User login

‘So You Have an Idea…’: A Practical Guide to Tech and Device Development for the Early Career GI

You are in the middle of a busy clinic day and think, “there has to be a better way to do this.” Suddenly, a better way to do something becomes obvious. Maybe it’s a tool that simplifies documentation, a device that improves patient comfort, or an app that bridges a clinical gap. Many physicians, especially early career gastroenterologists, have ideas like this, but few know what to do next.

This article is for the curious innovator at the beginning of their clinical career. It offers practical, real-world guidance on developing a clinical product: whether that be hardware, software, or a hybrid. It outlines what questions to ask, who to consult, and how to protect your work, using personal insights and business principles learned through lived experience.

1. Understand Intellectual Property (IP): Know Its Value and Ownership

What is IP?

Intellectual property refers to your original creations: inventions, designs, software, and more. This is what you want to protect legally through patents, trademarks, or copyrights.

Who owns your idea?

This is the first and most important question to ask. If you are employed (especially by a hospital or academic center), your contract may already give your employer rights to any inventions you create, even those developed in your personal time.

What to ask:

- Does my employment contract include an “assignment of inventions” clause?

- Does the institution claim rights to anything developed with institutional resources?

- Are there moonlighting or external activity policies that affect this?

If you are developing an idea on your personal time, with your own resources, and outside your scope of clinical duties, it might still be considered “theirs” under some contracts. Early legal consultation is critical. A specialized IP attorney can help you understand what you own and how to protect it. This should be done early, ideally before you start building anything.

2. Lawyers Aren’t Optional: They’re Essential Early Partners

You do not need a full legal team, but you do need a lawyer early. An early consultation with an IP attorney can clarify your rights, guide your filing process (e.g. provisional patents), and help you avoid costly missteps.

Do this before sharing your idea publicly, including in academic presentations, pitch competitions, or even on social media. Public disclosure can start a clock ticking for application to protect your IP.

3. Build a Founding Team with Intent

Think of your startup team like a long-term relationship: you’re committing to build something together through uncertainty, tension, and change.

Strong early-stage teams often include:

- The Visionary – understands the clinical need and vision

- The Builder – engineer, developer, or designer

- The Doer – project manager or operations lead

Before forming a company, clearly define:

- Ownership (equity percentages)

- Roles and responsibilities

- Time commitments

- What happens if someone exits

Have these discussions early and document your agreements. Avoid informal “handshake” deals that can lead to serious disputes later.

4. You Don’t Need to Know Everything on Day One

You do not need to know how to write code, build a prototype, or get FDA clearance on day one. Successful innovators are humble learners. Use a Minimum Viable Product (MVP), a simple, functional version of your idea, to test assumptions and gather feedback. Iterate based on what you learn. Do not chase perfection; pursue progress. Consider using online accelerators like Y Combinator’s startup school or AGA’s Center for GI Innovation and Technology.

5. Incubators: Use them Strategically

Incubators can offer mentorship, seed funding, legal support, and technical resources, but they vary widely in value (see Table 1). Many may want equity, and not all offer when you truly need.

Ask Yourself:

- Do I need technical help, business mentorship, or just accountability?

- What does this incubator offer in terms of IP protection, exposure, and connections?

- Do I understand the equity trade-off?

- What services and funding do they provide?

- Do they take equity? How much and when?

- What’s their track record with similar ventures?

- Are their incentives aligned with your vision?

6. Academic Institutions: Partners or Pitfalls?

Universities can provide credibility, resources, and early funding through their tech transfer office (TTO).

Key Questions to Ask:

- Will my IP be managed by the TTO?

- How much say do I have in licensing decisions?

- Are there royalty-sharing agreements in place?

- Can I form a startup while employed here?

You may need to negotiate if you want to commercialize your idea independently.

7. Do it for Purpose, Not Payday

Most founders end up owning only a small percentage of their company by the time a product reaches the market. Do not expect to get rich. Do it because it solves a problem you care about. If it happens to come with a nice paycheck, then that is an added bonus.

Your clinical training and insight give you a unique edge. You already know what’s broken. Use that as your compass.

Conclusion

Innovation isn’t about brilliance, it’s about curiosity, structure, and tenacity (see Table 2). Start small. Protect your work. Choose the right partners. Most importantly, stay anchored in your mission to make GI care better.

Dr. Muratore is based at UNC Rex Digestive Health, Raleigh, North Carolina. She has no conflicts related to this article. Dr. Wechsler is based at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. She holds a patent assigned to Trustees of Dartmouth College. Dr. Shah is based at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan. He consults for Ardelyx, Laborie, Neuraxis, Salix, Sanofi, and Takeda and holds a patent with the Regents of the University of Michigan.

You are in the middle of a busy clinic day and think, “there has to be a better way to do this.” Suddenly, a better way to do something becomes obvious. Maybe it’s a tool that simplifies documentation, a device that improves patient comfort, or an app that bridges a clinical gap. Many physicians, especially early career gastroenterologists, have ideas like this, but few know what to do next.

This article is for the curious innovator at the beginning of their clinical career. It offers practical, real-world guidance on developing a clinical product: whether that be hardware, software, or a hybrid. It outlines what questions to ask, who to consult, and how to protect your work, using personal insights and business principles learned through lived experience.

1. Understand Intellectual Property (IP): Know Its Value and Ownership

What is IP?

Intellectual property refers to your original creations: inventions, designs, software, and more. This is what you want to protect legally through patents, trademarks, or copyrights.

Who owns your idea?

This is the first and most important question to ask. If you are employed (especially by a hospital or academic center), your contract may already give your employer rights to any inventions you create, even those developed in your personal time.

What to ask:

- Does my employment contract include an “assignment of inventions” clause?

- Does the institution claim rights to anything developed with institutional resources?

- Are there moonlighting or external activity policies that affect this?

If you are developing an idea on your personal time, with your own resources, and outside your scope of clinical duties, it might still be considered “theirs” under some contracts. Early legal consultation is critical. A specialized IP attorney can help you understand what you own and how to protect it. This should be done early, ideally before you start building anything.

2. Lawyers Aren’t Optional: They’re Essential Early Partners

You do not need a full legal team, but you do need a lawyer early. An early consultation with an IP attorney can clarify your rights, guide your filing process (e.g. provisional patents), and help you avoid costly missteps.

Do this before sharing your idea publicly, including in academic presentations, pitch competitions, or even on social media. Public disclosure can start a clock ticking for application to protect your IP.

3. Build a Founding Team with Intent

Think of your startup team like a long-term relationship: you’re committing to build something together through uncertainty, tension, and change.

Strong early-stage teams often include:

- The Visionary – understands the clinical need and vision

- The Builder – engineer, developer, or designer

- The Doer – project manager or operations lead

Before forming a company, clearly define:

- Ownership (equity percentages)

- Roles and responsibilities

- Time commitments

- What happens if someone exits

Have these discussions early and document your agreements. Avoid informal “handshake” deals that can lead to serious disputes later.

4. You Don’t Need to Know Everything on Day One

You do not need to know how to write code, build a prototype, or get FDA clearance on day one. Successful innovators are humble learners. Use a Minimum Viable Product (MVP), a simple, functional version of your idea, to test assumptions and gather feedback. Iterate based on what you learn. Do not chase perfection; pursue progress. Consider using online accelerators like Y Combinator’s startup school or AGA’s Center for GI Innovation and Technology.

5. Incubators: Use them Strategically

Incubators can offer mentorship, seed funding, legal support, and technical resources, but they vary widely in value (see Table 1). Many may want equity, and not all offer when you truly need.

Ask Yourself:

- Do I need technical help, business mentorship, or just accountability?

- What does this incubator offer in terms of IP protection, exposure, and connections?

- Do I understand the equity trade-off?

- What services and funding do they provide?

- Do they take equity? How much and when?

- What’s their track record with similar ventures?

- Are their incentives aligned with your vision?

6. Academic Institutions: Partners or Pitfalls?

Universities can provide credibility, resources, and early funding through their tech transfer office (TTO).

Key Questions to Ask:

- Will my IP be managed by the TTO?

- How much say do I have in licensing decisions?

- Are there royalty-sharing agreements in place?

- Can I form a startup while employed here?

You may need to negotiate if you want to commercialize your idea independently.

7. Do it for Purpose, Not Payday

Most founders end up owning only a small percentage of their company by the time a product reaches the market. Do not expect to get rich. Do it because it solves a problem you care about. If it happens to come with a nice paycheck, then that is an added bonus.

Your clinical training and insight give you a unique edge. You already know what’s broken. Use that as your compass.

Conclusion

Innovation isn’t about brilliance, it’s about curiosity, structure, and tenacity (see Table 2). Start small. Protect your work. Choose the right partners. Most importantly, stay anchored in your mission to make GI care better.

Dr. Muratore is based at UNC Rex Digestive Health, Raleigh, North Carolina. She has no conflicts related to this article. Dr. Wechsler is based at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. She holds a patent assigned to Trustees of Dartmouth College. Dr. Shah is based at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan. He consults for Ardelyx, Laborie, Neuraxis, Salix, Sanofi, and Takeda and holds a patent with the Regents of the University of Michigan.

You are in the middle of a busy clinic day and think, “there has to be a better way to do this.” Suddenly, a better way to do something becomes obvious. Maybe it’s a tool that simplifies documentation, a device that improves patient comfort, or an app that bridges a clinical gap. Many physicians, especially early career gastroenterologists, have ideas like this, but few know what to do next.

This article is for the curious innovator at the beginning of their clinical career. It offers practical, real-world guidance on developing a clinical product: whether that be hardware, software, or a hybrid. It outlines what questions to ask, who to consult, and how to protect your work, using personal insights and business principles learned through lived experience.

1. Understand Intellectual Property (IP): Know Its Value and Ownership

What is IP?

Intellectual property refers to your original creations: inventions, designs, software, and more. This is what you want to protect legally through patents, trademarks, or copyrights.

Who owns your idea?

This is the first and most important question to ask. If you are employed (especially by a hospital or academic center), your contract may already give your employer rights to any inventions you create, even those developed in your personal time.

What to ask:

- Does my employment contract include an “assignment of inventions” clause?

- Does the institution claim rights to anything developed with institutional resources?

- Are there moonlighting or external activity policies that affect this?

If you are developing an idea on your personal time, with your own resources, and outside your scope of clinical duties, it might still be considered “theirs” under some contracts. Early legal consultation is critical. A specialized IP attorney can help you understand what you own and how to protect it. This should be done early, ideally before you start building anything.

2. Lawyers Aren’t Optional: They’re Essential Early Partners

You do not need a full legal team, but you do need a lawyer early. An early consultation with an IP attorney can clarify your rights, guide your filing process (e.g. provisional patents), and help you avoid costly missteps.

Do this before sharing your idea publicly, including in academic presentations, pitch competitions, or even on social media. Public disclosure can start a clock ticking for application to protect your IP.

3. Build a Founding Team with Intent

Think of your startup team like a long-term relationship: you’re committing to build something together through uncertainty, tension, and change.

Strong early-stage teams often include:

- The Visionary – understands the clinical need and vision

- The Builder – engineer, developer, or designer

- The Doer – project manager or operations lead

Before forming a company, clearly define:

- Ownership (equity percentages)

- Roles and responsibilities

- Time commitments

- What happens if someone exits

Have these discussions early and document your agreements. Avoid informal “handshake” deals that can lead to serious disputes later.

4. You Don’t Need to Know Everything on Day One

You do not need to know how to write code, build a prototype, or get FDA clearance on day one. Successful innovators are humble learners. Use a Minimum Viable Product (MVP), a simple, functional version of your idea, to test assumptions and gather feedback. Iterate based on what you learn. Do not chase perfection; pursue progress. Consider using online accelerators like Y Combinator’s startup school or AGA’s Center for GI Innovation and Technology.

5. Incubators: Use them Strategically

Incubators can offer mentorship, seed funding, legal support, and technical resources, but they vary widely in value (see Table 1). Many may want equity, and not all offer when you truly need.

Ask Yourself:

- Do I need technical help, business mentorship, or just accountability?

- What does this incubator offer in terms of IP protection, exposure, and connections?

- Do I understand the equity trade-off?

- What services and funding do they provide?

- Do they take equity? How much and when?

- What’s their track record with similar ventures?

- Are their incentives aligned with your vision?

6. Academic Institutions: Partners or Pitfalls?

Universities can provide credibility, resources, and early funding through their tech transfer office (TTO).

Key Questions to Ask:

- Will my IP be managed by the TTO?

- How much say do I have in licensing decisions?

- Are there royalty-sharing agreements in place?

- Can I form a startup while employed here?

You may need to negotiate if you want to commercialize your idea independently.

7. Do it for Purpose, Not Payday

Most founders end up owning only a small percentage of their company by the time a product reaches the market. Do not expect to get rich. Do it because it solves a problem you care about. If it happens to come with a nice paycheck, then that is an added bonus.

Your clinical training and insight give you a unique edge. You already know what’s broken. Use that as your compass.

Conclusion

Innovation isn’t about brilliance, it’s about curiosity, structure, and tenacity (see Table 2). Start small. Protect your work. Choose the right partners. Most importantly, stay anchored in your mission to make GI care better.

Dr. Muratore is based at UNC Rex Digestive Health, Raleigh, North Carolina. She has no conflicts related to this article. Dr. Wechsler is based at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. She holds a patent assigned to Trustees of Dartmouth College. Dr. Shah is based at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan. He consults for Ardelyx, Laborie, Neuraxis, Salix, Sanofi, and Takeda and holds a patent with the Regents of the University of Michigan.

When Your First Job Isn’t Forever: Lessons from My Journey and What Early-Career GIs Need to Know

Introduction

For many of us in gastroenterology, landing that first attending job feels like the ultimate victory lap — the reward for all those years of training. We sign the contract, relocate, and imagine this will be our “forever job.” Reality often plays out differently.

In fact, 43% of physicians change jobs within five years, while 83% changed employers at least once in their careers.1 Even within our field — which is always in demand — turnover is high; 1 in 3 gastroenterologists are planning to leave their current role within two years.2 Why does this happen? More importantly, how do we navigate this transition with clarity and confidence as an early-career GI?

My Story: When I Dared to Change My “Forever Job”

When I signed my first attending contract, I didn’t negotiate a single thing. My priorities were simple: family in Toronto and visa requirements. After a decade of medical school, residency, and fellowship, everything else felt secondary. I was happy to be back home.

The job itself was good — reasonable hours, flexible colleagues, and ample opportunity to enhance my procedural skills. As I started carving out my niche in endobariatrics, the support I needed to grow further was not there. I kept telling myself that this job fulfilled my values and I needed to be patient: “this is my forever job. I am close to my family and that’s what matters.”

Then, during a suturing course at the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, I had a casual chat with the course director (now my boss). It took me by surprise, but as the conversation continued, he offered me a job. It was tempting: the chance to build my own endobariatrics program with real institutional backing. The catch? It was in a city I had never been to, with no family or friends around. I politely said “no, thank you, I can’t.” He smiled, gave me his number, and said, “think about it.”

For the first time, I allowed myself to ask, “could I really leave my forever job?”

The Power of a Circle and a Spreadsheet

I leaned on my circle — a close group of fellowship friends who each took a turn being someone’s lifeline. We have monthly Zoom calls to talk about jobs, family, and career aspirations. When I shared my dilemma, I realized I wasn’t alone; one friend was also unhappy with her first job. Suddenly, we were asking one another, “can we really leave?”

I hired a career consultant familiar with physician visa issues — hands down, the best money I ever invested. The job search felt like dating: each interview was a first date; some needed a second or third date before I knew if it could be a match.

After every interview, I’d jump on Zoom with my circle. We’d screen-share my giant Excel spreadsheet — our decision matrix — with columns for everything I cared about:

- Institute

- Administrative Time

- Endobariatric support

- Director Title

- Salary

- On-call

- Vacation

- Proximity to airport

- Cost of living

- RVU percentage

- Endoscopy center buy-in

- Contract duration

- Support staff

- CME

We scored each job, line by line, and not a single job checked all the boxes. As I sat there in a state of decision paralysis, it became clear that this was not a simple decision.

The GI Community: A Small, Supportive World

The GI community is incredibly close-knit and kind-hearted. At every conference, I made a point to chat with as many colleagues as I could, to hear their perspectives on jobs and how they made tough career moves. Those conversations were real — no Google search or Excel sheet could offer the perspective and insight I gained by simply asking and leaning on the GI community.

Meanwhile, the person who had first offered me that job kept checking in, catching up at conferences, and bonding over our love for food and baking. With him, I never felt like I was being ‘interviewed’ — I felt valued. It did not feel like he was trying to fill a position with just anyone to improve the call pool. He genuinely wanted to understand what my goals were and how I envisioned my future. Through those conversations, he reminded me of my original passions, which were sidelined when so immersed in the daily routine.

I’ve learned that feeling valued doesn’t come from grand gestures in recruitment. It’s in the quiet signs of respect, trust, and being seen. He wasn’t looking for just anyone; he was looking for someone whose goals aligned with his group’s and someone in whom he wanted to invest. While others might chase the highest salary, the most flexible schedule, or the strongest ancillary support, I realized I valued something I did not realize that I was lacking until then: mentorship.

What I Learned: There is No Such Thing As “The Perfect Job”

After a full year of spreadsheets, Zoom calls, conference chats, and overthinking, I came to a big realization: there’s no perfect job — there’s no such thing as an ideal “forever job.” The only constant for humans is change. Our circumstances change, our priorities shift, our interests shuffle, and our finances evolve. The best job is simply the one that fits the stage of life you’re in at that given moment. For me, mentorship and growth became my top priorities, even if it meant moving away from family.

What Physicians Value Most in a Second Job

After their first job, early-career gastroenterologists often reevaluate what really matters. Recent surveys highlight four key priorities:

- Work-life balance:

In a 2022 CompHealth Group healthcare survey, 85% of physicians ranked work-life balance as their top job priority.3

- Mentorship and growth:

Nearly 1 in 3 physicians cited lack of mentorship or career advancement as their reason for leaving a first job, per the 2023 MGMA/Jackson Physician Search report.4

- Compensation:

While not always the main reason for leaving, 77% of physicians now list compensation as a top priority — a big jump from prior years.3

- Practice support:

Poor infrastructure, administrative overload, or understaffed teams are common dealbreakers. In the second job, physicians look for well-run practices with solid support staff and reduced burnout risk.5

Conclusion

Welcome the uncertainty, talk to your circle, lean on your community, and use a spreadsheet if you need to — but don’t forget to trust your gut. There’s no forever job or the perfect path, only the next move that feels most true to who you are in that moment.

Dr. Ismail (@mayyismail) is Assistant Professor of Clinical Medicine (Gastroenterology) at Temple University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She declares no conflicts of interest.

References

1. CHG Healthcare. Survey: 62% of physicians made a career change in the last two years. CHG Healthcare blog. June 10, 2024. Accessed August 5, 2025.

2. Berg S. Physicians in these 10 specialties are less likely to quit. AMA News. Published June 24, 2025. Accessed July 2025.

3. Saley C. Survey: Work/life balance is #1 priority in physicians’ job search. CHG Healthcare Insights. March 10, 2022. Accessed August 2025.

4. Medical Group Management Association; Jackson Physician Search. Early‑Career Physician Recruiting & Retention Playbook. October 23, 2023. Accessed August 2025.

5. Von Rosenvinge EC, et al. A crisis in scope: Recruitment and retention challenges reported by VA gastroenterology section chiefs. Fed Pract. 2024 Aug. doi:10.12788/fp.0504.

Introduction

For many of us in gastroenterology, landing that first attending job feels like the ultimate victory lap — the reward for all those years of training. We sign the contract, relocate, and imagine this will be our “forever job.” Reality often plays out differently.

In fact, 43% of physicians change jobs within five years, while 83% changed employers at least once in their careers.1 Even within our field — which is always in demand — turnover is high; 1 in 3 gastroenterologists are planning to leave their current role within two years.2 Why does this happen? More importantly, how do we navigate this transition with clarity and confidence as an early-career GI?

My Story: When I Dared to Change My “Forever Job”

When I signed my first attending contract, I didn’t negotiate a single thing. My priorities were simple: family in Toronto and visa requirements. After a decade of medical school, residency, and fellowship, everything else felt secondary. I was happy to be back home.

The job itself was good — reasonable hours, flexible colleagues, and ample opportunity to enhance my procedural skills. As I started carving out my niche in endobariatrics, the support I needed to grow further was not there. I kept telling myself that this job fulfilled my values and I needed to be patient: “this is my forever job. I am close to my family and that’s what matters.”

Then, during a suturing course at the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, I had a casual chat with the course director (now my boss). It took me by surprise, but as the conversation continued, he offered me a job. It was tempting: the chance to build my own endobariatrics program with real institutional backing. The catch? It was in a city I had never been to, with no family or friends around. I politely said “no, thank you, I can’t.” He smiled, gave me his number, and said, “think about it.”

For the first time, I allowed myself to ask, “could I really leave my forever job?”

The Power of a Circle and a Spreadsheet

I leaned on my circle — a close group of fellowship friends who each took a turn being someone’s lifeline. We have monthly Zoom calls to talk about jobs, family, and career aspirations. When I shared my dilemma, I realized I wasn’t alone; one friend was also unhappy with her first job. Suddenly, we were asking one another, “can we really leave?”

I hired a career consultant familiar with physician visa issues — hands down, the best money I ever invested. The job search felt like dating: each interview was a first date; some needed a second or third date before I knew if it could be a match.

After every interview, I’d jump on Zoom with my circle. We’d screen-share my giant Excel spreadsheet — our decision matrix — with columns for everything I cared about:

- Institute

- Administrative Time

- Endobariatric support

- Director Title

- Salary

- On-call

- Vacation

- Proximity to airport

- Cost of living

- RVU percentage

- Endoscopy center buy-in

- Contract duration

- Support staff

- CME

We scored each job, line by line, and not a single job checked all the boxes. As I sat there in a state of decision paralysis, it became clear that this was not a simple decision.

The GI Community: A Small, Supportive World

The GI community is incredibly close-knit and kind-hearted. At every conference, I made a point to chat with as many colleagues as I could, to hear their perspectives on jobs and how they made tough career moves. Those conversations were real — no Google search or Excel sheet could offer the perspective and insight I gained by simply asking and leaning on the GI community.

Meanwhile, the person who had first offered me that job kept checking in, catching up at conferences, and bonding over our love for food and baking. With him, I never felt like I was being ‘interviewed’ — I felt valued. It did not feel like he was trying to fill a position with just anyone to improve the call pool. He genuinely wanted to understand what my goals were and how I envisioned my future. Through those conversations, he reminded me of my original passions, which were sidelined when so immersed in the daily routine.

I’ve learned that feeling valued doesn’t come from grand gestures in recruitment. It’s in the quiet signs of respect, trust, and being seen. He wasn’t looking for just anyone; he was looking for someone whose goals aligned with his group’s and someone in whom he wanted to invest. While others might chase the highest salary, the most flexible schedule, or the strongest ancillary support, I realized I valued something I did not realize that I was lacking until then: mentorship.

What I Learned: There is No Such Thing As “The Perfect Job”

After a full year of spreadsheets, Zoom calls, conference chats, and overthinking, I came to a big realization: there’s no perfect job — there’s no such thing as an ideal “forever job.” The only constant for humans is change. Our circumstances change, our priorities shift, our interests shuffle, and our finances evolve. The best job is simply the one that fits the stage of life you’re in at that given moment. For me, mentorship and growth became my top priorities, even if it meant moving away from family.

What Physicians Value Most in a Second Job

After their first job, early-career gastroenterologists often reevaluate what really matters. Recent surveys highlight four key priorities:

- Work-life balance:

In a 2022 CompHealth Group healthcare survey, 85% of physicians ranked work-life balance as their top job priority.3

- Mentorship and growth:

Nearly 1 in 3 physicians cited lack of mentorship or career advancement as their reason for leaving a first job, per the 2023 MGMA/Jackson Physician Search report.4

- Compensation:

While not always the main reason for leaving, 77% of physicians now list compensation as a top priority — a big jump from prior years.3

- Practice support:

Poor infrastructure, administrative overload, or understaffed teams are common dealbreakers. In the second job, physicians look for well-run practices with solid support staff and reduced burnout risk.5

Conclusion

Welcome the uncertainty, talk to your circle, lean on your community, and use a spreadsheet if you need to — but don’t forget to trust your gut. There’s no forever job or the perfect path, only the next move that feels most true to who you are in that moment.

Dr. Ismail (@mayyismail) is Assistant Professor of Clinical Medicine (Gastroenterology) at Temple University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She declares no conflicts of interest.

References

1. CHG Healthcare. Survey: 62% of physicians made a career change in the last two years. CHG Healthcare blog. June 10, 2024. Accessed August 5, 2025.

2. Berg S. Physicians in these 10 specialties are less likely to quit. AMA News. Published June 24, 2025. Accessed July 2025.

3. Saley C. Survey: Work/life balance is #1 priority in physicians’ job search. CHG Healthcare Insights. March 10, 2022. Accessed August 2025.

4. Medical Group Management Association; Jackson Physician Search. Early‑Career Physician Recruiting & Retention Playbook. October 23, 2023. Accessed August 2025.

5. Von Rosenvinge EC, et al. A crisis in scope: Recruitment and retention challenges reported by VA gastroenterology section chiefs. Fed Pract. 2024 Aug. doi:10.12788/fp.0504.

Introduction

For many of us in gastroenterology, landing that first attending job feels like the ultimate victory lap — the reward for all those years of training. We sign the contract, relocate, and imagine this will be our “forever job.” Reality often plays out differently.

In fact, 43% of physicians change jobs within five years, while 83% changed employers at least once in their careers.1 Even within our field — which is always in demand — turnover is high; 1 in 3 gastroenterologists are planning to leave their current role within two years.2 Why does this happen? More importantly, how do we navigate this transition with clarity and confidence as an early-career GI?

My Story: When I Dared to Change My “Forever Job”

When I signed my first attending contract, I didn’t negotiate a single thing. My priorities were simple: family in Toronto and visa requirements. After a decade of medical school, residency, and fellowship, everything else felt secondary. I was happy to be back home.

The job itself was good — reasonable hours, flexible colleagues, and ample opportunity to enhance my procedural skills. As I started carving out my niche in endobariatrics, the support I needed to grow further was not there. I kept telling myself that this job fulfilled my values and I needed to be patient: “this is my forever job. I am close to my family and that’s what matters.”

Then, during a suturing course at the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, I had a casual chat with the course director (now my boss). It took me by surprise, but as the conversation continued, he offered me a job. It was tempting: the chance to build my own endobariatrics program with real institutional backing. The catch? It was in a city I had never been to, with no family or friends around. I politely said “no, thank you, I can’t.” He smiled, gave me his number, and said, “think about it.”

For the first time, I allowed myself to ask, “could I really leave my forever job?”

The Power of a Circle and a Spreadsheet

I leaned on my circle — a close group of fellowship friends who each took a turn being someone’s lifeline. We have monthly Zoom calls to talk about jobs, family, and career aspirations. When I shared my dilemma, I realized I wasn’t alone; one friend was also unhappy with her first job. Suddenly, we were asking one another, “can we really leave?”

I hired a career consultant familiar with physician visa issues — hands down, the best money I ever invested. The job search felt like dating: each interview was a first date; some needed a second or third date before I knew if it could be a match.

After every interview, I’d jump on Zoom with my circle. We’d screen-share my giant Excel spreadsheet — our decision matrix — with columns for everything I cared about:

- Institute

- Administrative Time

- Endobariatric support

- Director Title

- Salary

- On-call

- Vacation

- Proximity to airport

- Cost of living

- RVU percentage

- Endoscopy center buy-in

- Contract duration

- Support staff

- CME

We scored each job, line by line, and not a single job checked all the boxes. As I sat there in a state of decision paralysis, it became clear that this was not a simple decision.

The GI Community: A Small, Supportive World

The GI community is incredibly close-knit and kind-hearted. At every conference, I made a point to chat with as many colleagues as I could, to hear their perspectives on jobs and how they made tough career moves. Those conversations were real — no Google search or Excel sheet could offer the perspective and insight I gained by simply asking and leaning on the GI community.

Meanwhile, the person who had first offered me that job kept checking in, catching up at conferences, and bonding over our love for food and baking. With him, I never felt like I was being ‘interviewed’ — I felt valued. It did not feel like he was trying to fill a position with just anyone to improve the call pool. He genuinely wanted to understand what my goals were and how I envisioned my future. Through those conversations, he reminded me of my original passions, which were sidelined when so immersed in the daily routine.

I’ve learned that feeling valued doesn’t come from grand gestures in recruitment. It’s in the quiet signs of respect, trust, and being seen. He wasn’t looking for just anyone; he was looking for someone whose goals aligned with his group’s and someone in whom he wanted to invest. While others might chase the highest salary, the most flexible schedule, or the strongest ancillary support, I realized I valued something I did not realize that I was lacking until then: mentorship.

What I Learned: There is No Such Thing As “The Perfect Job”

After a full year of spreadsheets, Zoom calls, conference chats, and overthinking, I came to a big realization: there’s no perfect job — there’s no such thing as an ideal “forever job.” The only constant for humans is change. Our circumstances change, our priorities shift, our interests shuffle, and our finances evolve. The best job is simply the one that fits the stage of life you’re in at that given moment. For me, mentorship and growth became my top priorities, even if it meant moving away from family.

What Physicians Value Most in a Second Job

After their first job, early-career gastroenterologists often reevaluate what really matters. Recent surveys highlight four key priorities:

- Work-life balance:

In a 2022 CompHealth Group healthcare survey, 85% of physicians ranked work-life balance as their top job priority.3

- Mentorship and growth:

Nearly 1 in 3 physicians cited lack of mentorship or career advancement as their reason for leaving a first job, per the 2023 MGMA/Jackson Physician Search report.4

- Compensation:

While not always the main reason for leaving, 77% of physicians now list compensation as a top priority — a big jump from prior years.3

- Practice support:

Poor infrastructure, administrative overload, or understaffed teams are common dealbreakers. In the second job, physicians look for well-run practices with solid support staff and reduced burnout risk.5

Conclusion

Welcome the uncertainty, talk to your circle, lean on your community, and use a spreadsheet if you need to — but don’t forget to trust your gut. There’s no forever job or the perfect path, only the next move that feels most true to who you are in that moment.

Dr. Ismail (@mayyismail) is Assistant Professor of Clinical Medicine (Gastroenterology) at Temple University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She declares no conflicts of interest.

References

1. CHG Healthcare. Survey: 62% of physicians made a career change in the last two years. CHG Healthcare blog. June 10, 2024. Accessed August 5, 2025.

2. Berg S. Physicians in these 10 specialties are less likely to quit. AMA News. Published June 24, 2025. Accessed July 2025.

3. Saley C. Survey: Work/life balance is #1 priority in physicians’ job search. CHG Healthcare Insights. March 10, 2022. Accessed August 2025.

4. Medical Group Management Association; Jackson Physician Search. Early‑Career Physician Recruiting & Retention Playbook. October 23, 2023. Accessed August 2025.

5. Von Rosenvinge EC, et al. A crisis in scope: Recruitment and retention challenges reported by VA gastroenterology section chiefs. Fed Pract. 2024 Aug. doi:10.12788/fp.0504.

Developing the Next Generation of GI Leaders

In this episode of Private Practice Perspectives, Dr. Naresh Gunaratnam, current president and board chair of Digestive Health Physician Association, speaks with Dr. Larry Kim, current president of AGA, about .

In this episode of Private Practice Perspectives, Dr. Naresh Gunaratnam, current president and board chair of Digestive Health Physician Association, speaks with Dr. Larry Kim, current president of AGA, about .

In this episode of Private Practice Perspectives, Dr. Naresh Gunaratnam, current president and board chair of Digestive Health Physician Association, speaks with Dr. Larry Kim, current president of AGA, about .

Approach to Weight Management in GI Practice

Introduction

The majority of patients in the United States are now overweight or obese, and as gastroenterologists we treat a number of conditions that are caused or worsened by obesity.1 Cirrhosis related to metabolic associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) is now a leading indication for liver transplantation in the US2 and obesity is a clear risk factor for all major malignancies of the GI tract, including esophageal, gastric cardia, pancreatic, liver, gallbladder, colon, and rectum.3 Obesity is associated with dysbiosis and impacts barrier function: increasing permeability, abnormal gut bacterial translocation, and inflammation.4 It is more common than malnutrition in our patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), where it impacts response to biologic drugs, increases the technical difficulty of surgeries, such as IPAA, and is associated with worse surgical outcomes.5 Furthermore, patients with obesity may be less likely to undergo preventative cancer screenings and are at increased risk related to sedation for endoscopic procedures.6 With over 40% of Americans suffering from obesity, and increasingly effective treatments available,

Understanding the Mechanisms of Obesity

There are complex orexigenic and anorexigenic brain pathways in the hypothalamus which control global energy balance.7 Obesity results when energy intake exceeds energy expenditure. While overeating and a sedentary lifestyle are commonly blamed, there are a number of elements that contribute, including genetics, medical conditions, medications, psychosocial factors, and environmental components. For example, sleep loss contributes to weight gain by several mechanisms including increasing ghrelin and decreasing leptin levels, thereby increasing hunger and appetite, as well as by decreasing insulin sensitivity and increasing cortisol. Subjects exposed to sleep deprivation in research settings take in 550 kcal more the following day.8 Medications used commonly in GI practice including corticosteroids, antihistamines, propranolol, and amitriptyline, are obesogenic9 and cannabis can impact hypothalamic pathways to stimulate hunger.10

When patients diet or exercise to lose weight, as we have traditionally advised, there are strong hormonal changes and metabolic adaptations that occur to preserve the defended fat mass or “set point.” Loss of adipose tissue results in decreased production of leptin, a hormone that stimulates satiety pathways and inhibits orexigenic pathways, greatly increasing hunger and cravings. Increases in ghrelin production by the stomach decreases perceptions of fullness. With weight loss, energy requirements decrease, and muscles become more efficient, meaning fewer kcal are needed to maintain bodily processes.11 Eventually a plateau is reached, while motivation to diet and restraint around food wane, and hedonistic (reward) pathways are activated. These powerful factors result in the regain of lost weight within one year in the majority of patients.

Implementing Weight Management into GI Practice

Given the stigma and bias around obesity, patients often feel shame and vulnerability around the condition. It is important to have empathy in your approach, asking permission to discuss weight and using patient-first language (e.g. “patient with obesity” not “obese patient”). While BMI is predictive of health outcomes, it does not measure body fat percentage and may be misleading, such as in muscular individuals. Other measures of adiposity including waist circumference and body composition testing, such as with DEXA, may provide additional data. A BMI of 30 or above defines obesity, though newer definitions incorporate related symptoms, organ disfunction, and metabolic abnormalities into the term “clinical obesity.”12 Asian patients experience metabolic complications at a lower BMI, and therefore the definition of obese is 27.5kg/m2 in this population.

Begin by taking a weight history. Has this been a lifelong struggle or is there a particular life circumstance, such as working a third shift or recent pregnancy which precipitated weight gain? Patients should be asked about binge eating or eating late into the evening or waking at night to eat, as these disordered eating behaviors are managed with specific medications and behavioral therapies. Inquire about sleep duration and quality and refer for a sleep study if there is suspicion for obstructive sleep apnea. Other weight-related comorbidities including hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and MAFLD should be considered and merit a more aggressive approach, as does more severe obesity (class III, BMI ≥40). Questions about marijuana and alcohol use as well as review of the medication list for obesogenic medications can provide further insight into modifiable contributing factors.

Pillars of Weight Management

The internet is awash with trendy diet recommendations, and widespread misconceptions about obesity management are even ingrained into how physicians approach the disease. It is critical to remember that this is not a consequence of bad choices or lack of self-control. Exercise alone is insufficient to result in significant weight loss.13 Furthermore, whether it is through low fat, low carb, or intermittent fasting, weight loss will occur with calorie deficit.14 Evidence-based diet and lifestyle recommendations to lay the groundwork for success should be discussed at each visit (see Table 1). The Mediterranean diet is recommended for weight loss as well as for several GI disorders (i.e., MAFLD and IBD) and is the optimal eating strategy for cardiovascular health.15 Patients should be advised to engage in 150 minutes of moderate exercise per week, such as brisk walking, and should incorporate resistance training to build muscle and maintain bone density.

Anti-obesity Medications

There are a number of medications, either FDA approved or used off label, for treatment of obesity (see Table 2).16 All are indicated for patients with a BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2 or for those with a BMI between 27-29 kg/m2 with weight-related comorbidities and should be used in combination with diet and lifestyle interventions. None are approved or safe in pregnancy. Mechanisms of action vary by type and include decreased appetite, increased energy expenditure, improved insulin sensitivity, and interfere with absorption.

The newest and most effective anti-obesity medications (AOM), the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RA) are derived from gut hormones secreted in the distal small bowel and colon in response to a meal, which function to delay gastric emptying, increase insulin release from the pancreas, and reduce hepatic gluconeogenesis. Central nervous system effects are not yet entirely understood, but function to decrease appetite and increase satiety. Initially developed for treatment of T2DM, observed weight reduction in patients treated with GLP-1 RA led to clinical trials for treatment of obesity. Semaglutide treatment resulted in weight reduction of 16.9% of total body weight (TBW), and one third of subjects lost ≥ 20% of TBW.17 Tirzepatide combines GLP-1 RA and a gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) receptor agonist, which also has an incretin effect and functions to slow gastric emptying. In the pivotal SURMOUNT trial, approximately 58% of patients achieved ≥20% loss of TBW18 with 15mg weekly dosing of tirzepatide. This class of drugs is a logical choice in patients with T2DM and obesity. Long-term treatment appears necessary, as patients typically regain two-thirds of lost weight within a year after GLP-1 RA are stopped.

Based on tumors observed in rodents, GLP-1 RA are contraindicated in patients with a personal or family history of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN II) or medullary thyroid cancer. These tumors have not been observed in humans treated with GLP-1 RA. They should be used with caution in patients with history of pancreatitis, gastroparesis, or diabetic retinopathy, though a recent systematic review and meta-analysis suggests showed little to no increased risk for biliary events from GLP-1 RA.19 Side effects are most commonly gastrointestinal in nature (nausea, reflux, constipation or diarrhea) and are typically most severe with initiation of the drug and with dose escalation. Side effects can be mitigated by initiating these drugs at lowest doses and gradually titrating up (every four weeks) based on effectiveness and tolerability. Antisecretory, antiemetic, and laxative medications can also be used to help manage GLP-1 RA related side effects.

There is no reason to escalate to highest doses if patients are experiencing weight loss and reduction in food cravings at lower doses. Both semaglutide and tirzepatide are administered subcutaneously every seven days. Once patients have reached goal weight, they can either continue maintenance therapy at that same dose/interval, or if motivated to do so, may gradually reduce the weekly dose in a stepwise approach to determine the minimally effective dose to maintain weight loss. There are not yet published maintenance studies to guide this process. Currently the price of GLP-1 RA and inconsistent insurance coverage make them inaccessible to many patients. The manufacturers of both semaglutide and tirzepatide offer direct to consumer pricing and home delivery.

Bariatric Surgery

In patients with higher BMI (≥35kg/m2) or those with BMI ≥30kg/m2 and obesity-related metabolic disease and the desire to avoid lifelong medications or who fail or are intolerant of AOM, bariatric options should be considered.20 Sleeve gastrectomy has become the most performed surgery for treatment of obesity. It is a restrictive procedure, removing 80% of the stomach, but a drop in circulating levels of ghrelin afterwards also leads to decreased feelings of hunger. It results in weight loss of 25-30% TBW loss. It is not a good choice for patients who suffer from severe GERD, as this typically worsens afterwards; furthermore, de novo Barrett’s has been observed in nearly 6% of patients who undergo sleeve gastrectomy.21

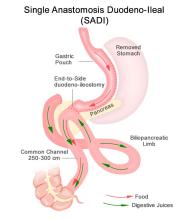

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass is a restrictive and malabsorptive procedure, resulting in 30-35% TBW loss. It has beneficial and immediate metabolic effects, including increased release of endogenous GLP-1, which leads to improvements in weight-related T2DM. The newer single anastomosis duodenal-ileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy (SADI-S) starts with a sleeve gastrectomy, making a smaller tube-shaped stomach. The duodenum is divided just after the stomach and then a loop of ileum is brought up and connected to the stomach (see Figure 1). This procedure is highly effective, with patients losing 75-95% of excess body weight and is becoming a preferred option for patients with greater BMI (≥50kg/m2). It is also an option for patients who have already had a sleeve gastrectomy and are seeking further weight loss. Because there is only one anastomosis, perioperative complications, such as anastomotic leaks, are reduced. The risk of micronutrient deficiencies is present with all malabsorptive procedures, and these patients must supplement with multivitamins, iron, vitamin D, and calcium.

Endoscopic Therapies

Endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies (EBMTs) have been increasingly studied and utilized, and this less invasive option may be more appropriate for or attractive to many patients. Intragastric balloons, which reduce meal volume and delay gastric emptying, can be used short term only (six months) resulting in loss of about 6.9% of total body weight (TBW) greater than lifestyle modification (LM) alone, and may be considered in limited situations, such as need for pre-operative weight loss to reduce risks in very obese individuals.22

Endoscopic gastric remodeling (EGR), also known as endoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (ESG), is a purely restrictive procedure in which the stomach is cinched to resize and reshape using an endoscopic suturing device (see Figure 2).23 It is an option for patients with class 1 or 2 obesity, with data from a randomized controlled trial in this population demonstrating mean percentage of TBW loss of 13.6% at 52 weeks compared to 0.8% in those treated with LM alone.24 A recent meta-analysis of 21 observational studies, including patients with higher BMIs (32.5 to 49.9 kg/m2) showed pooled average weight loss of 17.3% TBW at 12 months with EGR.22 This procedure has potential advantages of fewer complications, quicker recovery, and much less new-onset GERD compared to laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Furthermore, it may be utilized in combination with AOMs to achieve optimum weight loss and metabolic outcomes.25,26 Potential adverse events include abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting (which may be severe), as well as rare instances of intra/extra luminal bleeding or abdominal abscess requiring drainage.22

Recent joint American/European Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guidelines suggest the use of EBMTs plus lifestyle modification in patients with a BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2, or with a BMI of 27.0-29.9 kg/m2 with at least 1 obesity-related comorbidity.22 Small bowel interventions including duodenal-jejunal bypass liner and duodenal mucosal resurfacing are being investigated for patients with obesity and type 2 diabetes but not yet commercially available.

Conclusion

Given the overlap of obesity with many GI disorders, it is entirely appropriate for gastroenterologists to consider it worthy of aggressive treatment, particularly in patients with MAFLD and other serious weight related comorbidities. With a compassionate and empathetic approach, and a number of highly effective medical, endoscopic, and surgical therapies now available, weight management has the potential to be extremely rewarding when implemented in GI practice.

Dr. Kelly is based in the Department of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, Massachusetts. She serves on the clinical advisory board for OpenBiome (unpaid) and has served on an advisory board for Eli Lilly and Company.

References

1. Hales CM, et al. Prevalence of Obesity and Severe Obesity Among Adults: United States, 2017-2018. NCHS Data Brief 2020 Feb:(360):1–8.

2. Pais R, et al. NAFLD and liver transplantation: Current burden and expected challenges. J Hepatol. 2016 Dec. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.07.033.

3. Lauby-Secretan B, et al. Body Fatness and Cancer--Viewpoint of the IARC Working Group. N Engl J Med. 2016 Aug. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1606602.

4. Kim A. Dysbiosis: A Review Highlighting Obesity and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015 Nov-Dec. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000356.

5. Singh S, et al. Obesity in IBD: epidemiology, pathogenesis, disease course and treatment outcomes. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Feb. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.181.

6. Sundararaman L, Goudra B. Sedation for GI Endoscopy in the Morbidly Obese: Challenges and Possible Solutions. J Clin Med. 2024 Aug. doi: 10.3390/jcm13164635.

7. Bombassaro B, et al. The hypothalamus as the central regulator of energy balance and its impact on current and future obesity treatments. Arch Endocrinol Metab. 2024 Nov. doi: 10.20945/2359-4292-2024-0082.

8. Beccuti G, Pannain S. Sleep and obesity. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2011 Jul. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3283479109.

9. Desalermos A, et al. Effect of Obesogenic Medications on Weight-Loss Outcomes in a Behavioral Weight-Management Program. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2019 May. doi: 10.1002/oby.22444.

10. Lord MN, Noble EE. Hypothalamic cannabinoid signaling: Consequences for eating behavior. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2024 Oct. doi: 10.1002/prp2.1251.

11. Farhana A, Rehman A. Metabolic Consequences of Weight Reduction. [Updated 2023 Jul 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK572145/.

12. Rubino F, et al. Definition and diagnostic criteria of clinical obesity. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025 Mar. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(24)00316-4.

13. Cox CE. Role of Physical Activity for Weight Loss and Weight Maintenance. Diabetes Spectr. 2017 Aug. doi: 10.2337/ds17-0013.

14. Chaput JP, et al. Widespread misconceptions about obesity. Can Fam Physician. 2014 Nov. PMID: 25392431.

15. Muscogiuri G, et al. Mediterranean Diet and Obesity-related Disorders: What is the Evidence? Curr Obes Rep. 2022 Dec. doi: 10.1007/s13679-022-00481-1.

16. Gudzune KA, Kushner RF. Medications for Obesity: A Review. JAMA. 2024 Aug. doi: 10.1001/jama.2024.10816.

17. Wilding JPH, et al. Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults with Overweight or Obesity. N Engl J Med. 2021 Feb. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2032183.

18. Jastreboff AM, et al. Tirzepatide Once Weekly for the Treatment of Obesity. N Engl J Med. 2022 Jun. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2206038.

19. Chiang CH, et al. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists and Gastrointestinal Adverse Events: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. 2025 Nov. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2025.06.003.

20. Aderinto N, et al. Recent advances in bariatric surgery: a narrative review of weight loss procedures. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2023 Nov. doi: 10.1097/MS9.0000000000001472.

21. Chandan S, et al. Risk of De Novo Barrett’s Esophagus Post Sleeve Gastrectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Studies With Long-Term Follow-Up. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2024.06.041.

22. Jirapinyo P, et al. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy-European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guideline on primary endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies for adults with obesity. Gastrointest Endosc. 2024 Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2023.12.004.

23. Nduma BN, et al. Endoscopic Gastric Sleeve: A Review of Literature. Cureus. 2023 Mar. doi: 10.7759/cureus.36353.

24. Abu Dayyeh BK, et al. Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty for treatment of class 1 and 2 obesity (MERIT): a prospective, multicentre, randomised trial. Lancet. 2022 Aug. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01280-6.

25. Gala K, et al. Outcomes of concomitant antiobesity medication use with endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty in clinical US settings. Obes Pillars. 2024 May. doi: 10.1016/j.obpill.2024.100112.

26. Chung CS, et al. Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty combined with anti-obesity medication for better control of weight and diabetes. Clin Endosc. 2025 May. doi: 10.5946/ce.2024.274.

Introduction

The majority of patients in the United States are now overweight or obese, and as gastroenterologists we treat a number of conditions that are caused or worsened by obesity.1 Cirrhosis related to metabolic associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) is now a leading indication for liver transplantation in the US2 and obesity is a clear risk factor for all major malignancies of the GI tract, including esophageal, gastric cardia, pancreatic, liver, gallbladder, colon, and rectum.3 Obesity is associated with dysbiosis and impacts barrier function: increasing permeability, abnormal gut bacterial translocation, and inflammation.4 It is more common than malnutrition in our patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), where it impacts response to biologic drugs, increases the technical difficulty of surgeries, such as IPAA, and is associated with worse surgical outcomes.5 Furthermore, patients with obesity may be less likely to undergo preventative cancer screenings and are at increased risk related to sedation for endoscopic procedures.6 With over 40% of Americans suffering from obesity, and increasingly effective treatments available,

Understanding the Mechanisms of Obesity

There are complex orexigenic and anorexigenic brain pathways in the hypothalamus which control global energy balance.7 Obesity results when energy intake exceeds energy expenditure. While overeating and a sedentary lifestyle are commonly blamed, there are a number of elements that contribute, including genetics, medical conditions, medications, psychosocial factors, and environmental components. For example, sleep loss contributes to weight gain by several mechanisms including increasing ghrelin and decreasing leptin levels, thereby increasing hunger and appetite, as well as by decreasing insulin sensitivity and increasing cortisol. Subjects exposed to sleep deprivation in research settings take in 550 kcal more the following day.8 Medications used commonly in GI practice including corticosteroids, antihistamines, propranolol, and amitriptyline, are obesogenic9 and cannabis can impact hypothalamic pathways to stimulate hunger.10

When patients diet or exercise to lose weight, as we have traditionally advised, there are strong hormonal changes and metabolic adaptations that occur to preserve the defended fat mass or “set point.” Loss of adipose tissue results in decreased production of leptin, a hormone that stimulates satiety pathways and inhibits orexigenic pathways, greatly increasing hunger and cravings. Increases in ghrelin production by the stomach decreases perceptions of fullness. With weight loss, energy requirements decrease, and muscles become more efficient, meaning fewer kcal are needed to maintain bodily processes.11 Eventually a plateau is reached, while motivation to diet and restraint around food wane, and hedonistic (reward) pathways are activated. These powerful factors result in the regain of lost weight within one year in the majority of patients.

Implementing Weight Management into GI Practice

Given the stigma and bias around obesity, patients often feel shame and vulnerability around the condition. It is important to have empathy in your approach, asking permission to discuss weight and using patient-first language (e.g. “patient with obesity” not “obese patient”). While BMI is predictive of health outcomes, it does not measure body fat percentage and may be misleading, such as in muscular individuals. Other measures of adiposity including waist circumference and body composition testing, such as with DEXA, may provide additional data. A BMI of 30 or above defines obesity, though newer definitions incorporate related symptoms, organ disfunction, and metabolic abnormalities into the term “clinical obesity.”12 Asian patients experience metabolic complications at a lower BMI, and therefore the definition of obese is 27.5kg/m2 in this population.

Begin by taking a weight history. Has this been a lifelong struggle or is there a particular life circumstance, such as working a third shift or recent pregnancy which precipitated weight gain? Patients should be asked about binge eating or eating late into the evening or waking at night to eat, as these disordered eating behaviors are managed with specific medications and behavioral therapies. Inquire about sleep duration and quality and refer for a sleep study if there is suspicion for obstructive sleep apnea. Other weight-related comorbidities including hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and MAFLD should be considered and merit a more aggressive approach, as does more severe obesity (class III, BMI ≥40). Questions about marijuana and alcohol use as well as review of the medication list for obesogenic medications can provide further insight into modifiable contributing factors.

Pillars of Weight Management

The internet is awash with trendy diet recommendations, and widespread misconceptions about obesity management are even ingrained into how physicians approach the disease. It is critical to remember that this is not a consequence of bad choices or lack of self-control. Exercise alone is insufficient to result in significant weight loss.13 Furthermore, whether it is through low fat, low carb, or intermittent fasting, weight loss will occur with calorie deficit.14 Evidence-based diet and lifestyle recommendations to lay the groundwork for success should be discussed at each visit (see Table 1). The Mediterranean diet is recommended for weight loss as well as for several GI disorders (i.e., MAFLD and IBD) and is the optimal eating strategy for cardiovascular health.15 Patients should be advised to engage in 150 minutes of moderate exercise per week, such as brisk walking, and should incorporate resistance training to build muscle and maintain bone density.

Anti-obesity Medications

There are a number of medications, either FDA approved or used off label, for treatment of obesity (see Table 2).16 All are indicated for patients with a BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2 or for those with a BMI between 27-29 kg/m2 with weight-related comorbidities and should be used in combination with diet and lifestyle interventions. None are approved or safe in pregnancy. Mechanisms of action vary by type and include decreased appetite, increased energy expenditure, improved insulin sensitivity, and interfere with absorption.

The newest and most effective anti-obesity medications (AOM), the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RA) are derived from gut hormones secreted in the distal small bowel and colon in response to a meal, which function to delay gastric emptying, increase insulin release from the pancreas, and reduce hepatic gluconeogenesis. Central nervous system effects are not yet entirely understood, but function to decrease appetite and increase satiety. Initially developed for treatment of T2DM, observed weight reduction in patients treated with GLP-1 RA led to clinical trials for treatment of obesity. Semaglutide treatment resulted in weight reduction of 16.9% of total body weight (TBW), and one third of subjects lost ≥ 20% of TBW.17 Tirzepatide combines GLP-1 RA and a gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) receptor agonist, which also has an incretin effect and functions to slow gastric emptying. In the pivotal SURMOUNT trial, approximately 58% of patients achieved ≥20% loss of TBW18 with 15mg weekly dosing of tirzepatide. This class of drugs is a logical choice in patients with T2DM and obesity. Long-term treatment appears necessary, as patients typically regain two-thirds of lost weight within a year after GLP-1 RA are stopped.

Based on tumors observed in rodents, GLP-1 RA are contraindicated in patients with a personal or family history of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN II) or medullary thyroid cancer. These tumors have not been observed in humans treated with GLP-1 RA. They should be used with caution in patients with history of pancreatitis, gastroparesis, or diabetic retinopathy, though a recent systematic review and meta-analysis suggests showed little to no increased risk for biliary events from GLP-1 RA.19 Side effects are most commonly gastrointestinal in nature (nausea, reflux, constipation or diarrhea) and are typically most severe with initiation of the drug and with dose escalation. Side effects can be mitigated by initiating these drugs at lowest doses and gradually titrating up (every four weeks) based on effectiveness and tolerability. Antisecretory, antiemetic, and laxative medications can also be used to help manage GLP-1 RA related side effects.

There is no reason to escalate to highest doses if patients are experiencing weight loss and reduction in food cravings at lower doses. Both semaglutide and tirzepatide are administered subcutaneously every seven days. Once patients have reached goal weight, they can either continue maintenance therapy at that same dose/interval, or if motivated to do so, may gradually reduce the weekly dose in a stepwise approach to determine the minimally effective dose to maintain weight loss. There are not yet published maintenance studies to guide this process. Currently the price of GLP-1 RA and inconsistent insurance coverage make them inaccessible to many patients. The manufacturers of both semaglutide and tirzepatide offer direct to consumer pricing and home delivery.

Bariatric Surgery

In patients with higher BMI (≥35kg/m2) or those with BMI ≥30kg/m2 and obesity-related metabolic disease and the desire to avoid lifelong medications or who fail or are intolerant of AOM, bariatric options should be considered.20 Sleeve gastrectomy has become the most performed surgery for treatment of obesity. It is a restrictive procedure, removing 80% of the stomach, but a drop in circulating levels of ghrelin afterwards also leads to decreased feelings of hunger. It results in weight loss of 25-30% TBW loss. It is not a good choice for patients who suffer from severe GERD, as this typically worsens afterwards; furthermore, de novo Barrett’s has been observed in nearly 6% of patients who undergo sleeve gastrectomy.21

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass is a restrictive and malabsorptive procedure, resulting in 30-35% TBW loss. It has beneficial and immediate metabolic effects, including increased release of endogenous GLP-1, which leads to improvements in weight-related T2DM. The newer single anastomosis duodenal-ileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy (SADI-S) starts with a sleeve gastrectomy, making a smaller tube-shaped stomach. The duodenum is divided just after the stomach and then a loop of ileum is brought up and connected to the stomach (see Figure 1). This procedure is highly effective, with patients losing 75-95% of excess body weight and is becoming a preferred option for patients with greater BMI (≥50kg/m2). It is also an option for patients who have already had a sleeve gastrectomy and are seeking further weight loss. Because there is only one anastomosis, perioperative complications, such as anastomotic leaks, are reduced. The risk of micronutrient deficiencies is present with all malabsorptive procedures, and these patients must supplement with multivitamins, iron, vitamin D, and calcium.

Endoscopic Therapies

Endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies (EBMTs) have been increasingly studied and utilized, and this less invasive option may be more appropriate for or attractive to many patients. Intragastric balloons, which reduce meal volume and delay gastric emptying, can be used short term only (six months) resulting in loss of about 6.9% of total body weight (TBW) greater than lifestyle modification (LM) alone, and may be considered in limited situations, such as need for pre-operative weight loss to reduce risks in very obese individuals.22

Endoscopic gastric remodeling (EGR), also known as endoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (ESG), is a purely restrictive procedure in which the stomach is cinched to resize and reshape using an endoscopic suturing device (see Figure 2).23 It is an option for patients with class 1 or 2 obesity, with data from a randomized controlled trial in this population demonstrating mean percentage of TBW loss of 13.6% at 52 weeks compared to 0.8% in those treated with LM alone.24 A recent meta-analysis of 21 observational studies, including patients with higher BMIs (32.5 to 49.9 kg/m2) showed pooled average weight loss of 17.3% TBW at 12 months with EGR.22 This procedure has potential advantages of fewer complications, quicker recovery, and much less new-onset GERD compared to laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Furthermore, it may be utilized in combination with AOMs to achieve optimum weight loss and metabolic outcomes.25,26 Potential adverse events include abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting (which may be severe), as well as rare instances of intra/extra luminal bleeding or abdominal abscess requiring drainage.22

Recent joint American/European Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guidelines suggest the use of EBMTs plus lifestyle modification in patients with a BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2, or with a BMI of 27.0-29.9 kg/m2 with at least 1 obesity-related comorbidity.22 Small bowel interventions including duodenal-jejunal bypass liner and duodenal mucosal resurfacing are being investigated for patients with obesity and type 2 diabetes but not yet commercially available.

Conclusion

Given the overlap of obesity with many GI disorders, it is entirely appropriate for gastroenterologists to consider it worthy of aggressive treatment, particularly in patients with MAFLD and other serious weight related comorbidities. With a compassionate and empathetic approach, and a number of highly effective medical, endoscopic, and surgical therapies now available, weight management has the potential to be extremely rewarding when implemented in GI practice.

Dr. Kelly is based in the Department of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, Massachusetts. She serves on the clinical advisory board for OpenBiome (unpaid) and has served on an advisory board for Eli Lilly and Company.

References

1. Hales CM, et al. Prevalence of Obesity and Severe Obesity Among Adults: United States, 2017-2018. NCHS Data Brief 2020 Feb:(360):1–8.

2. Pais R, et al. NAFLD and liver transplantation: Current burden and expected challenges. J Hepatol. 2016 Dec. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.07.033.

3. Lauby-Secretan B, et al. Body Fatness and Cancer--Viewpoint of the IARC Working Group. N Engl J Med. 2016 Aug. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1606602.

4. Kim A. Dysbiosis: A Review Highlighting Obesity and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015 Nov-Dec. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000356.

5. Singh S, et al. Obesity in IBD: epidemiology, pathogenesis, disease course and treatment outcomes. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Feb. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.181.

6. Sundararaman L, Goudra B. Sedation for GI Endoscopy in the Morbidly Obese: Challenges and Possible Solutions. J Clin Med. 2024 Aug. doi: 10.3390/jcm13164635.

7. Bombassaro B, et al. The hypothalamus as the central regulator of energy balance and its impact on current and future obesity treatments. Arch Endocrinol Metab. 2024 Nov. doi: 10.20945/2359-4292-2024-0082.

8. Beccuti G, Pannain S. Sleep and obesity. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2011 Jul. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3283479109.

9. Desalermos A, et al. Effect of Obesogenic Medications on Weight-Loss Outcomes in a Behavioral Weight-Management Program. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2019 May. doi: 10.1002/oby.22444.

10. Lord MN, Noble EE. Hypothalamic cannabinoid signaling: Consequences for eating behavior. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2024 Oct. doi: 10.1002/prp2.1251.

11. Farhana A, Rehman A. Metabolic Consequences of Weight Reduction. [Updated 2023 Jul 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK572145/.

12. Rubino F, et al. Definition and diagnostic criteria of clinical obesity. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025 Mar. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(24)00316-4.

13. Cox CE. Role of Physical Activity for Weight Loss and Weight Maintenance. Diabetes Spectr. 2017 Aug. doi: 10.2337/ds17-0013.

14. Chaput JP, et al. Widespread misconceptions about obesity. Can Fam Physician. 2014 Nov. PMID: 25392431.

15. Muscogiuri G, et al. Mediterranean Diet and Obesity-related Disorders: What is the Evidence? Curr Obes Rep. 2022 Dec. doi: 10.1007/s13679-022-00481-1.

16. Gudzune KA, Kushner RF. Medications for Obesity: A Review. JAMA. 2024 Aug. doi: 10.1001/jama.2024.10816.

17. Wilding JPH, et al. Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults with Overweight or Obesity. N Engl J Med. 2021 Feb. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2032183.

18. Jastreboff AM, et al. Tirzepatide Once Weekly for the Treatment of Obesity. N Engl J Med. 2022 Jun. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2206038.

19. Chiang CH, et al. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists and Gastrointestinal Adverse Events: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. 2025 Nov. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2025.06.003.

20. Aderinto N, et al. Recent advances in bariatric surgery: a narrative review of weight loss procedures. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2023 Nov. doi: 10.1097/MS9.0000000000001472.

21. Chandan S, et al. Risk of De Novo Barrett’s Esophagus Post Sleeve Gastrectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Studies With Long-Term Follow-Up. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2024.06.041.

22. Jirapinyo P, et al. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy-European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guideline on primary endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies for adults with obesity. Gastrointest Endosc. 2024 Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2023.12.004.

23. Nduma BN, et al. Endoscopic Gastric Sleeve: A Review of Literature. Cureus. 2023 Mar. doi: 10.7759/cureus.36353.

24. Abu Dayyeh BK, et al. Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty for treatment of class 1 and 2 obesity (MERIT): a prospective, multicentre, randomised trial. Lancet. 2022 Aug. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01280-6.

25. Gala K, et al. Outcomes of concomitant antiobesity medication use with endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty in clinical US settings. Obes Pillars. 2024 May. doi: 10.1016/j.obpill.2024.100112.

26. Chung CS, et al. Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty combined with anti-obesity medication for better control of weight and diabetes. Clin Endosc. 2025 May. doi: 10.5946/ce.2024.274.

Introduction