User login

Hospital medicine gains popularity among newly minted physicians

In a new study, published in Annals of Internal Medicine, researchers from ABIM reviewed certification data from 67,902 general internists, accounting for 80% of all general internists certified in the United States from 1990 to 2017.

The researchers also used data from Medicare fee-for-service claims from 2008-2018 to measure and categorize practice setting types. The claims were from patients aged 65 years or older with at least 20 evaluation and management visits each year. Practice settings were categorized as hospitalist, outpatient, or mixed.

“ABIM is always working to understand the real-life experience of physicians, and this project grew out of that sort of analysis,” lead author Bradley M. Gray, PhD, a health services researcher at ABIM in Philadelphia, said in an interview. “We wanted to better understand practice setting, because that relates to the kinds of questions that we ask on our certifying exams. When we did this, we noticed a trend toward hospital medicine.”

Overall, the percentages of general internists in hospitalist practice and outpatient-only practice increased during the study period, from 25% to 40% and from 23% to 38%, respectively. By contrast, the percentage of general internists in a mixed-practice setting decreased from 52% to 23%, a 56% decline. Most of the physicians who left the mixed practice setting switched to outpatient-only practices.

Among the internists certified in 2017, 71% practiced as hospitalists, compared with 8% practicing as outpatient-only physicians. Most physicians remained in their original choice of practice setting. For physicians certified in 1999 and 2012, 86% and 85%, respectively, of those who chose hospitalist medicine remained in the hospital setting 5 years later, as did 95% of outpatient physicians, but only 57% of mixed-practice physicians.

The shift to outpatient practice among senior physicians offset the potential decline in outpatient primary care resulting from the increased choice of hospitalist medicine by new internists, the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the reliance on Medicare fee-for-service claims, the researchers noted.

“We were surprised by both the dramatic shift toward hospital medicine by new physicians and the shift to outpatient only (an extreme category) for more senior physicians,” Dr. Gray said in an interview.

The shift toward outpatient practice among older physicians may be driven by convenience, said Dr. Gray. “I suspect that it is more efficient to specialize in terms of practice setting. Only seeing patients in the outpatient setting means that you don’t have to travel to the hospital, which can be time consuming.

“Also, with fewer new physicians going into primary care, older physicians need to focus on outpatient visits. This could be problematic in the future as more senior physicians retire and are replaced by new physicians who focus on hospital care,” which could lead to more shortages in primary care physicians, he explained.

The trend toward hospital medicine as a career has been going on since before the pandemic, said Dr. Gray. “I don’t think the pandemic will ultimately impact this trend. That said, at least in the short run, there may have been a decreased demand for primary care, but that is just my speculation. As more data flow in we will be able to answer this question more directly.”

Next steps for research included digging deeper into the data to understand the nature of conditions facing hospitalists, Dr. Gray said.

Implications for primary care

“This study provides an updated snapshot of the popularity of hospital medicine,” said Bradley A. Sharpe, MD, of the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. “It is also important to conduct this study now as health systems think about the challenge of providing high-quality primary care with a rapidly decreasing number of internists choosing to practice outpatient medicine.” Dr. Sharpe was not involved in the study.

“The most surprising finding to me was not the increase in general internists focusing on hospital medicine, but the amount of the increase; it is remarkable that nearly three quarters of general internists are choosing to practice as hospitalists,” Dr. Sharpe noted.

“I think there are a number of key factors at play,” he said. “First, as hospital medicine as a field is now more than 25 years old, hospitals and health systems have evolved to create hospital medicine jobs that are interesting, engaging, rewarding (financially and otherwise), doable, and sustainable. Second, being an outpatient internist is incredibly challenging; multiple studies have shown that it is essentially impossible to complete the evidence-based preventive care for a panel of patients on top of everything else. We know burnout rates are often higher among primary care and family medicine providers. On top of that, the expansion of electronic health records and patient access has led to a massive increase in messages to providers; this has been shown to be associated with burnout.”

The potential impact of the pandemic on physicians’ choices and the trend toward hospital medicine is an interested question, Dr. Sharpe said. The current study showed only trends through 2017.

“To be honest, I think it is difficult to predict,” he said. “Hospitalists shouldered much of the burden of COVID care nationally and burnout rates are high. One could imagine the extra work (as well as concern for personal safety) could lead to fewer providers choosing hospital medicine.

“At the same time, the pandemic has driven many of us to reflect on life and our values and what is important and, through that lens, providers might choose hospital medicine as a more sustainable, do-able, rewarding, and enjoyable career choice,” Dr. Sharpe emphasized.

“Additional research could explore the drivers of this clear trend toward hospital medicine. Determining what is motivating this trend could help hospitals and health systems ensure they have the right workforce for the future and, in particular, how to create outpatient positions that are attractive and rewarding,” he said.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers and Dr. Sharpe disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a new study, published in Annals of Internal Medicine, researchers from ABIM reviewed certification data from 67,902 general internists, accounting for 80% of all general internists certified in the United States from 1990 to 2017.

The researchers also used data from Medicare fee-for-service claims from 2008-2018 to measure and categorize practice setting types. The claims were from patients aged 65 years or older with at least 20 evaluation and management visits each year. Practice settings were categorized as hospitalist, outpatient, or mixed.

“ABIM is always working to understand the real-life experience of physicians, and this project grew out of that sort of analysis,” lead author Bradley M. Gray, PhD, a health services researcher at ABIM in Philadelphia, said in an interview. “We wanted to better understand practice setting, because that relates to the kinds of questions that we ask on our certifying exams. When we did this, we noticed a trend toward hospital medicine.”

Overall, the percentages of general internists in hospitalist practice and outpatient-only practice increased during the study period, from 25% to 40% and from 23% to 38%, respectively. By contrast, the percentage of general internists in a mixed-practice setting decreased from 52% to 23%, a 56% decline. Most of the physicians who left the mixed practice setting switched to outpatient-only practices.

Among the internists certified in 2017, 71% practiced as hospitalists, compared with 8% practicing as outpatient-only physicians. Most physicians remained in their original choice of practice setting. For physicians certified in 1999 and 2012, 86% and 85%, respectively, of those who chose hospitalist medicine remained in the hospital setting 5 years later, as did 95% of outpatient physicians, but only 57% of mixed-practice physicians.

The shift to outpatient practice among senior physicians offset the potential decline in outpatient primary care resulting from the increased choice of hospitalist medicine by new internists, the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the reliance on Medicare fee-for-service claims, the researchers noted.

“We were surprised by both the dramatic shift toward hospital medicine by new physicians and the shift to outpatient only (an extreme category) for more senior physicians,” Dr. Gray said in an interview.

The shift toward outpatient practice among older physicians may be driven by convenience, said Dr. Gray. “I suspect that it is more efficient to specialize in terms of practice setting. Only seeing patients in the outpatient setting means that you don’t have to travel to the hospital, which can be time consuming.

“Also, with fewer new physicians going into primary care, older physicians need to focus on outpatient visits. This could be problematic in the future as more senior physicians retire and are replaced by new physicians who focus on hospital care,” which could lead to more shortages in primary care physicians, he explained.

The trend toward hospital medicine as a career has been going on since before the pandemic, said Dr. Gray. “I don’t think the pandemic will ultimately impact this trend. That said, at least in the short run, there may have been a decreased demand for primary care, but that is just my speculation. As more data flow in we will be able to answer this question more directly.”

Next steps for research included digging deeper into the data to understand the nature of conditions facing hospitalists, Dr. Gray said.

Implications for primary care

“This study provides an updated snapshot of the popularity of hospital medicine,” said Bradley A. Sharpe, MD, of the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. “It is also important to conduct this study now as health systems think about the challenge of providing high-quality primary care with a rapidly decreasing number of internists choosing to practice outpatient medicine.” Dr. Sharpe was not involved in the study.

“The most surprising finding to me was not the increase in general internists focusing on hospital medicine, but the amount of the increase; it is remarkable that nearly three quarters of general internists are choosing to practice as hospitalists,” Dr. Sharpe noted.

“I think there are a number of key factors at play,” he said. “First, as hospital medicine as a field is now more than 25 years old, hospitals and health systems have evolved to create hospital medicine jobs that are interesting, engaging, rewarding (financially and otherwise), doable, and sustainable. Second, being an outpatient internist is incredibly challenging; multiple studies have shown that it is essentially impossible to complete the evidence-based preventive care for a panel of patients on top of everything else. We know burnout rates are often higher among primary care and family medicine providers. On top of that, the expansion of electronic health records and patient access has led to a massive increase in messages to providers; this has been shown to be associated with burnout.”

The potential impact of the pandemic on physicians’ choices and the trend toward hospital medicine is an interested question, Dr. Sharpe said. The current study showed only trends through 2017.

“To be honest, I think it is difficult to predict,” he said. “Hospitalists shouldered much of the burden of COVID care nationally and burnout rates are high. One could imagine the extra work (as well as concern for personal safety) could lead to fewer providers choosing hospital medicine.

“At the same time, the pandemic has driven many of us to reflect on life and our values and what is important and, through that lens, providers might choose hospital medicine as a more sustainable, do-able, rewarding, and enjoyable career choice,” Dr. Sharpe emphasized.

“Additional research could explore the drivers of this clear trend toward hospital medicine. Determining what is motivating this trend could help hospitals and health systems ensure they have the right workforce for the future and, in particular, how to create outpatient positions that are attractive and rewarding,” he said.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers and Dr. Sharpe disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a new study, published in Annals of Internal Medicine, researchers from ABIM reviewed certification data from 67,902 general internists, accounting for 80% of all general internists certified in the United States from 1990 to 2017.

The researchers also used data from Medicare fee-for-service claims from 2008-2018 to measure and categorize practice setting types. The claims were from patients aged 65 years or older with at least 20 evaluation and management visits each year. Practice settings were categorized as hospitalist, outpatient, or mixed.

“ABIM is always working to understand the real-life experience of physicians, and this project grew out of that sort of analysis,” lead author Bradley M. Gray, PhD, a health services researcher at ABIM in Philadelphia, said in an interview. “We wanted to better understand practice setting, because that relates to the kinds of questions that we ask on our certifying exams. When we did this, we noticed a trend toward hospital medicine.”

Overall, the percentages of general internists in hospitalist practice and outpatient-only practice increased during the study period, from 25% to 40% and from 23% to 38%, respectively. By contrast, the percentage of general internists in a mixed-practice setting decreased from 52% to 23%, a 56% decline. Most of the physicians who left the mixed practice setting switched to outpatient-only practices.

Among the internists certified in 2017, 71% practiced as hospitalists, compared with 8% practicing as outpatient-only physicians. Most physicians remained in their original choice of practice setting. For physicians certified in 1999 and 2012, 86% and 85%, respectively, of those who chose hospitalist medicine remained in the hospital setting 5 years later, as did 95% of outpatient physicians, but only 57% of mixed-practice physicians.

The shift to outpatient practice among senior physicians offset the potential decline in outpatient primary care resulting from the increased choice of hospitalist medicine by new internists, the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the reliance on Medicare fee-for-service claims, the researchers noted.

“We were surprised by both the dramatic shift toward hospital medicine by new physicians and the shift to outpatient only (an extreme category) for more senior physicians,” Dr. Gray said in an interview.

The shift toward outpatient practice among older physicians may be driven by convenience, said Dr. Gray. “I suspect that it is more efficient to specialize in terms of practice setting. Only seeing patients in the outpatient setting means that you don’t have to travel to the hospital, which can be time consuming.

“Also, with fewer new physicians going into primary care, older physicians need to focus on outpatient visits. This could be problematic in the future as more senior physicians retire and are replaced by new physicians who focus on hospital care,” which could lead to more shortages in primary care physicians, he explained.

The trend toward hospital medicine as a career has been going on since before the pandemic, said Dr. Gray. “I don’t think the pandemic will ultimately impact this trend. That said, at least in the short run, there may have been a decreased demand for primary care, but that is just my speculation. As more data flow in we will be able to answer this question more directly.”

Next steps for research included digging deeper into the data to understand the nature of conditions facing hospitalists, Dr. Gray said.

Implications for primary care

“This study provides an updated snapshot of the popularity of hospital medicine,” said Bradley A. Sharpe, MD, of the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. “It is also important to conduct this study now as health systems think about the challenge of providing high-quality primary care with a rapidly decreasing number of internists choosing to practice outpatient medicine.” Dr. Sharpe was not involved in the study.

“The most surprising finding to me was not the increase in general internists focusing on hospital medicine, but the amount of the increase; it is remarkable that nearly three quarters of general internists are choosing to practice as hospitalists,” Dr. Sharpe noted.

“I think there are a number of key factors at play,” he said. “First, as hospital medicine as a field is now more than 25 years old, hospitals and health systems have evolved to create hospital medicine jobs that are interesting, engaging, rewarding (financially and otherwise), doable, and sustainable. Second, being an outpatient internist is incredibly challenging; multiple studies have shown that it is essentially impossible to complete the evidence-based preventive care for a panel of patients on top of everything else. We know burnout rates are often higher among primary care and family medicine providers. On top of that, the expansion of electronic health records and patient access has led to a massive increase in messages to providers; this has been shown to be associated with burnout.”

The potential impact of the pandemic on physicians’ choices and the trend toward hospital medicine is an interested question, Dr. Sharpe said. The current study showed only trends through 2017.

“To be honest, I think it is difficult to predict,” he said. “Hospitalists shouldered much of the burden of COVID care nationally and burnout rates are high. One could imagine the extra work (as well as concern for personal safety) could lead to fewer providers choosing hospital medicine.

“At the same time, the pandemic has driven many of us to reflect on life and our values and what is important and, through that lens, providers might choose hospital medicine as a more sustainable, do-able, rewarding, and enjoyable career choice,” Dr. Sharpe emphasized.

“Additional research could explore the drivers of this clear trend toward hospital medicine. Determining what is motivating this trend could help hospitals and health systems ensure they have the right workforce for the future and, in particular, how to create outpatient positions that are attractive and rewarding,” he said.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers and Dr. Sharpe disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Where Does the Hospital Belong? Perspectives on Hospital at Home in the 21st Century

From Medically Home Group, Boston, MA.

Brick-and-mortar hospitals in the United States have historically been considered the dominant setting for providing care to patients. The coordination and delivery of care has previously been bound to physical hospitals largely because multidisciplinary services were only accessible in an individual location. While the fundamental make-up of these services remains unchanged, these services are now available in alternate settings. Some of these services include access to a patient care team, supplies, diagnostics, pharmacy, and advanced therapeutic interventions. Presently, the physical environment is becoming increasingly irrelevant as the core of what makes the traditional hospital—the professional staff, collaborative work processes, and the dynamics of the space—have all been translated into a modern digitally integrated environment. The elements necessary to providing safe, effective care in a physical hospital setting are now available in a patient’s home.

Impetus for the Model

As hospitals reconsider how and where they deliver patient care because of limited resources, the hospital-at-home model has gained significant momentum and interest. This model transforms a home into a hospital. The inpatient acute care episode is entirely substituted with an intensive at-home hospital admission enabled by technology, multidisciplinary teams, and ancillary services. Furthermore, patients requiring post-acute support can be transitioned to their next phase of care seamlessly. Given the nationwide nursing shortage, aging population, challenges uncovered by the COVID-19 pandemic, rising hospital costs, nurse/provider burnout related to challenging work environments, and capacity constraints, a shift toward the combination of virtual and in-home care is imperative. The hospital-at-home model has been associated with superior patient outcomes, including reduced risks of delirium, improved functional status, improved patient and family member satisfaction, reduced mortality, reduced readmissions, and significantly lower costs.1 COVID-19 alone has unmasked major facility-based deficiencies and limitations of our health care system. While the pandemic is not the impetus for the hospital-at-home model, the extended stress of this event has created a unique opportunity to reimagine and transform our health care delivery system so that it is less fragmented and more flexible.

Nursing in the Model

Nursing is central to the hospital-at-home model. Virtual nurses provide meticulous care plan oversight, assessment, and documentation across in-home service providers, to ensure holistic, safe, transparent, and continuous progression toward care plan milestones. The virtual nurse monitors patients using in-home technology that is set up at the time of admission. Connecting with patients to verify social and medical needs, the virtual nurse advocates for their patients and uses these technologies to care and deploy on-demand hands-on services to the patient. Service providers such as paramedics, infusion nurses, or home health nurses may be deployed to provide services in the patient’s home. By bringing in supplies, therapeutics, and interdisciplinary team members, the capabilities of a brick-and-mortar hospital are replicated in the home. All actions that occur wherever the patient is receiving care are overseen by professional nursing staff; in short, virtual nurses are the equivalent of bedside nurses in the brick-and-mortar health care facilities.

Potential Benefits

There are many benefits to the hospital-at-home model (Table). This health care model can be particularly helpful for patients who require frequent admission to acute care facilities, and is well suited for patients with a range of conditions, including those with COVID-19, pneumonia, cellulitis, or congestive heart failure. This care model helps eliminate some of the stressors for patients who have chronic illnesses or other conditions that require frequent hospital admissions. Patients can independently recover at home and can also be surrounded by their loved ones and pets while recovering. This care approach additionally eliminates the risk of hospital-acquired infections and injuries. The hospital-at-home model allows for increased mobility,2 as patients are familiar with their surroundings, resulting in reduced onset of delirium. Additionally, patients with improved mobility performance are less likely to experience negative health outcomes.3 There is less chance of sleep disruption as the patient is sleeping in their own bed—no unfamiliar roommate, no call bells or health care personnel frequently coming into the room. The in-home technology set up for remote patient monitoring is designed with the user in mind. Ease of use empowers the patient to collaborate with their care team on their own terms and center the priorities of themselves and their families.

Positive Outcomes

The hospital-at-home model is associated with positive outcomes. The authors of a systematic review identified 10 randomized controlled trials of hospital-at-home programs (with a total of 1372 patients), but were able to obtain data for only 5 of these trials (with a total of 844 patients).4 They found a 38% reduction in 6-month mortality for patients who received hospital care at home, as well as significantly higher patient satisfaction across a range of medical conditions, including patients with cellulitis and community-acquired pneumonia, as well as elderly patients with multiple medical conditions. The authors concluded that hospital care at home was less expensive than admission to an acute care hospital.4 Similarly, a meta-analysis done by Caplan et al5 that included 61 randomized controlled trials concluded that hospital at home is associated with reductions in mortality, readmission rates, and cost, and increases in patient and caregiver satisfaction. Levine et al2 found reduced costs and utilization with home hospitalization compared to in-hospital care, as well as improved patient mobility status.

The home is the ideal place to empower patients and caregivers to engage in self-management.2 Receiving hospital care at home eliminates the need for dealing with transportation arrangements, traffic, road tolls, and time/scheduling constraints, or finding care for a dependent family member, some of the many stressors that may be experienced by patients who require frequent trips to the hospital. For patients who may not be clinically suitable candidates for hospital at home, such as those requiring critical care intervention and support, the brick-and-mortar hospital is still the appropriate site of care. The hospital-at-home model helps prevent bed shortages in brick-and-mortar hospital settings by allowing hospital care at home for patients who meet preset criteria. These patients can be hospitalized in alternative locations such as their own homes or the residence of a friend. This helps increase health system capacity as well as resiliency.

In addition to expanding safe and appropriate treatment spaces, the hospital-at-home model helps increase access to care for patients during nonstandard hours, including weekends, holidays, or when the waiting time in the emergency room is painfully long. Furthermore, providing care in the home gives the clinical team valuable insight into the patient’s daily life and routine. Performing medication reconciliation with the medicine cabinet in sight and dietary education in a patient’s kitchen are powerful touch points.2 For example, a patient with congestive heart failure who must undergo diuresis is much more likely to meet their care goals when their home diet is aligned with the treatment goal. By being able to see exactly what is in a patient’s pantry and fridge, the care team can create a much more tailored approach to sodium intake and fluid management. Providers can create and execute true patient-centric care as they gain direct insight into the patient’s lifestyle, which is clearly valuable when creating care plans for complex chronic health issues.

Challenges to Implementation and Scaling

Although there are clear benefits to hospital at home, how to best implement and scale this model presents a challenge. In addition to educating patients and families about this model of care, health care systems must expand their hospital-at-home programs and provide education about this model to clinical staff and trainees, and insurers must create reimbursement paradigms. Patients meeting eligibility criteria to enroll in hospital at home is the easiest hurdle, as hospital-at-home programs function best when they enroll and service as many patients as possible, including underserved populations.

Upfront Costs and Cost Savings

While there are upfront costs to set up technology and coordinate services, hospital at home also provides significant total cost savings when compared to coordination associated with brick-and-mortar admission. Hospital care accounts for about one-third of total medical expenditures and is a leading cause of debt.2 Eliminating fixed hospital costs such as facility, overhead, and equipment costs through adoption of the hospital-at-home model can lead to a reduction in expenditures. It has been found that fewer laboratory and diagnostic tests are ordered for hospital-at-home patients when compared to similar patients in brick-and-mortar hospital settings, with comparable or better clinical patient outcomes.6 Furthermore, it is estimated that there are cost savings of 19% to 30% when compared to traditional inpatient care.6 Without legislative action, upon the end of the current COVID-19 public health emergency, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Service’s Acute Hospital Care at Home waiver will terminate. This could slow down scaling of the model.However, over the past 2 years there has been enough buy-in from major health systems and patients to continue the momentum of the model’s growth. When setting up a hospital-at-home program, it would be wise to consider a few factors: where in the hospital or health system entity structure the hospital-at-home program will reside, which existing resources can be leveraged within the hospital or health system, and what are the state or federal regulatory requirements for such a program. This type of program continues to fill gaps within the US health care system, meeting the needs of widely overlooked populations and increasing access to essential ancillary services.

Conclusion

It is time to consider our bias toward hospital-first options when managing the care needs of our patients. Health care providers have the option to advocate for holistic care, better experience, and better outcomes. Home-based options are safe, equitable, and patient-centric. Increased costs, consumerism, and technology have pushed us to think about alternative approaches to patient care delivery, and the pandemic created a unique opportunity to see just how far the health care system could stretch itself with capacity constraints, insufficient resources, and staff shortages. In light of new possibilities, it is time to reimagine and transform our health care delivery system so that it is unified, seamless, cohesive, and flexible.

Corresponding author: Payal Sharma, DNP, MSN, RN, FNP-BC, CBN; psharma@medicallyhome.com.

Disclosures: None reported.

1. Cai S, Laurel PA, Makineni R, Marks ML. Evaluation of a hospital-in-home program implemented among veterans. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(8):482-487.

2. Levine DM, Ouchi K, Blanchfield B, et al. Hospital-level care at home for acutely ill adults: a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(5):729-736. doi:10.1007/s11606-018-4307-z

3. Shuman V, Coyle PC, Perera S,et al. Association between improved mobility and distal health outcomes. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020;75(12):2412-2417. doi:10.1093/gerona/glaa086

4. Shepperd S, Doll H, Angus RM, et al. Avoiding hospital admission through provision of hospital care at home: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. CMAJ. 2009;180(2):175-182. doi:10.1503/cmaj.081491

5. Caplan GA, Sulaiman NS, Mangin DA, et al. A meta-analysis of “hospital in the home”. Med J Aust. 2012;197(9):512-519. doi:10.5694/mja12.10480

6. Hospital at Home. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Healthcare Solutions. Accessed May 20, 2022. https://www.johnshopkinssolutions.com/solution/hospital-at-home/

From Medically Home Group, Boston, MA.

Brick-and-mortar hospitals in the United States have historically been considered the dominant setting for providing care to patients. The coordination and delivery of care has previously been bound to physical hospitals largely because multidisciplinary services were only accessible in an individual location. While the fundamental make-up of these services remains unchanged, these services are now available in alternate settings. Some of these services include access to a patient care team, supplies, diagnostics, pharmacy, and advanced therapeutic interventions. Presently, the physical environment is becoming increasingly irrelevant as the core of what makes the traditional hospital—the professional staff, collaborative work processes, and the dynamics of the space—have all been translated into a modern digitally integrated environment. The elements necessary to providing safe, effective care in a physical hospital setting are now available in a patient’s home.

Impetus for the Model

As hospitals reconsider how and where they deliver patient care because of limited resources, the hospital-at-home model has gained significant momentum and interest. This model transforms a home into a hospital. The inpatient acute care episode is entirely substituted with an intensive at-home hospital admission enabled by technology, multidisciplinary teams, and ancillary services. Furthermore, patients requiring post-acute support can be transitioned to their next phase of care seamlessly. Given the nationwide nursing shortage, aging population, challenges uncovered by the COVID-19 pandemic, rising hospital costs, nurse/provider burnout related to challenging work environments, and capacity constraints, a shift toward the combination of virtual and in-home care is imperative. The hospital-at-home model has been associated with superior patient outcomes, including reduced risks of delirium, improved functional status, improved patient and family member satisfaction, reduced mortality, reduced readmissions, and significantly lower costs.1 COVID-19 alone has unmasked major facility-based deficiencies and limitations of our health care system. While the pandemic is not the impetus for the hospital-at-home model, the extended stress of this event has created a unique opportunity to reimagine and transform our health care delivery system so that it is less fragmented and more flexible.

Nursing in the Model

Nursing is central to the hospital-at-home model. Virtual nurses provide meticulous care plan oversight, assessment, and documentation across in-home service providers, to ensure holistic, safe, transparent, and continuous progression toward care plan milestones. The virtual nurse monitors patients using in-home technology that is set up at the time of admission. Connecting with patients to verify social and medical needs, the virtual nurse advocates for their patients and uses these technologies to care and deploy on-demand hands-on services to the patient. Service providers such as paramedics, infusion nurses, or home health nurses may be deployed to provide services in the patient’s home. By bringing in supplies, therapeutics, and interdisciplinary team members, the capabilities of a brick-and-mortar hospital are replicated in the home. All actions that occur wherever the patient is receiving care are overseen by professional nursing staff; in short, virtual nurses are the equivalent of bedside nurses in the brick-and-mortar health care facilities.

Potential Benefits

There are many benefits to the hospital-at-home model (Table). This health care model can be particularly helpful for patients who require frequent admission to acute care facilities, and is well suited for patients with a range of conditions, including those with COVID-19, pneumonia, cellulitis, or congestive heart failure. This care model helps eliminate some of the stressors for patients who have chronic illnesses or other conditions that require frequent hospital admissions. Patients can independently recover at home and can also be surrounded by their loved ones and pets while recovering. This care approach additionally eliminates the risk of hospital-acquired infections and injuries. The hospital-at-home model allows for increased mobility,2 as patients are familiar with their surroundings, resulting in reduced onset of delirium. Additionally, patients with improved mobility performance are less likely to experience negative health outcomes.3 There is less chance of sleep disruption as the patient is sleeping in their own bed—no unfamiliar roommate, no call bells or health care personnel frequently coming into the room. The in-home technology set up for remote patient monitoring is designed with the user in mind. Ease of use empowers the patient to collaborate with their care team on their own terms and center the priorities of themselves and their families.

Positive Outcomes

The hospital-at-home model is associated with positive outcomes. The authors of a systematic review identified 10 randomized controlled trials of hospital-at-home programs (with a total of 1372 patients), but were able to obtain data for only 5 of these trials (with a total of 844 patients).4 They found a 38% reduction in 6-month mortality for patients who received hospital care at home, as well as significantly higher patient satisfaction across a range of medical conditions, including patients with cellulitis and community-acquired pneumonia, as well as elderly patients with multiple medical conditions. The authors concluded that hospital care at home was less expensive than admission to an acute care hospital.4 Similarly, a meta-analysis done by Caplan et al5 that included 61 randomized controlled trials concluded that hospital at home is associated with reductions in mortality, readmission rates, and cost, and increases in patient and caregiver satisfaction. Levine et al2 found reduced costs and utilization with home hospitalization compared to in-hospital care, as well as improved patient mobility status.

The home is the ideal place to empower patients and caregivers to engage in self-management.2 Receiving hospital care at home eliminates the need for dealing with transportation arrangements, traffic, road tolls, and time/scheduling constraints, or finding care for a dependent family member, some of the many stressors that may be experienced by patients who require frequent trips to the hospital. For patients who may not be clinically suitable candidates for hospital at home, such as those requiring critical care intervention and support, the brick-and-mortar hospital is still the appropriate site of care. The hospital-at-home model helps prevent bed shortages in brick-and-mortar hospital settings by allowing hospital care at home for patients who meet preset criteria. These patients can be hospitalized in alternative locations such as their own homes or the residence of a friend. This helps increase health system capacity as well as resiliency.

In addition to expanding safe and appropriate treatment spaces, the hospital-at-home model helps increase access to care for patients during nonstandard hours, including weekends, holidays, or when the waiting time in the emergency room is painfully long. Furthermore, providing care in the home gives the clinical team valuable insight into the patient’s daily life and routine. Performing medication reconciliation with the medicine cabinet in sight and dietary education in a patient’s kitchen are powerful touch points.2 For example, a patient with congestive heart failure who must undergo diuresis is much more likely to meet their care goals when their home diet is aligned with the treatment goal. By being able to see exactly what is in a patient’s pantry and fridge, the care team can create a much more tailored approach to sodium intake and fluid management. Providers can create and execute true patient-centric care as they gain direct insight into the patient’s lifestyle, which is clearly valuable when creating care plans for complex chronic health issues.

Challenges to Implementation and Scaling

Although there are clear benefits to hospital at home, how to best implement and scale this model presents a challenge. In addition to educating patients and families about this model of care, health care systems must expand their hospital-at-home programs and provide education about this model to clinical staff and trainees, and insurers must create reimbursement paradigms. Patients meeting eligibility criteria to enroll in hospital at home is the easiest hurdle, as hospital-at-home programs function best when they enroll and service as many patients as possible, including underserved populations.

Upfront Costs and Cost Savings

While there are upfront costs to set up technology and coordinate services, hospital at home also provides significant total cost savings when compared to coordination associated with brick-and-mortar admission. Hospital care accounts for about one-third of total medical expenditures and is a leading cause of debt.2 Eliminating fixed hospital costs such as facility, overhead, and equipment costs through adoption of the hospital-at-home model can lead to a reduction in expenditures. It has been found that fewer laboratory and diagnostic tests are ordered for hospital-at-home patients when compared to similar patients in brick-and-mortar hospital settings, with comparable or better clinical patient outcomes.6 Furthermore, it is estimated that there are cost savings of 19% to 30% when compared to traditional inpatient care.6 Without legislative action, upon the end of the current COVID-19 public health emergency, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Service’s Acute Hospital Care at Home waiver will terminate. This could slow down scaling of the model.However, over the past 2 years there has been enough buy-in from major health systems and patients to continue the momentum of the model’s growth. When setting up a hospital-at-home program, it would be wise to consider a few factors: where in the hospital or health system entity structure the hospital-at-home program will reside, which existing resources can be leveraged within the hospital or health system, and what are the state or federal regulatory requirements for such a program. This type of program continues to fill gaps within the US health care system, meeting the needs of widely overlooked populations and increasing access to essential ancillary services.

Conclusion

It is time to consider our bias toward hospital-first options when managing the care needs of our patients. Health care providers have the option to advocate for holistic care, better experience, and better outcomes. Home-based options are safe, equitable, and patient-centric. Increased costs, consumerism, and technology have pushed us to think about alternative approaches to patient care delivery, and the pandemic created a unique opportunity to see just how far the health care system could stretch itself with capacity constraints, insufficient resources, and staff shortages. In light of new possibilities, it is time to reimagine and transform our health care delivery system so that it is unified, seamless, cohesive, and flexible.

Corresponding author: Payal Sharma, DNP, MSN, RN, FNP-BC, CBN; psharma@medicallyhome.com.

Disclosures: None reported.

From Medically Home Group, Boston, MA.

Brick-and-mortar hospitals in the United States have historically been considered the dominant setting for providing care to patients. The coordination and delivery of care has previously been bound to physical hospitals largely because multidisciplinary services were only accessible in an individual location. While the fundamental make-up of these services remains unchanged, these services are now available in alternate settings. Some of these services include access to a patient care team, supplies, diagnostics, pharmacy, and advanced therapeutic interventions. Presently, the physical environment is becoming increasingly irrelevant as the core of what makes the traditional hospital—the professional staff, collaborative work processes, and the dynamics of the space—have all been translated into a modern digitally integrated environment. The elements necessary to providing safe, effective care in a physical hospital setting are now available in a patient’s home.

Impetus for the Model

As hospitals reconsider how and where they deliver patient care because of limited resources, the hospital-at-home model has gained significant momentum and interest. This model transforms a home into a hospital. The inpatient acute care episode is entirely substituted with an intensive at-home hospital admission enabled by technology, multidisciplinary teams, and ancillary services. Furthermore, patients requiring post-acute support can be transitioned to their next phase of care seamlessly. Given the nationwide nursing shortage, aging population, challenges uncovered by the COVID-19 pandemic, rising hospital costs, nurse/provider burnout related to challenging work environments, and capacity constraints, a shift toward the combination of virtual and in-home care is imperative. The hospital-at-home model has been associated with superior patient outcomes, including reduced risks of delirium, improved functional status, improved patient and family member satisfaction, reduced mortality, reduced readmissions, and significantly lower costs.1 COVID-19 alone has unmasked major facility-based deficiencies and limitations of our health care system. While the pandemic is not the impetus for the hospital-at-home model, the extended stress of this event has created a unique opportunity to reimagine and transform our health care delivery system so that it is less fragmented and more flexible.

Nursing in the Model

Nursing is central to the hospital-at-home model. Virtual nurses provide meticulous care plan oversight, assessment, and documentation across in-home service providers, to ensure holistic, safe, transparent, and continuous progression toward care plan milestones. The virtual nurse monitors patients using in-home technology that is set up at the time of admission. Connecting with patients to verify social and medical needs, the virtual nurse advocates for their patients and uses these technologies to care and deploy on-demand hands-on services to the patient. Service providers such as paramedics, infusion nurses, or home health nurses may be deployed to provide services in the patient’s home. By bringing in supplies, therapeutics, and interdisciplinary team members, the capabilities of a brick-and-mortar hospital are replicated in the home. All actions that occur wherever the patient is receiving care are overseen by professional nursing staff; in short, virtual nurses are the equivalent of bedside nurses in the brick-and-mortar health care facilities.

Potential Benefits

There are many benefits to the hospital-at-home model (Table). This health care model can be particularly helpful for patients who require frequent admission to acute care facilities, and is well suited for patients with a range of conditions, including those with COVID-19, pneumonia, cellulitis, or congestive heart failure. This care model helps eliminate some of the stressors for patients who have chronic illnesses or other conditions that require frequent hospital admissions. Patients can independently recover at home and can also be surrounded by their loved ones and pets while recovering. This care approach additionally eliminates the risk of hospital-acquired infections and injuries. The hospital-at-home model allows for increased mobility,2 as patients are familiar with their surroundings, resulting in reduced onset of delirium. Additionally, patients with improved mobility performance are less likely to experience negative health outcomes.3 There is less chance of sleep disruption as the patient is sleeping in their own bed—no unfamiliar roommate, no call bells or health care personnel frequently coming into the room. The in-home technology set up for remote patient monitoring is designed with the user in mind. Ease of use empowers the patient to collaborate with their care team on their own terms and center the priorities of themselves and their families.

Positive Outcomes

The hospital-at-home model is associated with positive outcomes. The authors of a systematic review identified 10 randomized controlled trials of hospital-at-home programs (with a total of 1372 patients), but were able to obtain data for only 5 of these trials (with a total of 844 patients).4 They found a 38% reduction in 6-month mortality for patients who received hospital care at home, as well as significantly higher patient satisfaction across a range of medical conditions, including patients with cellulitis and community-acquired pneumonia, as well as elderly patients with multiple medical conditions. The authors concluded that hospital care at home was less expensive than admission to an acute care hospital.4 Similarly, a meta-analysis done by Caplan et al5 that included 61 randomized controlled trials concluded that hospital at home is associated with reductions in mortality, readmission rates, and cost, and increases in patient and caregiver satisfaction. Levine et al2 found reduced costs and utilization with home hospitalization compared to in-hospital care, as well as improved patient mobility status.

The home is the ideal place to empower patients and caregivers to engage in self-management.2 Receiving hospital care at home eliminates the need for dealing with transportation arrangements, traffic, road tolls, and time/scheduling constraints, or finding care for a dependent family member, some of the many stressors that may be experienced by patients who require frequent trips to the hospital. For patients who may not be clinically suitable candidates for hospital at home, such as those requiring critical care intervention and support, the brick-and-mortar hospital is still the appropriate site of care. The hospital-at-home model helps prevent bed shortages in brick-and-mortar hospital settings by allowing hospital care at home for patients who meet preset criteria. These patients can be hospitalized in alternative locations such as their own homes or the residence of a friend. This helps increase health system capacity as well as resiliency.

In addition to expanding safe and appropriate treatment spaces, the hospital-at-home model helps increase access to care for patients during nonstandard hours, including weekends, holidays, or when the waiting time in the emergency room is painfully long. Furthermore, providing care in the home gives the clinical team valuable insight into the patient’s daily life and routine. Performing medication reconciliation with the medicine cabinet in sight and dietary education in a patient’s kitchen are powerful touch points.2 For example, a patient with congestive heart failure who must undergo diuresis is much more likely to meet their care goals when their home diet is aligned with the treatment goal. By being able to see exactly what is in a patient’s pantry and fridge, the care team can create a much more tailored approach to sodium intake and fluid management. Providers can create and execute true patient-centric care as they gain direct insight into the patient’s lifestyle, which is clearly valuable when creating care plans for complex chronic health issues.

Challenges to Implementation and Scaling

Although there are clear benefits to hospital at home, how to best implement and scale this model presents a challenge. In addition to educating patients and families about this model of care, health care systems must expand their hospital-at-home programs and provide education about this model to clinical staff and trainees, and insurers must create reimbursement paradigms. Patients meeting eligibility criteria to enroll in hospital at home is the easiest hurdle, as hospital-at-home programs function best when they enroll and service as many patients as possible, including underserved populations.

Upfront Costs and Cost Savings

While there are upfront costs to set up technology and coordinate services, hospital at home also provides significant total cost savings when compared to coordination associated with brick-and-mortar admission. Hospital care accounts for about one-third of total medical expenditures and is a leading cause of debt.2 Eliminating fixed hospital costs such as facility, overhead, and equipment costs through adoption of the hospital-at-home model can lead to a reduction in expenditures. It has been found that fewer laboratory and diagnostic tests are ordered for hospital-at-home patients when compared to similar patients in brick-and-mortar hospital settings, with comparable or better clinical patient outcomes.6 Furthermore, it is estimated that there are cost savings of 19% to 30% when compared to traditional inpatient care.6 Without legislative action, upon the end of the current COVID-19 public health emergency, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Service’s Acute Hospital Care at Home waiver will terminate. This could slow down scaling of the model.However, over the past 2 years there has been enough buy-in from major health systems and patients to continue the momentum of the model’s growth. When setting up a hospital-at-home program, it would be wise to consider a few factors: where in the hospital or health system entity structure the hospital-at-home program will reside, which existing resources can be leveraged within the hospital or health system, and what are the state or federal regulatory requirements for such a program. This type of program continues to fill gaps within the US health care system, meeting the needs of widely overlooked populations and increasing access to essential ancillary services.

Conclusion

It is time to consider our bias toward hospital-first options when managing the care needs of our patients. Health care providers have the option to advocate for holistic care, better experience, and better outcomes. Home-based options are safe, equitable, and patient-centric. Increased costs, consumerism, and technology have pushed us to think about alternative approaches to patient care delivery, and the pandemic created a unique opportunity to see just how far the health care system could stretch itself with capacity constraints, insufficient resources, and staff shortages. In light of new possibilities, it is time to reimagine and transform our health care delivery system so that it is unified, seamless, cohesive, and flexible.

Corresponding author: Payal Sharma, DNP, MSN, RN, FNP-BC, CBN; psharma@medicallyhome.com.

Disclosures: None reported.

1. Cai S, Laurel PA, Makineni R, Marks ML. Evaluation of a hospital-in-home program implemented among veterans. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(8):482-487.

2. Levine DM, Ouchi K, Blanchfield B, et al. Hospital-level care at home for acutely ill adults: a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(5):729-736. doi:10.1007/s11606-018-4307-z

3. Shuman V, Coyle PC, Perera S,et al. Association between improved mobility and distal health outcomes. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020;75(12):2412-2417. doi:10.1093/gerona/glaa086

4. Shepperd S, Doll H, Angus RM, et al. Avoiding hospital admission through provision of hospital care at home: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. CMAJ. 2009;180(2):175-182. doi:10.1503/cmaj.081491

5. Caplan GA, Sulaiman NS, Mangin DA, et al. A meta-analysis of “hospital in the home”. Med J Aust. 2012;197(9):512-519. doi:10.5694/mja12.10480

6. Hospital at Home. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Healthcare Solutions. Accessed May 20, 2022. https://www.johnshopkinssolutions.com/solution/hospital-at-home/

1. Cai S, Laurel PA, Makineni R, Marks ML. Evaluation of a hospital-in-home program implemented among veterans. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(8):482-487.

2. Levine DM, Ouchi K, Blanchfield B, et al. Hospital-level care at home for acutely ill adults: a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(5):729-736. doi:10.1007/s11606-018-4307-z

3. Shuman V, Coyle PC, Perera S,et al. Association between improved mobility and distal health outcomes. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020;75(12):2412-2417. doi:10.1093/gerona/glaa086

4. Shepperd S, Doll H, Angus RM, et al. Avoiding hospital admission through provision of hospital care at home: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. CMAJ. 2009;180(2):175-182. doi:10.1503/cmaj.081491

5. Caplan GA, Sulaiman NS, Mangin DA, et al. A meta-analysis of “hospital in the home”. Med J Aust. 2012;197(9):512-519. doi:10.5694/mja12.10480

6. Hospital at Home. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Healthcare Solutions. Accessed May 20, 2022. https://www.johnshopkinssolutions.com/solution/hospital-at-home/

The Intersection of Clinical Quality Improvement Research and Implementation Science

The Institute of Medicine brought much-needed attention to the need for process improvement in medicine with its seminal report To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System, which was issued in 1999, leading to the quality movement’s call to close health care performance gaps in Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century.1,2 Quality improvement science in medicine has evolved over the past 2 decades to include a broad spectrum of approaches, from agile improvement to continuous learning and improvement. Current efforts focus on Lean-based process improvement along with a reduction in variation in clinical practice to align practice with the principles of evidence-based medicine in a patient-centered approach.3 Further, the definition of quality improvement under the Affordable Care Act was framed as an equitable, timely, value-based, patient-centered approach to achieving population-level health goals.4 Thus, the science of quality improvement drives the core principles of care delivery improvement, and the rigorous evidence needed to expand innovation is embedded within the same framework.5,6 In clinical practice, quality improvement projects aim to define gaps and then specific steps are undertaken to improve the evidence-based practice of a specific process. The overarching goal is to enhance the efficacy of the practice by reducing waste within a particular domain. Thus, quality improvement and implementation research eventually unify how clinical practice is advanced concurrently to bridge identified gaps.7

System redesign through a patient-centered framework forms the core of an overarching strategy to support system-level processes. Both require a deep understanding of the fields of quality improvement science and implementation science.8 Furthermore, aligning clinical research needs, system aims, patients’ values, and clinical care give the new design a clear path forward. Patient-centered improvement includes the essential elements of system redesign around human factors, including communication, physical resources, and updated information during episodes of care. The patient-centered improvement design is juxtaposed with care planning and establishing continuum of care processes.9 It is essential to note that safety is rooted within the quality domain as a top priority in medicine.10 The best implementation methods and approaches are discussed and debated, and the improvement progress continues on multiple fronts.11 Patient safety systems are implemented simultaneously during the redesign phase. Moreover, identifying and testing the health care delivery methods in the era of competing strategic priorities to achieve the desirable clinical outcomes highlights the importance of implementation, while contemplating the methods of dissemination, scalability, and sustainability of the best evidence-based clinical practice.

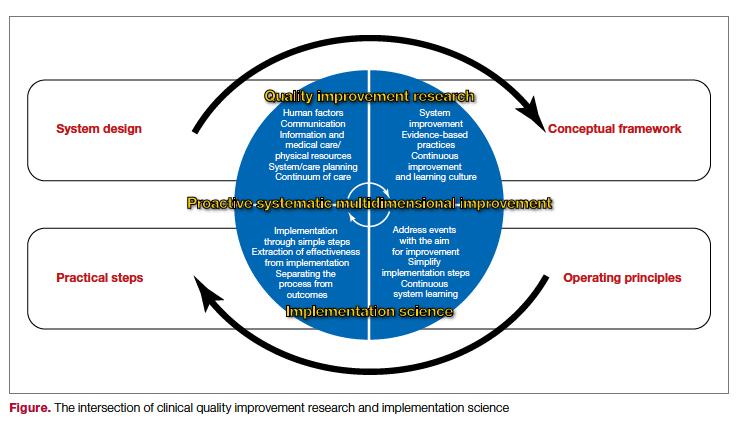

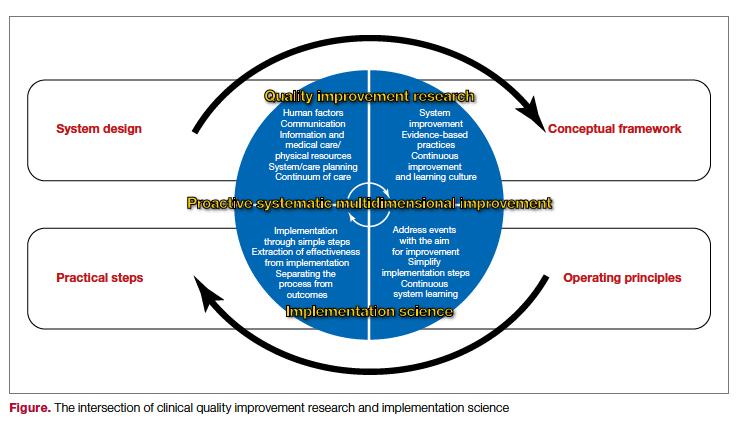

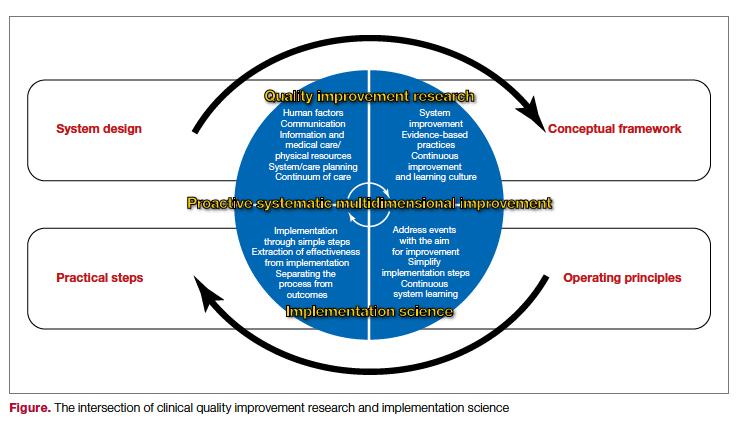

The cycle of quality improvement research completes the system implementation efforts. The conceptual framework of quality improvement includes multiple areas of care and transition, along with applying the best clinical practices in a culture that emphasizes continuous improvement and learning. At the same time, the operating principles should include continuous improvement in a simple and continuous system of learning as a core concept. Our proposed implementation approach involves taking simple and practical steps while separating the process from the outcomes measures, extracting effectiveness throughout the process. It is essential to keep in mind that building a proactive and systematic improvement environment requires a framework for safety, reliability, and effective care, as well as the alignment of the physical system, communication, and professional environment and culture (Figure).

In summary, system design for quality improvement research should incorporate the principles and conceptual framework that embody effective implementation strategies, with a focus on operational and practical steps. Continuous improvement will be reached through the multidimensional development of current health care system metrics and the incorporation of implementation science methods.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA; ebarkoudah@bwh.harvard.edu

Disclosures: None reported.

1. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2000.

2. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2001.

3. Berwick DM. The science of improvement. JAMA. 2008;299(10):1182-1184. doi:10.1001/jama.299.10.1182

4. Mazurenko O, Balio CP, Agarwal R, Carroll AE, Menachemi N. The effects of Medicaid expansion under the ACA: a systematic review. Health Affairs. 2018;37(6):944-950. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1491

5. Fan E, Needham DM. The science of quality improvement. JAMA. 2008;300(4):390-391. doi:10.1001/jama.300.4.390-b

6. Alexander JA, Hearld LR. The science of quality improvement implementation: developing capacity to make a difference. Med Care. 2011:S6-20. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e1709c

7. Rohweder C, Wangen M, Black M, et al. Understanding quality improvement collaboratives through an implementation science lens. Prev Med. 2019;129:105859. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105859

8. Bergeson SC, Dean JD. A systems approach to patient-centered care. JAMA. 2006;296(23):2848-2851. doi:10.1001/jama.296.23.2848

9. Leonard M, Graham S, Bonacum D. The human factor: the critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):i85-90. doi:10.1136/qhc.13.suppl_1.i85

10. Leape LL, Berwick DM, Bates DW. What practices will most improve safety? Evidence-based medicine meets patient safety. JAMA. 2002;288(4):501-507. doi:10.1001/jama.288.4.501

11. Auerbach AD, Landefeld CS, Shojania KG. The tension between needing to improve care and knowing how to do it. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(6):608-613. doi:10.1056/NEJMsb070738

The Institute of Medicine brought much-needed attention to the need for process improvement in medicine with its seminal report To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System, which was issued in 1999, leading to the quality movement’s call to close health care performance gaps in Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century.1,2 Quality improvement science in medicine has evolved over the past 2 decades to include a broad spectrum of approaches, from agile improvement to continuous learning and improvement. Current efforts focus on Lean-based process improvement along with a reduction in variation in clinical practice to align practice with the principles of evidence-based medicine in a patient-centered approach.3 Further, the definition of quality improvement under the Affordable Care Act was framed as an equitable, timely, value-based, patient-centered approach to achieving population-level health goals.4 Thus, the science of quality improvement drives the core principles of care delivery improvement, and the rigorous evidence needed to expand innovation is embedded within the same framework.5,6 In clinical practice, quality improvement projects aim to define gaps and then specific steps are undertaken to improve the evidence-based practice of a specific process. The overarching goal is to enhance the efficacy of the practice by reducing waste within a particular domain. Thus, quality improvement and implementation research eventually unify how clinical practice is advanced concurrently to bridge identified gaps.7

System redesign through a patient-centered framework forms the core of an overarching strategy to support system-level processes. Both require a deep understanding of the fields of quality improvement science and implementation science.8 Furthermore, aligning clinical research needs, system aims, patients’ values, and clinical care give the new design a clear path forward. Patient-centered improvement includes the essential elements of system redesign around human factors, including communication, physical resources, and updated information during episodes of care. The patient-centered improvement design is juxtaposed with care planning and establishing continuum of care processes.9 It is essential to note that safety is rooted within the quality domain as a top priority in medicine.10 The best implementation methods and approaches are discussed and debated, and the improvement progress continues on multiple fronts.11 Patient safety systems are implemented simultaneously during the redesign phase. Moreover, identifying and testing the health care delivery methods in the era of competing strategic priorities to achieve the desirable clinical outcomes highlights the importance of implementation, while contemplating the methods of dissemination, scalability, and sustainability of the best evidence-based clinical practice.

The cycle of quality improvement research completes the system implementation efforts. The conceptual framework of quality improvement includes multiple areas of care and transition, along with applying the best clinical practices in a culture that emphasizes continuous improvement and learning. At the same time, the operating principles should include continuous improvement in a simple and continuous system of learning as a core concept. Our proposed implementation approach involves taking simple and practical steps while separating the process from the outcomes measures, extracting effectiveness throughout the process. It is essential to keep in mind that building a proactive and systematic improvement environment requires a framework for safety, reliability, and effective care, as well as the alignment of the physical system, communication, and professional environment and culture (Figure).

In summary, system design for quality improvement research should incorporate the principles and conceptual framework that embody effective implementation strategies, with a focus on operational and practical steps. Continuous improvement will be reached through the multidimensional development of current health care system metrics and the incorporation of implementation science methods.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA; ebarkoudah@bwh.harvard.edu

Disclosures: None reported.

The Institute of Medicine brought much-needed attention to the need for process improvement in medicine with its seminal report To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System, which was issued in 1999, leading to the quality movement’s call to close health care performance gaps in Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century.1,2 Quality improvement science in medicine has evolved over the past 2 decades to include a broad spectrum of approaches, from agile improvement to continuous learning and improvement. Current efforts focus on Lean-based process improvement along with a reduction in variation in clinical practice to align practice with the principles of evidence-based medicine in a patient-centered approach.3 Further, the definition of quality improvement under the Affordable Care Act was framed as an equitable, timely, value-based, patient-centered approach to achieving population-level health goals.4 Thus, the science of quality improvement drives the core principles of care delivery improvement, and the rigorous evidence needed to expand innovation is embedded within the same framework.5,6 In clinical practice, quality improvement projects aim to define gaps and then specific steps are undertaken to improve the evidence-based practice of a specific process. The overarching goal is to enhance the efficacy of the practice by reducing waste within a particular domain. Thus, quality improvement and implementation research eventually unify how clinical practice is advanced concurrently to bridge identified gaps.7

System redesign through a patient-centered framework forms the core of an overarching strategy to support system-level processes. Both require a deep understanding of the fields of quality improvement science and implementation science.8 Furthermore, aligning clinical research needs, system aims, patients’ values, and clinical care give the new design a clear path forward. Patient-centered improvement includes the essential elements of system redesign around human factors, including communication, physical resources, and updated information during episodes of care. The patient-centered improvement design is juxtaposed with care planning and establishing continuum of care processes.9 It is essential to note that safety is rooted within the quality domain as a top priority in medicine.10 The best implementation methods and approaches are discussed and debated, and the improvement progress continues on multiple fronts.11 Patient safety systems are implemented simultaneously during the redesign phase. Moreover, identifying and testing the health care delivery methods in the era of competing strategic priorities to achieve the desirable clinical outcomes highlights the importance of implementation, while contemplating the methods of dissemination, scalability, and sustainability of the best evidence-based clinical practice.

The cycle of quality improvement research completes the system implementation efforts. The conceptual framework of quality improvement includes multiple areas of care and transition, along with applying the best clinical practices in a culture that emphasizes continuous improvement and learning. At the same time, the operating principles should include continuous improvement in a simple and continuous system of learning as a core concept. Our proposed implementation approach involves taking simple and practical steps while separating the process from the outcomes measures, extracting effectiveness throughout the process. It is essential to keep in mind that building a proactive and systematic improvement environment requires a framework for safety, reliability, and effective care, as well as the alignment of the physical system, communication, and professional environment and culture (Figure).

In summary, system design for quality improvement research should incorporate the principles and conceptual framework that embody effective implementation strategies, with a focus on operational and practical steps. Continuous improvement will be reached through the multidimensional development of current health care system metrics and the incorporation of implementation science methods.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA; ebarkoudah@bwh.harvard.edu

Disclosures: None reported.

1. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2000.

2. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2001.

3. Berwick DM. The science of improvement. JAMA. 2008;299(10):1182-1184. doi:10.1001/jama.299.10.1182

4. Mazurenko O, Balio CP, Agarwal R, Carroll AE, Menachemi N. The effects of Medicaid expansion under the ACA: a systematic review. Health Affairs. 2018;37(6):944-950. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1491

5. Fan E, Needham DM. The science of quality improvement. JAMA. 2008;300(4):390-391. doi:10.1001/jama.300.4.390-b

6. Alexander JA, Hearld LR. The science of quality improvement implementation: developing capacity to make a difference. Med Care. 2011:S6-20. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e1709c

7. Rohweder C, Wangen M, Black M, et al. Understanding quality improvement collaboratives through an implementation science lens. Prev Med. 2019;129:105859. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105859

8. Bergeson SC, Dean JD. A systems approach to patient-centered care. JAMA. 2006;296(23):2848-2851. doi:10.1001/jama.296.23.2848

9. Leonard M, Graham S, Bonacum D. The human factor: the critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):i85-90. doi:10.1136/qhc.13.suppl_1.i85

10. Leape LL, Berwick DM, Bates DW. What practices will most improve safety? Evidence-based medicine meets patient safety. JAMA. 2002;288(4):501-507. doi:10.1001/jama.288.4.501

11. Auerbach AD, Landefeld CS, Shojania KG. The tension between needing to improve care and knowing how to do it. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(6):608-613. doi:10.1056/NEJMsb070738

1. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2000.

2. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2001.

3. Berwick DM. The science of improvement. JAMA. 2008;299(10):1182-1184. doi:10.1001/jama.299.10.1182

4. Mazurenko O, Balio CP, Agarwal R, Carroll AE, Menachemi N. The effects of Medicaid expansion under the ACA: a systematic review. Health Affairs. 2018;37(6):944-950. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1491

5. Fan E, Needham DM. The science of quality improvement. JAMA. 2008;300(4):390-391. doi:10.1001/jama.300.4.390-b

6. Alexander JA, Hearld LR. The science of quality improvement implementation: developing capacity to make a difference. Med Care. 2011:S6-20. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e1709c

7. Rohweder C, Wangen M, Black M, et al. Understanding quality improvement collaboratives through an implementation science lens. Prev Med. 2019;129:105859. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105859

8. Bergeson SC, Dean JD. A systems approach to patient-centered care. JAMA. 2006;296(23):2848-2851. doi:10.1001/jama.296.23.2848

9. Leonard M, Graham S, Bonacum D. The human factor: the critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):i85-90. doi:10.1136/qhc.13.suppl_1.i85

10. Leape LL, Berwick DM, Bates DW. What practices will most improve safety? Evidence-based medicine meets patient safety. JAMA. 2002;288(4):501-507. doi:10.1001/jama.288.4.501

11. Auerbach AD, Landefeld CS, Shojania KG. The tension between needing to improve care and knowing how to do it. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(6):608-613. doi:10.1056/NEJMsb070738

A Quantification Method to Compare the Value of Surgery and Palliative Care in Patients With Complex Cardiac Disease: A Concept

From the Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Stanford University, Stanford, CA.

Abstract

Complex cardiac patients are often referred for surgery or palliative care based on the risk of perioperative mortality. This decision ignores factors such as quality of life or duration of life in either surgery or the palliative path. Here, we propose a model to numerically assess and compare the value of surgery vs palliation. This model includes quality and duration of life, as well as risk of perioperative mortality, and involves a patient’s preferences in the decision-making process.

For each pathway, surgery or palliative care, a value is calculated and compared to a normal life value (no disease symptoms and normal life expectancy). The formula is adjusted for the risk of operative mortality. The model produces a ratio of the value of surgery to the value of palliative care that signifies the superiority of one or another. This model calculation presents an objective estimated numerical value to compare the value of surgery and palliative care. It can be applied to every decision-making process before surgery. In general, if a procedure has the potential to significantly extend life in a patient who otherwise has a very short life expectancy with palliation only, performing high-risk surgery would be a reasonable option. A model that provides a numerical value for surgery vs palliative care and includes quality and duration of life in each pathway could be a useful tool for cardiac surgeons in decision making regarding high-risk surgery.

Keywords: high-risk surgery, palliative care, quality of life, life expectancy.

Patients with complex cardiovascular disease are occasionally considered inoperable due to the high risk of surgical mortality. When the risk of perioperative mortality (POM) is predicted to be too high, surgical intervention is denied, and patients are often referred to palliative care. The risk of POM in cardiac surgery is often calculated using large-scale databases, such as the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) records. The STS risk models, which are regularly updated, are based on large data sets and incorporate precise statistical methods for risk adjustment.1 In general, these calculators provide a percentage value that defines the magnitude of the risk of death, and then an arbitrary range is selected to categorize the procedure as low, medium, or high risk or inoperable status. The STS database does not set a cutoff point or range to define “operability.” Assigning inoperable status to a certain risk rate is problematic, with many ethical, legal, and moral implications, and for this reason, it has mostly remained undefined. In contrast, the low- and medium-risk ranges are easier to define. Another limitation encountered in the STS database is the lack of risk data for less common but very high-risk procedures, such as a triple valve replacement.