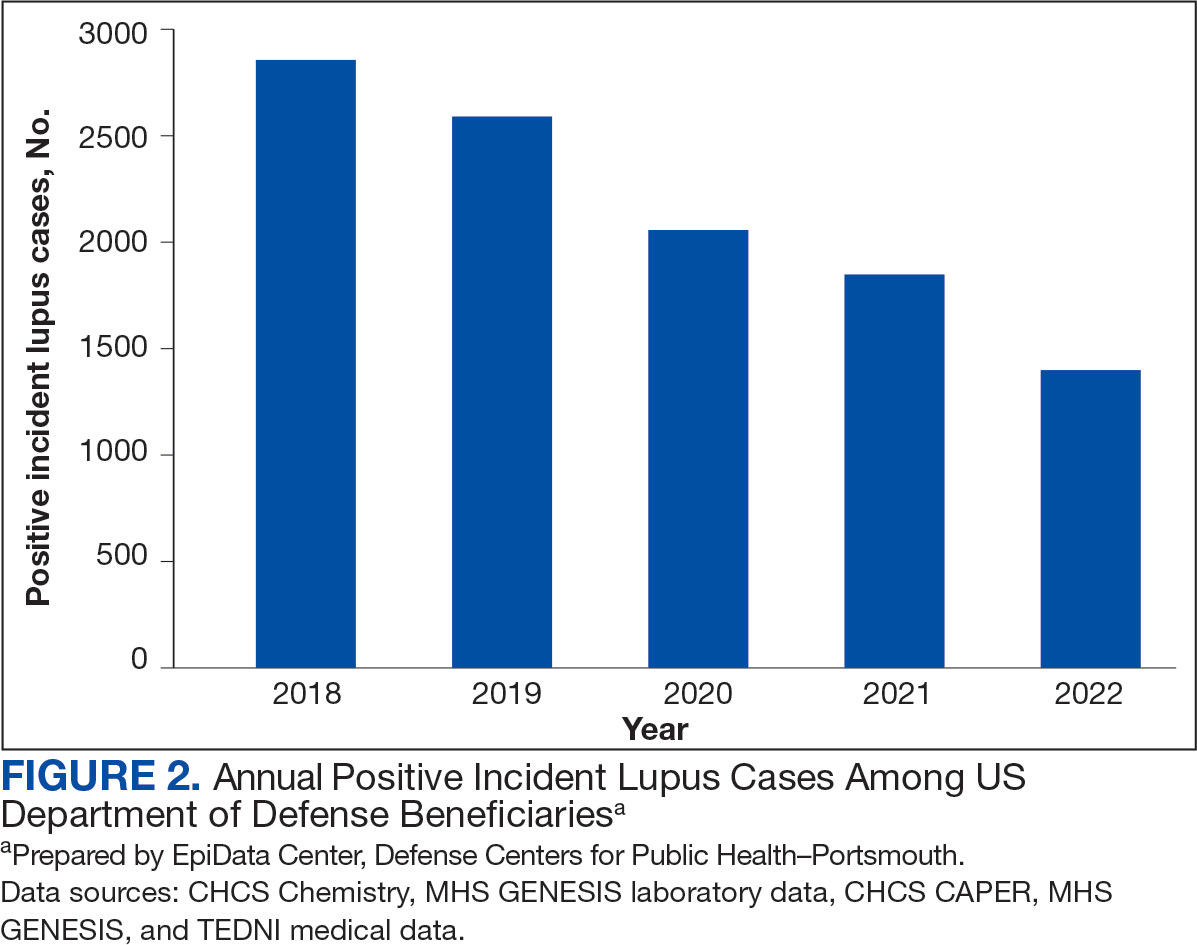

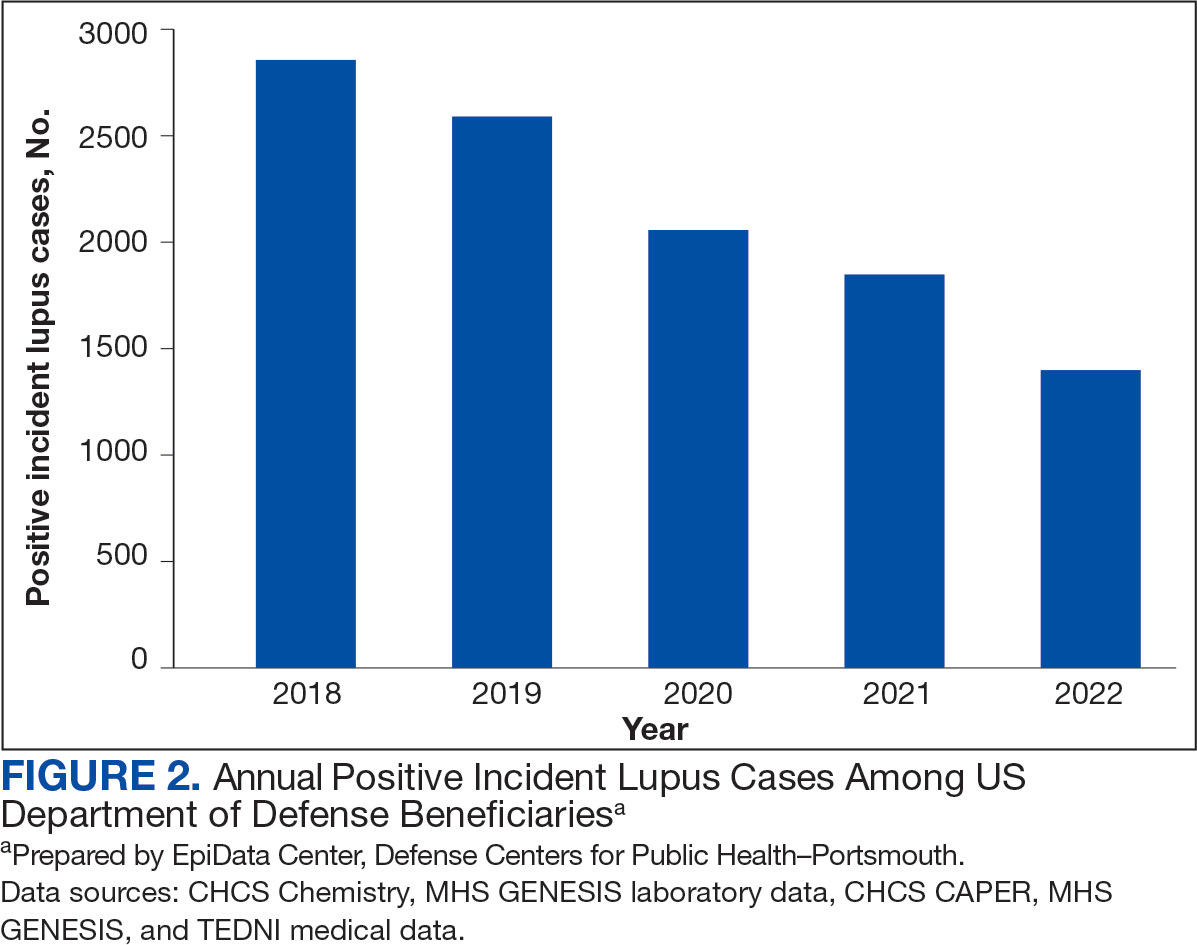

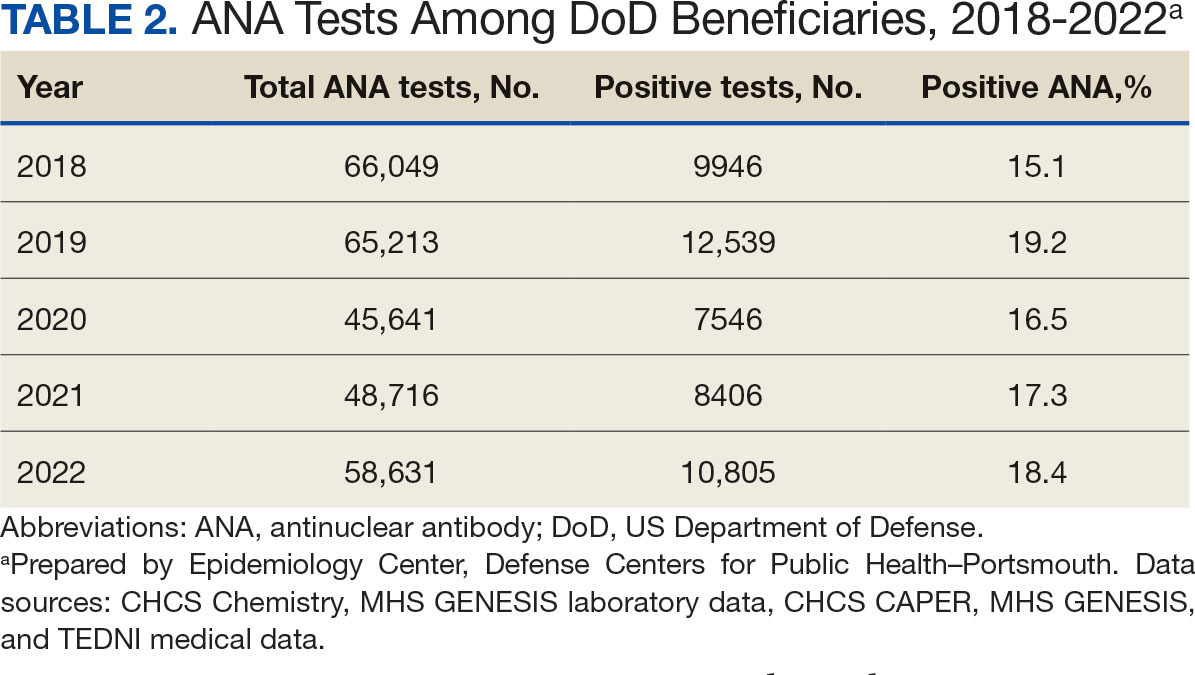

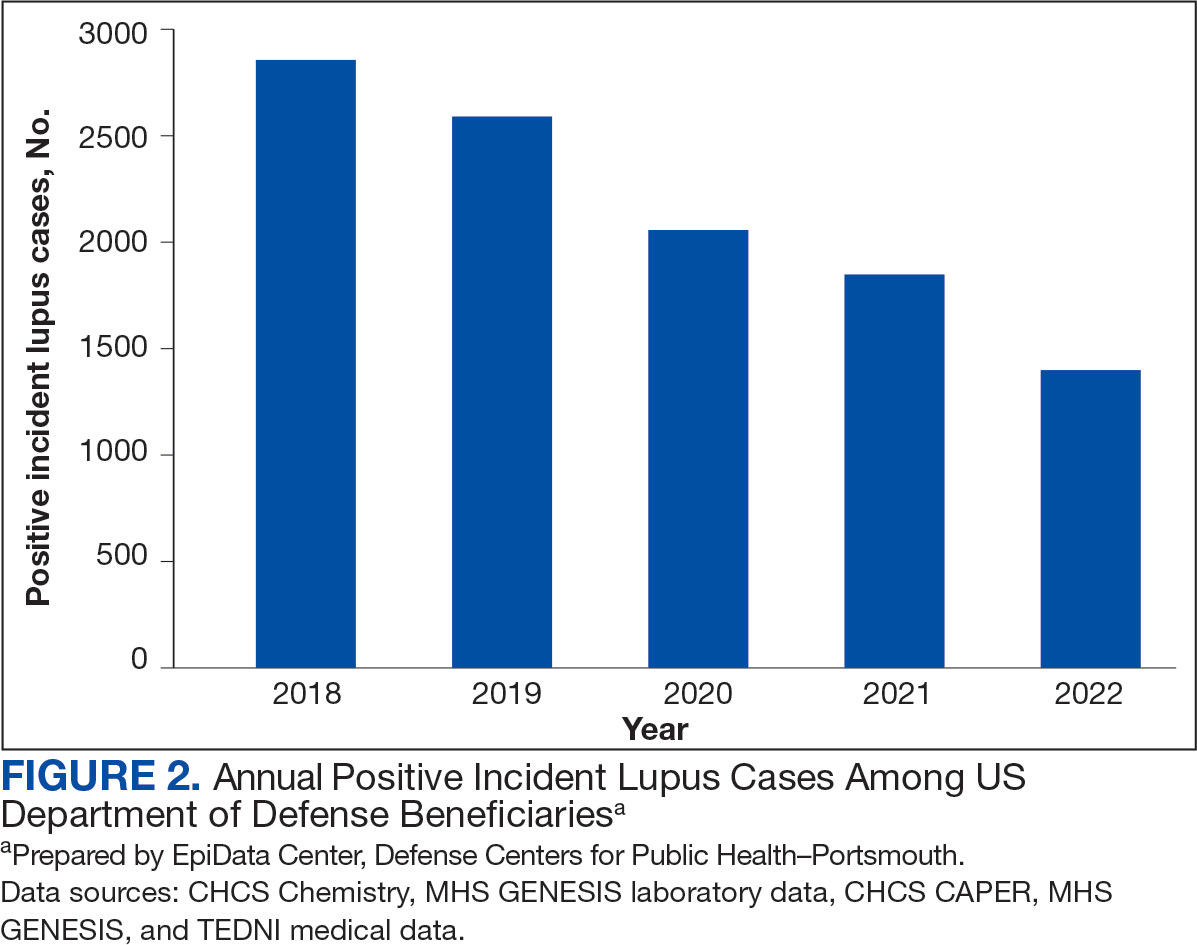

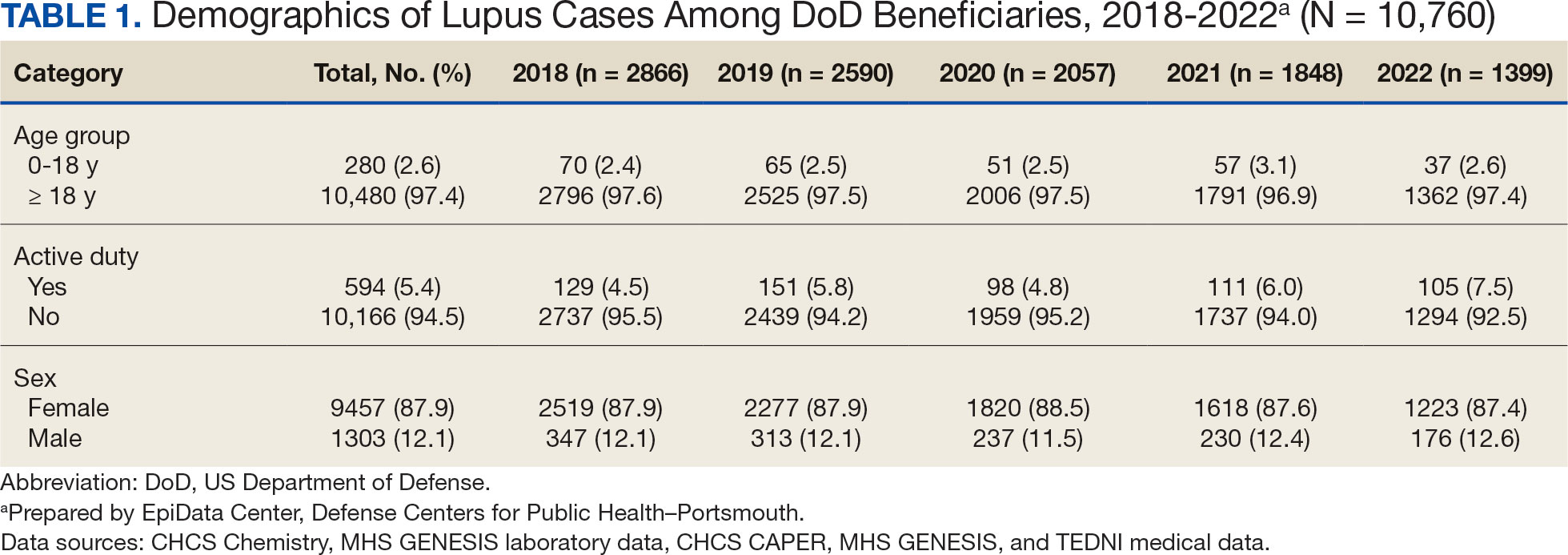

Most cases (85.1%, n = 9157) were diagnosed through TRICARE claims, while 1205 (11.2%) were diagnosed within the MHS. Another 398 (3.7%) had documentation of care both within and outside the MHS. Incident SLE cases declined by an average of 16% annually during the study period (Figure 2). This trend amounted to an overall reduction of 48.2%, from 2866 cases in 2018 to 1399 cases in 2022. This decline occurred despite total medical encounters among DoD beneficiaries remaining relatively stable during the pandemic years, with only a 3.5% change between 2018 and 2022.

The disease was more prevalent among female beneficiaries, with a female to- male ratio of 7:1 (Table 1). Among women, the number of new cases declined from 2519 in 2018 to 1223 in 2022, while the number of cases among men remained consistently < 350 annually. Similar trends were observed across other strata. Incident SLE cases were more common among nonactive-duty beneficiaries than active-duty service members, with a ratio of 18:1. New cases among active-duty members remained < 155 per year. Age-stratified data revealed that SLE was diagnosed predominantly in individuals aged ≥ 18 years, with a ratio of 37:1 compared with individuals aged < 18 years. Among children, the number of new cases remained < 75 per year throughout the study period.

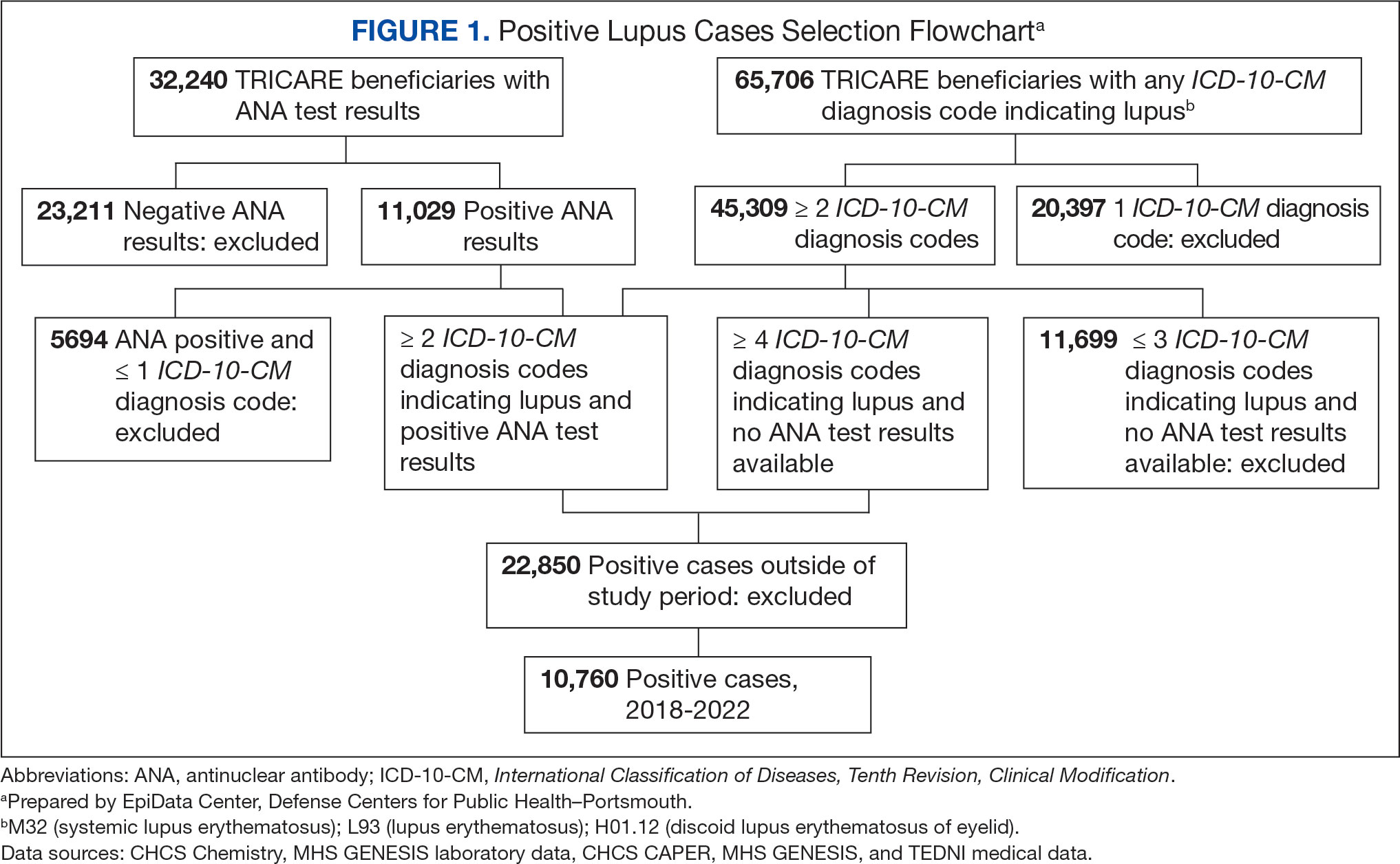

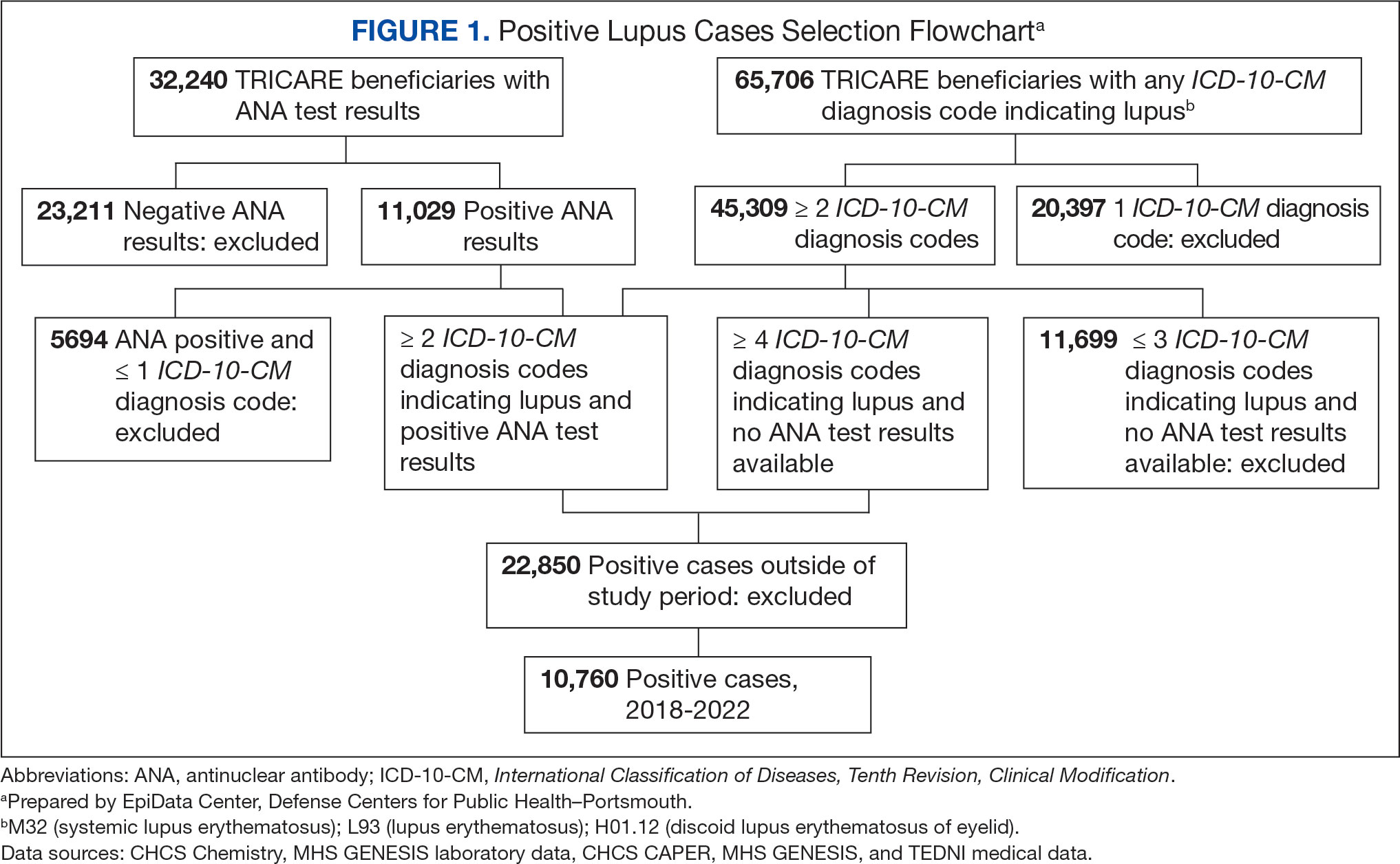

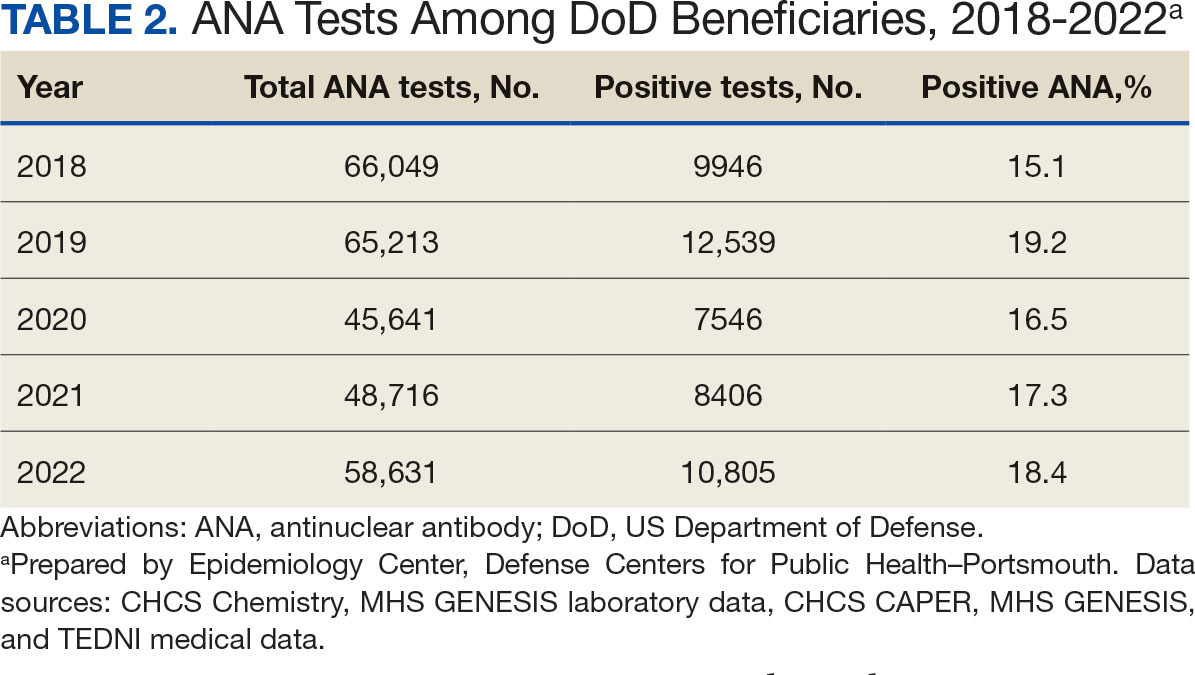

A mean 56,850 ANA tests were conducted annually in centralized laboratories using standardized protocols (Table 2). The mean ANA positivity rate was 17.3%, which remained relatively stable from 2018 through 2022.

Discussion

This study examined the annual incidence of newly diagnosed SLE cases among all TRICARE beneficiaries from January 1, 2018, through December 31, 2022, covering both before and during the peak years of the COVID-19 pandemic. This analysis revealed a steady decline in SLE cases during this period. The reliability of these findings is reinforced by the comprehensiveness of the MHS, one of the largest US health care delivery systems, which maintains near-complete medical data capture for about 9.5 million DoD TRICARE beneficiaries across domestic and international settings.

SLE is a rare autoimmune disorder that presents a diagnostic challenge due to its wide range of nonspecific symptoms, many of which resemble other conditions. To reduce the likelihood of false-positive results and ensure diagnostic accuracy, this study adopted a stringent case definition. Incident cases were identified by the presence of ANA testing in conjunction with lupus-specific ICD-10-CM codes and required ≥ 4 lupus related diagnostic entries. This criterion was necessary due to the absence of ANA test results in data from private sector care settings. Our case definition aligns with established literature. For example, a Vanderbilt University chart review study demonstrated that combining ANA positivity with ≥ 4 lupus related ICD-10-CM codes achieves a positive predictive value of 100%, albeit with a sensitivity of 45%.11 Other studies similarly affirm the diagnostic validity of using recurrent ICD-10-CM codes to improve specificity in identifying lupus cases.12,13

The primary objective of this study was to examine the temporal trend in newly diagnosed lupus cases, rather than derive precise incidence rates. Although the TRICARE system includes about 9.5 million beneficiaries, this number represents a dynamic population with continual inflow and outflow. Accurate incidence rate calculation would require access to detailed denominator data, which were not readily available. In comparison with our findings, a study limited to active-duty service members reported fewer lupus cases. This discrepancy likely reflects differences in case definitions—specifically, the absence of laboratory data, the restricted range of diagnostic codes, and the requirement that diagnoses be rendered by specialists.14 Despite these differences, demographic patterns were consistent, with higher incidence observed in females and individuals aged ≥ 20 years.

A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) study of lupus incidence in the general population also reported lower case counts.1 However, the CDC estimates were based on 5 state-level registries, which rely on clinician-reported cases and therefore may underestimate true disease burden. Moreover, the DoD beneficiary population differs markedly from the general population: it includes a large cohort of retirees, ensuring an older demographic; all members have comprehensive health care access; and active-duty personnel are subject to pre-enlistment medical screening. Taken together, these factors suggest this study may offer a more complete and systematically captured profile of lupus incidence.

We observed a marked decline of newly diagnosed SLE cases during the study period, which coincided with the widespread circulation of COVID-19. This decrease is unlikely to be attributable to reduced access to care during the pandemic. The MHS operates under a single-payer model, and the total number of patient encounters remained relatively stable throughout the pandemic.

To our knowledge, this is the only study to monitor lupus incidence in a large US population over the 5-year period encompassing before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. To date, only 4 large-scale surveillance studies have addressed similar questions. 14-17 Our findings are consistent with the most recent of these reports: an analysis limited to active-duty members of the US Armed Forces identified 1127 patients with newly diagnosed lupus between 2000 and 2022 and reported stable incidence trends throughout the pandemic.14 The other 3 studies adopted a different approach, comparing the emergence of autoimmune diseases, including lupus, between individuals with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection and those without. Each of these trials concluded that COVID-19 increases the risk of various autoimmune conditions, although the findings specific to lupus were inconsistent.15-17

Chang et al reported a significant increase in new lupus diagnoses (n = 2,926,016), with an adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) of 2.99 (95% CI, 2.68-3.34), spanning all ages and both sexes. The highest incidence was observed in individuals of Asian descent.15 Using German routine health care data from 2020, Tesch et al identified a heightened risk of autoimmune diseases, including lupus, among patients with a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection (n = 641,407; 9.4% children, 57.3% female, 6.4% hospitalized), compared with matched infection-naïve controls (n = 1,560,357).16 Both studies excluded vaccinated individuals.

These 2 studies diverged in their assessment of the relationship between COVID-19 severity and subsequent autoimmune risk. Chang et al found a higher incidence among nonhospitalized ambulatory patients, while Tesch et al reported that increased risk was associated with patients requiring intensive care unit admission.15,16

In contrast, based on a cohort of 4,197,188 individuals, Peng et al found no significant difference in lupus incidence among patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection (aHR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.79-1.39).17 Notably, within the infected group, the incidence of SLE was significantly lower among vaccinated individuals compared with the unvaccinated group (aHR, 0.29; 95% CI, 0.18-0.47). Similar protective associations were observed for other antibody-mediated autoimmune disorders, including pemphigoid, Graves’ disease, and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome.

Limitations

Due to fundamental differences in study design, we were unable to directly reconcile our findings with those reported in the literature. This study lacked access to reliable documentation of COVID-19 infection status, primarily due to the widespread use of home testing among TRICARE beneficiaries. Additionally, the dataset did not include inpatient records and therefore did not permit evaluation of disease severity. Despite these constraints, it is plausible that the overall burden of COVID-19 infection within the study population was lower than that observed in the general US population.

As of December 2022, the DoD had reported about 750,000 confirmed COVID-19 cases among military personnel, civilian employees, dependents, and DoD contractors.18 Given that TRICARE beneficiaries represent about 2.8% of the total US population—and that > 90 million US individuals were infected between 2020 and 2022—the implied infection rate in our cohort appears to be about one-third of what might be expected.19 This discrepancy may be due to higher adherence to mitigation measures, such as social distancing and mask usage, among DoD-affiliated populations. COVID-19 vaccination was mandated for all active-duty service members, who constitute 5.4% of the study population. The remaining TRICARE beneficiaries also had access to guaranteed health care and vaccination coverage, likely contributing to high overall vaccination rates.

Because > 80% of the study population was composed of individuals from diverse civilian backgrounds, we expect the distribution of infection severity within the DoD beneficiary population to approximate that of the general US population.

Future Directions

The findings of this study offer circumstantial yet real-time evidence of the complexity underlying immune dysregulation at the intersection of host susceptibility and environmental exposures. The stability in ANA positivity rates during the study period mitigates concerns regarding undiagnosed subclinical lupus and may suggest that, overall, immune homeostasis was preserved among DoD beneficiaries.

It is noteworthy that during the COVID-19 pandemic, the incidence of several common infections—such as influenza and EBV—declined markedly, likely as a result of widespread social distancing and other public health interventions.20 Mitigation strategies implemented within the military may have conferred protection not only against COVID-19 but also against other community-acquired pathogens.

In light of these observations, we hypothesize that for COVID-19 to act as a trigger for SLE, a prolonged or repeated disruption of immune equilibrium may be required—potentially mediated by recurrent infections or sustained inflammatory states. The association between viral infections and autoimmunity is well established. Immune dysregulation leading to autoantibody production has been observed not only in the context of SARS-CoV-2 but also following infections with EBV, cytomegalovirus, enteroviruses, hepatitis B and C viruses, HIV, and parvovirus B19.21

This dysregulation is often transient, accompanied by compensatory immune regulatory responses. However, in individuals subjected to successive or overlapping infections, these regulatory mechanisms may become compromised or overwhelmed, due to emergent patterns of immune interference of varying severity. In such cases, a transient immune perturbation may progress into a bona fide autoimmune disease, contingent upon individual risk factors such as genetic predisposition, preexisting immune memory, and regenerative capacity.21

Therefore, we believe the significance of this study is 2-fold. First, lupus is known to develop gradually and may require 3 to 5 years to clinically manifest after the initial break in immunological tolerance.3 Continued public health surveillance represents a more pragmatic strategy than retrospective cohort construction, especially as histories of COVID-19 infection become increasingly complete and definitive. Our findings provide a valuable baseline reference point for future longitudinal studies.

The interpretation of surveillance outcomes—whether indicating an upward trend, a stable baseline, or a downward trend—offers distinct analytical value. Within this study population, we observed neither an upward trajectory that might suggest a direct causal link, nor a flat trend that would imply absence of association between COVID-19 and lupus pathogenesis. Instead, the observation of a downward trend invites consideration of nonlinear or protective influences. From this perspective, we recommend that future investigations adopt a holistic framework when assessing environmental contributions to immune dysregulation—particularly when evaluating the long-term immunopathological consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on lupus and related autoimmune conditions.

Conclusions

This study identified a declining trend in incident lupus cases during the COVID-19 pandemic among the DoD beneficiary population. Further investigation is warranted to elucidate the underlying factors contributing to this decline. Conducting longitudinal epidemiologic studies and applying multivariable regression analyses will be essential to determine whether incidence rates revert to prepandemic baselines and how these trends may be influenced by evolving environmental factors within the general population.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), or lupus, is a rare autoimmune disease estimated to occur in about 5.1 cases per 100,000 person-years in the United States in 2018.1 The disease predominantly affects females, with an incidence of 8.7 cases per 100,000 person-years vs 1.2 cases per 100,000 person-years in males, and is most common in patients aged 15 to 44 years.1,2

Lupus presents with a constellation of clinical signs and symptoms that evolve, along with hallmark laboratory findings indicative of immune dysregulation and polyclonal B-cell activation. Consequently, a wide array of autoantibodies may be produced, although the combination of epitope specificity can vary from patient to patient.3 Nevertheless, > 98% of individuals diagnosed with lupus produce antinuclear antibodies (ANA), making ANA positivity a near-universal serologic feature at the time of diagnosis.

The pathogenesis of lupus is complex. Research from the past 5 decades supports the role of certain viral infections—such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and cytomegalovirus—as potential triggers.4 These viruses are thought to initiate disease through mechanisms including activation of interferon pathways, exposure of cryptic intracellular antigens, molecular mimicry, and epitope spreading. Subsequent clonal expansion and autoantibody production occur to varying degrees, influenced by viral load and host susceptibility factors.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, it became evident that SARS-CoV-2 exerts profound effects on immune regulation, influencing infection outcomes through mechanisms such as hyperactivation of innate immunity, especially in the lungs, leading to acute respiratory distress syndrome. Additionally, SARS-CoV-2 has been associated with polyclonal B-cell activation and the generation of autoantibodies. This association gained attention after Bastard et al identified anti–type I interferon antibodies in patients with severe COVID-19, predominantly among males with a genetic predisposition. These autoantibodies were shown to impair antiviral defenses and contribute to life-threatening pneumonia.5

Subsequent studies demonstrated the production of a wide spectrum of functional autoantibodies, including ANA, in patients with COVID-19.6,7 These findings were attributed to the acute expansion of autoreactive clones among naïve-derived immunoglobulin G1 antibody-secreting cells during the early stages of infection, with the degree of expansion correlating with disease severity.8,9 Although longitudinal data up to 15 months postinfection suggest this serologic abnormality resolves in more than two-thirds of patients, the number of individuals infected globally has raised serious public health concerns regarding the potential long-term sequelae, including the onset of lupus or other autoimmune diseases in COVID-19 survivors.6-9 A limited number of case reports describing the onset of lupus following SARS-CoV-2 infection support this hypothesis.10

This surveillance analysis investigates lupus incidence among patients within the Military Health System (MHS), encompassing all TRICARE beneficiaries, from January 2018 to December 2022. The objective of this analysis was to examine lupus incidence trends throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, stratified by sex, age, and active-duty status.

Methods

The MHS provides health care services to about 9.5 million US Department of Defense (DoD) beneficiaries. Outpatient health records and laboratory results for individuals receiving care at military treatment facilities (MTFs) between January 1, 2018, and December 31, 2022, were obtained from the Comprehensive Ambulatory/ Professional Encounter Record and MHS GENESIS. For beneficiaries receiving care in the private sector, data were sourced from the TRICARE Encounter Data—Non-Institutional database.

Laboratory test results, including ANA testing, were available only for individuals receiving care at MTFs. These laboratory data were extracted from the Composite Health Care System Chemistry database and MHS GENESIS laboratory systems for the same time frame. Inpatient data were not included in this analysis. Data from 2017 were used solely as a look-back (or washout) period to identify and exclude prevalent lupus cases diagnosed before 2018 and were not included in the final results.

Lupus cases were identified by the presence of a positive ANA test and appropriate International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes. A positive ANA result was defined as either a qualitative result marked positive or a titer ≥ 1:80. The ICD-10-CM codes considered indicative of lupus included variations of M32, L93, or H01.12.

M32, L93, or H01.12. For cases with a positive ANA test, a lupus diagnosis required the presence of ≥ 2 lupus related ICD-10-CM codes. In the absence of ANA test results, a stricter criterion was applied: ≥ 4 lupus ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes recorded on separate days were required for inclusion.

Beneficiaries were excluded if they had a negative ANA result, only 1 lupus ICD- 10-CM diagnosis code, 1 positive ANA with only 1 corresponding ICD-10-CM code, or if their diagnosis occurred outside the defined study period. Patients and members of the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting, or dissemination of this study.

Results

Between January 1, 2017, and December 31, 2022, 99,946 TRICARE beneficiaries had some indication of lupus testing or diagnosis in their health records (Figure 1). Of these beneficiaries, 5335 had a positive ANA result and ≥ 2 ICD-10-CM lupus diagnosis codes. An additional 28,275 beneficiaries had ≥ 4 ICD-10-CM lupus diagnosis codes but no ANA test results. From these groups, the final sample included 10,760 beneficiaries who met the incident case definitions for SLE during the study period (2018 through 2022).