User login

Turning the Cancer Research Problem Into an Opportunity

Turning the Cancer Research Problem Into an Opportunity

The War on Cancer, declared by President Richard Nixon some 50 years ago, has been canceled during the second Trump administration in 2025 — so saith The New York Times Sunday magazine cover story on September 14, 2025. This war seems now to be best described as "The War on Cancer Research."

To our horror and disbelief, we've witnessed the slow but persistent drift of much of the United States citizenry away from science and the sudden and severe movement of the US government to crush much medical research. But it is not as if we were not warned.

In August 2024, on these pages and without political bias, I urged Medscape readers to pay attention to Project 2025. A great deal of what we as a population are now experiencing was laid out as a carefully constructed plan.

What is surprising is the cruel ruthlessness of the "move fast and break things" approach, taken with little apparent concern about the resultant human tragedies (workforce and patients) and no clear care about the resulting fallout. As we've now learned, destroying something as grand as our cancer research enterprise can be accomplished very quickly. Rebuilding it is certain to be slow and difficult and perhaps can never be accomplished.

In this new anti-science, anti-research, and anti-researcher reality, what can we now do?

First and foremost, we must recognize that the war on cancer is not over. Cancer is not canceled, even if much of the US government's research effort/funding has been. Those of us in medicine and public health often speak in quantification of causes of death of our populations. As such, I'll remind Medscape readers that cancer afflicts some 20 million humans worldwide each year, killing nearly 10 million. Although two-thirds of Americans diagnosed with a potentially lethal malignancy are cured, cancer still kills roughly 600,000 Americans each year. Cancer has been the second most frequent cause of death of Americans for 75 years.

Being inevitable and immutable, death itself is not the enemy. We all die. Disease, disability, pain, and human suffering are the real enemies of us all. Cancer maims, pains, diabetes, and torments some 20 million humans worldwide each year. That is a huge humanitarian problem that should be recognized by individuals of all creeds and backgrounds.

With this depletion of our domestic government basic and applied cancer research program, what can we do?

- Think globally and look to the international scientific research enterprises — relying on them, much as they have relied on us.

- Defend the universal importance of reliable and available literature on medical science.

- Continue to translate and apply the vast amount of available published research in clinical practice and publish the results.

- Urge private industries to expand their research budgets into areas of study that may not produce quickly tangible positive bottom-line results.

- Remind the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (for whom chronic diseases seem paramount) that cancer is the second leading American chronic disease by morbidity.

- Redouble efforts of cancer prevention, especially urging the FDA to ban combustible tobacco and strive more diligently to decrease obesity.

- Appeal to our vast philanthropic universe to increase its funding of nonprofit organizations active in the cancer investigation, diagnosis, and management space.

One such 501c3 organization is California-based Cancer Commons. (Disclosure: I named it in 2010 and serve as its editor in chief).

A commons is a space shared by a community to use for the common interest. As we originally envisioned it, a cancer commons is an open access internet location where individuals and organizations (eg, corporations, universities, government agencies, philanthropies) will voluntarily share their data to work together to defeat the common enemy of humans: cancer.

On September 8, 2025, Cancer Commons was the 15th annual Lundberg Institute Lecturer at the Commonwealth Club of California in San Francisco. At the lecture, Cancer Commons founder (and long-term survivor of metastatic malignant melanoma), Jay Martin "Martin" Tenenbaum, PhD, spoke of the need for a cancer commons and the founder's vision. Emma Shtivelman, PhD, the long-time compassionate chief scientist, described some of the thousands of patients with advanced cancer that she has helped — all free of charge. And newly named CEO Clifford Reid, MBA, PhD, used his entrepreneurial prowess to envision an ambitious future.

Cancer Commons has always focused on patients with cancer who are beyond standards of curative care. As Cancer Commons evolves, it anticipates focusing on patients with cancer who are beyond National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines. The organization intends to greatly expand its 1000 patients per year with "high touch" engagement with PhD clinical scientists to many thousands by including artificial intelligence. It plans to extend its N-of-One approach to create new knowledge — especially regarding the hundreds of drugs that are FDA-approved for use in treating cancer but have not been further assessed for the utility in actually treating patients with cancer.

The war on cancer is not over. It remains a persistent foe that causes immense disability, pain, and human suffering. With government support depleted, the burden now shifts to the private sector and philanthropic organizations, such as Cancer Commons, to serve as the new vital infrastructure in the fight for a cure. Now, we must redouble our efforts to ensure that these research endeavors are supported if the US government will not do its part.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The War on Cancer, declared by President Richard Nixon some 50 years ago, has been canceled during the second Trump administration in 2025 — so saith The New York Times Sunday magazine cover story on September 14, 2025. This war seems now to be best described as "The War on Cancer Research."

To our horror and disbelief, we've witnessed the slow but persistent drift of much of the United States citizenry away from science and the sudden and severe movement of the US government to crush much medical research. But it is not as if we were not warned.

In August 2024, on these pages and without political bias, I urged Medscape readers to pay attention to Project 2025. A great deal of what we as a population are now experiencing was laid out as a carefully constructed plan.

What is surprising is the cruel ruthlessness of the "move fast and break things" approach, taken with little apparent concern about the resultant human tragedies (workforce and patients) and no clear care about the resulting fallout. As we've now learned, destroying something as grand as our cancer research enterprise can be accomplished very quickly. Rebuilding it is certain to be slow and difficult and perhaps can never be accomplished.

In this new anti-science, anti-research, and anti-researcher reality, what can we now do?

First and foremost, we must recognize that the war on cancer is not over. Cancer is not canceled, even if much of the US government's research effort/funding has been. Those of us in medicine and public health often speak in quantification of causes of death of our populations. As such, I'll remind Medscape readers that cancer afflicts some 20 million humans worldwide each year, killing nearly 10 million. Although two-thirds of Americans diagnosed with a potentially lethal malignancy are cured, cancer still kills roughly 600,000 Americans each year. Cancer has been the second most frequent cause of death of Americans for 75 years.

Being inevitable and immutable, death itself is not the enemy. We all die. Disease, disability, pain, and human suffering are the real enemies of us all. Cancer maims, pains, diabetes, and torments some 20 million humans worldwide each year. That is a huge humanitarian problem that should be recognized by individuals of all creeds and backgrounds.

With this depletion of our domestic government basic and applied cancer research program, what can we do?

- Think globally and look to the international scientific research enterprises — relying on them, much as they have relied on us.

- Defend the universal importance of reliable and available literature on medical science.

- Continue to translate and apply the vast amount of available published research in clinical practice and publish the results.

- Urge private industries to expand their research budgets into areas of study that may not produce quickly tangible positive bottom-line results.

- Remind the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (for whom chronic diseases seem paramount) that cancer is the second leading American chronic disease by morbidity.

- Redouble efforts of cancer prevention, especially urging the FDA to ban combustible tobacco and strive more diligently to decrease obesity.

- Appeal to our vast philanthropic universe to increase its funding of nonprofit organizations active in the cancer investigation, diagnosis, and management space.

One such 501c3 organization is California-based Cancer Commons. (Disclosure: I named it in 2010 and serve as its editor in chief).

A commons is a space shared by a community to use for the common interest. As we originally envisioned it, a cancer commons is an open access internet location where individuals and organizations (eg, corporations, universities, government agencies, philanthropies) will voluntarily share their data to work together to defeat the common enemy of humans: cancer.

On September 8, 2025, Cancer Commons was the 15th annual Lundberg Institute Lecturer at the Commonwealth Club of California in San Francisco. At the lecture, Cancer Commons founder (and long-term survivor of metastatic malignant melanoma), Jay Martin "Martin" Tenenbaum, PhD, spoke of the need for a cancer commons and the founder's vision. Emma Shtivelman, PhD, the long-time compassionate chief scientist, described some of the thousands of patients with advanced cancer that she has helped — all free of charge. And newly named CEO Clifford Reid, MBA, PhD, used his entrepreneurial prowess to envision an ambitious future.

Cancer Commons has always focused on patients with cancer who are beyond standards of curative care. As Cancer Commons evolves, it anticipates focusing on patients with cancer who are beyond National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines. The organization intends to greatly expand its 1000 patients per year with "high touch" engagement with PhD clinical scientists to many thousands by including artificial intelligence. It plans to extend its N-of-One approach to create new knowledge — especially regarding the hundreds of drugs that are FDA-approved for use in treating cancer but have not been further assessed for the utility in actually treating patients with cancer.

The war on cancer is not over. It remains a persistent foe that causes immense disability, pain, and human suffering. With government support depleted, the burden now shifts to the private sector and philanthropic organizations, such as Cancer Commons, to serve as the new vital infrastructure in the fight for a cure. Now, we must redouble our efforts to ensure that these research endeavors are supported if the US government will not do its part.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The War on Cancer, declared by President Richard Nixon some 50 years ago, has been canceled during the second Trump administration in 2025 — so saith The New York Times Sunday magazine cover story on September 14, 2025. This war seems now to be best described as "The War on Cancer Research."

To our horror and disbelief, we've witnessed the slow but persistent drift of much of the United States citizenry away from science and the sudden and severe movement of the US government to crush much medical research. But it is not as if we were not warned.

In August 2024, on these pages and without political bias, I urged Medscape readers to pay attention to Project 2025. A great deal of what we as a population are now experiencing was laid out as a carefully constructed plan.

What is surprising is the cruel ruthlessness of the "move fast and break things" approach, taken with little apparent concern about the resultant human tragedies (workforce and patients) and no clear care about the resulting fallout. As we've now learned, destroying something as grand as our cancer research enterprise can be accomplished very quickly. Rebuilding it is certain to be slow and difficult and perhaps can never be accomplished.

In this new anti-science, anti-research, and anti-researcher reality, what can we now do?

First and foremost, we must recognize that the war on cancer is not over. Cancer is not canceled, even if much of the US government's research effort/funding has been. Those of us in medicine and public health often speak in quantification of causes of death of our populations. As such, I'll remind Medscape readers that cancer afflicts some 20 million humans worldwide each year, killing nearly 10 million. Although two-thirds of Americans diagnosed with a potentially lethal malignancy are cured, cancer still kills roughly 600,000 Americans each year. Cancer has been the second most frequent cause of death of Americans for 75 years.

Being inevitable and immutable, death itself is not the enemy. We all die. Disease, disability, pain, and human suffering are the real enemies of us all. Cancer maims, pains, diabetes, and torments some 20 million humans worldwide each year. That is a huge humanitarian problem that should be recognized by individuals of all creeds and backgrounds.

With this depletion of our domestic government basic and applied cancer research program, what can we do?

- Think globally and look to the international scientific research enterprises — relying on them, much as they have relied on us.

- Defend the universal importance of reliable and available literature on medical science.

- Continue to translate and apply the vast amount of available published research in clinical practice and publish the results.

- Urge private industries to expand their research budgets into areas of study that may not produce quickly tangible positive bottom-line results.

- Remind the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (for whom chronic diseases seem paramount) that cancer is the second leading American chronic disease by morbidity.

- Redouble efforts of cancer prevention, especially urging the FDA to ban combustible tobacco and strive more diligently to decrease obesity.

- Appeal to our vast philanthropic universe to increase its funding of nonprofit organizations active in the cancer investigation, diagnosis, and management space.

One such 501c3 organization is California-based Cancer Commons. (Disclosure: I named it in 2010 and serve as its editor in chief).

A commons is a space shared by a community to use for the common interest. As we originally envisioned it, a cancer commons is an open access internet location where individuals and organizations (eg, corporations, universities, government agencies, philanthropies) will voluntarily share their data to work together to defeat the common enemy of humans: cancer.

On September 8, 2025, Cancer Commons was the 15th annual Lundberg Institute Lecturer at the Commonwealth Club of California in San Francisco. At the lecture, Cancer Commons founder (and long-term survivor of metastatic malignant melanoma), Jay Martin "Martin" Tenenbaum, PhD, spoke of the need for a cancer commons and the founder's vision. Emma Shtivelman, PhD, the long-time compassionate chief scientist, described some of the thousands of patients with advanced cancer that she has helped — all free of charge. And newly named CEO Clifford Reid, MBA, PhD, used his entrepreneurial prowess to envision an ambitious future.

Cancer Commons has always focused on patients with cancer who are beyond standards of curative care. As Cancer Commons evolves, it anticipates focusing on patients with cancer who are beyond National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines. The organization intends to greatly expand its 1000 patients per year with "high touch" engagement with PhD clinical scientists to many thousands by including artificial intelligence. It plans to extend its N-of-One approach to create new knowledge — especially regarding the hundreds of drugs that are FDA-approved for use in treating cancer but have not been further assessed for the utility in actually treating patients with cancer.

The war on cancer is not over. It remains a persistent foe that causes immense disability, pain, and human suffering. With government support depleted, the burden now shifts to the private sector and philanthropic organizations, such as Cancer Commons, to serve as the new vital infrastructure in the fight for a cure. Now, we must redouble our efforts to ensure that these research endeavors are supported if the US government will not do its part.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Turning the Cancer Research Problem Into an Opportunity

Turning the Cancer Research Problem Into an Opportunity

The Once and Future Veterans Health Administration

The Once and Future Veterans Health Administration

He who thus considers things in their first growth and origin ... will obtain the clearest view of them. Politics, Book I, Part II by Aristotle

Many seasoned observers of federal practice have signaled that the future of US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care is threatened as never before. Political forces and economic interests are siphoning Veterans Health Administration (VHA) capital and human resources into the community with an ineluctable push toward privatization.1

This Veterans Day, the vitality, if not the very viability of veteran health care, is in serious jeopardy, so it seems fitting to review the rationale for having institutions dedicated to the specialized medical treatment of veterans. Aristotle advises us on how to undertake this intellectual exercise in the epigraph. This column will revisit the historical origins of VA medicine to better appreciate the justification of an agency committed to this unique purpose and what may be sacrificed if it is decimated.

The provision of medical care focused on the injuries and illnesses of warriors is as old as war. The ancient Romans had among the first veterans’ hospital, named a valetudinarium. Sick and injured members of the Roman legions received state-of-the-art medical and surgical care from military doctors inside these facilities.2

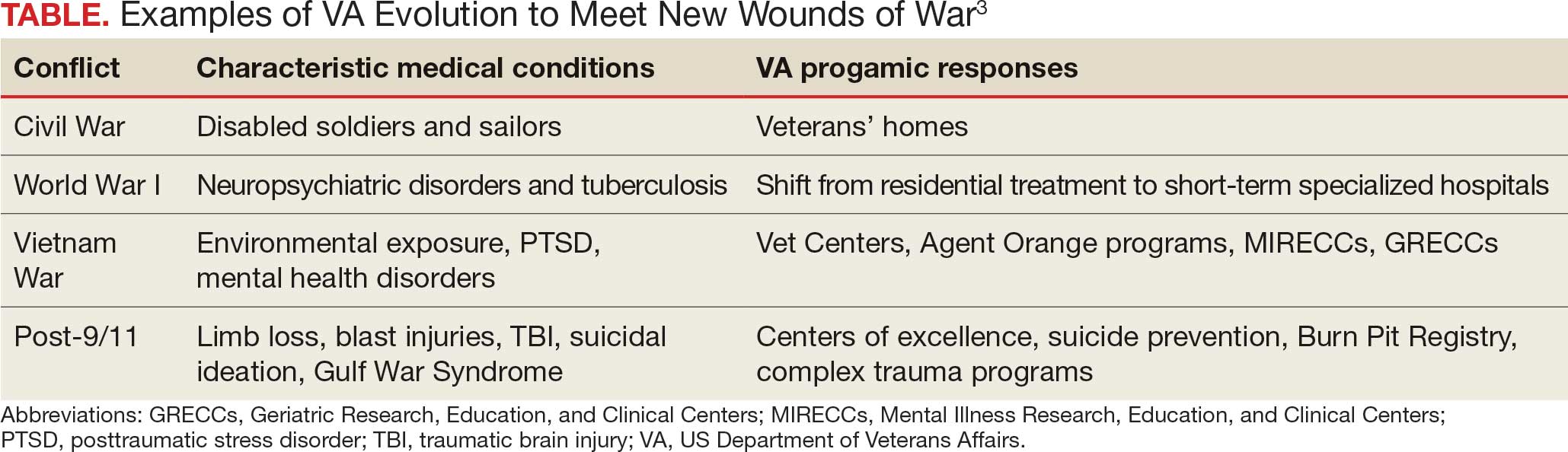

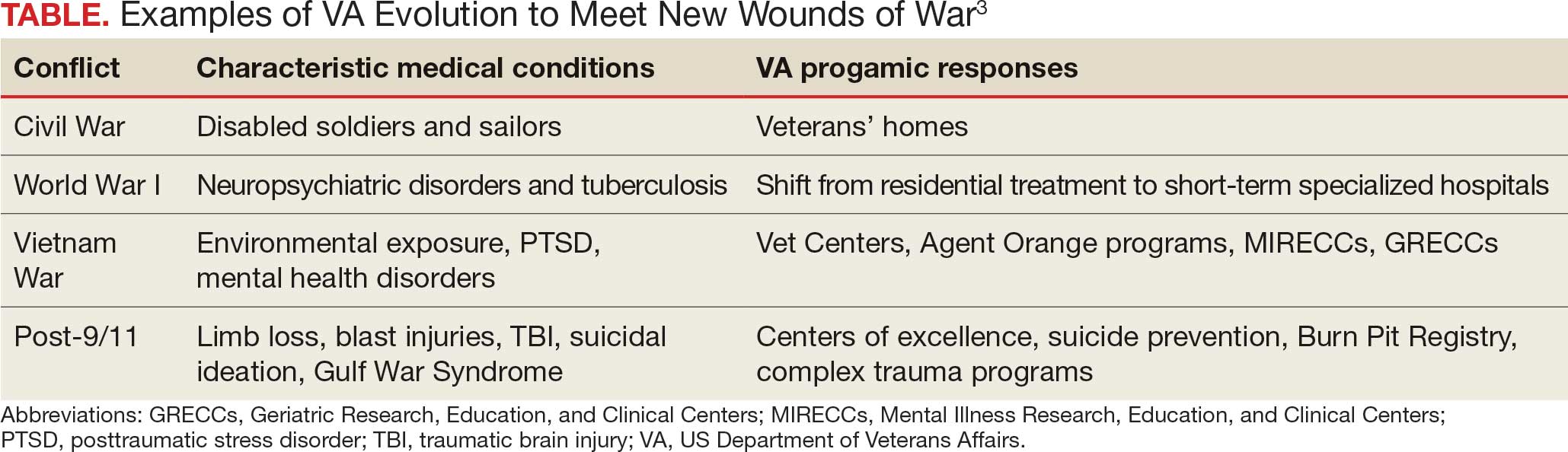

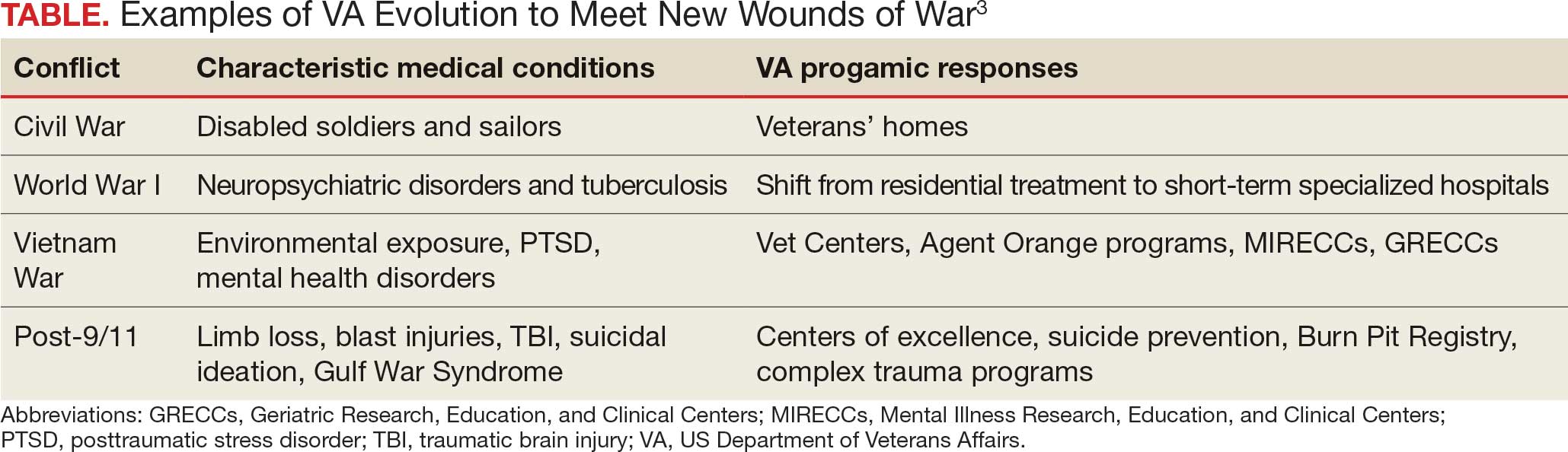

In the United States, federal practice emerged almost simultaneously with the birth of a nation. Wounded troops and families of slain soldiers required rehabilitation and support from the fledgling federal government. This began a pattern of development in which each war generated novel injuries and disorders that required the VA to evolve (Table).3

Many arguments can be marshalled to demonstrate the importance of not just ensuring VA health care survives but also has the resources needed to thrive. I will highlight what I argue are the most important justifications for its existence.

The ethical argument: President Abraham Lincoln and a long line of government officials for more than 2 centuries have called the provision of high-quality health care focused on veterans a sacred trust. Failing to fulfill that promise is a violation of the deepest principles of veracity and fidelity that those who govern owe to the citizens who selflessly sacrificed time, health, and even in some cases life, for the safety and well-being of their country.4

The quality argument: Dozens of studies have found that compared to the community, many areas of veteran medical care are just plain better. Two surveys particularly salient in the aging veteran population illustrate this growing body of positive research. The most recent and largest survey of Medicare patients found that VHA hospitals surpassed community-based hospitals on all 10 metrics.5 A retrospective cohort study of mortality compared veterans transported by ambulance to VHA or community-based hospitals. The researchers found that those taken to VHA facilities had a 30-day all cause adjustment mortality 20 times lower than those taken to civilian hospitals, especially among minoritized populations who generally have higher mortality.6

The cultural argument: Glance at almost any form of communication from veterans or about their health care and you will apprehend common cultural themes. Even when frustrated that the system has not lived up to their expectations, and perhaps because of their sense of belonging, they voice ownership of VHA as their medical home. Surveys of veteran experiences have shown many feel more comfortable receiving care in the company of comrades in arms and from health care professionals with expertise and experience with veterans’ distinctive medical problems and the military values that inform their preferences for care.7

The complexity argument: Anyone who has worked even a short time in a VHA hospital or clinic knows the patients are in general more complicated than similar patients in the community. Multiple medical, geriatric, neuropsychiatric, substance use, and social comorbidities are the expectation, not the exception, as in some civilian systems. Many of the conditions common in the VHA such as traumatic brain injury, service-connected cancers, suicidal ideation, environmental exposures, and posttraumatic stress disorder would be encountered in community health care settings. The differences between VHA and community care led the RAND Corporation to caution that “Community care providers might not be equipped to handle the needs of veterans.”8

Let me bring this 1000-foot view of the crisis facing federal practice down to the literal level of my own home. For many years I have had a wonderful mechanic who has a mobile bike service. I was talking to him as he fixed my trike. I never knew he was a Vietnam era veteran, and he didn’t realize that I was a career VA health care professional at the very VHA hospital where he received care. He spontaneously told me that, “when I first got out, the VA was awful, but now it is wonderful and they are so good to me. I would not go anywhere else.” For the many veterans of that era who would echo his sentiments, we must not allow the VA to lose all it has gained since that painful time

Another philosopher, Søren Kierkegaard, wrote that “life must be understood backwards but lived forwards.”9 Our own brief back to the future journey in this editorial has, I hope, shown that VHA medical institutions and health professionals cannot be replaced with or replicated by civilian systems and clinicians. Continued attempts to do so betray the trust and risks the health and well-being of veterans. It also would deprive the country of research, innovation, and education that make unparalleled contributions to public health. Ultimately, these efforts to diminish VHA compromise the solidarity of service members with each other and with their federal practitioners. If this trend to dismantle an organization that originated with the sole purpose of caring for veterans continues, then the public expressions of respect and gratitude will sound shallower and more tentative with each passing Veterans Day.

- Quil L. Hundreds of VA clinicians warn that cuts threaten vet’s health care. National Public Radio. October 1, 2025. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://www.npr.org/2025/10/01/nx-s1-5554394/hundreds-of-va-clinicians-warn-that-cuts-threaten-vets-health-care

- Nutton V. Ancient Medicine. 2nd ed. Routledge; 2012.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA History Summary. Updated June 13, 2025. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://department.va.gov/history/history-overview/

- Geppert CMA. Learning from history: the ethical foundation of VA health care. Fed Pract. 2016;33:6-7.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Nationwide patient survey shows VA hospitals outperform non-VA hospitals. News release. June 14, 2023. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://news.va.gov/press-room/nationwide-patient-survey-shows-va-hospitals-outperform-non-va-hospitals

- Chan DC, Danesh K, Costantini S, Card D, Taylor L, Studdert DM. Mortality among US veterans after emergency visits to Veterans Affairs and other hospitals: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2022;376:e068099. doi:10.1136/bmj-2021-068099

- Vigilante K, Batten SV, Shang Q, et al. Camaraderie among US veterans and their preferences for health care systems and practitioners. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(4):e255253. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.5253

- Rasmussen P, Farmer CM. The promise and challenges of VA community care: veterans’ issues in focus. Rand Health Q. 2023;10:9.

- Kierkegaard S. Journalen JJ:167 (1843) in: Søren Kierkegaards Skrifter. Vol 18. Copenhagen; 1997:306.

He who thus considers things in their first growth and origin ... will obtain the clearest view of them. Politics, Book I, Part II by Aristotle

Many seasoned observers of federal practice have signaled that the future of US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care is threatened as never before. Political forces and economic interests are siphoning Veterans Health Administration (VHA) capital and human resources into the community with an ineluctable push toward privatization.1

This Veterans Day, the vitality, if not the very viability of veteran health care, is in serious jeopardy, so it seems fitting to review the rationale for having institutions dedicated to the specialized medical treatment of veterans. Aristotle advises us on how to undertake this intellectual exercise in the epigraph. This column will revisit the historical origins of VA medicine to better appreciate the justification of an agency committed to this unique purpose and what may be sacrificed if it is decimated.

The provision of medical care focused on the injuries and illnesses of warriors is as old as war. The ancient Romans had among the first veterans’ hospital, named a valetudinarium. Sick and injured members of the Roman legions received state-of-the-art medical and surgical care from military doctors inside these facilities.2

In the United States, federal practice emerged almost simultaneously with the birth of a nation. Wounded troops and families of slain soldiers required rehabilitation and support from the fledgling federal government. This began a pattern of development in which each war generated novel injuries and disorders that required the VA to evolve (Table).3

Many arguments can be marshalled to demonstrate the importance of not just ensuring VA health care survives but also has the resources needed to thrive. I will highlight what I argue are the most important justifications for its existence.

The ethical argument: President Abraham Lincoln and a long line of government officials for more than 2 centuries have called the provision of high-quality health care focused on veterans a sacred trust. Failing to fulfill that promise is a violation of the deepest principles of veracity and fidelity that those who govern owe to the citizens who selflessly sacrificed time, health, and even in some cases life, for the safety and well-being of their country.4

The quality argument: Dozens of studies have found that compared to the community, many areas of veteran medical care are just plain better. Two surveys particularly salient in the aging veteran population illustrate this growing body of positive research. The most recent and largest survey of Medicare patients found that VHA hospitals surpassed community-based hospitals on all 10 metrics.5 A retrospective cohort study of mortality compared veterans transported by ambulance to VHA or community-based hospitals. The researchers found that those taken to VHA facilities had a 30-day all cause adjustment mortality 20 times lower than those taken to civilian hospitals, especially among minoritized populations who generally have higher mortality.6

The cultural argument: Glance at almost any form of communication from veterans or about their health care and you will apprehend common cultural themes. Even when frustrated that the system has not lived up to their expectations, and perhaps because of their sense of belonging, they voice ownership of VHA as their medical home. Surveys of veteran experiences have shown many feel more comfortable receiving care in the company of comrades in arms and from health care professionals with expertise and experience with veterans’ distinctive medical problems and the military values that inform their preferences for care.7

The complexity argument: Anyone who has worked even a short time in a VHA hospital or clinic knows the patients are in general more complicated than similar patients in the community. Multiple medical, geriatric, neuropsychiatric, substance use, and social comorbidities are the expectation, not the exception, as in some civilian systems. Many of the conditions common in the VHA such as traumatic brain injury, service-connected cancers, suicidal ideation, environmental exposures, and posttraumatic stress disorder would be encountered in community health care settings. The differences between VHA and community care led the RAND Corporation to caution that “Community care providers might not be equipped to handle the needs of veterans.”8

Let me bring this 1000-foot view of the crisis facing federal practice down to the literal level of my own home. For many years I have had a wonderful mechanic who has a mobile bike service. I was talking to him as he fixed my trike. I never knew he was a Vietnam era veteran, and he didn’t realize that I was a career VA health care professional at the very VHA hospital where he received care. He spontaneously told me that, “when I first got out, the VA was awful, but now it is wonderful and they are so good to me. I would not go anywhere else.” For the many veterans of that era who would echo his sentiments, we must not allow the VA to lose all it has gained since that painful time

Another philosopher, Søren Kierkegaard, wrote that “life must be understood backwards but lived forwards.”9 Our own brief back to the future journey in this editorial has, I hope, shown that VHA medical institutions and health professionals cannot be replaced with or replicated by civilian systems and clinicians. Continued attempts to do so betray the trust and risks the health and well-being of veterans. It also would deprive the country of research, innovation, and education that make unparalleled contributions to public health. Ultimately, these efforts to diminish VHA compromise the solidarity of service members with each other and with their federal practitioners. If this trend to dismantle an organization that originated with the sole purpose of caring for veterans continues, then the public expressions of respect and gratitude will sound shallower and more tentative with each passing Veterans Day.

He who thus considers things in their first growth and origin ... will obtain the clearest view of them. Politics, Book I, Part II by Aristotle

Many seasoned observers of federal practice have signaled that the future of US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care is threatened as never before. Political forces and economic interests are siphoning Veterans Health Administration (VHA) capital and human resources into the community with an ineluctable push toward privatization.1

This Veterans Day, the vitality, if not the very viability of veteran health care, is in serious jeopardy, so it seems fitting to review the rationale for having institutions dedicated to the specialized medical treatment of veterans. Aristotle advises us on how to undertake this intellectual exercise in the epigraph. This column will revisit the historical origins of VA medicine to better appreciate the justification of an agency committed to this unique purpose and what may be sacrificed if it is decimated.

The provision of medical care focused on the injuries and illnesses of warriors is as old as war. The ancient Romans had among the first veterans’ hospital, named a valetudinarium. Sick and injured members of the Roman legions received state-of-the-art medical and surgical care from military doctors inside these facilities.2

In the United States, federal practice emerged almost simultaneously with the birth of a nation. Wounded troops and families of slain soldiers required rehabilitation and support from the fledgling federal government. This began a pattern of development in which each war generated novel injuries and disorders that required the VA to evolve (Table).3

Many arguments can be marshalled to demonstrate the importance of not just ensuring VA health care survives but also has the resources needed to thrive. I will highlight what I argue are the most important justifications for its existence.

The ethical argument: President Abraham Lincoln and a long line of government officials for more than 2 centuries have called the provision of high-quality health care focused on veterans a sacred trust. Failing to fulfill that promise is a violation of the deepest principles of veracity and fidelity that those who govern owe to the citizens who selflessly sacrificed time, health, and even in some cases life, for the safety and well-being of their country.4

The quality argument: Dozens of studies have found that compared to the community, many areas of veteran medical care are just plain better. Two surveys particularly salient in the aging veteran population illustrate this growing body of positive research. The most recent and largest survey of Medicare patients found that VHA hospitals surpassed community-based hospitals on all 10 metrics.5 A retrospective cohort study of mortality compared veterans transported by ambulance to VHA or community-based hospitals. The researchers found that those taken to VHA facilities had a 30-day all cause adjustment mortality 20 times lower than those taken to civilian hospitals, especially among minoritized populations who generally have higher mortality.6

The cultural argument: Glance at almost any form of communication from veterans or about their health care and you will apprehend common cultural themes. Even when frustrated that the system has not lived up to their expectations, and perhaps because of their sense of belonging, they voice ownership of VHA as their medical home. Surveys of veteran experiences have shown many feel more comfortable receiving care in the company of comrades in arms and from health care professionals with expertise and experience with veterans’ distinctive medical problems and the military values that inform their preferences for care.7

The complexity argument: Anyone who has worked even a short time in a VHA hospital or clinic knows the patients are in general more complicated than similar patients in the community. Multiple medical, geriatric, neuropsychiatric, substance use, and social comorbidities are the expectation, not the exception, as in some civilian systems. Many of the conditions common in the VHA such as traumatic brain injury, service-connected cancers, suicidal ideation, environmental exposures, and posttraumatic stress disorder would be encountered in community health care settings. The differences between VHA and community care led the RAND Corporation to caution that “Community care providers might not be equipped to handle the needs of veterans.”8

Let me bring this 1000-foot view of the crisis facing federal practice down to the literal level of my own home. For many years I have had a wonderful mechanic who has a mobile bike service. I was talking to him as he fixed my trike. I never knew he was a Vietnam era veteran, and he didn’t realize that I was a career VA health care professional at the very VHA hospital where he received care. He spontaneously told me that, “when I first got out, the VA was awful, but now it is wonderful and they are so good to me. I would not go anywhere else.” For the many veterans of that era who would echo his sentiments, we must not allow the VA to lose all it has gained since that painful time

Another philosopher, Søren Kierkegaard, wrote that “life must be understood backwards but lived forwards.”9 Our own brief back to the future journey in this editorial has, I hope, shown that VHA medical institutions and health professionals cannot be replaced with or replicated by civilian systems and clinicians. Continued attempts to do so betray the trust and risks the health and well-being of veterans. It also would deprive the country of research, innovation, and education that make unparalleled contributions to public health. Ultimately, these efforts to diminish VHA compromise the solidarity of service members with each other and with their federal practitioners. If this trend to dismantle an organization that originated with the sole purpose of caring for veterans continues, then the public expressions of respect and gratitude will sound shallower and more tentative with each passing Veterans Day.

- Quil L. Hundreds of VA clinicians warn that cuts threaten vet’s health care. National Public Radio. October 1, 2025. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://www.npr.org/2025/10/01/nx-s1-5554394/hundreds-of-va-clinicians-warn-that-cuts-threaten-vets-health-care

- Nutton V. Ancient Medicine. 2nd ed. Routledge; 2012.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA History Summary. Updated June 13, 2025. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://department.va.gov/history/history-overview/

- Geppert CMA. Learning from history: the ethical foundation of VA health care. Fed Pract. 2016;33:6-7.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Nationwide patient survey shows VA hospitals outperform non-VA hospitals. News release. June 14, 2023. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://news.va.gov/press-room/nationwide-patient-survey-shows-va-hospitals-outperform-non-va-hospitals

- Chan DC, Danesh K, Costantini S, Card D, Taylor L, Studdert DM. Mortality among US veterans after emergency visits to Veterans Affairs and other hospitals: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2022;376:e068099. doi:10.1136/bmj-2021-068099

- Vigilante K, Batten SV, Shang Q, et al. Camaraderie among US veterans and their preferences for health care systems and practitioners. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(4):e255253. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.5253

- Rasmussen P, Farmer CM. The promise and challenges of VA community care: veterans’ issues in focus. Rand Health Q. 2023;10:9.

- Kierkegaard S. Journalen JJ:167 (1843) in: Søren Kierkegaards Skrifter. Vol 18. Copenhagen; 1997:306.

- Quil L. Hundreds of VA clinicians warn that cuts threaten vet’s health care. National Public Radio. October 1, 2025. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://www.npr.org/2025/10/01/nx-s1-5554394/hundreds-of-va-clinicians-warn-that-cuts-threaten-vets-health-care

- Nutton V. Ancient Medicine. 2nd ed. Routledge; 2012.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA History Summary. Updated June 13, 2025. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://department.va.gov/history/history-overview/

- Geppert CMA. Learning from history: the ethical foundation of VA health care. Fed Pract. 2016;33:6-7.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Nationwide patient survey shows VA hospitals outperform non-VA hospitals. News release. June 14, 2023. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://news.va.gov/press-room/nationwide-patient-survey-shows-va-hospitals-outperform-non-va-hospitals

- Chan DC, Danesh K, Costantini S, Card D, Taylor L, Studdert DM. Mortality among US veterans after emergency visits to Veterans Affairs and other hospitals: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2022;376:e068099. doi:10.1136/bmj-2021-068099

- Vigilante K, Batten SV, Shang Q, et al. Camaraderie among US veterans and their preferences for health care systems and practitioners. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(4):e255253. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.5253

- Rasmussen P, Farmer CM. The promise and challenges of VA community care: veterans’ issues in focus. Rand Health Q. 2023;10:9.

- Kierkegaard S. Journalen JJ:167 (1843) in: Søren Kierkegaards Skrifter. Vol 18. Copenhagen; 1997:306.

The Once and Future Veterans Health Administration

The Once and Future Veterans Health Administration

Special Report II: Tackling Burnout

Last month, we introduced the epidemic of burnout and the adverse consequences for both our vascular surgery patients and ourselves. Today we will outline a framework for addressing these issues. The foundation of this framework is informed by the social and neurosciences.

From the perspective of the social scientist: Christina Maslach, the originator of the widely used Maslach Burnout Inventory, theorized that burnout arises from a chronic mismatch between people and their work setting in some or all of the following domains: Workload (too much, wrong kind); control (lack of autonomy, or insufficient control over resources); reward (insufficient financial or social rewards commensurate with achievements); community (loss of positive connection with others); fairness (lack of perceived fairness, inequity of work, pay, or promotion); and values (conflict of personal and organizational values). The reality of practicing medicine in today’s business milieu – of achieving service efficiencies by meeting performance targets – brings many of these mismatches into sharp focus.

From the perspective of the neuroscientist: Recent advances, including functional MRI, have demonstrated that the human brain is hard wired for compassion. Compassion is the deep feeling that arises when confronted with another’s suffering, coupled with a strong desire to alleviate that suffering. There are at least two neural pathways: one activated during empathy, having us experience another’s pain; and the other activated during compassion, resulting in our sense of reward. Thus, burnout is thought to occur when you know what your patient needs but you are unable to deliver it. Compassionate medical care is purposeful work, which promotes a sense of reward and mitigates burnout.

Because burnout affects all caregivers (anyone who touches the patient), a successful program addressing workforce well-being must be comprehensive and organization wide, similar to successful patient safety, CPI [continuous process improvement] and LEAN [Six Sigma] initiatives.

There are no shortcuts. Creating a culture of compassionate, collaborative care requires an understanding of the interrelationships between the individual provider, the unit or team, and organizational leadership.

1) The individual provider: There is evidence to support the use of programs that build personal resilience. A recently published meta-analysis by West and colleagues concluded that while no specific physician burnout intervention has been shown to be better than other types of interventions, mindfulness, stress management, and small-group discussions can be effective approaches to reducing burnout scores. Strategies to build individual resilience, such as mindfulness and meditation, are easy to teach but place the burden for success on the individual. No amount of resilience can withstand an unsupportive or toxic workplace environment, so both individual and organizational strategies in combination are necessary.

2) The unit or team: Scheduling time for open and honest discussion of social and emotional issues that arise in caring for patients helps nourish caregiver to caregiver compassion. The Schwartz Center for Compassionate Healthcare is a national nonprofit leading the movement to bring compassion to every patient-caregiver interaction. More than 425 health care organization are Schwartz Center members and conduct Schwartz Rounds™ to bring doctors, nurses, and other caregivers together to discuss the human side of health care. (www.theschwartzcenter.org). Team member to team member support is essential for navigating the stressors of practice. With having lunch in front of your computer being the norm, and the disappearance of traditional spaces for colleagues to connect (for example, nurses’ lounge, physician dining rooms), the opportunity for caregivers to have a safe place to escape, a place to have their own humanity reaffirmed, a place to offer support to their peers, has been eliminated.

3) Organizational Leadership: Making compassion a core value, articulating it, and establishing metrics whereby it can be measured, is a good start. The barriers to a culture of compassion are related to our systems of care. There are burgeoning administrative and documentation tasks to be performed, and productivity expectations that turn our clinics and hospitals into assembly lines. No, we cannot expect the EMR [electronic medical records] to be eliminated, but workforce well-being cannot be sustainable in the context of inadequate resources. A culture of compassionate collaborative care requires programs and policies that are implemented by the organization itself. Examples of organization-wide initiatives that support workforce well-being and provider engagement include: screening for caregiver burnout, establishing policies for managing adverse events with an eye toward the second victim, and most importantly, supporting systems that preserve work control autonomy of physicians and nurses in clinical settings. The business sector has long recognized that workplace stress is a function of how demanding a person’s job is and how much control that person has over his or her responsibilities. The business community has also recognized that the experience of the worker (provider) drives the experience of the customer (patient). In a study of hospital compassionate practices and HCAHPS [the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems], McClelland and Vogus reported that how well a hospital compassionately supports it employees and rewards compassionate acts is significantly and positively is associated with that hospital’s ratings and likelihood of patients recommending it.

How does the Society of Vascular Surgery, or any professional medical/nursing society for that matter, fit into this model?

We propose that the SVS find ways to empower their members to be agents for culture change within their own health care organizations. How might this be done:

- Teach organizational leadership skills, starting with the SVS Board of Directors, the presidential line, and the chairs of committees. Offer leadership courses at the Annual Meeting.

- Develop a community of caregivers committed to creating a compassionate collaborative culture. The SVS is a founding member of the Schwartz Center Healthcare Society Leadership Council, and you, as members of the SVS benefit from reduced registration at the Annual Compassion in Action Healthcare Conference, June 24-27, 2017 in Boston. (http://compassioninactionconference.org) This conference is designed to be highly experiential, using a hands-on “how to do it” model.

- The SVS should make improving the overall wellness of its members a specific goal and find specific metrics to monitor our progress towards this goal. Members can be provided with the tools to identify, monitor, and measure burnout and compassion. Each committee and council of the SVS can reexamine their objectives through the lens of reducing burnout and improving the wellness of vascular surgeons.

- Provide members with evidence-based programs that build personal resilience. This will not be a successful initiative unless our surgeons recognize and acknowledge the symptoms of burnout, and are willing to admit vulnerability. Without doing so, it is difficult to reach out for help.

- Redesign postgraduate resident and fellowship education. Standardizing clinical care may reduce variation and promote efficiency. However, when processes such as time-limited appointment scheduling, EMR templates, and protocols that drive physician-patient interactions are embedded in Resident and Fellowship education, the result may well be inflexibility in practice, reduced face time with patients, and interactions that lack compassion; all leading to burnout. Graduate Medical Education leaders must develop programs that support the learner’s ability to connect with patients and families, cultivate and role-model skills and behaviors that strengthen compassionate interactions, and strive to develop clinical practice models that increase Resident and Fellow work control autonomy.

The SVS should work proactively to optimize workload, fairness, and reward on a larger scale for its members as it relates to the EMR, reimbursement, and systems coverage. While we may be relatively small in size, as leaders, we are perfectly poised to address these larger, global issues. Perhaps working within the current system (i.e., PAC and APM task force) and considering innovative solutions at a national leadership scale, the SVS can direct real change!

Changing culture is not easy, nor quick, nor does it have an easy-to-follow blueprint. The first step is recognizing the need. The second is taking a leadership role. The third is thinking deeply about implementation.

*The authors extend their thanks and appreciation for the guidance, resources and support of Michael Goldberg, MD, scholar in residence, Schwartz Center for Compassionate Care, Boston and clinical professor of orthopedics at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

REFERENCES

1. J Managerial Psychol. (2007) 22:309-28

2. Annu Rev Neurosci. (2012) 35:1-23

3. Medicine. (2016) 44:583-5

4. J Health Organization Manag. (2015) 29:973-87

5. De Zulueta P Developing compassionate leadership in health care: an integrative review. J Healthcare Leadership. (2016) 8:1-10

6. Dolan ED, Morh D, Lempa M et al. Using a single item to measure burnout in primary care staff: A psychometry evaluation. J Gen Intern Med. (2015) 30:582-7

7. Karasek RA Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job design. Administrative Sciences Quarterly (1979) 24: 285-308

8. Lee VS, Miller T, Daniels C, et al. Creating the exceptional patient experience in one academic health system. Acad Med. (2016) 91:338-44

9. Linzer M, Levine R, Meltzer D, et al. 10 bold steps to prevent burnout in general internal medicine. J Gen Intern Med. (2013) 29:18-20

10. Lown BA, Manning CF The Schwartz Center Rounds: Evaluation of an interdisciplinary approach to enhancing patient-centered communication, teamwork, and provider support. Acad Med. (2010) 85:1073-81

11. Lown BA, Muncer SJ, Chadwick R Can compassionate healthcare be measured? The Schwartz Center Compassionate Care Scale. Patient Education and Counseling (2015) 98:1005-10

12. Lown BA, McIntosh S, Gaines ME, et. al. Integrating compassionate collaborative care (“the Triple C”) into health professional education to advance the triple aim of health care. Acad Med (2016) 91:1-7

13. Lown BA A social neuroscience-informed model for teaching and practicing compassion in health care. Medical Education (2016) 50: 332-342

14. Maslach C, Schaufeli WG, Leiter MP Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol (2001) 52:397-422

15. McClelland LE, Vogus TJ Compassion practices and HCAHPS: Does rewarding and supporting workplace compassion influence patient perceptions? HSR: Health Serv Res. (2014) 49:1670-83

16. Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH Executive leadership and physician well-being: Nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. (2016) 6:1-18

17. Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP Addressing physician burnout: the way forward. JAMA (2017) 317:901-2

18. Singer T, Klimecki OM Empathy and compassion Curr Biol. (2014) 24: R875-8

19. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Satele DV et. al. Concurrent validity of single-item measures of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization in burnout assessment. J Gen Intern Med. (2012) 27:1445-52

20. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, et al. Interventions to address and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. (2016) 388:2272-81

21. Wuest TK, Goldberg MJ, Kelly JD Clinical faceoff: Physician burnout-Fact, fantasy, or the fourth component of the triple aim? Clin Orthop Relat Res. (2016) doi: 10.1007/5-11999-016-5193-5

Last month, we introduced the epidemic of burnout and the adverse consequences for both our vascular surgery patients and ourselves. Today we will outline a framework for addressing these issues. The foundation of this framework is informed by the social and neurosciences.

From the perspective of the social scientist: Christina Maslach, the originator of the widely used Maslach Burnout Inventory, theorized that burnout arises from a chronic mismatch between people and their work setting in some or all of the following domains: Workload (too much, wrong kind); control (lack of autonomy, or insufficient control over resources); reward (insufficient financial or social rewards commensurate with achievements); community (loss of positive connection with others); fairness (lack of perceived fairness, inequity of work, pay, or promotion); and values (conflict of personal and organizational values). The reality of practicing medicine in today’s business milieu – of achieving service efficiencies by meeting performance targets – brings many of these mismatches into sharp focus.

From the perspective of the neuroscientist: Recent advances, including functional MRI, have demonstrated that the human brain is hard wired for compassion. Compassion is the deep feeling that arises when confronted with another’s suffering, coupled with a strong desire to alleviate that suffering. There are at least two neural pathways: one activated during empathy, having us experience another’s pain; and the other activated during compassion, resulting in our sense of reward. Thus, burnout is thought to occur when you know what your patient needs but you are unable to deliver it. Compassionate medical care is purposeful work, which promotes a sense of reward and mitigates burnout.

Because burnout affects all caregivers (anyone who touches the patient), a successful program addressing workforce well-being must be comprehensive and organization wide, similar to successful patient safety, CPI [continuous process improvement] and LEAN [Six Sigma] initiatives.

There are no shortcuts. Creating a culture of compassionate, collaborative care requires an understanding of the interrelationships between the individual provider, the unit or team, and organizational leadership.

1) The individual provider: There is evidence to support the use of programs that build personal resilience. A recently published meta-analysis by West and colleagues concluded that while no specific physician burnout intervention has been shown to be better than other types of interventions, mindfulness, stress management, and small-group discussions can be effective approaches to reducing burnout scores. Strategies to build individual resilience, such as mindfulness and meditation, are easy to teach but place the burden for success on the individual. No amount of resilience can withstand an unsupportive or toxic workplace environment, so both individual and organizational strategies in combination are necessary.

2) The unit or team: Scheduling time for open and honest discussion of social and emotional issues that arise in caring for patients helps nourish caregiver to caregiver compassion. The Schwartz Center for Compassionate Healthcare is a national nonprofit leading the movement to bring compassion to every patient-caregiver interaction. More than 425 health care organization are Schwartz Center members and conduct Schwartz Rounds™ to bring doctors, nurses, and other caregivers together to discuss the human side of health care. (www.theschwartzcenter.org). Team member to team member support is essential for navigating the stressors of practice. With having lunch in front of your computer being the norm, and the disappearance of traditional spaces for colleagues to connect (for example, nurses’ lounge, physician dining rooms), the opportunity for caregivers to have a safe place to escape, a place to have their own humanity reaffirmed, a place to offer support to their peers, has been eliminated.

3) Organizational Leadership: Making compassion a core value, articulating it, and establishing metrics whereby it can be measured, is a good start. The barriers to a culture of compassion are related to our systems of care. There are burgeoning administrative and documentation tasks to be performed, and productivity expectations that turn our clinics and hospitals into assembly lines. No, we cannot expect the EMR [electronic medical records] to be eliminated, but workforce well-being cannot be sustainable in the context of inadequate resources. A culture of compassionate collaborative care requires programs and policies that are implemented by the organization itself. Examples of organization-wide initiatives that support workforce well-being and provider engagement include: screening for caregiver burnout, establishing policies for managing adverse events with an eye toward the second victim, and most importantly, supporting systems that preserve work control autonomy of physicians and nurses in clinical settings. The business sector has long recognized that workplace stress is a function of how demanding a person’s job is and how much control that person has over his or her responsibilities. The business community has also recognized that the experience of the worker (provider) drives the experience of the customer (patient). In a study of hospital compassionate practices and HCAHPS [the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems], McClelland and Vogus reported that how well a hospital compassionately supports it employees and rewards compassionate acts is significantly and positively is associated with that hospital’s ratings and likelihood of patients recommending it.

How does the Society of Vascular Surgery, or any professional medical/nursing society for that matter, fit into this model?

We propose that the SVS find ways to empower their members to be agents for culture change within their own health care organizations. How might this be done:

- Teach organizational leadership skills, starting with the SVS Board of Directors, the presidential line, and the chairs of committees. Offer leadership courses at the Annual Meeting.

- Develop a community of caregivers committed to creating a compassionate collaborative culture. The SVS is a founding member of the Schwartz Center Healthcare Society Leadership Council, and you, as members of the SVS benefit from reduced registration at the Annual Compassion in Action Healthcare Conference, June 24-27, 2017 in Boston. (http://compassioninactionconference.org) This conference is designed to be highly experiential, using a hands-on “how to do it” model.

- The SVS should make improving the overall wellness of its members a specific goal and find specific metrics to monitor our progress towards this goal. Members can be provided with the tools to identify, monitor, and measure burnout and compassion. Each committee and council of the SVS can reexamine their objectives through the lens of reducing burnout and improving the wellness of vascular surgeons.

- Provide members with evidence-based programs that build personal resilience. This will not be a successful initiative unless our surgeons recognize and acknowledge the symptoms of burnout, and are willing to admit vulnerability. Without doing so, it is difficult to reach out for help.

- Redesign postgraduate resident and fellowship education. Standardizing clinical care may reduce variation and promote efficiency. However, when processes such as time-limited appointment scheduling, EMR templates, and protocols that drive physician-patient interactions are embedded in Resident and Fellowship education, the result may well be inflexibility in practice, reduced face time with patients, and interactions that lack compassion; all leading to burnout. Graduate Medical Education leaders must develop programs that support the learner’s ability to connect with patients and families, cultivate and role-model skills and behaviors that strengthen compassionate interactions, and strive to develop clinical practice models that increase Resident and Fellow work control autonomy.

The SVS should work proactively to optimize workload, fairness, and reward on a larger scale for its members as it relates to the EMR, reimbursement, and systems coverage. While we may be relatively small in size, as leaders, we are perfectly poised to address these larger, global issues. Perhaps working within the current system (i.e., PAC and APM task force) and considering innovative solutions at a national leadership scale, the SVS can direct real change!

Changing culture is not easy, nor quick, nor does it have an easy-to-follow blueprint. The first step is recognizing the need. The second is taking a leadership role. The third is thinking deeply about implementation.

*The authors extend their thanks and appreciation for the guidance, resources and support of Michael Goldberg, MD, scholar in residence, Schwartz Center for Compassionate Care, Boston and clinical professor of orthopedics at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

REFERENCES

1. J Managerial Psychol. (2007) 22:309-28

2. Annu Rev Neurosci. (2012) 35:1-23

3. Medicine. (2016) 44:583-5

4. J Health Organization Manag. (2015) 29:973-87

5. De Zulueta P Developing compassionate leadership in health care: an integrative review. J Healthcare Leadership. (2016) 8:1-10

6. Dolan ED, Morh D, Lempa M et al. Using a single item to measure burnout in primary care staff: A psychometry evaluation. J Gen Intern Med. (2015) 30:582-7

7. Karasek RA Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job design. Administrative Sciences Quarterly (1979) 24: 285-308

8. Lee VS, Miller T, Daniels C, et al. Creating the exceptional patient experience in one academic health system. Acad Med. (2016) 91:338-44

9. Linzer M, Levine R, Meltzer D, et al. 10 bold steps to prevent burnout in general internal medicine. J Gen Intern Med. (2013) 29:18-20

10. Lown BA, Manning CF The Schwartz Center Rounds: Evaluation of an interdisciplinary approach to enhancing patient-centered communication, teamwork, and provider support. Acad Med. (2010) 85:1073-81

11. Lown BA, Muncer SJ, Chadwick R Can compassionate healthcare be measured? The Schwartz Center Compassionate Care Scale. Patient Education and Counseling (2015) 98:1005-10

12. Lown BA, McIntosh S, Gaines ME, et. al. Integrating compassionate collaborative care (“the Triple C”) into health professional education to advance the triple aim of health care. Acad Med (2016) 91:1-7

13. Lown BA A social neuroscience-informed model for teaching and practicing compassion in health care. Medical Education (2016) 50: 332-342

14. Maslach C, Schaufeli WG, Leiter MP Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol (2001) 52:397-422

15. McClelland LE, Vogus TJ Compassion practices and HCAHPS: Does rewarding and supporting workplace compassion influence patient perceptions? HSR: Health Serv Res. (2014) 49:1670-83

16. Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH Executive leadership and physician well-being: Nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. (2016) 6:1-18

17. Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP Addressing physician burnout: the way forward. JAMA (2017) 317:901-2

18. Singer T, Klimecki OM Empathy and compassion Curr Biol. (2014) 24: R875-8

19. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Satele DV et. al. Concurrent validity of single-item measures of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization in burnout assessment. J Gen Intern Med. (2012) 27:1445-52

20. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, et al. Interventions to address and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. (2016) 388:2272-81

21. Wuest TK, Goldberg MJ, Kelly JD Clinical faceoff: Physician burnout-Fact, fantasy, or the fourth component of the triple aim? Clin Orthop Relat Res. (2016) doi: 10.1007/5-11999-016-5193-5

Last month, we introduced the epidemic of burnout and the adverse consequences for both our vascular surgery patients and ourselves. Today we will outline a framework for addressing these issues. The foundation of this framework is informed by the social and neurosciences.

From the perspective of the social scientist: Christina Maslach, the originator of the widely used Maslach Burnout Inventory, theorized that burnout arises from a chronic mismatch between people and their work setting in some or all of the following domains: Workload (too much, wrong kind); control (lack of autonomy, or insufficient control over resources); reward (insufficient financial or social rewards commensurate with achievements); community (loss of positive connection with others); fairness (lack of perceived fairness, inequity of work, pay, or promotion); and values (conflict of personal and organizational values). The reality of practicing medicine in today’s business milieu – of achieving service efficiencies by meeting performance targets – brings many of these mismatches into sharp focus.

From the perspective of the neuroscientist: Recent advances, including functional MRI, have demonstrated that the human brain is hard wired for compassion. Compassion is the deep feeling that arises when confronted with another’s suffering, coupled with a strong desire to alleviate that suffering. There are at least two neural pathways: one activated during empathy, having us experience another’s pain; and the other activated during compassion, resulting in our sense of reward. Thus, burnout is thought to occur when you know what your patient needs but you are unable to deliver it. Compassionate medical care is purposeful work, which promotes a sense of reward and mitigates burnout.

Because burnout affects all caregivers (anyone who touches the patient), a successful program addressing workforce well-being must be comprehensive and organization wide, similar to successful patient safety, CPI [continuous process improvement] and LEAN [Six Sigma] initiatives.

There are no shortcuts. Creating a culture of compassionate, collaborative care requires an understanding of the interrelationships between the individual provider, the unit or team, and organizational leadership.

1) The individual provider: There is evidence to support the use of programs that build personal resilience. A recently published meta-analysis by West and colleagues concluded that while no specific physician burnout intervention has been shown to be better than other types of interventions, mindfulness, stress management, and small-group discussions can be effective approaches to reducing burnout scores. Strategies to build individual resilience, such as mindfulness and meditation, are easy to teach but place the burden for success on the individual. No amount of resilience can withstand an unsupportive or toxic workplace environment, so both individual and organizational strategies in combination are necessary.

2) The unit or team: Scheduling time for open and honest discussion of social and emotional issues that arise in caring for patients helps nourish caregiver to caregiver compassion. The Schwartz Center for Compassionate Healthcare is a national nonprofit leading the movement to bring compassion to every patient-caregiver interaction. More than 425 health care organization are Schwartz Center members and conduct Schwartz Rounds™ to bring doctors, nurses, and other caregivers together to discuss the human side of health care. (www.theschwartzcenter.org). Team member to team member support is essential for navigating the stressors of practice. With having lunch in front of your computer being the norm, and the disappearance of traditional spaces for colleagues to connect (for example, nurses’ lounge, physician dining rooms), the opportunity for caregivers to have a safe place to escape, a place to have their own humanity reaffirmed, a place to offer support to their peers, has been eliminated.

3) Organizational Leadership: Making compassion a core value, articulating it, and establishing metrics whereby it can be measured, is a good start. The barriers to a culture of compassion are related to our systems of care. There are burgeoning administrative and documentation tasks to be performed, and productivity expectations that turn our clinics and hospitals into assembly lines. No, we cannot expect the EMR [electronic medical records] to be eliminated, but workforce well-being cannot be sustainable in the context of inadequate resources. A culture of compassionate collaborative care requires programs and policies that are implemented by the organization itself. Examples of organization-wide initiatives that support workforce well-being and provider engagement include: screening for caregiver burnout, establishing policies for managing adverse events with an eye toward the second victim, and most importantly, supporting systems that preserve work control autonomy of physicians and nurses in clinical settings. The business sector has long recognized that workplace stress is a function of how demanding a person’s job is and how much control that person has over his or her responsibilities. The business community has also recognized that the experience of the worker (provider) drives the experience of the customer (patient). In a study of hospital compassionate practices and HCAHPS [the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems], McClelland and Vogus reported that how well a hospital compassionately supports it employees and rewards compassionate acts is significantly and positively is associated with that hospital’s ratings and likelihood of patients recommending it.

How does the Society of Vascular Surgery, or any professional medical/nursing society for that matter, fit into this model?

We propose that the SVS find ways to empower their members to be agents for culture change within their own health care organizations. How might this be done:

- Teach organizational leadership skills, starting with the SVS Board of Directors, the presidential line, and the chairs of committees. Offer leadership courses at the Annual Meeting.

- Develop a community of caregivers committed to creating a compassionate collaborative culture. The SVS is a founding member of the Schwartz Center Healthcare Society Leadership Council, and you, as members of the SVS benefit from reduced registration at the Annual Compassion in Action Healthcare Conference, June 24-27, 2017 in Boston. (http://compassioninactionconference.org) This conference is designed to be highly experiential, using a hands-on “how to do it” model.

- The SVS should make improving the overall wellness of its members a specific goal and find specific metrics to monitor our progress towards this goal. Members can be provided with the tools to identify, monitor, and measure burnout and compassion. Each committee and council of the SVS can reexamine their objectives through the lens of reducing burnout and improving the wellness of vascular surgeons.

- Provide members with evidence-based programs that build personal resilience. This will not be a successful initiative unless our surgeons recognize and acknowledge the symptoms of burnout, and are willing to admit vulnerability. Without doing so, it is difficult to reach out for help.

- Redesign postgraduate resident and fellowship education. Standardizing clinical care may reduce variation and promote efficiency. However, when processes such as time-limited appointment scheduling, EMR templates, and protocols that drive physician-patient interactions are embedded in Resident and Fellowship education, the result may well be inflexibility in practice, reduced face time with patients, and interactions that lack compassion; all leading to burnout. Graduate Medical Education leaders must develop programs that support the learner’s ability to connect with patients and families, cultivate and role-model skills and behaviors that strengthen compassionate interactions, and strive to develop clinical practice models that increase Resident and Fellow work control autonomy.

The SVS should work proactively to optimize workload, fairness, and reward on a larger scale for its members as it relates to the EMR, reimbursement, and systems coverage. While we may be relatively small in size, as leaders, we are perfectly poised to address these larger, global issues. Perhaps working within the current system (i.e., PAC and APM task force) and considering innovative solutions at a national leadership scale, the SVS can direct real change!

Changing culture is not easy, nor quick, nor does it have an easy-to-follow blueprint. The first step is recognizing the need. The second is taking a leadership role. The third is thinking deeply about implementation.

*The authors extend their thanks and appreciation for the guidance, resources and support of Michael Goldberg, MD, scholar in residence, Schwartz Center for Compassionate Care, Boston and clinical professor of orthopedics at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

REFERENCES

1. J Managerial Psychol. (2007) 22:309-28

2. Annu Rev Neurosci. (2012) 35:1-23

3. Medicine. (2016) 44:583-5

4. J Health Organization Manag. (2015) 29:973-87

5. De Zulueta P Developing compassionate leadership in health care: an integrative review. J Healthcare Leadership. (2016) 8:1-10

6. Dolan ED, Morh D, Lempa M et al. Using a single item to measure burnout in primary care staff: A psychometry evaluation. J Gen Intern Med. (2015) 30:582-7

7. Karasek RA Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job design. Administrative Sciences Quarterly (1979) 24: 285-308

8. Lee VS, Miller T, Daniels C, et al. Creating the exceptional patient experience in one academic health system. Acad Med. (2016) 91:338-44

9. Linzer M, Levine R, Meltzer D, et al. 10 bold steps to prevent burnout in general internal medicine. J Gen Intern Med. (2013) 29:18-20

10. Lown BA, Manning CF The Schwartz Center Rounds: Evaluation of an interdisciplinary approach to enhancing patient-centered communication, teamwork, and provider support. Acad Med. (2010) 85:1073-81

11. Lown BA, Muncer SJ, Chadwick R Can compassionate healthcare be measured? The Schwartz Center Compassionate Care Scale. Patient Education and Counseling (2015) 98:1005-10

12. Lown BA, McIntosh S, Gaines ME, et. al. Integrating compassionate collaborative care (“the Triple C”) into health professional education to advance the triple aim of health care. Acad Med (2016) 91:1-7

13. Lown BA A social neuroscience-informed model for teaching and practicing compassion in health care. Medical Education (2016) 50: 332-342

14. Maslach C, Schaufeli WG, Leiter MP Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol (2001) 52:397-422

15. McClelland LE, Vogus TJ Compassion practices and HCAHPS: Does rewarding and supporting workplace compassion influence patient perceptions? HSR: Health Serv Res. (2014) 49:1670-83

16. Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH Executive leadership and physician well-being: Nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. (2016) 6:1-18

17. Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP Addressing physician burnout: the way forward. JAMA (2017) 317:901-2

18. Singer T, Klimecki OM Empathy and compassion Curr Biol. (2014) 24: R875-8

19. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Satele DV et. al. Concurrent validity of single-item measures of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization in burnout assessment. J Gen Intern Med. (2012) 27:1445-52

20. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, et al. Interventions to address and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. (2016) 388:2272-81

21. Wuest TK, Goldberg MJ, Kelly JD Clinical faceoff: Physician burnout-Fact, fantasy, or the fourth component of the triple aim? Clin Orthop Relat Res. (2016) doi: 10.1007/5-11999-016-5193-5

Transplantation palliative care: The time is ripe

Over 10 years ago, a challenge was made in a surgical publication for increased collaboration between the fields of transplantation and palliative care.1

Since that time not much progress has been made bringing these fields together in a consistent way that would mutually benefit patients and the specialties. However, other progress has been made, particularly in the field of palliative care, which could brighten the prospects and broaden the opportunities to accomplish collaboration between palliative care and transplantation.

Growth of palliative services

During the past decade there has been a robust proliferation of hospital-based palliative care programs in the United States. In all, 67% of U.S. hospitals with 50 or more beds report palliative care teams, up from 63% in 2011 and 53% in 2008.

Only a decade ago, critical care and palliative care were generally considered mutually exclusive. Evidence is trickling in to suggest that this is no longer the case. Although palliative care was not an integral part of critical care at that time, patients, families, and even practitioners began to demand these services. Cook and Rocker have eloquently advocated the rightful place of palliative care in the ICU.2

Studies in recent years have shown that the integration of palliative care into critical care decreases in length of ICU and hospital stay, decreases costs, enhances patient/family satisfaction, and promotes a more rapid consensus about goals of care, without increasing mortality. The ICU experience to date could be considered a reassuring precedent for transplantation palliative care.

Integration of palliative care with transplantation

Early palliative care intervention has been shown to improve symptom burden and depression scores in end-stage liver disease patients awaiting transplant. In addition, early palliative care consultation in conjunction with cancer treatment has been associated with increased survival in non–small-cell lung cancer patients. It has been demonstrated that early integration of palliative care in the surgical ICU alongside disease-directed curative care can be accomplished without change in mortality, while improving end-of-life practice in liver transplant patients.3

What palliative care can do for transplant patients