User login

Repair of a Large Full-Thickness Conchal Bowl Defect

Repair of a Large Full-Thickness Conchal Bowl Defect

Practice Gap

Large full-thickness conchal bowl defects often pose a reconstructive challenge. Maintaining the shape and structural integrity of the concha is fundamental for optimal cosmetic and functional outcomes. Prior reports have suggested wedge excisions, composite grafts, interpolation flaps with or without cartilage struts, and hinge flaps as possible options for reconstruction.1-3 However, patients with large defects who prefer single-stage reconstruction procedures present a unique challenge. Herein, we describe a single-stage full-thickness hinge flap technique for a large conchal bowl defect.

The Technique

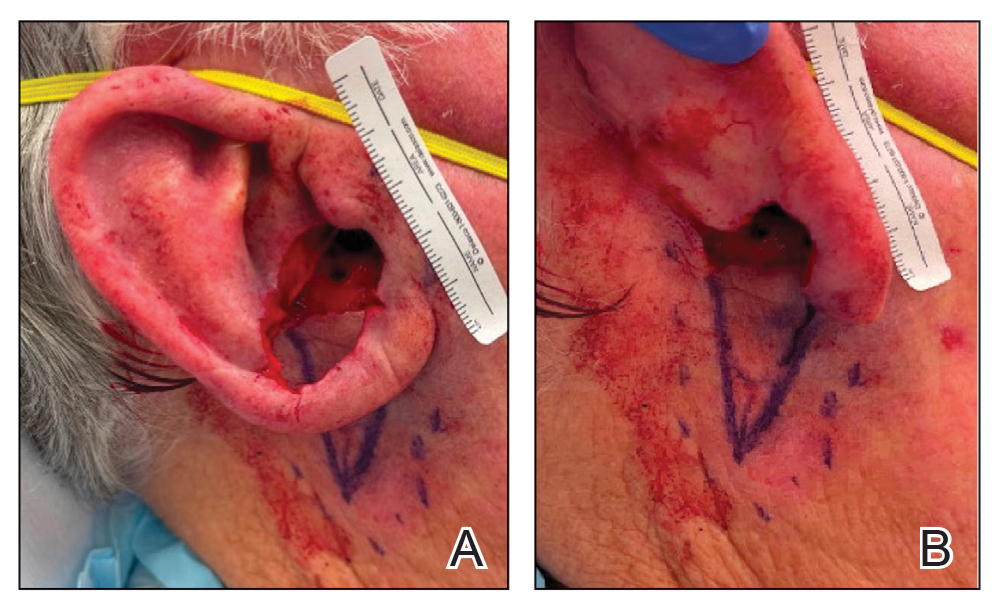

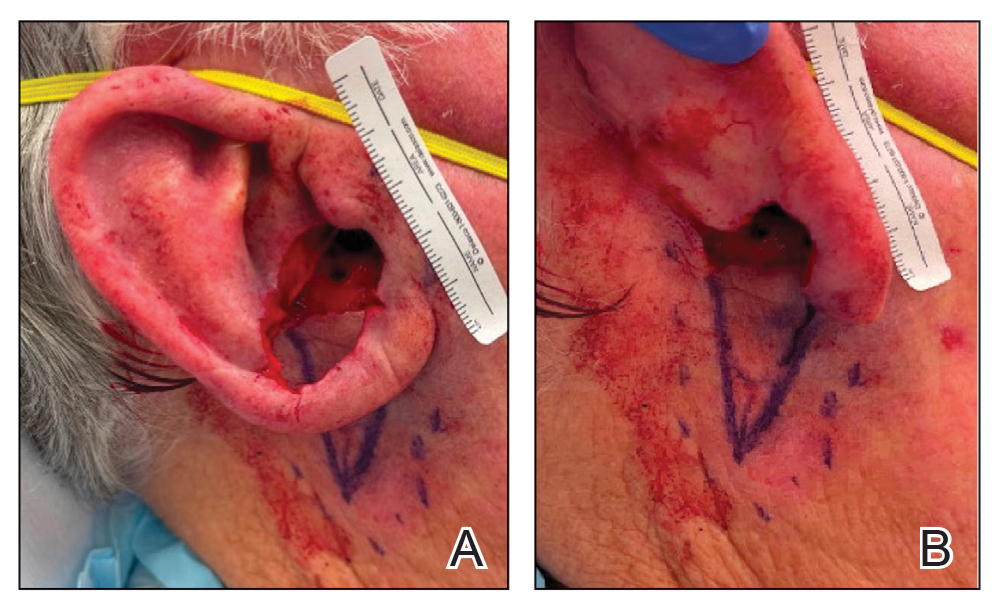

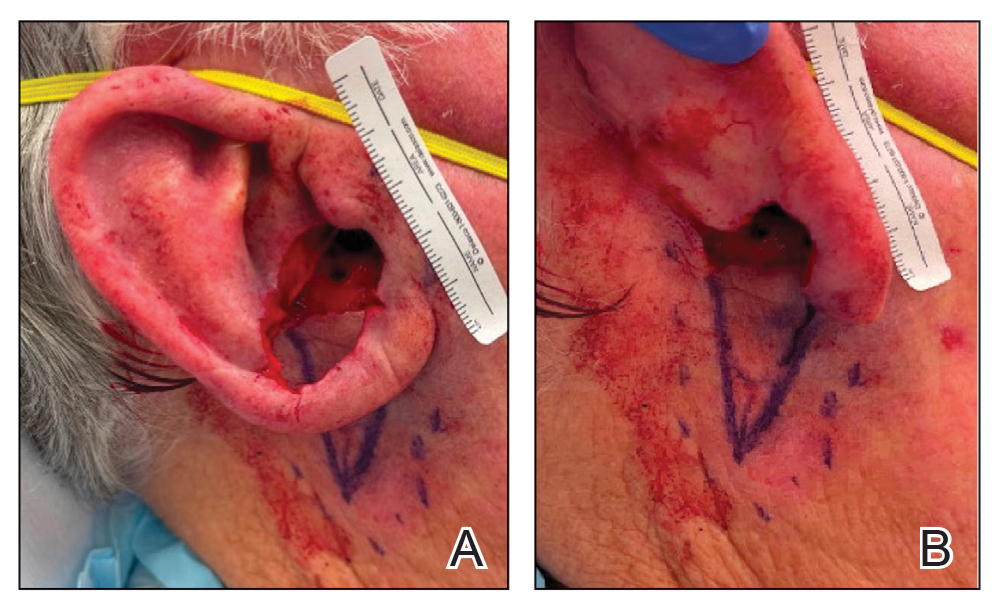

A 77-year-old man was referred to our dermatology clinic by an outside dermatologist for Mohs micrographic surgery of a biopsy-proven cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma on the right conchal bowl measuring 1.1×2.1 cm and extending to the edge of the external auditory canal (EAC). The excision was performed that same day and was completed in 2 stages, achieving negative margins and resulting in a full-thickness defect measuring 2.0×3.6 cm that included the posterior auricular sulcus, cavum, antitragus, and proximal EAC (Figure 1). The patient requested a single-stage procedure but emphasized that his main priority was an optimal cosmetic outcome.

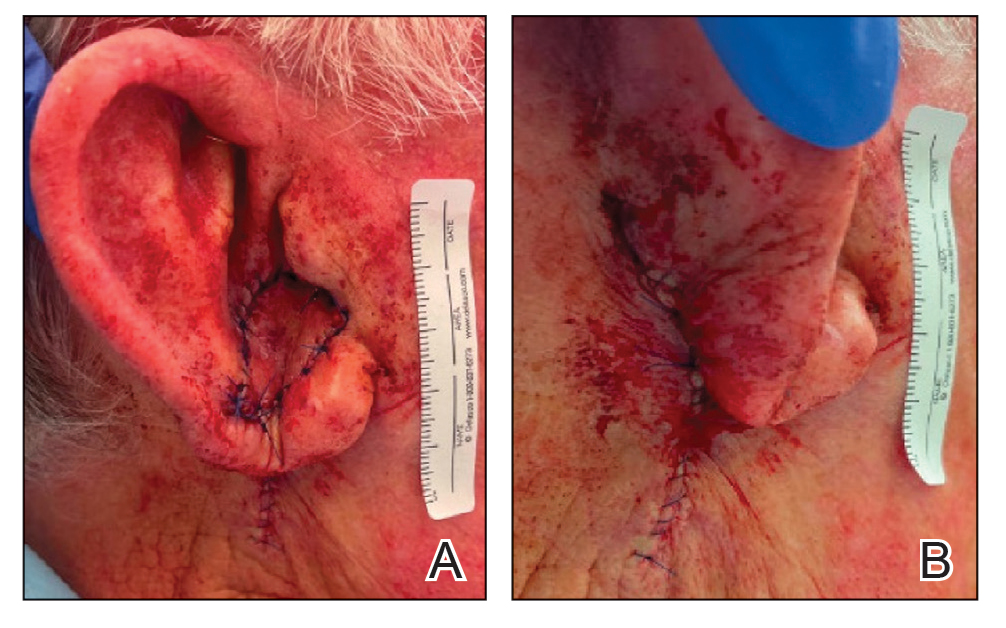

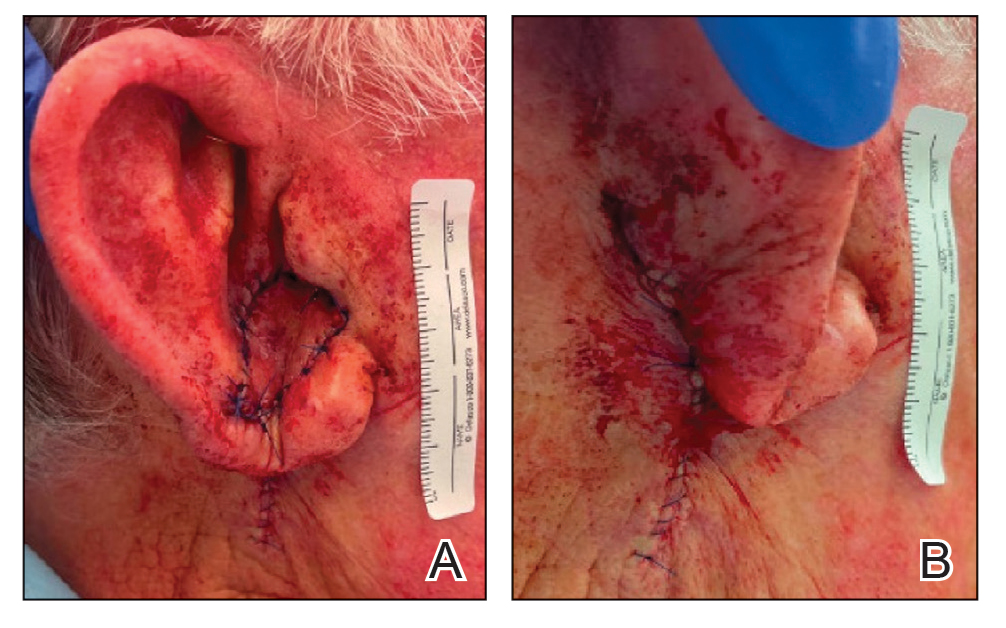

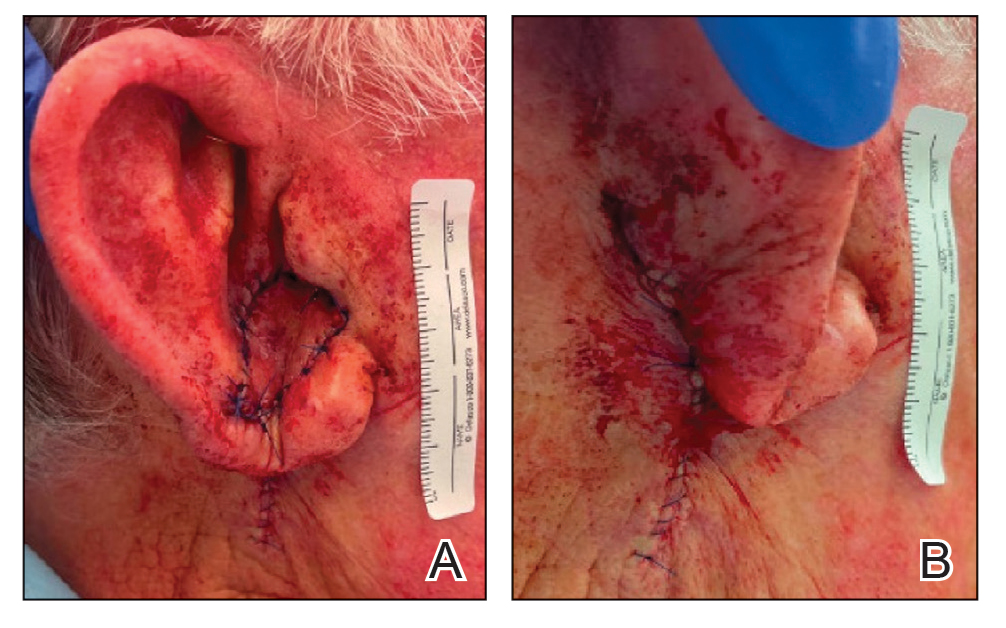

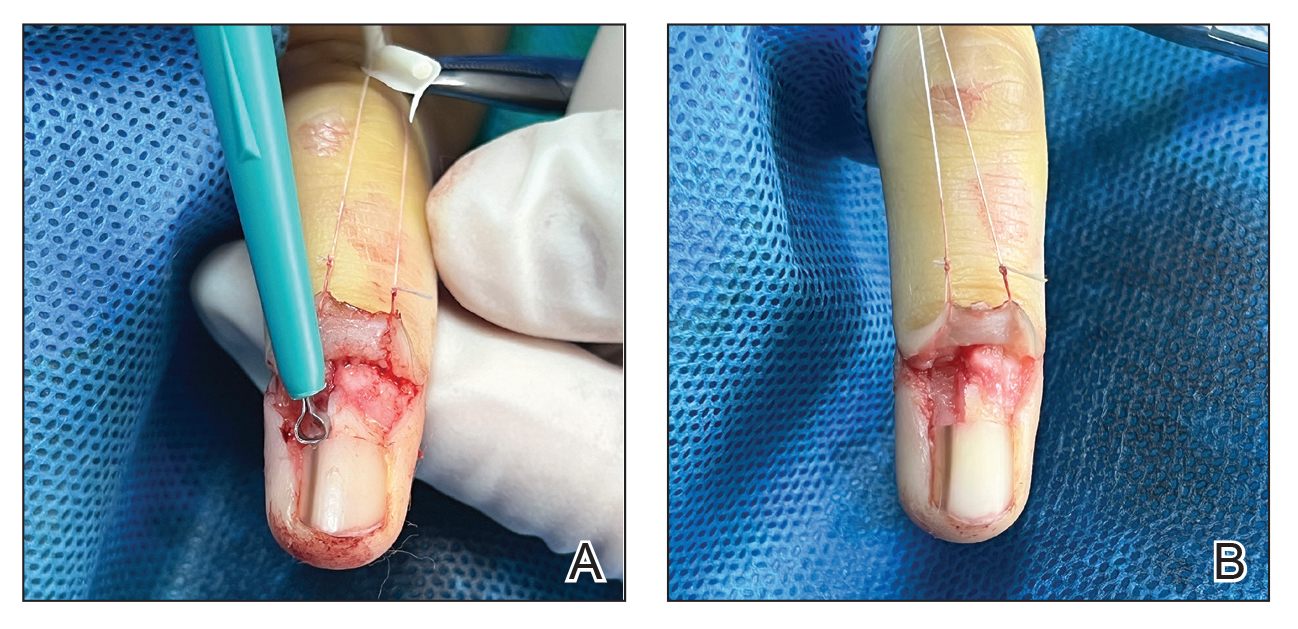

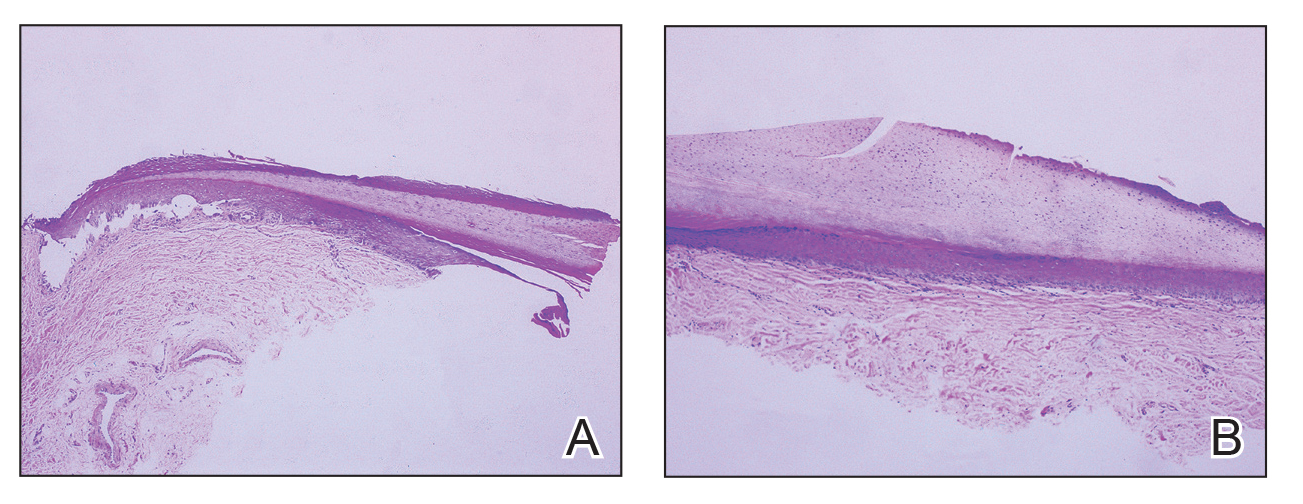

To repair this large defect, a full-thickness hinge flap with Burow graft was performed. The hinge-type flap was designed in a triangular fashion emanating at the posterior auricular sulcus adjacent to the posterior aspect of the defect and extending down the lateral neck (Figure 2). The flap was incised and the surrounding tissue was undermined, maintaining a robust pedicle in the center of its body on the superolateral neck. The flap was passed through the posterior aspect of the full-thickness defect and was secured in place with 4-0 polyglactin sutures in a buried interrupted fashion, thereby recreating the anterior portion of the defect. The superficial skin edges were reapproximated using 4-0 and 5-0 polypropylene sutures in a running interrupted fashion. The distal Burow triangle created from closure of the flap’s secondary defect was aggressively thinned and was utilized as a full-thickness graft for the residual postauricular groove defect (Figure 3). At 2 weeks’ follow-up, the patient was healing well with no postoperative issues and the sutures were removed (Figure 4).

Practice Implications

There are many different reconstructive options for conchal bowl defects, including primary repair, wedge excision, composite graft and interpolation flaps with or without cartilage struts, and hinge flaps. Structural support, EAC patency, auricle symmetry, overall auricle size, and re-creation of natural contours were considered when designing the reconstruction of the defect in our patient; however, his main priority was achieving the greatest cosmetic outcome in a single-stage procedure, therefore limiting our reconstruction options.

Wedge excision, in which the residual lobule and inferior helical rim are removed, could have been considered in our patient but would have drastically altered the symmetry of the size of the ears. A folded postauricular flap, as described in the otolaryngology literature, is an interpolation flap based on the posterior auricular artery that was designed for full-thickness defects of the auricle to prevent any posterior pinning.1 This technique may have worked well in our case, but the patient preferred to avoid a multistage procedure. Additionally, the positional symmetry of the ears was maintained despite utilizing a hinge flap, which does not involve takedown of the pedicle. A composite graft from the contralateral ear could be considered for smaller conchal bowl defects but likely would have resulted in graft failure in our patient’s large defect due to its need for rich blood supply to heal and dependence on lateral wound edges. Cartilage struts in conjunction with a flap could have been considered in this scenario for greater structural support, but in our patient’s case, by maintaining the robust pedicle of our flap and having residual superior cartilage, further structural support was not necessary.

A prior case report described a partial and full-thickness defect in a similar location that was repaired with a retroauricular hinge flap, in which a portion of the flap was extensively de-epithelialized to address the varied thicknesses of the surgical defect.2 In our patient, the defect abutted the skin reservoir on the superolateral neck, and therefore no de-epithelialization was required as the entire epithelialized portion was utilized to recreate the anterior aspect of the defect. Postauricular hinge-type flaps are a reliable, single-stage surgical alternative to the 2-stage folded postauricular interpolation flap when reconstructing large conchal bowl defects. For small full-thickness defects of the ear, a composite graft may be considered; however, blood supply and other nutritional requirements limit this option for large full-thickness defects.

- Roche AM, Griffin M, Shelton R, et al. The folded postauricular flap: a novel approach to reconstruction of large full thickness defects of the conchal bowl. Am J Otolaryngol. 2017;38:706-709. doi:10.1016 /j.amjoto.2017.09.006

- Klein JC, Nijhawan RI. Retroauricular hinge flaps for full-thickness conchal bowl defects. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:E71-E72. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.10.056

- Pickrell BB, Hughes CD, Maricevich RS. Partial ear defects. Semin Plast Surg. 2017 Aug;31:134-140. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1603968.

Practice Gap

Large full-thickness conchal bowl defects often pose a reconstructive challenge. Maintaining the shape and structural integrity of the concha is fundamental for optimal cosmetic and functional outcomes. Prior reports have suggested wedge excisions, composite grafts, interpolation flaps with or without cartilage struts, and hinge flaps as possible options for reconstruction.1-3 However, patients with large defects who prefer single-stage reconstruction procedures present a unique challenge. Herein, we describe a single-stage full-thickness hinge flap technique for a large conchal bowl defect.

The Technique

A 77-year-old man was referred to our dermatology clinic by an outside dermatologist for Mohs micrographic surgery of a biopsy-proven cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma on the right conchal bowl measuring 1.1×2.1 cm and extending to the edge of the external auditory canal (EAC). The excision was performed that same day and was completed in 2 stages, achieving negative margins and resulting in a full-thickness defect measuring 2.0×3.6 cm that included the posterior auricular sulcus, cavum, antitragus, and proximal EAC (Figure 1). The patient requested a single-stage procedure but emphasized that his main priority was an optimal cosmetic outcome.

To repair this large defect, a full-thickness hinge flap with Burow graft was performed. The hinge-type flap was designed in a triangular fashion emanating at the posterior auricular sulcus adjacent to the posterior aspect of the defect and extending down the lateral neck (Figure 2). The flap was incised and the surrounding tissue was undermined, maintaining a robust pedicle in the center of its body on the superolateral neck. The flap was passed through the posterior aspect of the full-thickness defect and was secured in place with 4-0 polyglactin sutures in a buried interrupted fashion, thereby recreating the anterior portion of the defect. The superficial skin edges were reapproximated using 4-0 and 5-0 polypropylene sutures in a running interrupted fashion. The distal Burow triangle created from closure of the flap’s secondary defect was aggressively thinned and was utilized as a full-thickness graft for the residual postauricular groove defect (Figure 3). At 2 weeks’ follow-up, the patient was healing well with no postoperative issues and the sutures were removed (Figure 4).

Practice Implications

There are many different reconstructive options for conchal bowl defects, including primary repair, wedge excision, composite graft and interpolation flaps with or without cartilage struts, and hinge flaps. Structural support, EAC patency, auricle symmetry, overall auricle size, and re-creation of natural contours were considered when designing the reconstruction of the defect in our patient; however, his main priority was achieving the greatest cosmetic outcome in a single-stage procedure, therefore limiting our reconstruction options.

Wedge excision, in which the residual lobule and inferior helical rim are removed, could have been considered in our patient but would have drastically altered the symmetry of the size of the ears. A folded postauricular flap, as described in the otolaryngology literature, is an interpolation flap based on the posterior auricular artery that was designed for full-thickness defects of the auricle to prevent any posterior pinning.1 This technique may have worked well in our case, but the patient preferred to avoid a multistage procedure. Additionally, the positional symmetry of the ears was maintained despite utilizing a hinge flap, which does not involve takedown of the pedicle. A composite graft from the contralateral ear could be considered for smaller conchal bowl defects but likely would have resulted in graft failure in our patient’s large defect due to its need for rich blood supply to heal and dependence on lateral wound edges. Cartilage struts in conjunction with a flap could have been considered in this scenario for greater structural support, but in our patient’s case, by maintaining the robust pedicle of our flap and having residual superior cartilage, further structural support was not necessary.

A prior case report described a partial and full-thickness defect in a similar location that was repaired with a retroauricular hinge flap, in which a portion of the flap was extensively de-epithelialized to address the varied thicknesses of the surgical defect.2 In our patient, the defect abutted the skin reservoir on the superolateral neck, and therefore no de-epithelialization was required as the entire epithelialized portion was utilized to recreate the anterior aspect of the defect. Postauricular hinge-type flaps are a reliable, single-stage surgical alternative to the 2-stage folded postauricular interpolation flap when reconstructing large conchal bowl defects. For small full-thickness defects of the ear, a composite graft may be considered; however, blood supply and other nutritional requirements limit this option for large full-thickness defects.

Practice Gap

Large full-thickness conchal bowl defects often pose a reconstructive challenge. Maintaining the shape and structural integrity of the concha is fundamental for optimal cosmetic and functional outcomes. Prior reports have suggested wedge excisions, composite grafts, interpolation flaps with or without cartilage struts, and hinge flaps as possible options for reconstruction.1-3 However, patients with large defects who prefer single-stage reconstruction procedures present a unique challenge. Herein, we describe a single-stage full-thickness hinge flap technique for a large conchal bowl defect.

The Technique

A 77-year-old man was referred to our dermatology clinic by an outside dermatologist for Mohs micrographic surgery of a biopsy-proven cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma on the right conchal bowl measuring 1.1×2.1 cm and extending to the edge of the external auditory canal (EAC). The excision was performed that same day and was completed in 2 stages, achieving negative margins and resulting in a full-thickness defect measuring 2.0×3.6 cm that included the posterior auricular sulcus, cavum, antitragus, and proximal EAC (Figure 1). The patient requested a single-stage procedure but emphasized that his main priority was an optimal cosmetic outcome.

To repair this large defect, a full-thickness hinge flap with Burow graft was performed. The hinge-type flap was designed in a triangular fashion emanating at the posterior auricular sulcus adjacent to the posterior aspect of the defect and extending down the lateral neck (Figure 2). The flap was incised and the surrounding tissue was undermined, maintaining a robust pedicle in the center of its body on the superolateral neck. The flap was passed through the posterior aspect of the full-thickness defect and was secured in place with 4-0 polyglactin sutures in a buried interrupted fashion, thereby recreating the anterior portion of the defect. The superficial skin edges were reapproximated using 4-0 and 5-0 polypropylene sutures in a running interrupted fashion. The distal Burow triangle created from closure of the flap’s secondary defect was aggressively thinned and was utilized as a full-thickness graft for the residual postauricular groove defect (Figure 3). At 2 weeks’ follow-up, the patient was healing well with no postoperative issues and the sutures were removed (Figure 4).

Practice Implications

There are many different reconstructive options for conchal bowl defects, including primary repair, wedge excision, composite graft and interpolation flaps with or without cartilage struts, and hinge flaps. Structural support, EAC patency, auricle symmetry, overall auricle size, and re-creation of natural contours were considered when designing the reconstruction of the defect in our patient; however, his main priority was achieving the greatest cosmetic outcome in a single-stage procedure, therefore limiting our reconstruction options.

Wedge excision, in which the residual lobule and inferior helical rim are removed, could have been considered in our patient but would have drastically altered the symmetry of the size of the ears. A folded postauricular flap, as described in the otolaryngology literature, is an interpolation flap based on the posterior auricular artery that was designed for full-thickness defects of the auricle to prevent any posterior pinning.1 This technique may have worked well in our case, but the patient preferred to avoid a multistage procedure. Additionally, the positional symmetry of the ears was maintained despite utilizing a hinge flap, which does not involve takedown of the pedicle. A composite graft from the contralateral ear could be considered for smaller conchal bowl defects but likely would have resulted in graft failure in our patient’s large defect due to its need for rich blood supply to heal and dependence on lateral wound edges. Cartilage struts in conjunction with a flap could have been considered in this scenario for greater structural support, but in our patient’s case, by maintaining the robust pedicle of our flap and having residual superior cartilage, further structural support was not necessary.

A prior case report described a partial and full-thickness defect in a similar location that was repaired with a retroauricular hinge flap, in which a portion of the flap was extensively de-epithelialized to address the varied thicknesses of the surgical defect.2 In our patient, the defect abutted the skin reservoir on the superolateral neck, and therefore no de-epithelialization was required as the entire epithelialized portion was utilized to recreate the anterior aspect of the defect. Postauricular hinge-type flaps are a reliable, single-stage surgical alternative to the 2-stage folded postauricular interpolation flap when reconstructing large conchal bowl defects. For small full-thickness defects of the ear, a composite graft may be considered; however, blood supply and other nutritional requirements limit this option for large full-thickness defects.

- Roche AM, Griffin M, Shelton R, et al. The folded postauricular flap: a novel approach to reconstruction of large full thickness defects of the conchal bowl. Am J Otolaryngol. 2017;38:706-709. doi:10.1016 /j.amjoto.2017.09.006

- Klein JC, Nijhawan RI. Retroauricular hinge flaps for full-thickness conchal bowl defects. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:E71-E72. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.10.056

- Pickrell BB, Hughes CD, Maricevich RS. Partial ear defects. Semin Plast Surg. 2017 Aug;31:134-140. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1603968.

- Roche AM, Griffin M, Shelton R, et al. The folded postauricular flap: a novel approach to reconstruction of large full thickness defects of the conchal bowl. Am J Otolaryngol. 2017;38:706-709. doi:10.1016 /j.amjoto.2017.09.006

- Klein JC, Nijhawan RI. Retroauricular hinge flaps for full-thickness conchal bowl defects. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:E71-E72. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.10.056

- Pickrell BB, Hughes CD, Maricevich RS. Partial ear defects. Semin Plast Surg. 2017 Aug;31:134-140. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1603968.

Repair of a Large Full-Thickness Conchal Bowl Defect

Repair of a Large Full-Thickness Conchal Bowl Defect

Using Superficial Curettage to Diagnose Talon Noir

Using Superficial Curettage to Diagnose Talon Noir

Practice Gap

Brown macules on the feet can pose diagnostic challenges, often raising suspicion of acral melanoma. Talon noir, which is benign and self-resolving, is characterized by dark patches on the skin of the feet due to hemorrhage within the stratum corneum and commonly is observed in athletes who sustain repetitive foot trauma. In one study, nearly 50% (9/20) of talon noir cases initially were misdiagnosed as acral melanoma or melanocytic nevi.1 Accurate identification of talon noir is essential to prevent unnecessary interventions or delayed treatment of malignant lesions. Here, we describe a low-risk, cost-effective, and time-efficient diagnostic technique for talon noir using a disposable curette to potentially avoid more invasive procedures.

The Technique

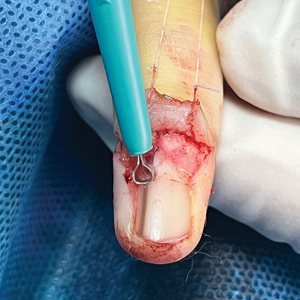

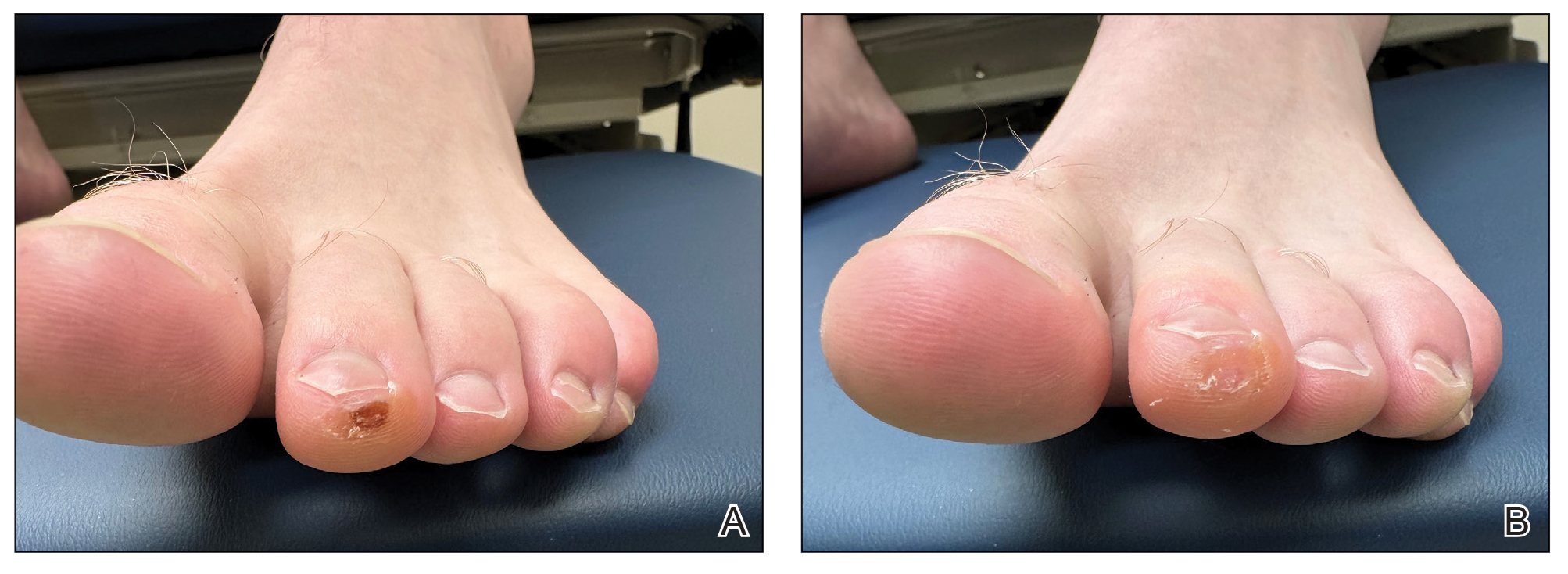

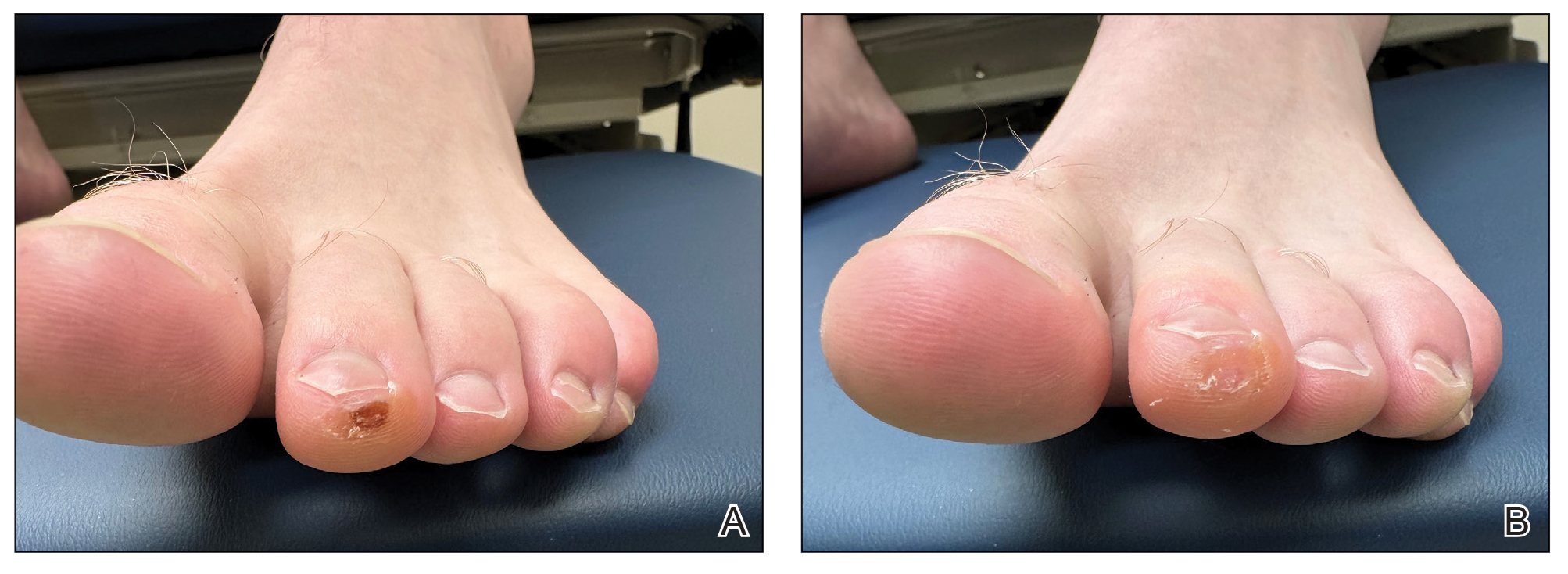

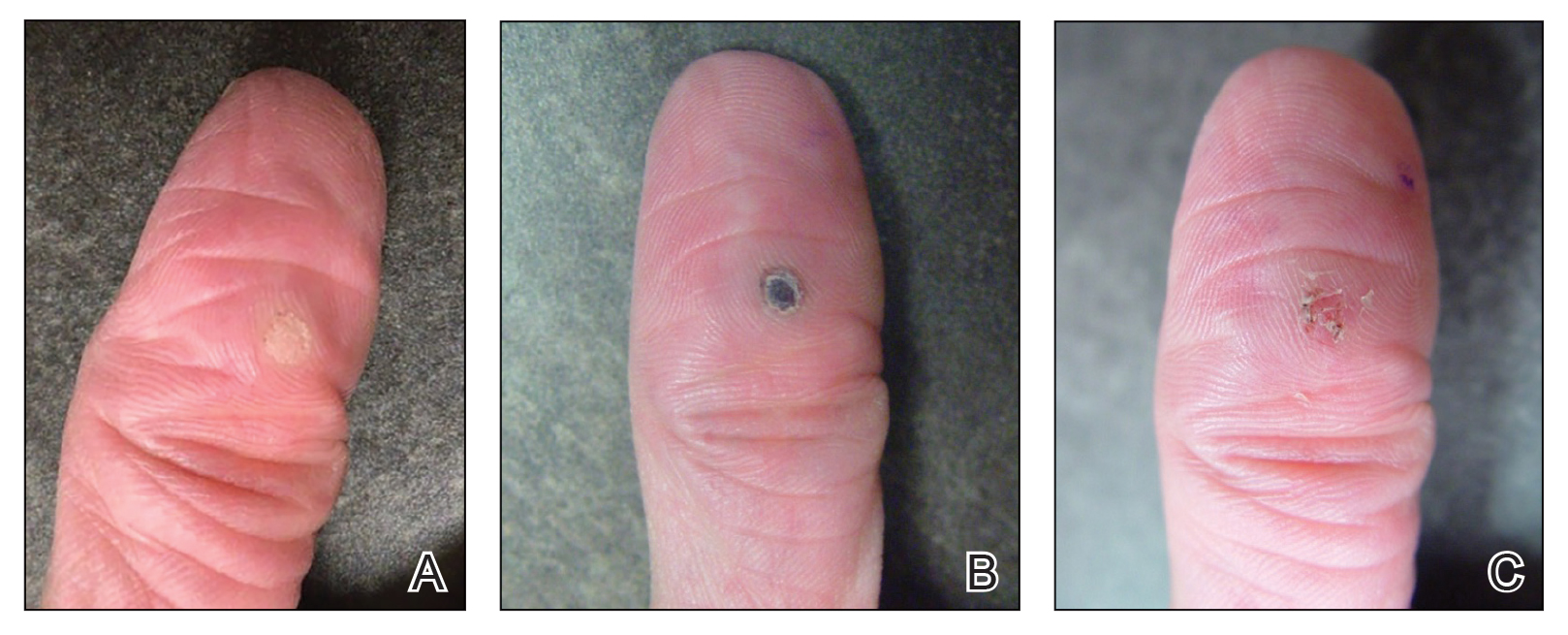

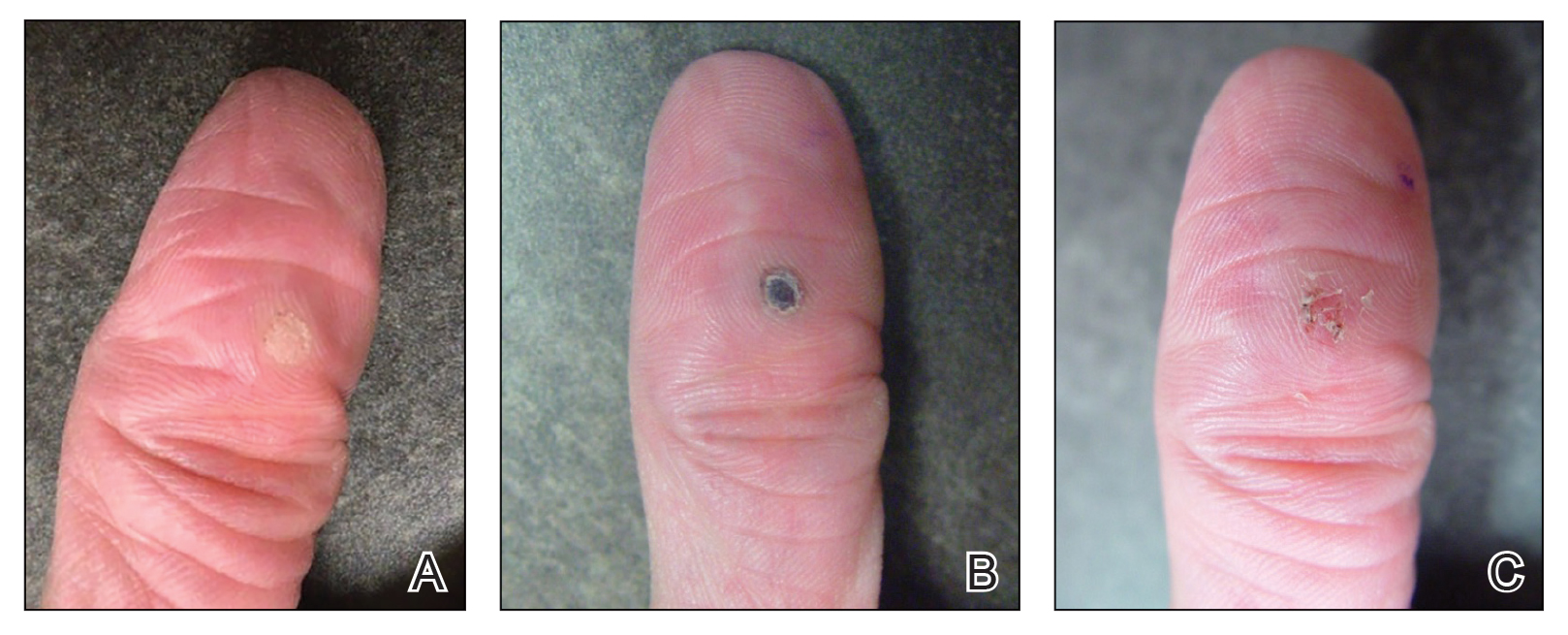

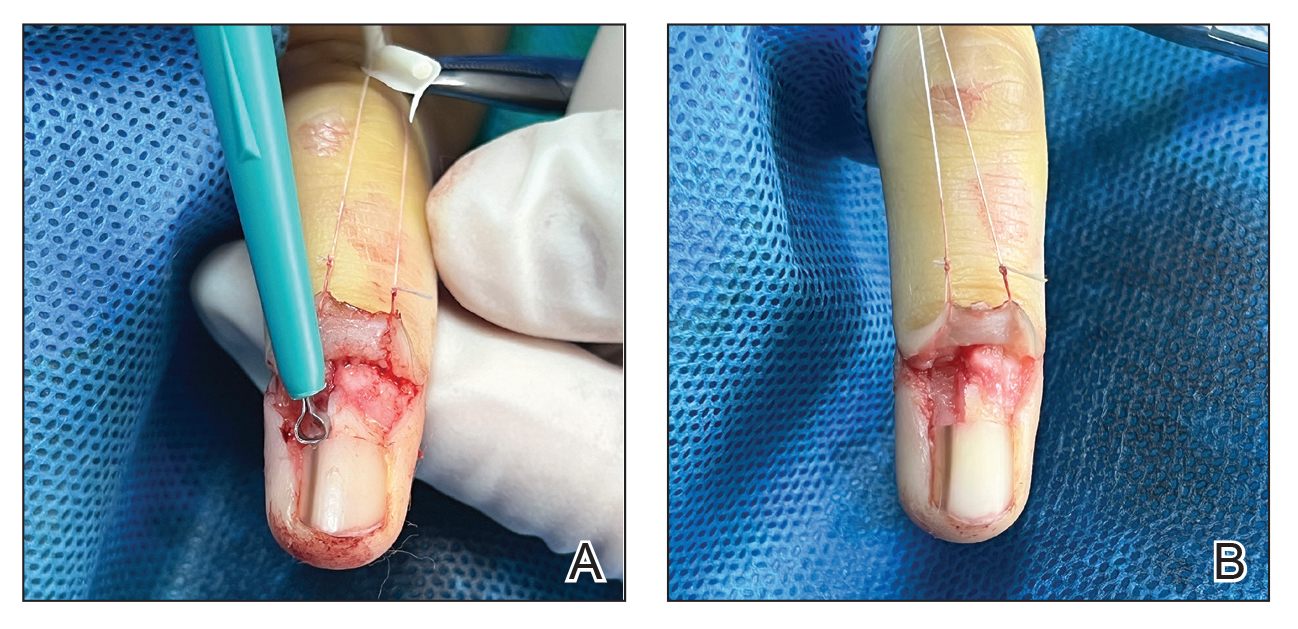

A 34-year-old man presented to the dermatology department with a new brown macule on the second toe. The lesion had been present and stable for more than 4 months, showing no changes in shape or color. The patient reported that he was a frequent runner but did not recall any trauma to the toe, and he denied any associated pain, pruritus, or bleeding. Physical examination revealed a 6-mm dark-brown macule on the hyponychium of the left second toe, with numerous petechiae noted on dermoscopic examination. The findings were consistent with talon noir.

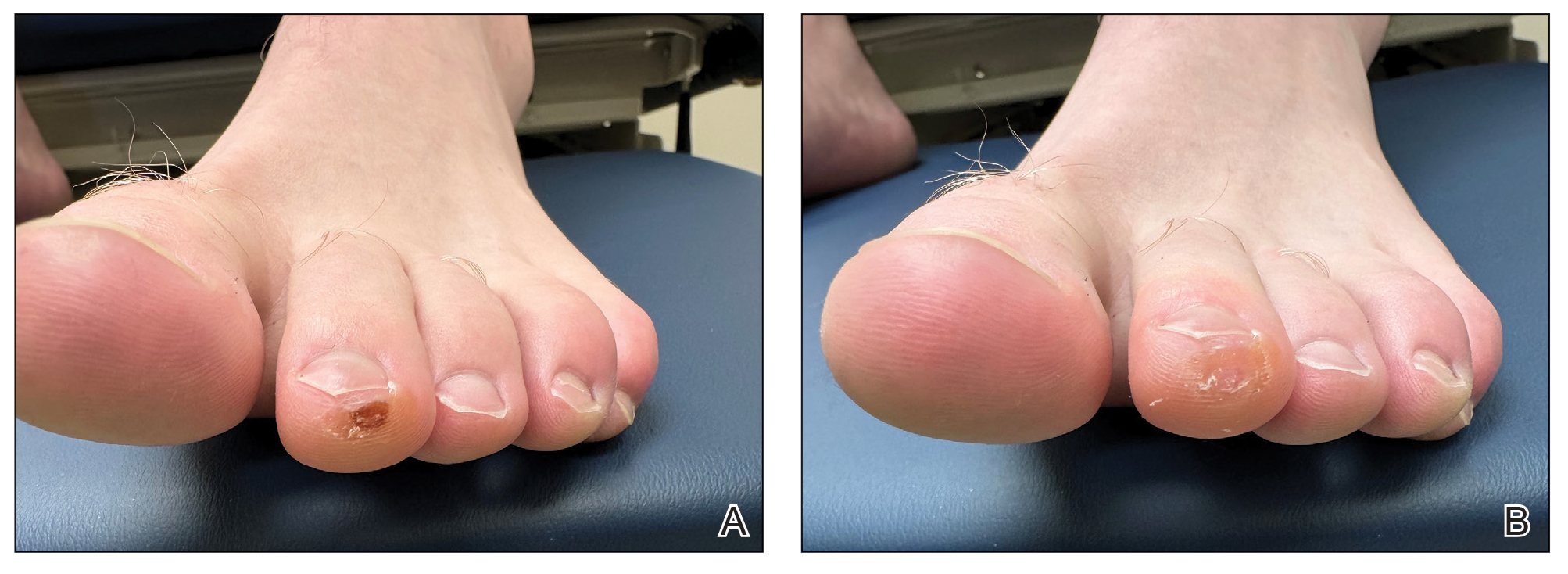

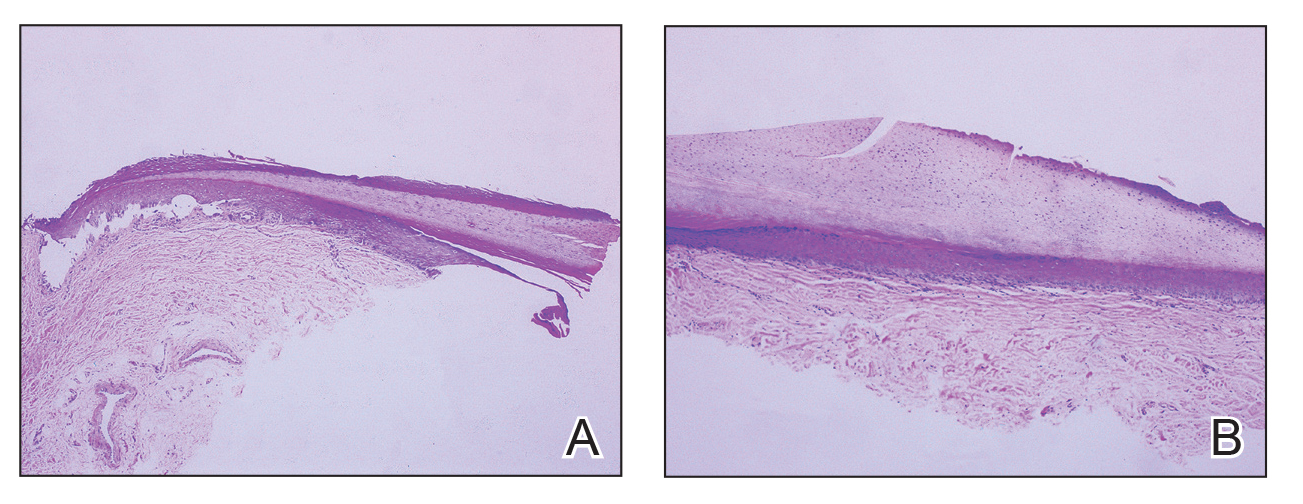

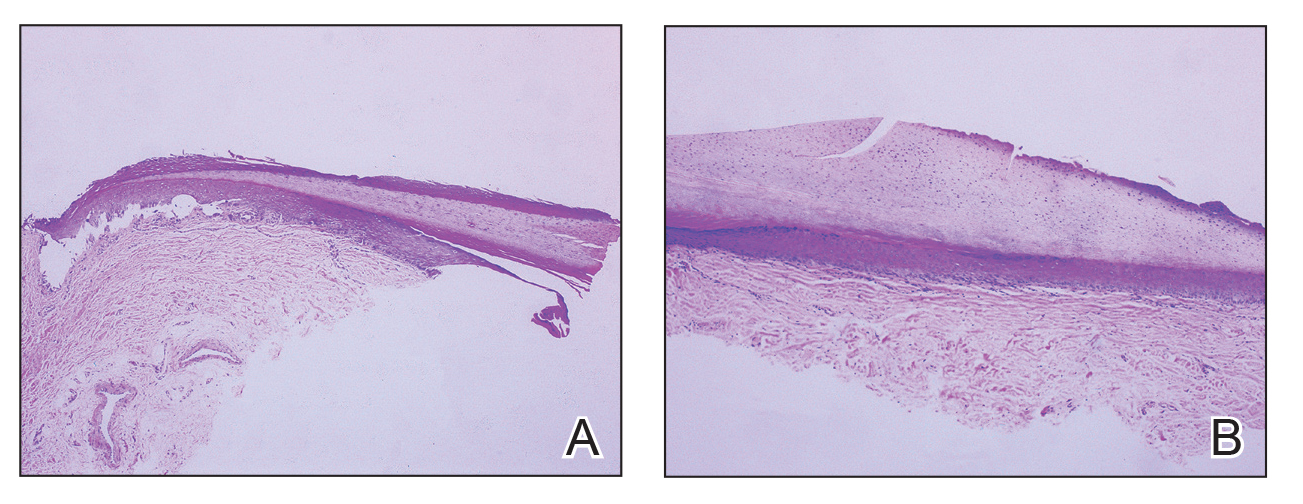

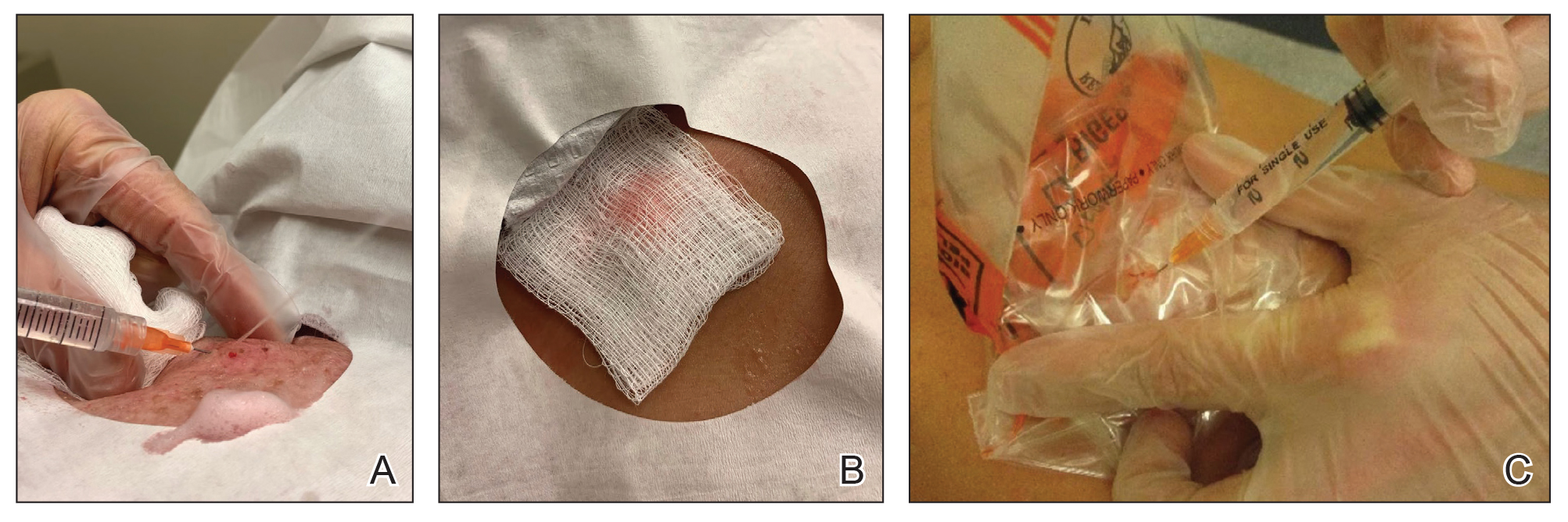

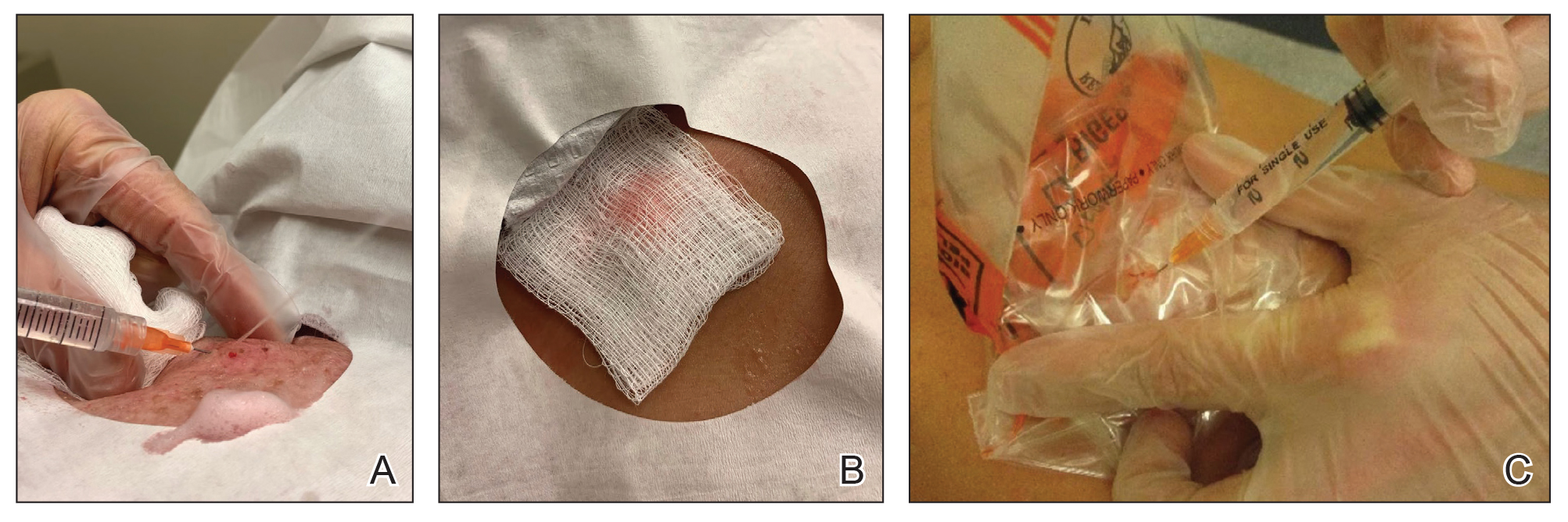

Given the clinical suspicion of talon noir, we used a 5-mm disposable curette to gently pare the superficial epidermis. The superficial curettage effectively removed the lesion, leaving behind a healthy epidermis with no pinpoint bleeding, which confirmed the diagnosis of talon noir (Figure). Pathologic changes from acral melanoma reside deeper than talon noir and consequently cannot be effectively removed by superficial curettage alone. Curettage acts as a curative technique for talon noir, but also as a low-risk, cost-effective, and time-efficient diagnostic technique to rule out insidious diagnoses, including acral melanoma.2 A follow-up examination performed several weeks later showed no pigmentation or recurrence of the lesion in our patient, further supporting the diagnosis of talon noir.

Practice Implications

Talon noir refers to localized accumulation of blood within the epidermis due to repetitive trauma, pressure, and shearing forces on the skin that results in pigmented macules.3-5 Repetitive trauma damages the microvasculature in areas of the skin with minimal subcutaneous adipose tissue.6 Talon noir also is known as subcorneal hematoma, intracorneal hematoma, black heel, hyperkeratosis hemorrhagica, and basketball heel.1,3 First described by Crissey and Peachey3 in 1961 as calcaneal petechiae, the condition was identified in basketball players with well-circumscribed, deep-red lesions on the posterior lateral heels, located between the Achilles tendon insertion and calcaneal fat pad.3 Subsequent reports have documented talon noir in athletes from a range of sports such as tennis and football, whose activities involve rapid directional changes and shearing forces on the feet.6 Similar lesions, termed tache noir, have been observed on the hands of athletes including gymnasts, weightlifters, golfers, and climbers due to repetitive hand trauma.6 Gross examination reveals blood collecting in the thickened stratum corneum.5

The cutaneous manifestations of talon noir can mimic acral melanoma, highlighting the need for dermatologists to understand its clinical, dermoscopic, and microscopic features. Poor patient recall can complicate diagnosis; for instance, in one study only 20% (4/20) of patients remembered the inciting trauma that caused the subcorneal hematomas.1 Balancing vigilance for melanoma with recognition of more benign conditions such as talon noir—particularly in younger active populations—is essential to minimize patient anxiety and avoid invasive procedures.

Further investigation is warranted in lesions that persist without obvious cause or in those that demonstrate concerning features such as extensive growth. One case of talon noir in a patient with diabetes required an excisional biopsy due to its atypical progression over 1 year with considerable hyperpigmentation and friability.7 Additional investigation such as dermoscopy may be required with paring of the skin to establish a diagnosis.1 Using a curette to pare the thickened stratum corneum, which has no nerve endings, does not require anesthetics.8 In talon noir, paring completely removes the lesion, leaving behind unaffected skin, while melanomas would retain their pigmentation due to melanin in the basal layer.2

Talon noir is a benign condition frequently misdiagnosed due to its resemblance to more serious pathologies such as melanoma. Awareness of its clinical and dermoscopic features can promote cost-effective care while reducing unnecessary procedures. Diagnostic paring of the skin with a curette offers a simple and reliable means of distinguishing talon noir from acral melanoma and other potential conditions.

- Elmas OF, Akdeniz N. Subcorneal hematoma as an imitator of acral melanoma: dermoscopic diagnosis. North Clin Istanb. 2019;7:56-59. doi:10.14744/nci.2019.65481

- Googe AB, Schulmeier JS, Jackson AR, et al. Talon noir: paring can eliminate the need for a biopsy. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:730-731. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2014-132996

- Crissey JT, Peachey JC. Calcaneal petechiae. Arch Dermatol. 1961;83:501. doi:10.1001/archderm.1961.01580090151017

- Martin SB, Lucas JK, Posa M, et al. Talon noir in a young baseball player: a case report. J Pediatr Health Care. 2021;35:235-238. doi:10.1016 /j.pedhc.2020.10.009

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al. Dermatology Essentials. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2022.

- Emer J, Sivek R, Marciniak B. Sports dermatology: part 1 of 2 traumatic or mechanical injuries, inflammatory conditions, and exacerbations of pre-existing conditions. J Clin Aesthetic Dermatol. 2015; 8:31-43.

- Choudhury S, Mandal A. Talon noir: a case report and literature review. Cureus. 2023;15:E35905. doi:10.7759/cureus.35905

- Oberdorfer KL, Farshchian M, Moossavi M. Paring of skin for superficially lodged foreign body removal. Cureus. 2023;15:E42396. doi:10.7759/cureus.42396

Practice Gap

Brown macules on the feet can pose diagnostic challenges, often raising suspicion of acral melanoma. Talon noir, which is benign and self-resolving, is characterized by dark patches on the skin of the feet due to hemorrhage within the stratum corneum and commonly is observed in athletes who sustain repetitive foot trauma. In one study, nearly 50% (9/20) of talon noir cases initially were misdiagnosed as acral melanoma or melanocytic nevi.1 Accurate identification of talon noir is essential to prevent unnecessary interventions or delayed treatment of malignant lesions. Here, we describe a low-risk, cost-effective, and time-efficient diagnostic technique for talon noir using a disposable curette to potentially avoid more invasive procedures.

The Technique

A 34-year-old man presented to the dermatology department with a new brown macule on the second toe. The lesion had been present and stable for more than 4 months, showing no changes in shape or color. The patient reported that he was a frequent runner but did not recall any trauma to the toe, and he denied any associated pain, pruritus, or bleeding. Physical examination revealed a 6-mm dark-brown macule on the hyponychium of the left second toe, with numerous petechiae noted on dermoscopic examination. The findings were consistent with talon noir.

Given the clinical suspicion of talon noir, we used a 5-mm disposable curette to gently pare the superficial epidermis. The superficial curettage effectively removed the lesion, leaving behind a healthy epidermis with no pinpoint bleeding, which confirmed the diagnosis of talon noir (Figure). Pathologic changes from acral melanoma reside deeper than talon noir and consequently cannot be effectively removed by superficial curettage alone. Curettage acts as a curative technique for talon noir, but also as a low-risk, cost-effective, and time-efficient diagnostic technique to rule out insidious diagnoses, including acral melanoma.2 A follow-up examination performed several weeks later showed no pigmentation or recurrence of the lesion in our patient, further supporting the diagnosis of talon noir.

Practice Implications

Talon noir refers to localized accumulation of blood within the epidermis due to repetitive trauma, pressure, and shearing forces on the skin that results in pigmented macules.3-5 Repetitive trauma damages the microvasculature in areas of the skin with minimal subcutaneous adipose tissue.6 Talon noir also is known as subcorneal hematoma, intracorneal hematoma, black heel, hyperkeratosis hemorrhagica, and basketball heel.1,3 First described by Crissey and Peachey3 in 1961 as calcaneal petechiae, the condition was identified in basketball players with well-circumscribed, deep-red lesions on the posterior lateral heels, located between the Achilles tendon insertion and calcaneal fat pad.3 Subsequent reports have documented talon noir in athletes from a range of sports such as tennis and football, whose activities involve rapid directional changes and shearing forces on the feet.6 Similar lesions, termed tache noir, have been observed on the hands of athletes including gymnasts, weightlifters, golfers, and climbers due to repetitive hand trauma.6 Gross examination reveals blood collecting in the thickened stratum corneum.5

The cutaneous manifestations of talon noir can mimic acral melanoma, highlighting the need for dermatologists to understand its clinical, dermoscopic, and microscopic features. Poor patient recall can complicate diagnosis; for instance, in one study only 20% (4/20) of patients remembered the inciting trauma that caused the subcorneal hematomas.1 Balancing vigilance for melanoma with recognition of more benign conditions such as talon noir—particularly in younger active populations—is essential to minimize patient anxiety and avoid invasive procedures.

Further investigation is warranted in lesions that persist without obvious cause or in those that demonstrate concerning features such as extensive growth. One case of talon noir in a patient with diabetes required an excisional biopsy due to its atypical progression over 1 year with considerable hyperpigmentation and friability.7 Additional investigation such as dermoscopy may be required with paring of the skin to establish a diagnosis.1 Using a curette to pare the thickened stratum corneum, which has no nerve endings, does not require anesthetics.8 In talon noir, paring completely removes the lesion, leaving behind unaffected skin, while melanomas would retain their pigmentation due to melanin in the basal layer.2

Talon noir is a benign condition frequently misdiagnosed due to its resemblance to more serious pathologies such as melanoma. Awareness of its clinical and dermoscopic features can promote cost-effective care while reducing unnecessary procedures. Diagnostic paring of the skin with a curette offers a simple and reliable means of distinguishing talon noir from acral melanoma and other potential conditions.

Practice Gap

Brown macules on the feet can pose diagnostic challenges, often raising suspicion of acral melanoma. Talon noir, which is benign and self-resolving, is characterized by dark patches on the skin of the feet due to hemorrhage within the stratum corneum and commonly is observed in athletes who sustain repetitive foot trauma. In one study, nearly 50% (9/20) of talon noir cases initially were misdiagnosed as acral melanoma or melanocytic nevi.1 Accurate identification of talon noir is essential to prevent unnecessary interventions or delayed treatment of malignant lesions. Here, we describe a low-risk, cost-effective, and time-efficient diagnostic technique for talon noir using a disposable curette to potentially avoid more invasive procedures.

The Technique

A 34-year-old man presented to the dermatology department with a new brown macule on the second toe. The lesion had been present and stable for more than 4 months, showing no changes in shape or color. The patient reported that he was a frequent runner but did not recall any trauma to the toe, and he denied any associated pain, pruritus, or bleeding. Physical examination revealed a 6-mm dark-brown macule on the hyponychium of the left second toe, with numerous petechiae noted on dermoscopic examination. The findings were consistent with talon noir.

Given the clinical suspicion of talon noir, we used a 5-mm disposable curette to gently pare the superficial epidermis. The superficial curettage effectively removed the lesion, leaving behind a healthy epidermis with no pinpoint bleeding, which confirmed the diagnosis of talon noir (Figure). Pathologic changes from acral melanoma reside deeper than talon noir and consequently cannot be effectively removed by superficial curettage alone. Curettage acts as a curative technique for talon noir, but also as a low-risk, cost-effective, and time-efficient diagnostic technique to rule out insidious diagnoses, including acral melanoma.2 A follow-up examination performed several weeks later showed no pigmentation or recurrence of the lesion in our patient, further supporting the diagnosis of talon noir.

Practice Implications

Talon noir refers to localized accumulation of blood within the epidermis due to repetitive trauma, pressure, and shearing forces on the skin that results in pigmented macules.3-5 Repetitive trauma damages the microvasculature in areas of the skin with minimal subcutaneous adipose tissue.6 Talon noir also is known as subcorneal hematoma, intracorneal hematoma, black heel, hyperkeratosis hemorrhagica, and basketball heel.1,3 First described by Crissey and Peachey3 in 1961 as calcaneal petechiae, the condition was identified in basketball players with well-circumscribed, deep-red lesions on the posterior lateral heels, located between the Achilles tendon insertion and calcaneal fat pad.3 Subsequent reports have documented talon noir in athletes from a range of sports such as tennis and football, whose activities involve rapid directional changes and shearing forces on the feet.6 Similar lesions, termed tache noir, have been observed on the hands of athletes including gymnasts, weightlifters, golfers, and climbers due to repetitive hand trauma.6 Gross examination reveals blood collecting in the thickened stratum corneum.5

The cutaneous manifestations of talon noir can mimic acral melanoma, highlighting the need for dermatologists to understand its clinical, dermoscopic, and microscopic features. Poor patient recall can complicate diagnosis; for instance, in one study only 20% (4/20) of patients remembered the inciting trauma that caused the subcorneal hematomas.1 Balancing vigilance for melanoma with recognition of more benign conditions such as talon noir—particularly in younger active populations—is essential to minimize patient anxiety and avoid invasive procedures.

Further investigation is warranted in lesions that persist without obvious cause or in those that demonstrate concerning features such as extensive growth. One case of talon noir in a patient with diabetes required an excisional biopsy due to its atypical progression over 1 year with considerable hyperpigmentation and friability.7 Additional investigation such as dermoscopy may be required with paring of the skin to establish a diagnosis.1 Using a curette to pare the thickened stratum corneum, which has no nerve endings, does not require anesthetics.8 In talon noir, paring completely removes the lesion, leaving behind unaffected skin, while melanomas would retain their pigmentation due to melanin in the basal layer.2

Talon noir is a benign condition frequently misdiagnosed due to its resemblance to more serious pathologies such as melanoma. Awareness of its clinical and dermoscopic features can promote cost-effective care while reducing unnecessary procedures. Diagnostic paring of the skin with a curette offers a simple and reliable means of distinguishing talon noir from acral melanoma and other potential conditions.

- Elmas OF, Akdeniz N. Subcorneal hematoma as an imitator of acral melanoma: dermoscopic diagnosis. North Clin Istanb. 2019;7:56-59. doi:10.14744/nci.2019.65481

- Googe AB, Schulmeier JS, Jackson AR, et al. Talon noir: paring can eliminate the need for a biopsy. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:730-731. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2014-132996

- Crissey JT, Peachey JC. Calcaneal petechiae. Arch Dermatol. 1961;83:501. doi:10.1001/archderm.1961.01580090151017

- Martin SB, Lucas JK, Posa M, et al. Talon noir in a young baseball player: a case report. J Pediatr Health Care. 2021;35:235-238. doi:10.1016 /j.pedhc.2020.10.009

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al. Dermatology Essentials. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2022.

- Emer J, Sivek R, Marciniak B. Sports dermatology: part 1 of 2 traumatic or mechanical injuries, inflammatory conditions, and exacerbations of pre-existing conditions. J Clin Aesthetic Dermatol. 2015; 8:31-43.

- Choudhury S, Mandal A. Talon noir: a case report and literature review. Cureus. 2023;15:E35905. doi:10.7759/cureus.35905

- Oberdorfer KL, Farshchian M, Moossavi M. Paring of skin for superficially lodged foreign body removal. Cureus. 2023;15:E42396. doi:10.7759/cureus.42396

- Elmas OF, Akdeniz N. Subcorneal hematoma as an imitator of acral melanoma: dermoscopic diagnosis. North Clin Istanb. 2019;7:56-59. doi:10.14744/nci.2019.65481

- Googe AB, Schulmeier JS, Jackson AR, et al. Talon noir: paring can eliminate the need for a biopsy. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:730-731. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2014-132996

- Crissey JT, Peachey JC. Calcaneal petechiae. Arch Dermatol. 1961;83:501. doi:10.1001/archderm.1961.01580090151017

- Martin SB, Lucas JK, Posa M, et al. Talon noir in a young baseball player: a case report. J Pediatr Health Care. 2021;35:235-238. doi:10.1016 /j.pedhc.2020.10.009

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al. Dermatology Essentials. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2022.

- Emer J, Sivek R, Marciniak B. Sports dermatology: part 1 of 2 traumatic or mechanical injuries, inflammatory conditions, and exacerbations of pre-existing conditions. J Clin Aesthetic Dermatol. 2015; 8:31-43.

- Choudhury S, Mandal A. Talon noir: a case report and literature review. Cureus. 2023;15:E35905. doi:10.7759/cureus.35905

- Oberdorfer KL, Farshchian M, Moossavi M. Paring of skin for superficially lodged foreign body removal. Cureus. 2023;15:E42396. doi:10.7759/cureus.42396

Using Superficial Curettage to Diagnose Talon Noir

Using Superficial Curettage to Diagnose Talon Noir

Ergonomics in Dermatologic Procedures: Mobility Exercises to Incorporate In and Out of the Office

Ergonomics in Dermatologic Procedures: Mobility Exercises to Incorporate In and Out of the Office

Practice Gap

Dermatology encompasses a wide range of procedures performed in both clinical and surgical settings. One comprehensive review of ergonomics in dermatologic surgery found a high prevalence of musculoskeletal injuries (MSIs).1 A survey conducted in 2010 revealed that 90% of dermatologic surgeons experienced MSIs, which commonly resulted in neck, shoulder, and/or back pain.2

Prolonged abnormal static postures and repetitive motions, which are common in dermatologic practice, can lead to muscle imbalances and focal muscular ischemia, increasing physicians’ susceptibility to MSIs. When muscle fibers experience enough repeated focal ischemia, they may enter a constant state of contraction leading to myofascial pain syndrome (MPS); these painful areas are known as trigger points and often are refractory to traditional stretching.3

Musculoskeletal injuries can potentially impact dermatologists’ career longevity and satisfaction. To date, the literature on techniques and exercises that may prevent or alleviate MSIs is limited.1,4 We collaborated with a colleague in physical therapy (R.P.) to present stretching, mobility, and strengthening techniques and exercises dermatologists can perform both in and outside the procedure room to potentially reduce pain and prevent future MSIs.

The Techniques

Stretching and Mobility Exercises—When dermatologists adopt abnormal static postures, they are at risk for muscular imbalances caused by repetitive flexion and/or rotation in one direction. Over time, these repetitive movements can result in loss of flexibility in the direction opposite to that in which they are consistently positioned.3 Regular stretching offers physiologic benefits such as maintaining joint range of motion, increasing blood flow to muscles, and increasing synovial fluid production—all of which contribute to reduced risk for MSIs.3 Multiple studies and a systematic review have found that regular stretching throughout the day serves as an effective method for preventing and mitigating MSI pain in health care providers.1,3-5

Considering the directional manner of MSIs induced by prolonged static positions, the most benefit will be derived from stretches or extension in the opposite direction of that in which the practitioner usually works. For most dermatologic surgeons, stretches should target the trapezius muscles, shoulders, and cervical musculature. Techniques such as the neck and shoulder combination stretch, the upper trapezius stretch, and the downward shoulder blade squeeze stretch can be performed regularly throughout the day.3,4 To perform the neck and shoulder combination stretch, place the arm in flexion to shoulder height and bend the elbow at a 90° angle. Gently pull the arm across the front of the body, point the head gazing in the direction of the shoulder being stretched, and hold for 10 to 20 seconds. Repeat with the other side (eFigure 1).

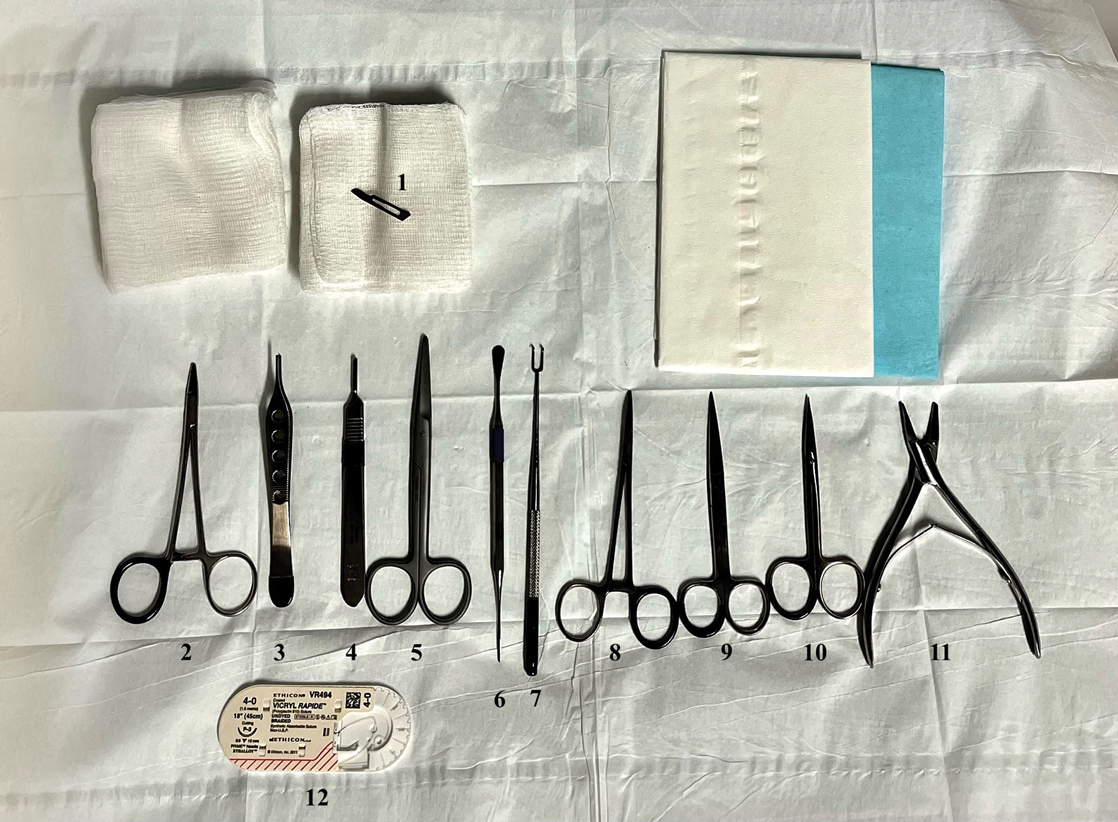

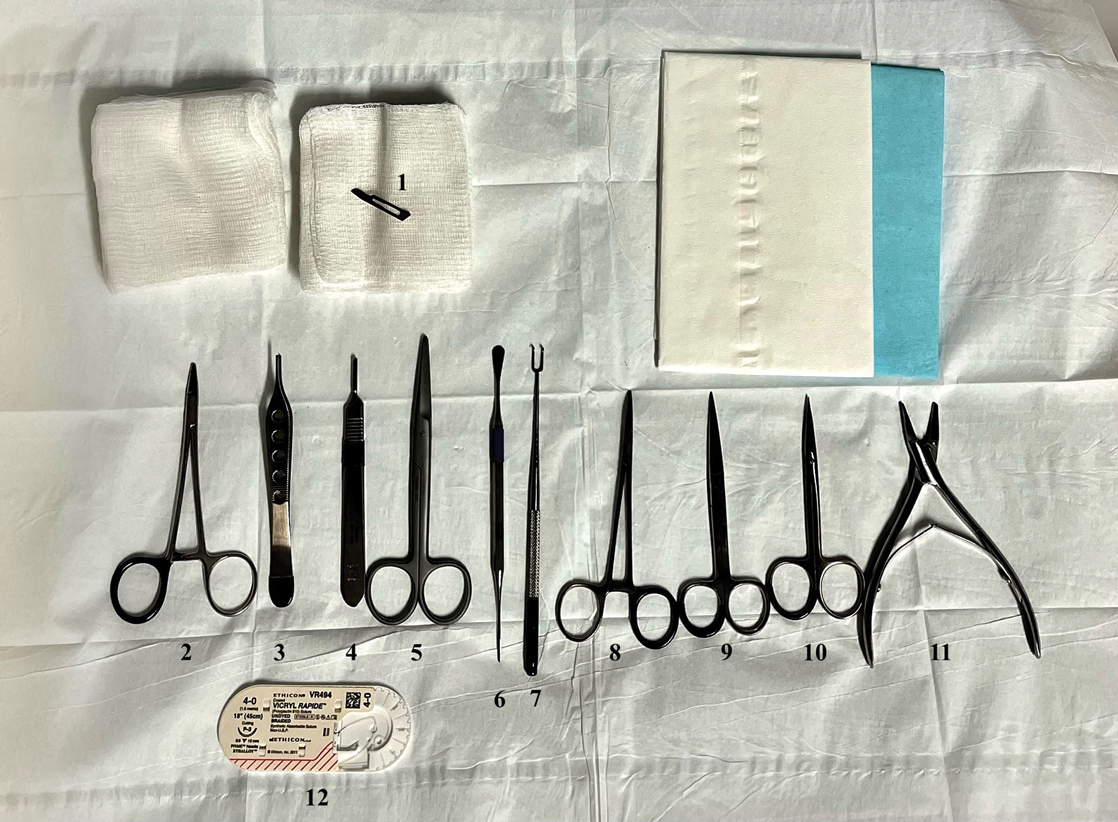

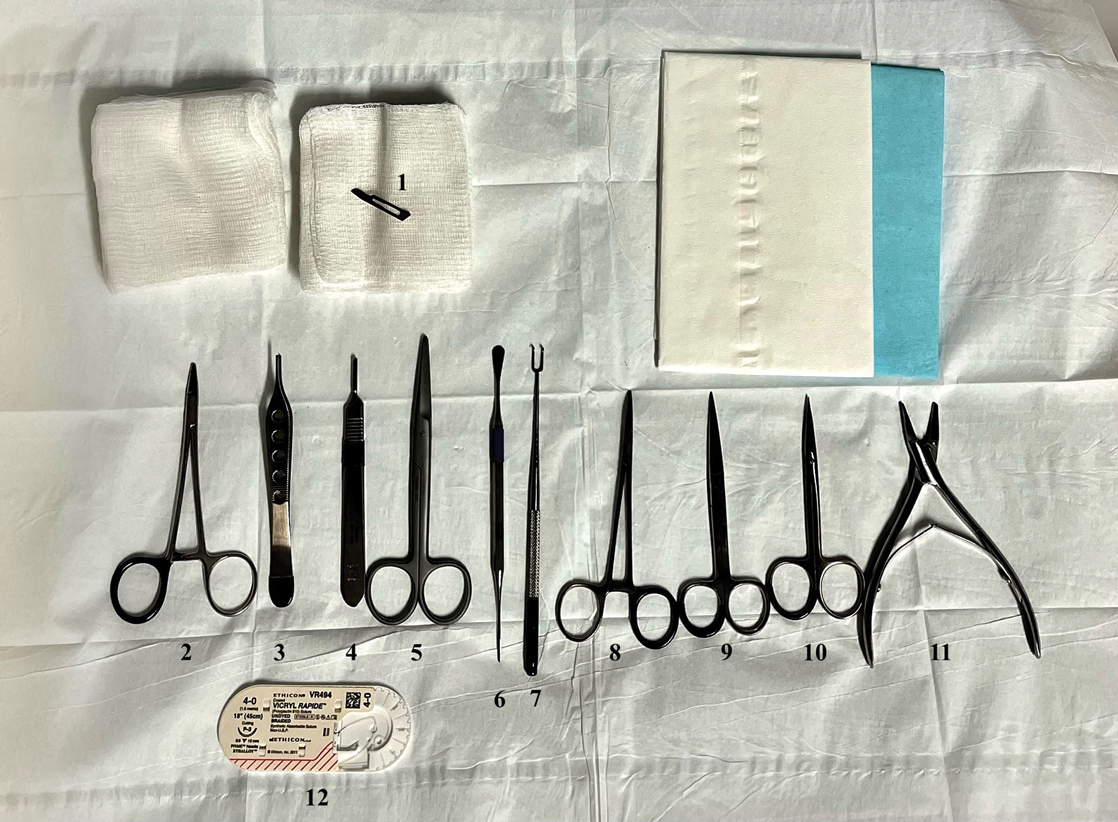

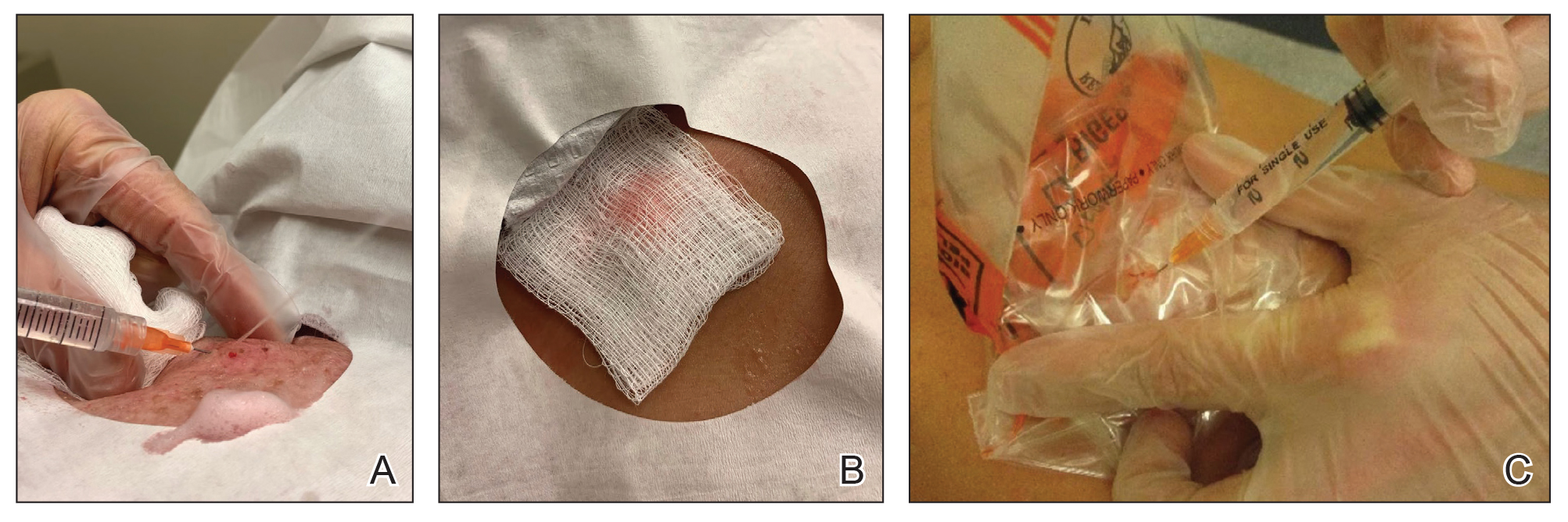

Some surgeons may experience pain that is refractory to stretching, potentially indicating the presence of MPS.3 Managing MPS via stretching alone may be a challenge. Physical therapists utilize various techniques to manually massage the tissue, but self-myofascial release—which involves the use of a tool such as a dense foam roller or massage ball, both of which can easily be purchased—may be convenient and effective for busy providers. To perform this technique, the operator lies with their back on a dense foam roller positioned perpendicular to the body and uses their legs to undulate or roll back and forth in a smooth motion (Figure 1). This may help to alleviate myofascial pain in the spinal intrinsic muscles, which often are prone to injury due to posture; it also warms the fascia and breaks up adhesions. Self-myofascial release may have similar acute analgesic effects to classic stretching while also helping to alleviate MPS.

Strengthening Exercises—Musculoskeletal injuries often begin with fatigue in postural stabilizing muscles of the trunk and shoulders, leading the dermatologist to assume a slouched posture. Dermatologists should perform strengthening exercises targeting the trunk and shoulder girdle, which help to promote good working posture while optimizing the function of the arms and hands. Ideally, dermatologists should incorporate strengthening exercises 3 to 4 times per week in combination with daily stretching.

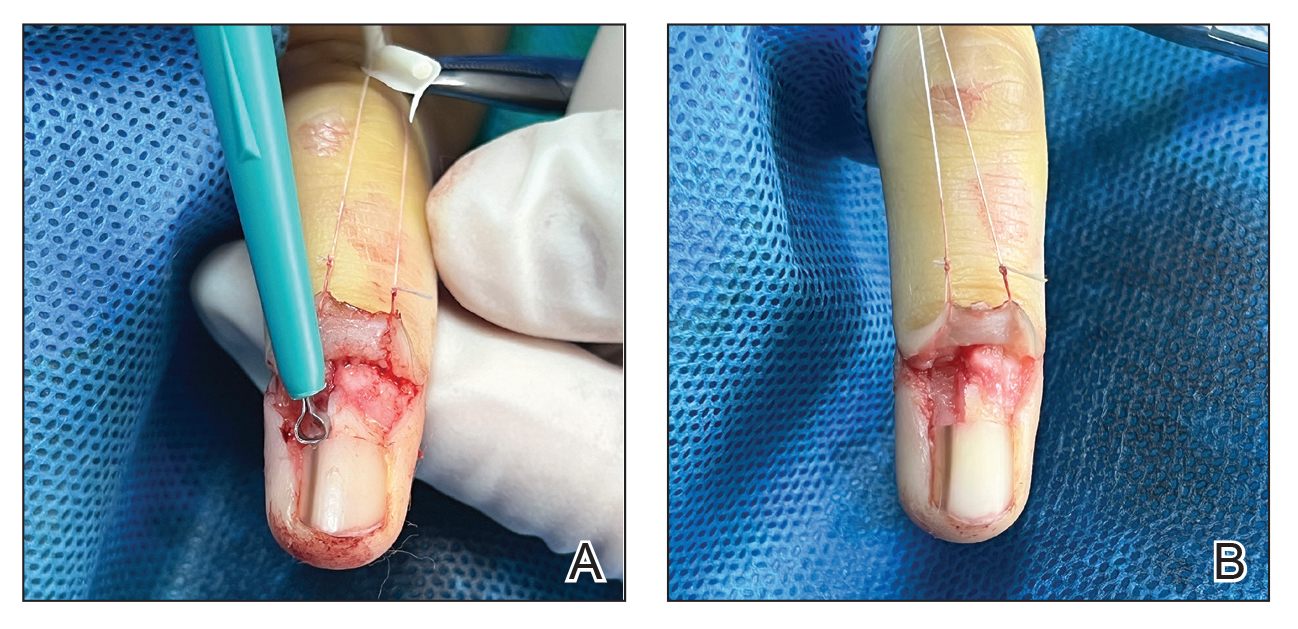

The 4-point kneeling alternate arm and leg extensions technique targets many muscle groups that commonly are affected in dermatologists and dermatologic surgeons. While on all fours, the operator positions the hands under the shoulders and the knees under the hips. The neck remains in line with the back with the eyes facing the floor. The abdominal muscles are then pulled up and in while simultaneously extending the left arm and right leg until both are parallel to the floor. This position should be held for 5 seconds and then repeated with the opposite contralateral extremities (Figure 2). Exercises specific to each muscle group also can be performed, such as planks to enhance truncal stability or scapular wall clocks to strengthen the shoulder girdle (eFigure 2). To perform scapular wall clocks, wrap a single resistance band around both wrists. Next, press the hands and elbows gently into a wall pointing superiorly and imagine there is a clock on the wall with 12 o’clock at the top and 6 o’clock at the bottom. Press the wrists outward on the band, keep the elbows straight, and reach out with the right hand while keeping the left hand stable. Move the right hand to the 1-, 3-, and 5-o’clock positions. Repeat with the left hand while holding the right hand stable. Move the left hand to the 11-, 9-, 7-, and 6-o’clock positions. Repeat these steps for 3 to 5 sets.

It is important to note that a decreased flow of oxygen and nutrients to muscles contributes to MSIs. Aerobic exercises increase blood flow and improve the ability of the muscles to utilize oxygen. Engaging in an enjoyable aerobic activity (eg, walking, running, swimming, cycling) 3 to 4 times per week can help prevent MSIs; however, as with any new exercise regimen (including the strengthening techniques described here), it is important to consult your primary care physician before getting started.

Practice Implications

As dermatologists progress in their careers, implementation of these techniques can mitigate MSIs and their sequelae. The long-term benefits of stretching, mobility, and strengthening exercises are dependent on having ergonomically suitable environmental factors. In addition to their own mechanics and posture, dermatologists must consider all elements that may affect the ergonomics of their daily practice, including operating room layout, instrumentation and workflow, and patient positioning. Through a consistent approach to prevention using the techniques described here, dermatologists can minimize the risk for MSIs and foster sustainability in their careers.

- Chan J, Kim DJ, Kassira-Carley S, et al. Ergonomics in dermatologic surgery: lessons learned across related specialties and opportunities for improvement. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:763-772. doi:10.1097 /DSS.0000000000002295

- Liang CA, Levine VJ, Dusza SW, et al. Musculoskeletal disorders and ergonomics in dermatologic surgery: a survey of Mohs surgeons in 2010. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:240-248. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02237.x

- Valachi B, Valachi K. Preventing musculoskeletal disorders in clinical dentistry: strategies to address the mechanisms leading to musculoskeletal disorders. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:1604-1612. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0106

- Carley SK, Strauss JD, Vidal NY. Ergonomic solutions for dermatologists. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7(5 part B):863-866. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.08.006

- da Costa BR, Vieira ER. Stretching to reduce work-related musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review. J Rehabil Med. 2008;40:321-328. doi:10.2340/16501977-0204

Practice Gap

Dermatology encompasses a wide range of procedures performed in both clinical and surgical settings. One comprehensive review of ergonomics in dermatologic surgery found a high prevalence of musculoskeletal injuries (MSIs).1 A survey conducted in 2010 revealed that 90% of dermatologic surgeons experienced MSIs, which commonly resulted in neck, shoulder, and/or back pain.2

Prolonged abnormal static postures and repetitive motions, which are common in dermatologic practice, can lead to muscle imbalances and focal muscular ischemia, increasing physicians’ susceptibility to MSIs. When muscle fibers experience enough repeated focal ischemia, they may enter a constant state of contraction leading to myofascial pain syndrome (MPS); these painful areas are known as trigger points and often are refractory to traditional stretching.3

Musculoskeletal injuries can potentially impact dermatologists’ career longevity and satisfaction. To date, the literature on techniques and exercises that may prevent or alleviate MSIs is limited.1,4 We collaborated with a colleague in physical therapy (R.P.) to present stretching, mobility, and strengthening techniques and exercises dermatologists can perform both in and outside the procedure room to potentially reduce pain and prevent future MSIs.

The Techniques

Stretching and Mobility Exercises—When dermatologists adopt abnormal static postures, they are at risk for muscular imbalances caused by repetitive flexion and/or rotation in one direction. Over time, these repetitive movements can result in loss of flexibility in the direction opposite to that in which they are consistently positioned.3 Regular stretching offers physiologic benefits such as maintaining joint range of motion, increasing blood flow to muscles, and increasing synovial fluid production—all of which contribute to reduced risk for MSIs.3 Multiple studies and a systematic review have found that regular stretching throughout the day serves as an effective method for preventing and mitigating MSI pain in health care providers.1,3-5

Considering the directional manner of MSIs induced by prolonged static positions, the most benefit will be derived from stretches or extension in the opposite direction of that in which the practitioner usually works. For most dermatologic surgeons, stretches should target the trapezius muscles, shoulders, and cervical musculature. Techniques such as the neck and shoulder combination stretch, the upper trapezius stretch, and the downward shoulder blade squeeze stretch can be performed regularly throughout the day.3,4 To perform the neck and shoulder combination stretch, place the arm in flexion to shoulder height and bend the elbow at a 90° angle. Gently pull the arm across the front of the body, point the head gazing in the direction of the shoulder being stretched, and hold for 10 to 20 seconds. Repeat with the other side (eFigure 1).

Some surgeons may experience pain that is refractory to stretching, potentially indicating the presence of MPS.3 Managing MPS via stretching alone may be a challenge. Physical therapists utilize various techniques to manually massage the tissue, but self-myofascial release—which involves the use of a tool such as a dense foam roller or massage ball, both of which can easily be purchased—may be convenient and effective for busy providers. To perform this technique, the operator lies with their back on a dense foam roller positioned perpendicular to the body and uses their legs to undulate or roll back and forth in a smooth motion (Figure 1). This may help to alleviate myofascial pain in the spinal intrinsic muscles, which often are prone to injury due to posture; it also warms the fascia and breaks up adhesions. Self-myofascial release may have similar acute analgesic effects to classic stretching while also helping to alleviate MPS.

Strengthening Exercises—Musculoskeletal injuries often begin with fatigue in postural stabilizing muscles of the trunk and shoulders, leading the dermatologist to assume a slouched posture. Dermatologists should perform strengthening exercises targeting the trunk and shoulder girdle, which help to promote good working posture while optimizing the function of the arms and hands. Ideally, dermatologists should incorporate strengthening exercises 3 to 4 times per week in combination with daily stretching.

The 4-point kneeling alternate arm and leg extensions technique targets many muscle groups that commonly are affected in dermatologists and dermatologic surgeons. While on all fours, the operator positions the hands under the shoulders and the knees under the hips. The neck remains in line with the back with the eyes facing the floor. The abdominal muscles are then pulled up and in while simultaneously extending the left arm and right leg until both are parallel to the floor. This position should be held for 5 seconds and then repeated with the opposite contralateral extremities (Figure 2). Exercises specific to each muscle group also can be performed, such as planks to enhance truncal stability or scapular wall clocks to strengthen the shoulder girdle (eFigure 2). To perform scapular wall clocks, wrap a single resistance band around both wrists. Next, press the hands and elbows gently into a wall pointing superiorly and imagine there is a clock on the wall with 12 o’clock at the top and 6 o’clock at the bottom. Press the wrists outward on the band, keep the elbows straight, and reach out with the right hand while keeping the left hand stable. Move the right hand to the 1-, 3-, and 5-o’clock positions. Repeat with the left hand while holding the right hand stable. Move the left hand to the 11-, 9-, 7-, and 6-o’clock positions. Repeat these steps for 3 to 5 sets.

It is important to note that a decreased flow of oxygen and nutrients to muscles contributes to MSIs. Aerobic exercises increase blood flow and improve the ability of the muscles to utilize oxygen. Engaging in an enjoyable aerobic activity (eg, walking, running, swimming, cycling) 3 to 4 times per week can help prevent MSIs; however, as with any new exercise regimen (including the strengthening techniques described here), it is important to consult your primary care physician before getting started.

Practice Implications

As dermatologists progress in their careers, implementation of these techniques can mitigate MSIs and their sequelae. The long-term benefits of stretching, mobility, and strengthening exercises are dependent on having ergonomically suitable environmental factors. In addition to their own mechanics and posture, dermatologists must consider all elements that may affect the ergonomics of their daily practice, including operating room layout, instrumentation and workflow, and patient positioning. Through a consistent approach to prevention using the techniques described here, dermatologists can minimize the risk for MSIs and foster sustainability in their careers.

Practice Gap

Dermatology encompasses a wide range of procedures performed in both clinical and surgical settings. One comprehensive review of ergonomics in dermatologic surgery found a high prevalence of musculoskeletal injuries (MSIs).1 A survey conducted in 2010 revealed that 90% of dermatologic surgeons experienced MSIs, which commonly resulted in neck, shoulder, and/or back pain.2

Prolonged abnormal static postures and repetitive motions, which are common in dermatologic practice, can lead to muscle imbalances and focal muscular ischemia, increasing physicians’ susceptibility to MSIs. When muscle fibers experience enough repeated focal ischemia, they may enter a constant state of contraction leading to myofascial pain syndrome (MPS); these painful areas are known as trigger points and often are refractory to traditional stretching.3

Musculoskeletal injuries can potentially impact dermatologists’ career longevity and satisfaction. To date, the literature on techniques and exercises that may prevent or alleviate MSIs is limited.1,4 We collaborated with a colleague in physical therapy (R.P.) to present stretching, mobility, and strengthening techniques and exercises dermatologists can perform both in and outside the procedure room to potentially reduce pain and prevent future MSIs.

The Techniques

Stretching and Mobility Exercises—When dermatologists adopt abnormal static postures, they are at risk for muscular imbalances caused by repetitive flexion and/or rotation in one direction. Over time, these repetitive movements can result in loss of flexibility in the direction opposite to that in which they are consistently positioned.3 Regular stretching offers physiologic benefits such as maintaining joint range of motion, increasing blood flow to muscles, and increasing synovial fluid production—all of which contribute to reduced risk for MSIs.3 Multiple studies and a systematic review have found that regular stretching throughout the day serves as an effective method for preventing and mitigating MSI pain in health care providers.1,3-5

Considering the directional manner of MSIs induced by prolonged static positions, the most benefit will be derived from stretches or extension in the opposite direction of that in which the practitioner usually works. For most dermatologic surgeons, stretches should target the trapezius muscles, shoulders, and cervical musculature. Techniques such as the neck and shoulder combination stretch, the upper trapezius stretch, and the downward shoulder blade squeeze stretch can be performed regularly throughout the day.3,4 To perform the neck and shoulder combination stretch, place the arm in flexion to shoulder height and bend the elbow at a 90° angle. Gently pull the arm across the front of the body, point the head gazing in the direction of the shoulder being stretched, and hold for 10 to 20 seconds. Repeat with the other side (eFigure 1).

Some surgeons may experience pain that is refractory to stretching, potentially indicating the presence of MPS.3 Managing MPS via stretching alone may be a challenge. Physical therapists utilize various techniques to manually massage the tissue, but self-myofascial release—which involves the use of a tool such as a dense foam roller or massage ball, both of which can easily be purchased—may be convenient and effective for busy providers. To perform this technique, the operator lies with their back on a dense foam roller positioned perpendicular to the body and uses their legs to undulate or roll back and forth in a smooth motion (Figure 1). This may help to alleviate myofascial pain in the spinal intrinsic muscles, which often are prone to injury due to posture; it also warms the fascia and breaks up adhesions. Self-myofascial release may have similar acute analgesic effects to classic stretching while also helping to alleviate MPS.

Strengthening Exercises—Musculoskeletal injuries often begin with fatigue in postural stabilizing muscles of the trunk and shoulders, leading the dermatologist to assume a slouched posture. Dermatologists should perform strengthening exercises targeting the trunk and shoulder girdle, which help to promote good working posture while optimizing the function of the arms and hands. Ideally, dermatologists should incorporate strengthening exercises 3 to 4 times per week in combination with daily stretching.

The 4-point kneeling alternate arm and leg extensions technique targets many muscle groups that commonly are affected in dermatologists and dermatologic surgeons. While on all fours, the operator positions the hands under the shoulders and the knees under the hips. The neck remains in line with the back with the eyes facing the floor. The abdominal muscles are then pulled up and in while simultaneously extending the left arm and right leg until both are parallel to the floor. This position should be held for 5 seconds and then repeated with the opposite contralateral extremities (Figure 2). Exercises specific to each muscle group also can be performed, such as planks to enhance truncal stability or scapular wall clocks to strengthen the shoulder girdle (eFigure 2). To perform scapular wall clocks, wrap a single resistance band around both wrists. Next, press the hands and elbows gently into a wall pointing superiorly and imagine there is a clock on the wall with 12 o’clock at the top and 6 o’clock at the bottom. Press the wrists outward on the band, keep the elbows straight, and reach out with the right hand while keeping the left hand stable. Move the right hand to the 1-, 3-, and 5-o’clock positions. Repeat with the left hand while holding the right hand stable. Move the left hand to the 11-, 9-, 7-, and 6-o’clock positions. Repeat these steps for 3 to 5 sets.

It is important to note that a decreased flow of oxygen and nutrients to muscles contributes to MSIs. Aerobic exercises increase blood flow and improve the ability of the muscles to utilize oxygen. Engaging in an enjoyable aerobic activity (eg, walking, running, swimming, cycling) 3 to 4 times per week can help prevent MSIs; however, as with any new exercise regimen (including the strengthening techniques described here), it is important to consult your primary care physician before getting started.

Practice Implications

As dermatologists progress in their careers, implementation of these techniques can mitigate MSIs and their sequelae. The long-term benefits of stretching, mobility, and strengthening exercises are dependent on having ergonomically suitable environmental factors. In addition to their own mechanics and posture, dermatologists must consider all elements that may affect the ergonomics of their daily practice, including operating room layout, instrumentation and workflow, and patient positioning. Through a consistent approach to prevention using the techniques described here, dermatologists can minimize the risk for MSIs and foster sustainability in their careers.

- Chan J, Kim DJ, Kassira-Carley S, et al. Ergonomics in dermatologic surgery: lessons learned across related specialties and opportunities for improvement. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:763-772. doi:10.1097 /DSS.0000000000002295

- Liang CA, Levine VJ, Dusza SW, et al. Musculoskeletal disorders and ergonomics in dermatologic surgery: a survey of Mohs surgeons in 2010. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:240-248. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02237.x

- Valachi B, Valachi K. Preventing musculoskeletal disorders in clinical dentistry: strategies to address the mechanisms leading to musculoskeletal disorders. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:1604-1612. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0106

- Carley SK, Strauss JD, Vidal NY. Ergonomic solutions for dermatologists. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7(5 part B):863-866. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.08.006

- da Costa BR, Vieira ER. Stretching to reduce work-related musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review. J Rehabil Med. 2008;40:321-328. doi:10.2340/16501977-0204

- Chan J, Kim DJ, Kassira-Carley S, et al. Ergonomics in dermatologic surgery: lessons learned across related specialties and opportunities for improvement. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:763-772. doi:10.1097 /DSS.0000000000002295

- Liang CA, Levine VJ, Dusza SW, et al. Musculoskeletal disorders and ergonomics in dermatologic surgery: a survey of Mohs surgeons in 2010. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:240-248. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02237.x

- Valachi B, Valachi K. Preventing musculoskeletal disorders in clinical dentistry: strategies to address the mechanisms leading to musculoskeletal disorders. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:1604-1612. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0106

- Carley SK, Strauss JD, Vidal NY. Ergonomic solutions for dermatologists. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7(5 part B):863-866. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.08.006

- da Costa BR, Vieira ER. Stretching to reduce work-related musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review. J Rehabil Med. 2008;40:321-328. doi:10.2340/16501977-0204

Ergonomics in Dermatologic Procedures: Mobility Exercises to Incorporate In and Out of the Office

Ergonomics in Dermatologic Procedures: Mobility Exercises to Incorporate In and Out of the Office

Best Practices for Capturing Clinical and Dermoscopic Images With Smartphone Photography

Best Practices for Capturing Clinical and Dermoscopic Images With Smartphone Photography

PRACTICE GAP

Photography is an essential tool in modern dermatologic practice, aiding in the evaluation, documentation, and monitoring of nevi, skin cancers, and other cutaneous pathologies.1 With the rapid technologic advancement of smartphone cameras, high-quality clinical and dermoscopic images have become increasingly easy to attain; however, best practices for optimizing smartphone photography are limited in the medical literature. We have collated a series of recommendations to help fill this knowledge gap.

A search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE was conducted using the terms clinical imaging AND smartphone, clinical photography AND smartphone, dermatology AND photography, dermatology AND imaging, dermoscopy AND photography, and dermoscopy AND imaging. We also consulted with Elizabeth Seiverling, MD (Annville, Pennsylvania) and Jennifer Stein, MD (New York, New York)—both renowned experts in the fields of dermatology, dermoscopy, and medical photography—via email and video meetings conducted during the period from June 1, 2022, through August 20, 2022. Our goal in creating this guide is to facilitate standardized yet simple ways to integrate smartphone photography into current dermatologic practice.

THE TECHNIQUE

Clinical Photography

Clinical images should be captured in a space with ample indirect natural light, such as a patient examination room with frosted or draped windows, ensuring patient privacy is maintained.1,2 The smartphone’s flash can be used if natural lighting is insufficient, but caution should be exercised when photographing patients with darker skin types, as the flash may create an undesired glare. To combat this, consider using a small clip-on light-emitting diode ring light positioned at a 45° angle for more uniform lighting and reduced glare (eFigures 1 and 2).2 This additional light source helps to distribute light evenly across the patient’s skin, enhancing detail visibility, minimizing harsh shadows, and ensuring a more accurate representation of skin pigmentation.2

When a magnified image is required (eg, to capture suspicious lesions with unique and detailed findings such as irregular borders or atypical pigmentation), use the smartphone’s digital zoom function rather than physically moving the camera lens closer to the subject. Moving the camera too close can cause proximity distortion, artificially enlarging objects close to the lens and degrading the quality of the image.1,2 Unnecessary camera features such as portrait mode, live focus, and filters should be turned off to maintain image accuracy. It also is important to avoid excessive manual adjustments to exposure and brightness settings.1,2 The tap-to-focus feature that is integrated into many smartphone cameras can be utilized to ensure the capture of sharp, focused images. After verifying the image preview on the smartphone display, take the photograph. Immediately review the captured image to ensure it is clear and well lit and accurately depicts the area of interest, including its color, texture, and any relevant details, without glare or distortion. If the image does not meet these criteria, promptly reattempt to achieve the desired quality.

Dermoscopic Photography

Dermoscopy, which enables magnified examination of skin lesions, is increasingly being utilized in dermatology. While traditional dermoscopic photography requires specialized equipment, such as large single-lens reflex cameras with dedicated dermoscopic lens attachments, smartphone cameras now can be used to obtain dermoscopic images of reasonable quality.3,4 Adhering to specific practices can help to optimize the quality of dermoscopic images obtained via this technique.

Before capturing an image, it is essential to prepare both the lesion and the surrounding skin. Ensure the area is cleaned thoroughly and trim any hairs that may obscure the image. Apply an interface fluid such as rubbing alcohol or ultrasonography gel to improve image clarity by reducing surface tension and reflections, minimizing glare, and ensuring even light transmission throughout the lesion.5 As recommended for clinical photography, images should be captured in a space with ample indirect light. For best results, we recommend utilizing the primary photo capture option instead of portrait or panoramic mode or additional settings. It is crucial to disable features such as live focus, filters, night mode, and flash, as they may alter image accuracy; however, use of the tap-to-focus feature or manual settings adjustment is encouraged to ensure a high-resolution photograph.

Once these smartphone settings have been verified, position the dermatoscope directly over the lesion of interest. Next, place the smartphone camera lens directly against the eyepiece of the dermatoscope (Figure). Center the lesion in the field of view on the screen. Most smartphones enable adjustment to the image magnification on the photo capture screen. A single tap on the screen should populate the zoom options (eg, ×0.5, ×1, ×3) and allow for adjustment. For the majority of dermoscopic photographs, we recommend standard ×1 magnification, as it typically provides a clear and accurate representation of the lesion without introducing the possibility of image distortion. To obtain a close-up image, use the smartphone’s digital zoom function prior to taking the photograph rather than zooming in on the image after it has been captured; however, to minimize proximity distortion and maintain optimal image quality, avoid exceeding the halfway point on the camera’s zoom dial. After verifying the image preview on the smartphone display, capture the photograph. Immediate review is recommended to allow for prompt reattempt at capturing the image if needed.

PRACTICE IMPLICATIONS

The inherent convenience and accessibility offered by smartphone photography further solidifies its status as a valuable tool in modern dermatologic practice. By adhering to the best practices outlined in this guide, dermatologists can utilize smartphones to capture high-quality clinical and dermoscopic images that support accurate diagnosis and enhance patient care. This approach helps streamline workflows, enhance consistency in image quality, and standardize image capture across different settings and providers.

Additionally, smartphone photography can enhance both education and telemedicine by enabling physicians to easily share high-quality images with colleagues for virtual consultations, second opinions, and collaborative diagnoses. This sharing of images fosters learning opportunities, supports knowledge exchange, and allows for real-time feedback—all of which can improve clinical decision-making. Moreover, it broadens access to dermatologic expertise, strengthens communication between health care providers, and facilitates timely decision-making. As a result, patients benefit from more efficient, accurate, and collaborative care.

- Muraco L. Improved medical photography: key tips for creating images of lasting value. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:121-123. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2019.3849

- Alvarado SM, Flessland P, Grant-Kels JM, et al. Practical strategies for improving clinical photography of dark skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:E21-E23. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.09.001

- Pagliarello C, Feliciani C, Fantini C, et al. Use of the dermoscope as a smartphone close-up lens and LED annular macro ring flash. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:E27–E28. doi:10.1016/j.jaad .2015.12.04

- Zuo KJ, Guo D, Rao J. Mobile teledermatology: a promising future in clinical practice. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:387-391. doi:10.2310/7750.2013.13030

- Gewirtzman AJ, Saurat J-H, Braun RP. An evaluation of dermscopy fluids and application techniques. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:59-63. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05366.x

PRACTICE GAP

Photography is an essential tool in modern dermatologic practice, aiding in the evaluation, documentation, and monitoring of nevi, skin cancers, and other cutaneous pathologies.1 With the rapid technologic advancement of smartphone cameras, high-quality clinical and dermoscopic images have become increasingly easy to attain; however, best practices for optimizing smartphone photography are limited in the medical literature. We have collated a series of recommendations to help fill this knowledge gap.

A search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE was conducted using the terms clinical imaging AND smartphone, clinical photography AND smartphone, dermatology AND photography, dermatology AND imaging, dermoscopy AND photography, and dermoscopy AND imaging. We also consulted with Elizabeth Seiverling, MD (Annville, Pennsylvania) and Jennifer Stein, MD (New York, New York)—both renowned experts in the fields of dermatology, dermoscopy, and medical photography—via email and video meetings conducted during the period from June 1, 2022, through August 20, 2022. Our goal in creating this guide is to facilitate standardized yet simple ways to integrate smartphone photography into current dermatologic practice.

THE TECHNIQUE

Clinical Photography

Clinical images should be captured in a space with ample indirect natural light, such as a patient examination room with frosted or draped windows, ensuring patient privacy is maintained.1,2 The smartphone’s flash can be used if natural lighting is insufficient, but caution should be exercised when photographing patients with darker skin types, as the flash may create an undesired glare. To combat this, consider using a small clip-on light-emitting diode ring light positioned at a 45° angle for more uniform lighting and reduced glare (eFigures 1 and 2).2 This additional light source helps to distribute light evenly across the patient’s skin, enhancing detail visibility, minimizing harsh shadows, and ensuring a more accurate representation of skin pigmentation.2

When a magnified image is required (eg, to capture suspicious lesions with unique and detailed findings such as irregular borders or atypical pigmentation), use the smartphone’s digital zoom function rather than physically moving the camera lens closer to the subject. Moving the camera too close can cause proximity distortion, artificially enlarging objects close to the lens and degrading the quality of the image.1,2 Unnecessary camera features such as portrait mode, live focus, and filters should be turned off to maintain image accuracy. It also is important to avoid excessive manual adjustments to exposure and brightness settings.1,2 The tap-to-focus feature that is integrated into many smartphone cameras can be utilized to ensure the capture of sharp, focused images. After verifying the image preview on the smartphone display, take the photograph. Immediately review the captured image to ensure it is clear and well lit and accurately depicts the area of interest, including its color, texture, and any relevant details, without glare or distortion. If the image does not meet these criteria, promptly reattempt to achieve the desired quality.

Dermoscopic Photography

Dermoscopy, which enables magnified examination of skin lesions, is increasingly being utilized in dermatology. While traditional dermoscopic photography requires specialized equipment, such as large single-lens reflex cameras with dedicated dermoscopic lens attachments, smartphone cameras now can be used to obtain dermoscopic images of reasonable quality.3,4 Adhering to specific practices can help to optimize the quality of dermoscopic images obtained via this technique.

Before capturing an image, it is essential to prepare both the lesion and the surrounding skin. Ensure the area is cleaned thoroughly and trim any hairs that may obscure the image. Apply an interface fluid such as rubbing alcohol or ultrasonography gel to improve image clarity by reducing surface tension and reflections, minimizing glare, and ensuring even light transmission throughout the lesion.5 As recommended for clinical photography, images should be captured in a space with ample indirect light. For best results, we recommend utilizing the primary photo capture option instead of portrait or panoramic mode or additional settings. It is crucial to disable features such as live focus, filters, night mode, and flash, as they may alter image accuracy; however, use of the tap-to-focus feature or manual settings adjustment is encouraged to ensure a high-resolution photograph.

Once these smartphone settings have been verified, position the dermatoscope directly over the lesion of interest. Next, place the smartphone camera lens directly against the eyepiece of the dermatoscope (Figure). Center the lesion in the field of view on the screen. Most smartphones enable adjustment to the image magnification on the photo capture screen. A single tap on the screen should populate the zoom options (eg, ×0.5, ×1, ×3) and allow for adjustment. For the majority of dermoscopic photographs, we recommend standard ×1 magnification, as it typically provides a clear and accurate representation of the lesion without introducing the possibility of image distortion. To obtain a close-up image, use the smartphone’s digital zoom function prior to taking the photograph rather than zooming in on the image after it has been captured; however, to minimize proximity distortion and maintain optimal image quality, avoid exceeding the halfway point on the camera’s zoom dial. After verifying the image preview on the smartphone display, capture the photograph. Immediate review is recommended to allow for prompt reattempt at capturing the image if needed.

PRACTICE IMPLICATIONS

The inherent convenience and accessibility offered by smartphone photography further solidifies its status as a valuable tool in modern dermatologic practice. By adhering to the best practices outlined in this guide, dermatologists can utilize smartphones to capture high-quality clinical and dermoscopic images that support accurate diagnosis and enhance patient care. This approach helps streamline workflows, enhance consistency in image quality, and standardize image capture across different settings and providers.

Additionally, smartphone photography can enhance both education and telemedicine by enabling physicians to easily share high-quality images with colleagues for virtual consultations, second opinions, and collaborative diagnoses. This sharing of images fosters learning opportunities, supports knowledge exchange, and allows for real-time feedback—all of which can improve clinical decision-making. Moreover, it broadens access to dermatologic expertise, strengthens communication between health care providers, and facilitates timely decision-making. As a result, patients benefit from more efficient, accurate, and collaborative care.

PRACTICE GAP

Photography is an essential tool in modern dermatologic practice, aiding in the evaluation, documentation, and monitoring of nevi, skin cancers, and other cutaneous pathologies.1 With the rapid technologic advancement of smartphone cameras, high-quality clinical and dermoscopic images have become increasingly easy to attain; however, best practices for optimizing smartphone photography are limited in the medical literature. We have collated a series of recommendations to help fill this knowledge gap.

A search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE was conducted using the terms clinical imaging AND smartphone, clinical photography AND smartphone, dermatology AND photography, dermatology AND imaging, dermoscopy AND photography, and dermoscopy AND imaging. We also consulted with Elizabeth Seiverling, MD (Annville, Pennsylvania) and Jennifer Stein, MD (New York, New York)—both renowned experts in the fields of dermatology, dermoscopy, and medical photography—via email and video meetings conducted during the period from June 1, 2022, through August 20, 2022. Our goal in creating this guide is to facilitate standardized yet simple ways to integrate smartphone photography into current dermatologic practice.

THE TECHNIQUE

Clinical Photography

Clinical images should be captured in a space with ample indirect natural light, such as a patient examination room with frosted or draped windows, ensuring patient privacy is maintained.1,2 The smartphone’s flash can be used if natural lighting is insufficient, but caution should be exercised when photographing patients with darker skin types, as the flash may create an undesired glare. To combat this, consider using a small clip-on light-emitting diode ring light positioned at a 45° angle for more uniform lighting and reduced glare (eFigures 1 and 2).2 This additional light source helps to distribute light evenly across the patient’s skin, enhancing detail visibility, minimizing harsh shadows, and ensuring a more accurate representation of skin pigmentation.2

When a magnified image is required (eg, to capture suspicious lesions with unique and detailed findings such as irregular borders or atypical pigmentation), use the smartphone’s digital zoom function rather than physically moving the camera lens closer to the subject. Moving the camera too close can cause proximity distortion, artificially enlarging objects close to the lens and degrading the quality of the image.1,2 Unnecessary camera features such as portrait mode, live focus, and filters should be turned off to maintain image accuracy. It also is important to avoid excessive manual adjustments to exposure and brightness settings.1,2 The tap-to-focus feature that is integrated into many smartphone cameras can be utilized to ensure the capture of sharp, focused images. After verifying the image preview on the smartphone display, take the photograph. Immediately review the captured image to ensure it is clear and well lit and accurately depicts the area of interest, including its color, texture, and any relevant details, without glare or distortion. If the image does not meet these criteria, promptly reattempt to achieve the desired quality.

Dermoscopic Photography

Dermoscopy, which enables magnified examination of skin lesions, is increasingly being utilized in dermatology. While traditional dermoscopic photography requires specialized equipment, such as large single-lens reflex cameras with dedicated dermoscopic lens attachments, smartphone cameras now can be used to obtain dermoscopic images of reasonable quality.3,4 Adhering to specific practices can help to optimize the quality of dermoscopic images obtained via this technique.