User login

For MD-IQ use only

White Atrophic Plaques on the Thighs

White Atrophic Plaques on the Thighs

THE DIAGNOSIS: Lichen Sclerosus

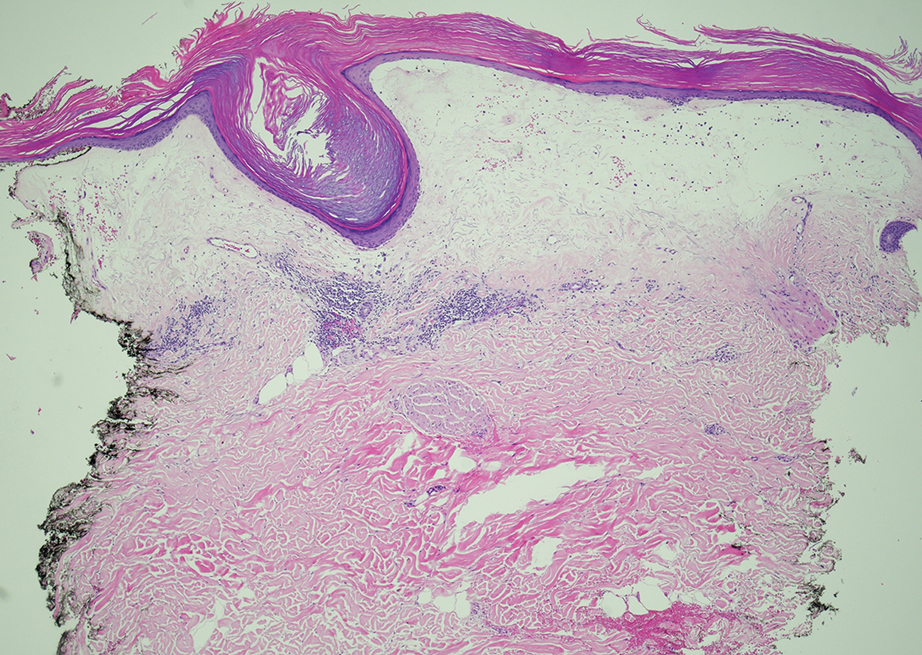

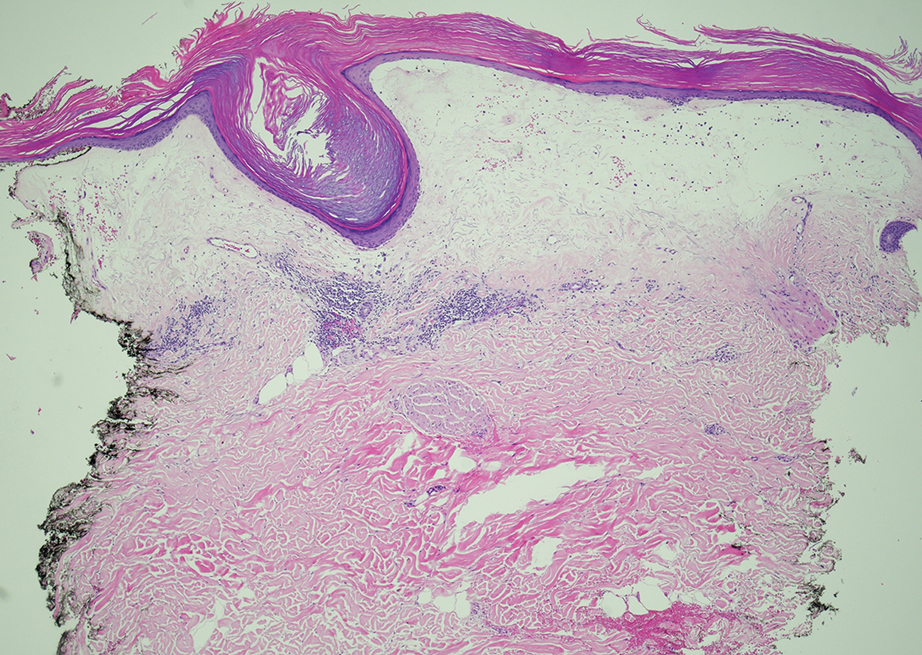

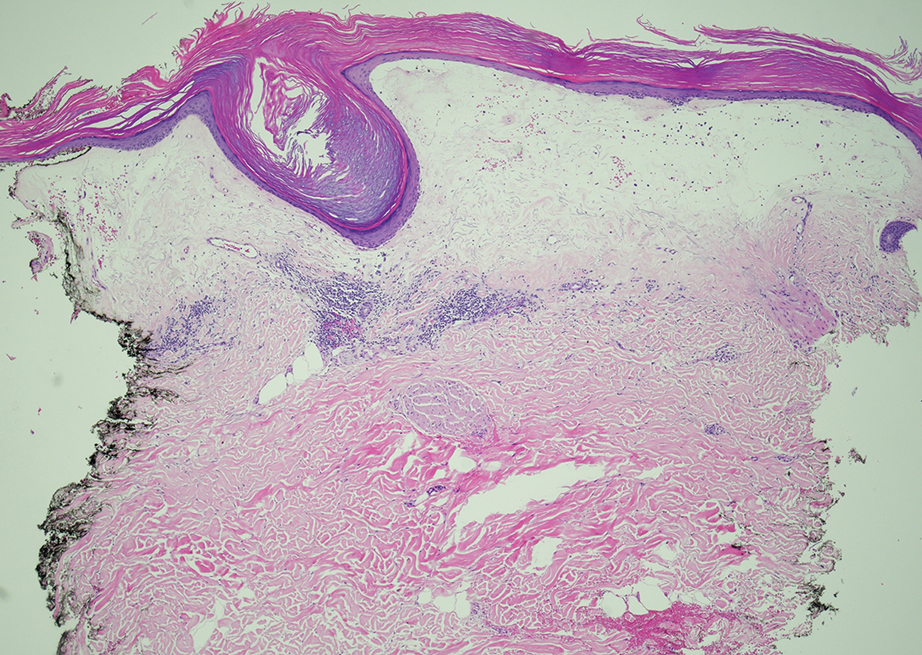

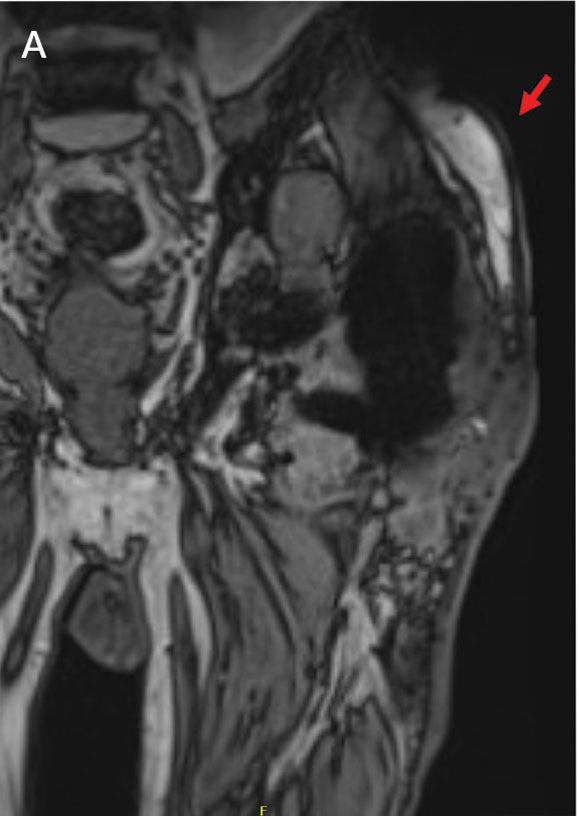

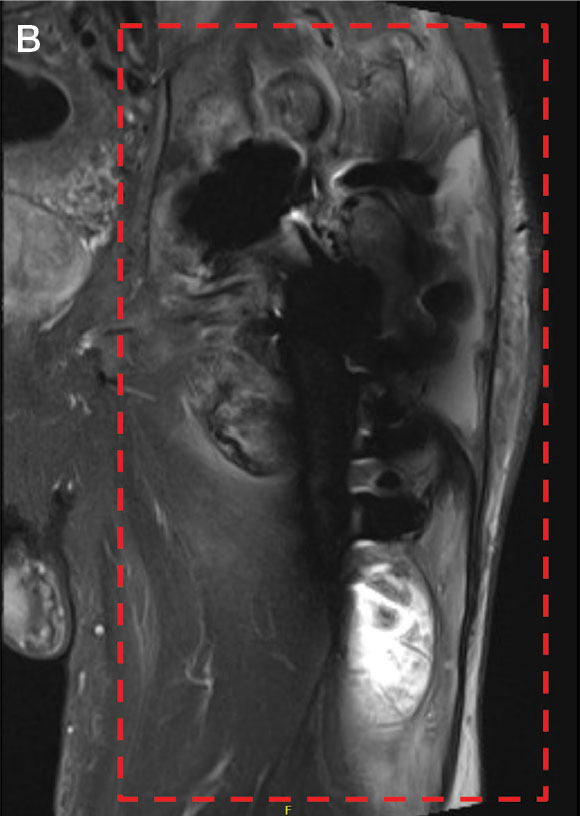

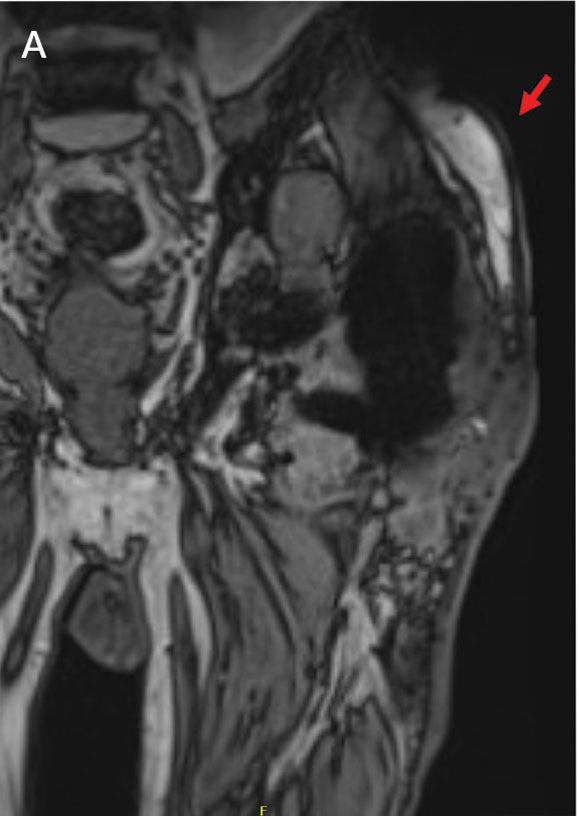

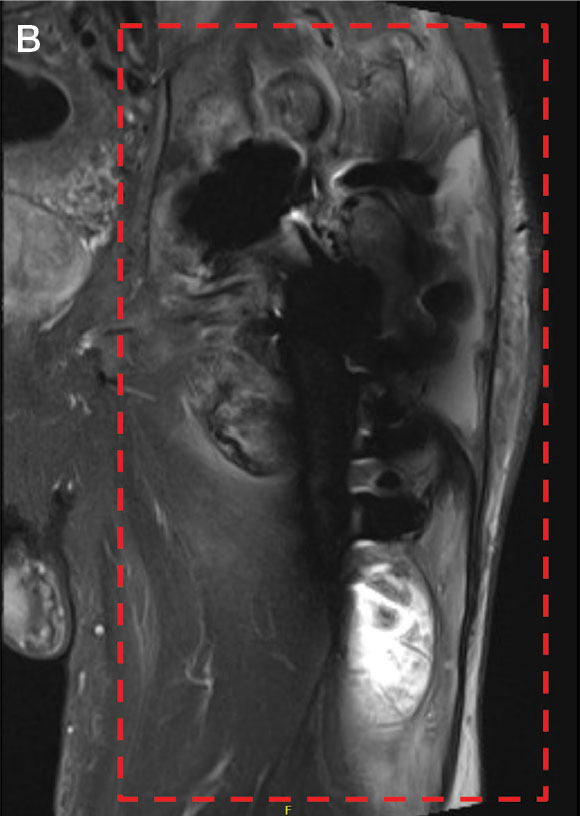

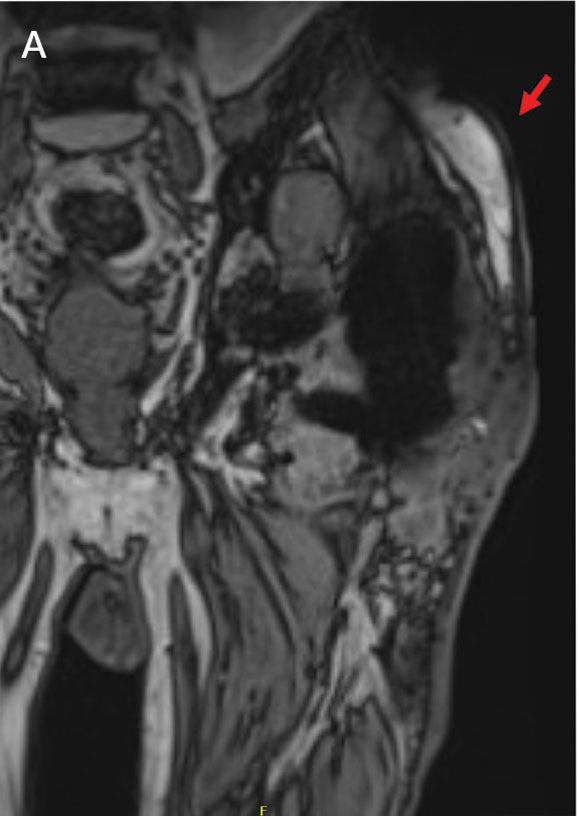

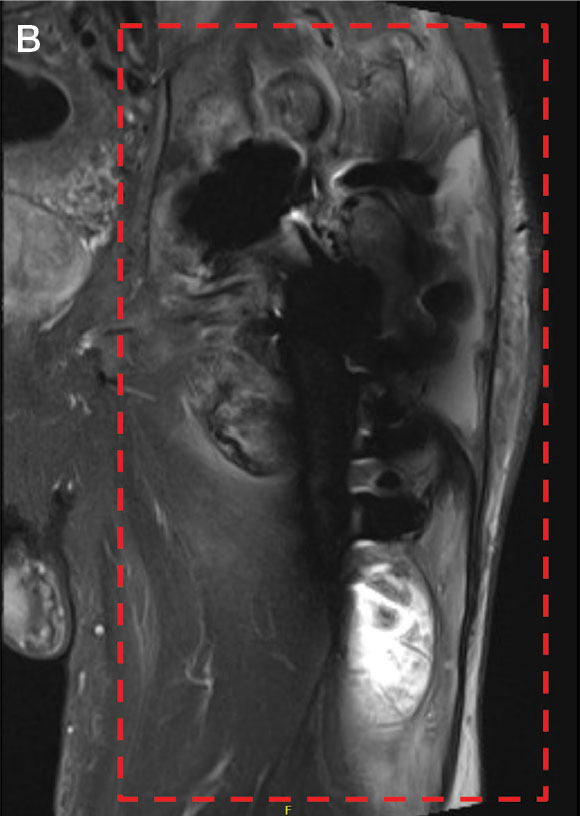

Given the clinical appearance of white atrophic plaques with characteristic wrinkling of the skin, a diagnosis of lichen sclerosus was strongly suspected. At the initial office visit, the patient was prescribed clobetasol 0.05% ointment twice daily for 6 weeks. Histopathology revealed hyperkeratosis, follicular plugging, papillary dermal pallor, and adjacent lymphocytic inflammation, confirming the clinical diagnosis of lichen sclerosus (Figure). The patient then was lost to follow-up.

Lichen sclerosus is a chronic benign dermatologic condition of unknown etiology that is characterized by epidermal atrophy and inflammation and is common in postmenopausal women. It features pale, ivory-colored lesions with partially atrophic skin and a wrinkled cigarette paper appearance.1 The differential for lichen sclerosus is broad, and definitive diagnosis is made via biopsy to rule out potential malignancy and other inflammatory skin diseases.1 Lichen sclerosus is an immune-mediated disorder driven by type 1 T helper cells and regulated by miR-155. There has been an association with extracellular matrix protein 1, a glycoprotein that is found in the dermal-epidermal basement membrane zone, which provides structural integrity to the skin. Autoantibodies against extracellular matrix protein 1 and other antigens in the basement membrane generally are found in anogenital lichen sclerosus; however, their precise roles in the pathogenesis of lichen sclerosus remains unclear.1

The differential diagnoses for lichen sclerosus include psoriasis, tinea corporis, lichen simplex chronicus, and atopic dermatitis. Psoriasis typically manifests as pink plaques with silver scales on the elbows, knees, and scalp in adult patients.2 Our patient’s white plaques may have suggested psoriasis, but the partially atrophic skin with a wrinkled cigarette paper appearance was not compatible with that diagnosis.

Tinea corporis, a superficial fungal infection of the skin, manifests as circular or ovoid lesions with raised erythematous scaly borders, often with central clearing resembling a ring, that can occur anywhere on the body other than the feet, groin, face, scalp, or beard area.3 The fact that our patient previously had tried topical antifungal medications with no relief and that the skin lesions were atrophic rather than ring shaped made the diagnosis of tinea corporis unlikely.

Lichen simplex chronicus is a chronic condition caused by friction or scratching that is characterized by dry, patchy, scaly, and thickened areas of the skin. Typically affecting the head, arms, neck, scalp, and genital region, lichen simplex chronicus manifests with violaceous or hyperpigmented lesions.4 The nonpruritic atrophic plaques on the inner thighs and the presence of white patches on the vaginal area were not indicative of lichen simplex chronicus in our patient.

Atopic dermatitis manifests as pruritic erythematous scaly papules and plaques with secondary excoriation and possible lichenification. In adults, atopic dermatitis commonly appears on flexural surfaces.2 Atopic dermatitis does not manifest with atrophy and skin wrinkling as seen in our patient.

In the management of lichen sclerosus, the standard treatment is potent topical corticosteroids. Alternatively, topical calcineurin inhibitors can be employed; however, due to the unknown nature of the condition’s underlying cause, targeted treatment is challenging. Our case underscores how lichen sclerosus can be misdiagnosed, highlighting the need for more frequent reporting in the literature to enhance early recognition and reduce delays in patient treatment.

- De Luca DA, Papara C, Vorobyev A, et al. Lichen sclerosus: the 2023 update. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1106318. doi:10.3389 /fmed.2023.1106318

- Chovatiya R, Silverberg JI. Pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis: implications for management in children. Children (Basel). 2019;6:108. doi:10.3390/children6100108

- Trayes KP, Savage K, Studdiford JS. Annular lesions: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2018;98:283-291.

- Ju T, Vander Does A, Mohsin N, et al. Lichen simplex chronicus itch: an update. Acta Derm Venereol. 2022;102:adv00796. doi:10.2340 /actadv.v102.4367

THE DIAGNOSIS: Lichen Sclerosus

Given the clinical appearance of white atrophic plaques with characteristic wrinkling of the skin, a diagnosis of lichen sclerosus was strongly suspected. At the initial office visit, the patient was prescribed clobetasol 0.05% ointment twice daily for 6 weeks. Histopathology revealed hyperkeratosis, follicular plugging, papillary dermal pallor, and adjacent lymphocytic inflammation, confirming the clinical diagnosis of lichen sclerosus (Figure). The patient then was lost to follow-up.

Lichen sclerosus is a chronic benign dermatologic condition of unknown etiology that is characterized by epidermal atrophy and inflammation and is common in postmenopausal women. It features pale, ivory-colored lesions with partially atrophic skin and a wrinkled cigarette paper appearance.1 The differential for lichen sclerosus is broad, and definitive diagnosis is made via biopsy to rule out potential malignancy and other inflammatory skin diseases.1 Lichen sclerosus is an immune-mediated disorder driven by type 1 T helper cells and regulated by miR-155. There has been an association with extracellular matrix protein 1, a glycoprotein that is found in the dermal-epidermal basement membrane zone, which provides structural integrity to the skin. Autoantibodies against extracellular matrix protein 1 and other antigens in the basement membrane generally are found in anogenital lichen sclerosus; however, their precise roles in the pathogenesis of lichen sclerosus remains unclear.1

The differential diagnoses for lichen sclerosus include psoriasis, tinea corporis, lichen simplex chronicus, and atopic dermatitis. Psoriasis typically manifests as pink plaques with silver scales on the elbows, knees, and scalp in adult patients.2 Our patient’s white plaques may have suggested psoriasis, but the partially atrophic skin with a wrinkled cigarette paper appearance was not compatible with that diagnosis.

Tinea corporis, a superficial fungal infection of the skin, manifests as circular or ovoid lesions with raised erythematous scaly borders, often with central clearing resembling a ring, that can occur anywhere on the body other than the feet, groin, face, scalp, or beard area.3 The fact that our patient previously had tried topical antifungal medications with no relief and that the skin lesions were atrophic rather than ring shaped made the diagnosis of tinea corporis unlikely.

Lichen simplex chronicus is a chronic condition caused by friction or scratching that is characterized by dry, patchy, scaly, and thickened areas of the skin. Typically affecting the head, arms, neck, scalp, and genital region, lichen simplex chronicus manifests with violaceous or hyperpigmented lesions.4 The nonpruritic atrophic plaques on the inner thighs and the presence of white patches on the vaginal area were not indicative of lichen simplex chronicus in our patient.

Atopic dermatitis manifests as pruritic erythematous scaly papules and plaques with secondary excoriation and possible lichenification. In adults, atopic dermatitis commonly appears on flexural surfaces.2 Atopic dermatitis does not manifest with atrophy and skin wrinkling as seen in our patient.

In the management of lichen sclerosus, the standard treatment is potent topical corticosteroids. Alternatively, topical calcineurin inhibitors can be employed; however, due to the unknown nature of the condition’s underlying cause, targeted treatment is challenging. Our case underscores how lichen sclerosus can be misdiagnosed, highlighting the need for more frequent reporting in the literature to enhance early recognition and reduce delays in patient treatment.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Lichen Sclerosus

Given the clinical appearance of white atrophic plaques with characteristic wrinkling of the skin, a diagnosis of lichen sclerosus was strongly suspected. At the initial office visit, the patient was prescribed clobetasol 0.05% ointment twice daily for 6 weeks. Histopathology revealed hyperkeratosis, follicular plugging, papillary dermal pallor, and adjacent lymphocytic inflammation, confirming the clinical diagnosis of lichen sclerosus (Figure). The patient then was lost to follow-up.

Lichen sclerosus is a chronic benign dermatologic condition of unknown etiology that is characterized by epidermal atrophy and inflammation and is common in postmenopausal women. It features pale, ivory-colored lesions with partially atrophic skin and a wrinkled cigarette paper appearance.1 The differential for lichen sclerosus is broad, and definitive diagnosis is made via biopsy to rule out potential malignancy and other inflammatory skin diseases.1 Lichen sclerosus is an immune-mediated disorder driven by type 1 T helper cells and regulated by miR-155. There has been an association with extracellular matrix protein 1, a glycoprotein that is found in the dermal-epidermal basement membrane zone, which provides structural integrity to the skin. Autoantibodies against extracellular matrix protein 1 and other antigens in the basement membrane generally are found in anogenital lichen sclerosus; however, their precise roles in the pathogenesis of lichen sclerosus remains unclear.1

The differential diagnoses for lichen sclerosus include psoriasis, tinea corporis, lichen simplex chronicus, and atopic dermatitis. Psoriasis typically manifests as pink plaques with silver scales on the elbows, knees, and scalp in adult patients.2 Our patient’s white plaques may have suggested psoriasis, but the partially atrophic skin with a wrinkled cigarette paper appearance was not compatible with that diagnosis.

Tinea corporis, a superficial fungal infection of the skin, manifests as circular or ovoid lesions with raised erythematous scaly borders, often with central clearing resembling a ring, that can occur anywhere on the body other than the feet, groin, face, scalp, or beard area.3 The fact that our patient previously had tried topical antifungal medications with no relief and that the skin lesions were atrophic rather than ring shaped made the diagnosis of tinea corporis unlikely.

Lichen simplex chronicus is a chronic condition caused by friction or scratching that is characterized by dry, patchy, scaly, and thickened areas of the skin. Typically affecting the head, arms, neck, scalp, and genital region, lichen simplex chronicus manifests with violaceous or hyperpigmented lesions.4 The nonpruritic atrophic plaques on the inner thighs and the presence of white patches on the vaginal area were not indicative of lichen simplex chronicus in our patient.

Atopic dermatitis manifests as pruritic erythematous scaly papules and plaques with secondary excoriation and possible lichenification. In adults, atopic dermatitis commonly appears on flexural surfaces.2 Atopic dermatitis does not manifest with atrophy and skin wrinkling as seen in our patient.

In the management of lichen sclerosus, the standard treatment is potent topical corticosteroids. Alternatively, topical calcineurin inhibitors can be employed; however, due to the unknown nature of the condition’s underlying cause, targeted treatment is challenging. Our case underscores how lichen sclerosus can be misdiagnosed, highlighting the need for more frequent reporting in the literature to enhance early recognition and reduce delays in patient treatment.

- De Luca DA, Papara C, Vorobyev A, et al. Lichen sclerosus: the 2023 update. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1106318. doi:10.3389 /fmed.2023.1106318

- Chovatiya R, Silverberg JI. Pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis: implications for management in children. Children (Basel). 2019;6:108. doi:10.3390/children6100108

- Trayes KP, Savage K, Studdiford JS. Annular lesions: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2018;98:283-291.

- Ju T, Vander Does A, Mohsin N, et al. Lichen simplex chronicus itch: an update. Acta Derm Venereol. 2022;102:adv00796. doi:10.2340 /actadv.v102.4367

- De Luca DA, Papara C, Vorobyev A, et al. Lichen sclerosus: the 2023 update. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1106318. doi:10.3389 /fmed.2023.1106318

- Chovatiya R, Silverberg JI. Pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis: implications for management in children. Children (Basel). 2019;6:108. doi:10.3390/children6100108

- Trayes KP, Savage K, Studdiford JS. Annular lesions: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2018;98:283-291.

- Ju T, Vander Does A, Mohsin N, et al. Lichen simplex chronicus itch: an update. Acta Derm Venereol. 2022;102:adv00796. doi:10.2340 /actadv.v102.4367

White Atrophic Plaques on the Thighs

White Atrophic Plaques on the Thighs

A 71-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of intense pruritus of the vaginal region and a nonpruritic rash on the inner thighs of 7 months’ duration. Physical examination revealed white atrophic plaques with scaling and a wrinkled appearance on the inner thighs. White atrophic patches also were noted on the vulva. The patient reported that she had tried over-the-counter antifungals with no improvement. A punch biopsy was performed.

Gastroenterology Knows No Country

The United States boasts one of the premier health care systems for medical education in the world. Indeed, institutions such as Johns Hopkins, Harvard, and the Mayo Clinic have storied reputations and are recognized names the world over. The United States also stands as a country of remarkable discovery in medicine with an abundance of enormously talented and productive medical scientists. This reputation draws physicians from every corner of the world who dream of studying medicine in our country.

Unfortunately, many US medical institutions, particularly the most prestigious medical centers, lean heavily toward preferential acceptance of US medical school graduates as an indicator of the highest-quality trainees. This historical bias is being further compounded by our current government’s pejorative view of immigrants in general. Will this affect the pool of tomorrow’s stars who will change the course of American medicine?

A glance at the list of recent AGA Presidents may yield some insight; over the past 10 years, three of our presidents trained internationally at universities in Malta, Libya, and Germany. This is a small snapshot of the multitude of international graduates in gastroenterology and hepatology who have served as division chiefs, AGA award winners, and journal editors, all now US citizens. This is not to mention the influence of varied insights and talents native to international study and culture that enhance our practice of medicine and biomedical research.

We live in time when “immigrant” has been assigned a negative and almost subhuman connotation, and diversity has become something to be demonized rather than celebrated. Yet, intuitively, should a top US medical graduate be any more intelligent or driven than a top graduate from the United Kingdom, India, China, or Syria? As American medical physicians, we place the utmost value on our traditions and high standards. We boast an unmatched depth of medical talent spread across our GI divisions and practices and take pride in the way we teach medicine, like no other nation. American medicine benefits from their talent and they inspire us to remember and care for diseases in our field that affect the world’s population, not just ours.

Over 100 years ago, Dr. William Mayo stated “American practice is too broad to be national. It had the scientific spirit, and science knows no country.” Dr. Mayo also said, “Democracy is safe only so long as culture is in the ascendancy.” These lessons apply more than ever today.

David Katzka, MD

Associate Editor

The United States boasts one of the premier health care systems for medical education in the world. Indeed, institutions such as Johns Hopkins, Harvard, and the Mayo Clinic have storied reputations and are recognized names the world over. The United States also stands as a country of remarkable discovery in medicine with an abundance of enormously talented and productive medical scientists. This reputation draws physicians from every corner of the world who dream of studying medicine in our country.

Unfortunately, many US medical institutions, particularly the most prestigious medical centers, lean heavily toward preferential acceptance of US medical school graduates as an indicator of the highest-quality trainees. This historical bias is being further compounded by our current government’s pejorative view of immigrants in general. Will this affect the pool of tomorrow’s stars who will change the course of American medicine?

A glance at the list of recent AGA Presidents may yield some insight; over the past 10 years, three of our presidents trained internationally at universities in Malta, Libya, and Germany. This is a small snapshot of the multitude of international graduates in gastroenterology and hepatology who have served as division chiefs, AGA award winners, and journal editors, all now US citizens. This is not to mention the influence of varied insights and talents native to international study and culture that enhance our practice of medicine and biomedical research.

We live in time when “immigrant” has been assigned a negative and almost subhuman connotation, and diversity has become something to be demonized rather than celebrated. Yet, intuitively, should a top US medical graduate be any more intelligent or driven than a top graduate from the United Kingdom, India, China, or Syria? As American medical physicians, we place the utmost value on our traditions and high standards. We boast an unmatched depth of medical talent spread across our GI divisions and practices and take pride in the way we teach medicine, like no other nation. American medicine benefits from their talent and they inspire us to remember and care for diseases in our field that affect the world’s population, not just ours.

Over 100 years ago, Dr. William Mayo stated “American practice is too broad to be national. It had the scientific spirit, and science knows no country.” Dr. Mayo also said, “Democracy is safe only so long as culture is in the ascendancy.” These lessons apply more than ever today.

David Katzka, MD

Associate Editor

The United States boasts one of the premier health care systems for medical education in the world. Indeed, institutions such as Johns Hopkins, Harvard, and the Mayo Clinic have storied reputations and are recognized names the world over. The United States also stands as a country of remarkable discovery in medicine with an abundance of enormously talented and productive medical scientists. This reputation draws physicians from every corner of the world who dream of studying medicine in our country.

Unfortunately, many US medical institutions, particularly the most prestigious medical centers, lean heavily toward preferential acceptance of US medical school graduates as an indicator of the highest-quality trainees. This historical bias is being further compounded by our current government’s pejorative view of immigrants in general. Will this affect the pool of tomorrow’s stars who will change the course of American medicine?

A glance at the list of recent AGA Presidents may yield some insight; over the past 10 years, three of our presidents trained internationally at universities in Malta, Libya, and Germany. This is a small snapshot of the multitude of international graduates in gastroenterology and hepatology who have served as division chiefs, AGA award winners, and journal editors, all now US citizens. This is not to mention the influence of varied insights and talents native to international study and culture that enhance our practice of medicine and biomedical research.

We live in time when “immigrant” has been assigned a negative and almost subhuman connotation, and diversity has become something to be demonized rather than celebrated. Yet, intuitively, should a top US medical graduate be any more intelligent or driven than a top graduate from the United Kingdom, India, China, or Syria? As American medical physicians, we place the utmost value on our traditions and high standards. We boast an unmatched depth of medical talent spread across our GI divisions and practices and take pride in the way we teach medicine, like no other nation. American medicine benefits from their talent and they inspire us to remember and care for diseases in our field that affect the world’s population, not just ours.

Over 100 years ago, Dr. William Mayo stated “American practice is too broad to be national. It had the scientific spirit, and science knows no country.” Dr. Mayo also said, “Democracy is safe only so long as culture is in the ascendancy.” These lessons apply more than ever today.

David Katzka, MD

Associate Editor

How Doctors Use Travel to Heal Themselves

Whatever’s ailing you, a vacation might just be the cure. Yes, getting away can improve your health, according to research published in in 2023. It might help combat symptoms of aging, suggested a 2024 study in Journal of Travel Research. But it could also have even more powerful psychological and physical benefits, transforming your life before you pack a bag and long after you return home.

This news organization spoke with two healthcare professionals who believe in the healing power of travel. They shared which personal “diagnoses” they have successfully treated with faraway places and how this therapy might work for you.

Stacey Funt, MD, NBC-HWC, a radiologist at Northwell Health in Long Island, New York, started the boutique wellness adventure travel company, LH Adventure Travel, in 2023. Funt curates and leads small groups to destinations like Peru, Guatemala, Morocco, and Italy. Each tour incorporates tenets of lifestyle medicine, including healthy eating, movement, stress management, and community building.

Kiya Thompson, RN, a surgical trauma nurse for 20 years, was similarly inspired to share her passion for travel. She is now a certified family travel coach who helps parents plan meaningful trips through her company, LuckyBucky, LLC.

Dx: Self-Esteem Deficiency / Rx: Vivaldi in Venice

In June 2015, Thompson found herself at an all-time low. As a nurse, she felt confident that she was “built for the adrenaline rush and could take on anything.” But outside the trauma center, Thompson felt inadequate, her self-esteem eroded by years of abusive relationships. “The daily hardships of my personal life, combined with the mental fortitude it took to endure the demands of caring for the sickest of the sick, were incredibly weighty,” she recalled.

To escape, Thompson booked her first solo trip: 3 weeks in Italy. But days after she arrived, she felt the need to “escape her escape.” On a bus in Naples, she was pick-pocketed. The man she had been dating before her trip stopped responding to her messages. In her hotel room in Venice, she felt “lost, alone, and helpless.”

One evening, Thompson attended a small orchestral performance of Vivaldi’s “The Four Seasons” in a centuries-old church. The music triggered memories of her Italian grandparents at whose home she’d listened to the same piece.

“A switch flipped, and I changed my whole outlook,” she remembers.

During the concert, she reflected on strangers who had shown her kindness and care. A Canadian man who gave her €50 after her wallet was stolen. A friend-of-a-friend who showed her around Rome. The clerk at her Venice hotel who had offered her a hug.

“In the wake of experiencing the worst of people, I’d experienced so much more of the best of people; strangers who were willing to go above and beyond to help me,” Thompson said.

When Thompson returned home, she brought her new mindset along. “ My ability to problem-solve my way through a solo trip that presented unexpected hardships empowered me,” she explained. “I learned I was much more capable than I’d thought.”

Dx: Wilderness Phobia / Rx: A Safari in Tanzania

On an evening in the mid-1990s, Funt was alone in a tent on a budget camping safari in Tanzania. Animals roared threateningly outside the thin walls. Earlier that day, a vulture had ripped a sandwich out of her hands. Funt was frightened to the core. Worrying that she’d be the next meal for the local wildlife, she started to sob. “This was as raw as I had ever gotten at that point in my life,” she said.

Suddenly, Funt said her brain shifted into problem-solving mode. She made one small decision: To switch to a different Jeep for the next day’s excursion. Having made a seemingly insignificant choice, she felt calmer and no longer like a victim. It brought control. Instead of worrying, she began looking forward to the wildlife she would see.

In the morning, in the new Jeep, she befriended a nurse from Canada. Together, they visited the Maasai Mara tribe and nearby pubs, meeting members of the community.

“It was the most exciting experience of my life,” Funt said. “And it had started with me crying.”

Dx: Parenting-itis / Rx: A Mountain Getaway

As Thompson pointed out, sometimes the destination is secondary to the intension behind a trip. And the quality of the time away matters more than how long you can stay. After becoming parents 4 years ago, Thompson and her husband hadn’t traveled alone together. Like many parents of young children, they were short on time to relax and reconnect as a couple.

So Thompson planned a weekend trip to an isolated cabin in the Massanutten Mountain Range within the George Washington National Forest, about a 2-hour drive from their Washington, DC, area home.

“We put our devices away and focused on being completely present with one another,” said Thompson. The couple took a walk in the woods, where “all we could hear were drops of water from the snowmelt, the crunch of the snow beneath our feet, and the occasional bird looking for food,” she recalled. “There were no cars, no other people. It was quiet, calm, and incredibly peaceful.”

Whether sitting by the fire, soaking in the outdoor hot tub, or playing card games, “our conversation didn’t surround what we’d have for dinner or who would do baths and bedtime with whom,” Thompson said. “We didn’t talk about work, upcoming commitments, or items on our to-do lists.” The getaway was so refreshing, the couple intend to repeat the trip each year.

Dx: Persistent Grief / Rx: Hiking and Hinduism in Nepal

Nearly 3 years ago, Funt experienced a 2-month period where both of her kids left for college and both her father and father-in-law passed away. Besieged by grief, she found herself questioning whether her best years were behind her. She was also grappling with her mortality, because she was then approaching 59, the age at which her own mother had died. So Funt decided to go trekking in Nepal. “I am a traveler — it’s what I do,” she said.

Having the trip to prepare for changed Funt’s whole outlook, she remembers. Throwing herself into the planning helped her transcend her grief. But being in Nepal was even more impactful. She and her husband spent hours trekking through majestic mountain ranges, which “touched their souls.” At a crematorium, they learned about Hindu beliefs on death, which helped them with the grieving process.

The trip “lifted me so high up on so many levels and brought me back to my authentic self,” Funt said. On her flight home from Kathmandu, she decided to start her travel business.

“I needed something else [in addition to radiology] to put my passion, heart, and creativity into, and it would be another way of doing service,” she explained.

Dx: Couch Potato Syndrome / Rx: Planning an Adventure

Like all of us, Funt knows exercise is important for health. But that knowledge alone doesn’t motivate her to move, she admitted. What does get her off the couch is scheduling an active trip — and then training for it. “When I have a goal tied to my values of adventure, connection, and community, fear will set in if I don’t start to move,” she said. It was after booking her Nepal trip (which included an 8-mile, 3000-foot trek) that Funt started getting in shape.

Travel has motivated Funt’s clients in similar ways. Last year, 8 months before one of her Morocco trips, Funt spoke over Zoom with a woman who’d just enrolled. This woman told her she’d signed up in order to commit to her health.

By the time Funt saw her again, on day 1 of the trip, the woman had lost 50 pounds. “It was the greatest transformation,” Funt recalled. “On the trip, she was the first one up the mountain and beamed the whole time. It was beautiful to watch her reclaim her power, body, and life.”

Getting Lost — Finding Inspiration

Since Thompson’s trip to Italy, she has traveled extensively, visiting nearly 25 countries. “Traveling inspired me to continue exploring the world and myself,” she said.

Since leading her first trip to Morocco in 2023, Funt said she’s received more letters of appreciation from her clients than her patients. The results from this type of travel therapy can be dramatic.

After a trip with Funt, one burned-out physician decided that she needed to find a job with a better work-life balance. An empty nester realized the “feeling of belonging and community” on the trip was what had been missing in her “regular” life. After returning home, she began rekindling relationships with old friends.

To many, a vacation is a treat. But, as Funt and Thompson have learned firsthand, it can also be a prescription — for ennui, sadness, loneliness, and all the physical issues that come with them. Sometimes, going far away helps you come home to yourself.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Whatever’s ailing you, a vacation might just be the cure. Yes, getting away can improve your health, according to research published in in 2023. It might help combat symptoms of aging, suggested a 2024 study in Journal of Travel Research. But it could also have even more powerful psychological and physical benefits, transforming your life before you pack a bag and long after you return home.

This news organization spoke with two healthcare professionals who believe in the healing power of travel. They shared which personal “diagnoses” they have successfully treated with faraway places and how this therapy might work for you.

Stacey Funt, MD, NBC-HWC, a radiologist at Northwell Health in Long Island, New York, started the boutique wellness adventure travel company, LH Adventure Travel, in 2023. Funt curates and leads small groups to destinations like Peru, Guatemala, Morocco, and Italy. Each tour incorporates tenets of lifestyle medicine, including healthy eating, movement, stress management, and community building.

Kiya Thompson, RN, a surgical trauma nurse for 20 years, was similarly inspired to share her passion for travel. She is now a certified family travel coach who helps parents plan meaningful trips through her company, LuckyBucky, LLC.

Dx: Self-Esteem Deficiency / Rx: Vivaldi in Venice

In June 2015, Thompson found herself at an all-time low. As a nurse, she felt confident that she was “built for the adrenaline rush and could take on anything.” But outside the trauma center, Thompson felt inadequate, her self-esteem eroded by years of abusive relationships. “The daily hardships of my personal life, combined with the mental fortitude it took to endure the demands of caring for the sickest of the sick, were incredibly weighty,” she recalled.

To escape, Thompson booked her first solo trip: 3 weeks in Italy. But days after she arrived, she felt the need to “escape her escape.” On a bus in Naples, she was pick-pocketed. The man she had been dating before her trip stopped responding to her messages. In her hotel room in Venice, she felt “lost, alone, and helpless.”

One evening, Thompson attended a small orchestral performance of Vivaldi’s “The Four Seasons” in a centuries-old church. The music triggered memories of her Italian grandparents at whose home she’d listened to the same piece.

“A switch flipped, and I changed my whole outlook,” she remembers.

During the concert, she reflected on strangers who had shown her kindness and care. A Canadian man who gave her €50 after her wallet was stolen. A friend-of-a-friend who showed her around Rome. The clerk at her Venice hotel who had offered her a hug.

“In the wake of experiencing the worst of people, I’d experienced so much more of the best of people; strangers who were willing to go above and beyond to help me,” Thompson said.

When Thompson returned home, she brought her new mindset along. “ My ability to problem-solve my way through a solo trip that presented unexpected hardships empowered me,” she explained. “I learned I was much more capable than I’d thought.”

Dx: Wilderness Phobia / Rx: A Safari in Tanzania

On an evening in the mid-1990s, Funt was alone in a tent on a budget camping safari in Tanzania. Animals roared threateningly outside the thin walls. Earlier that day, a vulture had ripped a sandwich out of her hands. Funt was frightened to the core. Worrying that she’d be the next meal for the local wildlife, she started to sob. “This was as raw as I had ever gotten at that point in my life,” she said.

Suddenly, Funt said her brain shifted into problem-solving mode. She made one small decision: To switch to a different Jeep for the next day’s excursion. Having made a seemingly insignificant choice, she felt calmer and no longer like a victim. It brought control. Instead of worrying, she began looking forward to the wildlife she would see.

In the morning, in the new Jeep, she befriended a nurse from Canada. Together, they visited the Maasai Mara tribe and nearby pubs, meeting members of the community.

“It was the most exciting experience of my life,” Funt said. “And it had started with me crying.”

Dx: Parenting-itis / Rx: A Mountain Getaway

As Thompson pointed out, sometimes the destination is secondary to the intension behind a trip. And the quality of the time away matters more than how long you can stay. After becoming parents 4 years ago, Thompson and her husband hadn’t traveled alone together. Like many parents of young children, they were short on time to relax and reconnect as a couple.

So Thompson planned a weekend trip to an isolated cabin in the Massanutten Mountain Range within the George Washington National Forest, about a 2-hour drive from their Washington, DC, area home.

“We put our devices away and focused on being completely present with one another,” said Thompson. The couple took a walk in the woods, where “all we could hear were drops of water from the snowmelt, the crunch of the snow beneath our feet, and the occasional bird looking for food,” she recalled. “There were no cars, no other people. It was quiet, calm, and incredibly peaceful.”

Whether sitting by the fire, soaking in the outdoor hot tub, or playing card games, “our conversation didn’t surround what we’d have for dinner or who would do baths and bedtime with whom,” Thompson said. “We didn’t talk about work, upcoming commitments, or items on our to-do lists.” The getaway was so refreshing, the couple intend to repeat the trip each year.

Dx: Persistent Grief / Rx: Hiking and Hinduism in Nepal

Nearly 3 years ago, Funt experienced a 2-month period where both of her kids left for college and both her father and father-in-law passed away. Besieged by grief, she found herself questioning whether her best years were behind her. She was also grappling with her mortality, because she was then approaching 59, the age at which her own mother had died. So Funt decided to go trekking in Nepal. “I am a traveler — it’s what I do,” she said.

Having the trip to prepare for changed Funt’s whole outlook, she remembers. Throwing herself into the planning helped her transcend her grief. But being in Nepal was even more impactful. She and her husband spent hours trekking through majestic mountain ranges, which “touched their souls.” At a crematorium, they learned about Hindu beliefs on death, which helped them with the grieving process.

The trip “lifted me so high up on so many levels and brought me back to my authentic self,” Funt said. On her flight home from Kathmandu, she decided to start her travel business.

“I needed something else [in addition to radiology] to put my passion, heart, and creativity into, and it would be another way of doing service,” she explained.

Dx: Couch Potato Syndrome / Rx: Planning an Adventure

Like all of us, Funt knows exercise is important for health. But that knowledge alone doesn’t motivate her to move, she admitted. What does get her off the couch is scheduling an active trip — and then training for it. “When I have a goal tied to my values of adventure, connection, and community, fear will set in if I don’t start to move,” she said. It was after booking her Nepal trip (which included an 8-mile, 3000-foot trek) that Funt started getting in shape.

Travel has motivated Funt’s clients in similar ways. Last year, 8 months before one of her Morocco trips, Funt spoke over Zoom with a woman who’d just enrolled. This woman told her she’d signed up in order to commit to her health.

By the time Funt saw her again, on day 1 of the trip, the woman had lost 50 pounds. “It was the greatest transformation,” Funt recalled. “On the trip, she was the first one up the mountain and beamed the whole time. It was beautiful to watch her reclaim her power, body, and life.”

Getting Lost — Finding Inspiration

Since Thompson’s trip to Italy, she has traveled extensively, visiting nearly 25 countries. “Traveling inspired me to continue exploring the world and myself,” she said.

Since leading her first trip to Morocco in 2023, Funt said she’s received more letters of appreciation from her clients than her patients. The results from this type of travel therapy can be dramatic.

After a trip with Funt, one burned-out physician decided that she needed to find a job with a better work-life balance. An empty nester realized the “feeling of belonging and community” on the trip was what had been missing in her “regular” life. After returning home, she began rekindling relationships with old friends.

To many, a vacation is a treat. But, as Funt and Thompson have learned firsthand, it can also be a prescription — for ennui, sadness, loneliness, and all the physical issues that come with them. Sometimes, going far away helps you come home to yourself.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Whatever’s ailing you, a vacation might just be the cure. Yes, getting away can improve your health, according to research published in in 2023. It might help combat symptoms of aging, suggested a 2024 study in Journal of Travel Research. But it could also have even more powerful psychological and physical benefits, transforming your life before you pack a bag and long after you return home.

This news organization spoke with two healthcare professionals who believe in the healing power of travel. They shared which personal “diagnoses” they have successfully treated with faraway places and how this therapy might work for you.

Stacey Funt, MD, NBC-HWC, a radiologist at Northwell Health in Long Island, New York, started the boutique wellness adventure travel company, LH Adventure Travel, in 2023. Funt curates and leads small groups to destinations like Peru, Guatemala, Morocco, and Italy. Each tour incorporates tenets of lifestyle medicine, including healthy eating, movement, stress management, and community building.

Kiya Thompson, RN, a surgical trauma nurse for 20 years, was similarly inspired to share her passion for travel. She is now a certified family travel coach who helps parents plan meaningful trips through her company, LuckyBucky, LLC.

Dx: Self-Esteem Deficiency / Rx: Vivaldi in Venice

In June 2015, Thompson found herself at an all-time low. As a nurse, she felt confident that she was “built for the adrenaline rush and could take on anything.” But outside the trauma center, Thompson felt inadequate, her self-esteem eroded by years of abusive relationships. “The daily hardships of my personal life, combined with the mental fortitude it took to endure the demands of caring for the sickest of the sick, were incredibly weighty,” she recalled.

To escape, Thompson booked her first solo trip: 3 weeks in Italy. But days after she arrived, she felt the need to “escape her escape.” On a bus in Naples, she was pick-pocketed. The man she had been dating before her trip stopped responding to her messages. In her hotel room in Venice, she felt “lost, alone, and helpless.”

One evening, Thompson attended a small orchestral performance of Vivaldi’s “The Four Seasons” in a centuries-old church. The music triggered memories of her Italian grandparents at whose home she’d listened to the same piece.

“A switch flipped, and I changed my whole outlook,” she remembers.

During the concert, she reflected on strangers who had shown her kindness and care. A Canadian man who gave her €50 after her wallet was stolen. A friend-of-a-friend who showed her around Rome. The clerk at her Venice hotel who had offered her a hug.

“In the wake of experiencing the worst of people, I’d experienced so much more of the best of people; strangers who were willing to go above and beyond to help me,” Thompson said.

When Thompson returned home, she brought her new mindset along. “ My ability to problem-solve my way through a solo trip that presented unexpected hardships empowered me,” she explained. “I learned I was much more capable than I’d thought.”

Dx: Wilderness Phobia / Rx: A Safari in Tanzania

On an evening in the mid-1990s, Funt was alone in a tent on a budget camping safari in Tanzania. Animals roared threateningly outside the thin walls. Earlier that day, a vulture had ripped a sandwich out of her hands. Funt was frightened to the core. Worrying that she’d be the next meal for the local wildlife, she started to sob. “This was as raw as I had ever gotten at that point in my life,” she said.

Suddenly, Funt said her brain shifted into problem-solving mode. She made one small decision: To switch to a different Jeep for the next day’s excursion. Having made a seemingly insignificant choice, she felt calmer and no longer like a victim. It brought control. Instead of worrying, she began looking forward to the wildlife she would see.

In the morning, in the new Jeep, she befriended a nurse from Canada. Together, they visited the Maasai Mara tribe and nearby pubs, meeting members of the community.

“It was the most exciting experience of my life,” Funt said. “And it had started with me crying.”

Dx: Parenting-itis / Rx: A Mountain Getaway

As Thompson pointed out, sometimes the destination is secondary to the intension behind a trip. And the quality of the time away matters more than how long you can stay. After becoming parents 4 years ago, Thompson and her husband hadn’t traveled alone together. Like many parents of young children, they were short on time to relax and reconnect as a couple.

So Thompson planned a weekend trip to an isolated cabin in the Massanutten Mountain Range within the George Washington National Forest, about a 2-hour drive from their Washington, DC, area home.

“We put our devices away and focused on being completely present with one another,” said Thompson. The couple took a walk in the woods, where “all we could hear were drops of water from the snowmelt, the crunch of the snow beneath our feet, and the occasional bird looking for food,” she recalled. “There were no cars, no other people. It was quiet, calm, and incredibly peaceful.”

Whether sitting by the fire, soaking in the outdoor hot tub, or playing card games, “our conversation didn’t surround what we’d have for dinner or who would do baths and bedtime with whom,” Thompson said. “We didn’t talk about work, upcoming commitments, or items on our to-do lists.” The getaway was so refreshing, the couple intend to repeat the trip each year.

Dx: Persistent Grief / Rx: Hiking and Hinduism in Nepal

Nearly 3 years ago, Funt experienced a 2-month period where both of her kids left for college and both her father and father-in-law passed away. Besieged by grief, she found herself questioning whether her best years were behind her. She was also grappling with her mortality, because she was then approaching 59, the age at which her own mother had died. So Funt decided to go trekking in Nepal. “I am a traveler — it’s what I do,” she said.

Having the trip to prepare for changed Funt’s whole outlook, she remembers. Throwing herself into the planning helped her transcend her grief. But being in Nepal was even more impactful. She and her husband spent hours trekking through majestic mountain ranges, which “touched their souls.” At a crematorium, they learned about Hindu beliefs on death, which helped them with the grieving process.

The trip “lifted me so high up on so many levels and brought me back to my authentic self,” Funt said. On her flight home from Kathmandu, she decided to start her travel business.

“I needed something else [in addition to radiology] to put my passion, heart, and creativity into, and it would be another way of doing service,” she explained.

Dx: Couch Potato Syndrome / Rx: Planning an Adventure

Like all of us, Funt knows exercise is important for health. But that knowledge alone doesn’t motivate her to move, she admitted. What does get her off the couch is scheduling an active trip — and then training for it. “When I have a goal tied to my values of adventure, connection, and community, fear will set in if I don’t start to move,” she said. It was after booking her Nepal trip (which included an 8-mile, 3000-foot trek) that Funt started getting in shape.

Travel has motivated Funt’s clients in similar ways. Last year, 8 months before one of her Morocco trips, Funt spoke over Zoom with a woman who’d just enrolled. This woman told her she’d signed up in order to commit to her health.

By the time Funt saw her again, on day 1 of the trip, the woman had lost 50 pounds. “It was the greatest transformation,” Funt recalled. “On the trip, she was the first one up the mountain and beamed the whole time. It was beautiful to watch her reclaim her power, body, and life.”

Getting Lost — Finding Inspiration

Since Thompson’s trip to Italy, she has traveled extensively, visiting nearly 25 countries. “Traveling inspired me to continue exploring the world and myself,” she said.

Since leading her first trip to Morocco in 2023, Funt said she’s received more letters of appreciation from her clients than her patients. The results from this type of travel therapy can be dramatic.

After a trip with Funt, one burned-out physician decided that she needed to find a job with a better work-life balance. An empty nester realized the “feeling of belonging and community” on the trip was what had been missing in her “regular” life. After returning home, she began rekindling relationships with old friends.

To many, a vacation is a treat. But, as Funt and Thompson have learned firsthand, it can also be a prescription — for ennui, sadness, loneliness, and all the physical issues that come with them. Sometimes, going far away helps you come home to yourself.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Scholarly Activity Among VA Podiatrists: A Cross-Sectional Study

Scholarly Activity Among VA Podiatrists: A Cross-Sectional Study

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) delivers care to > 9 million veterans, including primary and specialty care.1 While clinical duties remain important across the health system, proposed productivity models have included clinician research activity, given that many hold roles in academia.2 Within this framework, research plays a pivotal role in advancing clinical practices and outcomes. Studies have found that physicians who participated in research report higher job satisfaction.3

As a specialty within the VA, podiatrists diagnose, treat, and prevent foot and ankle disorders. In addition to clinical practice, various scholarly activities are shared among these physicians.4 Reasons for scholarly pursuits among podiatrists vary, including participation in research for academic promotion or to establish expertise in a given area.4-7 Although research remains a component associated with promotion within the VA, little is known about the scholarly activity of VA podiatrists. Specifically, there remains a paucity of data concerning their expertise, as evidenced through peer-reviewed publications, among these physicians and surgeons. To date, no analysis of scholarly activity among VA podiatrists has been conducted.

The primary aim of this investigation was to describe the scholarly productivity among podiatrists employed by the VA through an analysis of the number of peer-reviewed publications and the respective h-index of each physician. The secondary aim of this investigation was to assess the effect of academic productivity on compensation. This study describes research activities pursued by VA physicians and provides the veteran patient population with the confidence that their foot health care remains in the hands of experts within the field.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Feds Data Center (www.fedsdatacenter.com) online database of employees was used to identify VA podiatrists on June 17, 2024. All GS-15 physicians and their respective salaries in fiscal year 2023 were recorded. Administratively determined employees, including residents, were excluded. The h-index and number of published documents from any point during a physician’s training or career were reported for each podiatrist using Scopus; podiatrists without an h-index or publication were excluded. 8 Among podiatrists with scholarly activity, this analysis collected academic appointment, sex, and region of practice.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics, presented as counts and frequencies, were used. The median and IQR were used to describe the number of publications and h-index due to their nonnormal distribution. A Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare median publication counts and h-index values among for junior faculty (JF), which includes instructors and assistant professors; senior faculty (SF), which includes associate professors and professors; and those with no academic affiliation (NF). Salary was reported as mean (SD) as it remained normally distributed and was compared using analysis of variance with posthoc Tukey test to increase statistical power. Additionally, this analysis used linear regression to investigate the relationship between scholarly activity and salary. The threshold for statistical significance was set at P < .05.

RESULTS

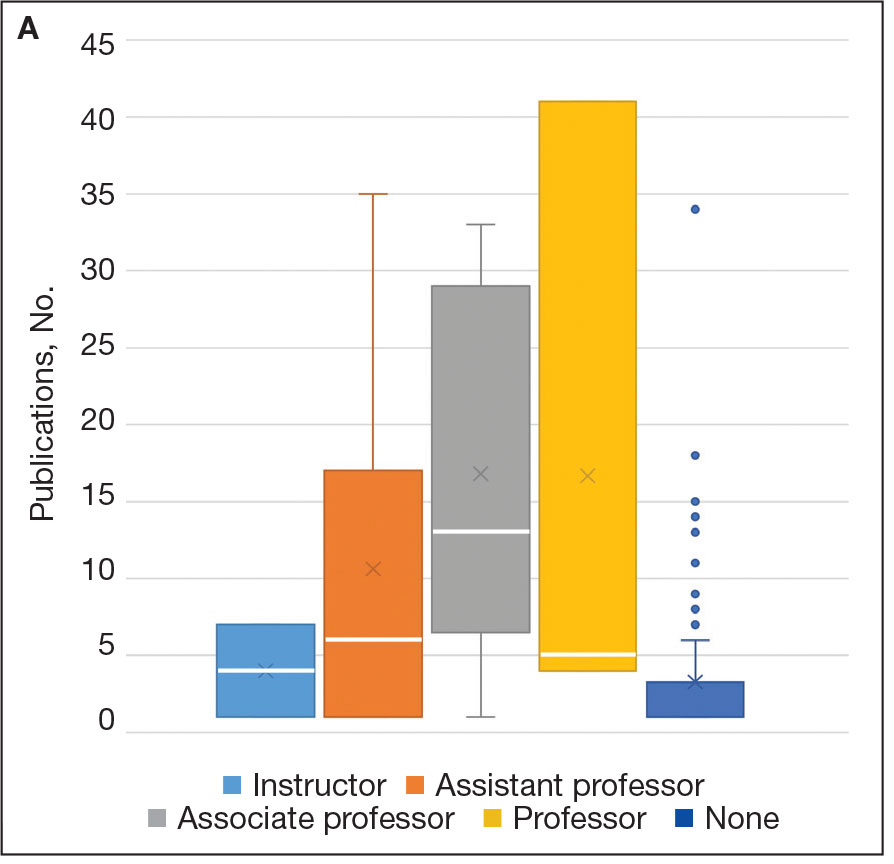

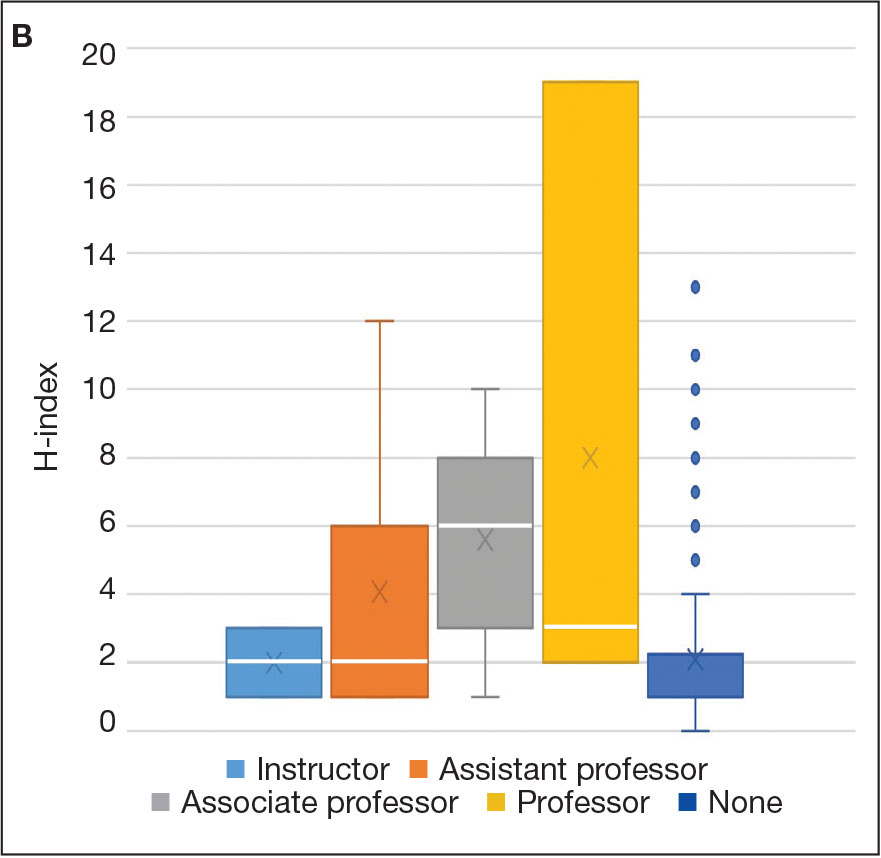

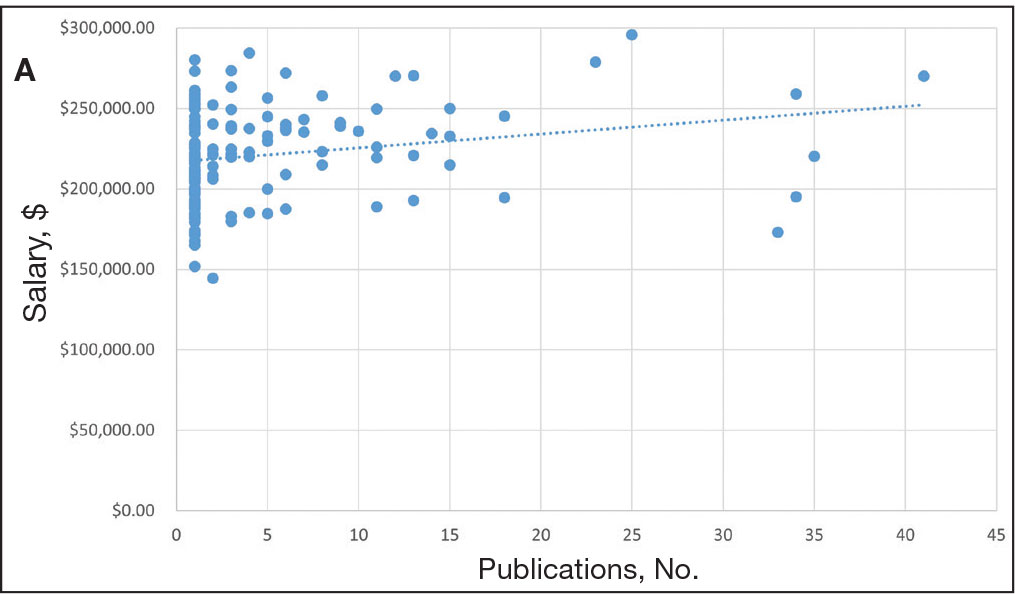

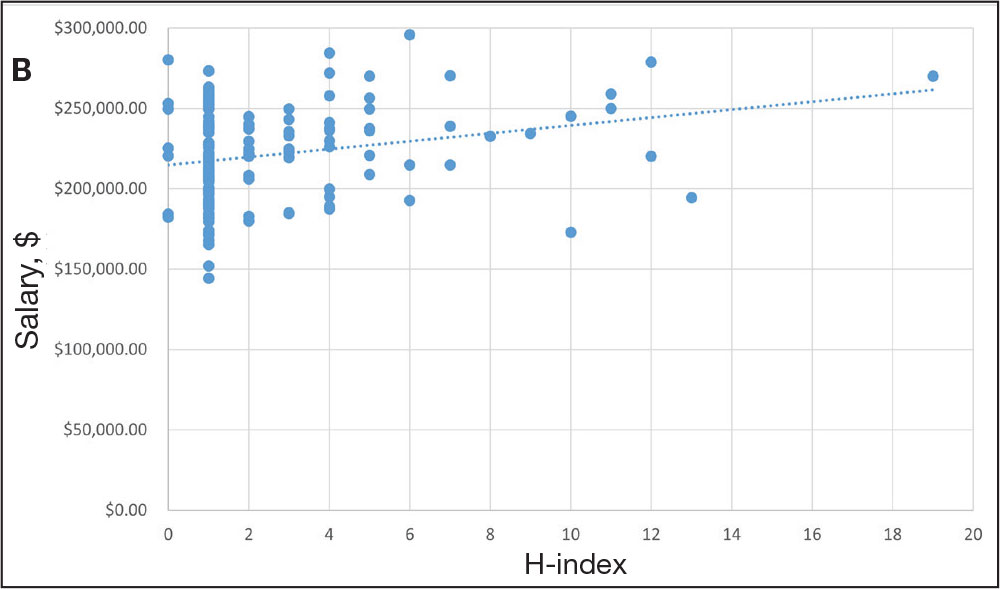

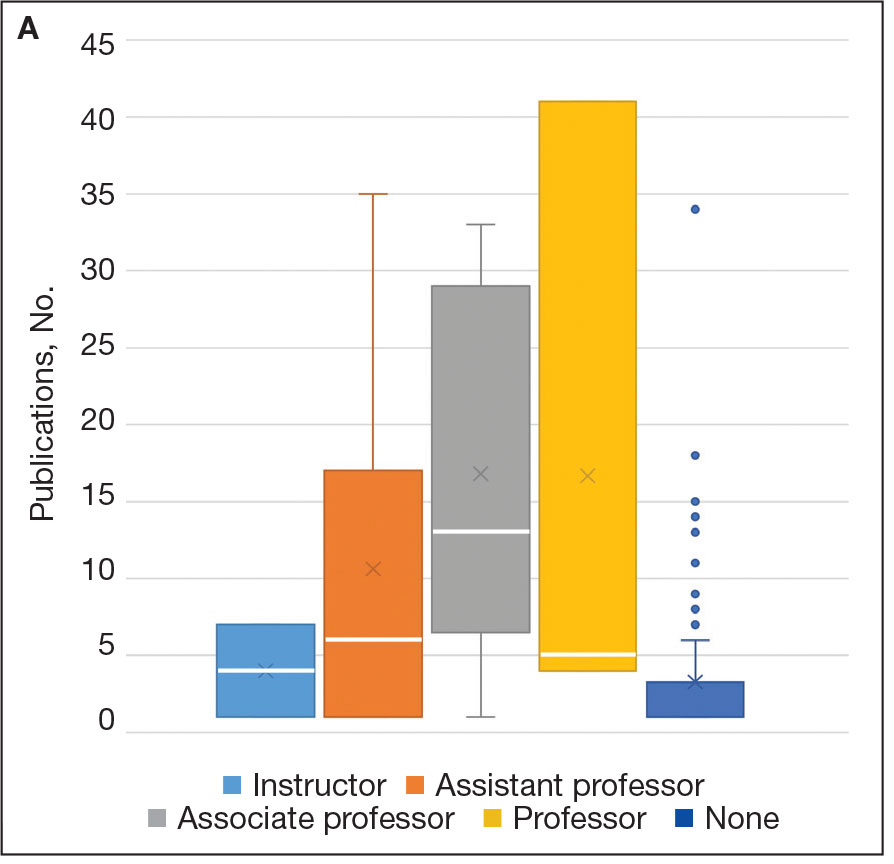

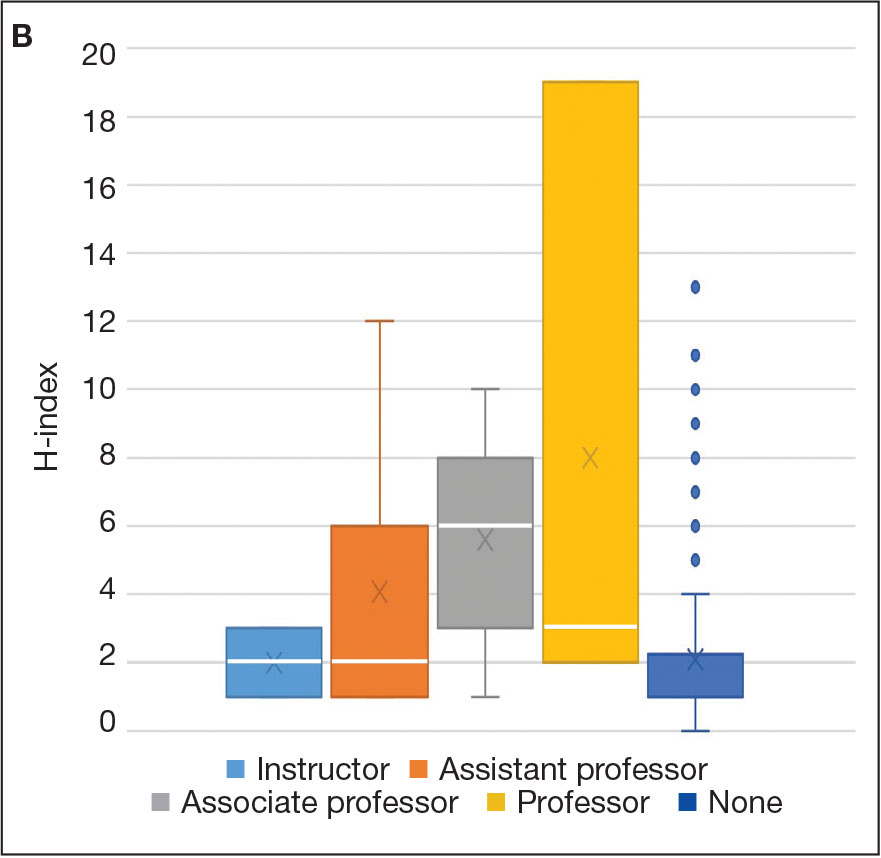

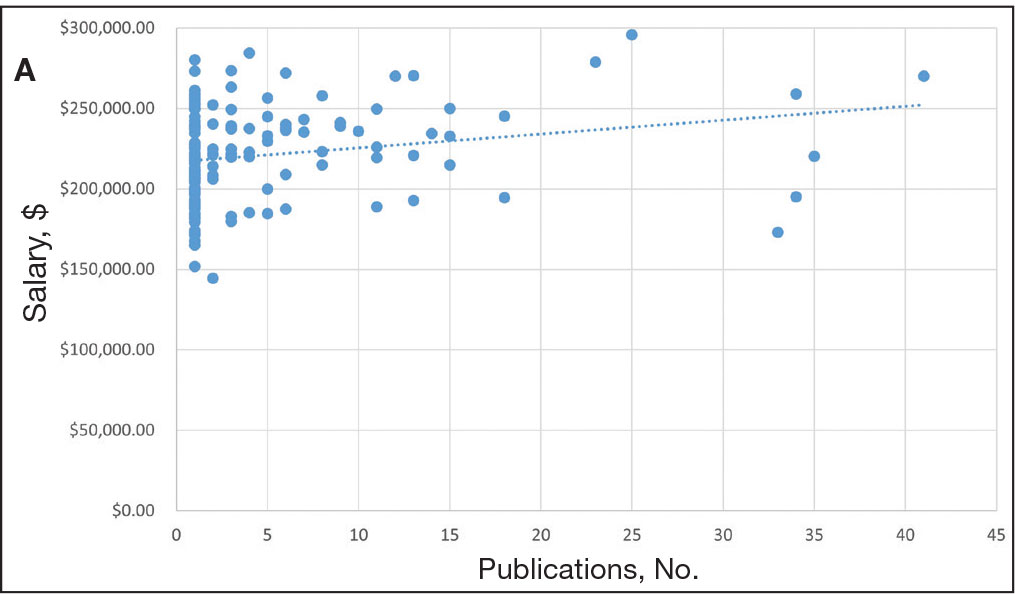

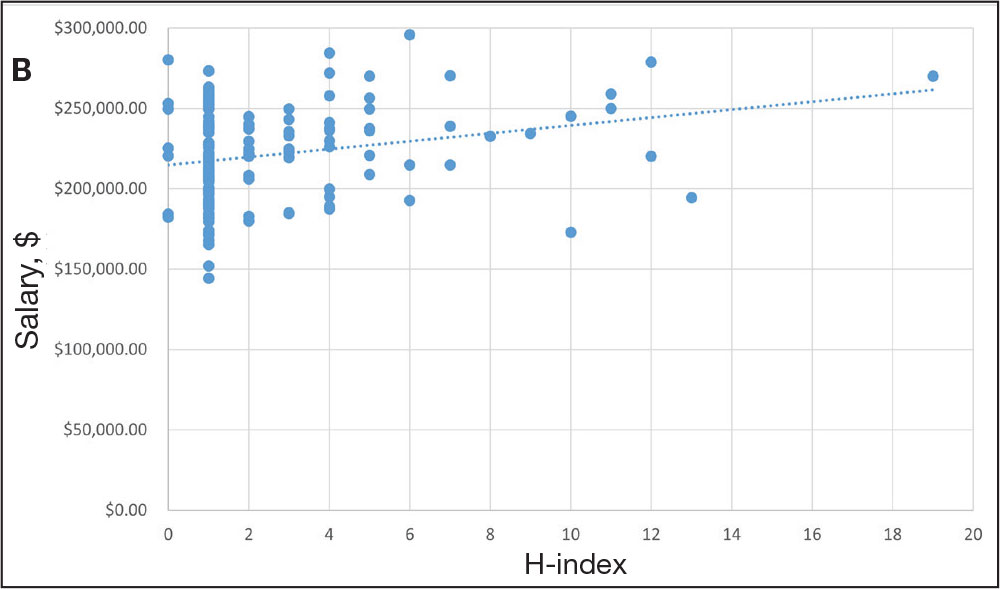

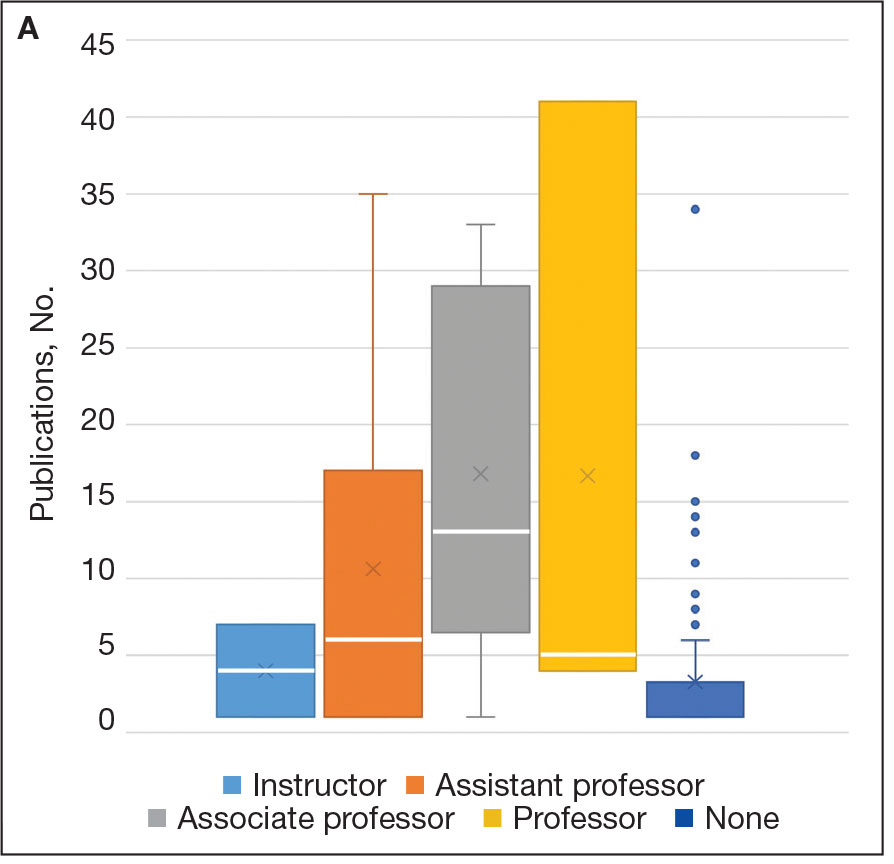

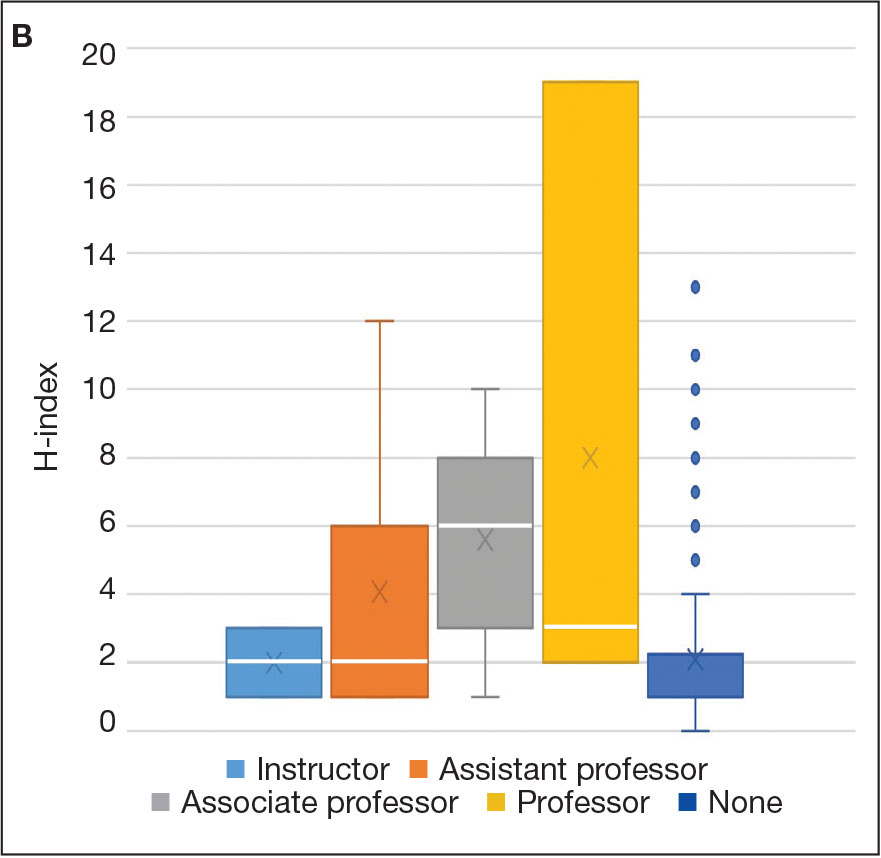

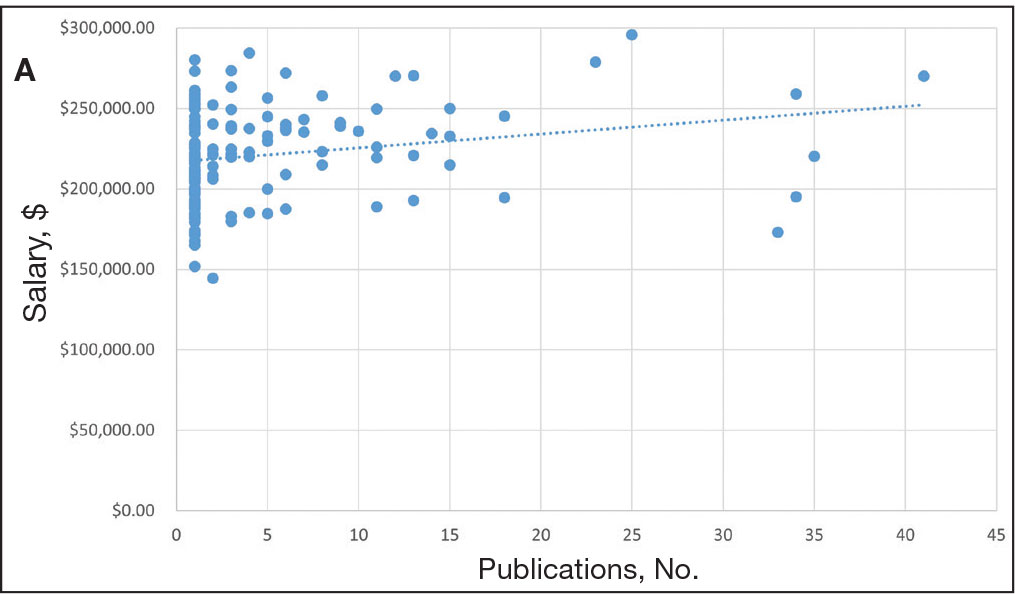

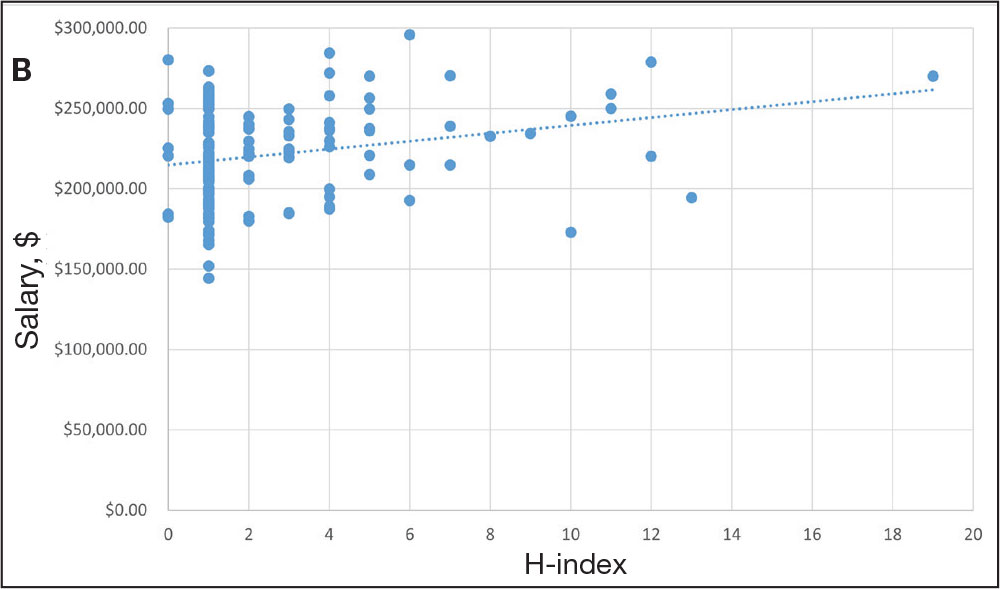

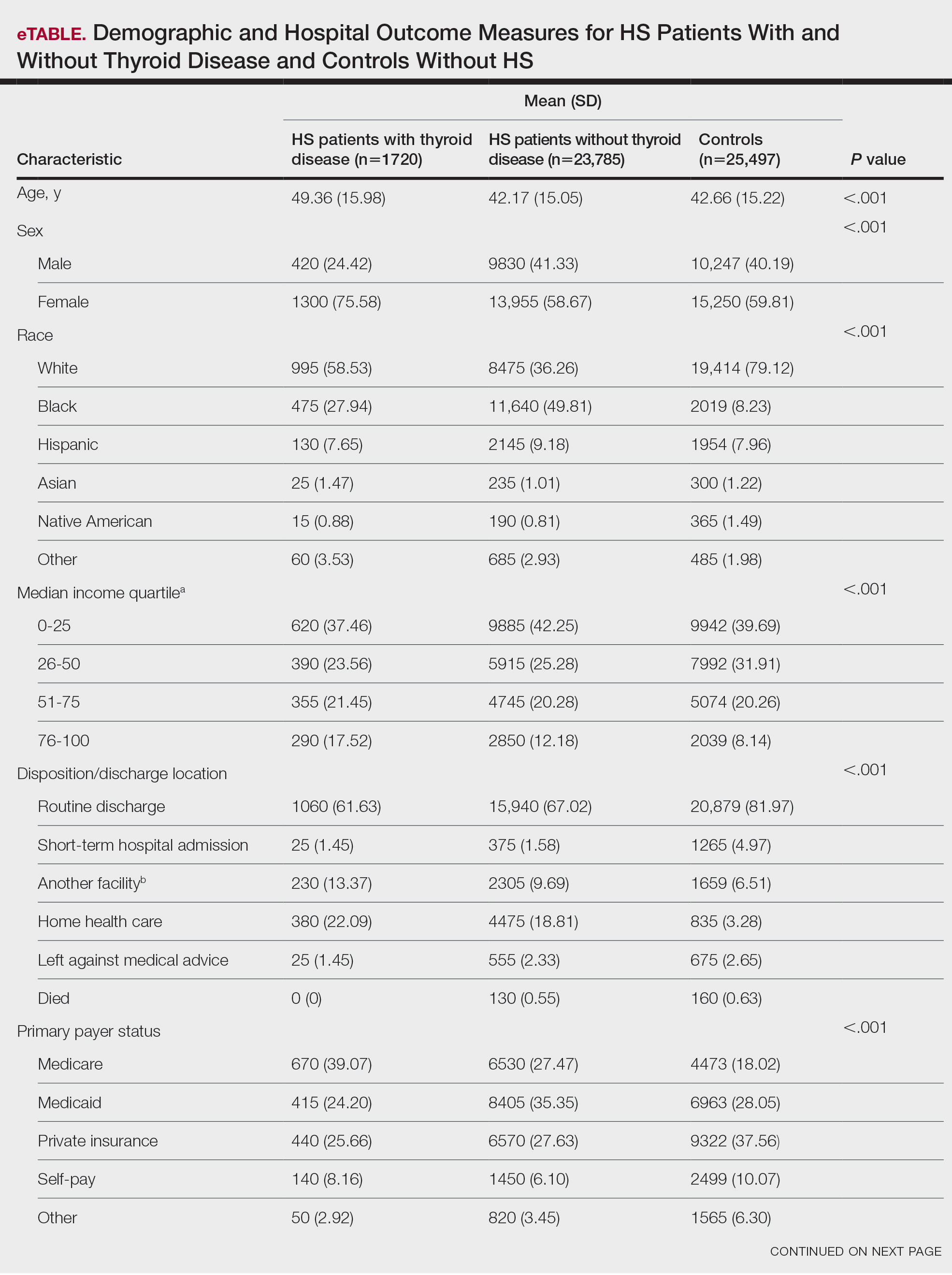

Among 819 VA podiatrists, 150 were administratively determined and excluded, and 512 were excluded for no history of publications, leaving 157 eligible for analysis (Table). A statistically significant difference was found in median (IQR) publication count by faculty appointment. JF had 6.0 (9.5), SF had 12.5 (22.3), and NF had 1.0 (2.0) publication(s) (P < .001) (Figure 1A). There was a statistically significant difference in h-index by faculty appointment. The median (IQR) h-index for JF was 2.0 (3.5), for SF was 5.5 (4.25), and for NF was 1.0 (2.0) (P = .002) (Figure 1B). Salary was not significantly associated with publication count (P = .20) or h-index (P = .62) (Figure 2). No statistically significant difference was found between academic appointment and mean (SD) salary. JF had a median (IQR) salary of $224,063 (27,989), SF of $234,260 (42,963), and NF of $219,811 (P = .35).

(B) h-index.a

aBox sizes indicate IQR (bottom, IQR 1; top, IQR 3); whiskers indicate minimum and maximum within 1.5 x IQR; Xs indicate means; white

lines indicate medians; and dots indicate outliers.

(B) h-index.a

aBox sizes indicate IQR (bottom, IQR 1; top, IQR 3); whiskers indicate minimum and maximum within 1.5 x IQR; Xs indicate means; white

lines indicate medians; and dots indicate outliers.

DISCUSSION

Focused on providing high-quality care, VA physicians use their expertise to practice comprehensive and specialized care.9,10 A cornerstone to this expertise is scholarly activity that contributes to the body of knowledge and, ultimately, the evidence-based medicine by which these physicians practice.11 With veterans considering VA care, it is important to highlight the commitment and dedication to the science and the practice of medicine. This analysis describes the scholarly activity of VA podiatrists and underscores the expertise veterans will receive for the diagnosis and treatment of their foot and ankle pathology.

were not part of an academic facility, a finding that may encourage further action to increase academic productivity in this specialty. For example, collaboration through academic affiliations has been seen throughout VA medical and surgical specialties and provides many benefits. Beginning with graduate medical education, the VA serves as a tremendous resource for resident training.12 Additionally, veterans who sought emergency care at the VA had a lower risk of death than those treated at non-VA hospitals.13 In podiatric medicine and surgery, scholarly activity has been linked to improved outcomes, particularly in the study of ulceration development and its role in either prolonging or preventing amputation.14

Beyond improving clinical outcomes and patient care, engagement in research and inquiry offers other benefits. A cross-sectional study of 7734 physicians within the VA found that research involvement was associated with more favorable job characteristics and job satisfaction perceptions. 3 While this analysis found that about 19% of podiatrists have published once in their career, it remains likely that more may continue to engage in research during their VA tenure. Although this finding shows that an appreciable number of VA podiatrists have published in their field of study, it also encourages departments to provide resources to engage in research. Similar to previous research among foot and ankle surgeons, this analysis also found an increase in publications and h-index as tenure increased.4 Unlike previous research, which found h-index and academic appointment to be contributors to VA dermatologists’ salaries, no significant difference in salary was found in this study associated with publications, h-index, or academic role.15 Although the increase was not statistically significant, salary tended to rise as these variables increased.

Limitations

This analysis was confined to the most recent year of available data, which may not fully capture the longitudinal academic contributions and trends of individual podiatrists. Academic productivity can fluctuate significantly over time due to various factors, including changes in research focus and administrative responsibilities. The study also relied on Scopus to identify and quantify academic productivity. This database may not include all publications relevant to podiatrists, particularly those in niche or nonindexed journals. Additionally, name variations and potential misspellings could lead to missing data for individual podiatrists’ publications. Furthermore, this study did not account for other significant contributors to salary and career advancement within the federal system. Factors such as clinical performance, administrative duties, patient satisfaction, and contributions to teaching and mentoring are critical elements that also influence career progression and compensation but were not captured in this analysis. The retrospective design of this study inherently limits the ability to establish causal relationships. While associations between academic productivity and certain outcomes may be identified, it is not possible to definitively determine the direction or causality of these relationships. Future research may examine how scholarly activity continues once a clinician is part of VA.

CONCLUSIONS

This study highlights the significant academic contributions of VA podiatrists to research and the medical literature. By fostering an active research environment, the VA can ensure veterans receive the highest quality of care from knowledgeable and expert clinicians. Future research should aim to provide a more comprehensive analysis, capturing long-term trends and considering all factors influencing career advancement in VA.

- Rosland AM, Nelson K, Sun H, et al. The patient-centered medical home in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(7):e263-e272.

- Coleman DL, Moran E, Serfilippi D, et al. Measuring physicians’ productivity in a Veterans’ Affairs Medical Center. Acad Med. 2003;78(7):682-689. doi:10.1097/00001888-200307000-00007

- Mohr DC, Burgess JF Jr. Job characteristics and job satisfaction among physicians involved with research in the Veterans Health Administration. Acad Med. 2011;86(8):938-945. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182223b76

- Casciato DJ, Cravey KS, Barron IM. Scholarly productivity among academic foot and ankle surgeons affiliated with US podiatric medicine and surgery residency and fellowship training programs. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2021;60(6):1222-1226. doi:10.1053/j.jfas.2021.04.017

- Hyer CF, Casciato DJ, Rushing CJ, Schuberth JM. Incidence of scholarly publication by selected content experts presenting at national society foot and ankle meetings from 2016 to 2020. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2022;61(6):1317-1320. doi:10.1053/j.jfas.2022.04.011

- Casciato DJ, Thompson J, Yancovitz S, Chandra A, Prissel MA, Hyer CF. Research activity among foot and ankle surgery fellows: a systematic review. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2021;60(6):1227-1231. doi:10.1053/j.jfas.2021.04.018

- Casciato DJ, Thompson J, Hyer CF. Post-fellowship foot and ankle surgeon research productivity: a systematic review. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2022;61(4):896-899. doi:10.1053/j.jfas.2021.12.028

- Hirsch JE. An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(46):16569-16572. doi:10.1073/pnas.0507655102

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans Health Administration. About VHA. Updated January 20, 2025. Accessed February 17, 2025. https://www.va.gov/health/aboutvha.asp

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA National Center for Patient Safety. About Us. Updated November 29, 2023. Accessed February 17, 2025. https://www.patientsafety.va.gov/

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines. Updated February 7, 2025. Accessed February 17, 2025. https://www.healthquality.va.gov

- Ravin AG, Gottlieb NB, Wang HT, et al. Effect of the Veterans Affairs Medical System on plastic surgery residency training. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(2):656-660. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000197216.95544.f7

- Chan DC, Danesh K, Costantini S, Card D, Taylor L, Studdert DM. Mortality among US veterans after emergency visits to Veterans Affairs and other hospitals: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2022;376:e068099. doi:10.1136/bmj-2021-068099

- Gibson LW, Abbas A. Limb salvage for veterans with diabetes: to care for him who has borne the battle. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2013;25(1):131-134. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2012.11.004

- Do MH, Lipner SR. Contribution of gender on compensation of Veterans Affairs-affiliated dermatologists: a cross-sectional study. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6(5):414-418. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.09.009

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) delivers care to > 9 million veterans, including primary and specialty care.1 While clinical duties remain important across the health system, proposed productivity models have included clinician research activity, given that many hold roles in academia.2 Within this framework, research plays a pivotal role in advancing clinical practices and outcomes. Studies have found that physicians who participated in research report higher job satisfaction.3

As a specialty within the VA, podiatrists diagnose, treat, and prevent foot and ankle disorders. In addition to clinical practice, various scholarly activities are shared among these physicians.4 Reasons for scholarly pursuits among podiatrists vary, including participation in research for academic promotion or to establish expertise in a given area.4-7 Although research remains a component associated with promotion within the VA, little is known about the scholarly activity of VA podiatrists. Specifically, there remains a paucity of data concerning their expertise, as evidenced through peer-reviewed publications, among these physicians and surgeons. To date, no analysis of scholarly activity among VA podiatrists has been conducted.

The primary aim of this investigation was to describe the scholarly productivity among podiatrists employed by the VA through an analysis of the number of peer-reviewed publications and the respective h-index of each physician. The secondary aim of this investigation was to assess the effect of academic productivity on compensation. This study describes research activities pursued by VA physicians and provides the veteran patient population with the confidence that their foot health care remains in the hands of experts within the field.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Feds Data Center (www.fedsdatacenter.com) online database of employees was used to identify VA podiatrists on June 17, 2024. All GS-15 physicians and their respective salaries in fiscal year 2023 were recorded. Administratively determined employees, including residents, were excluded. The h-index and number of published documents from any point during a physician’s training or career were reported for each podiatrist using Scopus; podiatrists without an h-index or publication were excluded. 8 Among podiatrists with scholarly activity, this analysis collected academic appointment, sex, and region of practice.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics, presented as counts and frequencies, were used. The median and IQR were used to describe the number of publications and h-index due to their nonnormal distribution. A Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare median publication counts and h-index values among for junior faculty (JF), which includes instructors and assistant professors; senior faculty (SF), which includes associate professors and professors; and those with no academic affiliation (NF). Salary was reported as mean (SD) as it remained normally distributed and was compared using analysis of variance with posthoc Tukey test to increase statistical power. Additionally, this analysis used linear regression to investigate the relationship between scholarly activity and salary. The threshold for statistical significance was set at P < .05.

RESULTS

Among 819 VA podiatrists, 150 were administratively determined and excluded, and 512 were excluded for no history of publications, leaving 157 eligible for analysis (Table). A statistically significant difference was found in median (IQR) publication count by faculty appointment. JF had 6.0 (9.5), SF had 12.5 (22.3), and NF had 1.0 (2.0) publication(s) (P < .001) (Figure 1A). There was a statistically significant difference in h-index by faculty appointment. The median (IQR) h-index for JF was 2.0 (3.5), for SF was 5.5 (4.25), and for NF was 1.0 (2.0) (P = .002) (Figure 1B). Salary was not significantly associated with publication count (P = .20) or h-index (P = .62) (Figure 2). No statistically significant difference was found between academic appointment and mean (SD) salary. JF had a median (IQR) salary of $224,063 (27,989), SF of $234,260 (42,963), and NF of $219,811 (P = .35).

(B) h-index.a

aBox sizes indicate IQR (bottom, IQR 1; top, IQR 3); whiskers indicate minimum and maximum within 1.5 x IQR; Xs indicate means; white

lines indicate medians; and dots indicate outliers.

(B) h-index.a

aBox sizes indicate IQR (bottom, IQR 1; top, IQR 3); whiskers indicate minimum and maximum within 1.5 x IQR; Xs indicate means; white

lines indicate medians; and dots indicate outliers.

DISCUSSION

Focused on providing high-quality care, VA physicians use their expertise to practice comprehensive and specialized care.9,10 A cornerstone to this expertise is scholarly activity that contributes to the body of knowledge and, ultimately, the evidence-based medicine by which these physicians practice.11 With veterans considering VA care, it is important to highlight the commitment and dedication to the science and the practice of medicine. This analysis describes the scholarly activity of VA podiatrists and underscores the expertise veterans will receive for the diagnosis and treatment of their foot and ankle pathology.

were not part of an academic facility, a finding that may encourage further action to increase academic productivity in this specialty. For example, collaboration through academic affiliations has been seen throughout VA medical and surgical specialties and provides many benefits. Beginning with graduate medical education, the VA serves as a tremendous resource for resident training.12 Additionally, veterans who sought emergency care at the VA had a lower risk of death than those treated at non-VA hospitals.13 In podiatric medicine and surgery, scholarly activity has been linked to improved outcomes, particularly in the study of ulceration development and its role in either prolonging or preventing amputation.14

Beyond improving clinical outcomes and patient care, engagement in research and inquiry offers other benefits. A cross-sectional study of 7734 physicians within the VA found that research involvement was associated with more favorable job characteristics and job satisfaction perceptions. 3 While this analysis found that about 19% of podiatrists have published once in their career, it remains likely that more may continue to engage in research during their VA tenure. Although this finding shows that an appreciable number of VA podiatrists have published in their field of study, it also encourages departments to provide resources to engage in research. Similar to previous research among foot and ankle surgeons, this analysis also found an increase in publications and h-index as tenure increased.4 Unlike previous research, which found h-index and academic appointment to be contributors to VA dermatologists’ salaries, no significant difference in salary was found in this study associated with publications, h-index, or academic role.15 Although the increase was not statistically significant, salary tended to rise as these variables increased.

Limitations

This analysis was confined to the most recent year of available data, which may not fully capture the longitudinal academic contributions and trends of individual podiatrists. Academic productivity can fluctuate significantly over time due to various factors, including changes in research focus and administrative responsibilities. The study also relied on Scopus to identify and quantify academic productivity. This database may not include all publications relevant to podiatrists, particularly those in niche or nonindexed journals. Additionally, name variations and potential misspellings could lead to missing data for individual podiatrists’ publications. Furthermore, this study did not account for other significant contributors to salary and career advancement within the federal system. Factors such as clinical performance, administrative duties, patient satisfaction, and contributions to teaching and mentoring are critical elements that also influence career progression and compensation but were not captured in this analysis. The retrospective design of this study inherently limits the ability to establish causal relationships. While associations between academic productivity and certain outcomes may be identified, it is not possible to definitively determine the direction or causality of these relationships. Future research may examine how scholarly activity continues once a clinician is part of VA.

CONCLUSIONS

This study highlights the significant academic contributions of VA podiatrists to research and the medical literature. By fostering an active research environment, the VA can ensure veterans receive the highest quality of care from knowledgeable and expert clinicians. Future research should aim to provide a more comprehensive analysis, capturing long-term trends and considering all factors influencing career advancement in VA.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) delivers care to > 9 million veterans, including primary and specialty care.1 While clinical duties remain important across the health system, proposed productivity models have included clinician research activity, given that many hold roles in academia.2 Within this framework, research plays a pivotal role in advancing clinical practices and outcomes. Studies have found that physicians who participated in research report higher job satisfaction.3

As a specialty within the VA, podiatrists diagnose, treat, and prevent foot and ankle disorders. In addition to clinical practice, various scholarly activities are shared among these physicians.4 Reasons for scholarly pursuits among podiatrists vary, including participation in research for academic promotion or to establish expertise in a given area.4-7 Although research remains a component associated with promotion within the VA, little is known about the scholarly activity of VA podiatrists. Specifically, there remains a paucity of data concerning their expertise, as evidenced through peer-reviewed publications, among these physicians and surgeons. To date, no analysis of scholarly activity among VA podiatrists has been conducted.

The primary aim of this investigation was to describe the scholarly productivity among podiatrists employed by the VA through an analysis of the number of peer-reviewed publications and the respective h-index of each physician. The secondary aim of this investigation was to assess the effect of academic productivity on compensation. This study describes research activities pursued by VA physicians and provides the veteran patient population with the confidence that their foot health care remains in the hands of experts within the field.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Feds Data Center (www.fedsdatacenter.com) online database of employees was used to identify VA podiatrists on June 17, 2024. All GS-15 physicians and their respective salaries in fiscal year 2023 were recorded. Administratively determined employees, including residents, were excluded. The h-index and number of published documents from any point during a physician’s training or career were reported for each podiatrist using Scopus; podiatrists without an h-index or publication were excluded. 8 Among podiatrists with scholarly activity, this analysis collected academic appointment, sex, and region of practice.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics, presented as counts and frequencies, were used. The median and IQR were used to describe the number of publications and h-index due to their nonnormal distribution. A Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare median publication counts and h-index values among for junior faculty (JF), which includes instructors and assistant professors; senior faculty (SF), which includes associate professors and professors; and those with no academic affiliation (NF). Salary was reported as mean (SD) as it remained normally distributed and was compared using analysis of variance with posthoc Tukey test to increase statistical power. Additionally, this analysis used linear regression to investigate the relationship between scholarly activity and salary. The threshold for statistical significance was set at P < .05.

RESULTS

Among 819 VA podiatrists, 150 were administratively determined and excluded, and 512 were excluded for no history of publications, leaving 157 eligible for analysis (Table). A statistically significant difference was found in median (IQR) publication count by faculty appointment. JF had 6.0 (9.5), SF had 12.5 (22.3), and NF had 1.0 (2.0) publication(s) (P < .001) (Figure 1A). There was a statistically significant difference in h-index by faculty appointment. The median (IQR) h-index for JF was 2.0 (3.5), for SF was 5.5 (4.25), and for NF was 1.0 (2.0) (P = .002) (Figure 1B). Salary was not significantly associated with publication count (P = .20) or h-index (P = .62) (Figure 2). No statistically significant difference was found between academic appointment and mean (SD) salary. JF had a median (IQR) salary of $224,063 (27,989), SF of $234,260 (42,963), and NF of $219,811 (P = .35).

(B) h-index.a

aBox sizes indicate IQR (bottom, IQR 1; top, IQR 3); whiskers indicate minimum and maximum within 1.5 x IQR; Xs indicate means; white

lines indicate medians; and dots indicate outliers.

(B) h-index.a

aBox sizes indicate IQR (bottom, IQR 1; top, IQR 3); whiskers indicate minimum and maximum within 1.5 x IQR; Xs indicate means; white

lines indicate medians; and dots indicate outliers.

DISCUSSION

Focused on providing high-quality care, VA physicians use their expertise to practice comprehensive and specialized care.9,10 A cornerstone to this expertise is scholarly activity that contributes to the body of knowledge and, ultimately, the evidence-based medicine by which these physicians practice.11 With veterans considering VA care, it is important to highlight the commitment and dedication to the science and the practice of medicine. This analysis describes the scholarly activity of VA podiatrists and underscores the expertise veterans will receive for the diagnosis and treatment of their foot and ankle pathology.

were not part of an academic facility, a finding that may encourage further action to increase academic productivity in this specialty. For example, collaboration through academic affiliations has been seen throughout VA medical and surgical specialties and provides many benefits. Beginning with graduate medical education, the VA serves as a tremendous resource for resident training.12 Additionally, veterans who sought emergency care at the VA had a lower risk of death than those treated at non-VA hospitals.13 In podiatric medicine and surgery, scholarly activity has been linked to improved outcomes, particularly in the study of ulceration development and its role in either prolonging or preventing amputation.14

Beyond improving clinical outcomes and patient care, engagement in research and inquiry offers other benefits. A cross-sectional study of 7734 physicians within the VA found that research involvement was associated with more favorable job characteristics and job satisfaction perceptions. 3 While this analysis found that about 19% of podiatrists have published once in their career, it remains likely that more may continue to engage in research during their VA tenure. Although this finding shows that an appreciable number of VA podiatrists have published in their field of study, it also encourages departments to provide resources to engage in research. Similar to previous research among foot and ankle surgeons, this analysis also found an increase in publications and h-index as tenure increased.4 Unlike previous research, which found h-index and academic appointment to be contributors to VA dermatologists’ salaries, no significant difference in salary was found in this study associated with publications, h-index, or academic role.15 Although the increase was not statistically significant, salary tended to rise as these variables increased.

Limitations

This analysis was confined to the most recent year of available data, which may not fully capture the longitudinal academic contributions and trends of individual podiatrists. Academic productivity can fluctuate significantly over time due to various factors, including changes in research focus and administrative responsibilities. The study also relied on Scopus to identify and quantify academic productivity. This database may not include all publications relevant to podiatrists, particularly those in niche or nonindexed journals. Additionally, name variations and potential misspellings could lead to missing data for individual podiatrists’ publications. Furthermore, this study did not account for other significant contributors to salary and career advancement within the federal system. Factors such as clinical performance, administrative duties, patient satisfaction, and contributions to teaching and mentoring are critical elements that also influence career progression and compensation but were not captured in this analysis. The retrospective design of this study inherently limits the ability to establish causal relationships. While associations between academic productivity and certain outcomes may be identified, it is not possible to definitively determine the direction or causality of these relationships. Future research may examine how scholarly activity continues once a clinician is part of VA.

CONCLUSIONS

This study highlights the significant academic contributions of VA podiatrists to research and the medical literature. By fostering an active research environment, the VA can ensure veterans receive the highest quality of care from knowledgeable and expert clinicians. Future research should aim to provide a more comprehensive analysis, capturing long-term trends and considering all factors influencing career advancement in VA.

- Rosland AM, Nelson K, Sun H, et al. The patient-centered medical home in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(7):e263-e272.

- Coleman DL, Moran E, Serfilippi D, et al. Measuring physicians’ productivity in a Veterans’ Affairs Medical Center. Acad Med. 2003;78(7):682-689. doi:10.1097/00001888-200307000-00007

- Mohr DC, Burgess JF Jr. Job characteristics and job satisfaction among physicians involved with research in the Veterans Health Administration. Acad Med. 2011;86(8):938-945. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182223b76

- Casciato DJ, Cravey KS, Barron IM. Scholarly productivity among academic foot and ankle surgeons affiliated with US podiatric medicine and surgery residency and fellowship training programs. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2021;60(6):1222-1226. doi:10.1053/j.jfas.2021.04.017